A Multimodal Discourse Analysis of Saudi Arabic Television Commercials

Nuha Khalid Alsalem

Shaqra University, Saudi Arabia

Abstract This study provides a multimodal discourse analysis of Saudi Arabic TV commercials from a linguistic and visual semiotic perspective, linking communication, language, and culture. The study draws on pragmatics, semiotics, and language and culture, within the framework of discourse analysis. The data consisted of five commercials of personal care items, with the analysis focusing on figurative linguistic elements, including metaphorical expressions and personification, as well as visual elements, including visual metaphors and semiotic symbols. The analysis is based on Lakoff and Johnson’s (2003) conceptual metaphor theory, Saussure’s (1966) theory of semiology, and Grice’s (1975) theory of conversational implicatures. The findings contribute to the existing literature on visual and linguistic metaphors and could serve as a foundation for future studies to examine how the interaction between language and visuals in advertising is represented across cultures. It could also have implications for the practice of advertising in international business and marketing communication.

Keywords: discourse analysis, multimodality, commercials, metaphors, personification, semiotics, implied meaning

1. Introduction

1.1 Research background

The language of advertising is multimodal, containing rhetorical figures, visual elements, semiotic modes, and interaction among these resources. Advertising has been frequently studied in business, cultural studies, and communication, yet it has received little attention from a linguistic perspective. In addition, many advertising studies have focused on certain components of an ad while ignoring others. Some describe the pictures in the ad without studying the language of the ad itself, and most linguistic studies on advertising analyze metaphors independent of semiotic symbols or vice versa. Thus, the current research addresses this gap by focusing on how language in commercials (i.e., figurative expressions) complements or departs from the visuals. Yu (2009) observed that “so far there are not many studies focused on nonverbal and multimodal manifestations of conceptual metaphors despite the fact that such studies are theoretically essential to consolidate the validity of conceptual metaphor theory” (p. 137). Although verbal metaphor research has increased over the decades, pictorial metaphor research is limited.

There is considerable metaphor research on English, predominately American English (e.g., Kim & Chung, 2005; Shuo, 2014), but far less on other languages, particularly non-European languages. Although Gully (1996) explored the discourse of magazine and TV ads in Egyptian Arabic, no linguistic analysis has been conducted on commercials in other Arabic dialects, such as Saudi Arabic. Moreover, most studies on Saudi Arabic TV ads have focused on the audience’s perceptions of the content rather than the language of advertising itself. Only a handful of studies on advertising in Saudi Arabic were found. Alibrahim (2017) and Nassif and Gunter (2008) examined gender representation in TV ads, while Al-Makaty et al. (1996) and Al-Kheraiji (1992) considered the content of TV ads from Saudi viewers’ perspectives. Razzouk and Al-Khatib (1993) and AlFardi (1989) discussed the nature of TV ads in general.

All of these studies, however, were designed from a marketing perspective, with little or no linguistic analysis offered, a huge gap the current study seeks to address. In addition, there are fewer studies on TV advertising than on other media, such as print ads. Therefore, there is a need for multimodal analysis of Saudi Arabic TV commercials, drawing on interdisciplinary approaches, including pragmatics, semiotics, and language and culture, within the framework of discourse analysis. By building on prior work and addressing gaps in the literature, this study provides new insight into the modality of TV commercials and how metaphors and semiotic symbols are manifested in Arabic.

1.2 Overview of the study

This study provides an in-depth multimodal discourse analysis of naturally occurring data from five Saudi Arabic TV commercials for personal care items that were retrieved from YouTube. The analysis included the use of figurative linguistic elements—including metaphorical expressions and personification—as well as visual elements, including visual metaphors and semiotic symbols. The study focused on the implicatures (implied meaning) and socio-cultural values the commercials reflected. An interdisciplinary approach was adopted, where multimodality of language and visual elements interacted. I carefully followed steps to ensure the qualitative content analysis was carried out in a valid, reliable manner, based on several theoretical and analytical frameworks.

