Geoepidemiologic variation in outcomes of primary sclerosing cholangitis

Tej I Mehta,Simcha Weissman,Brian M Fung,James H Tabibian

Tej I Mehta,Department of Medicine,University of South Dakota Sanford School of Medicine,Sioux Falls,SD 57108,United States

Simcha Weissman,Department of Medicine,Hackensack University-Palisades Medical Center,North Bergen,NJ 07047,United States

Brian M Fung,Department of Medicine,Olive View-UCLA Medical Center,Sylmar,CA 91342,United States

James H Tabibian,Department of Medicine,UCLA-Olive View Medical Center,Sylmar,CA 91342,and Health Sciences Clinical Associate Professor,David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA,Los Angeles,CA 90095,United States

Abstract

Key words:Cholangiocarcinoma;Inflammatory bowel disease;Liver transplantation;Geography;Biliary tract;Autoimmune

INTRODUCTION

Primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) is a chronic,cholestatic liver disease of unclear etiopathogenesis with a wide spectrum of presentations[1].The natural history of PSC is one that generally progresses to cirrhosis,liver failure,and death[2-5].PSC most often affects males in the fourth decade of life,though males as well as females of all ages may be affected.It is also strongly associated with inflammatory bowel disease(IBD)[6-8].Though a rare disease,PSC is the fifth leading indication for liver transplantation (LT) in the United States and a major indication in other countries[1,3-5].Moreover,no medical therapy has been shown to significantly delay PSC progression;indeed,it has been suggested that PSC treatments are one of the greatest unmet needs in hepatology[9,10].

Despite the global incidence of PSC,outcomes data are lacking from certain regions of the world.Additionally,few studies have looked at the specific subset of patients with PSC and concurrent IBD (PSC-IBD) with respect to the frequency of their concurrence and the impact on disease-related outcomes.To this end,we queried the PubMed and EMBASE databases on PSC and PSC-IBD related outcomes and abstracted the available relevant data.Based on our findings,we herein review the geoepidemiologic variation in the outcomes of PSC,focusing particularly on LT-free,overall,and post-LT survival,as well as the concurrence of PSC with IBD,and the association of PSC with hepatobiliary and other malignancies.

