海草植株扩繁理论及其定植效应的研究进展*

张沛东 张彦浩 张宏瑜 张秀梅

海草植株扩繁理论及其定植效应的研究进展*

张沛东①张彦浩 张宏瑜 张秀梅

(中国海洋大学 海水养殖教育部重点实验室 青岛 266003)

海草(Seagrasses)是地球上一类经陆生植物演化,发展到可以完全在海洋环境中生活的高等被子植物,具有重要的生态功能和经济价值。本文综述了近年来国内外对海草植株扩繁理论及其定植效应的研究进展,总结了影响海草植株生长扩繁的环境因素,探讨了定植间距、定植阶段、施肥处理等定植理论和技术对海草植株定植效应的影响,并对目前存在的科学问题进行归纳总结,就未来我国沿岸受损海草床生态系统的规模化修复研究提出了展望。

克隆生长;生态因子;植株定植;海草

海草(Seagrasses)是地球上一类经陆生植物演化,发展到完全适应海洋环境的高等被子植物,其一般分布于沿岸的潮间带或潮下带浅水区(Short, 2007; Lopez, 2011)。构筑的海草床是浅海三大典型生态系统之一,具有极其重要的生态功能和经济价值,被称为海洋环境的“生态工程师”,具有强大的水质改善作用和高效的固碳能力(Mcleod, 2011; 高亚平等, 2013),同时,也为众多海洋生物提供重要的食物来源、栖息地、产卵场、育幼场,甚至病原细菌的生物屏障(Lamb, 2017; 吴亚林等, 2018)。然而,受人类活动和自然环境变迁的影响,全球绝大多数海草床均处于严重的日益衰退趋势,仅1993~2003年全球海草床已有2.6×106hm2退化(Martins, 2005),自1879年首次记录海草床面积以来,据估计已有超过5.1×106hm2的海草床完全消失(Waycotta, 2009)。

随着海草床退化的日趋严峻,有关海草床生态恢复理论与技术的研究逐渐受到国内外学者的重视。截至目前,海草床的恢复手段主要包括生境恢复法、种子法及植株移植法,其中,植株移植法又可细分为草块法、草皮法和根状茎法(Goodman, 1995; Li, 2010)。植株移植法是目前应用最广泛的修复方法,然而,目前海草苗种人工培育理论和技术尚不成熟,供体植株均采自天然海草床,不仅对供体草床可能会造成较大的负面影响,而且还限制植株移植的规模化发展。因此,研究海草植株人工扩繁理论和技术,实现供体植株的高效人工培育,对建立生态友好型的海草植株移植理论和技术至关重要。

本文综述了近年来国内外对海草植株扩繁理论及其定植效应的研究进展,概述了影响海草植株扩繁生长的环境因素,探讨了植株定植理论和定植技术对海草植株定植效应的影响,并对目前存在的科学问题进行归纳总结,以期为我国沿岸受损海草床生态系统的规模化修复提供理论参考。

1 海草植株扩繁理论研究进展

1.1 海草植株扩繁的理论基础

植物的生殖方式分为有性生殖与无性生殖。有性生殖为植物的种子生殖,无性生殖包括分株、克隆等,是植株扩繁技术的理论基础。

Busch等(2010)研究发现,利用种子生殖对水生植物进行扩繁的效果并不理想,种子成活率约为10%,这也成为利用种子实现植株扩繁的限制因素。对于水生植物的组织培养研究相对较少,且利用组织培养方式对海洋植物的扩繁困难较大,仅在菹草()和凤眼莲()等种类实现了组织扩繁(高建等, 2006; 李学宝等, 1997),而采取碘化钾对鳗草()叶片组织进行消毒,污染率达46%,难以达到完全无污染(刘延岭等, 2013)。通过酶解获得的鳗草原生质体成活率可达85%,但在后期培养过程中,分裂率极低,只有极少数原生质体出现凹陷并分裂出少量细胞团(崔翠菊等, 2014; Balestri, 1992)。于函(2008)研究发现,海草组织培养使用的消毒液易通过气道进入组织内部,损害外植体,导致愈伤组织诱导率降低且质量差,外植体移入培养基后,易出现褐化现象,影响培养材料的生长和分化,严重抑制愈伤组织的诱导效果。这些因素均严重限制了海草的种子扩繁或组织扩繁。

