Original article Classif ication of higher-and lower-mileage runners based on running kinematics

Christin A.Clermont ,Angkoon Phinyomrk ,b,Sen T.Osis ,c,Reed Ferber ,c,d,*

a Faculty of Kinesiology,University of Calgary,Calgary,ABT2N 1N4,Canada b Institute for Scientif ic Interchange(ISI)Foundation,Turin 10126,Italy

c Running Injury Clinic,Calgary,ABT2N 1N4,Canada

d Faculty of Nursing,University of Calgary,Calgary,ABT2N 1N4,Canada

Abstract Background:Running-related overuse injuries can result from the combination of extrinsic(e.g.,running mileage)and intrinsic risk factors(e.g.,biomechanics and gender),but the relationship between these factors is not fully understood.Therefore,the f irst purpose of this study was to determine whether we could classify higher-and lower-mileage runners according to differences in lower extremity kinematics during thestance and swing phases of running gait.The second purpose was to subgroup the runners by gender and determine whether we could classify higherand lower-mileage runners in male and female subgroups.Methods:Participantswereallocated tothe“higher-mileage”group(≥32 km/week;n=41(30 females))or to the“lower-mileage”group(≤25 km;n=40(29 females)).Three-dimensional kinematic datawerecollected during 60 sof treadmill running at aself-selected speed(2.61±0.23 m/s).A support vector machine classif ier identif ied kinematic differences between higher-and lower-mileage groups based on principal component scores.Results:Higher-and lower-mileagerunners(both genders)could beseparated with 92.59%classif ication accuracy.When subgrouping by gender,higher-and lower-mileage female runners could be separated with 89.83%classif ication accuracy,and higher-and lower-mileage male runners could be separated with 100%classif ication accuracy.Conclusion:These results demonstrate there are distinct kinematic differences between subgroups related to both mileage and gender,and that these factors need to be considered in future research.2095-2546/©2019 Published by Elsevier B.V.on behalf of Shanghai University of Sport.This is an open access article under the CCBY-NC-ND license(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

Keywords:Biomechanics;Clinical biomechanics;Gait analysis;Kinematics;Motion analysis;Running mileage;Running subgroups

1.Introduction

Running isoneof themost common sportsand recreational activities around the world.However,many runners will experiencearunning-related injury each year,withstudiesreporting incidence rates ranging between 18.2%and 92.4%.1-3The etiology of overuse running injuries is multifactorial and can result from theinteraction of many extrinsic(e.g.,weekly training days,footwear,and weekly training mileage)and intrinsic risk factors(e.g.,age,anatomic factors,foot strike pattern,biomechanics,and gender).4Some research suggests weekly running mileageto bea leading extrinsic risk factor associated with running-related injuries,2,5whileother studieshaveshown no signif icant differencesin injury proportionsbetween higherand lower-mileage runners.6,7

Recreational runners with a long history of running have been shown to demonstrate less frequent knee pain,as compared to non-runners,which may be the result of differences in running gait patterns,among other intrinsic and extrinsic factors.8On the other hand,a study by Silvernail et al.9demonstrated that older adultsexhibited similar movement patterns and coordination variability to younger runners when the groups were matched for weekly running mileage.These similarities may indicate that maintaining a running program with higher weekly mileage may be protective against an increased risk of certain types of injuries associated with the neuromuscular degenerative effects of aging.Other studies have also shown runners who engage in high weekly running mileage tend to sustain more hip and hamstring injuries,10whereasrunnerswith low weekly running mileagesustain more injuriesaround theknee,such aspatellofemoral pain.6To better understand theunderlying interaction between running mileage and specif ic typesof injuries,abiomechanical analysisof highand low-mileage runners may be useful.However,there has beenlimited researchintotheinteractionbetweenrunningkinematics and weekly training mileage.

To our knowledge,only one study has explored the differences in running gait kinematics between higher-and lowermileage runners to gain insight into potential atypical or injurious pathomechanics.Boyer et al.11reported differences between higher-and lower-mileage runners with respect to transverseplanepelvic and hip;frontal planehip and knee;and sagittal and frontal planefoot kinematics.However,only stance phase kinematics were analyzed,and Watari et al.12reported that lower limb kinematics during swing phase are also important to consider when discriminating between running subgroups related to injury.Additionally,Schmitz et al.13reported certain kinematic variables during swing(e.g.,foot and thigh positions)to be signif icant predictors for impact peak and loading rate during running,which are considered important metrics related to overuse running-related injuries and associated with running injuries such as tibial stress fractures.14Therefore,it is important to consider gait kinematics throughout both the stance and swing phases.

