Original article Neuromuscular fatigue and recovery prof iles in individuals with intellectual disability

Rih Borji *,Firs Zghl Nidhl Zrrouk Vincent Mrtin ,Soni Shli Hithem Rei

a Research Unit Education,Motor Skills,Sports and Health(EM2S,UR15JS01),Higher Institute of Sport and Physical Education of Sfax,University of Sfax,Sfax 3000,Tunisia

b Laboratory of Metabolic Adaptations to Exercise in Physiological and Pathological Conditions,Blaise Pascal University,Clermont-Ferrand 63000,France

Abstract Purpose:This study aimed to explore neuromuscular fatigue and recovery prof ilesin individuals with intellectual disability(ID)after exhausting submaximal contraction.Methods:Ten men with ID were compared to 10 men without ID.The evaluation of neuromuscular function consisted in brief(3 s)isometric maximal voluntary contraction(IMVC)of thekneeextension superimposed with electrical nervestimulation before,immediately after,and during 33 min after an exhausting submaximal isometric task at 15%of the IMVC.Force,voluntary activation level(VAL),potentiated twitch(Ptw),and electromyography(EMG)signals were measured during IMVC and then analyzed.Results:Individualswith IDdeveloped lower baseline IMVC,VAL,Ptw,and RMS/Mmax ratio(root-mean-squarevaluenormalized to themaximal peak-to-peak amplitude of the M-wave)than controls(p<0.05).Nevertheless,the time to task failure was signif icantly longer in ID vs.controls(p<0.05).The2 groupspresented similar IMVCdeclineand recovery kineticsafter thefatiguing exercise.However,individualswith IDpresented higher VAL and RMS/Mmax ratio declines but lower Ptw decline compared to those without ID.Moreover,individuals with ID demonstrated a persistent central fatigue but faster recovery from peripheral fatigue.Conclusion:These differences in neuromuscular fatigue prof iles and recovery kinetics should be acknowledged when prescribing training programs for individuals with ID.2095-2546/©2019 Published by Elsevier B.V.on behalf of Shanghai University of Sport.Thisisan open accessarticleunder the CCBY-NC-ND license(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

Keywords:Central fatigue;Intellectual disability;Neuromuscular fatigue;Peripheral fatigue;Sustained sub-maximal exercise;Twitch interpolation technique

1.Introduction

Exercise related neuromuscular fatigue is def ined as an exercise-related decrease in the maximal voluntary force or power of a muscle or of a muscle group.This decrease is generally associated with an increase in the perceived effort necessary to exert thedesired force.1It can beestimated by the maximal force or power2decline or by the inability to sustain a required force level.3In this context,it has been demonstrated that individuals with low maximal force level such as women,theelderly,or children presentlonger timeto task failureduring sub-maximal exercises than individuals with high maximal forcelevel.4-6Neuromuscular fatigueisgenerally considered to betask-dependent.1Specif ically,exerciseintensity and duration determine the contribution of central and peripheral factors to neuromuscular fatigue.7Therefore,ithasbeenwell documented that muscle fatigue induced by sustained lower intensity contractions induced central fatigue rather than peripheral fatigue.8,9Neuromuscular fatigue depends also on the initial voluntary activation level(VAL)10that describes the neural drive of a muscle during voluntary contractions.11It has been demonstrated that individuals with poor ability to achieve full activation during a maximal voluntary contraction develop less peripheral fatigue10and longer endurance time during a fatiguing protocol.12

