Nigerian Languages and Identity Crises1

Imelda Udoh & Ima Emmanuel

University of Uyo, Nigeria

Abstract Nigeria is home to over 500 languages (Lewis, 2009), accounting for 25% of languages spoken in Africa. Most have never been documented. 28 languages are listed in the UNESCO Atlas of Endangered Languages as endangered. In addition to these indigenous languages, there are three other foreign languages: English, French and Arabic, which have become part of the system over the years. English as the language of official communication, has a prominent place in the system. French was made Nigeria’s second official language since 1996 by General Sani Abacha’s regime, even though this has not been duly implemented. Arabic is connected to Islamic education, and it is used extensively in the northern parts of the country. Nigeria also has recognized three languages: Hausa, Yoruba and Igbo as ‘major’ languages, which attract a lot of government patronage, as opposed to the ‘minor’ languages, which have not attracted much government attention as they are very many. The Nigerian linguistic situation is therefore diverse, fragmented and chaotic. This linguistic situation has created a complex system which has engendered varied identities, leading to several crises in different areas. How can ‘Unity in Diversity’ be achieved in Nigeria? This paper explores the role of Nigerian languages in identity formation and the crises arising in different sectors of the Nigerian society. The identity crises explored here are: linguistic, political, ethnic and educational; and these are addressed within the framework of Social Identity Theory (SIT) proposed by Tajfel and Turner (1979, 2004). These crises marginalize, exclude and disempower certain groups and individuals in the society. A dual model of language programme is proposed for the Basic level of education to deal with these issues.

Keywords: Nigerian languages, identity crises, linguistic diversity, unity in diversity

1. Introduction

Nigeria’s official language is English. In addition to this, and perhaps the need to break off imperialistic ties, it has chosen three official regional languages—Hausa, spoken by about 20 million people in the North, Yoruba, spoken by about 19 million in the west, and Igbo, spoken by about 17 million people in a part of the south-east. These three languages are regarded as “major” languages. In addition to these three, there are about 500 other “languages” (some with very small numbers of speakers), referred to as “minor” languages (Crozier & Blench, 1992; Lewis,2009). Egbokhare et al. (2001) reduced this very large number of languages to 113 language clusters, using mutual intelligibility criterion in a preliminary report aimed at simplifying the current complex linguistic picture deriving from previous genetic classifications of these languages. Some of these languages have some degree of official status in their locality and are used as lingua franca, e.g. Efik, Ibibio, Fulani, etc. Within this network of indigenous languages, the Nigerian Pidgin is a national lingua franca. “Majority” languages in the Nigerian context, therefore, refer to Hausa, Yoruba and Igbo, while “Minority” languages refer to the languages that are spoken by the minority ethnic groups. This labels are officially recognised and they play significant roles in the different sectors in the country, especially the educational sector.

From the linguistic perspective, especially regarding the ecology, vitality and endangerment of the over 500 languages spoken in Nigeria, the languages have been grouped into five types: moribund/threatened languages, retreating languages, underdeveloped languages, developing languages and pidgin (Connell, 1994). Moribund and threatened languages are languages that are not being used, and as such are not transmitted to the younger generation. Such languages are threatened and endangered because they are on their way to extinction as a result of lack of use. Retreating languages are those that appear to be dying from a particular area, but still flourishing in another area. This is particularly obvious at inter-country boundaries. Underdeveloped languages are those languages without orthographies, written literature and meta-language. Developing languages are one step above the under-developed languages. They have fairly developed orthographies, and they are in the course of setting a literary tradition, with the instruments put in place for developing a metalanguage.