Boyer et al.11also grouped males and females together in each mileage group.It is well documented that distinct kinematic differences exist between male and female runners,which are primarily related to frontal and transverse motion of the knee and hip.15,16Therefore,it is important to further subgroup runnerswith differentweekly running mileagein order to improve homogeneity of these running subgroups and accurately quantify their running kinematics.In support of this statement,Gehring et al.17reported gender-related differences in frontal plane hip and knee kinematics in high mileage runners,but runnerswith low mileagewerenot included in this investigation.However,theseauthors17did not exploreany sagittal or transverse plane kinematic differences.Thus,a more thorough analysisof three-dimensional(3D)kinematic gait differencesrelated in male and female subgroups between higherand lower-mileage runners is needed to provide greater insight into the relationship between weekly mileage,gender,and running biomechanics.

Despite the potential for many features needed to classify male and female,higher-and lower-mileage runners,too many discrete kinematic variables in the analysis can complicate the clinical interpretation of the gait patterns for these homogeneous running subgroups.Furthermore,analyzing the discrete kinematic variables with traditional inferential statistics ignores important information about the entire lower limb's coordination of segment motions during running.To overcome these shortcomings,recent studies have used a principal component analysis(PCA)in order to analyze all kinematic variables and time points and allow for a better understanding of the segment couplings and joint motion in all 3 planes of motion.12,16,18-21A PCA approach,combined with machine learning methods(e.g.,support vector machine(SVM)),have also been applied successfully in running biomechanics research to separate and classify running subgroups according to age,gender,performance,and runningrelated injuries with greater than 80%accuracy.16,18-20,22Thus,a similar approach may be used to separate and classify runners according to gender and mileage.

The f irst purposeof thisstudy wasto determinewhether we could classify higher-and lower-mileage runners according to differencesin lower extremity kinematicsduring thestanceand swing phases of running gait.The second purpose was to subgroup the runners by gender and determine whether we could classify higher-and lower-mileage runners in male and female subgroups.We hypothesized that we could classify higher-and lower-mileage runners in all groups(i.e.,(1)both genders,(2)females,and(3)males)with greater than 80%accuracy.We further hypothesized,based on the aforementioned research,that differences between mileage groups would be primarily related to frontal and transverse plane kinematics.

2.Methods

2.1.Subjects

Kinematic data during treadmill running were queried from an existing database21and 81 healthy runners were included in this study.To build upon previous research,we chose to use separate lower-and higher-mileage runners by using the same dichotomy as Boyer et al.11As a result,40 runners(29 females and 11 males)who ran a weekly self-reported average of≤25 km(20.06±4.22 km/week,mean±SD)were labelled as“lower-mileage”runners,and 41 runners(30 femalesand 11 males)who ran a weekly self-reported average of≥32 km(49.65±16.31 km/week)were labelled as“higher-mileage”runners.A recall bias may be associated with self-reported weekly running mileage,but Diderisken et al.23compared selfreported subjective evaluation of running mileage with Global Position System-measured distance,and found no signif icant difference between the 2 methods.Based on this evidence,we are conf ident that the self-reported weekly mileage from runners in our study accurately ref lects whether they meet the higher-or lower-mileage running groups.Data collection was approved by the University of Calgary's Conjoint Health Research Ethics Board(CHREB:REB15-0557),and all participants provided written informed consent prior to participating.

2.2.Data collection

An 8-camera VICON motion capturesystem(MX3+;Vicon Motion Systems,Oxford,UK)wasused to collect3Dkinematic data at 200 Hz during running on an instrumented-treadmill(Bertec Corp.,Columbus,OH,USA).Twenty-two spherical retro-ref lective markers(9-mm diameter;Mocap Solutions,Huntington Beach,CA,USA)were placed over the following anatomic landmarks bilaterally(Fig.1):1st and 5th metatarsal heads;medial and lateral malleoli;tibial tuberosity;head of the f ibula;medial and lateral femoral condyles;greater trochanter;anterior superior iliac spine;and iliac crest.Technical marker clusters,comprised of rigid,plastic shells,were positioned on thepelvis(3 markers)and bilateral thigh and shank(4 markers each)withself-adheringstraps.Threemarkersweretaped tothe heel contour of each of the test shoes.These 25 technical markers represented 7 rigid segments.

