“葡萄酒还是啤酒?”

司马勤

这段日子,我心里一直想着要喝酒。这是长期待在家中自我隔离的附属症状。还有一种可能是,就算世界各大歌剧院还没有因为疫情关门之前,这些年来家里的酒吧推车(bar cart)一直停在那个从地面到顶棚都摆满歌剧录音的架子旁。你也许会把这种念头归咎于社会心理学的接近原则(proximity principle),但我开始考虑认真地探讨下美酒与歌剧这两者之间的关系。

前两个月,我在专栏里曾半开玩笑地说过,当歌剧院重开大门举行演出,如果从指挥的第一拍起拍直至终场落幕之间,观众随时可以品尝美酒,那该多好。当然,我不是怂恿歌剧迷变酒鬼。我只是希望观众把目光聚焦于舞台上演员所喝的酒类。他们怎样喝酒、在哪里喝酒,尤其是在台上喝哪种酒,都可以让我们更透彻地了解歌剧中的人物与剧情,远比文字更为深刻。你只要随便翻开欧内斯特·海明威(Ernest Hemingway)或斯科特·菲茨杰拉德(Scott Fitzgerald)的著作——或者伊夫林·沃(Evelyn Waugh)、又或金斯利·艾米斯(Kingsley Amis)(我还可以列出更多更多的名字……)——你就会明白我的意思。

其实,这一目标也不必定得太高。就拿通俗小说(genre fiction)中的几位人物为例:伊恩·弗莱明(Ian Fleming)笔下的英国间谍“007”詹姆斯·邦德(James Bond),与雷蒙·钱德勒(Raymond Chandler)系列小说中的美国私家侦探菲利普·马洛(Philip Marlowe)。就算你熟知这些人物最钟爱的鸡尾酒,我也不会给你加分:马洛让琴蕾酒(gimlet,又名螺丝起子)发扬光大(“一半琴酒,一半玫瑰牌青柠檬汁,不加其他”);邦德令马丁尼(martini)风靡一时(“伏特加……摇匀,不要搅拌”)。尽管今天的调酒师对于以上两个传统的配方都不以为然,但是这两种鸡尾酒却多多少少显露了顾客的心境或背景。

钱德勒描述的这款鸡尾酒像是为12岁孩子口味而设,而不是为了成人顾客。马洛当年的琴酒可能比不上今天蒸餾三次之后的高质量品种吧。邦德较喜欢“摇匀,不要搅拌”的调酒方法,让冰块会融化得更快,所以他的马丁尼比常见的要冰得多,酒精度也稀释不少(因此他执行任务时也不会醉醺醺)。选择伏特加却令人费解……也许连他也找不到好品质的烈酒。我脑海里更浮现这个疑问:为什么冷战时期英国政府鼎鼎大名的“铁金刚”会喜欢敌国最标志性的烈酒,而不选英国引以为傲的琴酒呢?邦德真是一个充满神秘的人物。

对不起,我又偏题了。在歌剧范畴里,鸡尾酒——或者任何烈酒——出现的机会比较罕见。歌剧艺术大多追溯至意大利与德国的文化根源,所以常见的酒类是葡萄酒与啤酒。但是,即便在这些范围内,可能参考的不同案例也很广泛。

我们也有很多方法,把“赏酒”与“ 赏歌剧”结合起来。我可以联想到朋友在家中一边看歌剧视频,一边有创意地创造出崭新的行酒规则:每当剧中人提到喝酒,观看者也需呷上一口;如果歌剧的某场景发生在酒馆内,就要大口喝;涉及喝酒的咏叹调或合唱曲一出现,大家就要一起干上一杯。那些志同道合、拥护“裤子喝醉了”(kalsarik?nnit,还记得我曾提到的那个待在家里、只穿内裤、喝得烂醉的芬兰传统)的朋友或已定出了一套独家“赏酒赏歌剧”的规则了。

今天,正因我坐在家中的歌剧唱片架子与酒吧车之间,让我们一起参考“赏酒赏歌剧”的几个亮点,看看不同角色的杯中物带给我们什么深入见解。

“哎,酒保!”——威尔第《法尔斯塔夫》(1893)

