乌镇之于茅盾,不止是子夜

陈富强

我能够想象,在老宅写作的先生,疲惫了,就出门去街上走走,或者,就去拱桥下的茶馆喝上一杯桐乡菊花茶。

我接触到的第一部长篇小说《子夜》的版本,是多年之前人民文学出版社出版的,封面淡蓝色,美术体的书名,既高雅,又有无限辽远的空间感。我差不多只用了一整夜的时间就读完了它。我觉得,中国的长篇小说,大约就是这个样子的。其时,《红楼梦》正打算重印,《包法利夫人》也在出版社重印的计划里。而《子夜》率先在我眼前打开一扇窗,让我看到茅盾先生笔下的文学世界竟如此盎然。于是,我一直有一个愿望,想去乌镇,在乌镇待上一晚,在子夜时分,去街上走个来回。

一

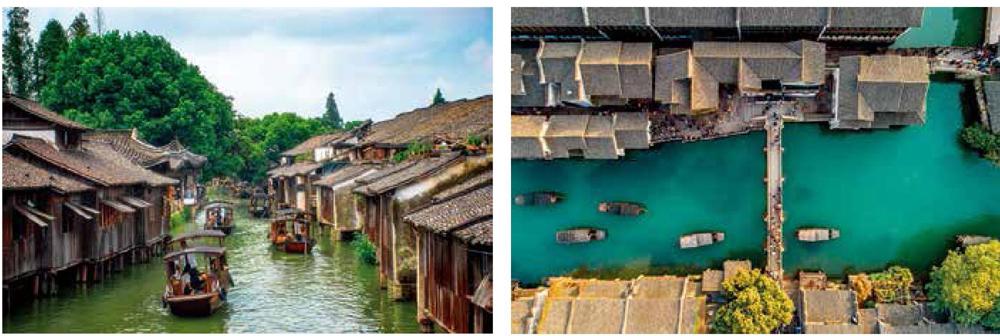

在江南,乌,通常是指一种接近于黑的颜色。因此,乌镇的来历,也与所处地域的地理特征有关。由于乌镇地处河网密布的冲积平原,淤积的泥土呈褐色,且肥沃。类似隆起于平原旷野的地方,也称作“墩”。乌镇最早的名字中,有烏墩之称。

类似乌镇这样的小镇,在江南可以列出一长串,它们仿佛一颗颗珍珠,散落在广袤的原野上,在漫长的时光里熠熠闪光。只不过,乌镇因为茅盾先生,多出一些人文气息,加上后人慧眼,使乌镇在江南古镇中声名远播,俨然是江南小镇的一张名片。如果追溯乌镇的历史,我们会发现,在所有相关的文字记载中,茅盾先生的创作背景里,乌镇的影子随处可见。

乌镇最初为人所识,是东栅。那里也是茅盾先生故居所在地。狭窄的观前街17号,保存完好的老房子为四开间两进,是一幢层木结构楼房,坐北朝南,总面积约450平方米。故居分东西两个单元,据说是茅盾的曾祖父分两次购买的。看得出来,茅盾的曾祖父在当地也算一个有脸面的人物,并且颇有一些积蓄。这些老房子保存完好,这既得益于当年茅盾的修缮,也有后人保护的功绩。其中的三间书斋,原先是平房,后来茅盾用他的稿费予以翻建。关于这笔稿费,最有意思的一个传说,是用去了先生半部《子夜》的稿费。对于这个在文坛和民间流传甚广的故事,是真是假我无从考证,但这三间书斋却因此而显出不少书香。茅盾在这里写作,《多角关系》据说就是在这里写成的。我能够想象,在老宅写作的先生,疲惫了,就出门去街上走走,或者,就去拱桥下的茶馆喝上一杯桐乡菊花茶。

茅盾在《我走过的道路》一文中曾经写到过这家茶馆:“祖父的生活,很有规律,每天上午,或到本地绅士和富商常去的访卢阁饮茶,或到西园听拍曲。”文中的访卢阁其实就是我们现在见到的这家茶馆。正对着茶馆的是一座石拱桥,放眼望去,一条小河的两岸皆为古建筑群,这里很明显地体现着乌镇的风情。那些房屋的整修风格,与乌镇的格调相吻合,河水虽然没有从前那样的清澈,但也能映出岸上房屋的倒影来。风吹过,水中的房屋就摇晃起来,摇摇欲坠的样子。我没有时间去茶馆喝一碗茶了,但我能想象得到,坐在访卢阁上,临窗而望,浓郁的水乡景色尽收眼底的那份惬意。如果是在暮色苍茫的时刻,两岸屋子里的灯光亮起来,倒映在河里,那又是另外一种让人心醉的感觉。

