Original article Group dynamicsmotivation to increaseexerciseintensity with a virtual partner

Stephen Smeninger *,Christopher R.Hill Norert L.Kerr ,Brin Winn ,Alison EeJmes M.Pivrnik Lori Ploutz-Snyer ,Deorh L.Feltz

aDepartment of Kinesiology,Michigan State University,East Lansing,MI48824,USA

b Department of Psychology,Michigan State University,East Lansing,MI 48824,USA

c Department of Media and Information,Collegeof Communication Arts&Sciences,Michigan State University,East Lansing,MI 48824,USA

d NASAJohnson Space Center,Universities Space Research Association,Houston,TX 77058,USA

Abstract Background:The effect of the K¨ohler group dynamics paradigm(i.e.,working together with a more capable partner where one's performance is indispensable to the team outcome)has been shown to increasemotivation to exercise longer at astrength task in partnered exercise video games(exergames)using asoftware-generated partner(SGP).However,theeffect on exerciseintensity with an SGPhasnot been investigated.Thepurpose of this study was to examine the motivation to maintain or increase exercise intensity among healthy,physically active middle-aged adults using an SGPin an aerobic exergame.Methods:Participants(n=85,mean age=44.9 years)exercised with an SGPin a6-day cycleergometer protocol,randomly assigned to either(a)no partner control,(b)superior SGPwho wasnot a teammate,or(c)superior SGPasateammate(team scorewasdependent on theinferior member).Theprotocol alternated between 30-min continuousand 4-min interval high-intensity session days,during which participantscould change cyclepower output(watts)from target intensity to alter distanceand speed.Results:Mean change in wattsfrom a targeted intensity(75%and 90%maximum heart rate)wasthe primary dependent variable ref lecting motivational effort.Increases in performance over baseline were demonstrated without signif icant differences between conditions.Self-eff icacy and enjoyment weresignif icantly related to effort in themoreintenseinterval sessions.Conclusion:Under these conditions,no K¨ohler effect was observed.Exercise performance during the higher-intensity interval format is more closely related to enjoyment and self-eff icacy beliefscompared to thecontinuoussessions.2095-2546/©2019 Published by Elsevier B.V.on behalf of Shanghai University of Sport.This isan open accessarticleunder the CCBY-NC-ND license.(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

Keywords:Exerciseintensity;K¨ohler effect;Motivation;Software-generated partner

1.Introduction

The majority of Americans fail to exercise at levels shown to increase f itness and reduce health risk,1,2falling short of the 150 min/week of moderate-intensity physical activity(PA)required to meet the Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans(PAG).3Among the various approaches being explored to motivate adults to increase PA,there is evidence that exercising in a group setting or with exercise companions can increase time engaged in regular PA.4,5Simply performing in the presence of another group member may have a positive(or negative)effect on one's performance.6However,considerable laboratory research on motivation in task groupshassuggested that certain types of interdependence among group members can lead to a signif icantly increased level of effort and motivation gains(i.e.,versusworking individually).These motivation gains stand in contrast to work focused on preventing the adverse group effects of social loaf ing,in which a group member exertslesseffort than would beexpected by his or her individual performance.7,8A well-studied and particularly robust motivation group dynamic,the K¨ohler effect,9,10capitalizes on group member interdependence to motivate greater effort in taxing physical performance of lower-ability group members.K¨ohler11noted that weaker membersof dyads could perform a taxing physical task(viz.,yoked biceps curls)longer than onewould expect from their individual performances.The dyads in K¨ohler's experiments were functionally linked during the task(i.e.,yoked)so that once the weaker member was exhausted and quit,the stronger member was forced to quit as well.This interdependent arrangement,in which the weaker member determines the potential group productivity,is referred to as a conjunctive task demand.12The conjunctive task condition stresses the indispensability of a weaker member's efforts for his or her team;motivation is likely to beenhanced when theperson seeshisor her effortsas being highly instrumental in achieving team success.13The K¨ohler effect also occurs when low-ability group members increase their motivation as a result of upward social comparison14with their more capable group members.13Furthermore,prior research has shown the motivation to increase effort is most pronounced when the weaker member perceives a moderate difference in ability,so that the partner is not too similar or too superior.15

It should be noted that motivation cannot be observed directly and must beinferred.Researchersmeasuremotivation in numerous ways,including the use of behavioral representations and self-reports.These behaviors represent one's conscious or nonconscious self-regulation and decision making related to attaining a desired goal.Researchers studying the K¨ohler effect use behavior,in terms of performance effort at simple tasks,to infer motivation.As Tour′e-Tillery and Fishbach16note,“Measuressuch aschoice,speed,performance,or persistence exerted in the course of goal pursuit capture the goal congruence of behavior and can thus assess the strength of one'smotivation to pursuethegoal”.

A 2007 meta-analysis reported a large effect size for the K¨ohler motivation gain across many studies.17More recent research has explored the K¨ohler motivation gain effect in exercise settings.18-20This series of studies used simple muscular persistence tasks(e.g.,abdominal plank exercises)and aerobic cycleergometer protocolswhileparticipantsinteracted with a human partner presented to them through an Internet connection.Depending on the protocol,a video screen served to project images of the participant exercising,clips of a trainer demonstrating the exercises,and the partner exercising.Whether the protocols were single-or multiple-session exercise regimens,participants demonstrated signif icant motivation gains in exercise persistence in support of the K¨ohler effect group dynamic.

While researchers continue to test the boundaries of the K¨ohler effect on exercise persistence,none have sought to apply the successful motivation paradigm to study increasing the intensity of exercise under high-intensity aerobic conditions(>80%of maximum heart rate(HRmax)).21Those engaging in PA must attain at least a moderate-to-vigorous level of intensity to benef it f itness and health.3Among active adults,shorter-duration,higher-intensity exerciseisoften used(i.e.,at least 75 min/week of vigorous-intensity aerobic PA,or an equivalent combination of moderate-and vigorous-intensity aerobic activity)as an accepted alternative to meet the PAG.3In fact,high-intensity interval training(HIIT)has become an increasingly popular method of satisfying recommended levels of PA.21HIIT usually involves brief,intense burstsof activity,alternating with periods of recovery or active recovery(movement at a low intensity or 40%-50%of HRmax21).Evidence that HIIT is effective in improving health for nondiseased adults and adults suffering from cardiometabolic disease22,23hashelped fuel the trend for shorter,but moreintense,exercise protocols.As the intensity of exercise increases,inherent diff iculties and discomfort may result in motivation challenges to continue the exercise or challenges to achieve the intended workout levels.Although there is evidence to suggest that high-intensity interval and vigorous aerobic exercise may not be intimidating for most activeadults,24researchershave demonstrated that higher intensitiesmay have anegativeimpact on adherence,reported exertion,and affect in less-active adults.25,26Therefore,it isworth exploring whether the K¨ohler motivation gain effect may help adults reach the necessary intensity levels to ensure that the health-related goals of exercise aremet.