Following placement of all the anatomic and technical markers,the participant was asked to stand on the treadmill for a static trial.Standing position was controlled using a graphic template placed on the treadmill with their feet positioned 0.3 m apart and pointing straight ahead.Once the participant was in the standardized position,he or she was asked to cross his or her arms over the chest and stand still while 1 s of marker location data were recorded.Upon completion of the static trial,the anatomic markers were removed to allow the participant to move with less restriction.Following approximately 5 min of acclimation,running kinematic data were collected for 60 swhileeach participant ran on thetreadmill at a self-selected speed(2.61±0.23 m/s,mean±SD)while wearing standardized footwear(Air Pegasus,Nike,Beaverton,OR,USA).

2.3.Data analysis

2.3.1.Initial input data

Joint angles were calculated using 3D GAIT custom software(Running Injury Clinic Inc.,Calgary,Canada)according to previously published methods24,25and normalized to 35 data points for stance and 65 data points for swing.To detect the timing of foot strike and toe-off events,methodology using a PCA combined with a machine learning approach was employed,and these methods have been previously detailed in Osiset al.26Kinematic datawereaveraged from 10 consecutive stridesof datato producemean anglesfor all 3planesof motion for each of the3 lower extremity joints(ankle,knee,and hip)in thelocal coordinatesystem aswell asthepelvissegment in the global coordinate system.Kinematic angles were also calculated for the foot segment in the global coordinate system,but only for the transverse and sagittal planes.The gait data points(14 waveforms×100 time points)were combined into one 1400-dimensional row vector for each participant.

2.3.2.Feature extraction

Given the large number of data points and potential redundancy of data,a PCA was used to reduce the data.PCA is a linear transformationtechniqueused toconvertasetof possibly correlated variablesinto a set of linearly uncorrelated variables by determining new bases(principal components(PCs))that maximize variance sequentially in each PC.27Prior to the PCA,all variables were standardized to a mean of 0 and standard deviation of 1 by calculating thez-scorefor each variable.Asa result,theinput vector for the PCA wasan 81-by-1400 matrix,which generated an 81-by-80 PC scores matrix(i.e.,a total of 80 PCs).

2.3.3.Machine learning

To examine the utility of PCA features in identifying and discriminating the differences between higher-and lowermileage runners in the 3 groups of interest(i.e.,(1)both genders,(2)female runners,and(3)male runners)an SVM approach was used and evaluated based on classif ication accuracy.Themodels were created using the PCscoresasinput for thelinear SVM16,28with asoft margin parameter c set at 1 based on the methods reported by Fukuchi et al.19and Phinyomark et al.16to perform the classif ications for each group comparison.To compare higher-vs.lower-mileage groups,irrespective of gender,an 81-by-80 matrix was used as baseline feature vector for the SVM classif ier.To separate and classify higherand lower-mileage runners in the female subgroup,a 59-by-80 initial input vector was used as initial input for the SVM classif ier.To separate and classify higher-and lower-mileage runners in the male subgroup,a 22-by-80 initial input vector was used as initial input for the SVM classif ier.

For thefeatureselection procedure,thenumber of PCscores used as features in the SVM classif iers were increased in descending order of Cohen's d effect size,and once the maximumclassif icationrateof the SVM wasreached according to the 10-fold cross validation methods,these features were considered the optimal number and used as the output for the SVM.19,28For the 10-fold cross validation,PC data were randomly partitioned into10 equally sized sub-datasets.Then,a singlesub-datasetwasretained astestingdatawhiletheremaining 9 sub-datasetswere used astraining data for the classif ication model.The cross-validation process was then repeated 10 times,and a single classif ication rate was computed by averaging from all 10 results.16

Fig.1.Placement of theref lectivemarkers on the lower extremities.Anatomic markers(gray circles)were used to create segmental anatomic coordinate systems while the technical clusters(open circles)were used for tracking purposesduring therunning trials,and virtual joint centers(black circles)were def ined relative to the technical coordinate system using the technical marker clusters during thestanding calibration trial,and were created at thehip,knee,and ankle.

