Exploring Comprehension

Diane Barone

ABSTRACT: This article considers three critical elements of comprehension. The first element is Reading to Students where listeners expand their comprehension with the support of a more experienced reader. The second element is Independent Reading where students have the opportunity to read books of their own choice. Through choice, students experience engagement with the books they read. The third element is Instruction where students participate in literature circles. This instructional experience allows for groups of students to develop complex interpretations of text.

KEY WORDS: comprehension; reading aloud; independent reading; literature circles

In this conversation about comprehension, I focus on three critical elements or ways to engage students. The first is Reading to Students where students participate by listening to the reading of a more experienced reader. The second is Independent Reading where students have opportunities to read for pleasure. And the third is Instruction where the teacher supports students in developing more complex interpretations of text.

Reading to Students

“She wasnt always a bad kitty. She used to be a good kitty, until one day…”(Nick Bruel, Bad Kitty)

If an experienced reader read these words to you, how would you not want him/ her to continue? Listeners would certainly want to know what happened on that one eventful day. This desire to hear more is the magic that comes from reading aloud to students. Students have the opportunity to imagine a wealth of experiences through the support of a more experienced reader. And for some, very fortunate children, they share in an enchanted reading moment where “The story is read aloud, but unfettered by anything before, during, or after that resembles a skills or strategy lesson.” (Cooper, 2009) Cooper writes further, that perhaps the strength of reading aloud, when not connected to a comprehension strategy, has attracted little attention because its direct relationship to comprehension has not been evident in current research.

While there are many advocates of reading aloud to students, the most passionate and vocal ones are: Mem Fox, Jim Trelease, Ralph Peterson and Maryann Eeds. Following are examples of their writing to inspire adults to read aloud to children.

“The fire of literacy is created by the emotional sparks between a child, a book, and the person reading. It isnt achieved by the book alone, nor by the adult whos reading aloud—its the relationship winding between all three, bringing them together in easy harmony.”(Fox, 2008)

“Reading aloud and talking about what were reading sharpens childrens brains. It helps develop their ability to concentrate at length, to solve problems logically, and to express themselves more easily and clearly. The stories they hear provide them with witty phrases, new sentences, and words of subtle meaning.”(Fox, 2008)

“Whenever I visited a classroom, Id save some time at the end to talk about reading. Id begin by asking, ‘What have you read lately? Anybody read any good books lately? To my dismay, I discovered they werent reading much at all. I slowly began to notice one difference. There were isolated classrooms in which kids were reading—reading a ton… In every one of the turned-on classrooms, the teacher read to the class on a regular basis.” (Trelease, 2006)

“We read aloud to children for all the same reasons we talk with children: to reassure, to entertain, to bond, to inform or explain, to arouse curiosity, to inspire. But in reading aloud, we also:

●Condition the childs brain to associate reading with pleasure;

●Create background knowledge;

●Build vocabulary;

●Provide a reading role model.”(Trelease, 2006)

“Reading aloud is also meant to promote pleasure and enjoyment—to bring joy to life in school.” (Peterson & Eeds, 2007)

“Reading aloud also gives children the opportunity to take up ways of thinking about story that can deepen their understanding. Sometimes a comment by the teacher or another student following a selection read aloud can illuminate meaning for all.” (Peterson & Eeds, 2007)

The words of these writers are important for encouragement and for teachers to return to the days when finding time to read aloud just didnt happen. They also shore up the multiple benefits of reading aloud.

While the previous quotes include many reasons for reading aloud, the following list of 20 reasons targets those already shared and others equally important so that the benefits of reading aloud are explicit.

Reading aloud:

1. Increases test scores. (Anderson et al., 1985; Kersten et al., 2007; Serafini& Giorgis, 2003)

2. Promotes positive emotional connections between books and readers.(Butler, 1975; Cochran-Smith, 1984; Fox, 2008; Esquith, 2007; Peterson & Eeds, 2007; Trelease, 2006)

3. Extends a childs attention span.(Fox, 2008; Trelease, 2006)

4. Enlarges vocabulary knowledge.(Barone & Youngs, 2008a; Barone & Youngs, 2008b; Fox, 2008; Hancock, 2000; Trelease, 2006)

5. Provides rich, language models.(Barone & Xu, 2008; Barone & Youngs, 2008a; Barone & Youngs, 2008b; Gunning, 2010; Trelease, 2006)

6. Expands literal, inferential, and critical comprehension. (Barone& Youngs, 2008a; Barone & Youngs, 2008b; Gunning, 2010; Keene & Zimmermann, 2007; Peterson & Eeds, 2007; Sumara, 2002; Tompkins, 2010; Wolf, 2004)

7. Builds connections to other books, life, and world events. (Peterson& Eeds, 2007; White, 1956; Wolf, 2004; Wolf & Heath, 1992)

8. Widens childrens imagination.(Cooper, 2009; Wolf, 2004; Wolf & Heath, 1992)

9. Creates lifelong readers. (Butler, 1975; Peterson & Eeds, 2007; Trelease, 2006)

10. Develops and creates background knowledge. (Fox, 2008; Trelease, 2006)

11. Builds a community of learners.(Esquith, 2007; Gambrell, 1996; Guthrie, 2004; Johnson & Giorgis, 2007; Peterson& Eeds, 2007; Serafini & Giorgis, 2003; Wolf, 2004)