Nigeria has more than one-quarter of the languages spoken in Africa, and three of the four language phyla in Africa meet in Nigeria, namely: the Niger-Congo, Nilo-Saharan and Afro-Asiatic phyla. The uniqueness of these languages are not appreciated, and they are poorly researched. Much of the work on these languages have been done by foreigners, with funding from abroad. The existing works on these languages are mostly fragmented records made by non-native researchers with little knowledge of the languages and thus they fail to do justice to the linguistic data obtained. TheEthnologue(www.ethnologue.com), which provides some kind of linguistic database of 7,105 languages of the world, records 515 languages for Nigeria. Other works from which it apparently draws from have similar figures. Some of these include Crozier and Blench (1992), and more recently Blench (2012), which records 489 languages, with 200 of these being severely endangered and 20 moribund languages. In the absence of quality research from within, these works are used, even with some of the shortcomings in them. For instance, languages like Leggbó and Lokaa are no longer in Obubra LGA of Cross River State. Rather, Leggbó is in Abi, while Lokaa is in Yakurr. For a publication of 2012, the geopolitical information on most of the languages appears extremely outdated.

What this implies is that Nigerian languages are not adequately investigated and they are poorly researched. When compared with the volume and quality of research on the indigenous languages of Europe, America, Asia and Australia, it appears as though not much is being done here. Really, from the point of view of the researchers, funders and speakers, how much effort is being put into the work and use of Nigerian languages? Yet, Nigeria is very important to the global linguistic map, as its languages have very unique features and processes that have universal implications. They have remarkable linguistic heritage, yet they lack support and initiatives in concrete terms.

In addition to the indigenous languages, three foreign languages are spoken in Nigeria: English, French and Arabic. English is the official language, as mentioned earlier, French is the second official language, only in the Basic Level of Education (NPE, 2004). Arabic is the language of Islam. It has been used for religious, social, cultural and educational purposes, especially in northern Nigeria. These languages are used in the educational sector. Some are supposed to be used for instruction at certain levels of education, while some are supposed to be learnt as second languages.

Within the home, the formation of proper linguistic identity is not guaranteed. Children in all homes do not speak a mother-tongue, which should form the first social identification of the child’s primary social unit in the society. Mother-tongue here refers to the indigenous heritage language spoken in the home, which can be either the father’s or mother’s language, depending on the agreement in homes where both parents may not be from the same linguistic group. Such children lack an important tool of identity in the family. The unfortunate part is that sometimes, such children have parents who speak the same language, yet cannot transfer the same to their children. This lack of inter-generational transfer of the family language reduces the vitality of the language and deprives the children primary linguistic identity formations.

This paper presents some of the effects that the different languages Nigerian children have to deal with at different levels on their development of a sense of belonging to the nation-state.

2. Literature Review

Language is a very important part of man. It is an extremely important aspect of a community as well as an index of identity. It is an archive of the people and their way of life. There are many definitions of language. Bloch and Trager’s (1945, p. 5) definition as “a system of arbitrary vocal symbols by means of which a group cooperates” appears to be one of the most popular. Philosophically, Chomsky (1968, p. 41) describes language as “a species-specific possession, the human essence”, while Essien (1990) describes it as the “quintessence of humanity”.

Language is a very important tool in the process of achieving individual, group and national identification. Many scholars have identified it as the means for ensuring integration, continuity, stability and growth among different ethnic groups in the society (Fishman, 1979; Gordon, 1987; Bamgbose, 1991). Different social groups wish to see their linguistic identities reflected and recognized in the society they belong to.

The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Persons Belonging to National or Ethnic, Religious and Linguistic Minorities (1992), Resolution 47/135, cited in Crystal (1997, p. 371) states:

Article 1.1 States shall protect the existence and the national or ethnic, cultural, religious and linguistic identity of minorities within their respective territories, and shall encourage conditions for the promotion of that identity.

Article 2.1 Persons belonging to (minorities) have the right to enjoy their own culture, to profess and practise their own religion, and to use their own language, in private and in public, freely and without interference or any form of discrimination.

Article 4.3 States should take appropriate measures so that wherever possible, persons belonging to minorities have adequate opportunities to learn their mother-tongue or have instruction in their mother-tongue.