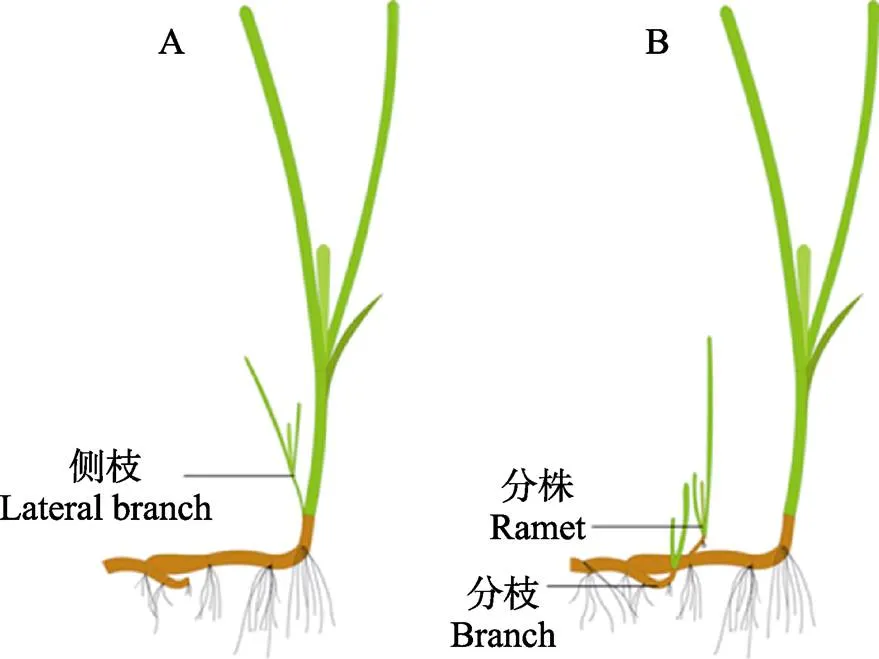

通过无性生殖达到海草种群的持续性维持、更新及扩张是海草床自我维护和自我发育的主要机制,主要有2个方式(图1):(1)分枝型克隆,在母株最靠近地面处的茎节外形成侧枝,母株与侧枝、分株之间可进行营养转移;(2)根状茎型克隆,母株的根状茎伸出横走茎,横走茎的每一个茎节均可长出若干根,进而生成完整的新植株,且理论上横走茎能够无限生长(原永党等, 2010)。海草植株侧枝、分株、分枝的产生可有效促进植株产量的提高,根状茎的频繁分枝克隆,将更多的资源投入到水平扩展中,从而获得较高的植株密度(Watanabe, 2005)。

图1 海草植株分枝型克隆(A)与根状茎型克隆(B)

在资源分配策略上,海草将近90%的种群总生物量分配于地下组织和营养枝,进一步表明克隆生长在其种群繁殖中占有重要地位(李乐乐等, 2015)。澳洲波喜荡草()的分株重量可达 183 mg DW/shoot,卵叶喜盐草()的分株频率达到0.5分株/株(Duarte, 1991);南极根枝草()的垂直茎分枝率可达3.8%,龟裂泰来草()的根状茎分枝率达5.8%(Marbà, 2003)。由此可见,海草通过植株的无性生殖实现其种群的维持、更新以及扩张是至关重要的。

因此,通过促进海草植株的无性生殖,实现植株高效率的分株与分枝,从而增加植株产量与植株密度,是实现植株高效扩繁的首要任务。环境因子对植物扩繁具有极其重要的作用,因此,充分了解环境因子对海草生长发育的影响,查明其生理响应过程,是建立高效的海草植株扩繁理论的关键。

1.2 海草植株扩繁的环境适宜性

海水环境因子,如温度、光照、盐度、营养盐、CO2、底质、水流流速等对海草的存活与生长起关键性作用。

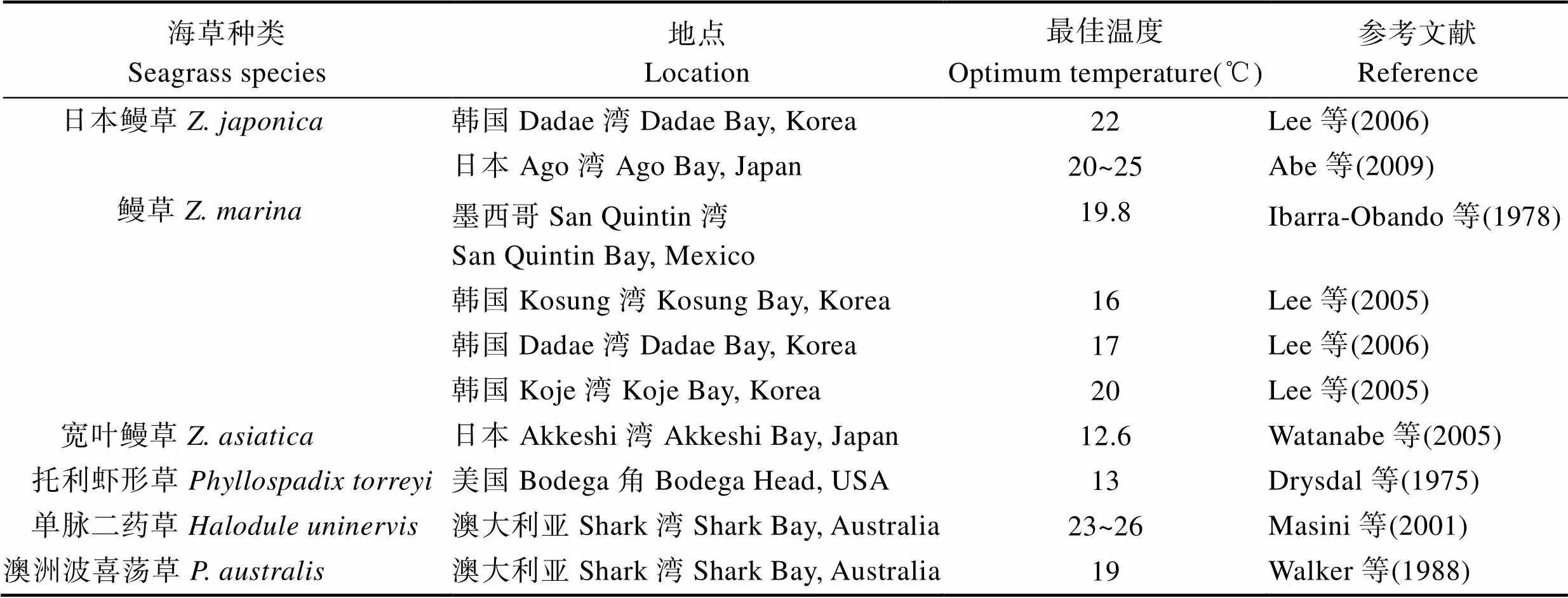

1.2.1 温度 温度影响生物的生理生化过程,是控制海草存活与生长的关键因素(Lee, 2007)。温度在水生生态系统中具有较高的可预测性,对于季节性海草的生长发挥着重要作用。Biebl等(1971)研究发现,温度首先通过影响植株的光合作用,进而影响植株的生长;其次,温度可以调节植株叶片的气孔闭合及光合色素含量,进而调节植株的呼吸作用及光合作用,最终影响植物生长(Robertson, 1984)。不同海草种类对环境温度的变化表现出不同的适应能力,其适宜生长温度见表1。

