Hippocrates: The Father of Modern Medicine“医学之父”希波克拉底

特蕾西·佩德森

Hippocrates of Kos1 was a Greek physician who lived from about 460 B.C. to 375 B.C. At a time when most people attributed sickness to superstition2 and the wrath3 of the gods, Hippocrates taught that all forms of illness had a natural cause. He established the first intellectual school devoted to teaching the practice of medicine. For this, he is widely known as the “father of medicine.”

Approximately 60 medical documents associated with his name, including the famous Hippocratic oath4, have survived to this day. These documents were eventually gathered into a collection known as the Hippocratic Corpus5. While Hippocrates may not have written all of them himself, the papers are a reflection of his philosophies. Through Hippocrates’ example, medical practice pointed in a new direction, one that would move toward a more rational and scientific view of medicine.

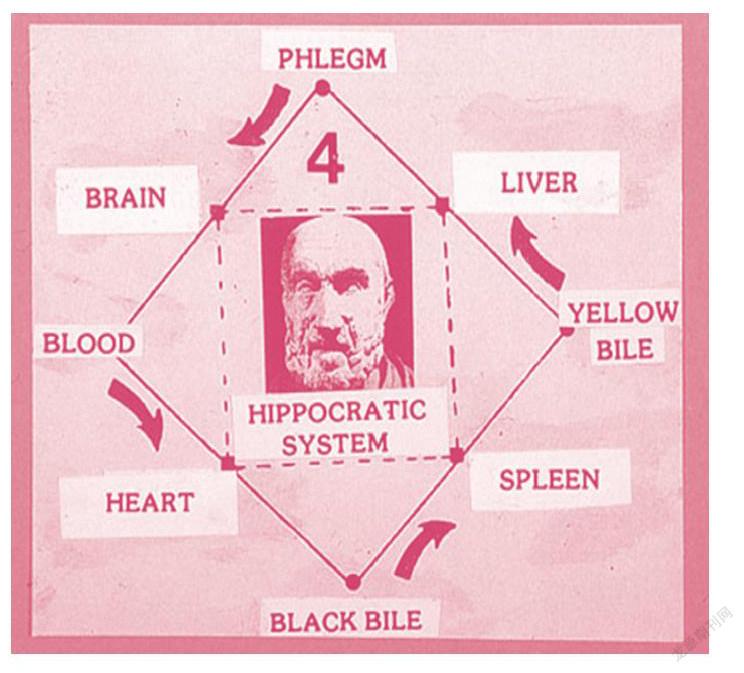

The four humors

Hippocrates is often credited with developing the theory of the four humors6, or fluids. Philosophers Aristotle and Galen7 also contributed to the concept. Centuries later, William Shakespeare incorporated the humors into his writings when describing human qualities.

The humors were yellow bile8, black bile, blood and phlegm9, according to “The World of Shakespeare’s Humors,” an exhibition by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) 10. Each humor was associated with a particular element (earth, water, air or fire), two “qualities” (cold, hot, moist, dry) 11, certain body organs and certain ages (childhood, adolescence, maturity, old age).

The interactions among the humors, qualities, organs and ages—as well as the influence of the seasons and planets—determined a person’s physical and mental health, as well as their disposition12 or personality. (Galen used the term “temperament13” and literally14 meant that health and personality were affected by temperature—cold, hot, dry or wet. This notion is reflected in the idioms “catching a cold” or having a “dry sense of humor.”)

According to the theory:

Yellow bile is related to the choleric15 disposition and the qualities of hot and dry. It is associated with fire, summer, the gallbladder16 and childhood.

Black bile is related to the melancholic17 disposition and the qualities of cold and dry. It is associated with earth, winter, the spleen18 and old age.

Blood is connected to the sanguine19 disposition and the qualities of hot and moist. It is linked to air, spring, the heart and adolescence.

