Semiotic Resourcefulness in Crisis Risk Communication: The Case of COVID-19 Posters

Ningyang Chen

Soochow University, China

Abstract The unprecedented outbreak of COVID-19 presents a public health crisis on a global scale. Various measures have been taken to communicate crisis risks to the general public. These measures are meant to keep the public well informed, stay alert, and take precautionary measures to help curb the spread of the virus. The current study is part of an ongoing project aimed at exploring patterns of communication in the COVID-19 crisis discourse. Based on a collection of posters designed for public use during the outbreak, this paper analyses the richness of semiotic resources that combine to construct and convey the intended message of the posters. Drawing from scholarly insights into understanding the situatedness of meaning-making, the paper revisits some of the classical concerns about the relationship between text and image in semiotic artefacts and reveals the meaningmaking patterns in the semiotic designs of risk communication posters. The patterns are found to rest upon a host of textual and graphic features that contribute to the essential semiotic encoding of entity, condition, action, and sentiment. The findings are summarized by conceptualizing the assemblages of resources in the poster as a semiotic ensemble where the coordination and collaboration among semiotic resources can work to reduce potential ambiguities and amplify the communicative effect.

Keywords: semiotic resourcefulness, crisis risk communication, COVID-19, poster

1. Introduction

Perhaps no other incident in recent history has wreaked so much havoc than the coronavirus pandemic, which has claimed 682,415 lives worldwide by the end of July 2020 (Worldometer, 2020). The staggering death toll aside, the impact of the pandemic is acutely felt in all domains of life. Together with the disruptions to business, education, and industry, the global disaster has brought about long-term difficulties for all countries, with “the deepest recession since World War II” looming ahead (Richter, 2020). The United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) has defined the pandemic as “the defining global health crisis of our time” and “an unprecedented socio-economic crisis” as well (UNDP, 2020).

Since the announcement of COVID-19 as a global health crisis on 11 March 2020 by the World Health Organization (WHO), measures have been taken around the world to combat the spreading of the virus. While there arises an urgent need for medical resources and personnel, there is also an immediate need to communicate the risks to the general public. In response to this need, various channels have been improvised to help keep the public informed and actively involved in the battle. One major source of information is provided by the global internet. From journalistic reports to online counselling, a growing number of websites have taken up the social responsibility of fighting against the virus. Operators of these websites include commercial and non-profitable organizations, as well as government agencies. Several state governments have incorporated COVID-19 webpages on their official websites to publicize the updates and medical advice on controlling the virus. Among the official and non-official ways of communicating the risk information to the lay public, there emerges a convenient and widely available means of conveying the needed message—the use of purposefully designed posters.

The posters used in the COVID-19 pandemic fight feature various designs that mean to fulfil crude or refined functions. Some are for such general purposes as public alert and warning, others are for more specific purposes including entrance checklists, travel tips, and disinfection guidance. Most are provided in the form of printable files on websites for general access. For instance, during the pandemic, the Irish government website offers a collection of coronavirus posters for public use1where downloadable PDF-formatted posters are categorized under four headings: face coverings, hand hygiene, hand washing, and public information. Within each category, several usage scenarios are specified (e.g., face coverings on public transport, face coverings in shops). All posters are available in both English and Irish and are available in different print sizes (i.e., A2, A3, A4).

Posters as such are designed to convey risk-related information to the general public in a visible and accessible way. As a unique medium of communication in the public health crisis context, the COVID-19 poster makes a potentially interesting genre to explore. One point of interest to theoretically-minded researchers is that situations of contingency tend to influence a genre that may take on new properties less well understood than those of realizations of the genre in generic situations. In particular, it offers a look into the ways how meaning is made via a creative combination of resources to address an immediate situation, how communication is achieved between the professional world of knowledge and the amateur world of practice, and how the strategic use of the resources may contribute to the success of the communication. A second point of interest to practice-minded professionals is that when a stock of signs is not readily available for situated design or there arises an immediate need for the creation of new signs to communicate specific messages, being resourceful semiotically may be the way out of a resource “crisis”.

With these interests in mind, this paper presents the findings of one among a series of studies being undertaken to investigate risk communication in the COVID-19 crisis discourse. The current study examines a collection of posters designed for public use during the pandemic, focusing on the richness of semiotic resources and the way how they are mobilized and integrated to fulfil the communicative purpose of the posters. Before considering the findings of the study in detail, the paper will outline the scope and context of the study and the overall features of the posters under scrutiny. This is done by briefly reviewing previous discussions on the topic and empirical efforts to understand the issue at hand. The preliminary findings are then presented and discussed with illustrations from the collected poster samples. The paper concludes by considering the extended relevance of the inquiry and possible lines of further research.

2. Semiotic Resources in Poster Design

As a versatile artistic design, posters come in all types and forms. The components of a poster can be roughly sorted into text and image, with the former dealing with the presentation of linguistic signs and the latter concerning graphic elements. The proportion and distribution of text and image in a poster differ, yet the intended meaning of a poster can hardly be achieved without a cooperative combination of its text and image components. This section examines the generic poster under a semiotic lens to reveal how these components combine to generate “meaning” within and beyond the poster discourse and how such generated “meaning” is likely to be decoded by the audience, hence its communicative effect.

2.1 Poster as a communicative genre

As a commonplace printmaking today, the poster typically features a combination of textual and graphical content presented on a single page of varying sizes (Dominiczak, 2017). This versatile form of printed material can be used in a range of communicative situations for a variety of purposes. Some of the representative types are from government publications for political propaganda, product profiles for industrial advertising, infographic prints for conference presentations, and artistic designs for interior decoration. Judging by their primary functions and overall style, these types of posters can be roughly anchored on an informative-decorative as well as a formality continuum (Figure 1), with posters used for academic conference settings being typically more informative and formal than those used as wall decors.