莎士比亚笔下的约翰·法尔斯塔夫爵士是舞台上首屈一指的品酒权威。这位出身贵族但品行卑劣的武士毕生追寻多种不良嗜好、挥霍无度。这威尔第最后一部的歌剧一开幕,法尔斯塔夫就已经在喝酒。到了第三幕,约翰爵士第一句就埋怨“这个坑蒙拐骗的世界”;到了咏叹调的尾声,他的心情明显好得多,因为有酒下肚了,“心脏里每一细胞都震动,颤音般的疯狂震撼着欢乐的地球”。就在这一刻,你真想跟酒保说:“他点了什么,我也要。”可想要研究他当时喝了什么这个细节就复杂了,我们要回溯莎士比亚的文本。在《温莎的风流娘儿们》(The Merry Wives of Windsor)中,法尔斯塔夫提及过加了丁香与草药的蜂蜜酒(metheglin)。但是,他平常喝的萨克酒(sack),是干雪利酒(dry sherry)的前身,酒精度高于葡萄酒,质感与口感跟中国黄酒差不多(法尔斯塔夫更吩咐酒保要把酒加热)。我要郑重声明,法尔斯塔夫没有喝过啤酒,即便现在起码有五个美国啤酒厂的产品用上了法尔斯塔夫的肖像或名字作为宣传伎俩。

“葡萄酒还是啤酒?”——古诺《浮士德》(1859)

这个重要议题出现在《浮士德》第二幕的开端。一群学生、士兵与居民兴高采烈,异口同声地唱“酒鬼什么都喝”。(很有趣,1979年百代唱片录音的德语剧本翻译,却把歌词译为“葡萄酒与啤酒”,连问号都删掉。)以我刚刚提出的喝酒游戏规则来说,这一段的胜利之声压倒全场。以喝酒为主题的大合唱重复了几遍,酒馆这个公众聚集的地方也推动戏剧发展。从历史角度来看,酒馆是平常互不相干的社会群体的共用空间,在故事里营造出享乐与冒险这两条线索。士兵准备上战场,玛格丽特(Marguerite)首次亮相,而梅菲斯特(Méphistophélès)刻意种下祸根,把自己酒窖的酒酿拿出来,令众人喝个大醉。到了最后,美酒爆出火焰,令我怀疑魔鬼收藏的酿酒质量是高是低。

“一只老鼠在厨房”——柏辽兹《浮士德的惩罚》(1846)

又是一位法国作曲家,把歌德最富德国色彩的文本编成歌剧。《浮士德的惩罚》在巴黎喜歌剧院首演后的多年里长期被忽略,到了最近才成为保留剧目,主要归功于现代舞台技术(尤其是高像素投影)凸显了歌剧的奇幻效果。柏辽兹与古诺节录的故事情节有不少重叠——在酒馆那一场,更安排了一个醉醺醺的学生领唱,描述老鼠在厨房寻欢作乐,最后吃错毒药而死的咏叹调——这段是一个巧妙的源自歌德原著的戏剧工具。在古老的民间传说里,浮士德在乌烟瘴气的酒馆里开启他沦落之途——说真的,除了酒馆,还能在哪里遇得上魔鬼?——歌德的原著中的酒馆,是莱比锡名副其实的地标(1498年已经开业的奥尔巴赫酒窖,Auerbachs Cellar)。歌德特意增添这点喜剧性,让本来污秽的酒馆变得更有生气。他的处理手法也影响了后世浮士德故事的定调。

“讓我们高举起欢乐的酒杯”——威尔第《茶花女》(1853)

毫无疑问,这是歌剧世界里的头号祝酒歌,捕捉到常住巴黎最有名的交际花与她那布尔乔亚敬慕者初相识的浪漫时刻。我们大多数人都称这首歌为“祝酒歌”(Brindisi,意大利语“祝酒歌”,源自德语祝酒词“我献给你”[ich] bringe dirs)。当薇奥莱塔跟客人寒暄过后走开几步,阿尔弗莱多带领各位宾客高歌一曲,祝酒词就是“让我们高举起欢乐的酒杯”,从而吸引到薇奥莱塔那“无法抗拒的目光”。茶花女漠视阿尔弗莱多的奉承,鼓励宾客们“享受生命,因为爱的欢乐短暂易逝”。到头来,薇奥莱塔被迷住,可惜她跟阿尔弗莱多的爱情确实短暂易逝。虽然歌词字面包含言外之意,但威尔第如泡腾片般的音乐让我可以肯定,沙龙的客人的酒杯里盛载着香槟。

“干了这杯气泡酒”——马斯卡尼《乡村骑士》(1889)