OUTCOMES IN PRIMARY SCLEROSING CHOLANGITIS

Geographic variations in survival

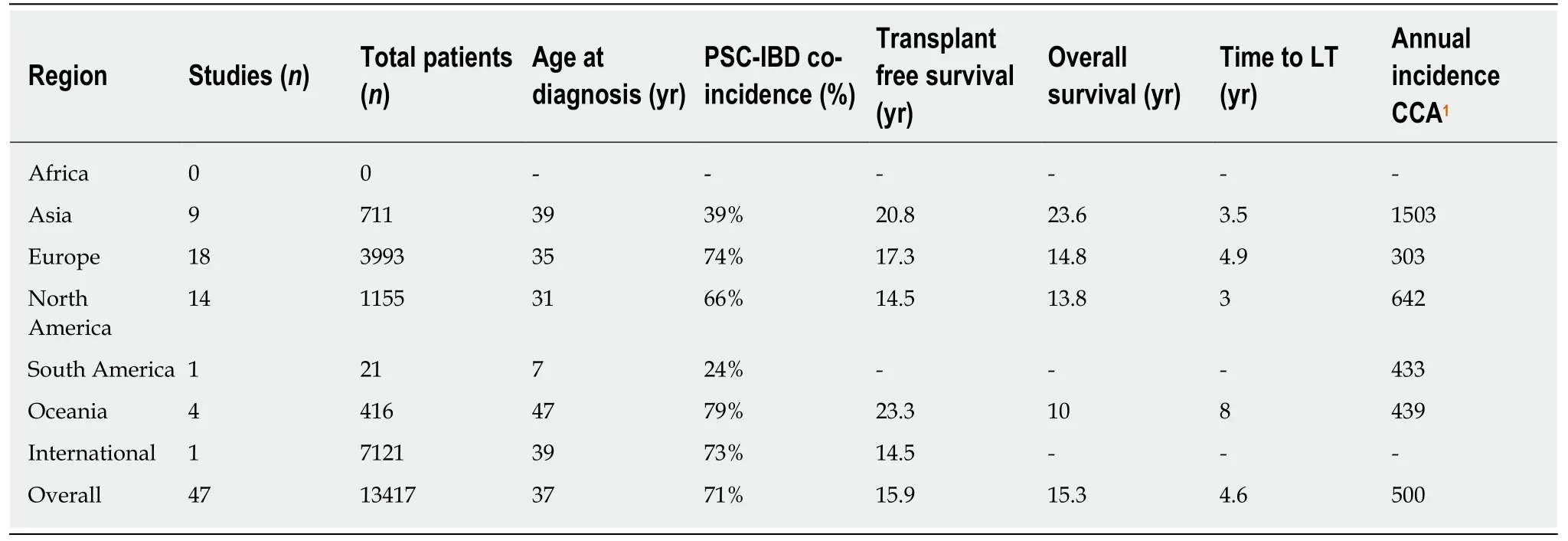

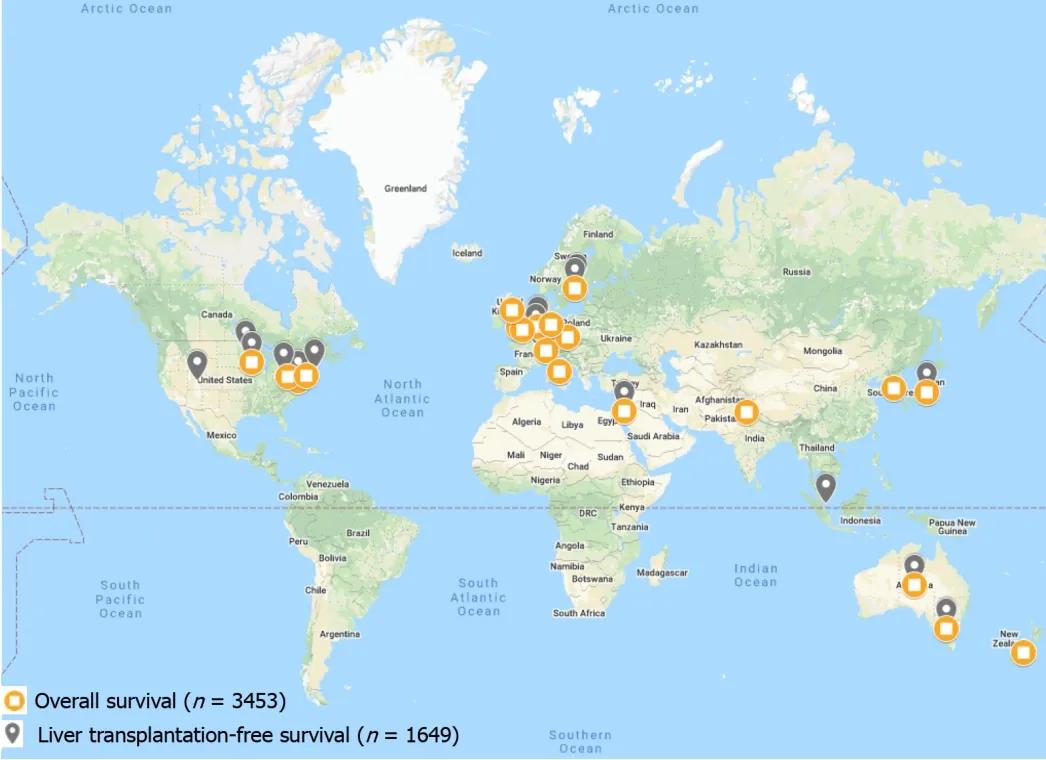

Survival in patients with PSC is highly variable with patient demographics and disease severity playing a large role in this variation.Global LT-free survival (survival free of liver-related death or LT) and global overall survival (OS) among patients with PSC has recently been reported to be 15-20 years from time of diagnosis,though significant variation exists (Table 1).Historically,European and North American studies have reported a median time from diagnosis to death or LT of 10 to 12 years[1,8,11,12].Recent studies have suggested longer survival times,though this may be due to the fact that until recently,there have only been a small number of outcomesbased studies examining survival in PSC[6,11-14].Technological advances in LT may also play a role in the metric of LT-free survival (as higher frequencies of LT and/or LT performed at younger ages can decrease LT-free survival).In Europe,Asia,and Oceania,median LT-free survival time appears to be 20 years or more[1,15,16].However,this statistic does not provide a complete picture.In a Netherlands-based study,Boonstraet al[1]reported the median LT-free survival for all patients with PSC to be 21.3 years[1].However,median LT-free survival of the subset of patients with PSC treated at LT centers was only 13.2 years[1].In a Japan-based study,Kumagaiet al[17]noted a median LT-free survival and OS of 18 years,though these patients were recruited from a LT center.Median LT-free survival and OS in some regions,such as Israel,even reach as high as 23.5 and 26.3 years,respectively[16].Indeed,survival among patients with PSC may be increasing,but major confounding factors such as availability of LTs,patient criteria for LTs,as well as competing survival risks and variable ages at disease presentation may disproportionately influence apparent LTfree survival in various regions.Furthermore,few if any studies have been performed in Central and South America,Africa,and much of Asia;thus,trends and comparisons of survival in these regions cannot be accurately performed at this time(Figure 1).

Overall,patients with PSC have a three- to four-fold increased risk of all-cause mortality compared to the general population[1,18-20].Across reported regions,the leading causes of death among patients with PSC are cholangiocarcinoma (CCA),liver failure,LT-related complications,and colorectal cancer[1,8,21-23].In Asia,liver dysfunction is reported as the most common cause of death in patients with PSC(40%-70%),whereas in Europe and North America the plurality (40%-50%) of PSCrelated deaths are due to cancer[16,17,24,25].

Variations in post-liver transplant survival

