Prevalence and clinical significance of pathogenic germline BRCA1/2 mutations in Chinese non-small cell lung cancer patients

Xingsheng Hu, Dongyong Yang, Yalun Li, Li Li, Yan Wang, Peng Chen, Song Xu, Xingxiang Pu, Wei Zhu,Pengbo Deng, Junyi Ye, Hanhan Zhang, Analyn Lizaso, Hao Liu, Xinru Mao, Hai Huang, Qian Chu1,Chengping Hu

1Department of Medical Oncology, Cancer Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences, Beijing 100021, China;2Department of Pulmonary Medicine, Second Affiliated Hospital of Fujian Medical University, Quanzhou 362100, China;3Department of Respiratory Medicine, West China Hospital, Sichuan University, Chengdu 610041, China; 4Department of Respiratory Medicine, Daping Hospital, Chongqing 400042, China; 5Department of Respiratory Medicine, Xinqiao Hospital,Army Medical University, Chongqing 400037, China; 6Department of Medical Oncology, Tianjin Medical University Cancer Institute and Hospital, National Clinical Research Center for Cancer; Key Laboratory of Cancer Prevention and Therapy,Tianjin; Tianjin's Clinical Research Center for Cancer , Tianjin 300060, China; 7Department of Thoracic Oncology, Tianjin Medical University General Hospital, Tianjin 300052, China; 8Department of Medical Oncology, Hunan Cancer Hospital,Changsha 410006, China; 9Department of Pathology, Xiangya Hospital, Central South University, Changsha 410008, China;10Department of Respiratory Medicine, Xiangya Hospital, Central South University, Changsha 410008, China; 11Burning Rock Biotech, Guangzhou 510300, China; 12Department of Oncology, Tongji Hospital of Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan 430022, China

ABSTRACT Objective: Germline alterations in the breast cancer susceptibility genes type 1 and 2, BRCA1 and BRCA2, predispose individuals to hereditary cancers, including breast, ovarian, prostate, pancreatic, and stomach cancers. Accumulating evidence suggests inherited genetic susceptibility to lung cancer. The present study aimed to survey the prevalence of pathogenic germline BRCA mutations (gBRCAm) and explore the potential association between gBRCAm and disease onset in Chinese advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients.Methods: A total of 6,220 NSCLC patients were screened using capture-based ultra-deep targeted sequencing to identify patients harboring germline BRCA1/2 mutations.Results: Out of the 6,220 patients screened, 1.03% (64/6,220) of the patients harbored the pathogenic gBRCAm, with BRCA2 mutations being the most predominant mutations (49/64, 76.5%). Patients who developed NSCLC before 50 years of age were more likely to carry gBRCAm (P = 0.036). Among the patients harboring classic lung cancer driver mutations, those with concurrent gBRCAm were significantly younger than those harboring the wild-type gBRCA (P = 0.029). By contrast, the age of patients with or without concurrent gBRCAm was comparable to those of patients without the driver mutations (P = 0.972). In addition, we identified EGFR-mutant patients with concurrent gBRCAm who showed comparable progression-free survival but significantly longer overall survival (P = 0.002) compared to EGFR-mutant patients with wild-type germline BRCA.Conclusions: Overall, our study is the largest survey of the prevalence of pathogenic gBRCAm in advanced Chinese NSCLC patients. Results suggested a lack of association between germline BRCA status and treatment outcome of EGFR-TKI. In addition,results showed a positive correlation between pathogenic gBRCAm and an early onset of NSCLC.

KEYWORDS Germline BRCA mutations; non-small cell lung cancer; prevalence; BRCA1; BRCA2

Introduction

Certain germline alterations predispose individuals to hereditary cancers. Approximately, 5% of breast cancer cases and 20%-30% of ovarian cancers are caused by germline alterations in the breast cancer susceptibility type 1 and 2(BRCA1andBRCA2) genes1,2. Women with germlineBRCAmutation (gBRCAm) have significantly higher lifetime risk of developing breast, ovarian, tubal, and peritoneal cancers. The overall prevalence ofgBRCAmin women ranged from 1 in 400 to 1 in 800 depending on the ethnicity3. In addition to breast and ovarian cancers, results showed thatgBRCAmadditionally conferred increased susceptibility to a spectrum of other cancers, including but not limited to, colorectal4,5,lung6, prostate7, pancreatic8, and stomach cancers7,9.