The conceptual metaphor theory, developed by Lakoff and Johnson (2003), was used to analyze linguistic metaphors. Taking the sentence LIFE IS A JOURNEY as an example, the theory could be described as conventionalized metaphorical ways of understanding a target conceptual domain (e.g., LIFE) in terms of a source conceptual domain (e.g., JOURNEY). Conceptual metaphors consist of systematic sets of mappings across two domains in a conceptual structure (Lakoff & Johnson, 2003). To analyze visual metaphors, I drew from Forceville’s (1996) analysis of pictorial metaphors in advertising. Saussure’s (1966) theory of semiology was also applied. According to him, a sign is used as a conventional representation that consists of a signifier (a word or image) that represents a given concept, called the signified. Grice’s (1975) theory of conversational implicatures was followed to explain the implicatures (implied meaning) of the commercials.

Language and visuals in the ads have been described, interpreted, and explained in light of social context or practice. The ads were translated from Arabic into English, and the analysis for the figurative expressions include the Arabic version, a gloss, a transliteration, and an English translation for each commercial.

2. The Discourse of Advertising

Being multimodal, the language of advertising contains rhetorical figures, visual elements, semiotic modes, and interaction among these resources. Czerpa (2006) compared metaphors in advertisements in the English and Swedish editions of a women’s magazine. She argues that advertisers considered the interests and concerns of the target population. Similarly, she discusses the manipulation of linguistic material in textual advertising. She found that manipulation of the language of ads could be achieved at orthographic, phonetic, morphological, lexical, and sentential levels.

Advertising agencies rely heavily on creative ways to capture the audiences’ attention. Marra (1990), in his bookAdvertising Creativity: Techniques for Generating Ideas, explains the “craft [of ad copywriters and artists] is to generate creative ideas and then communicate them through the words and images we see in ads in the various print and broadcast media” (p. 35). He stated that their job is to “shape and tailor pointed messages in ways that evoke some form of positive intended response from a particular target audience” (p. 35). Advertising ideas should always align with the goals and objectives of the ads. Marra asserted that creativity in advertising means “being new and relevant with your ideas […] being creative or different,” as long as the creativity or difference is connected to the purpose of the ads (p. 35). Advertising agencies encourage their audiences to see things through new and different eyes by being distinctive, and that is what can make the ad successful, innovative and effective. Creative thinking is to think out of the box, to go beyond what is seen as usual or conventional. However, creativity can sometimes cause confusion or distraction to the audience when the message is not interpreted as it is meant by the advertising agency. Therefore, unambiguity and well-comprehension of the advertising are key factors for the effectiveness on the target audience.

3. Multimodality, Visual Representation and the Semiotic Approach

Multimodality has been defined as “the combination of more than one mode or means for communication”; in this sense, “Speech, gaze, gesture, and body posture work together in order to make meaning in spoken interaction. Similarly, writing, images, layout, and colour play a role in the creation of meaning for handwritten, print, or digital texts” (McArthur et al., 2018). The role of rhetoricians and semioticians is understanding the connection between our internal and external world because the latter is based on our senses and mind (Kenney, 2005). Kenney (2005) differentiated between rhetoricians, who are concerned with how humans create symbols to persuade an audience, and semioticians, who deal with how humans interpret signs and symbols. A key concept in both fields is “representation”, that is, “how signs ‘mediate’ between the external world and our internal ‘world’, or how signs ‘stand for’ or ‘take place of’ something from the real world in the mind of a person” (p. 99). Moreover, Foss (2005) defined visual rhetoric as “the study of visual imagery within the discipline of rhetoric” (p. 141). An ancient term, rhetoric refers to what is now called “communication”. Foss added that “the study of visual images continued and, indeed, now flourishes in rhetorical studies [due to] the pervasiveness of the visual image and its impact on contemporary culture” (p. 142).