Phlegm is related to the phlegmatic20 disposition and the qualities of cold and moist. It is connected to water, the brain and maturity.

Differences due to age, gender, emotions and disposition could be attributed to the interactions of the humors, according to the NIH exhibition. Heat stimulated action; cold depressed it. Someone with a choleric disposition was courageous, but phlegm caused cowardice21. Youth was hot and moist; age was cold and dry.

According to the ancient theory, the key to good health was to keep the humors in balance; an excess22 or deficiency23 in one or more of the humors was associated with disease. Sometimes the doctor would let blood (open a vein24 and drain25 the patient’s blood) or prescribe26 emetics27 (medicine that causes vomiting) in order to balance the humors.

These ideas represented the first step away from the predominantly28 supernatural view of sickness and a step toward a new idea that illness is related to the environment and what is going on inside the body.

Hippocratic oath

Often included in the Hippocratic Corpus is the Hippocratic oath, an ancient code of ethics29 for doctors. Today, the oath is valued as more of a historic example of medical ethics and principles rather than one to be taken completely literally.

The following is a modern version of the oath written in 1964 by Dr. Louis Lasagna, then a professor of medicine at Johns Hopkins University and later dean of the Sackler School of Graduate Biomedical Sciences at Tufts University:

I swear to fulfill, to the best of my ability and judgment, this covenant30:

I will respect the hard-won31 scientific gains of those physicians in whose steps I walk, and gladly share such knowledge as is mine with those who are to follow.

I will apply, for the benefit of the sick, all measures [that] are required, avoiding those twin traps of overtreatment 32 and therapeutic nihilism33.

I will remember that there is art to medicine as well as science, and that warmth, sympathy, and understanding may outweigh34 the surgeon’s knife or the chemist’s drug.

I will not be ashamed to say “I know not,” nor will I fail to call in my colleagues when the skills of another are needed for a patient’s recovery.

I will respect the privacy of my patients, for their problems are not disclosed to me that the world may know. Most especially must I tread with care in matters of life and death. If it is given me to save a life, all thanks. But it may also be within my power to take a life; this awesome responsibility must be faced with great humbleness and awareness of my own frailty35. Above all, I must not play at God.

I will remember that I do not treat a fever chart36, a cancerous37 growth, but a sick human being, whose illness may affect the person’s family and economic stability. My responsibility includes these related problems, if I am to care adequately for the sick.

I will prevent disease whenever I can, for prevention is preferable to cure.

I will remember that I remain a member of society, with special obligations to all my fellow human beings, those sound of mind and body as well as the infirm.

If I do not violate this oath, may I enjoy life and art, respected while I live and remembered with affection thereafter. May I always act so as to preserve the finest traditions of my calling and may I long experience the joy of healing those who seek my help.

Though many of today’s physicians believe the oath is inadequate to address today’s economic, political and social challenges, doctors still hold sacred its principles: treat the sick to the best of one’s ability, keep them from harm and injustice, preserve patient privacy and teach the secrets of medicine to the next generation.

科斯岛的希波克拉底是古希腊医师,大约生活于公元前460年至公元前375年。时人大都将疾病归咎于迷信和神怒,而希波克拉底则教导世人,举凡疾病,不论类型,皆由自然原因所致。他创立了第一所研究学校,专门传授医道。为此,世人将他尊为“医学之父”。

与其名相关的医学文献,约有60种存世至今,包括著名的希波克拉底誓词。这些文献最终汇编成集,称作《希波克拉底文集》。虽然这些文献可能并非全部出自希波克拉底一人之手,却反映了他的哲学思想。希波克拉底垂范后世,为行医之道指明了新的方向,这一新的方向趋于一种更加理性、合乎科学的医学理念。