Abnormalities in the DNA repair system are central to the emergence of mutations, which ultimately result in the development of cancer10.BRCA1andBRCA2are tumor suppressor genes that participate in the DNA repair processes through homologous recombination repair (HRR) and thus contribute to the maintenance of genomic integrity.BRCA1andBRCA2act in concert to repair DNA lesions, which normally stall the DNA replication fork and/or cause DNA double-stranded breaks. Previous studies onBRCA1/2have driven the development of therapeutic strategies targeting defects in HRR, such as poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase(PARP) inhibitors, whose function is based on the inability ofBRCA-deficient cells to repair DNA lesions. Studies showed that cells with completeBRCA1/2inactivation exhibit high sensitivity to DNA damaging agents11,12. Furthermore,numerous clinical trials have demonstrated an excellent response rate ofgBRCAmcarriers to PARP inhibitors13,14.The recent approval of olaparib for ovarian cancer combined with numerous promising results from trials involving other PARP inhibitors either as a single agent or in combination with other regimens for various cancer types has demonstrated the potential use of PARP inhibitors15. In addition, along with sensitivity to PARP inhibitors,BRCAmutations have been associated with sensitivity to platinumbased chemotherapyin vitro16and in phase III clinical studies in breast17and ovarian cancers18.

Although environmental factors, such as tobacco smoking,are regarded as the primary causes of lung cancer, increasing evidence has suggested inherited genetic susceptibility to lung cancer6. Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have revealed multiple polymorphic variants as determinants of lung cancer risk19-21. However, to date, the prevalence ofgBRCAmin Chinese lung cancer patients remains elusive. In the present study, we screened 6,220 Chinese advanced NSCLC patients to survey the prevalence ofgBRCAmby sequencing the entire coding region ofBRCA1/2. We also investigated the clinical significance ofgBRCAmin advanced NSCLC patients.

Patients and methods

Patients

Sequencing results of germlineBRCAwere retrieved and retrospectively screened from 6,220 advanced (stage IIIB to IV) Chinese NSCLC patients with various histology subtypes and who underwent somatic mutation profiling for the purpose of treatment selection and genetic testing. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Xiangya Hospital(Approval No. 201705818). Patients provided written informed consent for the use of their tissue and/or blood samples for analyzing their germline mutations, as well as their clinical data. The screened cohort was recruited from ten hospitals.

Preparation of plasma cell-free DNA

Peripheral blood (10 mL) was collected, stored in ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) acid tubes, and allowed to stand in 25°C for 2 h. The supernatant was transferred to a 15-mL centrifuge tube and then centrifuged for 10 min at 16,000gat 4°C. Circulating cell-free DNA(cfDNA) was recovered from 4 to 5 mL of plasma using the QIAamp Circulating Nucleic Acid kit (Qiagen).

DNA preparation and capture-based targeted DNA sequencing

DNA quantification was performed using the Qubit 2.0 Fluorimeter with the dsDNA HS assay kits (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA). A minimum of 50 ng of DNA is required for NGS library construction. DNA shearing was performed using Covaris M220, followed by end repair,phosphorylation, and adaptor ligation. Fragments with sizes ranging from 200-400 bp were selected using AMPure beads(Agencourt AMPure XP Kit), followed by hybridization with capture probes baits, hybrid selection with magnetic beads,and PCR amplification. The quality and size range of amplified fragments were then assessed by performing bioanalyzer high-sensitivity DNA assay. Paired-end sequencing of the indexed samples was performed on a NextSeq 500 sequencer (Illumina, Inc., USA).

Germline variant calling and filtering

Germline SNVs were identified using Varscan with default parameters. Germline indels were identified using Varscan and GATK. PathogenicBRCAmutations were determined by a clinical molecular geneticist according to the guidelines of American College of Medical Genetics (ACMG). ClinVar and Enigma were used during manual curation for final confirmation of the results.