Unfortunately,despite recognized motivation gains in group settings,exercising with apartner or group posessignif icant challenges.Locating and coordinating time to exercise with one or more partners,even with sessions of shorter duration,is not always easy to do and adds a hurdle in achieving consistent workouts.More importantly,ability discrepancies between desired partners may not be optimal or f luctuate session to session.Exercising with a software-generated partner(SGP)may provide a practical way to control for such problems inherent with traditional human workout partners.Using SGPs in a K¨ohler motivation paradigm affords the opportunity to adapt the necessary experimental design as this research line moves forward toward practical applications.Of course,to benef it from an SGPduring exercise,onewould berequired to accept,to some extent,the non-human partner as if he or she wasreal.

According to the Media Equation concept,people often interact with media similarly to human interpersonal interactions.27Nass and colleagues28found that computers are often recognized as“social actors”.In other words,people respond socially to human-like characteristics of computers and apply social rules to their interactions when doing so.29,30Recent studies have successfully used SGPs in exercise-persistence tasks.31-33Not only did the participants rate the exercise SGPs positively in terms of likability and anthropomorphic features,but the motivation gain across these sequential studies also demonstrated moderate effect sizes(Feltz et al.,31d=0.57;Samendinger et al.,33d=0.76).These effects were similar in magnitude to those previously reported to be observed with human partners during conjunctive task groups(g=0.72).17Such f indings suggest adult exercisers can be motivated by an SGPto exercise longer in their sessions.

Self-eff icacy is another key variable to consider in the study of exercise performance because one's beliefs about successfully completing a task have been shown to be a signif icant predictor.34,35Depending on feedback from sources of one's self-eff icacy(e.g.,mastery experiences,vicarious experiences), people with higher levels of self-eff icacy will often set more challenging performance goalsand persist in challenging situations longer than individuals with lower-eff icacy beliefs.These challenging goals create a performance discrepancy that can motivate behavior.Bandura36recognized that not only does one's self-eff icacy help to determine new performance goals,but mastery experiences may also alter one's self-eff icacy in a reciprocal relationship.Increasing PA,in general,can be the focus of this goal-directed process,but it can also be specif ic to the persistence or intensity of such behavior.

The purpose of thisstudy wasto examine the K¨ohler group dynamics paradigm on the motivation to maintain or increase exercise intensity with middle-aged active adults,aswell asto explore the association of self-eff icacy and enjoyment with performance.An SGP embedded in a simple exergame video display wasused to manipulate the psychological mechanisms of social comparison and team indispensability that have consistently produced the K¨ohler effect.This study is signif icant becauseif an SGPwithin the K¨ohler group dynamicsparadigm can enhance high-intensity exercise training,while also being self-eff icaciousand enjoyable,it can open up a powerful set of new toolsin exercise video-game design for f itness,especially for those with social physique anxiety,those who lack the time or resources to join an exercise group,and those in exerciserehabilitation therapies.Thef irst hypothesiswasthat exercise effort would be greater with a more capable coacting SGP(i.e.,exercising alongside an SGP but not linked in a team)than when exercising alone because of the effects of a social comparison mechanism.The second hypothesis was that exercising with a moderately more capable SGP teammate under conjunctive task would lead to the highest gains in performance(because of the additional effect of the indispensability of one'sefforts).

2.Methods

2.1.Participants

Participants were male and female physically active community members,30-62 years of age,who were able to engage in vigorous PA(n=85,49 females).Participants were recruited through community advertisements and solicitation of community athletic organizations(e.g.,running and cycling clubs).Advertisementstargeted regular exercisersand athletes(runners,swimmers,triathletes,or others)but excluded individuals who solely compete in competitive cycling events.A physician's consent to participate was required for all men older than 44 years of age,women older than 55 years,and for any others determined to be at risk after screening(using the Physical Activity Readiness Questionnaire).To qualify for participation,potential participants were given an incremental exercise test to exhaustion(cycle ergometer)to estimate their aerobic capacities(VO2max).Participants were required to achieve the 150-W stage of the test(for a steady-state 1.5 min),a general level of f itnessconsidered by the study'sexercise physiologistssuff icient to participatein an intenseaerobic exercise protocol.A total of 6 participants either self-selected out of the study after the incremental exercise test or did not qualify and therefore were not included in the sample.Qualif ied enrollees were given USD36(USD6 per visit)for their participation at theend of thestudy.All participantscompleted the informed consent process before participation.The study was approved by the Michigan State University's Institutional Review Board.

2.2.Procedures

The protocol consisted of alternating continuous30-min vigorous aerobic exercise sessions and high-intensity interval sessions over 6 days.To compare the effects of the K¨ohler group dynamic on participant exerciseintensity,participantswererandomly assigned to an individual control(IC)condition or to one of two SGP conditions:as a coacting partner(COAP)or as a teammate in a conjunctive group(CONJ)task structure(i.e.,working toward a team score dependent on the weaker member).In both partnered conditions,the SGPwasprogrammed to ride moderately faster than the participant and would always appear ahead of him or her on thevideo monitor.