LT is the treatment of choice for patients with advanced PSC-related hepatobiliary disease.Current practice guidelines support referral for LT when patients develop a Model for End-stage Liver Disease score of 15 or greater,a Child-Pugh-Turcotte classification of C,or when LT may significantly improve quality of life,such as in the case of intractable pruritis[22,26-29].However,data regarding time to LT are often difficult to compare between populations because:(1) Studies at referral centers generally have patients with more severe disease,and thus may be more likely to receive a LT (Berkson's bias);and (2) Patients living in countries/regions with greater health care access may be more likely to receive LTs.For example,the increased availability of LT centers in Europe and North America has significantly altered clinical outcomes such that nearly 50% of patients with PSC treated in these countries receive LTs[30].In contrast,only approximately 4%-12% of patients in Asian countries receive LTs[17,31].A major reason for this is that certain countries,such as Japan,have significant shortages of brain death donors and thus rely heavily on living donor LTs[17].

Various European and American studies have reported 1,3,5 and 10-year post-LT survival rates in the 70% to 90% range;however,post-LT survival in Asia appears lower with 5 and 10 year post-LT survival rates in the range of 55% to 75%[22,31-38].Regional differences in post-LT survival may,in part,be due to overall greater clinical experience with LTs in Europe and North America or variations in patient selection criteria across regions.However,other factors may also play a role.Genetic differences,such as human leukocyte antigen profiles,have been associated with LT success rates,and the genetic underpinnings of PSC may help to explain some of the observed differences[32,39].One North American study explored the risk of LT listing among patients with PSC and identified significantly different HLA associations among various ethnic groups.In particular,European Americans and Hispanics with PSC listed for LT had similar HLA profiles,but African Americans displayed a different HLA profile[40].In addition,African Americans were more likely to have severe PSC-related disease than other ethnic groups in this study independent of socioeconomic factors,suggesting that genetics may contribute to PSC phenotype[40].Unfortunately,linkage disequilibrium patterns,associations with HLA-DRB1,HLA-B,and other non-HLA genes as well as varying nomenclature and typing methodologies across regions over time currently preclude the clinical utility of PSC genotyping[41].Of note,limited data on post-LT survival in pediatric patients with PSC are available;one North American study reported the 5-year LT- free survival among children with PSC to be 78%[42].