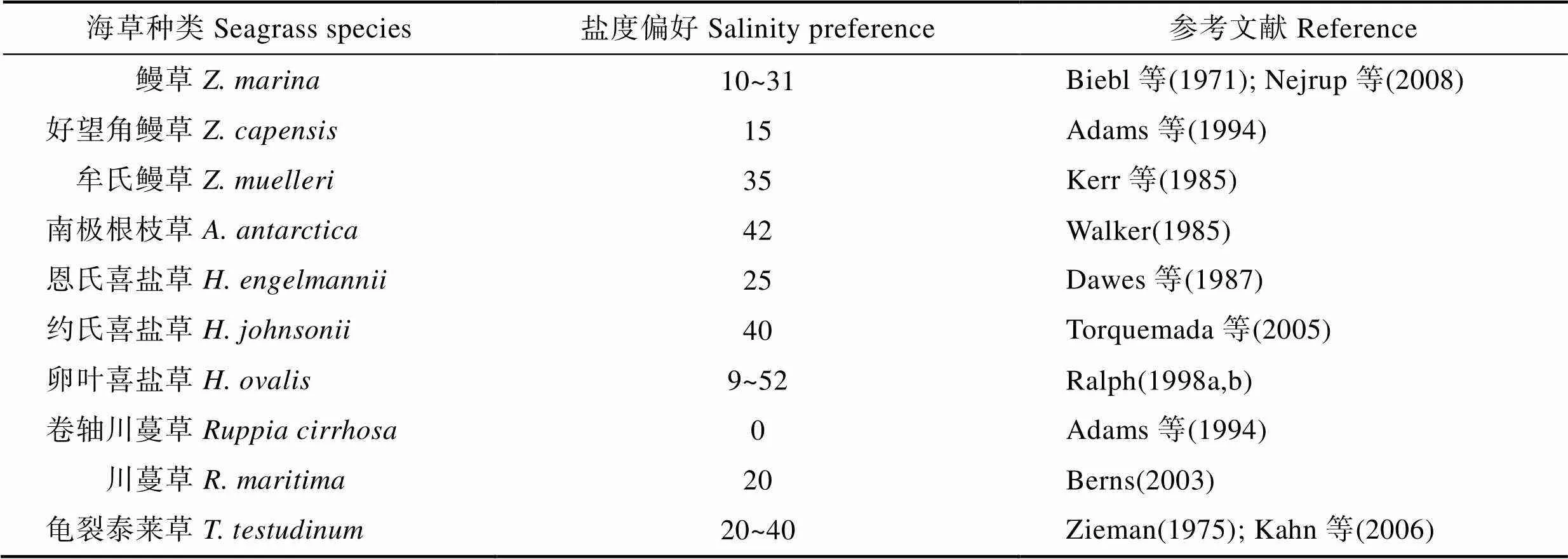

1.2.2 盐度 盐度是影响海草存活与生长的关键因素。海草一般具有较强的盐度耐受能力,特别是对低盐度具有较强的耐受能力,可在盐度为 5~35 的范围内正常存活和生长(Nejrup, 2008),但多数种类的盐度偏好存在较大差异(表2)。从表2可以看出,海草对盐度的耐受性主要包括形态、生理及分子3个层面(邓文浩等, 2018)。形态方面主要包括与海水直接接触且具有一层显著增厚的细胞壁叶片以及根部表皮细胞具有的细胞壁增厚结构(叶春江等, 2002)。生理方面包括渗透调节以及酶的耐受性。研究发现,鳗草通过无机离子与有机溶质的共同作用完成其渗透调节,即盐度的耐受性是多种物质共同作用的结果。从海草植株体内提取的 PEP 羧化酶对盐度具有很高的抗性(叶春江等, 2002),说明海草对盐度的耐受性在一定程度上是因为其体内的酶具有耐盐性。此外,海草植株体内不同类型的细胞之间出现离子区域化,即由光合细胞向薄壁细胞转运,对海草的盐度耐受性也起到重要作用(叶春江等, 2002)。分子方面的研究发现,鳗草叶片质膜表面存在Na+/H+逆向转运蛋白,可维持细胞内部较高的电化学梯度,对海草盐度耐受性至关重要(Fernández, 1999)。Kong等(2013)研究发现,鳗草叶片组织在不同盐度胁迫下的全长cDNA文库中存在与耐盐相关的功能基因,这为海草的耐盐机制提供了理论基础。然而,过低的盐度诱导海草植株光合速率和与之相伴的无机碳含量显著下降,进而导致植株生长变缓,甚至死亡(Mazzella, 1986)。

表1 不同种类海草的适宜生长温度

Tab.1 Optimum temperature for growth of different seagrass species

表2 不同种类海草适宜生长的盐度偏好

Tab.2 Salinity preferences for suitable growth of different seagrass species

1.2.3 光照 光照对海草的生长与分布等具有至关重要的作用。光照主要影响海草的光合作用,植物体内的叶绿素、叶绿素通过对光的吸收,进行C3、C5等一系列生化反应,制造有机物,进而影响到海草的生长。其中,光照周期、光质及光照强度是影响海草生长的关键因素。

1.2.3.1 光质 光质与海草光合色素含量密切相关。光敏素(Phytochrome)、向光素(向光蛋白, Phototropin)和隐花素(Cryptochrome)等光受体在植物体内接受光信号,并通过信号转导,调节植物的生长发育(许大全等, 2015)。植物进行光合作用最有效的光质是蓝光和红光,在水环境生态系统中,光线透过海水时,大部分红光被吸收,仅有少部分蓝光被吸收,因此,与红光相比,蓝光更具有穿透能力。也有研究表明,海草在蓝光条件的生长状况优于自然光条件,因为蓝光更能引起植物叶片气孔的开放,且蓝光的效能几乎是红光的10倍,处于蓝光下的植物细胞色素浓度高,以每分子叶绿素计的光合速率高(Sharkey, 1981; Wilhelm, 2010)。