Figure 1. A continuum of types of posters2

This diversity of functions may render an encompassing definition of posters invalid, yet as a powerful means of meaning expression, the poster can be approached as a genre of its kind. The famous German graphic designer Uwe Loesch offers a rather graphic description in a pseudo-verse entitled “A Poster Is a Poster and Not a Pipe”:

A poster has a message. Sometimes. A poster is a sheet of paper without a backside. A poster is a stamp. You can put it on the wall or on the window, on the ceiling or on the ground, upside down or wrong side up. There are young posters that look very old and old posters that never die. A good poster attacks you. A bad poster loves you. And there are “l’art-pour-l’art” posters that love themselves and want to be beautiful. These types of posters confuse the viewer, muddle up his eyes, and force him to look for something in the poster that is not inside. If you like, you can smoke it in your pipe. (Foster, 2006, p. 4)

Loesch’s comments on posters may speak more truly about the types that lean towards the artistic end on the informative-decorative continuum. However, the underlying message that a successful poster should create an effect on its viewer applies to posters of all types. Depending on the size and the effect, a poster can “attack”, “love”, or “self-love”, leaving its viewer in awe, in disgust, or in contempt. The effect a poster creates on the viewership comes from its communicative power. A successful poster communicates well with its viewers; one that fails to do so would lose its effectiveness.

2.2 Semiotic resources in a text-image compound

In fulfilling its functions to inform and communicate in an audience-friendly way, the poster often adopts tactfully designed individual components assembled within the layout of the page, intending to maximize the accessibility of the visual information displayed on the poster. The components come in forms of either text or image and each forms a semiotic system that interacts to shape the form and content of the poster. In this sense, the poster is within an array of designs which can be generally considered as a text-image compound in the sense that the constructed entity is composed of textual and graphical elements that can be distinguished and identified. Unpacking the relationship between these elements within the compound and the meaning-making mechanism thereof is at the centre of most semiotic studies on this topic.

In speaking of the relationship between text and image, Barthes identifies three types of messages out of the signification system embedded in a pasta advertisement. They are the linguistic message, the coded iconic message, and the noncoded iconic message (Barthes, 1977). He explains that the linguistic message, as expressed by the brand name printed on the package of the pasta has both denotational and connotational significance as it points to the name of the manufacturer as well as to the authenticity of the product (as the linguistic message is written in the native language of a country known for its pasta). The coded iconic message captures the connotations of the image, in the pasta example, culinary goodness and plentiful and peaceful life. The noncoded iconic message is what the photographic image speaks literally, a visual representation of the real-life objects that evokes an immediate construal of the entity. As the images are “floating chain” of signifieds, their meaning can only be pinned down by text: either in a system of anchorage, “the textdirectsthe reader through the signifieds of the image” and “remote-control[s] him towards a meaning chosen in advance” (ibid., pp. 39-40, emphasis original), or in a system of relay, where text and image form a complementary relationship, and “the unity of the message is realized at [the] level of the story, the anecdote, the diegesis” (ibid., p. 41). The primary role of the image, as Barthes concludes, is to naturalize and harmonize the otherwise ostensively artificial message of symbolism and connotation (Barthes, 1977).

Barthes’ interpretation dissects the image from the architect of signs and exposes it to a structured analysis, which tends to prioritize linguistic signs as the primary meaning-maker in the signification system. By either “anchoring” or “relaying”, the meaning of the image is generated by locating itself against or adapting itself to the decoded linguistic messages. One possible reason for the seeming inferiority of images is that unlike the linguistic message which conveys both denotational and connotational meaning, the imagery message conveys its meaning in separable ways. That is, while an image is meant to be connotative, it can be deprived of its denotational meaning if it declares distance from the depicted reality (a modernistic image, for instance, can be vaguely modelled after the reality, thus severing the denotative link).

Instead of insisting on a sharp division, some more recent scholars have argued for a relaxed boundary between the two with empirical evidence for a more integrated treatment of the text-image compound. When revisiting the “visual/verbal divide”, Bateman (2014) proposes a multimodality approach, borrowing linguistic terminology and empirical and experimental methods to describe and examine pictorial elements in a multimodal artefact. In particular, he argues for an inductive interpretation of the semiotic architect as the text-image relationship can only be determined in-situ rather thana prior.

Drawing upon evidence from Japanese calligraphy and typographical designs, Bartal (2013) charts out the changes in conceptualizing the relations between text and image as two semiotic fields during the modern to postmodern period shift. The study presents a convincing case for a radical reconceptualization of mutuality and interaction between the two systems. By showing how the creative design of Japanese calligraphy can turn the text into a visual image, it suggests a possible merging between the two separate fields.

With an interest to investigate the function of logo images in commercial posters, Scott (1993) examines the logotype as a visual/verbal signifier. The study reveals the potential to exploit resources from both sign systems for optimal formulation of the message. The double function of a logo that sits in between word and image, as Bartal observes, is to “iconizethe symbol” (2013, p. 107, emphasis original) on the one hand and to conventionalize the operation of the icon in the system on the other. This finding also helps obscure the division between text and image to the extent that a sign can be identified as lying in a middle state yet its value in fostering communication cannot be lightly dismissed.