12. Develops students reading engagement. (Hancock, 2000; Peterson& Eeds, 2007; Tunnell & Jacobs, 2008; Wilhelm, 2008)

13. Supports developing knowledge of authors, illustrators, titles, literary genres, and text structures. (Barone& Youngs, 2008a; Barone & Youngs, 2008b; Serafini & Giorgis, 2003; Wolf, 2004)

14. Helps with finding out about almost anything. (Barone & Youngs, 2008a; Barone & Youngs, 2008b; Cochran-Smith, 1984; Gunning, 2010; Hancock, 2000; Serafini & Giorgis, 2003)

15. Models that books are valued possessions. (Cochran-Smith, 1984)

16. Affords opportunities of conversation centered on text or illustration. (Barone & Youngs, 2008a; Barone & Youngs, 2008b; Peterson & Eeds, 2007; Serafini & Giorgis, 2003; Wilhelm, 2008)

17. Increases students interest in independent reading. (Esquith, 2007; Serafini & Giorgis, 2003)

18. Offers models for writing.(Hancock, 2000; Serafini & Giorgis, 2003; Tompkins, 2010)

19. Builds fluency through listening to fluent models. (Bandré et al., 2007; Serafini & Giorgis, 2003)

20. Refines self-identity. (Sumara, 2002)

These benefits are realized through the process of reading aloud enriched with student discussion and / or other forms of response. They should help teachers relax a bit as reading to students honors the literacy expectations that are part of their curriculum and allows students to be engaged in reading.

Independent Reading

Independent reading allows students to choose their own books and read at their own pace. Miller (2009) writes,“Reading is not an add-on to the class. It is the cornerstone. The books we are reading and what we notice and wonder about our books feed all of the instruction and learning in the class.” Her words highlight the centrality of independent reading to foster reading development. Opportunities to read independently support students in multiple ways:

●They gain practice in using the skills and strategies taught by their teachers and become better readers.(Allington & McGill-Franzen, 2003)

●They provide authentic literacy experiences where students can select their own books.

●They learn to select texts.

●They enhance motivation for readers. (Gambrell, 2009)

●They develop lifelong readers.(Tompkins, 2010)

Even with the strengths of independent reading, some teachers may still view independent reading as a supplement to reading instruction. Gunning (2008) argues that there is no reading program that provides sufficient fiction and nonfiction material for students to fully develop literacy. While the research about independent reading is robust in its support of literacy gains, the research also indicates that students are spending less time reading in their classrooms and at home (U.S. Department of Education, 2005). Gambrell (1984) observed that first graders actually read for about 3 minutes per day and second and third graders about 5 minutes per day. More recently, Brenner, Hiebert, and Tompkins (2009) noted that third graders spent about 18 minutes per day really reading. This amount of time begs the question as to whether this amount of reading time is sufficient for novice readers to develop proficiency.

Further, Mol and Bus (2011) reviewed studies in a meta-analysis of preschoolers to high school students to determine the importance of reading volume to comprehension. The effect size of preschool and kindergarten children was 0.35. For first through fourth graders, the effect size was 0.38. For students in the fifth through eighth grade, the effect size was 0.48. For students in the ninth through twelfth grade, the effect size was 0.61. They noted that print exposure and comprehension become stronger as students become maturer. They also discovered that print exposure explains more variance in children with basic reading skills than in students with ageappropriate reading skills. Moreover, they wrote, “Interestingly, independent reading of books also enables readers to store specific word form knowledge and become better spellers.”

Barone and Barone (2016) discovered that students in an elementary school with high achievement as measured by standardized tests did not see themselves as readers. Students talked about disliking reading and rarely if ever reading a book in class or at home. The researchers explored with students who they thought were readers. The students were clear that when you can decode words you are a reader but not a reader who loves to read. They identified the following criteria to determine if one is a reader who loves reading:

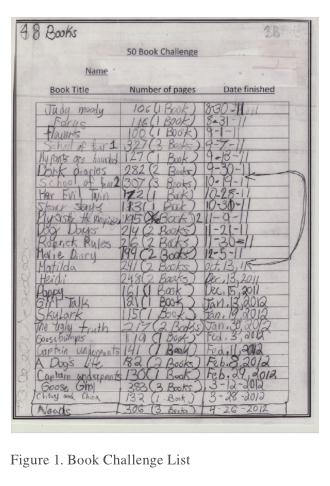

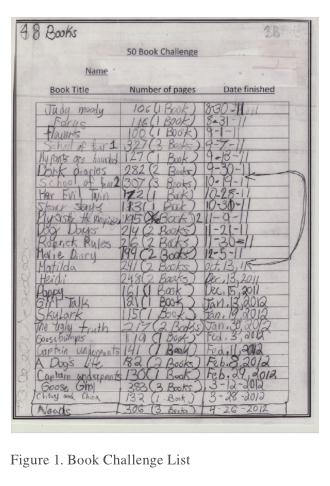

In an investigation where achievement and independent reading were studied, Barone and Barone (2017) discovered that extensive independent reading paralleled reading achievement. Students were asked to read 50 books during an academic year outside of any reading expected during instruction. Students recorded their books in a journal (see Figure 1) where 200 pages of reading equalled one book. Jotting down the title of a book and its pages was the only expectation for students. However, their teacher routinely talked with students about what they were reading and what they thought about the books but there were no quizzes or projects related to the reading. At the end of the year, the 28, fourth grade students read 1227 books. 12 students read 50 or more books. 3 students read more than 80 books, 1 read 70 books, and the other 8 read 50 to 59 books. 4 students read 40 to 49 books. The remaining students read from 39 to 3 books. While the study was not causal, 96% of the students met the proficiency expectations set by the state in their annual examinations.