2.4.Evaluating functions

All analyses were performed using customized MATLAB 9.0 software(The Mathworks Inc.,Natick,MA,USA).Three separate independent t tests(p<0.05)compared anthropometric(i.e.,height and mass),speed,and demographic(i.e.,age,running experience,and weekly running mileage)measures between(1)higher-and lower-mileagerunners,(2)higher-and lower-mileage female runners,and(3)higher-and lowermileage male runners.

To visualize differences between groups,all PC scores that were used to yield the maximum accuracy for discriminating between groups were used to reconstruct the original joint and segment angle waveforms.Specif ically,all selected PC scores were multiplied by the transpose of the PC coeff icient matrix.Then,to reconstruct gait waveforms in the original coordinate space,each subject's sample was multiplied by the sample's standard deviation vector with addition of the mean vector.To interpret the biomechanical meaning of the waveforms,the standardized effect size,Cohen's d was used to identify meaningful differences.29Based on Cohen'sconventional criteria,30a meaningful difference between groups was def ined as a large effect size(d≥0.8).

3.Results

3.1.Higher-vs.lower-mileage runners(both genders)

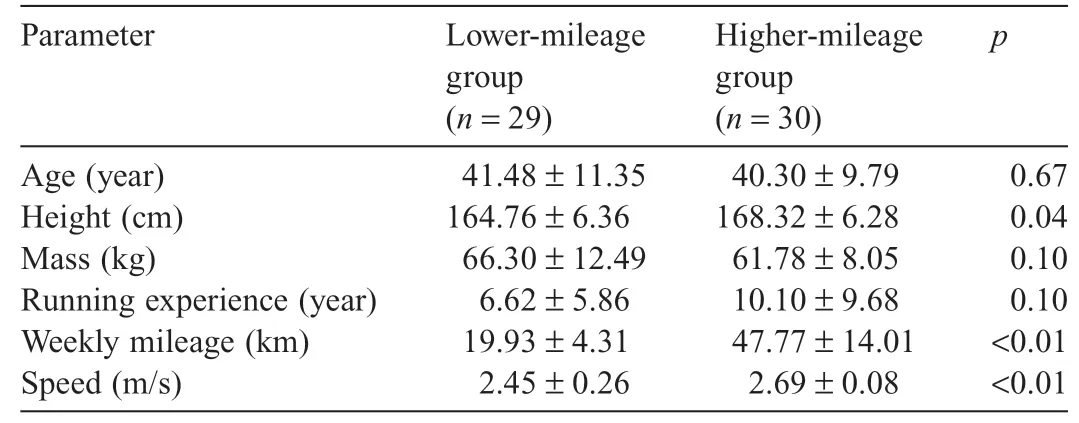

Anthropometric and demographic comparisons between higher-and lower-mileage running groups can be seen in Table 1.Overall,there were no signif icant differences between these groups in terms of age,height,mass,or self-reported yearsof runningexperience.Thehigher-mileagerunnersexhibited a higher self-reported weekly mileage and a signif icantly faster self-selected speed(p<0.01)during the data collection.

Higher-and lower-mileage runners could be separated with 92.59%classif ication accuracy using a linear SVM 10-fold cross-validation method with the top 57 ranked PCsexplaining 52.71%of the total variance.Meaningful differences(d>0.8)in kinematic variables for higher-and lower-mileage runners were found in the transverse plane foot angles during midswing(54%-61%of the gait cycle,Fig.2).

Fig.2.Both genders:themean of individual time-normalized transverseplane foot angles from kinematic analyses for higher-and lower-mileage runners(both genders)during stance phase(1%-35%)and swing phase(36%-100%)of running.Theshaded areaindicatesmeaningful differences(d>0.8)between groups.

3.2.Higher-vs.lower-mileage female runners

For female runners,anthropometric and demographic comparisonsbetween higher-and lower-mileagegroupscan beseen in Table2.Therewereno signif icant differencesbetween these groups in terms of age,mass,or self-reported yearsof running experience.The higher-mileage female runners were signif icantly taller(p=0.04),exhibited a higher self-reported weekly mileage,and a signif icantly faster self-selected running speed(p<0.01)during the data collection.