很明显,我们都知道马斯卡尼歌剧里的村民在喝什么,因为“气泡酒”出现在曲目题目中。但我们要弄清楚:威尔第创作了众所周知的“祝酒歌”;马斯卡尼只写出了“一首祝酒歌”,但这位年轻作曲家毕生第一部独幕歌剧却把现实主义推进舞台。很多乐评人都察觉到歌剧叙事手法的变化——我最喜欢的描述是这样:现实主义把上等人家族里的奸淫、诱惑、杀戮与自杀转移至普通人生活中发生的奸淫、诱惑、杀戮与自杀——你也听得出祝酒歌风格上的差别。参军回来的图里杜(Torridu)适逢复活节,跟村民一起干杯。图里杜情人的丈夫到来,拒绝与他共饮,两人相约决斗。最后悲剧收场。

“我们来个豪华晚宴,要他们醉醺醺”——莫扎特《唐乔瓦尼》(1787)

编剧达·蓬特的剧本从没有指定唐乔瓦尼最沉醉什么,但导演彼得·瑟勒斯(Peter Sellars)曾要求男主角在台上演绎自己打了毒品针——但是大家都明白,自然界里是没有真空的。唐乔瓦尼在第二幕唱出颂赞美酒、女人与歌舞的咏叹调,一早就被称为“香槟咏叹调”,莫扎特的音乐就像冒着气泡的美酒,更带有一点轻佻。整首咏叹调只有90秒时长,但角色的本质性格却表露无遗,绝对是歌剧历史的里程碑。

“酒神万岁”——莫扎特《后宫诱逃》(1782)

从放荡不羁的唐乔瓦尼到滴酒不沾的奥斯明(Osmin),莫扎特笔下的人物涵盖两极。严格上来说,《后宫诱逃》是莫扎特首部获皇室委约的舞台作品(包含对白,德语演出),利用纯音乐呈现剧情的段落不算多,但作曲家仍成功地挑战了当年常规的极限——最显著的一点是,他把土耳其风格的一切都借了过来。为了从土耳其国王帕夏(Pasha)的总管奥斯明手上救回未婚妻布隆德(Blonde),佩德里洛(Padrillo)拟出计划,慢慢灌醉奥斯明——虽然这位总管是个回教徒。奥斯明破坏了真主的戒条,甚至赞叹“酒神是个好家伙”,险些改变信仰追随罗马酒神,但终于醉倒昏迷。这是一首旖旎的歌曲,别忘了作曲家是如假包换的异教徒。

“快点,快点,快点,路德老板”——奥芬巴赫《霍夫曼的故事》(1881)

很多人都抱着怀疑,恩斯特·特奥多尔·威廉·霍夫曼(E.T.A. Hoffmann)是一位酗酒的作家,还是舞文弄墨的酒徒。奥芬巴赫的首部(也是唯一一部)歌剧两者兼并,一开幕就带我们到访路德酒馆。在那里,烈酒与葡萄酒的灵魂都自荐是作家的缪斯(这当然是被润饰的浪漫化版本,霍夫曼只活到46岁,元凶就是他的那些“缪斯”)。确实,过了几分钟,当合唱团介入的时候,酒精饮品很明显为故事情节添上动力。剩下来的问题很简单:葡萄酒还是啤酒?作曲家故意不加选择——只激励大家“把酒杯盛满,直到天亮”——做法恰当,因为作曲家在德国出生时的名字是雅各布·埃伯斯特(Jakob Eberscht),移居法国后,展开音乐生涯所用的名字是雅克·奥芬巴赫。