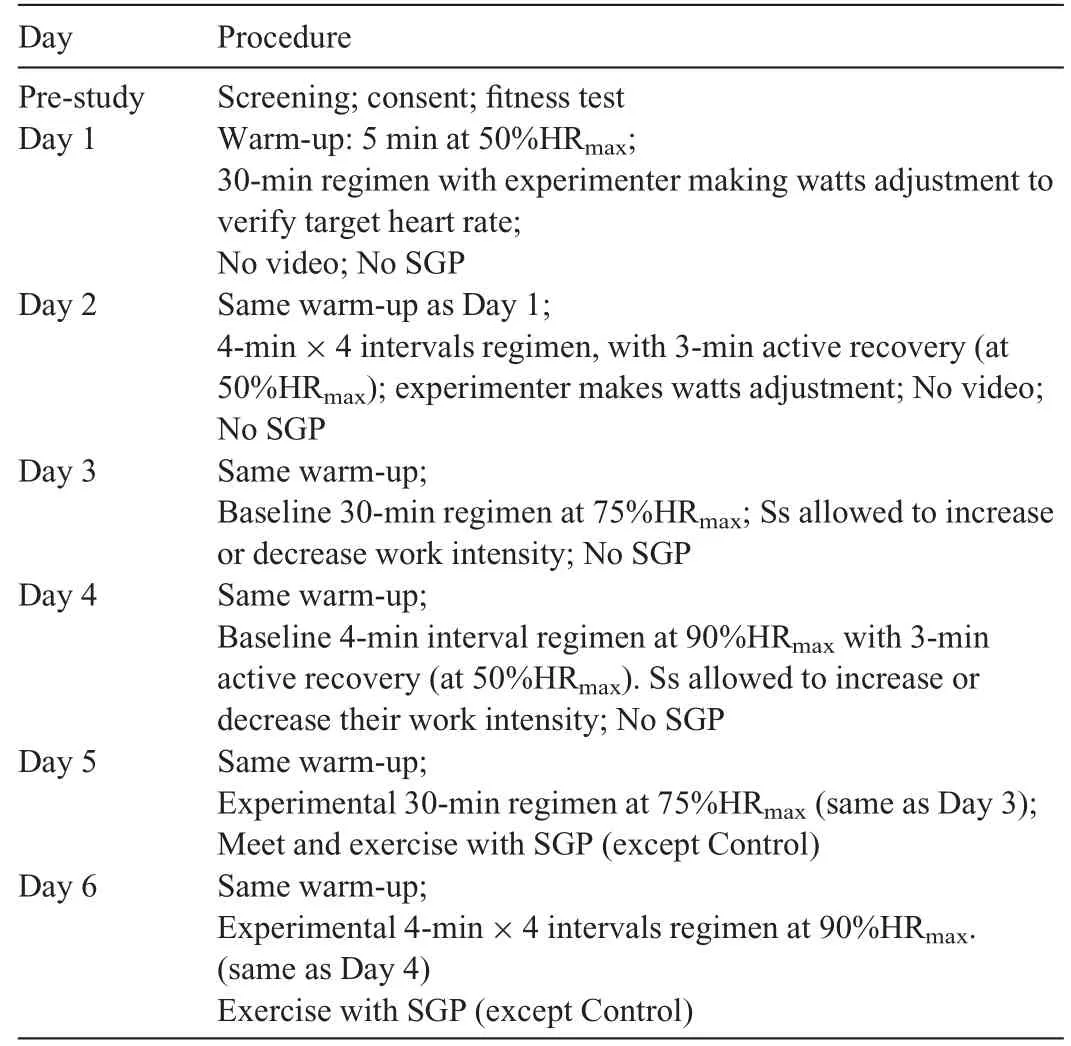

Participants completed the 6 workout sessions on a cycle ergometer(Monark LC4;Monark Exercise AB,Vansbro,Sweden),alternating between 2 protocols:30-min continuous cycling with the preset wattage at 75%of his or her estimated HRmaxand a 4×4-min interval workout at 90%HRmax(i.e.,4 intervals lasting 4 min each,with 3 min of active recovery between intervals).Results from the initial qualifying maximal exertion test were used in regression equations to estimate the 75%and 90%of HRmaxvalues required for the workout sessions.The workout protocol was taken from the National Aeronautics and Space Administration's(NASA)aerobic training program.37In both the 30-min and 4-min interval workouts,participants could increaseor decreasethewattageon a keypad.On Days1 and 2,participants cycled with the game screen turned away as the research assistant adjusted the cycle wattage up or down to ensure that participants were working at the prescribed heartrate.On Days 3 and 4,participants cycled viewing the virtual track without a partner,regardless of experimental condition.On Days 5 and 6,participants cycled with an SGP(except in the IC condition)on the same tracks as Days 3 and 4.The virtual track was f lat without surface inclines or declines(Table1).

CONJand COAPconditionswere visually identical to participants,with instructions and experimental manipulations differing between conditions.From Day 3 onward,participants were provided veridical feedback about their power output(in watts),distance,and revolutions per minute(RPMs).In the experimental conditions,after the workout on Day 4,participantsweretold they would beworking with an SGP.Thepresence of the workout SGP and experimental manipulations were explained to the participantsby asame-sex virtual trainer just before the Day 5 workout.These manipulations included being told that the SGP(coactor or teammate)was programmed to be somewhat more capable than the participant but with f inite stamina and the potential to fatigue like any other exerciser.In the COAP condition,participants were informed that they could observe the SGP on the screen but would be exercising independently from each other and would receive individual performance feedback.In the CONJcondition,the trainer introduced the SGP as a teammate,yoked together so that neither would be ableto cycletoo far ahead or too far behind.The trainer also explained that the team outcomedepended on theteam member who cycled thelesser distance(distance was controlled by the intensity of cycling chosen by each participant by pushing buttons on a keypad).The game software was programmed to always represent distanceasaconsistent and direct linear representation of theparticipant-chosen intensity.

Table1Experimental protocol.

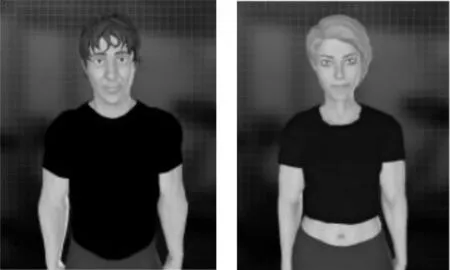

When returning on Day 5,participants were introduced to a same-sex SGP,who was created to appear to be comparable in age(Fig.1),and exchanged agreeting and somebasic personal information(“your name,whereyou'refrom,something about yourself”).No other interaction occurred during the 2 partnered sessions.In the partnered conditions,the participant and the SGP always began at the same pace,but the SGP soon moved out in front and kept a moderate lead of about 10 feet throughout the entirety of the workout.Despite any acceleration or change in pace by the participant,the SGP's moderate lead was always maintained.This distance was chosen to represent a moderate ability difference without being discouraging to the participant.To maintain the experimental cover story and observeany potential motivation gain effect,theparticipantswerenot told until adebrief ing that they would never be able to pass the SGPregardless of how high they increased the intensity of the workout.

2.3.Measures

2.3.1.Effort

Primary measures of performance effort(the inferred measure of motivation)were based on mean power workload(in watts)collected during each session and recorded in the software output.Mean power was calculated from each participant's response to instructions to press a green button to increase intensity(and distance covered)or press a red button to decrease bike intensity(as one might do when selecting a bike gear).Participants were informed that simply pedaling faster or slower would not affect the intensity or distance covered.This experimental feature isolated the inferred motivation measure to whether the participant purposively selected the button.During the 4×4-min interval sessions,average power output was calculated without the four 3-min active recovery periods between intervals.The primary measure of performance was the difference in session mean power output in watts from the session pre-programmed beginning watts(i.e.,watt difference)throughout the trial(averaged across time).This measure represented the motivation participants acted on to increase watts above the baseline set for them at 75%or 90%of their HRmax.