Higher-and lower-mileage female runners could be separated with 89.83%classif ication accuracy using thetop 47 PCs explaining 45.17%of thetotal variance.Thereweremeaningful differences between higher-and lower-mileage female runners in termsof sagittal planekneemotion atdifferent periodsof the swing phase(49%-57%and 73%-88%of the gait cycle,Fig.3A),sagittal foot motion during late swing(77%-82%of the gait cycle,Fig.3B),as well as transverse knee motion during mid-stance(12%-19%of the gait cycle,Fig.3C).

Table2Female participant characteristics(mean±SD).

Table1Participant characteristics(both genders)(mean±SD).

Fig.3.Female:the mean of individual time-normalized joint and segment angles from kinematic analyses for higher-and lower-mileage female runners during stance phase(1%-35%)and swing phase(36%-100%)of running.(A)sagittal plane knee joint;(B)sagittal plane foot segment;and(C)transverse plane knee joint.The shaded area indicates meaningful differences(d>0.8)between groups.

Table3Male participant characteristics(mean±SD).

3.3.Higher-vs.lower-mileage male runners

For male runners,anthropometric and demographic comparisonsbetween higher-and lower-mileagegroupscan beseen in Table 3.There was only 1 signif icant difference between groups,which wasthehigher-mileagegroup exhibited a higher self-reported weekly running mileage(p<0.01).

Higher-and lower-mileage male runners could be separated with 100%classif ication accuracy by using the top 12 ranked PCs which explain 6.13%of the total variance.There were meaningful differencesbetweenmalehigher-and lower-mileage runners at different points in the gait cycle in all joints and segments for various plane of motion.In brief,lower-mileage male runners demonstrated greater anterior pelvic tilt throughout 92%of the gait cycle compared to their higher-mileage counterparts(Fig.4A).Higher-mileage male runners displayed greater transverse pelvic rotation toward the ipsilateral leg throughout most of the gait cycle(5%-78%and 85%-93%,Fig.4B).Greater hip adduction was observed in the highermileage runners during most of stance and early swing(9%-55%).However,during mid-to late-swing(59%-90%),the opposite effect occurred,in which lower-mileage runners displayed greater hip adduction than higher-mileage male runners(Fig.4C).With respect to knee motion,higher-mileage runners exhibited a more f lexed knee throughout stance(6%-35%)and during the later stages of swing(69%-92%)(Fig.4D).Finally,lower-mileage male runners demonstrated greater foot abduction(i.e.,toe-out)throughout 95%of thegait cycle(Fig.4E).

4.Discussion

4.1.Higher-vs.lower-mileage runners(both genders)

The f irst purpose of this study was to determine whether we could separate and classify higher-and lower-mileage runners,both independently and according to gender,based on differences in running kinematics during stance and swing phases.In support of our hypothesis,higher-and lowermileage runners could be separated with 92.59%classif ication accuracy with the top 57 ranked PCs based on lower extremity gait kinematics and using a multivariate analysis and a machine learning approach.

The f indings of the current study support those of Boyer et al.11and indicate there are systematic differences in running kinematics for higher-and lower-mileage runners.These f indings are also supported by previous research showing that intermediate and higher-order PCs are associated with the subtlemovementpatternsof runninggait31and contain valuable information about between-group variation to help classify different types of runners.Our results provide further evidence thatamachinelearning approach using low-,intermediate-,and higher-order PC scores can provide insight into the complex relationships of biomechanical gait variables for dominant and subtle movements throughout the entire gait cycle for higherand lower-mileage runners.

Fig.4.Male:the mean of individual time-normalized joint and segment angles from kinematic analyses for higher-and lower-mileage male runners during stance phase(1%-35%)and swing phase(36%-100%)of running.(A)sagittal plane pelvissegment;(B)transverse plane pelvissegment;(C)frontal planehip joint;(D)sagittal plane knee joint;and(E)transverse plane foot segment.The shaded area indicates meaningful differences(d>0.8)between groups.