Geographic variations in post-transplant PSC recurrence

Approximately 20%-25% of patients with PSC experience disease recurrence post-LT,though this rate varies by cohort[43].Recurrent PSC (rPSC) carries the potential need for re-LT and increased risk of mortality.The etiology of rPSC is unknown,but various studies have attempted to identify possible risk factors for recurrent disease.Across regions,pre-LT colectomy has been associated with reduced risk of rPSC,whereas increased age,presence of IBD,increased Model for End-stage Liver Disease score,acute cellular rejection,and pre-LT CCA have been associated with increased risk of rPSC[43].Time-to-recurrence post-LT also appears to be similar across regions with a median time to recurrence of 5.1 years and a range spanning a few months to multiple decades[43].Of note,among studies examining rPSC,the median age at LT appears to be younger in Asian studies compared with the global average(approximately 33 yearsvs45 years,respectively)[32,36,43,44].However,as stated previously,most of these data come from European and North American LT centers,possibly limiting prognostication to other regions.Analyses of LT-free survival,OS,and time to LT were conducted using weighted averages of studies from each reported geographic region (Table 1).

Table1 Overall and regional primary sclerosing cholangitis clinical outcomes in terms of overall survival (measured in years) and incidence of cholangiocarcinoma

PRIMARY SCLEROSING CHOLANGITIS AND INFLAMMATORY BOWEL DISEASE

Geographic variations in PSC-IBD

Long-established associations and complex interactions exist between PSC and IBD.The PSC-IBD phenotype is distinct with outcomes different from those seen in PSC or IBD alone.Moreover,geographic variations may exist in the PSC-IBD phenotype.In particular,studies from Oceania have noted patients with PSC-IBD to be at an increased risk of death and increased risk of gastrointestinal or hepatobiliary malignancies than patients with PSC alone[45,46].In contrast,multiple studies from Asia have not identified significant differences in these outcome measures between patients with PSC-IBD and PSC alone[16,17].A study from Iran even noted favorable outcomes for patients with PSC-UC relative to those with UC alone[47].However,there are also studies from Asia suggesting worse outcomes in PSC-IBD;one study from South Korea found an increased risk of colorectal neoplasia and a trend towards increased mortality in patients with PSC-UC compared to those with UC alone[48].Studies from North America generally report worse outcomes for patients with the PSC-IBD phenotype,with most studies suggesting a significantly increased risk of neoplastic disease,rPSC,and potentially earlier onset of rPSC post-LT[49-54].Studies from Europe appear to have similar findings to that of North America;patients with PSC-IBD appear to have an increased risk of neoplastic disease,particularly colorectal dysplasia,compared to patients with either PSC or IBD alone[1,55].However,European studies generally have not identified significant survival differences between patients with PSC-IBD and PSC alone[11,55,56].

Differences concerning age at presentation of PSC and PSC-IBD appear to remain highly variable.Multiple studies from various regions have noted that patients with PSC-IBD present at an earlier age than patients with PSC alone,but there are also studies in similar regions that have not identified significant age differences[11,16,17,45,46,49].Whether this is due to IBD-related symptomatology leading to an earlier age of diagnosis and thus lead-time bias or if the PSC-IBD phenotype itself tends to present at an earlier age is unclear[57].

PSC-IBD concurrence rates appear to vary between regions.Roughly 65% of patients with PSC in Western countries have concurrent IBD,whereas only 30% of patients with PSC in East Asian countries have concurrent IBD[8,17,58,59].Interestingly,among patients with PSC-IBD in Europe and East Asian countries,the concurrence of PSC-UC was similar at approximately 80%[8,17,58,59].However,studies from Central Asia and the Middle East have more variable results.Generally,PSC-IBD concurrence rates in these regions are reported as similar to those in Europe,but PSC-UC concurrence rates are much lower,often under 60%[16,60,61].Lastly,some regions,such as central and southern Europe,Alaska,and northern Canada have identified either very low or even no concurrence of PSC with IBD[62-64].

Figure1 Locations of all studies reporting liver transplantation-free and overall survival in primary sclerosing cholangitis.