2.3.2.Self-eff icacy

Self-eff icacy was measured each pre-and post-session following Bandura's guidelines36and was based on measures used in previous K¨ohler effect experiments in exercise settings.19The stem of the question on continuous exercise days for each pre-session read,“Rate your conf idence that you can cycle for 30 min at the following intensities.”The stem of the question for post-sessionswassimilar except that it referred to“thenext timeyou do thisworkout”.Theinterval days'presession self-eff icacy question stem read,“Rate your conf idence that you can cycle for all four 4-min intervals at the following intensities”.The stem of the 4-min postsession question was similarly phrased to ref lect“the next time”the participant completes this workout.Self-eff icacy for each level of intensity increased 5%on the scale items until participants rated their beliefs at 100%intensity,beginning at 75%for the continuoussessionsand 90%for theinterval sessions.Participants rated their conf idence on a scale of 0(not conf ident at all)to 10(completely conf ident).The responses for each session type are averaged across the different levels of intensity for a mean value for self-eff icacy beliefs.

Fig.1.Maleand femalesoftware-generated partners.

2.3.3.Enjoyment

To further explore factors that may play a role in participants'performance,enjoyment was measured on each day after exercise using a 5-item modif ied Physical Activity Enjoyment Scale(PACES).38Each item wasrated on a 3-point bipolar scale(e.g.,1=Ienjoy it;3=Ihate it).The stem of the PACES questionnaire read:“Please rate how you currently feel about the PA you have been doing according to the following scales.”The authorsof the scale reported adequate factorial validity and invariance over time for the revised measureacrosstwo independent samples.

2.3.4.Partner and teamperceptions

For participantsin thepartnered conditions(COAP,CONJ),questionnaires were provided to assess their perception of the partner relationship or partner dynamics.On Day 5(the day participantsmet the SGPfor thef irst time),they completed the Alternative Godspeed Indices,39a 19-item semantic differential survey with 3 subscales:humanness(e.g.,artif icial vs.natural),eeriness(e.g.,bland vs.uncanny),and attractiveness(e.g.,repulsive vs.agreeable).This questionnaire attempts to capture the participants'emotional responses to the SGP.Day 6 questionnaires assessed social-and task-related responses to working with an SGP.Participants'feelings toward their partner were surveyed using 4 items on a 5-point rating scale(e.g.,“I liked my partner”,“I felt comfortable with my partner”).Exercise team perceptions(5 items,e.g.,“I felt Iwas part of a team”,“Ithought of my partner as a teammate”)were collected using a 9-point scale.30Group identif ication was measured using 6 items(e.g.,“I considered this exercise group to be important”,“Iidentif ied with thisexercise group”)on aresponsescaleranging from 1(strongly disagree)to 5(strongly agree).

2.4.Statistical analysis

Power analyses(performed using G*Power software40)indicated that a total sample size of 66 participants(3 groups,2 measurement points)would be suff icient to obtain amedium effect size of 0.50 with a power of 0.95 and anαlevel of 0.05.Data for changes in exercise intensity were evaluated with repeated measures of analysis of variance(RM ANOVA)to examine the effects of treatment(condition type)and day of session for both the 4-min sessions and the continuous sessions.Multiple regression analysis was used to test relationships between pre-exercise self-eff icacy,enjoyment,and performance effort.t tests were used to test the social and task-related perceptions of working with an SGPbetween the experimental conditions(COAP and CONJ).All analyses were conducted using IBM SPSSStatistics Version 22.0(IBM Corp.,Armonk,NY,USA).

3.Results

3.1.Preliminary analyses

Primary attention was given to motivation measures of effort intensity in terms of cycle ergometer watt difference(e.g.,mean difference throughout the trial,averaged across time,from initial“programmed”wattsversus mean watts during thecontinuousand interval sessions).

No condition differences were noted for age(44.9±9.5 years,mean±SD),F(2,83)=0.28,p=0.78;body mass index(25.3±4.9 kg/m2),F(2,83)=0.38,p=0.69 or for self-reports of prior typical moderate or vigorous PA:F(2,82)=0.97,p=0.38;F(2,83)=0.05,p=0.95.Furthermore,there were no noted condition differences in f itness(initial qualifying submax test calculated target watts)between the groups for the 75%of HRmaxand 90%of HRmaxvalues:F(2,84)=1.10,p=0.35;F(2,84)=1.30,p=0.26.

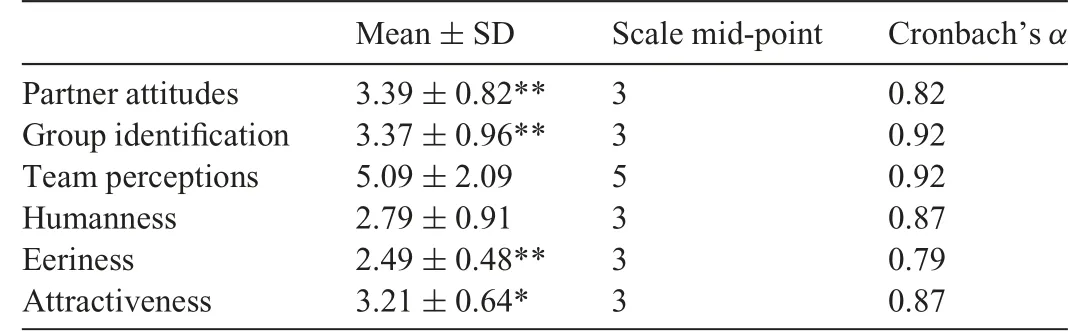

For experimental conditions(COAPand CONJ),social-and task-related perceptions of working with an SGP during an exercise protocol were assessed with multiple variables,including attitudes toward the partner,perceptions of working in a group and team,and indices of humanness,eeriness,and attractiveness.No signif icant differences were noted between the CONJ and COAP conditions for any of the relationship variables.

Results indicated that participants in both conditions held favorable attitudes toward the SGP,felt part of a group,and perceived the partner asattractive but not eerie(Table 2).Participant perceptions were neutral in regard to feelingsof being part of a team and ratingsof the SGP'shumanness.