What was particularly interesting about this investigation is that students loved the choice in reading. They talked about the books they were reading with peers and then another student would read that particular book. This effect was noticeable when students chose books from a series to read. Immediately, other students wanted to read the same series. Students were proactive in begging the librarian and their teacher to purchase more copies of the books so they would have access to them.

Instruction

While there are all kinds of instructional support that can be given to a student, I am focusing on literature circles where students read books in small, heterogeneous groups and respond through writing or drawing, and then engage in conversation.

Is it important for students to talk about the books they read? Isnt it just important for students to read independently? The answer to both questions is yes. Certainly students need to read independently and choose the books they want to read to improve motivation and skill in literacy (Guthrie& Humenick, 2004). However, with the most independent reading, students do not share with one another; it is for the most part a solitary act. Interestingly, students who routinely participate in independent reading and collaborative conversations centered on reading produce significant gains in literacy(Guthrie & Humenick, 2004). Tovani(2001) writes about students, especially those struggling with reading, who fake read. For instance, when observing them they appear to turn pages and they procedurally look like readers, but they dont read. This situation is one that is connected with independent reading. However, in literature circles, each student participates so even struggling students become active participants in reading and conversation. These practices are synergistically connected as students read independently they gain knowledge of books, learn what they value in books, and enjoy the experience and with literature circles they gain the same attributes as they also participate in the social aspects of literacy.

Students like to spend time with friends. If a teacher supports collaboration through the sharing of ideas, students develop a sense of belongingness to the classroom and the other students within it(Wentzel, 2005). Literature circles allow students to talk and spend time together with a common goal or focus, that being deeper meaning of the book they are reading (Barone & Barone, 2017).

Moreover, when students learn in isolation, they form comprehension based on what they know as individuals. They see themselves as the sole developer of comprehension or understanding of a text. However, when students work together, they realize there are alternative ways of thinking and perhaps there isnt just one, correct, interpretation of text (Applebee et al., 2003). Students gather other perspectives about the text to reform or alter their original thoughts. Many times they hear something from another student that they never thought about which allows them to renegotiate meaning. Within the conversations, they have misinterpretations cleared up based on other students comments and they can provide evidence as a group to determine an appropriate meaning.

When students read the same book and share in literature circles, they can make claims about their understanding of the text, respond to and pose questions about their reading, and synthesize their understandings with other students. These thoughtful academic conversations lead to higher order and critical thinking. Students learn that they may not have a full understanding of their reading during a single reading segment. It takes continued reading and reflecting on earlier reading to develop complex understanding and appreciation for the authors skills at creating the narrative or informational text.

Hatties book (2012) focusing on

visible learning for teachers has clarified the importance of literature circles. He writes about how teachers can really influence students learning. Within his discussion, he shares that teachers need to increase the amount of time that students use and practice thinking skills and that teachers need to pay attention to how students think. Further, he argues that learning is collaborative and requires dialogue. Within this conversation, he shares that a major source of student commitment to learning comes from their peers and students. Working with peers enhances learning outcomes.

He writes about the six critical components of instruction that lead to student learning. They are: appropriate challenge that encourages students to invest in learning; designing learning situations that require student commitment to do well; having confidence that the student can achieve expectations even if they are difficult; having appropriate high expectations for student outcomes; supporting students with developing goals appropriate for learning; and having success criteria known to students. Literature circles include these components, as students are aware of expectations, knowing their teacher values their success at achieving them, and students are clearly aware of evaluation criteria.

When teachers think of grouping students, they often group students who are at the same reading level for reading groups or they group them because of a short-term learning need. However, for literature circles, students are grouped heterogeneously with approximately two students above grade level, two at grade level, and two below grade level expectations. Heterogeneous grouping allows all students, no matter their reading level, to participate in academically challenging conversations. For struggling readers, it supports them to participate in the thinking surrounding grade level materials as their reading skills improve. While not common in classrooms, grouping students of varying levels is motivating for all students and struggling students learn from the perspectives of more experienced readers(Sikorski, 2004).

Within these groups, above grade level readers are pushed and challenged because they take on leadership responsibilities as they often create questions for the group to consider and they are responsible for group management. They often provide guidance in clearing up misconceptions about text for other students and they have more challenging roles or responsibilities that support critical thinking. Oftentimes, teachers argue that these students should be pushed into more complex text because of their reading level, but within a literature circle, these students are expected to more thoroughly understand the text and share the understanding with other students. Rather than superficially exploring a more complex text, they are expected to understand the multiple nuances of meaning within grade level material. Moreover, they have choice in reading material during independent reading where they can take on above grade level material.