The semiotic resources in poster design can be understood as a strategic selection and creation of text and image components that are brought together to make meaning in the specific communicative genre. As the communicative purpose of the poster varies, the features of its components are contingent on the situation where the communication occurs and the way how it unfolds. In the situation of a crisis, there arises a more immediate and pressing need to convey risk information to the public. Therefore, in comparison to previous findings that are largely based on analyses of text-image compounds designed for situations of less urgency, the current study focuses on those compounds as situated in a specific crisis scenario. It thus expects to reveal undocumented features of the semiotic architect used for risk commutation.

3. Semiotic Resources in COVID-19 Posters

The analysis is based on a corpus of posters collected continuously within six months after the outbreak of the coronavirus. The posters were downloaded from a wide range of authoritative websites (e.g., websites run by government agencies, well-established organizations) which had clear descriptions for the intended purpose and the suggested use of the poster files. For each included sample, care was taken to check the source, designer, published date, and other information deemed necessary for documentation. Then all the samples were manually coded for theme (or general focus) of the poster by the author of the paper and another researcher well-trained in qualitative research methods. A pilot coding was conducted to provide the initial categories and to ensure an agreed understanding of the coding scheme among the coders. The manual coding was done independently by two coders with high inter-coder reliability (Kappa .85). Disagreement was discussed until a consensus was reached. The thematic analysis identified four themes of prominence, i.e., disease alert, disease detection, personal/public hygiene measures, and public awareness. Illustrated with representative samples, this section takes a close look at the frequently used semiotic resources within these categories of poster design and discusses their characteristics in relation to constructing the crisis discourse.

3.1 The virus

As the culprit of the crisis, the image of the killer virus is presented variously across the posters targeting disease alert and detection. All can be considered as graphical representations of the real coronavirus, with varying degrees of abstraction and different stylistic preferences. Some are more abstract than others (e.g., Figure 2-1, 2-2); some appear more solemn than light-hearted (e.g., compare Figures 2-3 and 2-4). Despite this extensive range of idiosyncrasies, the poster depictions of the COVID-19 virus share a few common characteristics that assist ready recognition.

Figure 2. Graphical representations of the COVID-19 virus

The graphical representation of a virus is by no means a novel attempt, as the concept of a virus, whether in its medical or non-medical sense, has been well established. Before the pandemic, viruses are sometimes iconized using similar stock images to those for bacteria, featuring bug-like creatures (e.g., worms placed in a petri dish or under a magnifying glass). Though both are members of the germ family, the two differ in obvious ways, the most significant of which is that while bacteria are living organisms, viruses are not. This biological divergence defies the use of shared icon images, which may confuse the lay public and promote misunderstanding. One possible explanation for the use of bug-like creatures to iconize the germ indiscriminately is one of convenience. That is, the icon is largely created to convey the message that germs are, like bugs, generally unpleasant, dangerous, and to be prevented against. The overgeneration about germs (and possibly also about bugs) is deeply problematic, as there are “good” germs (e.g., probiotics) and “bad” ones judged from a humancentric perspective. Because the signified is tiny and unobservable to the naked eye, there is a need to “magnify” the microbiological world. The task is not an easy one as the visible world differs drastically from the world of the microbes. Hence, to alert people to the health risks of germs, one readily available resource is that of the familiar natural surroundings. The choice of the bug as an imitation of the microbe is not entirely random as they share the connotative meaning that is widely recognized and accords with the communicative intent of the discourse.

In terms of semiotic resources, one of the less anticipated by-products of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic is the growing stock of virus icons, and more specifically, the virus icons. With newly designed images being added to the stock daily, and the saturation of virus-related information, one would tend to readily equate virus with the COVID-19. On the one hand, it helps debunk the misconception that viruses are like bacteria and can be described in similar terms. Yet, on the other hand, as the interest in painting iconic portraits of the virus continues, there might be a risk of overgeneralization and overextension in that the COVID-19 icon would be popularized to become a paradigmatic symbol of viruses and even health hazards in general.

Though it takes professional training to draw an accurate portrait of the virus, the image presented needs to be recognized by the amateur with the least effort. To come up with a proper image one needs to establish a sign relation between the signified (the virus) and the signifier (its graphical representation). One intuitive way to do this is to capture the most striking features of the virus, as in the case of drawing a real portrait. This practice goes in line with the way how the lay public comes to know and understand objects defined in the professional domain. Given its biological complexity and the tools required to explore such complexity, the virus would remain unknowable to the public without the intentional efforts to promote awareness and educate. Presenting the virus to the public is thus essentially an educational practice as the public is expected to obtain the basic knowledge of the pandemic by recognizing the image of the virus. One common way to reduce the difficulty in communicating complex professional knowledge is to focus on the tangible rather than the abstract, as the former goes closer to bodily experience and can be more easily perceived by those who lack experience of dealing with conceptual constructs. Therefore, while a medical expert would concern himself with exploring the biological structure of the virus, a layperson would probably ask, “What does it look like?” This difference in interest and focus makes drawing virus portraits different businesses in the two scenarios. In the latter, as one would expect, the created images are often more flexible and encoded than in the former, where a more realistic and analogical representation is favoured.

A close look at the coronavirus images in the poster samples reveals a shared pattern—a two-dimensional design consisting of circles and lines (as typically presented in Figure 2-1). This pattern involves a serious reduction of some details and a purposeful exaggeration of some others. While a transmission electron microscopic view of the virus reveals a “bump-covered spherical appearance” which characterizes the coronavirus family (Bowler, 2020), its graphical representation features a spiky sphere which, one may imagine, can be easily reproduced by sticking a handful of thumbtacks into a playdough ball (see Figure 2-3). By disproportionally enlarging the “bumps”, reducing their density, and idealizing their distribution on the surface of the sphere, the graphical representation establishes an iconic relation between the real virus and the artistic design based thereupon. This relation is a practically reasonable one in that any further abstraction by omitting the essential details may cause misrecognition or failure of recognition, yet more elaborate depictions may be less concise and convenient than desired.