Language is not the only mode of meaning and communication in any culture. Kress and van Leeuwen (2001) argued that within visual semiotics, multimodality is the use of several semiotic modes and their combination within a socio-cultural domain, which results in a semiotic product or event. It can be used to study any kind of text, verbal or visual, and the social context in which the text was created. They claimed visual images fulfill the metafunctions of representing the experiential world (representational meaning), interacting with viewers (interactive meaning), and arranging visual resources (compositional meaning) to the same extent as verbal language.

In studying signs and symbols, syntagm and paradigm govern how signs relate to one another. The syntagmatic analysis focuses on the surface structure, whereas the paradigmatic analysis examines the deep (embedded) structure. Unlike other linguistic descriptions, Halliday (1985) paid attention to the paradigmatic axis. Therefore, Halliday’s central theoretical principle concentrates on how language works and considers language a social semiotic symbol. Pérez-Sobrino (2016) explained that “visual social semiotics emerged in the 1990s building on Halliday’s Systematic Functional Grammar”. The idea is that when people communicate, they make choices from a set of other choices on which word (e.g., image, clothing) to select. The words we choose each have a special value and specific, contextual meaning. Halliday’s main argument is that language is constrained by a social context.

Semiotic symbols are a type of visual representation. Saussure (1966) defined semiology as “A science that studies the life of signs within society” (p. 16). He offered a two-part model of the sign, consisting of signifier and signified. Philosophers Pierce (1839-1914) and Morris (1901-1979) are key figures in the early development of semiology (Chandler, 1994). Peirce’s model of signs consists of three parts: the representamen, the object, and the interpreter. He categorized the types of signification as iconic, symbolic, or indexical. An image of a flower representing a flower is an example of an iconic sign, which is literal. An image of a woman carrying an umbrella as a clue that it is raining is an example of an indexical sign. A symbolic sign represents something else by convention or by association; for instance, the image of a red heart can represent love and romance.

Based on Peirce’s classification of signs, Morris stated that studying semiotics involves knowledge of three branches of linguistics: semantics, syntax, and pragmatics (Chandler, 1994). Signs differ across cultures because they are socially determined and culturally governed. Chandler (1994) attributed the recognition of semiotics as a major approach to cultural studies in the late 1960s to Barthes (1915-1980). Barthes’ 1957 bookMythologiesgreatly influenced the development of semiotics and increased scholarly awareness of the field. Barthes defined semiology as follows:

Semiology therefore aims to take in any system of signs, whatever their substance and limits, images, gestures, musical sounds, objects, and the complex associations of all of these, which form the content of ritual, convention or public entertainment: these constitute, if not languages, at least systems of significations. (as cited in Chandler, 1994, p. 1)

Thus, using visual techniques is a common practice in ads to increase their persuasive power and influence on the audience.

Van Leeuwen (2001) explained that visual semiotics have two layers of meaning: denotation and connotation. The denotative meaning of images requires a different level of generality, which mainly depends on context, audience, and the goal of the image. Interpreting an image thus depends on its context, and some contexts require extensive reading even to understand the denotative meaning. Connotation consists of ideas, values, and cultural beliefs.

According to Jewitt and Oyama (2001), describing semiotic resources (how visuals are used) and interpreting their meaning together constitute social semiotics analysis of visual communication. Najafian and Ketabi (2011) investigated print ads based on Fairclough’s (2003) critical discourse analysis and Kress and van Leeuwen’s (2006) social semiotic approach. Najafian and Ketabi (2011) focused on the combination of linguistic elements (i.e., syntax) and semiotics (i.e., images) in analyzing the ads. They concluded that “advertising is a crucial factor in the dissemination of ideological values in any social discourse” and “this discourse is mediated, meaning that whatever aspects of social life are represented in the advertising pass through the particular linguistic as well as social semiotic resources” (p. 16).