PRIMARY SCLEROSING CHOLANGITIS AND NEOPLASIA

Geographic associations with cholangiocarcinoma

PSC is a major risk factor for the development of CCA.The risk of CCA among patients with PSC is roughly 400 times that of the general population[1].The global annual incidence of CCA is approximately 500 per 100000 patients with PSC,or 0.5%annually (Table 1).

The annual incidence of CCA among adult and pediatric patients with PSC is roughly 7%-9% across populations,though estimates in North America vary greatly,with reported incidences as low as 4% and as high as 20%[1,11,42,65-67].The highest annual incidence of CCA is in Asia,with incidences as high as three times the global average;the reason for this elevated incidence is unknown (Table 1)[16,35,60,68,69].Interestingly,the highest non-PSC related rates of CCA are also seen in Asia,suggesting another variable (e.g.,parasitic infections and chronic viral hepatitis) may be playing a role in the high rate of CCA[70].

Data regarding duration of PSC and risk of CCA are variable,with several studies suggesting PSC increases the risk of CCA over time while other studies have not found the same association[1,65].This may be due to the fact that the presence of CCA in patients with PSC is often occult (with at least 10% of patients with PSC having“silent” CCA for significant lengths of time),thus the true time to development of carcinoma is unclear[71].Interestingly,both duration of IBD among PSC-IBD patients and colorectal neoplasia (CRN) among PSC-UC patients increase the risk of CCA development[72].

Geographic associations with colorectal neoplasia

IBD confers an increased risk of CRN and PSC-IBD further increases the risk of CRN above that of IBD alone[55].Of note,some studies have reported an increased risk of CRN among PSC-UC patients compared to UC patients but not among PSC-IBD patients relative to IBD patients,implying a specific disease interaction between PSC and UC[72-75].

While regional differences in PSC-IBD associated CRN are difficult to ascertain,it is known that post-LT colorectal neoplasia is of particular concern in patients with PSC and PSC-IBD[22].Among post-LT PSC-IBD patients,the risk of CRN rises by approximately 1% per year post-LT[22,76].As such,it is possible that rates of CRN among PSC-IBD patients may be greater in European and North American countries owing to the increased frequency of LT in these regions,though there is little evidence to support this directly.Annual endoscopic monitoring is considered standard of care among PSC-IBD patients[77].

LIMITATIONS

Geographic reporting of PSC-related outcomes is heterogenous,with the majority of studies coming from Europe and North America,a limited number of studies from Asia and Oceania,and very few studies from South America and Africa,hence summary estimates were not amenable to meta-analysis.Moreover,the reporting of results differs even within similar regions,making comparisons challenging.For example,within one region,one study may report LT-free survival while another study may report OS,limiting the ability to make comparisons.Additionally,PSC case identification,outcomes,and other factors may have changed over time.Therefore,when comparing studies from one region to another we may be comparing them not only based on where the studies took place,but when they took place,potentially confounding results.Lastly,our search was limited to studies available in English,which may have left out studies from non-English speaking regions.

CONCLUSION

Studies on global PSC-related outcomes have increased over the years allowing for novel analyses of regional differences.Causes of PSC-related death vary globally,with liver dysfunction being the primary cause of PSC-related death in Asia,and cancer being the primary cause in both Europe and North America.Although notably,there is a significantly greater rate of CCA in East Asia than the rest of the world.Interestingly,PSC-IBD concurrence rates vary across regions,yet the proportions of PSC-IBD subtypes are largely consistent across regions.Likewise,PSC-IBD related outcomes appear largely consistent across regions.As most studies of PSC have been conducted in the United States and Western European countries,with a paucity of data from other regions,the need for large population-based studies in underreported regions is imperative to better understand global and regional PSC-related outcomes.

World Journal of Hepatology2020年4期

World Journal of Hepatology2020年4期

- World Journal of Hepatology的其它文章

- Liver injury induced by paracetamol and challenges associated with intentional and unintentional use

- Interleukin-6-174G/C polymorphism is associated with a decreased risk of type 2 diabetes in patients with chronic hepatitis C virus

- Comparison of four non-alcoholic fatty liver disease detection scores in a Caucasian population

- Combined endovascular-surgical treatment for complex congenital intrahepatic arterioportal fistula:A case report and review of the literature

- Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor of the liver:A case report and review of literature