Article 4.4 States should, where appropriate, take measures in the field of education, in order to encourage knowledge of the history, traditions, language and culture of the minorities existing within their territory.

This Declaration recognizes the importance of language to a people. It can both divide and unite them, and so, it needs to be handled with utmost care.

3. National Identity and Unity in Diversity in Nigeria

Nigeria is a nation built from several ethnic groups with several languages. This multiple configuration of groups makes it difficult to cultivate a national identity, where national identity refers to the distinguishing characteristics of a nation, defined in terms of ethnicity, language, culture, etc. It involves a situation where “a feeling of belonging is cultivated in those who feel that they are not left out of the scheme of things” (Elugbe, 1990, p. 15).

Nigeria has a population estimate of about 150 million according to the 2006 census by the National Population Commission. Nigeria today has thirty-six States and the Federal Capital Territory (FCT). The political and linguistic map of Nigeria are shown below:This number of States has been a result of several creation exercises by different regimes in Nigeria’s political history. State creation in Nigeria began in 1967 under the “State Creation and Transitional Provision” Decree No. 14 by General Yakubu Gowon (Rtd). This was an attempt to solve the secession crisis of Biafra from Nigeria, and the creation of twelve States from the three Regions under this decree constituted the original States of the Federation of Nigeria (Udoma, 1994). A number of factors underlie the creation of States like the following:

1.realignment of boundaries of the colonial provinces as at 1960/61;

2. the wishes of the people and the communities based on common socio-cultural ties and institutions;

3. the historical association of the communities at the time of independence from colonial rule;

4. geographical contiguity, especially the need to avoid the “divide and rule” syndrome inherent in the present power structure and resource allocation;

5. the need to achieve a measure of relative balance in population and resource distribution.

None of these factors involves linguistic considerations, and this background has led to several adjustments of the geopolitical structure of the Nigerian State. We have so far had five State creation exercises in 1967, 1976, 1987, 1991 and 1996; as well as four Local Government Reforms in 1988, 1991, and 1996. Arising from these, we now have seven hundred and seventy-four L.G.As in Nigeria. The continued creation of States and L.G.As leads to the split of ethnic groups. Ethnic groups are “categories of people characterised by cultural criteria of normative behaviour, whose members are anchored in a particular part of the new state territory” (Otite, 2000, p. 12). An important index of ethnicity is language. With the split of such groups come break-ups of homogeneous linguistic groups which further compounds the linguistic complexity of the States. These groups overlap, sometimes forming a complicated network of languages.

Within the context of this ethnic multiplicity, the cliché “Unity in Diversity” has often been used to describe Nigeria as a country. Each State is made up of different ethnic groups, both major and minor. There are instances of neglect in terms of the development of some groups, and this creates problems, which have made the “Unity in Diversity” concept a mirage. Some groups, especially the minority ones feel aggrieved because they are neglected in the development of infrastructure and their languages. However, although these groups have separate characteristics which are peculiar to them, they share general features which, when combined, can qualify for a kind of “National Identity”.

National identity can, therefore, be seen from either a linguistic or an ethnic perspective, and within these groups, some elements of group identity include language, religion, long-standing institutions and traditional customs. Of all these, language is the most important index of nationalistic movement because it is an evident and widespread feature of community life.

4. Theoretical Considerations

We discuss the multifaceted crisis in Nigeria within the framework of Social Identity Theory (SIT), (Tajfel & Turner, 1979, 2004), with a focus on the linguistic, ethnic and political, as well as educational aspects of the situation. SIT refers to a person’s sense of self or who she is on the basis of group membership. Groups give a sense of social identity. An individual has multiple identities of self, drawn from affiliated groups. Two categories of groups prevail: the in-group, which is the group the individual identifies with; and the out-group, which others are stereotyped into. This creates a kind of “us” versus “them” mentality with peculiar identities. All these are processed through three social processes: social categorization, social identity and social comparison.

a.Social Categorization

The first of these processes is categorization. This is done because we need to understand and identify people in terms of family, profession, political affiliations, linguistic groups, etc. Such knowledge of groupings helps one to understand and define the behaviour of the members of the group. One can belong to many groups.

b Social Identification

Having identified with a group, one acts according to the ways of the group, and develops emotional significance to the group, such other things, like selfesteem become dependent on it.

c.Social Comparison

Having identified with a group, the features form a basis for comparison with others, and this sometimes leads to prejudice, discrimination, etc.