Several scholars have analyzed signs and semiotic resources in advertisements. Al-Momani et al. (2016), for instance, examined Arabic newspaper ads in Jordan. Their semiotic analysis investigated the sources and communicative functions of intergeneric borrowings based on the sociocultural context. Intergeneric borrowing was defined as a persuasive technique in ads that involved borrowing from different genres and fields of discourse. The study followed a semiotic analysis approach focusing on Barthes’ (1957) view of the interpretation of signs and Chandler’s (1994) framework of semiotic analysis in a simplified version relevant to their topic. Al-Momani et al. (2016) identified five sources of intergeneric borrowings: borrowing from popular culture, from mundane situations, from religious discourse, from cultural memory, and from scientific discourse. Borrowings from different sources could seem irrelevant to the product advertised but still carry connotative meanings. Overall, the analysis strongly argued that borrowings in the ads carried social meanings derived from viewers’ sociocultural and ideological repertoire. Thus, for symbols to achieve their communicative purposes in advertisements, cultural knowledge would be necessary.

Akpan et al. (2013) examined the communicative values of symbols in Nigerian print ads via two methodological approaches: a qualitative content analysis and a survey. The study investigated the signifier-signified relationships in the iconic, linguistic, and ideological values of the elements of the products they analyzed. To carry out the content analysis, they examined 10 print ads from a Nigerian magazine and established five content categories: linguistic, semantic, pragmatic, and syntactic values and ideological appeals. The analysis focused on selected parts of the ads, including the headline, sub-headline, body text, illustrations, pictures, logotypes, word marks, and slogans. They reported results similar to those of Al-Momani et al. (2016) regarding the importance of symbols conforming to the social norms of the target audience, which can then be viewed positively by the consumers and affect their decisions. Akpan et al. (2013) concluded that advertisers “must pay great attention to the symbols they wish to utilize in order to meet their basic marketing objectives, without offending or confusing the prospective or actual customers, and also, without harming instead of valorizing their products and services” (p. 21). In short, for semiotic symbols to be effective, advertising agencies should consider the target audience, what they value, and relevance of these symbols to both audience and advertising message.

4. Women-Oriented Product Studies

Ads designed to appeal to women about products, such as personal care items, beauty, and fashion, are ubiquitous. With a surge of interest in adverting discourse research, there have been many studies on women-oriented advertising. Czerpa (2006) examined metaphors in English and Swedish women’s magazine ads. Metaphor, metonymy, and personification played a major role in both languages. For example, the data showed many examples of PRODUCT IS A HUMAN, in which the product shared human features. Although the ads were similar in the two languages, there were some differences. The English ads contained more visual elements, focused on the effect more than the function of the product, and built on emotional and physical pleasure, and the informativeness of the ad depended on the product if it involved detailed steps. On the other hand, Swedish ads focused on function over effect, and visual elements were not clear because they lacked supporting textual elements, but the ads were still considered more informative than their English counterparts.

Baykal (2016) conducted a detailed multimodal analysis of six mascara ads collected from Turkish magazines within the framework of critical discourse analysis. She explained how verbal and visual strategies were used to represent an ideal look of a woman. Besides analyzing linguistic choices, she examined the interplay between visual and verbal communication patterns. The main linguistic feature in her data consisted of positive adjectives with their comparative or superlative forms. A social implication of the study was that women should deal with their bodies in a way that is approved by their culture. She concluded that advertisers used language and visuals to influence women to buy things they might not need. For instance, “The ‘ideal’ woman is represented by stereotypical visual and textual components in advertisements guiding how particular body parts should look to reach the ideal” (p. 56). Although Baykal dealt with print ads, her study provided an insightful analysis of how multimodality is achieved in TV commercials as well.

Ads targeting women tend to focus on the emotional level. Shuo et al. (2014) examined the reason for emotional appeals in women’s ads using corpus linguistics and critical discourse analysis. They referred to Bernstein (1974), who identified two distinctions in modern marketing strategies: reason advertising and tickle advertising. The former focuses on motives for buying and the latter is about using humor or mood for emotional appeal. Part of Halliday’s (2000) systemic-functional linguistics for identifying the function of language deals with six main process types (as cited in Shuo et al., 2014). Halliday examined material and mental processes because they can reflect the appeal type directly. The material process contains verbs that have reason appeals, such as the description of products, whereas the mental process includes verbs related to senses, feelings, and thoughts.