It washypothesized that themeaningful differencesbetween higher-and lower-mileage running groups would be primarily related to transverse and frontal motion.In partial support of this hypothesis,we found meaningful(d>0.8)differences for the foot in the transverse plane,where higher-mileage runners demonstrated greater internal rotation of the foot during midswing.Boyer et al.11reported that higher-mileage runners exhibited greater internal rotation of the foot during stance phase,and the current study signif icantly builds on their research,wherein thefocuswaslimited to stancephaserunning kinematics.Swing phase lower-limb kinematics have been shown to beimportant when classifying runnersand potentially studying the relationship between running mechanics and injury.12,13In particular,Schmitz et al.13indicated that the foot position during mid-swing is predictive of the magnitude of impact peak at foot contact.Impact peak isinherently related to loading rate,which has been associated with lower leg overuse running-related injuries,such as tibial stress fractures.14Although Schmitz et al.13did not explore the relationship between joint or segment angles with impact peak and loading rate,the differences in transverse plane foot angles between higher-and lower-mileage runners in our study may be indicative of different levels of impact peaks and loading rates.This result may help explain why more highly trained,competitive runners experience more lower-leg injuries than recreational runners32but further research is necessary to better understand how these variables are related to injury.

4.2.Higher-vs.lower-mileage female runners

The second purpose of our study was to determine whether we could classify higher-and lower-mileage runners in male and female subgroups separately.In support of our hypothesis,higher-and lower-mileage female runners could be separated with 89.83%,and the differences were primarily related to transverse motion of the knee.Specif ically,during mid-stance,lower-mileage female runners demonstrated greater internal rotation of the knee in the transverse plane of motion as compared to their higher-mileage female counterparts.Increased knee internal rotation can result in greater torsional strain to tissues at the knee joint,such as the iliotibial band.33This postulation is supported by previous research that has shown that females with iliotibial band syndrome exhibit increased knee internal rotation angles during stance in comparison to femalecontrols.18,33Moreover,kneeinjurieshavebeen shownto be more common in lower-mileage runners;6,8,10therefore,the increased knee internal rotation observed in our lower-mileage female runners may provide some biomechanical insight as to the etiology of this injury pattern.

4.3.Higher-vs.lower-mileage male runners

Higher-and lower-mileage male runners could be separated with 100%classif ication accuracy using thetop 12 ranked PCs,which explains 6.13%of the total variance,and there were meaningful differences between higher-and lower-mileage runners in several joints and segments.At the pelvis,lowermileage male runners demonstrated greater anterior tilt throughout 92%of thegait cycleand theseresultscomplement the work of Preece et al.,34who also reported that recreational male runners exhibit a more pronounced thoracic and pelvic inclination than highly trained,elite males.Although Preece et al.34grouped their runners according to race performance,it can be speculated that their elite runners had higher weekly training volume than recreational runners.Similar to Preece et al.,34our f indings challenge some training protocols that instruct recreational runners to increase trunk lean or anterior pelvic tilt to improve performance or reduce injury.35,36Nevertheless,due to the cross-sectional nature of our study,it is diff icult to speculate on the long-term effects of pelvic tilt on performance and injury.

Higher-mileage male runners exhibited greater transverse plane pelvic rotation toward the ipsilateral leg throughout stance and most of swing compared to lower-mileage male runners.Boyer et al.11also found similar results during the stancephase,in which their higher-mileage group also demonstrated greater transverse plane pelvic rotation toward the ipsilateral leg.Furthermore,we found that higher-mileage runners displayed greater hip adduction during stance,which is also consistent with Boyer et al.11Given the potential relationship between increased hip adduction and kneeinjury,37theseresults may be at odds with literature indicating that knee injuries are lessfrequent in higher-mileage runners.However,it is possible that higher-mileagerunnersalso exhibit improved strength and coordination,which mitigates this risk.

Higher-mileage male runners exhibited a more f lexed knee throughoutstance,and during thelater stagesof swinginpreparation for heel strike as compared to lower-mileage male runners.These results are in agreement with previous research that has shown that with training,runners adapt their gait patterns toward a more f lexed knee during the stance phase of running gait and in preparation for toe off.38Greater knee f lexion during stance may increase tibial shock and result in a higher risk for tibial stress injuries.39,40Therefore,this running adaptation may increase the risk of experiencing lower leg injuries,which is a more common injury site for trained,competitive,long-distance runners compared to recreational runners.32

Finally,higher-and lower-mileage male runners exhibited meaningful differences in transverse plane foot motion.Specif ically,lower-mileagemalerunnersdemonstrated greater foot abduction(i.e.,toe-out)throughout 95%of the gait cycle as compared to their higher-mileage counterparts.Increased foot abduction or greater toe-out during thestancephaseof running has been associated with the presence of patellofemoral pain syndrome in runners.41A greater toe out can increase the tibial external rotation,which may then lead to greater knee external rotation and result in patellofemoral pain due to repetitive loading.