Students who are reading at grade level are reading materials at their instructional level and are expected to move beyond literal level comprehension. They have responsibilities or roles that nudge them beyond just a consideration of the explicit to more implicit-based interpretations. For instance, they might be asked to focus on the setting but in addition to understanding or describing what it is; they are expected to share the emotions of characters within the setting and how the setting supports these emotions. They benefit from participating in literature circles as they learn from the above grade level readers and participate and shape the groups thinking about the book and they support below grade level readers in understanding the implicit qualities of the text. Their participation clearly supports the standard expectations for grade level readers. As their thinking is pushed and they gain more sophisticated understandings of text as demonstrated in their conversations and responses, they take on higher-level responsibilities. For instance, a goal for an at grade level reader is to become a director of the group where he or she guides the group with questions and is responsible for group management.

Students who are below grade level and considered struggling readers are supported by other, more proficient readers, as they gain meaning from text. The smaller group setting allows them to participate in the thinking of more proficient readers, to engage with grade level text, and to receive support in gaining meaning from fellow students, rather than just the teacher. Typically, struggling readers work with the teacher in guided reading groups where materials are at their instructional level which is below grade level. This differentiated instruction is to support their literacy development with the goal of having students meet grade level expectations. Literature circles do not replace this differentiated instruction; rather, they are another form of instruction offered to these students. In essence, they work with materials at their current reading level while they also work with grade level material and the thinking that surrounds it. The question always is but they cant read the text with any proficiency or fluency, how can they work with grade level material. For these students, another student in the group can partner read with them or the text can be listened to on an audio recording. In these instances, students are developing listening comprehension as they participate in the conversation surrounding the book. These potential solutions are easy to bring to the classroom and do not require additional preparation or planning.

There are multiple pragmatic concerns that need to be considered before initiating literature circles. Among the concerns are choosing books, managing groups, and assigning roles.

1. Choosing books

A critical aspect of literature circles is choosing books worthy of ongoing conversation. Most of these books tend to be books that students do not generally gravitate to during independent reading. Teachers will also want to consider book length. Each group should have a book that is about the same length as the books chosen for other groups. By considering length of text, teachers can more thoughtfully plan out how long each group will take with reading, so that all groups finish at approximately the same time.

Teachers want to select current books, ones that most students are not aware of their existence, and more seasoned books that highlight theme, character development, or plot like The Giver (Lowry, 2002). Keeping current can be an issue for teachers as they are more familiar with books from their own experiences in school or have been traditionally used in their schools. For literature circles, teachers need to think carefully about book choices. In some instances, they may select books within a specific genre or by an author to help students better understand genre expectations or the authors craft. Book choice is critical to the success of literature circles and should be thought through carefully to ensure that the book is worthy of a conversation.

To become aware of possible books that might work, teachers should first meet with a school librarian. He or she can offer possible selections that would work for students. Once teachers have these recommendations, it is important for them to read each book. Teachers need to be familiar with the books before students begin reading them. When the literature circles are happening, teachers move into the groups and act as a fellow member to develop students conversations. This participation requires teachers to be familiar with the books. In order to facilitate a conversation with students about the issues in the book, it is critical for a teacher to have read the book before assigning it. So many times students are assigned a book and the teacher hasnt read it and then cannot hold a worthy conversation.

To support more ongoing knowledge of current books and books that would be exemplary in literature circles, teachers might routinely visit the following websites for information about potential books. ReadKiddoRead (www. readkiddoread.com) was developed by James Patterson. This site is routinely updated and groups books by age range. It also provides reviews of books to help with selection. Within this website are lesson plans, but with literature circles you wont need them.

Similarly, Jon Scieszka has developed a website called Guys Read(www.guysread.com) where teachers can find books that are enjoyed by boys. Books are organized by age and by topic to help with selection.

2. Managing groups

Getting each literature circle group to be well managed takes time and patience. At first, students might just share without integrating the conversation among students. Or a student might be bossy and not allow other students to participate. Or perhaps one student or a few students are not really participating. They might be flipping through their books, playing with a pencil, or whatever. It takes time and continuous teacher modeling for all students to fully participate. In other words, teachers need to explicitly teach what the expectations are within the group and continuously model and redirect.

To facilitate this process, there should be only six students in each group. A group of six allows time for each student to participate and is a reasonable size for a student to manage the group. A teacher will want to engage students in practice sessions where the teacher is clear about what good listening entails and how to keep conversation focusing on the book.

Moreover, each student is expected to have his or her responsibility completed before joining his or her literature circle. Students know that it is a privilege to participate with a group and if they are not prepared, they know they are unwelcome to join as they have nothing to contribute. Each student who is not prepared, and there are always a few occasions when this happens, reads independently and completes his or her response responsibility before joining the group. For the literature circles described here, the expectation is that students read and complete their response at home as homework. Interestingly, once students see the value of literature circles, few, if any, fail to read and respond at home in preparation for their group.

3. Assigning roles

Within each literature circle group, each student had a responsibility to complete in response to reading. These responsibilities were carefully considered for each student so that all could participate within the group and support the development of understanding. While responsibilities change to meet genre needs, more literal comprehension responsibilities are handled by below grade level groups with inferential comprehension expectations for grade level students, and critical thinking and leadership responsibilities for above grade level readers.

Following are a few of the responsibilities that help with the clarification of expectations for each member of a group. Below grade level readers might be asked to summarize the reading, illustrate the reading with a few sentences of explanation, select a passage and explain how it made a reader feel, or find interesting vocabulary words to help with understanding of the text.

