Original article Association of objectively measured physical activity and sedentary time with health-related quality of lifein women with f ibromyalgia:Theal-′Andalusproject

Blnc Gvil′n-Crrer*,V′ıctor Segur-Jim′enez b,Fernndo Est′evez-L′opez c,†,Inmculd C′Alvrez-Gllrdo d,Alberto Sorino-Mldondo e,f,Milkn Borges-Cosic Mnuel Herrdor-Colmenero g,Pedro Acost-Mnzno Mnuel Delgdo-Fern′ndez

a ,on behalf of theal-′Andalusproject

a Department of Physical Education and Sport,Facultyof Sport Sciences,University of Granada,Granada 18071,Spain n

b Department of Physical Education,Faculty of Education Sciences,University of C′adiz,C′adiz11519,Spainn

c Department of Psychology,Faculty of Social and Behavioural Sciences,Utrecht University,Utrecht CS3584,the Netherlands n

d Department of Physical Education,Facultyof Education Sciences,Universityof C′adiz,C′adiz11519,Spain

e Department of Education,Faculty of Education Sciences,University of Almer′ıa,Almer′ıa 04120,Spain f SPORTResearch Group(CTS-1024),CERNEPResearch Center,University of Almer′ıa,Almer′ıa 04120,Spain

g Teaching Centre La Inmaculada,University of Granada,Granada 18013,Spain

Abstract Purpose:To examine the association of physical activity(PA)intensity levels and sedentary time with health-related quality of life(HRQoL)in women with f ibromyalgia and whether patientsmeeting the current PA guidelines present better HRQoL.Methods:This cross-sectional study included 407 women with f ibromyalgia aged 51.4±7.6 years.The time spent(min/day)in different PA intensity levels(light,moderate,and moderate-to-vigorous physical activity(MVPA)and sedentary timewere measured with triaxial accelerometry.The proportion of women meeting the American PA recommendations(≥150 min/week of MVPA in bouts≥10 min)was also calculated.HRQoL domains(physical function,physical role,bodily pain,general health,vitality,social functioning,emotional role,and mental health),as well asphysical and mental components,were assessed using the 36-item Short-Form Health Survey.Results:All PA intensity levelswere positively correlated with different HRQoL dimensions(r partial between 0.10 and 0.23,all p<0.05).MVPA was independently associated with social functioning(p<0.05).Sedentary time was independently associated with physical function,physical role,bodily pain,vitality,social functioning,and both the physical and mental component summary score(all p<0.05).Patients meeting the PA recommendations presented better scores for bodily pain(mean=24.2(95%CI:21.3-27.2)vs.mean=20.4(95%CI:18.9-21.9),p=0.023)and better scores for social functioning(mean=48.7(95%CI:43.9-44.8)vs.mean=42.3(95%CI:39.8-44.8),p=0.024).Conclusion:MVPA(positively)and sedentary time(negatively)are independently associated with HRQoL in women with f ibromyalgia.Meeting the current PA recommendations is signif icantly associated with better scores for bodily pain and social functioning.These results highlight the importanceof being physically active and avoiding sedentary behaviors in thispopulation.2095-2546/©2019 Published by Elsevier B.V.on behalf of Shanghai University of Sport.Thisisan open accessarticle under the CCBY-NC-ND license.(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

Keywords:Accelerometry;GT3X+;Mental health;Physical health

1.Introduction

Fibromyalgia is a chronic condition with persistent and widespread pain along with other symptoms such as fatigue,nonrestorative sleep,and cognitive diff iculties.1These factors have a considerable negative impact on the patients'health-related quality of life(HRQoL),2which represents the individuals' perception of physical,mental,and social health status.Because f ibromyalgia has no cure,treatment is usually focused on improving HRQoL along with symptomatology management.

Physical exercise has been shown to be an alternative to pharmacologic treatments in f ibromyalgia,3yet adherence to exercise programs is challenging.4Modifying daily physical activity(PA)might potentially bea more sustainable behavior over time.Previous studies have observed a positive association between PA and HRQoL both in the general population5,6and among those with f ibromyalgia.7,8Nonetheless,fear of pain and worsening of symptoms lead patients to avoid PAs,9and only 20%of them seem to meet the American PA recommendations.10,11The fulf illment of these PA recommendations for the general population has been related to a higher cardiovascular risk in f ibromyalgia,12but it is unclear whether this may also extend to other health outcomes,such as HRQoL.In similar conditions,such as arthritis,those patientsmeeting the PA recommendationsfor arthritis13or thegeneral population14presented a better HRQoL.The intensity and dose of PA to elicit disease-specif ic benef its in f ibromyalgia is yet to be def ined.Previous research studying the inf luence of PA on health of these patients is mainly focused on symptoms15-18or physical domainsof HRQoL outcomes.8,19,20Therefore,the extent to which different PA intensity levels(e.g.,light,moderate,or vigorous)are associated with all domains of HRQoL and which of them is the best indicator of current HRQoL are currently unknown.

Sedentary behaviors,which include activities that involve sitting or reclining and demand only low levels of energy expenditure,21have negative consequences on health independent of those behaviors related to insuff icient PA.22For instance,sedentary time is linked to lower HRQoL in the general population.6,23Patients with f ibromyalgia spend more time of their waking time in sedentary behaviors(on average,48%)than do healthy individuals.11Hence,it is of major clinical and public health interest to assess the extent to which sedentary time is associated with HRQoL in patients with f ibromyalgia because preventing prolonged sedentary behaviorsmight beadvisable.

