An unexpected electrocardiogram sign of subacute left ventricular free wall rupture: Its early awareness may be lifesaving

Hong-yi Wu, Ju-ying Qian, Qi-bing Wang, Jun-bo Ge

Shanghai Institute of Cardiovascular Diseases; Department of Cardiology, Zhongshan Hospital, Fudan University,Shanghai 200032, China

KEY WORDS: Myocardial infarction; Myocardial rupture; Electrocardiogram; Diagnosis

INTRODUCTION

In recent years major advances in the management of acute myocardial infarction (AMI) has dramatically improved the outcome. However, mortality due to mechanical complications continues to be high.[1-3]The left ventricular free wall rupture (LVFWR) is the most common cardiac rupture and is the main cause of death following AMI in-hospital.

Acute form of LVFWR was defined as abrupt hemodynamic collapse with electromechanical dissociation and the pericardial effusion,[4,5]and this rupture type is usually well-recognized. In this clinical setting, cardiopulmonary resuscitation maneuvers have very little effect, and death ensues rapidly. Subacute variant of LVFWR, which is less frequent and has not received suff icient attention, was def ined as cardiogenic shock without electromechanical dissociation and presence of pericardial effusion.[4,5]In latter setting,timely interventions can dramatically change prognosis.

Independent predictors of LVFWR include advanced age, female gender, history of hypertension, 1-vessel disease with preserved left ventricular (LV) function,first MI, absence of reperfusion therapy, and delayed admission.[6-9]However, few baseline characteristics have a high positive predictive value, highlighting need for early recognition and improved differential diagnosis.

CASES

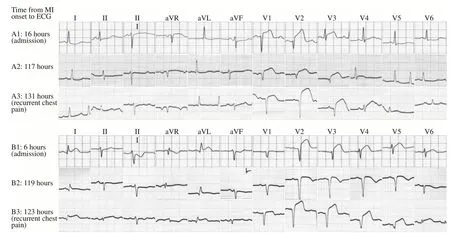

Two women in their 80s were admitted to our institute after experiencing the sudden onset of chest pain. Electrocardiogram (ECG) at admission showed ST segment elevation in anterior wall leads (Figure A1 and B1). They were managed as ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction without reperfusion treatment.As a result, the ST segment resolution was incomplete(Figure A2 and B2). Unfortunately, they experienced a recurrence of chest pain with cardiogenic shock. The ECG recorded at that time showed a ST-segment reelevation in infract-related leads and a decrease of QRS voltage in leads II, III, and aVF (Figure A3 and B3).

The patient A experienced a recurrence of chest pain in the morning of the sixth day after admission.Vital signs revealed a blood pressure of 80/50 mmHg;pulse 102 beats per minute and regular. She received a judgement of reinfarction and was treated with tirof iban.However, her blood pressure could not be kept normal with the infusion of vasoactive drugs and cardiac injury marker of reinfarction was absent. Five hours later, the patient was in a state of unconsciousness and metabolic acidosis. At this antemortem time, a bedside transthoracic echocardiogram was performed, revealing more than 10 mm pericardial effusion. All findings suggest the diagnosis of a subacute LVFWR.

The patient B also had a recurrence of severe chest pain with cardiogenic shock and new ST elevation in the infarct-related leads in the midnight of the f ifth day.Recurrent myocardial infarction was suspected, however recurrent rise of cardiac injury markers was absent. As the bedside transthoracic echocardiogram demonstrated 19 mm pericardial effusion, the diagnosis of subacute LVFWR was made. Regrettably, the family members refused invasive maneuvers, and the patient was not rescued successfully.

DISCUSSION

The ECG is a critical tool to rapidly identify patients who require time-sensitive therapies. We describe an unexpected change of ECG, coupled with recurrence of chest pain and new onset hypotension, that signifies the subacute variant of LVFWR diagnosed by echocardiography.

As the clinical presentation lacks specificity and the ECG sign may be sometimes deceptive, subacute LVFWR remains a relatively under-diagnosed condition.In a previous study including 24 patients with subacute LVFWR, the f irst 21 subjects were unrecognized before autopsy.[10]Of note, 56% of subjects in whom a prerupture ECG was available for comparison, showed new STE in infarct-associated leads, but characteristic autopsy or cardiac injury marker of infarct extension was absent.[10]There are also a few studies linking new electrocardiographic ST-elevation with subacute LVFWR.[11-13]However, given the low incidence, such association has not received sufficient attention. It is likely to be erroneously attributed to ischemia. In this situation, administration of potent antithrombotic or thrombolytic therapy is catastrophic. The exact electrophysiological mechanisms underlying the changes described are not known. ST-segment re-elevation is potentially due to blood oozing from the site of infarction to the pericardium.[13]The slow leakage blood was not severe enough to cause complete hemodynamic collapse and massive hemopericardium.

Figure 1. An unexpected electrocardiogram change of subacute left ventricular free wall rupture. These 12-leads electrocardiogram recordings of two patients showed a 1–5 mm ST-segment re-elevation in infracted leads and a decrease of voltage in leads II, III, and aVF while left ventricular free wall rupture occurring gradually.

The ECG sign of STE must be interpreted in the context of the clinical presentation. Most often, a recurrent electrocardiographic ST-elevation in the acute phase of AMI is due to coronary reocclusion or spasm.In some cases, it may also occur in ventricular aneurysm or post-infarction regional pericarditis (PIRP).[14,15]It has been demonstrated that myocardial rupture was associated with PIRP.[14]

Our cases highlight the importance of keeping a high index of suspicion while investigating a patient with AMI in whom repeat onset of STE is coupled with chest pain and hypotension. As subtle treatment can dramatically change the clinical outcome of subacute LVFWR, early awareness may be lifesaving. The key to diagnosis is the finding of a pericardial effusion, which is usually but not always hemorrhagic, with transthoracic echocardiography.[16,17]Intramyocardial contrast with other imaging modalities may constitutes evidence of cardiac rupture.[18]Pericardiocentesis can be performed for the definitive diagnosis and the relief of pericardial tamponade. It has been demonstrated that subacute LVFWR can be surgically corrected with a good longterm outcome.[1]

Funding:This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China General Program (81970298) and the National Key R&D Project (2016YFC1301300, 2016YFC1301303).

Ethical approval:Not needed.

Conf icts of interest:There is no conf lict of interest to declare.

Contributors:HW found the sign and wrote the manuscript; QW provided the cases; QJ and JG revised and edited the manuscript;All authors read and approved the f inal manuscript.

World journal of emergency medicine2020年2期

World journal of emergency medicine2020年2期

- World journal of emergency medicine的其它文章

- Availability and quality of procedural sedation and analgesia in emergency departments without emergency physicians: A national survey in the Netherlands

- Presenting patterns of dermatology conditions to an Australian emergency department

- Effect of neutrophil CD64 for diagnosing sepsis in emergency department

- Post-dilatation improves stent apposition in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction receiving primary percutaneous intervention: A multicenter, randomized controlled trial using optical coherence tomography

- Predictive role of interleukin-6 and CAT score in mechanical ventilation in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease at the acute exacerbation stage in the emergency department

- Changes in peak inspiratory f ow rate and peak airway pressure with endotracheal tube size during chest compression