1.2.3.2 光照强度 光照强度对植物光合作用的影响至关重要。海草植株光合效应模式与陆生植物没有本质区别。适宜光强范围内增加光强,激发植株体内的中心色素(P)对光能的捕获,成为激发态(P*),激发态的中心色素通过连续不断的氧化还原,完成光能到电能的转化。

Ochieng等(2010)研发发现,在100%表面辐射照度下,鳗草的茎节长、茎节数等显著高于34%表面辐射照度。南极根枝草和狭叶波喜荡草() 2种海草的最低表面辐照度均为24.7% (Dennison, 1993);鳗草生产力呈季节性动态变化,达到最大光合速率所需的饱和光照强度为100~ 200 μmol photons/m·s(Lee, 2005)。因此,在人工环境下开展海草扩繁,营造海草生长所需的饱和光照强度条件,对于提高海草净光合作用效率,增加海草植株密度具有重要作用。

1.2.3.3 光周期 光周期通过影响植株体的生长,调节物质含量影响植株的生长发育。刘磊等(2005)研究发现,光照16 h时,可显著提高植物体POD活性;光照24 h时,则显著增加赤霉素(GA3)含量和降低脱落酸(ABA)含量(Woolley, 1972)。因此,适宜的光照周期可提升植物的生理适应能力,促进植物生长。光周期还影响植物根系对营养元素的吸收,诱导与生长有关基因的表达(Torrey, 1976; 任永哲等, 2006)。

有关光周期对海草生理学特征影响的报道较少。Dennison等(1985)在光饱和强度条件下于浅水区域进行实验,结果表明,光照时长减少2.9~4.7 h,鳗草植株最大净光合速率和叶片叶绿素含量提高至对照区植株(光照时间未发生变化)的2倍,而当增加光照时间3.4~4.6 h,其最大净光合速率比对照区植株减少33%。

1.2.3.5 营养盐 营养盐是限制海草生长及生物量的关键因素。海草对营养盐的吸收主要是通过逆电化学需能的化学过程(Fernandez, 1999)。其中,对于NO3–的吸收主要是通过Na+相偶联的机制完成(Garcia-Sanchez, 2000)。对NH4+的吸收则依托氨转运蛋白完成,同时,从土壤吸收NH4+与根部对NH4+排放形成氨氮(NH4+-N)转运体系的动态过程(Ludewig, 2006)。植物体可直接从外界吸收无机磷,经转运蛋白作用运输至木质部,一部分在木质部得到积累,另一部分运输至叶片供植株生长(Loughman, 1957)。Ferdie等(2004)研究表明,充足的氮源和磷源能够促进海草生长,增加海草侧枝数量。此外,营养盐增加还可促进海草根与叶片的N含量、地上与地下组织生物量的提高(Han, 2017)。不同海草种类,其适宜的营养盐含量也不同。当水体中NO3–+NO2–含量达0.27~0.64 μmol/L 时,大洋波喜荡草() 生产力可达3.8~9.4g DW/m·d(Ruiz, 2003);水体NH4+浓度为0.1~6.0 μmol/L时,日本鳗草生产力达到(1.7 ± 0.2) g DW/m·d(Lee, 2006);水体NH4+-N含量超过1.5 μmol/L时,鳗草组织的谷氨酰合成酶活力提高2倍(Touchette, 2007);随环境N浓度增加,莱氏二药草()叶片组织的叶绿素含量随之增加(Jr Heck, 2006)。

1.2.3.6 其他因子 底质是海草根部吸收营养物质的来源,因此,底质的性质影响海草的生物量及分布。有研究表明,当底质的泥沙重量比达到3∶1时,鳗草表现出最佳的生长效果(Zhang, 2015)。从分布角度来看,鳗草较多生长于泥与泥沙底质,而丛生鳗草()大多生长在沙与砾石底质中(江鑫等, 2012)。

重金属对植物的影响主要是通过破坏叶绿体膜和类囊体膜的超微结构,使植物的光合效率降低。当海水Cd浓度>8.9×10–6mol/L,海草在其中存留超过5 h,其叶绿素、叶绿素含量均明显下降(Ralph, 1998a,b)。

综上所述,海草适宜性生长因子是海草植株扩繁的理论基础。对植株的科学定植则是提升海草植株扩繁效果的关键。

2 海草定植效应提升理论与技术的研究进展

将人工培育的实生苗或幼苗移栽至有限的自然环境进行植株自然扩繁的过程,即为定植。通过选定适宜的定植间距和定植时间以及人工施肥等措施,促进定植苗种的生长和扩繁,实现扩繁效率高、生长速度快且节约成本的培育目标,即为定植效应。待定植苗生长至适宜移植的植株规格,即可开展后续的植株移植工作。

2.1 定植间距

定植间距是影响植株生长与分株扩繁的关键因素,适宜的定植间距有助于植株对光照的充分利用,提升植株光合效率及扩繁效力。截至目前,对于沉水植物株距、行距与植株分株、生长等关系未见报道。有研究发现,海草植株的移植单元越大,植株成活率越高,但移植密度增高,植株间竞争力增大,则不利于植株扩繁(van Keulen, 2003; van Katwijk, 2009)。

2.2 定植时间

定植时间与植株的生长发育进程息息相关。适宜的定植时间可有效促进植株的高效扩繁。多数研究针对物候变化进行定植,如邱广龙等(2014)研究表明,干季定植日本鳗草,其成活率高于雨季,在非生长季节(11月~翌年1月)定植日本鳗草,其成活率(86.3%)远高于生长季节(4~10月);刘燕山等(2015)在4~9月分批次定植鳗草,结果发现,7~9月定植的鳗草植株成活率最高(100%)。