3.2 The symptoms

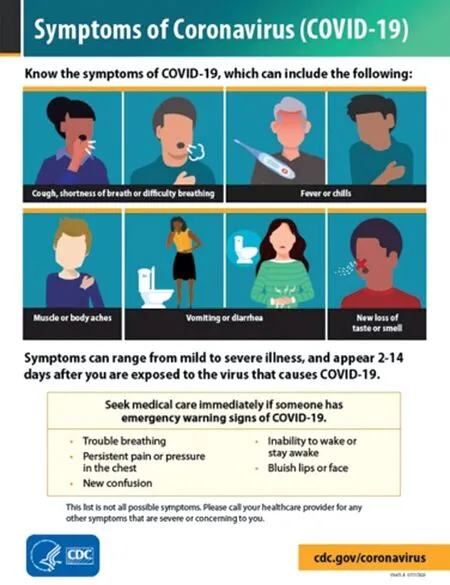

Another essential message to convey in the COVID-19 crisis is the diagnosing symptoms of the disease. As predicted, virus symptoms constitute the content of a substantial number of the collected posters, as showcased in a poster published by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)3below.

Figure 3. A CDC poster depicting symptoms of COVID-19

Unlike the virus, a symptom of the disease denotes a condition rather than an entity, thus its signification would involve the encoding of a more complex relationship than one involved in the mapping between an object and its semiotic counterpart. By accurate definition, though, a symptom is only a physical feature indicative of a medical condition, thus only related to the condition indirectly via an indicative link. The nature of the indication can be traced back to ancient Greek. The idea of a symptom came from the age-old interest in predicting bodily malfunctions, which gave rise to a field calledsemeiology(or medical semiotics). Instead of dealing with linguistic and philosophical concerns, it focuses on the diagnosis of physical dysfunctions which are believed to base on bothetiology(past) andprognosis(future) and can thus beprognosticated(foretold) by experienced physicians (Staiano, 1979), as Hippocrates famously noted in hisBook of Prognostics, one the earliest writings about medicine:

It appears to me a most excellent thing for the physician to cultivate Prognosis; for by foreseeing and foretelling, in the presence of the sick, the present, the past, and the future and explaining the omissions which patients have been guilty of, he will be the more readily believed to be acquainted with the circumstances of the sick; so that men will have confidence to entrust themselves to such a physician. (Hippocrates, 2006 [400 BCE])

Though equipped with much advanced diagnostic measures, physicians today continue to perform prognostics in “foreseeing and foretelling” the patient’s health condition. Such is the typical clinical scenario where the detection of symptoms take place. Detection can also happen in a nonclinical setting, though, especially at an early stage of the symptom development, when the person feeling sick needs to seek evidence to convince himself of the sickness and thus the necessity for folk or medical treatment. In a public health crisis, however, even the symptoms of commonplace illnesses (e.g., the common cold) are made more alarming and worrying than usual, as the coronavirus disease starts with some of the most common symptoms of illness (e.g., fatigue, headache, muscle aches, fever) and there are even infected cases showing no obvious symptoms. This weakness or lack of symptomatic evidence mystifies the disease to some extent, rendering it malleable to uninformed interpretations or guesses, especially among those who are overconcerned about the situation.

Therefore, the primary purpose of this category of posters is to alert the general public to the possible signs of the disease, which may lead to severe consequences if left untreated. On the other hand, by sending a properly hedged message based on science and empirical findings, the poster can help demystify the disease and prevent the spreading of paranoia. In general, the poster intends to make the public concerned, yet not overconcerned about the situation, and more importantly, seek medical help when in doubt about whether a symptom is real or not.

Most frequently, the symptoms are depicted in the posters using cartoon human figures as a representation of any individual. Such a generic reference is achieved by obliterating the individuality of the person presented. One detail to note is that in a fair proportion of symptom-themed posters (45.8%), the human figures are represented with minimal details of facial organs (e.g., eyes, nose, mouth), as found in Figures 3 and 4, where all the human figures are drawn in outline with no eyes on the face. The nose and mouth are included only in images where they are part of the organs affected by the symptom (e.g., loss of taste or smell affects the sensory organs of tongue and nose, hence the mouth and nose are included). This minimalizing act removes the persona from the person and as such reducing the representational relevance of the image as it is—the signified is not the person but the condition the person is suffering from.

The key to graphically encoding the complex relationship between the human subject and the indicative features it carries lies in foregrounding the latter against the background of the former. That is, the designer needs to reduce the details of the human subject to the degree that it refers to a genericidearather than the realizations of it, in this case, an individual is liable to the condition rather than one that resembles the figure in the image. This would also help reduce the decoding pressure on the viewers as they may focus their attention on how the signs of illness look like without being distracted by the possible suspicion that a specific group of people is more subject to the condition than others. In this sense, the signification of a condition tends to be semiotically more demanding than that of an entity as it involves the reinforcement of a (presumably weaker) sign relation at the reduction of the (presumably stronger) other.