It seems to be interesting to explore the neuromuscular fatigue prof ile of individuals with intellectual disability(ID)who exhibit lower VAL whencompared to general population.13IDischaracterized by signif icantlimitationsboth inintellectual functioning and in adaptive behavior,which covers a range of everyday social and practical skills.14Generally,a full score at an intellectual quotient(IQ)of around 70 to 75 indicates that the individual presents an ID.Moreover,these individuals present generally poor physical f itness and motor skills compared to individuals with typical development.15,16Importantly,while it is well known that individuals with ID demonstrate lower maximal force17-19than individuals with typical development,littleisknown about their neuromuscular fatigue prof ile.Zafeiridis et al.,19reported a lower force decrement and a slower fatigue development in these individuals during maximal repeated knee extensions and f lexions compared to controls.These authors found that individuals with ID presented a lower blood lactate accumulation after the fatiguing exercise.19Because it has been found that the increased accumulation of by-products(lactate,H+)of anaerobic metabolism impairs the excitation-contraction coupling and cross-bridges formation,20these authors suggested that the lower reliance on glycolytic metabolismfor energy production in individualswith ID,as suggested by their lower lactate concentration,may possibly explain their lower muscle fatigue compared to controls.19Conversely,we previously reported a greater force and electromyography(EMG)activity declines in individuals with ID compared to individuals without ID after maximal repeated knee extensions and f lexions.17We suggested that the higher strength decline observed in individuals with ID after this fatiguing exercisecould berelated to agreater neural activation def iciency probably resulting from the central nervous system anomalies characterizing these individuals.21,22Nevertheless,direct evidence isstill lacking to support thisassumption,as no study has measured the VAL after a fatiguing exercise in individuals with ID.Beyond the magnitude of neuromuscular fatigue,the ability to recover from a fatiguing task may have important implications in daily-life activities,aswell as during occupational activities in individuals with ID.19To date,the recovery ability of these individuals after a fatiguing exercise has never been explored.

Therefore,theaim of our study wasto investigatetheability to sustain exhausting sub-maximal isometric contraction in individuals with ID compared to those with typical development and to explore the magnitude,the neuromuscular fatigue origin,and the subsequent recovery in these individuals.We hypothesized that individuals with ID would present a neuromuscular fatigue prof ile,as well as a recovery kinetic,that differs from those of individuals with typical development.

2.Methods

2.1.Participants

Thesamplepopulation consisted of 20 sedentary adultswho had similar socioeconomic statusand ethnicity.Tenmenwith ID(age:23.1±2.7 years;height:1.7±0.1 m;body mass:77.9±8.3 kg)participated in thestudy.All participantswith ID suffered fromamild IDwithan IQ(IQ=60.0±2.7)determined by the Wechsler adultintelligencescale(WAIS-IV)test23elaborated by the educational center psychologist.Participants with ID were recruited randomly from the National Union of Aid to Mental Insuff iciency where they took part in a physical educationsessiononceaweek.Thesampledid notincludeindividuals with Down Syndrome or with multiple disabilities.The informed written consent for the individuals with ID was provided by their parents or legal guardians.The control group consisted of 10sedentary menwithout ID(age:25.2±2.7years;height:1.7±0.1 m;body mass:75.3±9.2 kg),who practiced only leisure physical activities.The participants without ID provided written consent.The study excluded individuals with metabolic diseases,as well as musculoskeletal,cardiac,and respiratory system diseasesin order to avoid potential inf luence of health factorson the outcome of the experiment.

Thestudy wasconducted in accordancewith the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committeeof the National Centreof Medicineand Sciencesin Sport of Tunisia.

2.2.Study design

A familiarization session was performed 3 days before the experiment in order to familiarize participants with the experimental procedures.The experiment consisted of baseline measurements,followed by an exhausting exercise performed at 15%of isometric maximal voluntary contraction(IMVC),and follow-up measurements to describe the recovery prof ile after the exercise.The baseline measurements consisted of 3 brief(3 s)IMVCsof thekneeextensorssuperimposed with electrical stimulations.After theexercise,12 brief(3 s)IMVCssuperimposed with electrical stimulations were repeated every 3 min.The testing session was preceded by a warm-up consisting of several sub-maximal knee extensions(12-15 contractions)at a freely chosen intensity.

To evaluate the central and peripheral factors of the force production,electrical stimulations were delivered to the femoral nerve during the IMVC and 3 s after the contraction cessation.Force and EMG signals were measured during IMVC.To excludetheconfounding effectof fatigueinduced by repeated muscular contractions,IMVCtrialswereseparated by a 3-min recovery period(Fig.1).