Social Identity Theory provides useful understanding of biases and judgements which give rise to discriminations among people in groups. This assessment by Islam 2014 is very apt and it has been used in our categorization of the different identities that the average Nigerian deals with through life, beginning from the family unit to the national level.

5. The Nigerian Identities

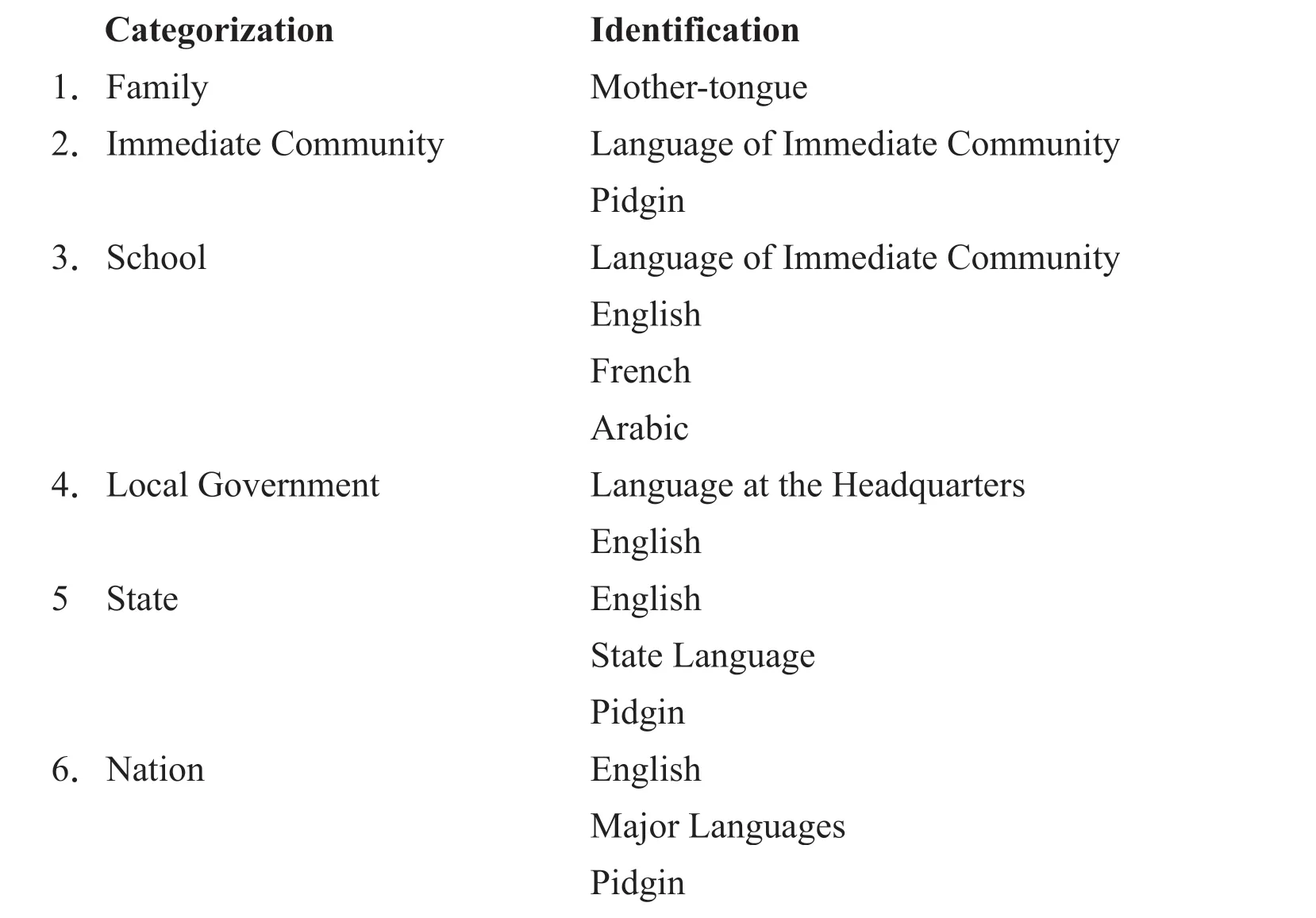

The Nigerian individual has multiple identities of self, drawn from the several groups she belongs to. From the smallest social unit, the family, to the national level, the individual processes several identities. A categorization of these identities are summarized below:

These groups help the individual to form and compare identities. Beginning from the smallest unit, the family, to the largest, the nation. The family is a very strategic group of identification in the hierarchy. The identification feature is the mothertongue, and it forms the basis of identification, the categorization and comparison with both other groups the individual may belong to, as well as compare with, following the SIT processing.

At age 5/6, when the child should begin the Basic Level of education, she should be grounded in both the mother-tongue and the Language of the Environment, which sometimes may be the same language. The child who skips these two to acquire the foreign language has skipped many “selves” in her development.

6. The Crises

In the midst of minor, major, foreign languages, ethnic groups in the system, there are identity crises. It is difficult to maintain a linguistic identity in such a chaotic situation. There are crises like the linguistic, ethnic, political and educational crises, which we discuss in this section.

6.1 Linguistic crises

Nigeria records over 500 languages. This linguistically fragmented picture is fraught with several problems. In some States of the Federation where almost every community speaks a different language from the next, one expects a lot of problems. Since this is a fact of history which we cannot avoid, we need to make the best use of the available resources. You have a linguistic identity when you consider yourself belonging to a group in which you speak the same language. But, we have a situation where a child speaks a mother-tongue at home, uses another language in the community (sometimes more than one), uses many more in the school (at different levels), etc. These languages are not presented to the child at the same time at an earlier age, which would have been learnt without any problem. They are presented at different developmental stages, and some are spoken and taught very poorly.