3.3 The actions

One significant individual participation in the fight against the COVID-19 public health crisis is through conducting certain behaviours that are considered preventive against infection of the virus. At both the individual and the public level, the recommended sets of behaviours are demonstrated in over a third of the poster samples (36.2%). These posters can be further sorted into those focusing on one specific behaviour and those demonstrating a group of related behaviours. The following posters offered by the Regional Office for West and Central Africa4are three cases for specifying personal hygiene measures.

Figure 4. Poster samples of personal hygiene measures

How can hygiene measures be depicted in a poster? Specifically, this question concerns how semiotically a recommended action can be communicated to the public using a set of signs within a limited space. Dissimilar to the semiotic expression of an entity (the virus) and of a condition (symptoms), the description of a protective measure deals with what can essentially be thought of as an action. Compared with the relatively “static” signifieds (a virus or a symptom is not typically considered as “dynamic”), this group of signifieds is based on situations that typically involve a process of doing something (e.g., wear a face covering), hence an action. This difference is somewhat evident in the definition of the word “measure”, which denotes an action towards achieving a certain goal. In the crisis discourse, taking precautionary and preventative measures is essential to preparedness and response endeavours on the national and international levels; for individuals, taking proper hygiene measures is a small yet crucial contribution towards the shared goal of combating the disease.

The signification of the action is further restricted to a textual mode of expression, as compared to that of a video format that would allow the idea of an action to be conveyed in a synchronic, analogical manner. In a static print, however, it is not as easy to achieve an iconic representation since the iconicity of action can only be indirectly shown rather than expressed. Nevertheless, designers have come up with measures to cope with the absence of synchronicity mainly by depicting the process with a “highlight”. Instead of including the entire narrative context of the action, they choose only to include that part of the narration where the climax is reached. In the case of taking precautionary measures, it is the part where the risk of danger is at its highest. For example, one of the most frequently recommended measures in the posters is to cover one’s mouth and nose while sneezing or coughing (see Figure 4-1). This is to prevent the germs from being propelled into the air and, in the case of an infected individual, to prevent the spreading of the virus. The idea may seem simple, yet getting it across in a semiotically wise way can be difficult. The narrative context of this hypothetical action is one that in a real-world setting involves multiple factors: the overall setting, the person or the action-taker, the cause of the cough or sneeze, the person’s reaction to the cough or sneeze, the consequence of the person’s reaction. This series of episodes is too voluminous to be included all in a poster narration of the “covering your cough” incident. Hence, the designer leaves out the parts that are deemed not immediately relevant to the moment of danger. The only one being focused on is the instant moment after the person coughs or sneezes. By reducing the account of the incident to its climax, the design achieves the representational efficiency required in a poster genre. The dynamic process is condensed to a static depiction, the full episodes of which can be recovered by relating to shared experiences of illness.

One detail to note that distinguishes Figure 4-1 from the other two poster samples: in both Figures 4-2 and 4-3, there is a big red cross mark imposed on the image. The message conveyed by the added cross mark is that these actions are to be discouraged. This intuitive interpretation can be reflected upon with specific reference to the pressure of encoding an action-denoting signified. In linguistic messages, negation can be expressed either grammatically or lexically, as in the case of making a negative imperative, one may say “Don’t touch your face, nose and eyes” as an alternative to the text in Figure 4-2 “Avoid touching your face, nose and eyes”. The image of a cross mark is widely used as a symbol for wrongness, as opposed to the symbols for correctness (e.g., the tick mark, the circle mark).5The act of imposing this symbol on a semiotic representation negates the validity or legitimacy of the signified in the sense that the represented action is disapproved and to be avoided.

3.4 The mindsets

The difficulty in representing the abstract and the dynamic aside, there is yet a greater challenge in expressing a less articulatable message—one that deals with human psyche. Though a less prominent category in the collected posters (18.9%) compared with the more practical, functional posters, these posters illustrate the needed collective actions towards awareness and solidarity (see Figures 5-1 and 5-2).

Figure 5. Poster samples of public awareness

The overall communicative purpose of this category of posters differs from the previously considered three categories in several aspects. First, the purpose is more of an educational one than an informative one. That is, viewers may not expect to obtain knowledge or information about the pandemic by reading the poster. Instead, they would be epistemologically enlightened or psychologically motivated after digesting the message conveyed by the poster. Then, the posters are meant to provide an incentive for long-term changes in attitude and mentality rather than an immediate response of action. Third, since the intended messages appeal to the pathos of the audience, the communicative effect of the posters depends more on the personal character and experience of the viewer than on mere literacy, hence more individualistic readings and responses would be anticipated.

Semiotically, this representational situation lands designers in a paradox. On the one hand, the signified is not visible or perceptible, hence seeking an iconic relationship between a real-world imitation and the signified would be futile. One the other, creations out of pure imagination, which is not anchored in any reality at all, would be unfathomable. There does not appear to be a ready fix to this thorny problem, yet the poster designers have experimented with some solutions that seem promising. In Figure 5-1, the intended message of the poster is “say no to discrimination”. Since the start of the coronavirus outbreak, discrimination has been heatedly discussed as a major social concern. ALancetarticle specifies the issue as follows:

Outbreaks create fear, and fear is a key ingredient for racism and xenophobia to thrive. The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has uncovered social and political fractures within communities, with racialised and discriminatory responses to fear, disproportionately affecting marginalised groups. (Devakumar et al., 2020, p. 1194)

Although the idea of “say no to discrimination” can be rhetorically articulated in words, as the article authors tactfully demonstrate above, the expression task can be doubly challenging in a poster. For one thing, as empty talks impress no one, appealing to the pathos of the audience cannot easily be achieved by adopting banal patterns of design. For instance, the use of a stock image for discrimination may not strike the viewers as powerful and convincing, hence a necessity for innovation. Moreover, as a poster is not supposed to “say” much in words, the designer needs to use them sparingly, only in cases when the essential message would otherwise be distorted.