To examine these appeals, Shuo et al. (2014) performed quantitative and qualitative analyses of vocabulary in popular English women’s magazines. The data included 50 ads about fashion and beauty. Despite the stereotype that ads targeting men include more material process than women’s ads, the results showed the magazines contained more reason appeals (70%) than emotional appeals. They explained that the ads should provide enough information, such as shape, size, function, and effect, for the target buyers to decide whether to make a purchase. Women receiving the same education opportunities as men meant that strategies for material process influenced the design of modern advertising (Shuo et al., 2014). The ads used certain strategies to make the products more attractive, such as figures, collocating material and mental processes, listing facts about the products, and contrasting them with similar products.

Figurative expressions have been found in ads for women. Kelly (2016) conducted a cross-cultural study comparing cosmetic metaphorical expressions in Chinese and English advertising slogans. She stated that many previous studies on metaphors were based on Lakoff and Johnson’s conceptual metaphor theory, but few had analyzed metaphors by combining critical discourse analysis with other approaches. Therefore, she adopted Charteris-Black’s (2004) critical metaphor analysis framework. Kelly (2016) found common features between English and Chinese ads, such as positive adjectives and nouns. Positive adjectives highlighted the high quality of the products and built an ideal image for consumers. Metaphors in slogans influenced women “by lowering consumers’ self-perception and portraying the appealing and successful women with pretty face, slim figure, and fair skin like celebrities” (p. 145). Metaphorical expressions in Chinese ads more implicitly focused on a mother’s love and emotional intimacy with physical closeness like touching, while English slogans emphasized taste and personality. Overall, the results showed critical metaphor analysis can provide a more comprehensive view of advertising discourse by building on cognitive linguistics within a critical paradigm.

5. Findings

This section discusses the findings on multimodality in five Saudi Arabic TV commercials for personal care products. All the commercials contained figurative expressions, visual metaphors, or both. Since the items examined had a female target audience, all ads in this category used feminine pronouns, even for unisex products. Products like personal care items are viewed as feminine by men, because of Arab society’s ideal of masculinity. Another explanation for these commercials not addressing men is that women commonly buy such products for their husbands, or men could share their wives’ products and thus rely on women to buy them.

A notable observation was that the commercials did not reflect everyday Saudi cultural practices; they were meant more to evoke emotions on a universal level. One reason for this finding is that most of the products in this category were not from local companies aware of the cultural norms and expectations of Saudi Arabia. Thus, this result highlights the challenges of local and international advertising campaigns. Not reflecting a cultural practice of a society does not necessarily yield negative results, especially for Western personal care and cosmetics that are preferred by local women. This finding also showed the significant role of celebrity. These results coincided with Chan and Cheng’s (2012) finding that Hong Kong women were more influenced by ads using foreign models and Western beauty trends. Nevertheless, messages that carry cultural components can better aid comprehension and interpretation of the implicatures of ads.

Thus, this study challenges previous findings that positive attitudes toward ads reflect the cultural norms of a society (e.g., Akpan et al., 2013; Al-Momani et al., 2016; Gully, 1996) since product type may significantly influence the extent to which positive, neutral, or negative attitudes reflect cultural norms. In addition, more research about consumer perceptions is needed on subtle differences within cultures, as cultural schema, shared knowledge, and context play a significant role in interpreting utterances in social interactions. As some researchers take a broad definition of culture, future studies can shed light on pragmatic variation and how sub-cultures within a community perceive commercials by investigating cultural complexity. Interpreting an utterance is part of one’s mental representation, so people interpret utterances differently due to their different personal experiences and knowledge about the topic. Factors that vary within cultures—such as age, gender, and socioeconomic status—play a huge role in communication. These differences can explain the variation within a culture when interpreting a message.