2.3 施肥

底质施肥可有效改善植株生存所需的营养物质,保持土壤肥力,有助于提高植株生物量和植株存活率。Balestri等(2014)对小丝粉草()进行海区底质施肥发现(肥料N∶P=13∶6,平均每株1 g),施肥区植株的生物量和密度均显著高于自然区域植株;Sheridan等(1998)对莱氏二药草进行海区施肥处理(肥料N∶P= 14∶14,平均每个草块5.25 g)、Peralta等(2003)对鳗草进行海区施肥处理(肥料N∶P = 1∶4,30、50 mg N g /DW)发现,2种海草的植株密度与未施肥处理组相比均显著增加;La Nafie等(2013)对卵叶喜盐草和单脉二药草()进行海区施肥处理(肥料N∶P∶K=18∶9∶3,2 kg)发现,2种海草的植株高度均显著高于未施肥海区的植株高度。由此可见,合适的肥料种类与正确的施肥方式可明显促进海草植株的扩繁生长。

3 问题与展望

海草植株移植修复法是目前应用最广泛的一种海草床退化生境修复技术,但移植的供体植株均来自天然草床,对供体草床破坏性较大。因此,海草植株移植修复策略的关键是用尽量少的供体植株,实现其高效人工扩繁,达到修复与保护双赢的修复效果。当前,亟待解决的科学问题是如何利用海草植株克隆繁殖这一特性,建立植株高效扩繁理论和技术,并通过适宜的陆海接力方式,达到最佳的海草供体植株扩繁效果。尽管目前有关海草水温、盐度、光照强度和营养盐的适宜性研究已有较多报道,但针对光照周期、HCO3–浓度、光质等环境要素对海草生长扩繁影响的研究还很少,系统的海草植株扩繁理论尚未建立。此外,有关定植间距、定植时间、施肥等海草植株定植理论和技术亦非常薄弱。

针对目前存在的主要问题,急需开展的重点工作主要包括:1) 研究光照周期、HCO3–浓度等关键环境因子对海草植株扩繁的促进作用,完善并建立海草植株扩繁理论;2) 借鉴陆生经济植物高效扩繁技术,研发低成本的海草植株人工扩繁平台和设施;3) 研究定植时间、密植、深耕、施肥等措施对植株扩繁的影响,形成植株定植效应提升理论和技术,实现植株扩繁的陆海接力和生态培育。最终形成海草植株扩繁与定植技术体系,为我国沿岸受损海草床生态系统的规模化修复提供技术支撑。

Abe M, Yokota K, Kurashima A,. Temperature characteristics in seed germination and growth ofAscherson and Graebner from Ago Bay, Mie Prefecture, central Japan. Fisheries Science, 2009, 75(4): 921–927

Adams JB, Bate GC. The ecological implications of tolerance to salinity by(Petagna) Grande andSetchell. Botanica Marina, 1994, 37(5): 449–456

Balestri E, Cinelli F. Isolation of protoplasts from the seagrass(L.) Delile. Aquatic Botany, 1992, 43(3): 301–304

Balestri E, Lardicci C. Effects of sediment fertilization and burial ontransplants: implications for seagrass restoration under a changing climate. Restoration Ecology, 2014, 22(2): 240–247

Beer S, Eshel A, Waisel Y. Carbon metabolism in seagrasses. Journal of Experimental Botany, 1980, 31(123): 1027–1033

Berns DM. Physiological responses ofandto experimental salinity levels. Master′s Thesis of University of South Florida, 2003, 72

Biebl R, Mcroy CP. Plasmatic resistance and rate of respiration and photosynthesis ofat different salinities and temperatures. Marine Biology, 1971, 8(1): 48–56

Busch KE, Golden RR, Parham TA,. Large-scale(Eelgrass) restoration in Chesapeake Bay, Maryland, USA. Part I: A comparison of techniques and associated costs. Restoration Ecology, 2010, 18(4): 490–500

Cui CJ, Liu YL, Wang N,. Isolation and culture of protoplasts in eelgrass. Fishery Science, 2014, 33(8): 508–511 [崔翠菊, 刘延岭, 王娜, 等. 大叶藻原生质体的分离和培养. 水产科学, 2014, 33(8): 508–511]

Dawes C, Chan M, Chinn R,. Proximate composition, photosynthetic and respiratory responses of the seagrassfrom Florida. Aquatic Botany, 1987, 27(2): 195–201

Deng WH, Lü XF. Advances in studies on salt-tolerance mechanism of. Plant Physiology Journal, 2018, 54(5): 718–724 [邓文浩, 吕新芳. 大叶藻耐盐机理的研究进展. 植物生理学报, 2018, 54(5): 718–724]

Dennison WC, Alberte RS. Role of daily light period in the depth distribution of(Eelgrass). Marine Ecology Progress Series, 1985, 25(1): 51–61

Dennison WC, Orth RJ, Moore KA,. Assessing water quality with submersed aquatic vegetation. Bioscience, 1993, 43(2): 86–94

Drysdale FR, Barbour MG. Response of the marine angiospermto certain environmental variables: A preliminary study. Aquatic Botany, 1975, 1(2): 97–106

Duarte CM. Allometric scaling of seagrass form and productivity. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 1991,77(2–3): 289–300

Ferdie M, Fourqurean JW. Responses of seagrass communities to fertilization along a gradient of relative availability of nitrogen and phosphorus in a carbonate environment. Limnology and Oceanography, 2004, 49(6): 2082–2094

Fernández JA, García-Sánchez MJ, Felle HH. Physiological evidence for a proton pump and sodium exclusion mechanisms at the plasma membrane of the marine angiospermL. Journal of Experimental Botany, 1999, 50(341): 1763–1768