2.3.Testing procedures and instrumentation

2.3.1.Force measurement

Fig.1.Schematic representation of the experimental protocol.To evaluate exercise-induced fatigue and recovery,3 and then 12 repeated isometric maximal voluntary contractions(IMVC)superimposed and followed by peripheral nerve electrical stimulation(PNS)were performed before(pre-EX)and after fatiguing exercise(post-EX),respectively.

During testing,the participants were seated on an isometric dynamometer(Good Strength,Metitur,Finland)equipped with a cuff attached to a strain gauge.This cuff was adjusted~2 cm above the lateral malleolus using a Velcro strap.The participants stabilized themselves by grasping handles on the side of thechair during contractions.Safety beltswerestrapped across the chest,thighs,and hips to avoid lateral,vertical,and frontal displacements.All measurements were taken from the participant's dominant leg,with the hip and knee angles set at 90°from full extension(0°).All participantsin our study presented theright leg as the dominant leg(determined by the leg used to kick aball).Strong verbal encouragementswereprovided to the participants during the IMVC.

2.3.2.EMG recordings

The EMGsignalsof thevastuslateralis(VL),vastusmedialis(VM),and rectusfemoris(RF)muscleswererecorded using bipolar silver chloridesurfaceelectrodes(Blue Sensor N-00-S,Ambu,Denmark)during IMVC and stimulations.Following the surface EMG for the noninvasive assessment of muscles(SENIAM)recommendations,24the recording electrodes were taped lengthwise on the skin over the muscle belly,with an inter-electrode distance of 20 mm and the reference electrode wasattached to thepatella.Thesampling frequency was2 kHz.Low impedance(Z<5 kΩ)at the skin-electrode surface was obtained by shaving,abrading theskinwiththinsand paper,and cleaning with alcohol.EMGsignalswere amplif ied(Octal Bio Amp ML 138;ADInstruments,Bella Vista,Australia)with a bandwidth frequency ranging from 10 Hz to 1000 Hz(common mode rejection ratio>96 dB,gain=1000)and simultaneously digitized together with the force signals using an acquisition card(Powerlab 16SP;ADInstruments)and Labchart 7.0 software(ADInstruments).The IMVCforcewasdetermined asthe peak force reached during maximal efforts.The root mean square(RMS)values of the VL,VM,and RF were calculated during the IMVC trials over a 0.5-s period after the force had reached a plateau and before the superimposed stimulation were evoked.This RMS value was then normalized to the maximal peak-to-peak amplitude of the M-wave(RMS/Mmax).

2.3.3.Peripheral nerve stimulation

The femoral nerve was stimulated percutaneously with a single square-wave stimulus of 1-ms duration with maximal voltage of 400 V delivered by a constant current stimulator(Digitimer Limited,Hertfordshire,UK).The cathode(selfadhesiveelectrode:Ag-AgCl,10-mm diameter)waspositioned f irmly in the femoral triangle.The anode,a 10×5-cm selfadhesivestimulation electrode(Compex Médical SA,Ecublens,Switzerland)wasplaced midway between thegreater trochanter and theiliac crest.Optimalstimulationintensity wasdetermined from M-wave and force measurements before each testing session.The stimulation intensity was increased by 5 mA until there was no further increase in peak twitch force(i.e.,the highest value of the knee extension twitch force was reached)and in theconcomitant VL,VM,and RFpeak-to-peak M-wave amplitude(Mmax).Duringthesubsequenttesting procedures,the intensity was set to 150%of the optimal intensity to overcome the potential confounding effect of axonal hyperpolarization.25