The product category includes five TV commercials on personal care items. The longest commercial was 50 seconds long, and the shortest 15. The average length was 28 seconds. The following sections provide an analysis for each commercial as a case study. At the beginning of each analysis, a description is provided independent of the researcher’s interpretation.

5.1 Commercial 1: Sunsilk shampoo (Sunsilk Arabia, 2016)

A song is used to present the problem of damaged hair and to suggest a way to repair it. The Turkish-German actress Meryem Uzerli performs in the ad. The song goes, “I can’t believe what’s happening to my hair, this is forbidden. It dries and breaks again, and I need a solution.” The ad shows the actress trying to comb her tangled hair. She is disappointed and goes to a salon, where a male stylist suggests a shampoo. After using it, the actress seems happy and the song goes, “Wow, life has come back to my hair. It’s been a while since I’ve felt happy about myself. Nothing will damage my hair. With you, Sunsilk, life is sweet.” The outdoor setting, balloons, swing, and colorful outfits of the models in the ad are used to indicate liveliness and energy. There is a focus on facial expressions and body language.

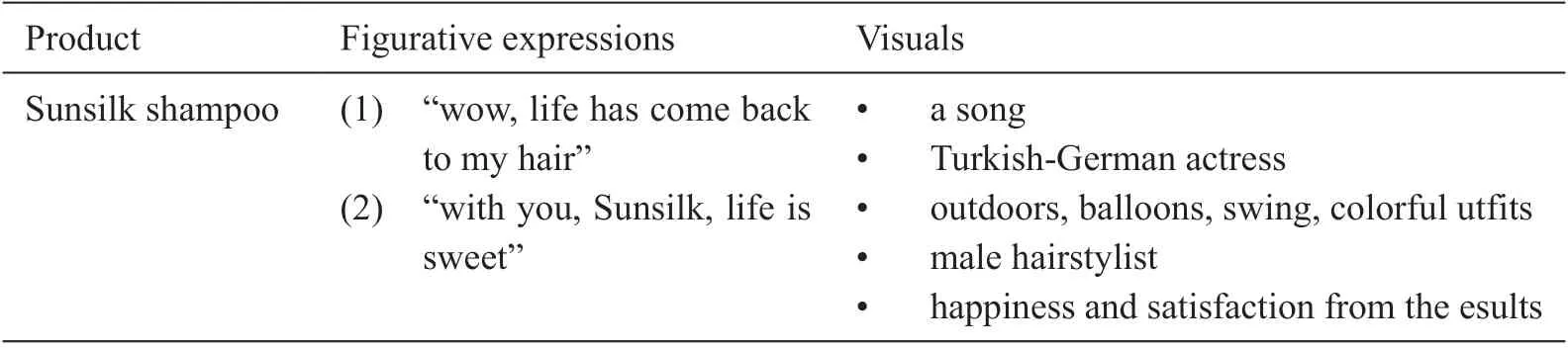

Table 1. Figurative expressions and visual elements in Sunsilk shampoo commercial

In (1), the figurative expression is HAIR IS A HUMAN BEING. Hair is metaphorically personified as coming back to life, as both people and hair need life.

In (2), there is an example of personification: A PRODUCT IS A PERSON. The product Sunsilk is personified as a lover or romantic partner. The idea is that using this product is like being with someone who makes life sweet. Life is also compared to a food, LIFE IS FOOD, by being given a sweet taste because usually people like eating sweet things. Therefore, to better describe life as an abstract concept, a common source domain used in everyday cases, such as food, is used. Additionally, the Sunsilk brand is referred to in the second person (you), which directly and explicitly suggests it is a person and strengthens the personification. Although (1) and (2) are verbal metaphors, they are supported by visuals to emphasize their meaning. For example, Figure 1 shows the woman smiling with the shampoo in the background as if she is in a happy relationship.