3.2.Primary analyses

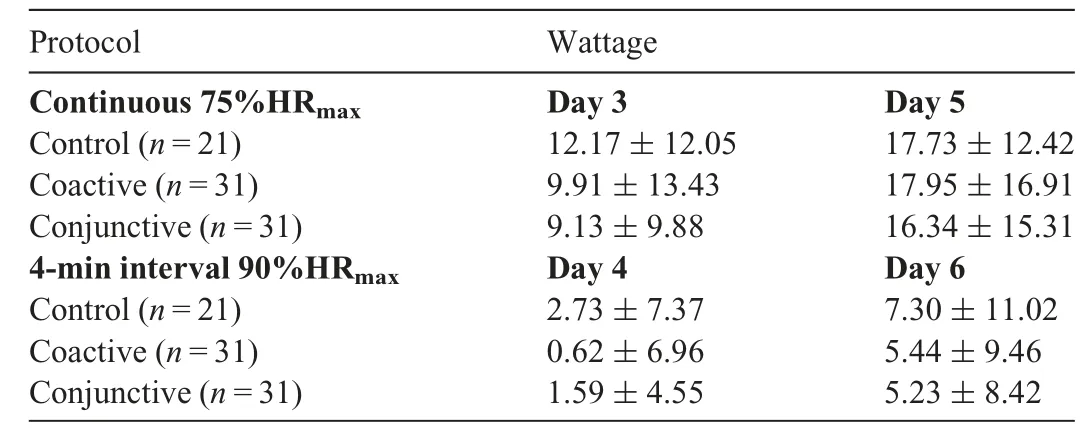

For the primary dependent effort variable of watts difference(from programmed watts),two 3(Condition:IC,COAP,CONJ)×2(Day)ANOVAs with repeated measures on the last factor wereconducted.Theserepeated measures ANOVAs examined condition differences for the continuous sessions(Days 3 and 5)and the 4-min sessions(Days 4 and 6),as well as whether there was an interaction between Condition and Day for each type of workout.Continuous-session results showed no signif icant main effect for Condition:F(2,80)=0.19,p=0.83.There was a signif icant effect for Day(i.e.,intensity increased from Day 3 to Day 5):F(1,80)=45.48,p<0.001(see Table 3 for means).However, the Condition-by-Day interaction was not signif icant:F(2,80)=0.45,p=0.64.

Table2Partner relationship variables:perception ratings.

Table3Wattsabovetarget(mean±SD).

Likewise,the results for the 4-min sessions did not demonstrate a signif icant main effect for Condition:F(2,81)=0.50,p=0.61 or Condition-by-Day interaction:F(2,81)=0.25,p=0.78.Again,the effect for Day was signif icant:F(1,81)=31.74,p<0.001.The largest condition differences were observed on experimental Day 6(4-min intervals),with relatively small effect sizes between conditions:CONJ and COAP(d=0.02),ICand COAP(d=0.18),and CONJand IC(d=0.21);these effects were even smaller at Day 5.Descriptive data for baseline days(Day 3,Day 5)and experimental days(Day 4,Day 6)are listed in Table3.

Results for the difference between beginning workload watts and the mean workload for each type of session suggest that participants in all conditions maintained or slightly increased the intensity of each workout.Thisincrease in workout intensity was more evident on Days 5 and 6,and the mean differences were higher than baseline Days 3 and 4.Again,there were no signif icant differences between conditions because all 3 groups demonstrated this general increase of intensity effect in a similar pattern.

Effort was highly variable for the dependent variable of watt difference and non-normally distributed for each day.Parametric analyses were performed because ANOVA is generally robust against violation of normality.41,42However,non-parametric analyses were also performed to verify the results.There were no signif icant differences with a Pearson χ2comparison andφeffect size analysis of a Mood's Median Test orχ2analysiswith a Kruskal-Wallistest.

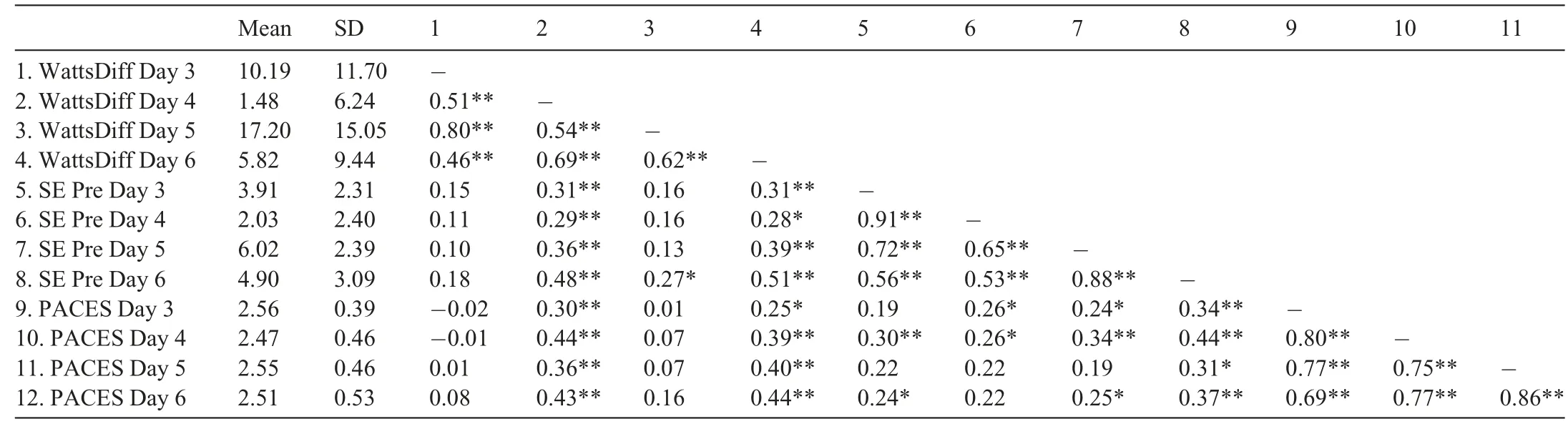

Overall means,standard deviations,and correlations for performance(watts difference),pre-exercise self-eff icacy,and enjoyment arereported in Table4.Effort during sessions Days 3 and 5 was not signif icantly correlated with pre-exercise self-eff icacy or enjoyment.In contrast,these variableswere all signif icantly correlated on the more intense 90%HRmaxDays 4 and 6.