故居书斋外面有一个天井,不大,种满了绿色植物,一棵棕榈树还是茅盾当年翻建书斋时种下的,屈指算来,已逾八十年。我相信先生曾经在这儿驻足,曾经在这儿漫步,也曾经在这儿思考。1934年的春天,在这个天井里可以看到先生的身影,他出门向东,沿着坚硬的石板路走去,他要去看香市。乌镇的香市类似于江南其他古镇的庙会,茅盾曾经在散文《香市》里描述过香市的盛况:香市中主要的节目无非是“吃”和“玩”。临时的茶棚,戏法场,弄缸弄甏,走绳索,三上吊的武艺班,老虎、矮子,提线戏,髦儿戏,西洋镜……将神庙前五六十亩地的大广场挤得满满的。

香市的时间是在清明前后,我去的不是时候,所以大部分的香市风俗都不能看到,但在神庙前的广场上却依旧可看戏台上的演出,还可看皮影戏。高高的戏台上,演员演得专心,锣鼓也敲得地道,看戏的却不多,廖廖几个观众,远远地,听古装的演员唱《李三娘》。我听不懂一句台词,却能够感受到香市的一些味道。皮影戏在室内演,一块白布作为前景,后面有灯光照着,一阵铿锵的鼓声响过之后,皮影戏就开场了。我看到的似乎是武松打虎,鼓点十分激烈,打斗自然也不例外。我看了个头,就跑到后面去。只见双手舞动武松和老虎的是一个白发老者,随着鼓点,他的双手灵巧地在布景上移动着,左手老虎,右手武松。虎啸声则是由坐在边上的一名乐手用一件比锁呐还要长的乐器吹出来的,很雄浑,酷似老虎的长啸。另外还有两人负责敲锣。这段皮影戏的节奏很快,可能是剧情决定了戏的节奏,我还没有看出个门道来,布景后面的灯就熄灭了,这表示一出戏已经演完。走出剧场,很有些恋恋不舍。皮影戏在电影、电视和书本上看到过,真正领略却还是第一回。

二

结木为栅。栅在乌镇,其实有村庄的界限之意。有东栅,就有西栅。乌镇六千年的历史,在东栅能够找到沧桑的痕迹。而西栅,与东栅毗邻,是对原有村庄的改建。依旧是粉墙黛瓦、枕河人家。作为世界互联网大会永久会址,这里的草木建筑、小桥流水,就显出更多互联的气息,无线网络无缝覆盖。那些影响世界互联网经济走向的大人物们,在这座小镇里品尝一碗桐乡的羊肉面,也能成为一条不可多得的新闻。

茅盾先生的纪念馆和陵园建在西栅。其建筑依然延续浓郁的江南风格,但更显庄严肃穆。青砖筑成的高大墙壁,就是一面历史和文学的镜子。我戴上耳机,聆听先生的原音重现。先生写给胡耀邦的书信片断,被镌刻在纪念堂正面墙上。先生手写此信的时间是1981年,这也是他捐赠25万元人民币创议设立茅盾文学奖的年份。

《子夜》的手稿被陈列在玻璃柜中。我俯下身子,弯下腰,看到茅盾先生的手迹,那么娟秀而漂亮的字体,这样好看的小说手稿,再也不会有。

而陵园内,先生的简介,被刻在一本翻开的花岗岩书页上。先生半身雕像,目光平视前方。我顺着先生的视线,看到的是一位文学巨匠眼中无垠的天空。严家炎在《中国现代小说流派史》中称:“由茅盾开创的社会剖析小说流派,通过生活横断面再现社会,是一个革命现实主义的流派,甚至影响了后来写作的《李自成》《上海的早晨》等作品的一些作家。”这段评价恰如其分,道出茅盾先生的创作对于中国文学的影响。同样的评价,还出现在郁达夫笔下:“茅盾是早就从事写作的人。唯其阅世深了,所以每不忘社会,他的观察的周到,分析的清楚,是现代散文中最有实用的一种写法……中国若要社会进步,若要使文章和实际生活发生关系,则像茅盾那样的散文作家,多一个好一个……”

黃昏的乌镇,是一天中最美不可言的,喧嚷是没有的,却有我喜欢的宁静与寂寥。渐渐入夜,我坐在窗下,望着河水悄然流过眼前,仿佛将乌镇的从前流过来,又淌过去。《子夜》里的人物,一个个依稀从窗外走过,又隐入夜色,他们无声无息的模样,就是乌镇的子夜了。