At grade level readers may be asked to explain how a character feels within a setting, find facts about a time period, or explain a conflict that happened. Above grade level readers might investigate something important and necessary to understanding background information, explain why an author would include a scene, or suggest an alternative solution for a character. Above grade level readers might also be selected as a director who manages the group and develops four questions at various levels. Students identify the question as (1) or a recall question, (2) which uses information or conceptual knowledge, (3) with required reasoning and perhaps a sequence of steps to answer, and (4) with required extended thinking and perhaps no real closure or a single answer. They then use these questions within their group to support and extend conversations.

Students maintain the same responsibility throughout the entire book. By continuing with the same expectation, they are able to develop it and really use it to extend thinking about the book. When new groups are formed, students may have a new responsibility or they may continue with the previous one. These decisions are made by the teacher to best support meaning-making within the literature circles and to support specific learning targets for individual students.

Following are some of the potential roles or responsibilities a student may have during a literature circle. Importantly, a student maintains the role or responsibility throughout the entire reading of the book and each student in the group has a different responsibility. The teacher determines how much of the book will be read each day so that most books are completed within three or four weeks to maintain students interest.

(1) Illustrator

The Illustrator sketches three images of the main events that happened during their reading. Once the sketch is completed, he or she writes one to three sentences explaining each of the sketches.

(2) Summarizer

The Summarizer writes a short paragraph summarizing the main events. Students are expected to also write the events in chronological order.

(3) Passage Picker

The Passage Picker chooses a passage that impacted him or her, in other words, made them stop and think and feel about what was shared. Once the passage is selected, he or she writes about what feelings it generated. Following is an example from Holes (Sachar, 2000):

“This passage on page 207 made me feel challenged and scared. It made me feel challenged because a policeman said, ‘If you were a survivalist you would survive the rainstorm. Like a man is telling you to go out there and survive that rainstorm. It made me feel scared because a police officer is telling you to go outside and survive when you could die from a thunderbolt. And a policeman is supposed to keep you safe but he is telling you that if you are tough, you would walk through a tornado even if you would die. How did this passage make you feel?”

This role moves students from just reporting to including emotional qualities that lead to interpretation.

(4) Vocabulary Finder / Word Wizard / Interpreter

The Vocabulary Finder locates 2 or 3 words that are unknown to him or her and provides a definition of each word and what that word means in context. Following is an example of one word a student chose and how she used examples from the book to further explain the word:

Scrambling.

“Raven had to retouch Dereks makeup.”

“The director checked the angle of the three cameras.”

“The assistants adjusted the lighting.”

These are 3 examples from the book showing scrambling. It means they had to think fast to find a solution.

More than just describing a word, this role asks students to find examples, describe the meaning of the word and keep both of these tasks grounded in the text.

(5) Travel Tracer

The Travel Tracer identifies a character within a setting. The student would describe each setting of the reading in detail and explain the emotions of the characters in each setting. Also, the student would then explain why the characters felt the way they did. Following is an example from Holes:

“In this setting, the character felt lucky. I think he felt lucky because while he was digging, he found something like a heart and he saw it said KB. He was thinking of giving it to X-ray and he was thinking of keeping it too.”

The Travel Tracer asks students to pay attention to a setting and how it contributes to the meaning through the characters emotions. Rather than just describing a setting, students are pushed to connect it emotionally.

(6) Fact Finder

The Fact Finder finds interesting information from the story. This job is used mainly when students were reading historical fiction. They research important facts that support the time period such as an artifact, an event, or vocabularies relating to this time period. This person adds to the background information necessary for understanding. Following is an example of this role:

“I found out that a cassette is a video made on magnetic tape that can be played.”

“From page 77 it said that Noahs moms friend came over with a cassette.”

This expectation helps all students understand interesting tidbits of information that contributed to overall meaning.

(7) Character Trait Finder

The Character Trait Finder chooses a character and explains a trait he or she portrays. The students are expected to find text evidence to support this trait such as how characters acted or what they said. Following is an example from Sydney when she was reading The Giver.

“Jonas is a planner and he is brave. In my reading, Jonas was making a plan to escape. He made the plan because the community must change. He is worried about his plan though it will change everything. He begs the Giver to come with him, but the Giver has to stay because he is too weak to leave.”

This role pushes students to really investigate characters traits and to support them using text evidence and how they are revealed within a story. They must find examples to support their interpretations.

(8) Conflict Finder

The Conflict Finder locates a conflict within their reading and he or she identifies the type of conflict. They can identify external or internal conflict and what type of conflict (character vs. character, character vs. nature, character vs. self, or character vs. society). After identifying the conflict, the student then explains what was happening and why there was conflict with that character. An example comes from Chance who wrote about Jonas internal conflict within The Giver. He wrote:

“Jonas is truly alone now. For a couple of days, the Giver and Jonas have been planning and Jonas has been receiving the most brave and courageous memories. But, Jonas really wants the Giver to come. Jonas has to stay strong but the journey might break him.”

Rather than just describing a character, this role expects students to discover conflict within their reading and to provide examples of the conflict and identify what kind of conflict is displayed.