Gao J, Yang S. Tissue culture and rapid propagation of submerged morcorphyteL. Plant Physiology Communications, 2006, 42(2): 251–252 [高建, 杨劭. 沉水植物菹草的组织培养和快速繁殖. 植物生理学通讯, 2006, 42(2): 251–252]

Gao YP, Fang JG, Tang W,. Seagrass meadow carbon sink and amplification of the carbon sink for eelgrass bed in Sanggou Bay. Progress in Fishery Sciences, 2013, 34(1): 17–21 [高亚平, 方建光, 唐望, 等. 桑沟湾大叶藻海草床生态系统碳汇扩增力的估算. 渔业科学进展, 2013, 34(1): 17–21]

Garcia-Sanchez MJ, Jaime MP, Ramos A,. Sodium- dependent nitrate transport at the plasma membrane of leaf cells of the marine higher plantL. Plant Physiology, 2000, 122(3): 879–885

Goodman JL, Moore KA, Dennison WC. Photosynthetic responses of eelgrass (L.) to light and sediment sulfide in a shallow barrier island lagoon. Aquatic Botany, 1995, 50(1): 37–47

Han Q, Soissons LM, Liu D,. Individual and population indicators ofrespond quickly to experimental addition of sediment-nutrient and organic matter. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 2017,114(1): 201–209

Ibarra-Obando SE, Huerta-Tamayo R. Blade production ofL. during the summer-autumn period on the Pacific coast of Mexico. Aquatic Botany, 1987, 28(3): 301–315

Jiang X, Pan JH, Han HW,. Effects of substrate and water depth on distribution of sea weedsand. Journal of Dalian Ocean University. 2012, 27(2): 101–104 [江鑫, 潘金华, 韩厚伟, 等. 底质与水深对大叶藻和丛生大叶藻分布的影响. 大连海洋大学学报, 2012, 27(2): 101–104]

Jr Heck KL, Valentine JF, Pennock JR,. Effects of nutrient enrichment and grazing on shoalgrassand its epiphytes: Results of a field experiment. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 2006, 326(1): 145–156

Kahn AE, Durako MJ.seedling responses to changes in salinity and nitrogen levels. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology, 2006, 335(1): 1–12

Kaldy JE. Production ecology of the non-indigenous seagrass, dwarf eelgrass (Ascher. and Graeb.), in a Pacific Northwest Estuary, USA. Hydrobiologia, 2006, 553(1): 201–217

Kerr EA, Strother S. Effects of irrdiance, temperature and salinity on photosynthesis of. Aquatic Botany, 1985, 23(2): 177–183

Kong FN, Zhou Y, Sun PP,. Generation and analysis of expressed sequence tags from the salt-tolerant eelgrass species,. Acta Oceanologica Sinica, 2013, 32(8): 68–78

Lamb JB, Water JAJM, Bourne DG,. Seagrass ecosystems reduce exposure to bacterial pathogens of humans, fishes, and invertebrates. Science, 2017, 355(6326): 731–733

La Nafie YA, de Los Santos CB, Brun FG,. Biomechanical response of two fast- growing tropical seagrass species subjected to in situ shading and sediment fertilization. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology, 2013, 446: 186–193

Larkum AWD, Davey PA, Kuo J,. Carbon-concentrating mechanisms in seagrasses. Journal of Experimental Botany, 2017, 68(14): 3773–3784

Lee K, Park SR, Kim J. Production dynamics of the eelgrass,in two bay systems on the south coast of the Korean peninsula. Marine Biology, 2005, 147(5): 1091–1108

Lee K, Park SR, Kim YK. Effects of irradiance, temperature, and nutrients on growth dynamics of seagrasses: A review. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology, 2007, 350(1): 144–175

Lee SY, Kim JB, Lee SM. Temporal dynamics of subtidaland intertidalon the southern coast of Korea. Marine Ecology, 2006, 27(2): 133–144

Li LL, Zheng FY, Liu XQ,. Sexual reproductive characteristics ofL. in Shuangdao Bay. Chinese Journal of Ecology, 2015, 34(10): 2866–2872 [李乐乐, 郑凤英, 刘雪芹, 等. 双岛湾大叶藻的有性生殖特征. 生态学杂志, 2015, 34(10): 2866–2872]

Li XB, Liu YD. Studies on the conditions of water hyacinth tissue culture in vitro. Journal of Central China Normal University, 1997, 31(3): 332–335 [李学宝, 刘永定. 凤眼莲组织培养的研究. 华中师范大学学报, 1997, 31(3): 332–335]

Li WT, Kim JH, Park JI,. Assessing establishment success oftransplants through measurements of shoot morphology and growth. Estuarine Coastal and Shelf Science, 2010, 88(3): 377–384

Liu L, Liu SQ, Xu L,. Study on the change of nitrogen metabolism and peroxidase activity in onions during different photoperiod and vernalization. Acta Agriculture Boreali- occidentalis Sinica, 2005, 14(6): 90–95 [刘磊, 刘世琦, 许莉, 等. 光周期及春化处理对洋葱蛋白质合成代谢与POD活性的影响. 西北农业学报, 2005, 14(6): 90–95]

Liu YL, Li XJ, Cui CJ,. Study on the disinfection method for tissue culture of. Journal of Agriculture, 2013, 3(3): 54–56 [刘延岭, 李晓捷, 崔翠菊, 等. 大叶藻组织培养中外植体消毒方法的研究. 农学学报, 2013, 3(3): 54–56]

Liu YS, Guo D, Zhang PD,. Assessing establishment success and suitability analysis oftransplants using staple method in northern lagoons. Chinese Journal of Plant Ecology, 2015, 39(2): 176–183 [刘燕山, 郭栋, 张沛东, 等. 北方澙湖大叶藻植株枚订移植法的效果评估与适宜性分析. 植物生态学报, 2015, 39(2): 176–183]