This leads to linguistic identity crises. At home, the child identifies with her mother-tongue. In school, she identifies with the Language of the Environment (LIC), which may not be that mother-tongue, and with which she is taught, up to Primary 3, according to theNational Policy on Education. From Primary 4, she begins to learn English, first as a subject and later it is used as a medium of instruction. French and Arabic are also introduced as school subjects at this stage.

6.2 Political and ethnic crises

The political growth of Nigeria has been a rather complex one. There have been several constitutions and changes in government at different times. The first attempt at democracy lasted for just 5 years. This was followed by an attempt of the Easterners to secede following the widespread massacre in Northern Nigeria of the Igbos, marked by a civil war which lasted until 1970. Within these series of turbulence and changes, there was a creation of States and LGAs by different governments at different times, all in the attempt to bring power and development as close to the grassroots as possible. With more creation of States came more awareness and further agitation for more States. With new creations, there was a need to create new identities.

In 1967, there was the creation of twelve States by General Yakubu Gowon out of the Eastern Region in an attempt to address the National Unity Question, one of which was the South-Eastern State. This set a tradition of State-creation in an attempt to cope with the peculiar heterogeneous nature of the country. In 1975, nineteen States were created by General Murtala Mohamed. States were from this point named after physical features like rivers. Thus the former, South Eastern State was renamed Cross River, after the Cross River. In 1987, General Ibrahim Babangida created two new States: Akwa Ibom (from former Cross River) and Katsina (from former Kaduna) States. Currently, there are thirty-six States, and Federal Capital Territory in Nigeria (see Map 1).