(9) Investigator

The Investigator finds an idea or noun that is confusing. He or she researches it and then explains what it means in text. Students are asked to provide a picture to allow the other group members to see what they have investigated. Again, this role is about researching an idea or concept as opposed to a vocabulary or unknown word. Gigi wrote about Nat King Cole as she was confused about who he was when his name showed up in her reading. She wrote:

“My word or person is Nat King Cole. He was born in March, 1919 in Montgomery, Alabama and he died in 1965 from cancer. He was a singer and he had a soft voice. He was the first African American to host a TV show. When I went back and read page 59, I understood that Fern and Miss Patty Cake were like that Nat King Cole song Unforgettable. Now I know how Nat King Cole helps me understand these characters. ”

The investigator roles can build background knowledge or help with understanding academic vocabulary. The important aspect is that students have to bring this information back to an understanding of text.

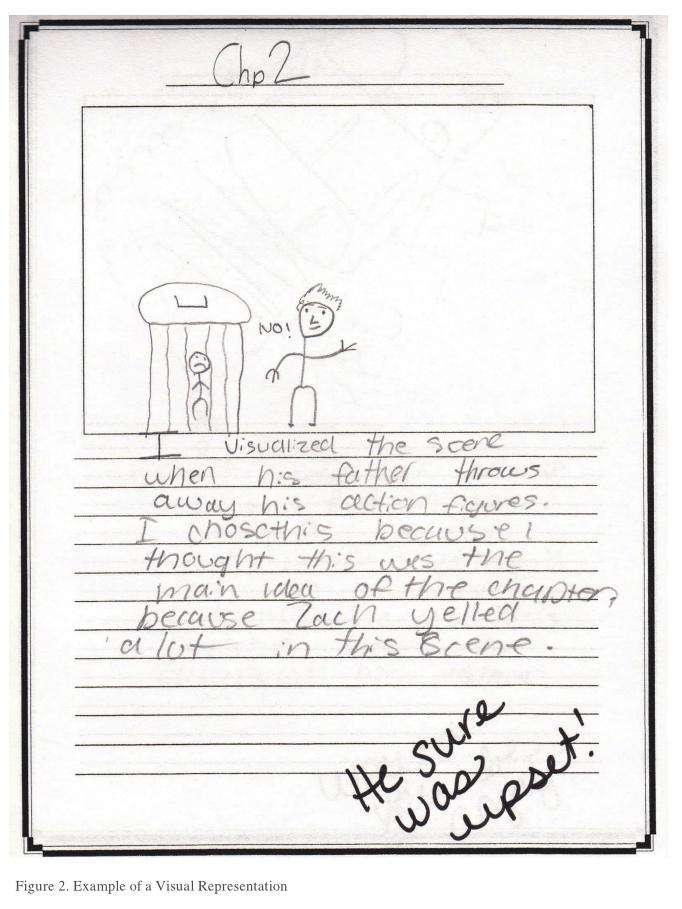

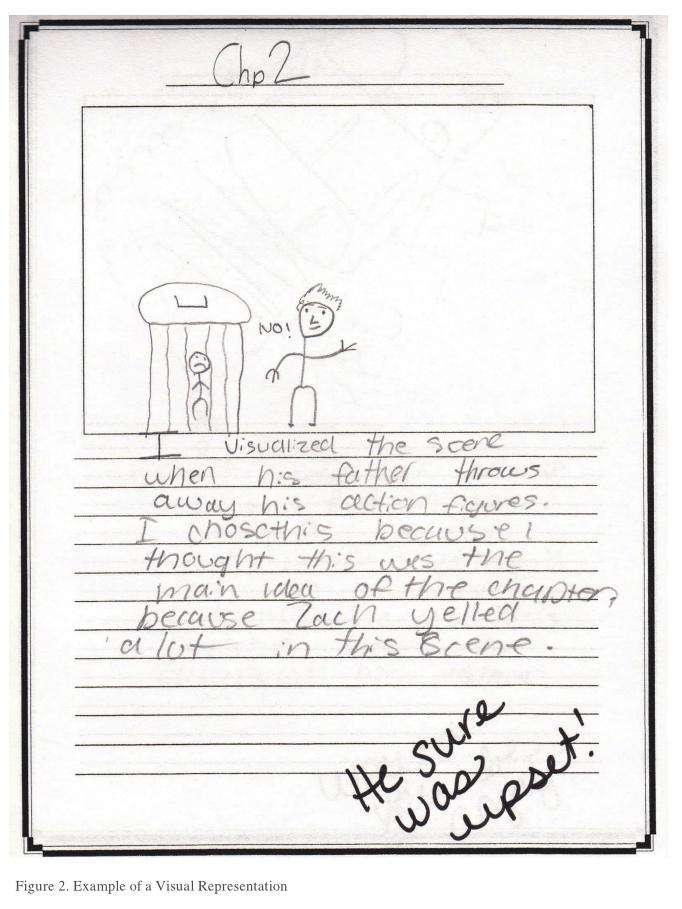

(10) Visual Viewer

The Visual Viewer allowed students to create a mental image of something they visualized during their reading. After they created the visualization, they also needed to explain in words why they visualized it. Students could visualize using an illustration, words, graffiti, a slogan, or anything else they came up with in their mind to reflect the reading(see Figure 2).

(11) Journaler

The Journaler selects an important scene and explains why the author would include it or why this scene is important to the story. Students can answer questions such as: Why did the author include this scene? Does the character make an important choice in this scene? Does the scene illustrate a character trait? Did the character face conflict, resolution, or a change? Did the author reveal something the reader must know? An example of a Journaler response comes from Taylor. She wrote:

“The author included this scene because he wanted the two different stories to collide for a second or two, it allowed for the main characters to meet.”