What the designer does, in this case, is to select from the emoticon stock five of the widely used items of person. The possible source emojis6are presented below in Figure 6.

Figure 6. Possible source emojis for the graphical representations of people in the “Say no to discrimination” poster

The use of emoticon can be regarded as an innovative attempt in its own right for it bridges two different domains of sign usage—social media and public life. While the conventional usage of the emoticons happens in interpersonal communication in social media, its adapted use takes place in the communication between the authority and the public through the mediation of a publicly displayed poster. To express the idea of discrimination, or the discourage thereof, the designer applies a differentiating colour scheme to the individual emoji images. Specifically, the image of a girl (Figure 6-1) and a man (Figure 6-5) are adapted to white skin colour and blond hair, whereas those of a boy (Figure 6-2), an old man (Figure 6-3) and a woman (Figure 6-4) are modified to take on dark skin colour with corresponding changes to the colour of the hair (except the image of the old man that retains grey hair). This adaptation creates a sharp contrast between the two groups identified by their skin colour: the white and the coloured. This contrast hints at the idea of discrimination with the representations of groups the conflict between whom is documented as a stereotype in the social act of racism and discrimination.

Furthermore, the message is articulated in the text placed above the image “We are ALL in this together. Say NO to discrimination”. The design of the text reinforces the idea by using differentiating colours and varying font sizes for the words. The white-black colour scheme again creates a contrast that echoes the one that stands in the skin colour of the emoji figures. The capitalization of ALL and NO highlights the key points of the message: the pandemic is a crisis threatening people of every race and nationality; racial discrimination is not to be tolerated if we want to survive the crisis.

The other design conveys the message of solidarity in a more subtle manner (Figure 5-2). “Solidarity” is by itself a difficult concept, mainly referring to “agreement between and support for the members of a group”7(Cambridge Dictionary). In the crisis context, the agreement and support may come from different sources and involve various groups. Therefore, in comparison to the “say no to discrimination” message, which targets at eliminating certain acts and attitudes, the intended meaning in this “solidity” message is not as clearly defined. To accord with the broadness and vagueness of the concept, the semiotic resources adopted to carry the message are equally “broad” and “vague” in the sense that the connotational significance of the images is exploited to create an extensive space of meaning potentials.

The poster features the graphical representations of two cupped hands. The symmetrical display of this pair of symbols gives off the connotation of steadiness and harmony. The text displayed in between the symbols hand images is separated into three lines, presented in all capital letters with decreasing font sizes: SOLIDARITY / AMID / COVID-19 CRISIS. This unique design bears semiotic significance in more ways than one. First, the iconic link between font size and the prominence (power) of the printed word is constructed on such a general cognitive association that the larger suggests the more prominent or powerful. In this light, the most prominent and powerful among the three notions printed is “solidarity”, while the least prominent and powerful is the “COVID-19 crisis”. The unbalance thus created implies that we shall triumph over the crisis if we stay in solidarity. The impression that the diminutive COVID-19 CRISIS creates violates the overwhelmingly powerful image of the virus. Then, the medium-sized word “amid” encodes multiple iconic relations. Not being a content word by itself, the functional preposition is not meant to carry any substantial meaning except the indication of a relative location. Nonetheless, its unique position in the layout of the poster—horizontally placedamidthe images of cupped hands; verticallyamidthe block of text—doubly echoes the denotational meaning of the word.

4. Assemblages between Text and Image: A Semiotic Ensemble

The analysis of the frequently adopted semiotic resources in the sample discussed above reveals a few patterns of assemblage, which can be considered as a purposeful combination and/or an artistical orchestration of the resources. The poster genre in this sense can be conceptualized as “a semiotic ensemble8”, a term borrowed from the field of language learning, where it has been adopted to target the mixed, individualistic approaches in a range of learning and acquisition practices (Bezemer & Kress, 2016; Costa Waetzold & Melo-Pfeifer, 2020; Mavers, 2007, 2009). To what extent and what qualities these patterns reveal about the relationship between text and image in the poster as a semiotic ensemble is the focus of this section.

4.1 Coordination and collaboration

Reconsider the informative-decorative continuum. When it comes to the text-image relation, one would expect the more informative types of posters to rely more heavily on text, yet the more decorative types to rely more actively on image to achieve the communicative purpose intended in each type of design. In general, this seems to be true, as poster hung along the conference poster gallery is normally ‘wordier’ than one that is hung on the sitting-room wall.

Though the COVID-19 posters would be considered as more informative and decorative given the pivotal role information plays in risk communication to the public, the text does not seem to feature prominently in the poster samples. For a large proportion of the samples, the opposite seems to be the case: image generally takes more space and is displayed with more prominence (e.g., colour, size, detailedness). The reason for this seems to be twofold. First, the poster in a crisis scenario needs to communicate in a highly efficient way, hence the essential information only. While the primary function of the poster is to inform the public, the information one carries is limited in scope and detail to ensure the efficiency of communication. Although a more thorough explanation of some of the illustrated points of note may assist better understanding, trading brevity for comprehensiveness at the risk of boring the audience is a price too high for shrewd designers to consider. Second, the overall prominence of image components in the poster samples may be explained away by pointing to the aphorism, “Images speak louder than words”. Although the merits of the image in terms of its communicative and pedagogical value have been well recognized in educational settings (e.g., Eilam & Poyas, 2012; Hassett & Curwood, 2009), the effect of using image-based posters in a crisis setting awaits to be assessed.