Somatic sequencing data analysis

Sequence data were mapped to the reference human genome(hg19) using BWA aligner 0.7.10. Local alignment optimization, variant calling, and annotation were performed using GATK 3.2, and VarScan. Plasma samples were compared to their corresponding white blood cell controls to identify somatic variants. Variants were filtered using the VarScan fpfilter pipeline. Loci with depths of less than 100 filtered out. At least 2 and 5 supporting reads were required for INDELs in plasma and tissue samples,respectively, while 8 supporting reads were required for SNV calling in both plasma and tissue samples. According to the ExAC, 1000 Genomes, dbSNP, ESP6500SI-V2 database,variants with population frequencies higher than 0.1% were classified as SNPs and excluded from further analysis. After filtering, the remaining variants were annotated with ANNOVAR and SnpEff v3.6. DNA translocation analysis was performed using Factera 1.4.3.

Statistical analysis

All data were analyzed using R software. Survival data were analyzed by Kaplan-Meier and log-rank test to compare the differences between the survival groups. Differences in groups were calculated and presented using paired, twotailed Student’st-test.P< 0.05 was considered as statistically significant. Thep-values were adjusted for variables, such as age, gender, and pathological stage, when applicable.

Results

Patient characteristics

We conducted a retrospective nationwide multicenter study across ten hospitals to survey the prevalence rate ofgBRCAmin advanced (stage IIIB to IV) Chinese NSCLC patients with various histological subtypes. Patients who initially underwent NGS-based molecular testing for treatment guidance were included in the study. The WBCs were additionally sequenced for the purpose of filtering out germline mutations. Sequencing results of WBCs were retrieved and screened forgBRCAmstatus. The screened cohort comprised 3,412 males and 2,809 females with a median age of 63.2 years. The majority of the patients (4,752;76.4%) were diagnosed with adenocarcinoma, followed by 765 patients (12.3%) with squamous cell carcinoma,51 patients (0.82%) with large cell carcinoma (LCC),31 patients (0.5%) with adenosquamous carcinoma, and the remaining 621 patients with other subtypes. A total of 1,089 patients were treatment-naïve, while the remaining 5,131 patients previously received treatment. We identified 64 patients with pathogenicgBRCAmand had a median age of 59 years; of these, 26 were females and 38 were males.Fifty-five patients were diagnosed with adenocarcinoma, two with LCC, two with squamous cell carcinoma, and the remaining five patients with NOS; of these, 43 patients were non-smokers, 13 were smokers, and the remaining eight patients had no information regarding smoking history.Thirty-five of them were treatment-naïve. Patient demographics of the cohort with pathogenicgBRCAmare summarized in Table 1.

Prevalence of gBRCA1/2 mutations

Of the 6,220 NSCLC patients screened, we detected 64 pathogenic and 699 variants of unknown significance(VUS) germlineBRCAvariants. Overall, we identified 64 patients harboring pathogenicgBRCAm, corresponding a prevalence of 1.03% (64/6,220). Results revealed a gBRCA2predominance with 15 (23.4%) gBRCA1loss-of-function(LOF) mutation carriers and 49 (76.6%) gBRCA2LOF mutation carriers. Consistent withgBRCAmfindings reported in other cancer types, the mutations were found to be evenly distributed between the two genes, and no particular hotspots were identified. The distributions of gBRCA1/2mutations are presented in Supplementary Figure S1A-S1B.Among the pathogenic gBRCA2variants, we observed four types of mutations, with frameshift mutations being the most predominant mutation type accounting for 57.2% (28/49),followed by nonsense/stop gain point mutations with 24.5%(12/49), splice-site variants with 14.3% (7/49), and the remaining missense variants with 4%. Meanwhile, the majority of the pathogenicBRCA1variants were nonsense mutations (8/15), followed by frameshift mutations (5/15)and splice-site mutations. No gBRCA1pathogenic missense mutations were identified in our cohort. Furthermore, we detected several mutations, including R1443* in gBRCA1and D252fs, Q1037*, R2336L, and exon 16 splice site variant in gBRCA2, in at least two patients from our cohort.