Within this role, students determine the authors purpose of including a scene and how it contributes to meaning.

(12) Solution Suggester

The Solution Suggester explains the way a character solves a problem from the book. Included in this explanation are what the problem is, how the character solves the problem, and what challenges they face when solving the problem. After the problem is defined, the student provides an alternative solution and predicts how this new solution would change the story. An example comes from Macy as she was reading Holes:

“Problem—Mr. Sir argues about his sunflower seeds to the warden, but she poisons him with snake venom.

“Solution—Mr. Sir explains to the warden that he doesnt think that Stanley stole the sunflower seeds.

“Alternative Solution—Mr. Sir could not mention the sunflower seeds to the warden.

“Effect—Mr. Sir would not be poisoned by venom and would still be alive.”

This role pushes students to consider the plot and how minor changes can result in major shifts in outcomes. It also allows for critical thinking when determining what might happen to the characters if they chose their solution over the one the author wrote.

(13) Director

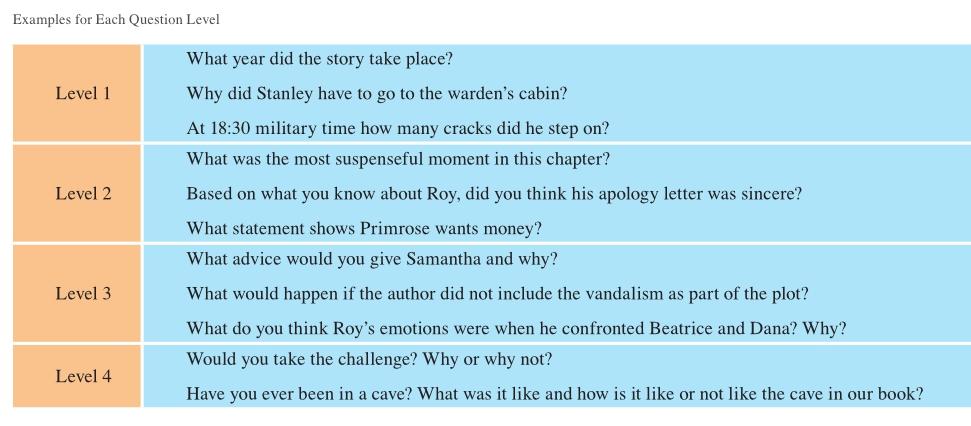

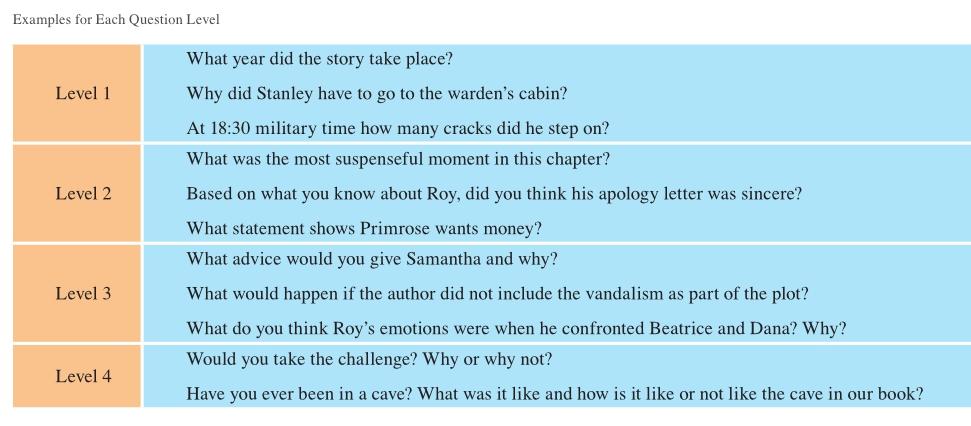

The Director creates five questions of varying QAR levels to share with his or her group. The QAR levels are Level 1, the answer is right in the text with a single correct answer; Level 2, you must think and search for the answer and it could be in more than one, single location, the answer is also right in the text; Level 3, where the answer requires inferences based on the text using evidence from the text to support the answer; and Level 4, where answers are crafted with both text and personal opinions. The Table above shows the examples for each question level.

These roles encompass the majority of generic roles that serve fiction primarily and some support informational text. Each task contributes to an overall understanding of text and as students continue reading a text offers possibilities for new interpretations.

There is no Connector role as this role led students away from text rather than to it. Often when the Connector role was included, it was difficult to recognize conversation related to the book. More often than not, one student shared a story, then another, until each student shared. Rarely, students bring these connections back to text.

Teachers can also use non-fiction in literature circles. For non-fiction, roles may be altered a bit to match the expectations of this type of text. For instance, there may be a Nonfiction Fact Finder. Following is an example:

Your job is to find 3 facts that you learned from the reading. Explain why and how these facts have impacted the topic you are reading about.

Fact 1:

Impact:

Goliath was a Philistine warrior defeated by David, King of Israel. Goliath could breathe fire and was 10 times bigger than David. This impacts our book because the citys belief in the giants in the Bible led them to Goliath. I learned that Goliath said to the people to choose someone to defeat me and my army will be yours. They chose David to cut off Goliaths head. All this information about Goliath is important because they thought the ranch was built over the spot where Goliath was slain. They also said they found a silver blade there and they thought it possibly could have been the murder weapon. Now here comes the problem. Goliath was in Israel and the giant was in Syracuse, New York. The giant was also 10 feet 4 but Goliath was 9 feet 4 which simply leads to the conclusion that the Cardiff giant wasnt Goliath.