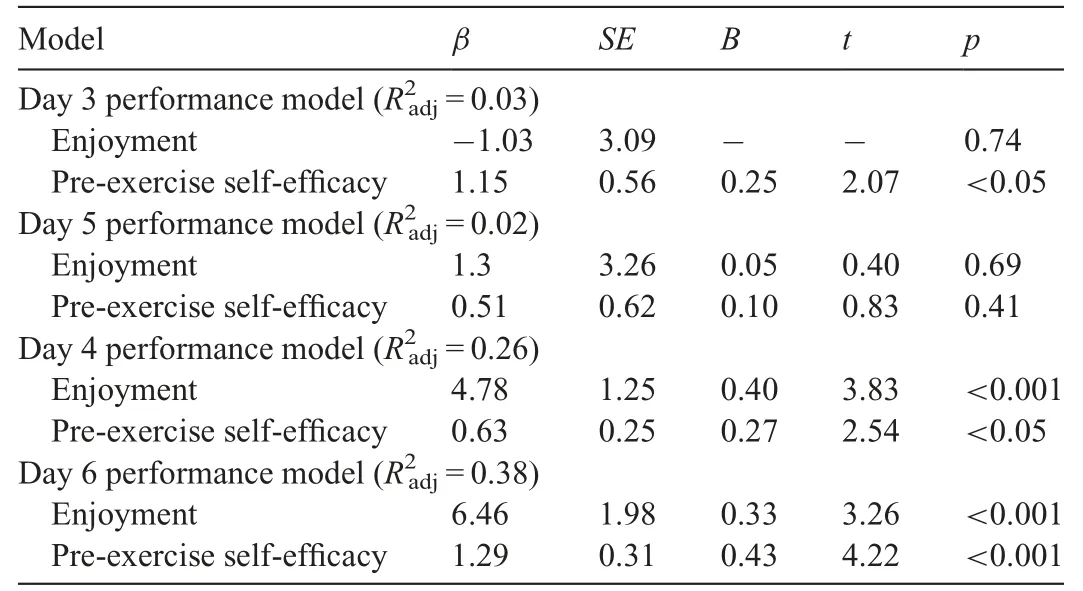

In light of the correlation patternsfor these variables across all conditions,multiple regression analysis was used to test if the pre-exercise self-eff icacy and session enjoyment ratings signif icantly related to the participants'performance effort(Table 5).Asthe correlations suggest,the resultsof the regression indicated that the two-factor model explained 26%of the variance on Day 4:R2adj=0.26,F(2,70)=13.40,p<0.001,and 38%of the variance on Day 6:R2adj=0.38,F(2,70)=22.41,p<0.001.On Day 4,pre-exercise self-eff icacy signif icantly related to performance:(β=0.27,p<0.05),as did enjoyment(β=0.40,p < 0.001).A similar signif icant relationship was noted on Day 6 for self-eff icacy(β=0.43,p<0.001)and enjoyment(β=0.33,p<0.001).On Days 3 and 5,the 2 factors did not contribute to the performance variance:R2adj=0.03,F(2,70)=2.14,p=0.13;R2adj=0.02,F(2,70)=0.50,p=0.61.

4.Discussion

We sought to examine motivation to maintain or increase intensity during an aerobic exercise protocol embedded in a simple exergame using a K¨ohler group dynamics paradigm with physically active middle-aged adults.The results did not reveal signif icant differences between participants in a CONJ condition(an interdependent task group)and those in a COAP condition(thecoactiveindependent task group),or when compared to non-partnered ICs.All participants,however,were motivated to increase performance over their baseline target.Furthermore,even while cycling at levels of intensity above 75%and 90%of HRmax,participants enjoyed the exercise task and did so whileworking out with and without asoftwaregenerated character.Both enjoyment and pre-exercise self-eff icacy partially explained performance gains on the most intense interval days,Days 4 and 6.Yet,similar positive trendsin self-eff icacy,aswell aspositive ratingsof enjoyment,did not predict performance increaseson the 75%HRmaxdays,Days3 and 5.

Table4Means,SDand correlations:effort(WattsDiff),pre-self-eff icacy(SEPre),and enjoyment(PACES).

Table5Performanceregression modelsfor self-eff icacy and enjoyment(PACES).

It is quite unusual to fail to obtain a K¨ohler motivation gain effect.In 2 previous studies in which the K¨ohler effect was not demonstrated,lack of immediate feedback on the participants'own performance,as well as feedback on their partner's performance,was identif ied as the cause.43,44The lack of informative performance feedback may affect both K¨ohler mechanisms(i.e.,social comparison and team indispensability)if participants are not able to compare their ability with that of their partnersand set goalsto upwardly matchor competewith theperformanceof their teammates.43,44Without suff icient continuous and immediate feedback,participantsmay also not perceivehow and if their performanceisinstrumental to the team outcome,potentially inhibiting the K¨ohler motivation gain.

In thepresent study,feedback(asperformancedata)wasavailable during the session,but insuff icient realism may have served to undermine its role in reinforcing the CONJ manipulation.In theory,participants had the capability to increase the intensity of the workout(i.e.,increase watts)to increase the distance cycled and possibly match or surpass the superior SGP.Although increasing intensity would result in longer distance and watt numerical values displayed on the video screen(representing a more intense workout),it did not change how far the SGP appeared to becycling out in front of theparticipant.Asthesuperior partner,the SGP appeared to maintain a constant moderate lead throughout thesession.Thisvisual invariability of theparticipant-SGP performance gap,regardless of the participant's own behavior,would both tend to make this feedback incredible and uninformative.If increasing intensity felt different but did not correspond to changes in the partner distance discrepancy,participants may have chosen to ignore it and hence behaved much as those without a partner(which was,essentially,thepattern of the data).Futurevariationsof this K¨ohler paradigmcould testwhether this visual invariability moderates the motivation effect using a high-f idelity simulation in which the distance between the participant and the SGP is,or not,sensitive to the participant's momentary level of effort.

It is possible that enjoyment and self-eff icacy played a role in motivating performance during the f inal high-intensity session days,Days 5 and 6.Not surprisingly,participants in all conditions increased in self-eff icacy beliefs after successfully completing each workout session compared to presession ratings.Likewise,presession self-eff icacy was higher when participants returned for the next similar session(i.e.,continuous 75%HRmaxor 4-min interval 90%HRmax)than were ratings collected immediately after successfully completing the previous session.Upward trends in self-eff icacy,as well as consistent positive enjoyment ratings,were signif icantly related to performance in our regression models on the higher-intensity 4-min interval days,although not on the continuous-session days.In support of self-eff icacy theory,participants may have felt a great sense of accomplishment when f irst enduring such a challenging task as these 4-min intervals.These feelings of accomplishment may then have led to an increased sense of self-eff icacy and enjoyment about that accomplishment,and that provided the motivation to work even harder at the next 4-min interval day.Furthermore,the f indings for self-eff icacy and enjoyment may partially be explained by the f itnessof the sample and the relative challenges of the 2 different session types.For example,for these active adults,the 30-min continuous session may have been perceived as boring and not challenging,which was exacerbated by a relative comparison to successfully mastering the more vigorous interval sessions.It is possible that 30 min of high-intensity vigorous aerobic cycling(even at 75%HRmax)was not compelling enough to concern the majority of participants.Another possibility isthat there was simply more time for participants to concentrate on potential f laws in SGP feedback and devise alternative goals to those established by the CONJ team manipulation.The more intense sessions provided an opportunity for participants to master the challengesand,as a result,be inf luenced by their enjoyment and eff icacy perceptions.