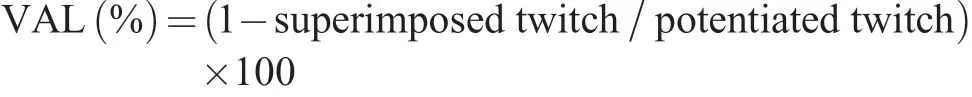

Twoelectrical nervestimulationsweredelivered atthelevel of the femoral nerve.The f irst stimulation,delivered during the IMVC,was named the superimposed twitch,and the second stimulation,delivered 3 s after the IMVC,was named the potentiated twitch(Ptw).This delay provided the opportunity to obtain apotentiated mechanical responseand so reducethevariability involuntary activation.26Theamplitudeof thepotentiated twitch was measured to ref lect the muscle capacity to produce forceduring theelectrical stimulation.Themagnitudeof the Ptw decline ref lects the magnitude of peripheral fatigue.20Both the superimposed and the potentiated twitch amplitudesallowed the quantif ication of VAL as proposed by Merton27as follows:

where superimposed twitch is the amplitude of the twitch evoked with electrical nerve stimulation during IMVC and potentiated twitch is the amplitude of the twitch evoked by a single stimulation delivered 3 s after the end of the IMVC as proposed by Merton.27

2.3.4.Fatiguing exercise

Participants were asked to sustain a low-intensity isometric contraction(15%of the maximal isometric force recorded during pre-exercise)until exhaustion.During theexercise,each participant wasable to visualize forcefeedback and guidelines on a computer screen.The participants were encouraged to maintain the force at the target level as long as possible.Exhaustion wasreached when theparticipantvoluntary stopped the exercise or failed to maintain force at the target level for a duration>5 s.Force and knee extension EMG activities were continuously monitored during theexerciseto providefeedback about force level and EMG activities.

2.4.Statistical analysis

Astheneuromuscular testing involved several sets,valuesof each variable measured during the repetitive trials were averaged as follows:the 3 values issued from the 3 sets performed before exhausting exercise were averaged to compute the baseline(pre-EX)value;3 values were averaged for the 3 sets performed in the recovery period 3 to 9 min after exercise(post-EX 3-9);and 4 values were averaged for the 4 sets performed from 12 to 21 min and from 24 to 33 min after exercise(post-EX 12-21 and post-EX 24-33,respectively).To accurately ref lect the fatigue induced by the sustained contraction,thevariables measured in the set immediately after the exercise(post-EX)were not averaged with thosemeasured in other sets.

Data were analyzed by the Statistica for Windows software(Version 6.0;StatSoft Inc.,Tulsa,OK,USA).Datadistribution normality was conf irmed with the Shapiro-Wilk W-test.Independent sample t testswereexecuted in order to analyzegroup differences for morphologic characteristics(age,height,and body mass),baselinevalues(IMVC,VAL,Ptw,and RMS/Mmax)and thetimeto task failurein theexhausting exercise.All these data(IMVC,VAL,Ptw,and RMS/Mmax)werenormalized to the maximal corresponding values recorded before exercise(%of pre-Ex values).Then the relative values of IMVC,VAL,Ptw,and RMS/Mmaxwere analyzed using a two-way analysis of variance(ANOVA)with repeated-measures(Group×Time).For each statistically signif icant effect of main factor and interaction,a post hoc analysiswasperformed using the LSDFisher test.The decrease rate of IMVC,VAL,and Ptw values after fatigue was evaluated by calculating Delta as:Δ%=100%×(post-EX-pre-EX)/pre-EX).The level of signif icance for all statistical analyses was set at p<0.05.