Table 1 Demographics of 64 patients with pathogenic germline BRCA1/2 mutations

Somatic mutation spectrum of patients with gBRCAm

Figure 1 Somatic mutational profiles of 64 patients carrying pathogenic gBRCAm. Columns represent patients. Rows represent genes. Top bars represent the number of mutations per patient. Side bars represent the percentage of patients with the mutation. Colored boxes indicate different mutation types.

In addition to analyzing thegBRCAmstatus of the lung cancer patients in our cohort, we investigated somatic mutations associated with patients harboringgBRCAm.Somatic mutation profiling was conducted using a panel consisting of 56 lung cancer-related genes spanning 330 kb of the human genome. Collectively, we identified 164 somatic mutations spanning 31 genes. A total of 47 patients harbored the following classic lung cancer driver mutations: 33 withEGFR, 3 withALK, 6 withKRAS, 5 withMET, 1 withERBB2,1 withROS1, and 2 withBRAFmutations (Figure 1). Four patients had multiple driver mutations, and six patients had no mutations detected based on this panel.EGFRwas most frequently mutated gene, occurring in 53% of patients,followed byTP53andPIK3CA, occurring in 47% and 12% of patients, respectively. Six patients (9%) harbored somaticBRCA2mutations corresponding to two nonsense, one synonymous, one splice site, and two missense mutations.Other frequently occurring somatic mutations includedMYC(9%),CDKN2A(8%), andAPC(6%). Next, we examined whether there is a difference in the somatic mutation spectra in patients withgBRCA1andgBRCA2mutations. Our findings revealed that patients harboringgBRCA1orgBRCA2mutations had comparable mutation profiles (Figure 1).Taken together, the somatic mutation profiles of patients withgBRCAmwere comparable to those of patients harboring wild-type germlineBRCA1/2. We observed no significant differences in the somatic mutation spectra of patients with the gBRCA1and gBRCA2mutations.

gBRCAm is more prevalent in patients with early disease onset

Numerous studies have suggested correlations betweengBRCAmand the early onset of disease in several cancer types, including lung cancer. First, we investigated whethergBRCAmis associated with early onset of NSCLC in Chinese patients. The screened cohort comprised 947 patients diagnosed before age of 50; among them, 16 harboredgBRCAm, corresponding to a prevalence rate of 1.69%. A total of 4,945 patients were diagnosed at or after the age of 50; of these, 45 patients weregBRCAmcarriers,corresponding to a prevalence of 0.91%. Our results revealed that patients with an onset of disease before 50 were more likely to havegBRCAm(P= 0.036) (Figure 2A). Importantly,it is well-established thatALKfusions tend to occur in younger patients; therefore, patients withALKfusions were excluded from the analysis. In addition, results indicated that patients withgBRCAmtend to carry classic driver mutations for lung cancer (P= 0.076, Figure 2B). Further analysis revealed that among patients harboring driver mutations,those with concurrentgBRCAmwere significantly younger compared to patients with wild-type (WT) gBRCA(P=0.029, Figure 2C). We observed no significant differences in age between patients withgBRCAmand WT gBRCAamong patients without the driver mutations (P= 0.972, Figure 2C).Furthermore, among the patients withgBRCAm, those with concurrent driver mutations were younger than patients without the driver mutations (P= 0.032, Figure 2D). In addition to driver mutations, we identified a positive correlation betweengBRCAmwith somaticBRCA2mutations (P= 0.034, Figure 2E) and a marginal positive correlation betweengBRCAmandPIK3CAmutations (P=0.055, Figure 2F). SomaticBRCA2mutations are likely to act as the second hit for tumorigenesis. In our cohort, we identified six patients with germlineBRCA2mutations who carried concurrent somaticBRCAmutations; five of these patients harbored aBRCA2mutation and one hadBRCA1mutations. Taken together, our findings suggested thatgBRCAmpredisposes patients for the development of lung cancer.