The ad uses music that goes with the freshness of the product. Women in Saudi Arabia only go to female hairstylists, yet the commercial can still appeal to many Saudi women because they can use the product regardless. The ad does not reflect Saudi cultural practice but uses a technique that connects celebrity with a modern lifestyle (Chan & Cheng, 2012). The Turkish-German actress was chosen because she won several awards recently and many people who watch Turkish drama know her, as Turkish TV shows have become popular in the Middle East, including Saudi Arabia. The ad focuses on celebrating the results of the product.

Figure 1. Visuals in Sunsilk shampoo commercial

5.2 Commercial 2: Pantene shampoo (Pantene, 2017)

The ad shows a woman in a spacious room with white walls and long white curtains hanging from the ceiling. The woman is wearing a black suit, which stands out from the white background. The ad starts with a woman hanging from one of the curtains and waving her hair in the air. She is holding the curtains tightly, suggesting both the curtains and her hair are strong. The voiceover states, “Long hair’s strength is in its volume, neither light nor weak. Pantene, with its unique formula containing protein provitamins, enters deep to increase volume and strengthen hair from the roots to the ends.” While the voice talks, the woman is hanging and swinging from the curtains. She also makes a tight knot in the curtains, saying, “Strength is beautiful.”

Table 2. Figurative expressions and visual elements in Pantene shampoo commercial

In (3), a visual metaphor HAIR IS CURTAINS is used to compare hair to curtains in terms of strength and volume (see Figure 2). In addition, hanging from the curtains and making a tight knot suggests the hair is strong, healthy, and resistant to breakage like the curtains.

Figure 2. Visual comparison in Pantene shampoo commercial

5.3 Commercial 3: Dove hair conditioner 1 (Dove Arabia, 2018)

The ad opens with a woman holding two white roses, one in each hand. The narrator says, “Dove conditioner is able to prove that it stops hair damage even before it happens.” The woman puts each rose in a glass of conditioner, one labeled “protected with Dove conditioner” and the other “unprotected”. Then she puts the roses in a glass of water to wash them and places each flower in a vase to expose them to damaging heat from blow dryers. The one protected by Dove conditioner stays stable and resists the heat, while the other becomes dry and brittle, changing from white to dull yellow and drying out. The woman holds the two flowers and shows the one not protected by Dove breaks, whereas the other looks fresh and nice. The narrator says, “Dove conditioner strengthens hair and stops 90% of damage.”

Table 3. Figurative expressions and visual elements in Dove hair conditioner commercial

The ad provides a visual comparison between hair and roses, HAIR IS A ROSE. In (4), hair is represented by a white rose; both are delicate and need protection (see Figure 3). The ad uses the same adjectives used with hair to describe the roses, such as when the woman soaks the roses in a glass of conditioner and exposes them to heat. The blow dryers are another symbol comparing the roses to hair. Roses are symbolic. Comparing hair to roses gives women an impression that their hair is special and needs careful attention. The commercial’s message is that this brand of conditioner can fulfill this role.

Figure 3. Visual comparison in Dove conditioner 1 commercial

5.4 Commercial 4: Dove hair conditioner 2 (Dove Arabia, 2017)

The ad starts with a question posed to the viewers: “Will your hair survive the damage test?” It shows a woman straightening her hair with a flat iron. The ad answers the above question by saying, “Yes, with Dove conditioner, it will.” The narrator talks about an experiment with two soft orchid roses in which only one of them is protected by Dove. They soak the two roses in a glass of conditioner, one Dove and the other a different brand. Then they expose both roses to the same heat temperature of the flat iron. The difference is clear. The flower not protected by Dove dries out and breaks. The narrator talks about the benefits of Dove conditioner, which “nourishes the hair deeply, makes your hair stronger, and protects it from daily damage”.