The Local Government system evolved from the traditional government. It appeared to be the best way to reach out to the grassroots (and vice versa) in our heterogeneous system, and this system had been adopted since the colonial era of Lord Fredrick Lugard. This system replaced the Indirect Rule since 1947 during the colonial era of Sir Arthur Richards. In 1950, there was a three-council system into the county (urban/municipality) councils, district councils and local councils. These were reduced to two in 1960. In 1975, this system was revived by the Murtala/Obasanjo regime. In the second republic, it led to the 1976 Reforms, which were later entrenched in the 1979 Constitution (Local Governments in Akwa Ibom State, 1996). In 1987, when Akwa Ibom State was carved out of the former Cross River, 7 LGAs were left in the State. In June 1989, when LGAs were again created in the country, the number increased to the present 18.

As mentioned earlier, the need to bring power and development to the grassroots is the overriding principle behind marking and readjusting geographical boundaries. Such boundaries, of course, do not always necessarily coincide with ethnic groups as different groups are sometimes of different sizes in population, and some groups may spread beyond a particular area for one reason or another. The creation of States and LGAs sometimes split ethnic groups and their languages. For instance, the Ibibio/Anaang group was separated from the Efik by the creation of Akwa Ibom State. These politically motivated adjustments create identity crises.

6.3 Educational crises

Nigeria has a uniform language policy for all language groups, in spite of linguistic diversity. This is stipulated in theNational Policy on Education(NPE) (2004).

The medium of instruction in the primary school is the Language of the Environment or Environment, which is supposed to be used for the first three years of education at this level. English is supposed to be taught during this period as a subject. So, the child begins this level of school at age 6, with her mother-tongue. This is for those who do not attend the pre-primary level. Although the medium of instruction in the pre-primary level is also supposed to be the mother-tongue or the Language of the Environment, this is not always the case, as the Schools at this level are dominantly owned by the private sector. Many of them try to justify their “International” status and as such do not abide by this aspect of the policy. They rather use English all the way and discourage the use of mother-tongues.

And yet, the curriculum for primary education includes the following language courses: Language of the Immediate Environment, English, French and Arabic. The Language of the immediate environment may not be the mother-tongue of all the students in the class.

7. A Proposal: Dual Model of Language Programme for the Basic Level

There are, as has been mentioned earlier, two categories of languages: the major three (Hausa, Yoruba and Igbo), and the minor (over 500) other languages. These languages are at different stages of development, but the government’s patronage of the major languages has made them more developed than the others.

The NPE (2004) Section 1, No. 10 stipulates:

10a. The government appreciates the importance of language as a means of promoting social interaction and national cohesion and preserving cultures. Thus, every child shall learn the language of the immediate environment. Furthermore, in the interest of national unity, it is expedient that every child shall be required to learn one of the three Nigerian languages: Hausa, Igbo and Yoruba.

b. For smooth interaction with our neighbours, it is desirable for every Nigerian to speak French. Accordingly, French shall be the second official language in Nigeria, and it shall be compulsory in Primary and Junior Secondary School but Non-Vocational elective at Senior Secondary School.

The Basic Level of education in Nigeria covers nine years of education, involving the Lower Primary Level, the Upper Primary level and the Junior Secondary School Level. Section 3, Nos 15 and 16 of the NPE stipulates that:

15. Basic education shall be of 9-year duration comprising 6 years of primary education and three years of Junior Secondary education. It shall be free and compulsory. It shall also include adult and non-formal education programmes at Primary and Junior Secondary education levels for the adults and out-of-school youths.

16. The specific goals of basic education shall be the same as the goals of the levels of education to which it applies (i.e. primary education, junior secondary and adult and nonformal education).