A detailed characterization of how different PA intensity levels and sedentary time are related to diverse domains of HRQoL would provide valuable information for the design of prospective studies and specif ic PA recommendations for this group of patients.Therefore,the aims of the current study were to test(1)the association of objectively measured PA intensity levels(i.e.,light,moderate,and moderate-to-vigorous physical activity(MVPA)and sedentary time with HRQoL in women with f ibromyalgia,(2)whether different PA intensity levels and sedentary time are independently associated with HRQoL among these patients,and(3)and whether patients meeting the current American PA guidelines present better HRQoL than those not meeting the PA guidelines.We hypothesized that(1)all PA intensity levels(positively)and sedentary time(negatively)are associated with HRQoL in women with f ibromyalgia,(2)PA and sedentary timeareindependently associated with HRQoL among these patients,and(3)patients who meet the current American PA guidelines present better HRQoL than those not meeting the PA guidelines.

2.Materialsand methods

2.1.Participants

A province-proportional recruitment of patients with f ibromyalgia from southern Spain(Andalusia)was planned,as described elsewhere.24Brief ly,patients were contacted through f ibromyalgia associations,email,and social media.After providing detailed information about the aims and study procedures,we obtained written informed consent from all study participants.A total of 646 patients with f ibromyalgia agreed to participate in thestudy.Inclusion criteria for the current study were(1)to have neither acute nor terminal illness nor severe cognitiveimpairment(Mini-Mental State Examination25score<10),(2)to be≤65 yearsold,and(3)to bepreviously diagnosed by a rheumatologist and meet the off icial 1990 American College of Rheumatology(ACR)f ibromyalgia criteria(widespread pain>3 months and pain with≤4 kg/cm2of pressure reported for≥11 of 18 tender points).26The study wasapproved by the Ethics Committee of the Hospital Virgen delas Nieves,Granada(Spain).

2.2.Procedures

On Day 1 of the study,the Mini-Mental State Examination wasadministered and participantsf illed out themodif ied 2010 ACR preliminary criteria,self-reported sociodemographic data,and drug consumption questionnaires.Tender points,anthropometry,and body composition were also assessed.The 36-item Short-Form Health Survey(SF-36)27was given to patients to be completed at home.Two days later,patients returned to thelaboratory,wherequestionnaireswerecollected and checked by the researchers.After that,participants received instructions on how to complete the sleep diary and the accelerometers were provided.The accelerometers and sleep diarieswerereturned to theresearch team 9 dayslater.

2.3.Measurements

2.3.1.Sociodemographic data and drug consumption

We collected sociodemographic data by using a selfreported questionnaire including date of birth,marital status(married/not married),educational level(university/nonuniversity),and occupational status(working/not working).Additionally,to assess an exclusion criterion,participants were asked:“Have you ever been diagnosed with an acute or terminal illness?”Furthermore,patients reported the consumption of antidepressants and analgesics(yes/no)during the previous 2 weeks.

2.3.2.PAlevelsand sedentary time

Patients were asked to wear a triaxial accelerometer GT3X+(Actigraph,Pensacola,FL,USA)for 9 days during the whole day(24 h)except during water-based activities.Thedevicewas worn around the hip,secured with an elastic belt underneath clothing.Datawere collected at a rate of 30 Hz and at an epoch length of 60 s,in concordance with the cut-points validation studies.28,29PA from the 9 consecutive days was recorded,although data from the f irst day(to avoid reactivity)and the last day(device return)were excluded from the analysis.Bouts of 90 continuous minutes(allowance of 2-min interval of nonzero counts with the up-/downstream 30-min consecutive 0 count window for detection of artifactual movements)of 0 count were considered nonwear periods30and were excluded as well.In agreement with prior literature,317 continuous days in total with a minimum of 10 valid hours was required to be included in the analysis.Data download,reduction,cleaning,and analyses were conducted using the manufacturer software ActiLife Version 6.11.7(Actigraph).Accelerometer wear time was calculated by subtracting the sleeping time(obtained from the sleep diary,in which patients indicated the time they went to bed and the time they woke up)from each day.Sedentary time was estimated as the time accumulated below 200 counts/min during periods of wear time.28PA intensity levels(light PA,moderate PA,vigorous PA,and MVPA)were calculated based on recommended PA vector magnitude cut-points:29200-2689,2690-6166,≥6167,and ≥2690 counts/min,respectively.All values were expressed in min/day.We calculated the proportion of women meeting the American PA recommendationsfor adultsaged 18-64 years(≥150 min/week of MVPA for≥10 min at atime).10

2.3.3.HRQoL

HRQoL was evaluated using the SF-36.This questionnaire hasbeen validated for Spanish populations.27The SF-36iscomposed of 36 itemsthat assess8 dimensionsof health(i.e.,physical functioning,physical role,bodily pain,general health,social functioning,emotional role,mental health,and vitality)and 2 component summary scores(i.e.,physical and mental health).The score in each dimension is standardized and ranges from 0(worst health status)to 100(best health status).