3.Results

3.1.Baseline values and time to task failure

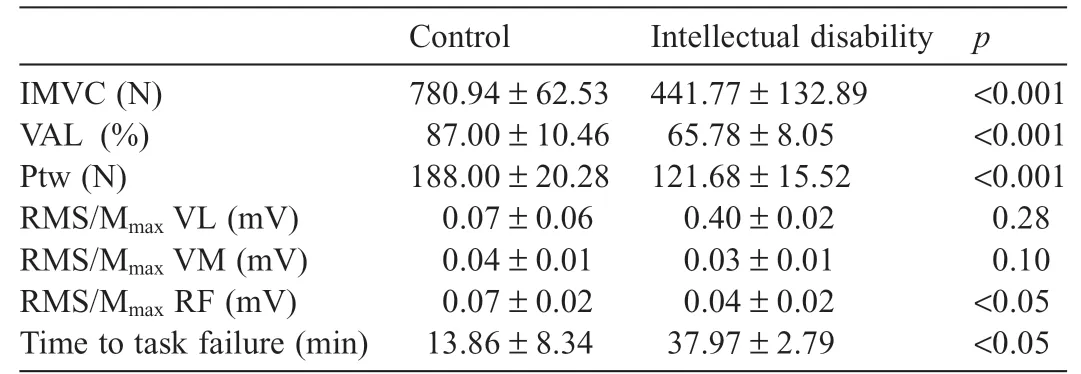

The independent sample t test demonstrated that the ID group showed signif icantly lower IMVC,VAL,and Ptw compared to the control group(p<0.001).Moreover,the independent sample t test revealed that the ID group demonstrated signif icant lower RMS/Mmaxfor the RF muscle(p<0.05).However,no signif icant differences of RMS/Mmaxfor VL(p=0.28)and VM(p=0.10)muscles were revealed between groups.Thetimeto task failureduring thesustained exhausting isometric exercise was signif icantly longer in ID than in the control group(p<0.05)(Table 1).