As important as the Basic level is, it has a lot of linguistic turmoil. The child begins school and receives instruction in the Language of the Environment, which may not be the mother-tongue she brought from home. After three years of receiving instruction in the Language of the Environment within this level, English is taken as a subject, and then the language of instruction switches to English. French and Arabic are also introduced at this level as subjects. A major challenge is the lack of teachers to teach these languages. They are poorly spoken, written and taught. This creates a problem.

A dual language programme, also called a “wo-way bilingual programme” is a form of bilingual education in which students are taught literacy and content in two languages. The current policy which uses the Language of the Environment is inadequate. The two languages should be used throughout the Basic Level, i.e. from Primary School (for 6 years) to Junior Secondary School (for 3 years). Nine years of the use of the two languages in instruction will help to create a balance in the children.

8. Conclusion and Recommendations

Nigeria, with so many linguistic groups, has the philosophy of living in unity and harmony as one individual, indissoluble, democratic and sovereign nation, founded on principles of freedom, equality and justice. It is important to achieve unity in such diversity as that which obtains in Nigeria. Indeed, multilingualism should promote social integration and this should be managed properly at different levels. It is not a hindrance to national unity, identity and integration. The multilingual nature of a society does not necessarily lead to divisiveness. It is rather the way the differences are handled that either leads to divisiveness or unification. Thus, if there are other factors like religious, political, moral, economic, cultural, social and traditional, etc. that bind people together, they can minimize language differences and therefore attain a common national identity and unification. To achieve this, some recommendations are made here.

1. A flexible dual model of language programme should be properly designed and entrenched in the NPE, especially for the Basic Level of the educational system. The Language of the Environment should not be terminated in the third year of Primary School as stipulated in the current NPE. Rather, it should be used alongside English throughout the Basic Level.

2. Beyond the formulation of the NPE, there should be a structure put in place to implement the policy properly.

3. The process of social identification should begin from home. Every Nigerian child should acquire a mother-tongue or father-tongue, as the case may be. That is a primary requirement for the family group and identity, and children need a tool of identity at that level of socialization.

4. Every child should step out of the home to deal with the Language of the Environment with an already acquired L1.

5. The intergenerational transfer of the mother-tongue should be backed up with a strategized advocacy, supported with some legislation.

6. Language is a very relevant tool in the process of achieving national identification, prestige, unity and development. Developing Nigerian indigenous languages will enable the government to “speak” to the people in languages they are competent in and this will promote national identity and national integration.

7. Nigeria should protect the existence of both the major and minor ethnic groups. They all have identities that are peculiar to them, and when these identities are promoted individually first, then each group, without misgivings can feel a better sense of belonging to a centre that is sensitive to its individual identity. Besides, every Nigerian has a right to use his own language both in private and in public without any form of discrimination. It is true that there are separate identities within the minor and major groups which are peculiar to them. But, because the groups share general features across them when combined, one can say that some kind of ‘National Identity’ in language, polity, customs, etc. can be achieved.

Note

1 Parts of this article appear in Udoh, 2017.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the Tertiary Education Trust Fund (TETFund) for a travel grant to attend the 19th Annual African Conference on “Identities” at the University of Texas, Austin, USA, in March 2019 where this paper was first presented.

Language and Semiotic Studies2020年3期

Language and Semiotic Studies2020年3期

- Language and Semiotic Studies的其它文章

- Do Unfamiliar Text Orientations Affect Transposed-Letter Word Recognition with Readers from Different Language Backgrounds?

- A Multimodal Critical Study of Selected Political Rally Campaign Discourse of 2011 Elections in Southwestern Nigeria

- Semiotic Resourcefulness in Crisis Risk Communication: The Case of COVID-19 Posters

- A Multimodal Discourse Analysis of Saudi Arabic Television Commercials

- The Temporality of Chinese from the Perspective of Semantic Relations

- A Study of Natural Elements in French Ecological Writer Jean Giono’s Works