2.3.4.Tendernessand diagnostic criteria

Following the 1990 ACR criteria for classif ication of f ibromyalgia,26we assessed 18 tender pointsusing astandard pressure algometer(FPK 20;Wagner Instruments,Greenwich,CT,USA).We obtained the mean pressure of 2 measurements at each tender point.A tender point was considered positive when the patient felt pain at pressure≤4 kg/cm2.The total number of positivetender pointswasrecorded for each patient.Becausedifferent diagnosesfor f ibromyalgiacurrently coexist,wealso complementarily used the modif ied 2010 ACRpreliminary diagnosis criteria32-34(description in the supplementary material)to understand potential discrepancies owing to the patients'classif ications.

2.3.5.Anthropometry and body composition

Weight(kg)and total body fat percentage was assessed using a portable 8-polar tactile-electrode bioelectrical impedance device(InBody R20;Biospace,Seoul,Republic of Korea).The validity and reliability of this instrument have been reported elsewhere.35,36As the manufacturer recommends,we requested participants not to have a shower,not to practice intense PA,and not to ingest large amounts of f luid and/or food in the 2 h before the measurement.Patients were also asked not to wear either clothing(except underwear)or metal objects during the measurement.A stadiometer(Seca 22;Seca Gmbh,Hamburg,Germany)was used to measure height(cm),and body mass index was calculated as weight(kg)divided by height(m)squared.

2.4.Data analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to examine the sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the sample.Participants presented extremely low valuesof vigorous PA(0.4 min/day);therefore,vigorous PA was excluded from all analyses.In preliminary analyses,bivariate correlations were used to explore the role of different variables related to physical,social,and psychological factors that have been shown to determine HRQoL in patientswith f ibromyalgia.37Asaresult,age,marital status,education level,current occupational status,total body fat percentage,and drug consumption(both analgesics and antidepressants)were identif ied as potential confounders and were introduced in all analyses along with total accelerometer wear time.Partial correlation was used to study the individual association of the different PA levels(light PA,moderate PA,and MVPA)and sedentary time with HRQoL(Objective 1)while controlling for all aforementioned covariates.Then,to exploretheindependent association of PA intensity levels and sedentary time with HRQoL(Objective 2),linear regression analyses were conducted.All dimensions of HRQoL(physical functioning,physical role,bodily pain,general health,social functioning,emotional role,mental health,and vitality)and the physical and mental component summary scores(assessing physical and mental health)were entered as dependent variablesin separatemodels.All PA intensity levels(except vigorous PA),sedentary time,and all covariates(sociodemographic variables,drug consumption,and total body fat percentage)were entered simultaneously using a forward stepwiseprocedure based on theexploratory natureof theseanalyses.Moreover,astepwiseprocedure wasused becausetheaim was to observe the best indicator of HRQoL among the PA variables(i.e.,the PA variables that presented the strongest associations).This procedure introduces the variables step by step into the model(if p<0.05)according to the strength of the association with the outcome.The model is reassessed with the addition of every new variable,and variables are left out of the model if p>0.10.Accelerometer wear time was introduced with the“enter”procedure to control all analyses for its effect.Normal probability plots of the standardized residual and scatterplots of residuals were generated to test normality,linearity,and homoscedasticity.The nonautocorrelation assumption was also met(Durbin-Watson test;1.5<d<2.5 for all regression models).No serious multicollinearity problems among the predictor variables of the model were found(all varianceinf lation factor statistics<10.0).

Differences in HRQoL of patients meeting vs.not meeting the current PA guidelines(≥150 min/week of MVPA in bouts of≥10 min;Objective 3)were calculated with multivariate analysis of covariance.The 8 dimensions and the 2 component summary scores of HRQoL were entered as dependent variables,and sociodemographic variables,total body fat percentage,drugs consumption,and accelerometer wear time were entered ascovariates.

Normality was assumed owing to the large sample size and the homoscedasticity assumption of HRQoL(assessed with the Levene test)was reasonably met between patients'meeting vs.not meeting recommendations of PA.All analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences SPSS Version 23.0(IBM Corp.,Armonk,NY,USA).Thelevel of signif icancewasset at p≤0.05.

Table1Characteristicsof thestudy participants(n=407).

3.Results

A total of 39 women with f ibromyalgia were not previously diagnosed,99 did not meet the 1990 ACR criteria,1 had severe cognitiveimpairment,and 14 did not meet theage criteria.Men with f ibromyalgia were not included in the current study owing to the small sample(n=21).A total of 17 participants did not agree to wear the accelerometer,and data from 3 participants werelost owingto accelerometer malfunction.A total of 17 participants did not meet the accelerometer criteria(insuff icient wear time or incomplete sleep diaries),and 28 did not return completed questionnaires.The f inal sample size included in the analysis was 407 women with f ibromyalgia.Patients'sociodemographic and clinical characteristicsareshown in Table1.

Partial correlations of PA intensity levels and sedentary time with HRQoL are presented in Table 2.Light PA wassignif icantly associated with physical functioning,bodily pain,vitality,and social functioning(rpartialbetween 0.11 and 0.20,all p≤0.05).Moderate PA and MVPA wereboth signif icantly associated with physical functioning,physical role,vitality,social functioning,and physical component(rpartialbetween 0.10 and 0.22,all p≤0.05).Sedentary time was inversely associated with all dimensions of HRQoL(rpartialbetween-0.24 and-0.11,all p≤0.05),except for general health,emotional role,and mental health.