(14) Inventor

Another role might be the Inventor. In this role, the student creates a response using a text feature like a graph, chart, diagram, picture with caption, and so on. Figure 3 shares an example of an Inventors response using a picture and caption.

Closing

Reading Aloud, Independent Reading, and Instructional Strategies like Literature Circles support student comprehension. In Reading Aloud, teachers support students in understanding text that is just beyond their ability to read independently. In Independent Reading, students become engaged with the act of reading and find genres and authors that appeal to them. In Literature Circles, students socially engage with reading and developing understanding of text. Each of these elements supports teachers and students in creating meaning from reading.

References

Allington, R. & McGill-Franzen, A. 2003. The Impact of Summer Loss on the Reading Achievement Gap[J]. Phi Delta Kappan, 85 (6): 68-75

Anderson, R., Hiebert, E., Scott, J., et al. 1985. Becoming a Nation of Readers[M]. Washington, DC: National Institute of Education.

Applebee, A., Langer, J., Nystrand, M., et al. 2003. Discussion-Based Approaches to Developing Understanding: Classroom Instruction and Student Performance in Middle and High School English[J]. American Educational Research Journal, (40): 685-730

Bandré, P., Colabucci, L., Parsons, L., et al. 2007. Read-Alouds Worth Remembering[J]. Language Arts, (84): 293-299

Barone, D. & Barone, R. 2016. Are You a Reader? Elementary Students Respond[J]. Kappan, 98(2): 47-51

Barone, D. & Barone, R. 2016. Literary Conversations in the Classroom: Deepening Understanding of Nonfiction and Narrative[M]. New York: Teachers College Press.

Barone, D. & Barone, R. 2017. “I Never Thought I Would Read This Much”: Becoming a Reader[J]. The Educational Forum, 82(1): 21-39

Barone, D. & Xu, S. 2008. Literacy Instruction for English Language Learners Pre-K-2[M]. New York: Guilford.

Barone, D. & Youngs, S. 2008a. Your Core Reading Program and Childrens Literature K-3 [M]. New York: Scholastic.

Barone, D. & Youngs, S. 2008b. Your Core Reading Program and Childrens Literature 4-6 [M]. New York: Scholastic.

Brenner, D., Hiebert, E. & Tompkins, R. 2009. How Much and What Are Third Graders Reading?: Reading in Core Programs[C]// Hiebert E. (Ed.). Reading More, Reading Better. New York: Guilford: 118-140

Butler, D. 1975. Cushla and Her Books[M]. Boston: The Horn Book, Inc.

Cochran-Smith, M. 1984. The Making of a Reader[M]. Norwood, NJ: Ablex Publishing Corporation.

Cooper, P. 2009. Children Literature for Reading Strategy Instruction: Innovation or Interference?[J]. Language Arts, (86): 178-187

Esquith, R. 2007. Teach like Your Hairs on Fire[M]. New York: Penguin Books.

Fox, M. 2008. Reading Magic: Why Reading Aloud to Our Children Will Change Their Lives Forever[M]. New York: Harcourt.

Gambrell, L. 1984. How Much Time Do Children Spend Reading During TeacherDirected Reading Instruction?[C]// Niles, J. & Harris, L. (Eds.). Changing Perspective in Research in Reading/ Language Processing and Instruction. Rochester, NY: National Reading Conference: 193-198

Gambrell, L. 1996. Creating Classroom Cultures that Foster Reading Motivation[J]. The Reading Teacher, (50): 14-25

Sikorski, M. 2004. Inside Mrs. OHaras Classroom[C]// Guthrie, J., Wigfield, A. & Perencevich, K(Eds.). Motivating Reading Comprehension: ConceptOriented Reading Instruction. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum: 195-223

Sumara, D. 2002. Why Reading Literature in School Still Matters[M]. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Tompkins, G. 2010. Literacy for the 21st Century: A Balanced Approach (5th Edition) [M]. Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

Tovani, C. 2001. I Read It, But I Dont Get It: Comprehension Strategies for Adolescent Readers[M]. Portland, ME: Stenhouse.

Trelease, J. 2006. The Read-Aloud Handbook[M]. New York: Penguin Books.

Tunnell, M. & Jacobs, J. 2008. Childrens Literature, Briefly (4th Edition)[M]. New York: Pearson.

U.S. Department of Education. 2005. NAEP 2004 Trends in Academic Progress: Three Decades of Student Performance in Reading and Mathematics[M]. Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics.

Wentzel, K. 2005. Peer Relationships, Motivation, and Academic Performance at School. In A. Eliot & C. Dweck(Eds.). Handbook of Competence and Motivation. San Diego, CA: Academic Press: 279-296

Wilhelm, J. 2008. “You Gotta Be the Book”: Teaching Engaged and Reflective Reading with Adolescents[M]. New York: Teachers College Press and Urbana, IL: National Council of Teachers of English.

White, D. 1956. Books Before 5[M]. New York: Oxford University Press.

Wolf, S. 2004. Interpreting Literature with Children[M]. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Wolf, S. & Heath, S. 1992. The Braid of Literature: Childrens Worlds of Reading[M]. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.