四种体液

众所周知,希波克拉底提出了四种体液或流质的学说。哲学家亚里士多德和盖伦也为这一思想作出了贡献。几百年后,威廉·莎士比亚描述人类特性时将体液的概念融入了其作品。

根据美国国家卫生研究院举办的“莎士比亚笔下的体液世界”展览,这四种体液是黄胆、黑胆、血液和黏液。每种体液都和某种元素(土、水、风、火)、两种“特质”(冷、热、潮、干)、某种身体器官和某种年龄(童年、少年、壮年、老年)息息相关。

体液、特质、器官、年龄之间的相互作用——以及季节、星球的影响——决定了一个人的身心健康,以及性格或个性。(盖伦使用“气质”一词,字面意思是健康和个性都受温度影响——冷、热、干、湿。catching a cold[“得了感冒”]或者having a dry sense of humor[“有种冷幽默”]这样的习语就反映了这一观念。)

根据这一理论:

黄胆质的人性格易怒,体质干热。黄胆与火、夏天、胆囊和童年有关。

黑胆质的人性格忧郁,体质干冷。黑胆与土、冬天、脾脏和老年有关。

多血质的人性格乐观,体质湿热。血液与风、春天、心脏和少年有关。

黏液质的人性格冷静,体质湿冷。黏液与水、大脑和壮年有关。

根据国家卫生研究院的展览,年龄、性别、情感和性格所产生的差异可归因于体液之间的相互作用。热促进行动,冷抑制行动。性格易怒的人胆大,黏液质的人则胆小。青春湿热,老年则干冷。

根据古代理论,平衡体液是健康的关键;疾病与某种体液或多种体液过剩或不足有关。有时候,为了平衡体液,医生会放血(割开静脉让病人的血淌出)或者开催吐剂(促使呕吐的药物)。

这些观念代表了摆脱关于疾病的主流迷信说的第一步,这一步迈向了一种全新的理念,即疾病与环境以及身体的内部运作有关。

希波克拉底誓词

《希波克拉底文集》往往收录希波克拉底誓词,这篇誓词是古代行医伦理规范。今天,这篇誓词更被人奉为医者伦理和职业操守的历史典范,而非讓人照本宣科。

以下是这篇誓词的现代版本,由时任约翰·霍普金斯大学医学教授、后任塔夫茨大学萨克勒生物医学研究生院院长路易·拉萨尼亚博士于1964年所撰:

我誓尽己力与识见所及,矢守此约:

我将尊重步其履后的先贤医者得来不易的科学成果,凡我所知,亦乐与后来者共享。

我将竭尽一切方法,造福病者,避免治疗过当与治疗虚无主义的双重陷阱。

我将谨记,医疗既是科学,亦是艺术,热诚、体恤、谅解胜于外科医生的手术刀与药剂师的药物。

我将不以“不懂”为耻,病者痊愈若需他人之助,我亦不避援请同业。

我将尊重病者隐私,因病患相告,本恐他人知晓。生死攸关之事,我犹应小心处理。若能救人一命,心存感念。然我能力所及,亦可夺人性命;重任在前,须怀有极大的谦卑之心,认清自身弱点。首先,切莫以上帝自居。

我将谨记,我治疗的并非一张发热图,亦非癌症的增殖,而是一个患病之人,他的病可能会影响其家人与经济稳定。如我充分关怀病者,我的职责亦当包括这些相关问题。

我将随时预防疾病,因为预防胜于治疗。

我将谨记,我是社会一员,对人类同胞怀有特殊义务,不论老弱抑或身心健全之人。

我若守此约誓,愿我安享人生及技艺,有生之年受人尊敬,待到身后受人缅怀。愿我一如既往,守医业优良传统。病者求援,手到病除,愿我长得此乐。

尽管今日许多医者认为这篇誓词不适于应对今日的经济、政治和社会挑战,但是医生仍然坚守这神圣的原则:尽己之力医治病者,使病者免遭伤害与不公,保护病者隐私,将医学之秘传于后代。

(译者为“《英语世界》杯”翻译大赛获奖选手)

——希波克拉底