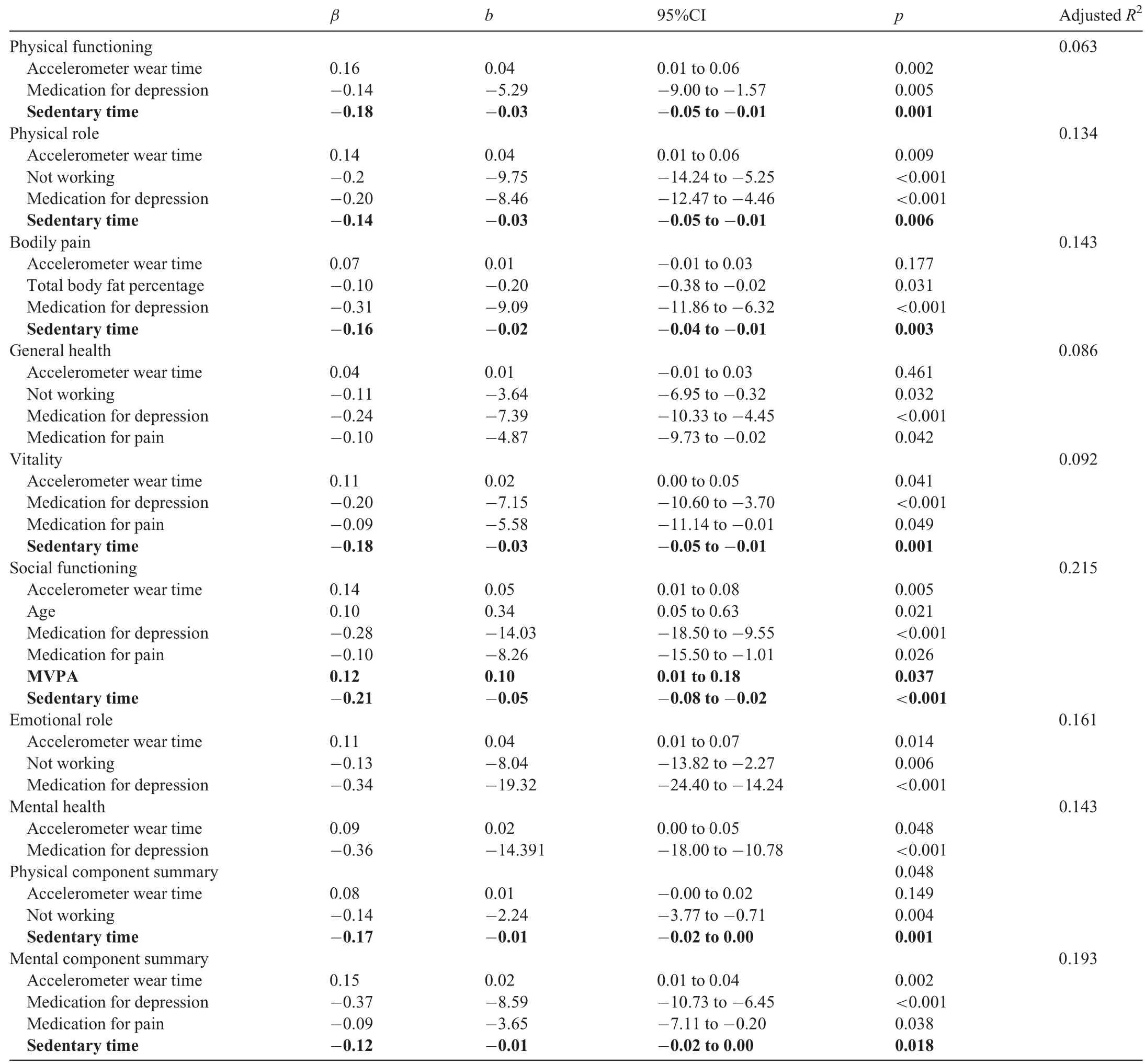

The regression model between PA intensity levels and sedentary time,and SF-36 dimensions,as well as the physical and mental health component summary score(physical and mental health),are shown in Table3.MVPA wasthe only PA intensity level independently associated with HRQoL,specif ically with social functioning(b=0.10,p=0.037).Sedentary time was independently associated with physical functioning (b=-0.03),physical role(b=-0.03),bodily pain(b=-0.02),vitality(b=-0.03),social functioning(b=-0.05),and the physical(b=-0.01)and mental(b=-0.01)component summary score(all p<0.05).

Table2 Partial correlationsof PA intensity levelsand sedentary behavior with HRQoL(n=407).

Fig.1 shows the differences in the dimensions of HRQoL in women with f ibromyalgia meeting(n=86)vs.not meeting(n=321)the current American PA recommendations.Multivariate analysis of covariance analysis showed no signif icant differences between the 2 groupsfor global HRQoL(Hottelling T2:F(8,391)=0.027;p=0.239).In further analysis for each dimension,patients who met the current PA recommendations presented better scores in bodily pain(95%conf idence interval(CI):21.3-27.2 vs.18.9-21.9;p=0.023)and social functioning (95%CI:43.9-44.8 vs.39.8-44.8;p=0.024)dimensions than those who did not meet the current PA recommendations.

Table3Modelsof regression coeff icientsassessing theassociation of PA intensity levelsand sedentary timewith HRQoL(n=407).

The supplementary material includes a replication of all analysesusing the modif ied 2010 ACRpreliminary criteria for diagnosis.Overall,both analyses showed similar results except for a lack of association between sedentary time and physical role,bodily pain,and mental health component when using the modif ied 2010 ACRcriteria.