Survival analysis of patients with gBRCAm

Figure 2 Relationship between gBRCAm and clinical and molecular features. (A) Germline BRCA mutations are more likely to occur in patients < 50 years of age. (B) Association between germline BRCA status and the presence of driver mutations. Blue bars denote the presence of driver mutations; red bars denote the lack of driver mutations. X-axis denotes the status of germline BRCA. (C) In the absence of driver mutations, no age difference was observed between patients with (+) or without (-) germline BRCA mutations. (D) In the presence of driver mutations, patients with germline BRCA mutations are younger. X-axis denotes the presence or absence of classic lung cancer driver mutations. (E) Association between germline BRCA status and somatic BRCA2 mutation. (F) Association between germline BRCA status and somatic PIK3CA mutation. X-axis indicates the gBRCAm status, (-) denotes wild-type status, while (+) represents mutation carriers. Y-axis indicates the percentage of patients with the somatic molecular features being observed. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

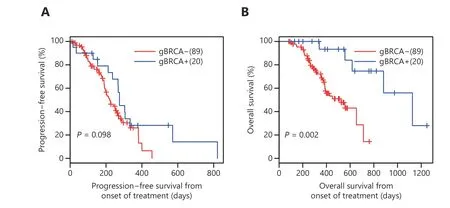

Previous studies reported that patients withgBRCAm are more sensitive to platinum-containing chemotherapy18,22.Next, we investigated the efficacy of chemotherapy in 13gBRCAmtreatment-naïve patients who were ineligible for targeted therapy. These patients had a median progressionfree survival (PFS) of 9.9 months and median overall survival(OS) of 26 months (Figure 3A-3B).

Next, we additionally evaluated the efficacy of EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) in 20 patients harboringEGFRactivating mutations and treated with first-generation EGFR-TKI. The study included a cohort of 89 patients harboringEGFRmutations but had WT gBRCAand treated with EGFR-TKI at the Xiangya Hospital. Patients withgBRCAmhad a comparable median PFS with patients harboring WT gBRCA(9.2vs. 7.3 months), after adjusting for age, gender, and disease stage (P= 0.098) (Figure 4A).Interestingly, the overall survival (OS) of patients with concurrentgBRCAmwas significantly longer than that of EGFR-TKI-treated patients harboring WT gBRCA(37.5 monthsvs.17.4 months,P= 0.002, Figure 4B).

Figure 3 Treatment outcomes and overall survival of patients with pathogenic germline BRCA mutations treated with platinum-containing chemotherapy. (A) Progression-free survival (PFS) and (B) overall survival (OS) from the day of treatment of 13 patients who received platinum-containing chemotherapy as first-line treatment.

Discussion

Figure 4 Treatment outcomes and overall survival of EGFR-mutant patients with pathogenic germline BRCA mutations treated with EGFR inhibitor. (A) Progression-free survival (PFS) and (B) overall survival (OS) from the day of treatment of 20 patients who received firstgeneration EGFR inhibitor as first-line treatment.

In the present study, we analyzed the incidence ofgBRCAmin advanced Chinese NSCLC patients (stage IIIB to IV). To the best of our knowledge, our study is the first and largest cohort to investigate the prevalence ofgBRCAmin Chinese NSCLC patients, which was found to be 1.03% ofgBRCAmwith a predominance ofBRCA2(49/64, 76.5%). ThisBRCA2predominance was previously observed in prostate cancer patients23. However, the majority ofgBRCAmin ovarian cancer are predominantly composed ofBRCA1mutations(172/235, 73.2%)2. In prostate cancer, patients with germlineBRCA2mutations showed elevated global genomic instability and harbored unique mutations that were rarely or not yet been reported in sporadic localized prostate cancer24,25.However, our findings revealed that NSCLC patients harboring gBRCA2mutations had comparable mutation spectra to those of patients harboring gBRCA1, as well as patients with WT gBRCA.