3.2.Fatigue parameters

3.2.1.IMVC

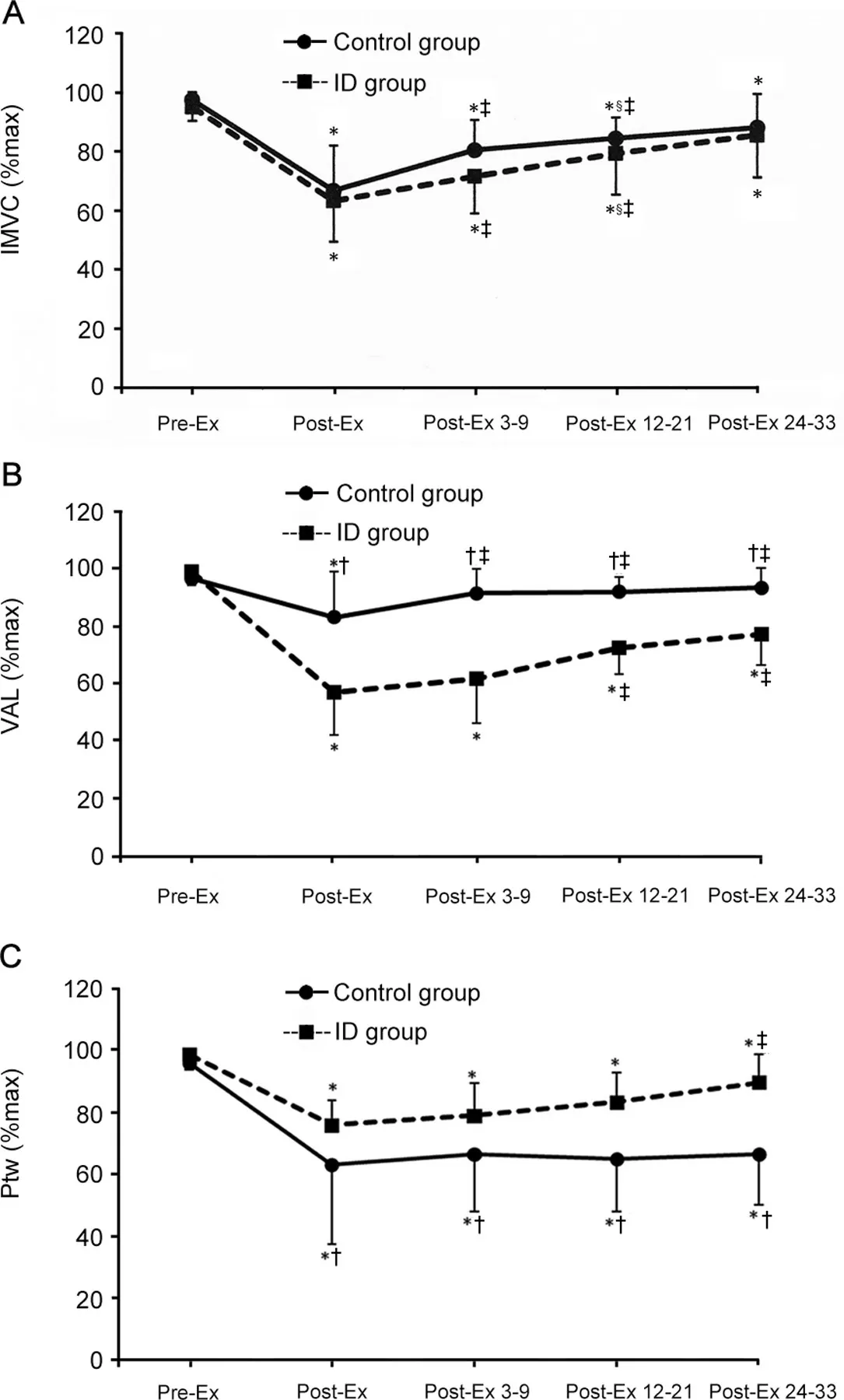

The two-way ANOVA on relative IMVC data indicated a signif icantmain effectof Time(F(4,72)=37.86,p<0.001)and nosignif icantmaineffectof Group(F(1,18)=1.43,p=0.24)or Group×Time interaction(F(4,72)=0.50,p=0.72).The post hoc test showed a signif icant(p<0.05)IMVC decline in both groupsatpost-EX.Moreover,thesesanalysisshowedthat IMVC level increased signif icantly at post-EX 3-9 compared with post-EX indicating the start of recovery for both groups(p<0.05).Therecovery of IMVCcontinued at post-EX 12-21.In fact,IMVCvaluesrecording at post-EX 12-21 weresignif icantly(p<0.05)higher than atpost-EX 3-9 and post-EX group for both groups.However,both groups failed to recover their baseline values at post-EX 24-33 compared to pre-Ex(p<0.05).No signif icant differencewasreported between the2 groupsconcerning IMVCvalues(Fig.2A).

3.2.2.VAL

The two-way ANOVA revealed signif icant main effects of Group(F(1,18)=36.94,p<0.001),Time(F(4,72)=26.74,p<0.001)and Group×Time interaction(F(4,72)=9.81,p<0.001)on relative VAL.Concerning the within-time effect,the post hoc analysis showed that,in the control group,VAL decreased signif icantly(p<0.05)at post-EX and recovered fully to baseline values at post-EX 3-9.Moreover,in the ID group,the post hoc analysis showed that VAL decreased signif icantly at post-EX(p<0.05).Compared to post-EX,a signif icant(p<0.05)increase of VAL was registered at post-EX 12-21.However,at post-EX 24-33 the VAL remained lower(p<0.05)than at pre-EX for both groups(Fig.2B).Regarding the between group effects,the post hoc analysis showed that VAL was signif icantly lower in the ID group compared to the control group at post-EX and throughout the recovery period(p<0.05)(Fig.2B).

Table1Baseline values of IMVC,VAL,Ptw,RMS/Mmax for VL,VM,and RFmuscles and the time to task failure in both groups.

Fig.2.Evolution of the(A)IMVC(%max),(B)VAL(%max),and(C)Ptw(%max)before(pre-EX),immediately after the fatiguing isometric task(post-EX),and during the recovery period(post-EX 3-9,post-EX 12-21,post-EX 24-33)in individuals.*p<0.05,compared with baseline;†p<0.05,compared with ID group;‡p<0.05,compared with post-Ex;§p<0.05,compared with post-EX 3-9.ID=intellectual disability;IMVC=isometric maximal voluntary contraction;post-Ex=post-exercise;post-Ex 3-9=3 sets performed in the recovery period 3 to 9 min after exercise;post-Ex 12-21=4 sets performed from 12 to 21 min after exercise;post-Ex 24-33=4 sets performed from 24 to 33 min after exercise;pre-Ex=pre-exercise;Ptw=potentiated twitch;VAL=voluntary activation level.