4.Discussion

The current study showed that light PA and MVPA(positively)and sedentary time(negatively)are associated with different dimensions of HRQoL in women with f ibromyalgia. MVPA intensity level and sedentary time were independently associated with HRQoL dimensions(except for general health,emotional role,and mental health).Participants meeting the current PA recommendations showed better scores in bodily pain and social functioning dimensions of HRQoL than those not meeting the current PA recommendations.Our f indings suggest that patients with f ibromyalgia should be encouraged to reducesedentary timeand increasetheir PA levels.

Fig.1.Means(95%conf idenceinterval)of scoreson the36-item Short-Form Health Survey(SF-36)for each dimension in patientsmeeting(n=86)and not meeting(n=321)thecurrent physical activity(PA)recommendations.Differencesbetween groups were studied using multivariableanalysis of covariance with sociodemographic variables(marital status,occupational status,and education level),total body fat percentage,drug consumption,and accelerometer wear timeentered ascovariates,Hottelling T2:F(8,391)=0.027;p=0.239.*p<0.05.

Diverse intervention studies have suggested that PA is effective for improving symptomatology and HRQoL in patients with f ibromyalgia.18-20However,as far as we know,only 2 previous studies have tested the link between total PA and patients'perception of health status.7,8Sa~nudo et al.7found that patients who reported a moderate level of total PA presented better physical function and general health.Culos-Reed and Brawley8also found evidence that the physical component of HRQoL wasindependently related with ahigher frequency of total PA.Overall,our results concur with previous research,but this is the f irst study supporting the relation of PA with HRQoL using objective measurements of PA in a large and geographically representativesample of women with f ibromyalgia.The specif ic relationship between PA intensity levels and HRQoL in the general populations remains controversial.Although some studies have shown that the regular participation in high-intensity levels of PA is related to better HRQoL in women,38othersstudies have suggested that participation in high-intensity PA for extended periods might result in poorer HRQoL.39In the present study,when PA intensity levels were studied individually,we observed that light,moderate,and MVPA were correlated with different domains of HRQoL.However,MVPA was the only PA intensity level that showed signif icant associationswith HRQoL,independent of light PA and sedentary time.This f inding agrees with recommendations to increase MVPA levels to promote health improvements.10Complementing prior literature demonstrating that increasing time in MVPA was effective to reduce f ibromyalgia impact,18our results also demonstrated that greater time in MVPA isrelated to lessinterference with social activitiesowing to health status.

In line with prior studies in patients with arthritis,13,14we observed that patients who met the PA recommendations had overall better HRQoL,although multivariableanalysisof covariance analyses only showed signif icant differences in the bodily pain and social function domains.Accumulating MVPA for a reduced reported pain partially contrasts with previous studies showing the benef icial role of PA of low and moderate intensity for pain modulation,16interference,20and intensity19in patients with f ibromyalgia.However,it is also noteworthy that light PA was the only PA intensity level associated with better scores in the bodily pain domain in the correlation analyses.Therefore,although alink between PA and pain seemsto exist,40thedifferences in accelerometry devices,cut-points,and tools to assess pain might partly explain the discrepancies when establishing an adequateintensity of PA to promotepain benef its.

Therelationship found in thepresent study between PA and HRQoL iscomplex and might beexplained through intermediate factors.Self-eff icacy can be considered a consequence of PA but might also be a potential mediator between PA and HRQoL.41Positive changes in others'constructs related to mental health(depression,fatigue,social support,mood,42affect,or self-esteem43)havebeen suggested to mediate in the pathway between PA and HRQoL in previous populationbased studies as well.More closely related to the physical component,participation in PA tends to be associated with benef its such as reduction of cardiovascular risk factors,12improved sleep quality,improved f itness level,and reduced functional limitations.10Although this indirect relationship hasbeen grounded theoretically in previousresearch,theintermediate role of the aforementioned factors among patients with f ibromyalgiaisyet to beelucidated.

Thisstudy also f ills a gap in the literature by evidencing an inverse relationship of objectively measured sedentary time with HRQoL independent of PA in women with f ibromyalgia.The strongest association of sedentary time was observed with the social function dimension.The passive nature of different sedentary activities(e.g.,watching television or sitting at the computer)isthought to beaccompanied by decreased communication and poor social networking.44Becausesocial isolation concerns are frequently reported by these patients,preventing prolonged sedentary activities and moving toward a less sedentary lifestyle may positively inf luence this construct of health.Mechanismsthat explain thedeleteriousrelationship of sedentary behavior and HRQoL have been less studied than thoseidentif ied with PA.Nevertheless,someadaptationsnegatively related to the mental component of HRQoL,such as stress,anxiety,depression,and mental disorders,have been connected to sustained sedentary time.23Impaired pain regulation related to sedentary behavior15could additionally explain detriments in patients'reported health status.Furthermore,prolonged sedentary time compromises cardiometabolic health,leading to increased cardiovascular risk,hypertension,and diabetes.22The fact that sedentary behavior is higher in patients with f ibromyalgia,9added to the association found between sedentary time and HRQoL independent of PA,displaysthe importance of this behavior asa target for health promotion efforts in these patients.Therefore,motivating women with f ibromyalgiato becomelesssedentary seemsto beavaluable strategy,because this behavior would likely result in increases in light PA behaviors,which also presented positive correlations with HRQoL in the current study,as well as overall symptomsin previous studies.15,19,45