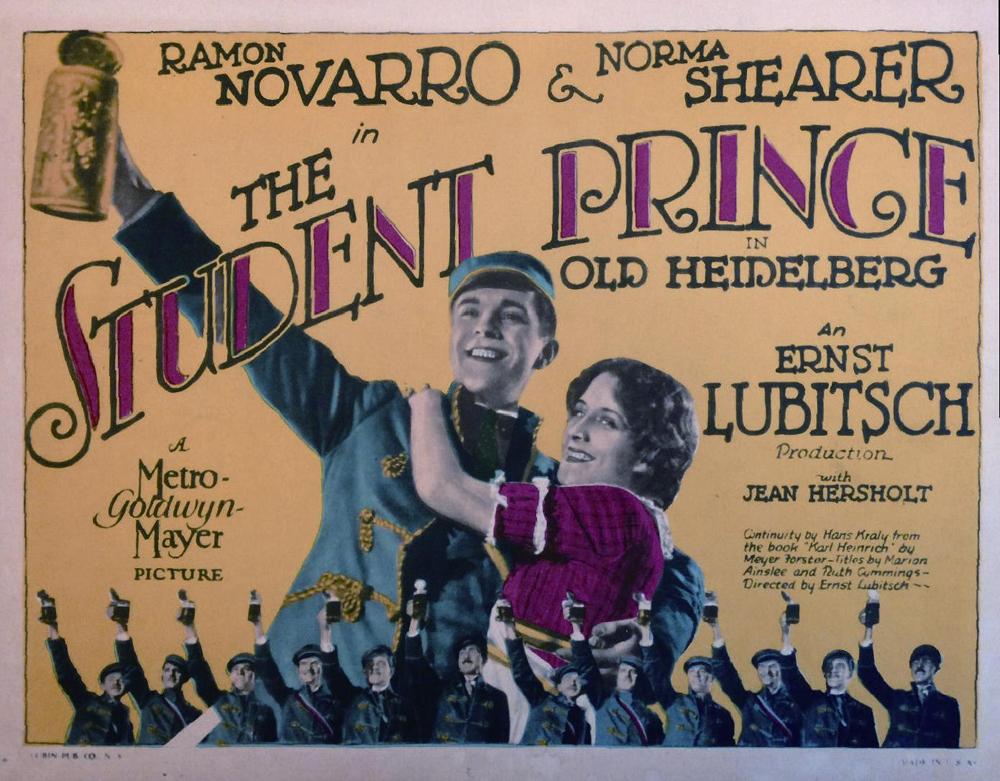

“喝!喝!喝!”——龙伯格《学生王子》(1924)

虽然奥芬巴赫在歌剧范畴的传承不算很重要,但对于轻歌剧的发展——延伸至音乐剧——却举足轻重。要是我们比较一下奥芬巴赫与龙伯格的合唱曲,我们就看得出歌剧与轻歌剧风格上的很大区别。《霍夫曼》的合唱曲里,音乐几乎没有停顿,说明情节甚至推动故事;《学生王子》[桃乐丝·唐纳利(Dorothy Donnelly)的剧本与歌词]大致把德语话剧《老海德伯格》(Old Heidelberg)移植至美国舞台,增添的歌曲对于故事发展没有很大的影响。尽管这样说,《学生王子》依旧是20世纪20年代百老汇最长寿的剧目,吸引观众的歌曲非“喝!喝!喝!”莫属——为什么会出现这个状况?因为该剧上演时,正是美国的禁酒令年代,无论酿酒或卖酒都违法。

“啤酒是天赐的礼物”——斯美塔那《被出卖的新娘》(1866)

大多数歌剧都偏袒葡萄酒——虽然奥芬巴赫与龙伯格的舞台制作里都找得到啤酒,那些歌剧还是比较中立。我终于找来一位立场清晰的作曲家。斯美塔那的父亲是酿啤酒的商人,在《被出卖的新娘》第二幕的开场,村民齐声高歌地唱道:“啤酒是天赐的礼物”。虽然这部歌剧的首演并不成功——第一版包含很多对白,观众反应冷淡——斯美塔那修改后的版本把对白删掉,音乐配合捷克语调的自然节奏与脉搏一气呵成。当剧中人争执究竟爱情还是金钱要比啤酒更重要,村民完全不理他们,继续畅饮啤酒——印证了这个以啤酒为傲的文化的真实性。

Ive been thinking a lot about drinking lately. Being quarantined does that. It probably doesnt help that, even before opera houses around the world closed their doors, my bar cart was sitting beside a floor-to-ceiling shelf of opera recordings. Blame it on the proximity principle, but Ive started pondering relationships between the two.

This is not to endorse the idea—hinted halfseriously a couple of months ago—that once opera houses open again that alcohol should be available from downbeat to curtain call. Rather, its time for audiences to pay more attention to what the characters on stage are quaffing. How, where and especially what someone is drinking often reveals more than words alone can describe. Just page through any book by Ernest Hemingway or Scott Fitzgerald—or Evelyn Waugh or Kingsley Amis (I could go on…)—and youll see what I mean.

You dont even have to aim that high. Start with a couple of characters from middlebrow genre fiction—say, Ian Flemings British spy James Bond and Raymond Chandlers American private detective Philip Marlowe. No bonus points for naming their respective drinks: Marlowe did for the gimlet (“half gin and half Roses Lime Juice and nothing else”) what Bond did for the martini (“vodka…shaken, not stirred”). Neither recipe would pass the scrutiny of a grown-up bartender, but they do reveal a lot about the customer.