4.4.Limitations

Limitationsto thecurrent study areacknowledged.First,the runners self-selected their preferred running speed,and there were signif icant differences in running speed in 2 of the subgroup comparisons.The differences in self-selected speed werelikely dueto differencesin performancelevel and training habits between higher-and lower-mileage runners.Differences in speed have potential confounding effects on running biomechanics;42however,due to the different training habits betweenthese2groups,wechoseaself-selected running speed,rather than a pre-def ined speed,to better represent each runner's“typical”running patternsat their usual performanceand training level.Nevertheless,speed may beaconfounding factor with regard to the kinematics of the female runners.

Secondly,a relatively small sample size was used in this study,especially when using machinelearning methodsto subgroup by gender(30 femalesand 11 males).When employing a machine learning approach and the ratio of the number of subjects to the number of samples is low,there is a risk of overf itting the data,21which may reduce the generalizability of the results.To build more accurate classif ication models,a larger number of samples are needed in future studies.43Nevertheless,we are conf ident in our f indings because similar differences were found with Cohen's effect size(d)and the features used in the SVM underwent a 10-fold cross-validated classif ication procedure.Although a larger sample size would have allowed for amorerobust classif ication model,we believe our f indings would be similar.

5.Conclusion

Using kinematic waveforms,PCA,and an SVM classif ier,the current study was able to separate and classify lower-and higher-mileage runners based on differences in lower-limb kinematic gaitpatternsthroughoutstanceand swing during treadmill running.The current study also demonstrated that there are distinct lower-limb kinematic differences between higher-and lower-mileage runners when further subgrouping by gender.A unique f inding was that sagittal plane kinematics were an important consideration when subgrouping higher-and lowermileage runners,especially in males.Our results suggest that gender needs to be considered to better understand the specif ic kinematic differencesbetween higher-and lower-mileagerunners.These f indings may be used to monitor biomechanical adaptations associated with training that may help runners,coaches,and clinical professionals to assess performance and assess injury risk.For example,if a“lower-mileage”runner's gait pattern begins to resemble that of a“higher mileage”runner,then it may help predict improved running performance or protective mechanisms against running-related knee injuries.With thechangein running biomechanics,however,thisrunner should then be aware of an increased risk of other types of running-related injures(e.g.,tibial stress fractures).On the other hand,if the“higher-mileage”runner's gait kinematics start to resemble that of a“lower-mileage”runner,then this may be predictive of an increased risk of running-related knee injuries.Finally,the f indings of the current study also suggest that runners should employ individualized preventative strategies to reduce the risk of certain types of running-related injuries that are associated with the combination of running biomechanics,gender,and mileage.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this research was partially provided by a Discovery Grant(No.1028495)and Accelerator Award(No.1030390)through the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada(NSERC)along with the Faculty of Kinesiology Dean's Doctoral Studentship Program at the University of Calgary.

Authors'contributions

CAC drafted the manuscript and was involved in the study design and data analysis;AP helped draft the manuscript and was involved in the study design and data analysis;STO performed thedataprocessing,helped with dataanalysisand interpretation,and wasinvolved in critical review of themanuscript;RF was involved in the conception of the study,participated in its design and coordination,participated in data interpretation,and was involved in critical review of the manuscript.All authors have read and approved of the f inal version of the manuscript,and agree with the order of presentation of the authors.

Competinginterests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Journal of Sport and Health Science2019年3期

Journal of Sport and Health Science2019年3期

- Journal of Sport and Health Science的其它文章

- Corrigendum Corrigendum to“Denervated muscleextract promotesrecovery of muscle atrophy through activation of satellite cells.An experimental study”[JSport Health Sci8(2019)23-31]

- Original article Group dynamicsmotivation to increaseexerciseintensity with a virtual partner

- Original article Adolescents'personal beliefsabout suff icient physical activity aremore closely related to sleep and psychological functioning than self-reported physical activity:A prospectivestudy

- Original article Parents'participation in physical activity predicts maintenance of some,but not all,types of physical activity in offspring during early adolescence:A prospective longitudinal study

- Original article Determination of functional f itness age in women aged 50 and older

- Original article Association of objectively measured physical activity and sedentary time with health-related quality of lifein women with f ibromyalgia:Theal-′Andalusproject