In terms of SGP relationship variables,participant responses to the video display and SGPs successfully reinforced these adults'willingness to accept and interact with a virtual character.Attitudes toward the SGPs were positive,while participants also viewed them asattractive and not eerie,yet recognizing that the SGPs were not humanlike.Participantsin both partnered conditions identif ied as exercising in a group,but neither clearly believed they were working out as a team—in other words,not with someone to be dependent on.A longer exercise training period may be necessary to build that senseof being in ateam structure.

As previously noted,insuff icient feedback(invariability of partner distance to participant)may have contributed to the lack of f indings.This study did not intend to directly test this aspect of relative performance feedback,but future research could explore the moderating effect of this variable.However,performance variability may have posed the biggest limitation to answering our research question because high variance in participant performance posed challenges to both interpreting data and identifying experimental differences.The variability is not surprising in light of examining responses to highintensity exercise in a relatively small community of adults(even a physically active one),with an inherent wide range of age,ability,motivation,and personal characteristics.

This experiment does extend the K¨ohler motivation gain effect literature in that it continued to explore the boundaries and moderators of this group dynamic.Despite the lack of K¨ohler motivation gains in the CONJ condition,this experiment demonstrated increases in performance over baseline in an intense exercise protocol.Even while cycling at intensity levelsabove 75%and 90%of HRmax,maleand femaleparticipants enjoyed the exercise task and did so while working out with and without asoftware-generated character.

5.Conclusion

Thisexperiment did not replicatethe K¨ohler effect in eliciting motivation gainswhen measured asincreasesin intensity of aerobic exercise protocol with an SGP.High exercise condition realism and feedback(e.g.,continuous SGP distance variability in sync with participant changes in effort)has been identif ied as a potentially crucial factor for evoking the motivation-enhancing mechanisms of the K¨ohler effect.Furthermore,f indings suggest thatperceptionsof participants'enjoymentand self-eff icacy could predict the degree of motivation gains during the more intense 4-min interval days,although not during the less intense 30-min continuous days.In fact,all participants were motivated to increaseperformanceover their baselinetarget.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by research grant#MA03401(Feltz,PI),NASA/National Space Biomedical Research.The authors would like to thank Samuel Forlenza,Emery Max,Seungmin Lee,Tayo Moss,William Jeffery,Greg Kozma,and all theundergraduateresearch volunteers.

Authors'contributions

SS was a project manager,carried out the study,performed statistical analysis,and drafted the manuscript;CRH was a project manager,carried out the study,and helped draft the manuscript;NLK was a co-investigator,participated in study design and conception,and contributed to statistical analysis and manuscript revision;BW was a co-investigator,created the study software,and helped with manuscript revision;AE was a project manager,carried out the study,and helped revise the manuscript;JMPwas a co-investigator and participated in study design and manuscript revision;LPSwas a co-investigator,participated in study design and conception,assisted with exercise protocol design,and helped with manuscript revision;DLF was the principal investigator,participated in study design and conception,oversaw statistical analysis,and assisted with manuscript revision.All authors have read and approved the f inal version of the manuscript,and agreewith the order of presentation of the authors

Competinginterests

Theauthorsdeclarethat they haveno competing interests.

References

1.Carlson SA,Fulton JE,Schoenborn CA,Loustalot F.Trend and prevalenceestimatesbased on the2008 Physical Activity Guidelinesfor Americans.Am JPrev Med 2010;39:305-13.

Now, the dove was nearly driven distracted at the jackal s words; but, in order to save the lives of the other two, she did at last throw the little one out of the nest

2.Tucker JM,Welk GJ,Beyler NK.Physical activity in U.S.:adultscompliancewith the Physical Activity Guidelinesfor Americans.Am JPrev Med 2011;40:454-61.

3.U.S.Department of Health and Human Services.2008 physical activity guidelines for Americans:be active,healthy,and happy.Washington,D.C.Government Printing Off ice;2008.Available at:http://www.health.gov/paguidelines/guidelines/default.aspx ;[accessed 19.10.2013].

4.Gellert P,Ziegelmann JP,Warner LM,Schwarzer R.Physical activity intervention in older adults:does a participating partner make a difference?Eur JAgeing 2011;8:211.doi:10.1007/s10433-011-0193-5.

5.Kassavou A,Turner A,French DP.Do interventions to promote walking in groups increase physical activity?A meta-analysis.Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2013;10:18.doi:10.1186/1479-5868-10-18.

6.Zajonc RB.Social facilitation.Science1965;149:269-74.

7.Karau SJ,Williams KD.The effects of group cohesiveness on social loaf ing and social compensation.Group Dynam Theo Res Pract 1997;1:156-68.

8.Latan′e B,Williams K,Harkins S.Many hands make light the work:the causes and consequences of social loaf ing.J Person Soc Psychol 1979;37:822-32.

9.Hertel G,Kerr NL,Mess′e LA.Motivation gains in performance groups:paradigmatic and theoretical developments on the K¨ohler effect.J Pers Soc Psychol 2000;79:580-601.

10.Kerr NL,Hertel G.The K¨ohler group motivation gain:how to motivate the“weak links”in agroup.Soc Person Psychol Comp 2011;5:43-55.

11.K¨ohler O.Physical performancein individual and group situations.(Kraftleistungen bei Einzel-und Gruppenabeit).Industrielle Psychotechnik 1926;3:274-82.[in German].

12.Steiner ID.Group process and productivity.New York,NY:Academic Press Inc.;1972.

13.Kerr NL,Mess′e LA,Seok DH,Sambolec EJ,Lount Jr RB,Park ES.Psychological mechanisms underlying the K¨ohler motivation gain.Pers Soc Psychol Bull 2007;33:828-41.

14.Festinger L.A theory of social comparison processes.Human Relations 1954;7:117-40.

15.Mess′e LA,Hertel G,Kerr NL,Lount Jr RB,Park ES.Knowledge of partner'sability as a moderator of group motivation gains:an exploration of the K¨ohler discrepancy effect.JPers Soc Psychol 2002;82:935-46.

16.Tour′e-Tillery M,Fishbach A.How to measure motivation:a guide for the experimental social psychologist.Soc Person Psychol Comp 2014;8:328-41.