If the image tends to take much of the limelight from the text, one may venture to ask: Can images stand alone? Much as they may have been enhanced and focalized, this seems rarely to be the case. The following two examples illustrate how image and text function in interaction with each other in poster design. In the first example, the image of the virus (Figure 2-3) which has been mentioned in Section 3.1 is restored to its larger poster context (Figure 7) where it makes part of the image components.

Figure 7. A restored poster sample based on the coronavirus image

Apart from the most eye-catching image of the virus, this poster also contains an image of the contour of the world map in outline which is painted in bright red colour. In between the two image components is a text block consisting of two lines of words in large font sizes. The upper line features the word “coronavirus” printed with a font thickness comparable to the line thickness of the virus image. The lower line features the word “COVID-19” in bold font. These words may seem to convey a minimal amount of information, they are nonetheless important components of the poster in that they work to structurally coordinate the denotational and the connotational meanings of the semiotic architect. The name of the virus spelled in words that are presented in emphatic forms confirms the iconic relation between the signified and the image and as such enhances its expressiveness. As Barthes argues for the system of relay, the text goes with the image to construct a semiotic narration that impresses the audience. The effect of this coordinate could be made evident if the poster is compared with an edited image with deleted text.

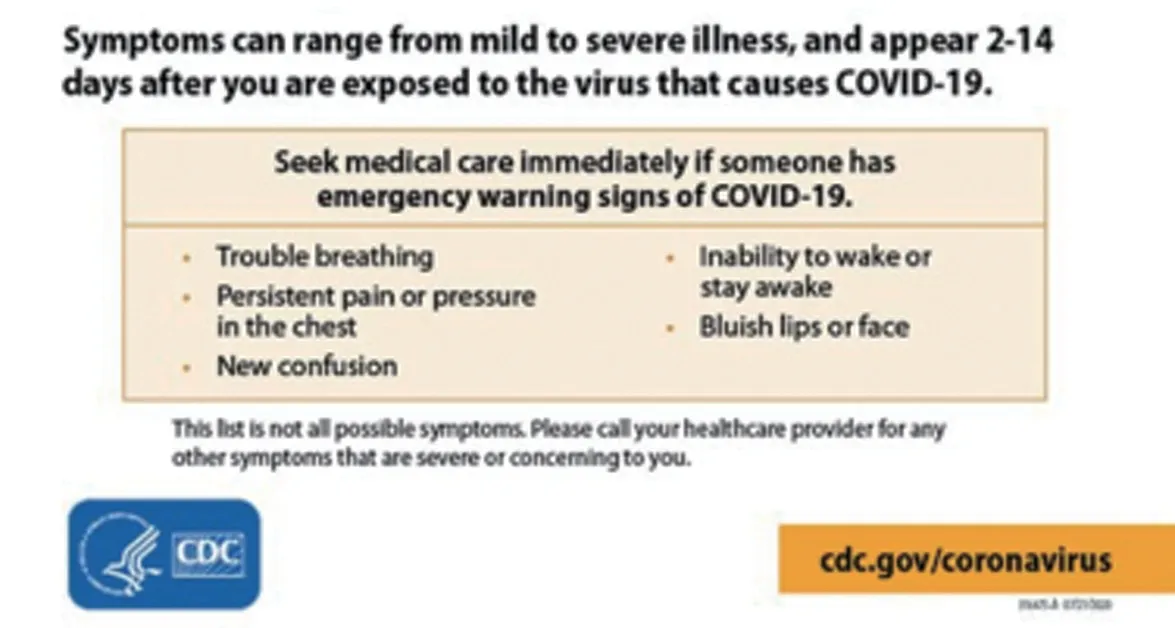

In addition to coordination, the text-image complex in a poster can also be subject to a more functional relationship—collaboration. One general limitation the graphical representations in the posters suffer from is the degree of detailedness. This limitation is clearer and more restricting in some situations than others. For instance, while the COVID-19 virus image would be readily recognized without its name spelled out in full, the symptoms of the virus may not be fully grasped in the absence of the explanatory text. Figure 3 displayed in Section 3.2 leaves almost half of the page for an explanation of the depicted symptoms (the major textual part redisplayed below as Figure 8). This textual component of the poster involves footnotes on the illustrated conditions, clarifying important details: severity and time of manifestation of the symptoms vary; the list is non-exhaustive; healthcare assistance is available. Also of note is a box where the names of some supplementary symptoms of the disease are displayed. These symptoms are found to be less malleable to pictorial expression (e.g., persistent pain or pressure in the chest, new confusion) than the more general, recognizable ones (e.g., fever or chills, muscle or body aches) illustrated with the cartoon human figures.

Figure 8. The major textual part of a CDC poster depicting symptoms of COVID-19

4.2 Unpacking a semiotic ensemble

Since the goal of the poster is to communicate messages to the public, how the messages are to be received would be the final test for the quality and effectiveness of the designs. In the absence of empirical evidence, a simulation of the process could be achieved by attempting a viewer perspective. Imagine a layperson who knows only the basics of medicine and is stranded in a heavily affected area in the COVID-19 pandemic. As a normal social being, this person learns about the crisis via exposure to mass media and interactions on social media. He knows what an average person in his social setting should know, yet with no particular interest in the topic, he does not make extra efforts to search for further information. Then what might be the response of the person when presented with the image component of a fabricated poster below?