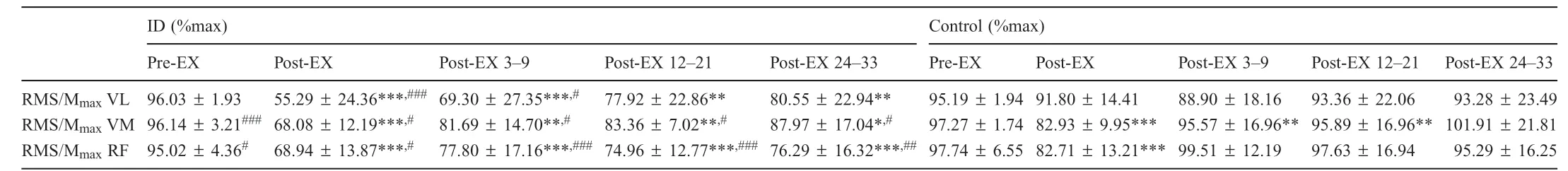

Table2Evolution of the RMS/Mmax valuesof the VL,VM,and RFmusclesin individualswith ID and control group at Pre-EX,Post-EX,and Post-EX 3-9,Post-EX 12-21,Post-EX 24-33 from the exhausting isometric task.

3.2.3.Ptw

The two-way ANOVA analysis of the relative Ptw values revealed signif icant main effects of Group(F(1,18)=7.09,p<0.05),Time(F(4,72)=34.90,p<0.001)and Group×Time interaction(F(4,72)=4.25,p<0.01).Concerning the within-time effects,the post hoc test showed that the Ptw decreased signif icantly(p<0.05)in the control group at post-EX.No recovery of Ptw values was observed in this group through therecovery period.Similarly,in the ID group,the Ptw values decreased signif icantly(p<0.05)at post-EX.However,in this group,these values increased signif icantly(p<0.05)at post-Ex 24-33 compared to post-EX but did not recover to baselinevalues(Fig.2C).Regarding thebetween group effects,the post hoc analysis showed that the Ptw was signif icantly higher inthe IDgroup compared tothecontrol group atpost-EX and throughout therecovery period(p<0.05)(Fig.2C).

3.2.4.RMS/Mmax

The two-way ANOVA on the relative RMS/MmaxVL revealed signif icant effects of Group (F(1,18)=5.02,p<0.05),Time(F(4,72)=9.29,p<0.001),and Group×Time interaction(F(4,72)=6.04,p<0.001).The post hoc results showed asignif icant(p<0.001)decrementat post-EX in the ID group but unchanged valuesin thecontrol group(p=0.53).At post-EX 3-9,thesevaluesstarted to recover(p<0.001)but did not reach afull recovery even at post-EX 24-33.Regarding the between-group effects,the post hoc analysis showed that the RMS/MmaxVL values were signif icantly lower in the ID group compared to the control group at post-EX(p<0.001)and at post-EX 3-9(p<0.05)(Table 2).

On the VM muscle,signif icant main effects of Group(F(1,18)=6.92,p<0.05)and Time (F(4,72)=13.24,p<0.001)were observed but no signif icant Group×Time interaction(F(4,72)=1.56,p=0.19)wasreported.Regarding the time effect,the post hoc analysis revealed a signif icant(p<0.001)decrement of RMS/MmaxVM at post-EX in the control group.These values started to recover at post-EX 3-9(p<0.01),with acompleted recovery at post-EX 24-33.In the ID group,the post hoc analysis also revealed a signif icant(p<0.001)decrementatpost-EX.Atpost-EX 3-9,thesevalues started to recover(p<0.01)but did not reach a full recovery even at post-EX 24-33(p<0.05).The post hoc analysis also showed that the ID group presented lower valuesof RMS/MmaxVM compared to the control group at post-EX and during the recovery period(p<0.05)(Table 2).