Lopez Y, Royo C, Pergent G,. The seagrassas indicator of coastal water quality: Experimental intercalibration of classification systems. Ecological Indicators, 2011, 11(2): 557–563

Loughman BC, Russell RS. The absorption and utilization of phosphate by young barley plants. Journal of Experimental Botany, 1957, 8(2): 280–293

Ludewig U. Ion transport versus gas conduction: Function of AMT/Rh-type proteins. Transfusion Clinique et Biologique Journal De La Société Française De Transfusion Sanguine, 2006, 13(1): 111–116

Marbà N, Duarte CM. Scaling of ramet size and spacing in seagrasses: Implications for stand development. Aquatic Botany, 2003, 77(2): 87–98

Martins I, Neto JM, Fontes MG,. Seasonal variation in short-term survival oftransplants in a declining meadow in Portugal. Aquatic Botany, 2005, 82(2): 132–142

Masini RJ, Manning CR. The photosynthetic responses to irradianceand temperature of four meadow-forming seagrasses. Aquatic Botany, 1997, 58(1): 21–36

Mazzella L, Alberte RS. Light adaptation and the role of autotrophic epiphytes in primary production of the temperate seagrass,L. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology, 1986, 100(1–3): 165–180

Mcleod E, Chmura GL, Bouillon S,. A blueprint for blue carbon: Toward an improved understanding of the role of vegetated coastal habitats in sequestering CO2. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, 2011, 9(10): 552–560

Nejrup LB, Pedersen MF. Effects of salinity and water temperature on the ecological performance of. Aquatic Botany, 2008, 88(3): 239–246

Ochieng CA, Short FT, Walker DI. Photosynthetic and morphological responses of eelgrass (L.) to a gradient of light conditions. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology, 2010, 382(2): 117–124

Olsen JL, Rouzé P, Verhelst B,. The genome of the seagrassreveals angiosperm adaptation to the sea. Nature, 2016, 530(7590): 331–335

Palacios S, Zimmerman R. Response of eelgrassto CO2enrichment: Possible impacts of climate change and potential for remediation of coastal habitats. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 2007, 344: 1–13

Peralta G, Bouma TJ, van Soelen J,. On the use of sediment fertilization for seagrass restoration: A mesocosm study onL. Aquatic Botany, 2003, 75(2): 95–110

Qiu GL. Restorations of the intertidal seagrass beds.Beijing: China Forestry Publishing House, 2014 [邱广龙. 潮间带海草床的生态恢复. 北京: 中国林业出版社, 2014]

Ralph PJ. Photosynthetic responses of(R. Br.) Hook. f. to osmotic stress. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology, 1998a, 227(2): 203–220

Ralph PJ, Burchett MD. Photosynthetic response ofto heavy metal stress. Environmental Pollution, 1998b, 103(1): 91–101

Ren YZ, Chen YH, Ku LX,. Response to photoperiodical variation and the clone of a photoperiod-related gene in Maize.Scientia Agricultura Sinica, 2006, 39(7): 1487–1494 [任永哲, 陈彦惠, 库丽霞, 等. 玉米光周期反应及一个相关基因的克隆. 中国农业科学, 2006, 39(7): 1487–1494]

Robertson AI, Mann KH. Disturbance by ice and life-history adaptations of the seagrass. Marine Biology, 1984, 80(2): 131–141

Rubio L, García D, García-Sánchez MJ,. Direct uptake of HCO3−in the marine angiosperm(L.) Delile driven by a plasma membrane H+economy. Plant, Cell and Environment, 2017, 40(11): 2820–2830

Ruiz JM, Romero J. Effects of disturbances caused by coastal constructions on spatial structure, growth dynamics and photosynthesis of the seagrass. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 2003, 46(12): 1523–1533

Sharkey TD, Raschke K. Effect of light quality on stomatal opening in leaves ofL. Plant Physiology, 1981, 68(5): 1170–1174

Sheridan P, McMahan G, Hammerstorm K,. Factors affecting restoration ofto Galveston Bay, Texas. Restoration Ecology, 1998, 6(2): 144–158

Short F, Carruthers T, Dennison W,. Global seagrass distribution and diversity: A bioregional model. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology, 2007, 350(1–2): 3–20

Torquemada YF, Durako MJ, Lizaso JLS. Effects of salinity and possible interactions with temperature and pH on growth and photosynthesis ofEiseman. Marine Biology, 2005, 148(2): 251–260

Torrey JG. Root hormones and pant growth. Annual Review of Plant Physiology, 1976, 27(1): 435–459

Touchette BW, Burkholder JAM. Carbon and nitrogen metabolism in the seagrass,L.: Environmental control of enzymes involved in carbon allocation and nitrogen assimilation. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology, 2007, 350(1): 216–233

van Katwijk MM, Bos AR, de Jonge VN,. Guidelines for seagrass restoration: importance of habitat selection and donor population, spreading of risks, and ecosystem engineering effects. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 2009, 58(2): 179–188

van Keulen M, Paling EI, Walker CJ. Effect of planting unit size and sediment stabilization on seagrass transplants in western Australia. Restoration Ecology, 2003, 11(1): 50–55

Walker DI. Correlations between salinity and growth of the seagrass(Labill.) Sonder & Aschers. In Shark Bay, Western Australia, using a new method for measuring production rate. Aquatic Botany, 1985, 23(1): 13–26

Walker DI, McComb AJ. Seasonal variation in the production, biomass and nutrient status of(Labill.) Sonder ex Aschers. andHook.f. in Shark Bay, Western Australia. Aquatic Botany, 1988, 31(3): 259–275

Watanabe M, Nakaoka M, Mukai H. Seasonal variation in vegetative growth and production of the endemic Japanese seagrass: A comparison with sympatric. Botanica Marina, 2005, 48(4): 266–273