Figure 9. A graphical representation of a coughing condition and possible interpretations

Unless read in a textual or graphical context, an isolated image as such is confusing. The human subject is depicted with an open mouth, with radiating lines indicative of airflow coming from the mouth. This visual information alone may not lead us to the desired decision that the image represents a cough as it could well be the case that human subject is uttering some sounds as in speaking. Suppose the person is not distracted by the possible alternative inferences and decides that the image represents a cough. However, without further explanation or contextualization, the image may still evoke vagueness given multiple possible interpretations. In communication scenarios, a cough can act as a cue for attention. In a medical context where it is more readily identified, the meaning of a cough is also refined. There are distinctions between coughs with different causes (e.g., heavy smoking, common cold, viral infection). Going from the features of getting a cough to confirmed infection by the virus is a long bow.

This hypothetical example points to the role of “context” in processing the information. To make sense of the poster, the viewer would need to process a constellation of visual information. In addition to retrieving information from the textual and graphical content, one should also have sufficient knowledge of the macro picture, or to put simply, what in general is going on. This shared understanding of the situation provides access to an implicit meaning generated by the extended social semiotic network. Imagine a reclusive resident in Antarctic—the single continent unaffected by the virus (UNDP, 2020)—visits the U.S. and saw the COVID-19 posters. Without previously knowing the disease and the crisis it has caused, the visitor, though literate in the English language and had a normal visual ability, may find the posters somewhat baffling. Yet it is not the meaning expressed by the poster that has caused the barrier towards understanding; it is the shared experience and knowledge gained in living through the pandemic that supplies the missing link to successful communication. To an “outsider” who is completely unaware of the situation yet is thrown into the communication unprepared, this whole set of information can be just too ‘decontextualized’ to be meaningful.

This indicates that the relevance of the information being conveyed by the poster depends partially on its situatedness in the broader sociocultural context, without which the conveyance may be hindered or frustrated. Therefore, an adequate account of the meaning-making mechanism of the poster as a communicative genre in a crisis discourse would entail the identification of the factors that help shape the genre as it emerges to be and the way it interacts with the macro discourse of risk communication.

5. Conclusion

This study investigates the communicative genre of posters in the COVID-19 pandemic. With an analysis of a collection of sample posters, it discusses strategic mobilization and combination of semiotic resources and how it helps create interconnections between signs within and beyond the individual context. In the case of COVID-19 posters, the specific designs are characterized by adopting a host of textual and graphic features that contribute to the representation of entity, condition, action, and sentiment. With purposeful assemblages of resources, the poster can be described as a semiotic ensemble where the coordination and collaboration among semiotic resources work to reduce potential ambiguities and amplify the communicative effect of the poster. Thanks to the resourceful designers, these posters add informative and artistic support to motivating public response to the crisis. This study offers only a preliminary view of the poster genre in the COVID-19 crisis context; further research is needed to estimate and evaluate the effect of this distinctive medium of communication to learn more from the experience and provide operational suggestions to professionals.

Notes

1 The COVID-19 poster collection on the Irish government was published by the Department of Health on 11 March 2020 (https://www.gov.ie/en/collection/ee0781-covid-19-posters-for-public-use/).

2 The continuum is but a vague illustration of some of the most common types of posters in use and presents only one possible distribution of the poster types. There are admittedly alternative distributions as the specific scenarios of usage under each label may vary widely in terms of information and style conveyed by the poster.

3 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) is a U.S. national public health institute. As a federal agency, CDC operates under the Department of Health and Human Services. The poster was downloaded from the CDC website entitled “Print Resources Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19)” via the link https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/communication/print-resources.html?Sort=Date%3A%3Adesc where a collection of 81 posters are sorted based on the intended viewership (e.g., the general public, school kids).

4 The poster samples were downloaded from the Regional Office for West and Central Africa website at https://rodakar.iom.int/covid-19-posters.

5 The cross-mark symbol is subject to alternative interpretations, e.g., “X” can be markers of spots on a map. Though it seems that people across cultures tend to agree upon the use of a cross mark for an error, symbols for a correct answer vary. In Asian conventions, Chinese culture endorses the use of a tick for correctness; whereas Japanese culture would prefer the use of a circle mark (“maru”).

6 The emojis are downloaded from Emoji List, v13.0 (http://www.unicode.org/emoji/charts/emoji-list.html) where a list of the Unicode emoji characters and sequences are provided in a chart, with each image entry annotated with code number, short name, and alternative keywords.

7 The word entry is accessed at https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/solidarity.

8 The English word “ensemble” is borrowed from French “ensemble” which means “all the parts of a thing considered together” (https://www.etymonline.com/word/ensemble, accessed August 3, 2020). In music, the word emphasizes the coordination among a group of artists (e.g., musicians, actors, dancers) performing together rather than the role of an individual. In a more general and abstract sense, the word designates a state of “togetherness” as opposed to “separation”, as the part of a group is considered valid only in relation to the whole (https://www.dictionary.com/browse/ensemble?s=t, accessed August 3, 2020).

Language and Semiotic Studies2020年3期

Language and Semiotic Studies2020年3期

- Language and Semiotic Studies的其它文章

- Nigerian Languages and Identity Crises1

- Do Unfamiliar Text Orientations Affect Transposed-Letter Word Recognition with Readers from Different Language Backgrounds?

- A Multimodal Critical Study of Selected Political Rally Campaign Discourse of 2011 Elections in Southwestern Nigeria

- A Multimodal Discourse Analysis of Saudi Arabic Television Commercials

- The Temporality of Chinese from the Perspective of Semantic Relations

- A Study of Natural Elements in French Ecological Writer Jean Giono’s Works