17.Weber B,Hertel G.Motivation gains of inferior group members:a meta-analytical review.JPers Soc Psychol 2007;93:973-93.

18.Feltz DL,Kerr NL,Irwin BC.Buddy up:the K¨ohler effect applied to health games.JSport Exerc Psychol 2011;33:506-26.

19.Irwin BC,Scorniaenchi J,Kerr NL,Eisenmann JC,Feltz DL.Aerobic exercise is promoted when individual performance affects the group:a test of the K¨ohler motivation gain effect.Ann Behav Med 2012;44:151-9.

20.Samendinger S,Max EJ,Feltz DL,Kerr NL.Back to the future:the K¨ohler motivation gain in exergames.In:Karau SJ,editor.Individual motivation within groups.Social loaf ing and motivation gains in work,academic,and sportsteams.Cambridge,MA:Academic Press;2018.

21.Kravitz L.High-intensity interval training;2014.Available at:http://www.acsm.org/public-information/brochures;[accessed 25.08.2016].

22.Hwang CL,Wu YT,Chou CH.Effect of aerobic interval training on exercise capacity and metabolic risk factors in people with cardiometabolic disorders:ameta-analysis.JCardiopulm Rehabil Prev 2011;31:378-85.

23.Weston KS,Wisløff U,Coombes JS.High-intensity interval training in patients with lifestyle-induced cardiometabolic disease:a systematic review and meta-analysis.Br JSports Med 2014;48:1227-34.

24.Bartlett JD,Close GL,MacLaren DP,Gregson W,Drust B,Morton JP.High-intensity interval running is perceived to be more enjoyable than moderate-intensity continuous exercise:implications for exercise adherence.JSports Sci2011;29:547-53.

25.Perri MG,Anton SD,Durning PE,Ketterson TU,Sydeman SJ,Berlant NE,et al.Adherenceto exerciseprescriptions:effectsof prescribing moderate versus higher levels of intensity and frequency.Health Psychol 2002;21:452-8.

26.Saanijoki T,Nummenmaa L,Eskelinen JJ,Savolainen AM,Vahlberg T,Kalliokoski KK,et al.Affective responses to repeated sessions of high-intensity interval training.Med Sci Sports Exerc 2015;47:2604-11.

27.Reeves B,Nass C.The media equation:how peopletreat computers,television,and new media like real people and places.New York,NY:Cambridge University Press;1996.

28.Nass C,Steuer J,Tauber ER.Computers are social actors.In:Adelson B,Dumais S,Olson J,editors.Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems.Association for Computing Machinery(ACM);Boston,MA,April 24-28;1994.p.72-8.

29.Nass C,Moon Y,Carney P.Arepeoplepoliteto computers?Responsesto computer-based interviewing systems1.J Appl Soc Psychol 1999;29:1093-109.

30.Nass C,Fogg BJ,Moon Y.Can computers be teammates?Int J Hum-Compr Stu 1996;45:669-78.

31.Feltz DL,Forlenza ST,Winn B,Kerr NL.Cyber buddy is better than no buddy:atest of the K¨ohler motivation effect in exergames.Games Health J 2014;3:98-105.

32.Max EJ,Samendinger S,Winn B,Kerr NL,Pfeiffer KA,Feltz DL.Enhancing aerobic exercise with a novel virtual exercise buddy based on the K¨ohler effect.Games Health J 2016;5:252-7.

33.Samendinger S,Forlenza ST,Winn B,Max EJ,Kerr NL,Pfeiffer KA,et al.Introductory dialogue and the K¨ohler effect in software-generated workout partners.Psychol Sport Exerc 2017;32:131-7.

34.McAuley E,Blissmer B.Self-eff icacy determinants and consequences of physical activity.Exerc Sport Sci Rev 2000;28:85-8.

35.Moritz SE,Feltz DL,Fahrbach KR,Mack DE.The relation of selfeff icacy measures to sport performance:a meta-analytic review.Res Q Exerc Sport 2000;71:280-94.

36.Bandura A.Self-eff icacy:the exercise of control.New York,NY:W.H.Freeman and Company;1997.

37.Ploutz-Snyder LL,Downs M,Ryder J,Hackney K,Scott J,Buxton R,et al.Integrated resistance and aerobic exercise protectsf itness during bed rest.Med Sci Sports Exerc 2014;46:358-68.

38.Raedeke TD,Amorose AJ.A psychometric evaluation of a short exercise enjoyment measure.J Sport Exerc Psychol 2013;35(Suppl.1):S110.doi:10.1123/jsep.35.s1.s75.

39.Ho C-C,MacDorman KF.Revisiting the uncanny valley theory:developing and validating an alternative to the Godspeed indices.Comp Human Behav 2010;26:1508-18.

40.Faul F,Erdfelder E,Lang AG,Buchner A.G*Power 3:af lexible statistical power analysisprogram for the social,behavioral,and biomedical sciences.Behav Res Methods2007;39:175-91.

41.Rasch D,Guiard V.The robustness of parametric statistical methods.Psychol Sci2004;46:175-208.

42.Schmider E,Ziegler M,Danay E,Beyer L,B¨uhner M.Is it really robust?Reinvestigating the robustness of ANOVA against violations of the normal distribution assumption.Methodology 2010;6:147-51.

43.Hertel G,Niemeyer G,Clauss A.Social indispensability or social comparison:the why and when of motivation gains of inferior group members1.JAppl Soc Psych 2008;38:1329-63.

44.Kerr NL,Mess′e LA,Park ES,Sambolec EJ.Identif iability,performance feedback and the K¨ohler effect.GPIR:Group Proc Intergroup Rela 2005;8:375-90.

Journal of Sport and Health Science2019年3期

Journal of Sport and Health Science2019年3期

- Journal of Sport and Health Science的其它文章

- Corrigendum Corrigendum to“Denervated muscleextract promotesrecovery of muscle atrophy through activation of satellite cells.An experimental study”[JSport Health Sci8(2019)23-31]

- Original article Adolescents'personal beliefsabout suff icient physical activity aremore closely related to sleep and psychological functioning than self-reported physical activity:A prospectivestudy

- Original article Parents'participation in physical activity predicts maintenance of some,but not all,types of physical activity in offspring during early adolescence:A prospective longitudinal study

- Original article Determination of functional f itness age in women aged 50 and older

- Original article Association of objectively measured physical activity and sedentary time with health-related quality of lifein women with f ibromyalgia:Theal-′Andalusproject

- Original article Classif ication of higher-and lower-mileage runners based on running kinematics