Chandlers overly sweet proportions show that perhaps Marlowes gin was not of triple-distilled quality. Bonds preference for “shaken, not stirred”meant that his ice melted faster, so his drinks were(1) much colder and (2) more diluted than usual (also making him less drunk on the job than he might appear). As for the vodka…maybe that wasnt such high quality, either. And what does it say when, during the Cold War, a government agent from a nation of gin drinkers prefers the primary export of his chief rival? Bond was certainly a man of mystery.

But I digress. Getting back to opera, references to cocktails—or liquor in any form, for that matter—are few and far between. Since the art forms two most prominent roots are in Italy and Germany, wine and beer are the usual tipples. But even within those perimeters, the range of references is quite broad.

So, too, are the ways to build these into our operatic appreciation. I can already imagine home viewing parties morphing into elaborate drinking games: a sip for every time someone casually mentions some form of alcohol, a long gulp for any scene set in a drinking establishment, an entire glass during any aria or chorus predominantly featuring a fermented beverage. Some devotees of kalsarik?nnit (or “pantsdrunk,” that Finnish tradition I cited a couple of months ago about people drinking at home wearing only their underwear) are probably doing that already.

But for the time being, since Im already sitting about halfway between the bottles and the opera recordings, lets take a deeper look at the genre and see what insights we can glean from our characters choice of beverage.

“Ehi, Taverniere!”

from Verdis Falstaff (1893)

The stage has no greater authority on drinking than Sir John Falstaff, Shakespeares high-born lowlife who squanders his knighthood on a variety of disreputable pastimes. Verdis final opera opens with Falstaff already drinking; by Act III, Sir John starts out raving about “a thieving, wicked world,” then once the wine kicks in, “every fiber in the heart vibrates, and a trilling madness rocks the joyous globe.” This is when you tell the taverner, “Ill have what hes having.” For details, though, we need to go back to Shakespeare. In The Merry Wives of Windsor Falstaff mentions metheglin, a honey wine spiced with cloves and herbs, but his most reliable drink is sack, an early form of sherry stronger than regular wine and rather similar in consistency and flavor to huangjiu (which Falstaff even asks to be warmed). For the record, he never drank beer, despite at least five American breweries using Falstaffs image or name to promote their products.

“Wine or Beer?” from Gounods Faust (1859)

The relevant question opens Act II, with a chorus of students, soldiers and locals all cheerfully agreeing that “a drunkard drinks everything.”(Tellingly, my German translation is “Wine and beer,” with no question mark.) By the standards of our drinking game, this is a clean sweep, not merely set in a tavern with a recurring drinking chorus but having substantial plot developments unfold within the very definition of a “public house,” where otherwise incompatible groups find themselves sharing the same space. Soldiers are about to head off to war, Marguerite makes her first appearance, and Méphistophélès sows seeds of discontent in all quarters, partly by plying the crowd with wine from his own cellar. The fact that the liquid bursts into flames, though, shouldve made people question the vintage.

“Certain rat, dans la cuisine”

from Berliozs Damnation of Faust (1846)

Berliozs equally French take on Goethes truly German drama premiered at Pariss Opéra-Comique but only secured a place in the opera house once modern stagecraft (particularly video projections) could illuminate the storys mystical effects. Some of the overlap with Gounods version—including the tavern scene, complete with a drunken student singing about a rats revels in the kitchen ending after eating a batch of poison—stems from essential dramatic devices in Goethes telling. Though the folkloric Fausts downward spiral had long been portrayed in a seedy tavern—really, where else would you meet the Devil?—Goethe had set the scene in Auerbachs Cellar, an actual tavern in Leipzig that had been in existence since 1498. By lightening the sordid setting for comic relief, Goethe set the tone for future adaptations.

“Libiamo nelieti calici”

from Verdis La Traviata (1853)

Without doubt the most famous drinking song in all of opera, the musical backdrop where Pariss resident party girl first meets her bourgeois admirer is known simply as The Brindisi (Italian for “drinking song,” but appropriately enough, derived from the German toast (ich) bringe dirs, or “(I) offer it to you”). Stepping away from the other guests in her salon, Alfredo leads his toast with “Drink from the joyful glass, resplendent with beauty,” drawing attention to Violettas “irresistible gaze.” Violetta brushes aside the flattery, urging all her other guests to “be joyful, for love is a fleeting short-lived joy.”Still, Violetta is hooked, and indeed her love with Alfredo is short-lived. Despite weaving its dramatic subtexts, the musics pure effervescence leaves little doubt that its champagne in the glasses.