Previous studies have established the association betweengBRCAmand the development of various cancers, including but not limited to breast, ovarian, prostate, pancreatic and stomach cancers. GermlineBRCAmutation associated cancers present with distinct clinical behaviors often characterized by an earlier onset, improved efficacy of certain treatments, and more favorable survival26,27However, the role ofBRCAmutations in NSCLC remain elusive. Our results revealed a positive association betweengBRCAmand the early onset of NCSLC. Patients withgBRCAmwere significantly more likely to develop NSCLC before the age of 50 (P= 0.036). Interestingly, patients with concurrentgBRCAmand mutations in classic lung cancer driver genes were also found to develop NSCLC at a younger age (P=0.029). However, this phenomenon was not observed in patients without mutations in driver genes.

While the clinical relevance ofgBRCAmhas been wellestablished in multiple types of cancer, the significance of somaticBRCAmutations is beginning to be understood. Our cohort has sixgBRCAmcarriers with concurrent somaticBRCAmutations, suggesting that the somaticBRCAmutation could act as a second hit for the development of tumorigenesis (Table 2). Interestingly, two of these patients,namely, patients 3 and 6, harbored the germline and somaticBRCA2mutations on the same amino acid residue (i.e.Arg1694 and Ser2984) but with different mutation types.

Despite very poor survival outcomes, platinum-based chemotherapy remains the standard therapy for the majority of heavily-treated advanced NSCLC patients, who have a median progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival(OS) of 3.6 months and 7.9 months, respectively28. Enhanced sensitivity to platinum-containing chemotherapy has been associated with germlineBRCAmutations based on preclinical and clinical studies on ovarian and breast cancers17,18.In the present study, we consistently observed the good efficacy of chemotherapy ingBRCAmtreatment-naïve patients with PFS and OS of 9.9 months and 26 months,respectively. Interestingly, patients with concurrentgBRCAmand somaticEGFRmutations also showed a tendency to respond well to EGFR-TKI compared to patients withoutgBRCAm. In addition to investigating somatic mutations,studying the germline genetic status of lung cancer patients is also important for understanding their genetic landscape and for guiding clinical decisions.

The present study has certain limitations. Numerous cancer predisposing genes, mostly tumor suppressors, have been identified29. This study was only limited to the identification of pathogenic mutations. Further studies are required to elucidate the clinical significance of other pathogenic cancer predisposing genes in NSCLC. Numerous studies revealed that not allBRCAgermline mutations resulted in the locus-specific loss of heterozygosity (LOH)and further reported the differential clinical significance betweenBRCALOH mutations and non-LOH mutations.Unfortunately, panels used in this study cannot detect LOH.Only patients with advanced disease were screened (stage IIIb to IV) and analyzed. Future studies that include patients in the early stages of the disease are needed to provide a more comprehensive understanding of gBRCAstatus. The lack of family history also limits further investigation.

Table 2 Mutational profile of the patients with germline and somatic mutations in BRCA1/2

In conclusion, to the best of our knowledge, we have conducted the largest and most comprehensive survey of the prevalence of pathogenicgBRCAmin Chinese NSCLC patients. Results revealed a positive correlation between pathogenicgBRCAmand early onset of NSCLC.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grant from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 81502699).

Conflict of interest statement

JY, HH-Z, AL, HL, XM and HH are employees of Burning Rock Biotech. The other authors declare no conflict of interest.

Cancer Biology & Medicine2019年3期

Cancer Biology & Medicine2019年3期

- Cancer Biology & Medicine的其它文章

- TNFα inhibitor C87 sensitizes EGFRvIII transfected glioblastoma cells to gefitinib by a concurrent blockade of TNFα signaling

- A four-gene signature-derived risk score for glioblastoma:prospects for prognostic and response predictive analyses

- Prediction of cervical lymph node metastases in papillary thyroid microcarcinoma by sonographic features of the primary site

- Decrease in the Ki67 index during neoadjuvant chemotherapy predicts favorable relapse-free survival in patients with locally advanced breast cancer

- Incidence, distribution of histological subtypes and primary sites of soft tissue sarcoma in China

- Incomplete radiofrequency ablation provokes colorectal cancer liver metastases through heat shock response by PKCα/Fra-1 pathway