The absence of a gold standard to identify f ibromyalgia makestheevaluation of the disease diff icult and controversial.Since the f irst diagnosis was released in 1990,26this criterion hasbeen widely used in prior literatureand remainsthecurrent off icial criteriafor the diagnosisof f ibromyalgia.A new understanding of the concept of f ibromyalgia arose with the modif ied ACR 2010 criteria,32giving greater emphasis to symptoms and dropping the tender point assessment from 1990.The 2011 criteria have some limitations,however,such as the misclassif ication of patients who do not have generalized pain but have regional pain syndromes.46It is therefore possible that using different diagnostic criteria changes the f ibromyalgia case def initions and consequently might imply slight modif ications in study results.To understand the robustness of our results across different classif ication criteria,themodif ied 2010 criteria(see the supplementary material)were also used.In our analyses,changes in results related to physical role and bodily pain dimensions,as well as the mental health component,were observed,resulting in a lack of association(but having borderline signif icance)when using the modif ied 2010 criteria.These discrepancies were expected because the 2010 symptom severity scale is closely related to those dimensionsof health by assessing diff iculty in thinking or remembering,pain or cramps in the lower abdomen,depression,and headache.

The present study has some limitations that must be acknowledged.Because our results are derived from a crosssectional study,theassociationsfound cannot beexplained via a causal pathway:although PA might improve HRQoL,it is possible that individuals with impaired HRQoL are less likely to participate in PA behavior.Additionally,owing to the large number of factors related to HRQoL,it isdiff icult to ascertain the true association between PA intensity levels and sedentary time with HRQoL.Given that only women took part in this study,future studies should investigate whether these associations also occur in men.Despite these limitations,this study has several strengths,including the use of accelerometers,which allowed usto objectively quantify intensitiesof PA and time spent in sedentary activities.Furthermore,we assessed a relatively large sample size of women with f ibromyalgia who were representative of southern Spain(Andalusia).24We also attempted to enhance the robustnessof our analyses by adjusting for areasonablenumber of potential confounders.

5.Conclusion

This study shows that all PA intensity levels(positively)and sedentary time(negatively)were individually correlated with better scores in different domains of HRQoL.However,among the different PA intensity levels,only MVPA showsan independent association with HRQoL,specif ically with the social functioning domain.Moreover,patients who meet the American PA recommendations present signif icantly better scores in bodily pain and social functioning domains.Interestingly,sedentary timeisalso independently and inversely associated with the physical functioning,physical role,bodily pain,vitality,social functioning,physical component,and mental component dimensions of HRQoL.The effects on HRQoL of strategies aimed at reducing sedentary time,which results in greater light PA and eventually leadsto engagement in MVPA among thispopulation,need to befurther evaluated.

Acknowledgment

We would like to thank all the members involved in the f ieldwork,especially members from CTS-1018 research group.We also gratefully acknowledge all study participants for their collaboration.This study was supported by the Spanish Ministries of Economy and Competitiveness(I+D+i DEP2010-15639; I+D+I DEP2013-40908-R,BES-2014-067612)and the Spanish Ministry of Education(FPU 13/01088;FPU 15/00002).

Authors'contributions

BGC carried out the analysis and the interpretation of data and drafted themanuscript;VSJcontributed to study conception and design,acquisition of data,analysis and interpretation of data,and drafted the manuscript;FEL contributed to study conception and design,acquisition of data,and drafted the manuscript;ICAG contributed to study conception and design,acquisition of data,and drafted the manuscript;ASM contributed to study conception and design,acquisition of data,and drafted the manuscript;MBC,MHC,and PAM c ontributed to acquisition of data and drafted the manuscript;MDF contributed to study conception and design,acquisition of data,analysis and interpretation of data,and drafted the manuscript.All authors have read and approved the f inal version of the manuscript,and agree with theorder of presentation of theauthors.

Competinginterests

The authorsdeclarethat they have no competing interests.

Supplementarymaterials

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found,in theonlineversion,at doi:10.1016/j.jshs.2018.07.001.

References

1.Rahman A,Underwood M,Carnes D.Fibromyalgia.BMJ 2014;348:g1224.doi:10.1136/bmj.g1224.

2.Verbunt JA,Pernot DH,Smeets RJ.Disability and quality of life in patients with f ibromyalgia.Health Qual Life Outcomes 2008;6:8.doi:10.1186/1477-7525-6-8.

3.Macfarlane GJ,Kronisch C,Dean LE,Atzeni F,H¨auser W,Flub E,et al.EULAR revised recommendations for the management of f ibromyalgia.Ann Rheum Dis2017;76:318-28.

4.Jones KD,Liptan GL.Exercise interventions in f ibromyalgia:clinical applications from the evidence.Rheum Dis Clin North Am2009;35:373-91.

5.Bize R,Johnson JA,Plotnikoff RC.Physical activity level and healthrelated quality of lifein thegeneral adult population:asystematic review.Prev Med 2007;45:401-15.

6.Davies CA,Vandelanotte C,Duncan MJ,van Uffelen JGZ.Associations of physical activity and screen-time on health related quality of life in adults.Prev Med 2012;55:46-9.

7.Sa~nudo JI,Corrales-S′anchez R,Sa~nudo B.Physical activity levels,quality of lifeand incidenceof depression in older women with Fbromyalgia(Nivel de actividad f′ısica,calidad de vida y niveles dedepresi′on en mujeres mayorescon Fbromialgia).Escritos Psicol 2013;6:53-60.[in Spanish].