Waycotta M, Duarteb CM, Carruthersc TJB,. Accelerating loss of seagrasses across the globe threatens coastal ecosystems. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2009, 106(30): 12377–12381

Wilhelm C, Krámer P, Wild A. Effect of different light qualities on the ultrastructure, thylakoid membrane composition and assimilation metabolism of. Physiologia Plantarum, 2010, 64(3): 359–364

Woolley DJ, Wareing PF. The interaction between growth promoters in apical dominance. New Phytologist, 1972, 71(5): 781–793

Wu YL, Gao YP, Lü XN,Ecological contribution ofin the seagrass meadow of Sanggou Bay. Progress in Fishery Sciences, 2018, 39(6): 126–133 [吴亚林, 高亚平, 吕旭宁, 等. 桑沟湾楮岛大叶藻床区域菲律宾蛤仔的生态贡献. 渔业科学进展, 2018, 39(6): 126–133]

Xu DQ, Gao W, Ruan J. Effects of light quality on plant growth and development. Plant Physiology Journal. 2015, 51(8): 1217–1234 [许大全, 高伟, 阮军. 光质对植物生长发育的影响. 植物生理学报, 2015, 51(8): 1217–1234]

Ye CJ, Zhao KF. Advances in the study on the marine higher plant eelgrass (L.) and its adaptation. Chinese Bulletin of Botany, 2002, 19(2): 184–193 [叶春江, 赵可夫. 高等植物大叶藻研究进展及其对海洋沉水生活的适应. 植物学通报, 2002, 19(2): 184–193]

Yu H. Studies on morphological characters and tissue culture of eelgrass (L.). Master’s Thesis of Liaoning Normal University, 2008 [于函. 大叶藻形态学及组织培养的研究. 辽宁师范大学硕士研究生学位论文, 2008]

Yuan YD, Song ZC, Guo CL,. Morphological characters and microstructure of. Transactions of Oceanology and Limnology, 2010(3): 73–78 [原永党, 宋宗诚, 郭长禄, 等. 大叶藻形态特征与显微结构. 海洋湖沼通报, 2010 (3): 73–78]

Zhang Q, Liu J, Zhang P,. Effect of silt and clay percentage in sediment on the survival and growth of eelgrass: transplantation experiment in Swan Lake on the eastern coast of Shandong Peninsula, China. Aquatic Botany, 2015, 122: 15–19

Zieman JC. Seasonal variation of turtle grass,König, with reference to temperature and salinity effects. Aquatic Botany, 1975, 1: 107–123

Zimmerman RC, Hill VJ, Jinuntuya M. Experimental impacts of climate warming and ocean carbonation on eelgrass. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 2017, 566(27): 1–15

Research Advances in Shoot Propagation Theory and Planting Technique of Seagrasses

ZHANG Peidong①, ZHANG Yanhao, ZHANG Hongyu, ZHANG Xiumei

(Key Laboratory of Mariculture, Ministry of Education, Ocean University of China, Qingdao 266003)

Seagrass is a kind of higher angiosperm that originated as a terrestrial plant and over time became adapted to a marine environment. Seagrass beds have important ecological and economical value in that they provide habitats and feeding areas for diverse marine fauna, playing a key role in establishing a flourishing marine ecosystem. From 1993 to 2003, the seagrass acreage lost reached 2.6 × 106hm2. The first estimated acreages of seagrass beds were recorded in 1879, and based on historical records, it is estimated that more than 5.1 × 106hm2of seagrass beds have completely disappeared. With the severe decline of seagrass beds and the public’s recent awareness of their ecological functions, seagrass bed ecological restoration has become one of the more important coastal, environmental engineering projects. Habitat enhancement is the main method utilized in seagrass bed restoration. Currently, seagrass bed restoration is in urgent need of well-organized planning, and large-scale artificial propagations have become vital to current habitat restoration. In order to significantly increase the quantity and efficiency with which seagrass is propagated, this study was to understand the characteristics of seagrass shoot clonal propagation, and determine what techniques would allow efficient plant propagation. In order to achieve highly efficient seagrass shoot propagation, it is necessary to: 1) Promote growth and propagation of key factors; 2) Construct and implement an artificial propagation platform; and 3) Disseminate the growth and propagation planting technique. In this study, the current state of research and knowledge of shoot propagation and planting of seagrasses was reviewed, the environmental factors affecting the growth and development of seagrass shoots was summarized, and the effect of planting space, planting time, and fertilization on the seagrass shoot growth and production was discussed. In addition, the key problems existing at present were summarized. Given the advances in research and public desire to restore damaged ecosystems, there is strong potential for large-scale restoration of damaged seagrass beds along the coast of China in the future, and the summaries provided here will hopefully be a useful reference to these projects.

Clonal growth; Ecological factor; Shoot planting; Seagrass

ZHANG Peidong, E-mail: zhangpdsg@ouc.edu.cn

Q948.8

A

2095-9869(2020)04-0181-09

10.19663/j.issn2095-9869.20190506001

http://www.yykxjz.cn/

张沛东, 张彦浩, 张宏瑜, 张秀梅. 海草植株扩繁理论及其定植效应的研究进展. 渔业科学进展, 2020, 41(4): 181–189

Zhang PD, Zhang YH, Zhang HY, Zhang XM. Research advances in shoot propagation theory and planting technique of seagrasses. Progress in Fishery Sciences, 2020, 41(4): 181–189

* 国家自然科学基金项目(41576112)、中央高校基本科研业务费专项(201822021)和科技基础性工作专项(2015FY110600)共同资助 [This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (41576112), Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (201822021), and National Science and Technology Basic Work Program (2015FY110600)].

张沛东,教 授,E-mail: zhangpdsg@ouc.edu.cn

2019-05-06,

2019-08-20

(编辑 陈 严)