“Viva, il vino spumeggiante”

from Mascagnis Cavalleria Rusticana (1889)

Theres no doubt what Mascagnis peasants are drinking either, since the word “sparkling”is right there in the title. To be clear, Verdi wrote The Brindisi; Mascagni merely wrote “a brindisi,”but this one-act work—his first opera—essentially propelled verismo on the opera stage. Many critics have observed how this changed operatic storytelling—my favorite description is that verismo replaced adultery, seduction, murder and suicide in the highest families with adultery, seduction, murder and suicide in the lowest families—but a clear stylistic contrast is evident even in their drinking songs. As the returning soldier Toriddu leads his fellow villagers in an Easter Day toast, his girlfriends husband arrives, refuses Toriddus wine and challenges him to a duel. It doesnt end well.

“Finchhan dal vino”

from Mozarts Don Giovanni (1787)

Librettist Lorenzo Da Ponte never specifically mentions Giovannis intoxicant of choice—director Peter Sellars notoriously had the Don shooting heroin—but tradition, as they say, abhors a vacuum. Giovannis Act II paeon to wine, women and dancing has long been dubbed the “Champagne Aria,”with Mozarts music practically bubbling over with licentiousness. Running no more than 90 seconds, no aria in the history of opera has delved so aptly and efficiently into the nature of the character singing.

“Vivat Bacchus” from Mozarts

Abduction from the Seraglio (1782)

From the libertine Giovanni to the teetotal Osmin, Mozarts characters clearly run to extremes. Though the strict terms of Mozarts first imperial commission (a German-language stage work with spoken dialogue) left limited room to tell the story in purely musical term, the composer nonetheless managed to push contemporary conventions to their limits—not least the faddish appropriation of all things Turkish. Padrillos plans to free his fiancée Blonde from the clutches of Osmin, the Pashas overseer, involve incapacitating Osmin one glass at a time—despite the overseers Islamic beliefs. Allahs prohibitions soon give way, with Osmin declaring that “Bacchus is a fine fellow” and nearly shifting his allegiance to the Roman god of wine before passing out. A charming set piece, composed by a confirmed infidel.

“Drig, Drig, Drig, Ma?tre Luther”

from Offenbachs Les Contes dHoffmann (1881)

Some question still remains whether E.T.A. Hoffmann was primarily a writer who drank or a drinker who wrote. Offenbachs first (and only) true opera plays both sides, opening in Luthers Tavern with the spirits of wine and beer claiming to be the writers Muse (a romanticized version, to be sure, since Hoffmann himself died at 46, largely a victim of his “muse”). And indeed, when the chorus enters a few minutes later, it is the drinking that leads to the storytelling. The only remaining question is, well, wine or beer? Both are treated rather indiscriminately—the only exhortation being“Fill the cups till dawn”—with no obvious cultural allegience, truly befitting a composer who was born in Germany as “Jakob Eberscht” and made his musical career under the name “Jacques Offenbach”in France.

“Drink! Drink! Drink!”

from Rombergs The Student Prince (1924)

Though Offenbachs legacy in opera is negligible, his influence on operetta—and by extension, the future of musical theatre—was enormous. The difference between the two stage genres becomes apparent comparing the place of Offenbachs drinking chorus with that of Rombergs. In Hoffmann, the music runs almost continuously throughout, illustrating and often advancing the narrative; The Student Prince (with book and lyrics by Dorothy Donnelly) more or less adapted the German-language play Old Heidelberg to the American stage, its songs adding little to the story. That said, The Student Prince was the longestrunning show on Broadway in the 1920s, its popularity driven mostly on the basis of its “Drink, Drink! Drink!” chorus—a phenomenon partly explained by the fact that the United States was in the middle of Prohibition, when it was illegal to produce or sell alcohol.

“To pivecko”

from Smetanas The Bartered Bride (1866)

Amidst an admittedly wine-heavy field—stagings of Offenbach and Romberg often depict beer, but the operas themselves refuse to take sides—we finally come to a composer unafraid of commitment. Smetana, the son of a brewer, has his villagers in The Bartered Bride unambiguously declaim “Beer is a gift from heaven” at the opening of Act II. Though the operas history had a rocky start—its early incarnation, with spoken dialogue, left audiences cold—Smetana revised his score to let the music do the talking, shaping its flow to the natural rhythms and pulses in the Czech language. When two characters begin arguing that either love or money is better than beer, the other villagers simply ignore them and keep drinking—a true hallmark of authenticity from a proudly beerdrinking culture.