Table 4. Figurative expressions and visual elements in Dove hair conditioner commercial

In (5), women’s hair is compared to an orchid, with both being special and delicate (see Figure 4). The choice of an orchid could be due to its symbolizing femininity. In addition, orchids have a unique appearance. This may imply that women’s hair types are different the same way that orchids are different, but each has a special beautiful look.

Flat ironing is a common hairstyling technique. In Saudi culture and many other cultures, long silky black hair is viewed as beautiful. The ad suggests that using this product will prevent breakage due to the heat from ironing.

Figure 4. Visual comparison in Dove conditioner 2 commercial

5.5 Commercial 5: Olay moisturizer (Olay Arabia, 2016)

The ad opens with a woman looking at her face in the mirror, and a female voiceover says, “Do you need a youthful look but hate feeling oily?” The voice introduces the new Olay Total Effects Feather Weight Moisturizer as a feather falls next to the bottle of moisturizer. “It fights the seven signs of skin aging with its light texture and quick absorbance.” The ad shows a woman with her daughter blowing feathers and placing a feather on her daughter’s face, with the voiceover, “It’s now light as a feather. Your skin won’t reveal your age anymore.”

Table 5. Figurative expressions and visual elements in Olay moisturizer commercial

In the figurative expression in (6), the moisturizer is compared to a feather in their lightness and softness. In addition, placing the feather on the girl’s face indicates that both are soft, the same quality as the moisturizer.

Figure 5. Visual comparison in Olay moisturizer commercial

Although this commercial does not reflect Saudi cultural practice, it assumes women’s general knowledge about personal care products. Using the feather as a semiotic symbol and in the figurative expression requires background information on the viewer’s part. Since this product is intended for women, some women prefer light moisturizer because the skin absorbs it quickly and does not feel greasy or develop blocked pores, which could cause skin problems. Men who view this commercial may not get the implied meaning of using a feather to describe the moisturizer.

6. Conclusion

Overall, the visuals and language of the ads complement each other, suggesting a strong interaction between linguistic and visual modes in the discourse of advertising. Language and visuals both carry literal and figurative meanings. Another implication is to consider the semiotic symbols in the ads while identifying and analyzing metaphors. A gap in the literature is that many advertising studies have focused on certain components of an ad while ignoring others. Some studies describe the pictures in the ad without studying the language. In addition, most research in figurative language examines metaphors independent of semiotic symbols. However, this study showed it is important to consider the social semiotic symbols as they construct the meaning along with the metaphors. Even if the semiotic symbols are not part of the visual metaphor itself, they still provide a strong context to better introduce, shape, and comprehend the implied metaphorical meanings. This study examined the interaction between figures of speech in multimodal TV commercials featuring language and visual elements. As only a few studies on advertising in Saudi Arabic were found, especially from a linguistic perspective, this study contributes to understanding how figurative language and semiotic symbols are manifested in Arabic in this context and how cultural values shape the figurative expressions and visuals used.

The findings could be supplemented by a confirmatory study with the same research goal but a larger size of sample commercials. Moreover, if commercials of other product types, such as food, appliances, health, sports, and other services are included, different results may be yielded that could help analyze the language of advertising. A contrastive analysis could be conducted in other languages for the same products if a company was advertising internationally. This line of inquiry would examine how figurative language (if any) worked in advertising in other languages, and cross-cultural studies could contribute to the growth of the field.

Language and Semiotic Studies2020年3期

Language and Semiotic Studies2020年3期

- Language and Semiotic Studies的其它文章

- Semiotic Resourcefulness in Crisis Risk Communication: The Case of COVID-19 Posters

- A Multimodal Critical Study of Selected Political Rally Campaign Discourse of 2011 Elections in Southwestern Nigeria

- Do Unfamiliar Text Orientations Affect Transposed-Letter Word Recognition with Readers from Different Language Backgrounds?

- Nigerian Languages and Identity Crises1

- A Study of Natural Elements in French Ecological Writer Jean Giono’s Works

- The Temporality of Chinese from the Perspective of Semantic Relations