现在,茅盾先生的创作,继续影响着一代又一代以汉语写作的作家。每位中国当代小说家,都以获得茅盾文学奖为荣。他是一座现代文学高峰,是中国新文化运动的先驱者之一。在中国现代文学史上,他与鲁迅、巴金等文学大师齐名。作为一名写作爱好者,我数次来到乌镇,向茅盾先生致意。我最初的文学素养,很大程度上来自茅盾,比如,从《春蚕》到《子夜》。

在中国汉字当中,乌,也有乌托邦之意。然而,乌镇却如此真切地存在,并且以六千年的风雅,书写着互联网世界。同样出生在乌镇的作家木心在临终前曾说过:“风啊,水啊,一顶桥。”说的恰好是乌镇。这里的每一条河流,都与京杭大运河相连,流水带走的,不止是风雨,还有辽阔的江南。

(本文图片来自视觉中国)

The first novel I read is , the masterpiece of Mao Dun (1896-1981), who is considered a milestone and a revolutionist in Chinas modern literature. That was many years ago, and I still remember the pale blue color of the cover with the elegantly printed title on it. It took me a whole night to read the long story. My encounter with Mao Duns magnum opus was long before other literary masterpieces such as and were reprinted and made available to the public in China after the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976). The novel opened up the mystical world of Wuzhen, making me dream of spending a night there and taking a midnight walk in the town, just as the writer did many, many times.

The literal reference of “乌”, pronounced “wu” in Chinese, in most of the Jiangnan regions of China, is the color that borders black. It makes a lot of sense in the name “Wuzhen”, suggestive of the pitchy color of the fertile soil of the alluvial plain where the “water town” is sited.

Wuzhen is one of the brightest pearls in the long list of “water towns” across Chinas Jiangnan, and is one of the most culturally distinct, thanks to such big names as Mao Dun, who used his beloved hometown as the most important backdrop of all his works.

The fame of Wuzhen first came from Dongzha, where the ancestral home of Mao Dun, located on Guanqian Street, is drawing cultural buffs throughout the year. The 450-square-meter estate is a well-conserved wood structure divided into the east and west wings, allegedly purchased by two installments by the great grandfather of Mao Dun. The rebuilding of the three studies inside the house allegedly cost more than half of the royalty the writer earned from the publishing of . It is believed that Mao Dun also wrote his in one of the studies. I can picture the scene of the mans leisurely walk or tea break at his favorite teahouse near the stone bridge after a tiring writing session in the old house.

In , the writer mentioned his favorite teahouse: “The day of my grandfather started with a cup of morning tea at Fang Lu Ge teahouse, or at the West Park, when his musical mood set in…”

The lovely view of ancient architectural complexes and beautiful reflections of the houses in the river in front of the Fang Lu Ge teahouse must have inspired the writer a million times. We had no time for the tea when we were there, but I can imagine how the writer must have felt refreshed when taking in the mellowness of the sunset landscape of the water town to his hearts content.

The patio outside the study teems with plants. The palm tree planted by the writer right after the completion of the construction of the studies has thrived for more than 80 years.

On a sunny day in the springtime of 1934, the writer was out for a walk to see the towns temple fair, held once a year around the Qingming Festival. The hilarious spectacle of street performers, vendors and ne'er-do-wells interacting with each other was later recorded vividly in one of his essays, titled .

During my promenade in the town, I chanced upon a leather-silhouette show of at the square used as the venue for the temple fair. I sneaked into the backstage to find out more about the stunts of the performers. Most of the scenes on the stage were manipulated by an old man using his two hands; and the roaring of the “tiger” was made by an instrumentalist who used something like a “suona” (a woodwind instrument). The tempo and the tension created by such a tiny team impressed me.

The towns Dongzha area is the crystallization of the 6,000-year vicissitude of the town. The natural villages on the west side of the town have been rebuilt into a hot tourist area named as “Xizha” and serving as the permanent venue of the World Internet Conference (WIC).

Xizha also hosts the tomb of Mao Dun and the Mao Dun Memorial Museum, where visitors can admire the graceful handwriting of the writer from the manuscripts of and explore the mans brilliant spirituality in a wonderful collection of exhibits.

In 1981, Mao Dun Literature Award was launched, using the 250,000-yuan donation from the writer. In the eye of Yan Jiayan, a famous writer, Mao Dun created a new literature genre that influenced many writers including Yao Xueyin who wrote and Zhou Erfu who wrote , bestsellers of decades ago. Yu Dafu also spoke highly of the strong realism in Mao Duns works: “He is an observer of the society, and his writing comes from the reality of life…”

Wuzhen is also the birthplace, and the resting place, of renowned essayist Mu Xin, another cultural icon of the town. “The wind, the water, and a bridge…” The writer reminisced, before leaving the world.