8.Culos-Reed SN,Brawley LR.Fibromyalgia,physical activity,and daily functioning:the importance of eff icacy and health-related quality of life.Arthritis Care Res2000;13:343-51.

9.Nijs J,Roussel N,Van Oosterwijck J,De Kooning M,Ickmans K,Struyf F,et al.Fear of movement and avoidancebehaviour toward physical activity in chronic-fatigue syndrome and f ibromyalgia:state of the art and implicationsfor clinical practice.Clin Rheumatol 2013;32:1121-9.

10.Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee.Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee report,2008.Washington,DC:U.S.Department of Health and Human Services;2008.

11.Segura-Jimenez V,Alvarez-Gallardo IC,Estevez-Lopez F,Soriano-Maldonado A,Delgado-Fernandez M,Ortega FB,et al.Differences in sedentary time and physical activity between female patients with f ibromyalgia and healthy controls:the al-Andalus project.Arthritis Rheumatol 2015;67:3047-57.

12.Acosta-Manzano P,Segura-Jim′enez V,Est′evez-L′opez F,′Alvarez-Gallardo IC,Soriano-Maldonado A,Borges-Cosic M,et al.Do women with f ibromyalgiapresent higher cardiovascular diseaserisk prof ilethan healthy women?Theal-Andalusproject.Clin Exp Rheumatol 2017;35:61-7.

13.Austin S,Qu H,Shewchuk RM.Association between adherence to physical activity guidelines and health-related quality of lifeamong individuals with physician-diagnosed arthritis.Qual Life Res2012;21:1347-57.

14.Abell JE,Hootman JM,Zack MM,Moriarty D,Helmick CG.Physical activity and health related quality of life among people with arthritis.J Epidemiol Community Health 2005;59:380-5.

15.Ellingson LD,Shields MR,Stegner AJ,Cook DB.Physical activity,sustained sedentary behavior,and pain modulation in women with f ibromyalgia.JPain 2012;13:195-206.

16.McLoughlin MJ,Stegner AJ,Cook DB.The relationship between physical activity and brain responses to pain in f ibromyalgia.JPain 2011;12:640-51.

17.Segura-Jimenez V,Borges-Cosic M,Soriano-Maldonado A,Estevez-Lopez F,Alvarez-Gallardo IC,Herrador-Colmenero M,et al.Association of sedentary time and physical activity with pain,fatigue,and impact of f ibromyalgia:the al-Andalus study.Scand JMed Sci Sports 2017;27:83-92.

18.Kaleth AS,Saha CK,Jensen MP,Slaven JE,Ang DC.Moderate-vigorous physical activity improveslong-term clinical outcomeswithout worsening pain in f ibromyalgia.Arthritis Care Res(Hoboken)2013;65:1211-8.

19.Fontaine KR,Conn L,Clauw DJ.Effectsof lifestylephysical activity on perceived symptomsand physical function in adultswith f ibromyalgia:resultsof arandomized trial.Arthritis Res Ther 2010;12:R55.doi:10.1186/ar2967.

20.Kaleth AS,Slaven JE,Ang DC.Does increasing steps per day predict improvement in physical function and pain interference in adults with f ibromyalgia?Arthritis Care Res(Hoboken)2014;66:1887-94.

21.Barnes J,Behrens TK,Benden ME,Biddle S,Bond D,Brassard P,et al.Letter to the editor:standardized use of the terms“sedentary”and“sedentary behaviours”.Appl Physiol Nutr Metab Appl Nutr Metab 2012;37:540-2.

22.Owen N,Healy GN,Matthews CE,Dunstan DW.Too much sitting:the population-health science of sedentary behavior.Exerc Sport Sci Rev 2010;38:105.doi:10.1097/JES.0b013e3181e373a2.

23.Ellingson LD,Kuffel AE,Cook DB.Active and sedentary behavior patterns predictmental healthand quality of lifein healthy women:2885.Med Sci Sport Exerc 2011;43(Suppl.1):S817.doi:10.1249/01.MSS.0000402277.44495.62.

24.Segura-Jim′enez V,′Alvarez-Gallardo IC,Carbonell-Baeza A,Aparicio VA,Ortega FB,Casimiro AJ,et al.Fibromyalgia has a larger impact on physical health than on psychological health,yet both are markedly affected:theal-Andalusproject.Semin Arthritis Rheum2015;44:563-70.

25.Folstein MF,Folstein SE,McHugh PR.“Mini-mental state”:a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patientsfor the clinician.JPsychiatr Res1975;12:189-98.

26.Wolfe F,Smythe HA,Yunus MB,Bennett RM,Bombardier C,Goldenberg DL,et al.The American College of Rheumatology 1990 criteria for theclassif ication of f ibromyalgia.Arthritis Rheum1990;33:160-72.

27.Alonso J,Prieto L,Anto JM.The Spanish version of the SF-36 Health Survey(the SF-36 health questionnaire):an instrument for measuring clinical results.Med Clin(Barc)1995;104:771-6.

28.Aguilar-Far′ıas N,Brown WJ,Peeters GM.ActiGraph GT3X+cut-points for identifying sedentary behaviour in older adults in free-living environments.JSci Med Sport 2014;17:293-9.

29.Sasaki JE,John D,Freedson PS.Validation and comparison of ActiGraph activity monitors.JSci Med Sport 2011;14:411-6.

30.Choi L,Ward SC,Schnelle JF,Buchowski MS.Assessment of wear/nonwear time classif ication algorithms for triaxial accelerometer.Med Sci Sports Exerc 2012;44:2009-16.

31.Troiano RP,Berrigan D,Dodd KW,Masse LC,Tilert T,McDowell M.Physical activity in the United Statesmeasured by accelerometer.Med Sci Sports Exerc 2008;40:181-8.

32.Wolfe F,Clauw DJ,Fitzcharles MA,Goldenberg DL,Katz RS,Mease P,et al.The American College of Rheumatology preliminary diagnostic criteria for f ibromyalgia and measurement of symptom severity.Arthritis Care Res2010;62:600-10.

33.Wolfe F,Clauw DJ,Fitzcharles M,Don L,H¨auser W,Katz RS,et al.Fibromyalgia criteria and severity scales for clinical and epidemiological studies:a modif ication of the ACR preliminary diagnostic criteria for f ibromyalgia.JRheumatol 2011;38:1113-22.

34.Segura-Jim′enez V,Aparicio VA,′Alvarez-Gallardo IC,Soriano-Maldonado A,Est′evez-L′opez F,Delgado-Fern′andez M,et al.Validation of the modif ied 2010 American College of Rheumatology diagnostic criteria for f ibromyalgia in a Spanishpopulation.Rheumatology(Oxford)2014;53:1803-11.

35.Segura-Jimenez V,Aparicio VA,Alvarez-Gallardo IC,Carbonell-Baeza A,Tornero-Quinones I,Delgado-Fernandez M.Does body composition differ between f ibromyalgiapatientsand controls?Theal-Andalusproject.Clin Exp Rheumatol 2015;33(Suppl.1):S25-32.

36.Malavolti M,Mussi C,Poli M,Fantuzzi AL,Salvioli G,Battistini N,et al.Cross-calibration of eight-polar bioelectrical impedance analysis versus dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry for the assessment of total and appendicular body composition in healthy subjects aged 21-82 years.Ann Hum Biol 2003;30:380-91.

37.Lee JW,Lee KE,Park DJ,Kim SH,Nah SS,Lee JH,et al.Determinants of quality of life in patients with f ibromyalgia:a structural equation modeling approach.PLoSOne 2017;12:e0171186.doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0171186.

38.Morimoto T,Oguma Y,Yamazaki S,Sokejima S,Nakayama T,Fukuhara S.Gender differences in effects of physical activity on quality of life and resourceutilization.Qual Life Res2006;15:537-46.

39.Brown DW,Brown DR,Heath GW,Balluz L,Giles WH,Ford ES,et al.Associations between physical activity dose and health-related quality of life.Med Sci Sport Exerc 2004;36:890-6.

40.Galloway DA,Laimins LA,Division B,Hutchinson F.How doesphysical activity modulatepain?Pain 2016;158:87-92.

41.McAuley E,Doerksen SE,Morris KS,Motl RW,Hu L,Wojcicki TR,et al.Pathways from physical activity to quality of life in older women.Ann Behav Med 2008;36:13-20.

42.Motl RW,McAuley E,Snook EM,Gliottoni RC.Physical activity and quality of life in multiple sclerosis:intermediary roles of disability,fatigue,mood,pain,self-eff icacy and social support.Psychol Health Med 2009;14:111-24.

43.Elavsky S,McAuley E,Motl RW,Konopack JF,Marquez DX,Hu L,et al.Physical activity enhances long-term quality of life in older adults:eff icacy,esteem,and affectiveinf luences.Ann Behav Med 2005;30:138-45.

44.Kraut R,Patterson M,Lundmark V,Kiesler S,Mukopadhyay T,Scherlis W.Internet paradox—a social technology that reducessocial involvement and psychological well-being?Am Psychol 1998;53:1017-31.

45.Segura-Jim′enez V,Soriano-Maldonado A,Est′evez-L′opez F,′Alvarez-Gallardo IC,Delgado-Fern′andez M,Ruiz JR,et al.Independent and joint associations of physical activity and f itness with f ibromyalgia symptoms and severity:theal-′Andalusproject.JSports Sci2017;35:1565-74.

46.Wolfe F,Clauw DJ,Fitzcharles MA,Goldenberg DL,H¨auser W,Katz RL,et al.2016 revisions to the 2010/2011 f ibromyalgia diagnostic criteria.Semin Arthritis Rheum2016;46:319-29.

Journal of Sport and Health Science2019年3期

Journal of Sport and Health Science2019年3期

- Journal of Sport and Health Science的其它文章

- Corrigendum Corrigendum to“Denervated muscleextract promotesrecovery of muscle atrophy through activation of satellite cells.An experimental study”[JSport Health Sci8(2019)23-31]

- Original article Group dynamicsmotivation to increaseexerciseintensity with a virtual partner

- Original article Adolescents'personal beliefsabout suff icient physical activity aremore closely related to sleep and psychological functioning than self-reported physical activity:A prospectivestudy

- Original article Parents'participation in physical activity predicts maintenance of some,but not all,types of physical activity in offspring during early adolescence:A prospective longitudinal study

- Original article Determination of functional f itness age in women aged 50 and older

- Original article Classif ication of higher-and lower-mileage runners based on running kinematics