Finally,for the RF muscle,the two-way ANOVA revealed signif icant main effectsof Group(F(1,18)=11.36,p<0.001),Time(F(4,72)=11.87,p<0.001),and Group×Time interaction(F(4,72)=3.66,p<0.01).Concerning thetimeeffect,the post hoc test showed that the RMS/MmaxRFdecreased signif icantly at post-EX(p<0.001)in thecontrol group.Thesevalues showed a full recovery(no signif icant difference with baseline values)at post-EX 3-9.Similarly,in the ID group,the RMS/MmaxRF decreased signif icantly at post-EX(p<0.001)and started to recover at post-EX 3-9 but the full recovery did not occur.The post hoc results also showed that the RMS/MmaxRF values were signif icantly lower in the ID group than in the control group(pre-EX and post-EX,p<0.05;post-EX 3-9 and post-EX 12-21,p<0.001;post-EX 24-33,p<0.01)(Table2).

4.Discussion

Theaim of our study wasto investigatetheability to sustain exhausting sub-maximal isometric contraction in individuals with ID compared to those with typical development and to explore the magnitude,the neuromuscular fatigue origin,and the subsequent recovery in these individuals.The results of the current study conf irmed our hypothesis by showing that individuals with ID were able to sustain the sub-maximal force level for alonger duration compared with controls.Therelative IMVC decline at exhaustion and the subsequent IMVC recovery prof ile were similar between groups,but their origin differed.The longer time to task failure in the ID group was associated with reduced peripheral fatigue and higher central fatigue compared to the control group.The central fatigue did not recover in the ID group whereas,in the control group,it recovered within the f irst 9 min.

Individuals with ID developed lower baseline values of IMVC,VAL,RMS/MmaxRF,and Ptw compared to the control group.Our resultsareconsistentwithpreviousf indings,14which suggestthat individualswith ID havealower ability to generate amaximal force,accounted for by peripheral and central factors.Nevertheless,our results showed that individuals with ID presented similar IMVCdecline to individuals with typical development after an isometric sub-maximal exhausting contraction.Thisresult isin disagreement with those of previousstudies.In fact,Zafeiridiset al.19reported lower forcedeclinecompared to controlsin theseindividualsafter an intermittent high-intensity exercise.In contrast,Borjiet al.17revealed greater forcedecline inindividualswith IDthancontrolsafter maximal repeated knee extensions and f lexions.This contradiction could be explained by differences in the fatiguing protocol(exercise intensity and duration).Borji et al.17explored the neuromuscular fatigue in these individuals after 5 sets of repeated knee extensions and f lexionsat 80%maximal repetition.Likewise,Zafeiridiset al.19implemented a fatiguing exercise consisting of maximal knee extensions and f lexions for both individuals with ID and those with typical development.Participantsin thisstudy19performed 4×30 s of maximal f lexion and extension cycles at angular velocity 120°/s separated by 60 s of rest.Conversely,in the presentstudy,thefatiguing exercisewasalow-intensity isometric contraction sustained until exhaustion and with individualized intensity(15%of each participant IMVC).Moreover,individualswith IDhad abetter performance,thatis,longer time to exhaustion,than controls.These results are consistent with previous studies showing that individuals characterized by low maximalforcecapacities,suchaswomen,childrenor theelderly,have abetter ability to sustain sub-maximal4,5or maximal force levels.6,28Yamadaetal.12alsoreported greater endurancecapacitiesin individualscharacterized by alow VAL,asin thecaseof the ID group.

Thelonger exerciseduration observed in the IDgroup could accountfor thepredominanceof central fatigueinthisgroup,as evidenced by the pronounced decrease of VAL and normalized EMGactivity after thefatiguingexerciseinthisgroup compared to individualswith typical development.Indeed,it iswell documented that sustained lower intensity contractions induced central fatigue rather than peripheral fatigue.7,9,29The greater central fatigueobserved inthe IDgroup compared tothecontrol onecouldberelatedtoabnormalitieswithintheircentralnervous system.Indeed,in these individuals reduction in number of neurons,dendritic abnormalities,and neurotransmitter system dysfunction have been reported,21,22,30which could impair the descending neural drive.31In addition,individuals with ID may suffer from other abnormalities within the spinal cord32,33that may impair motor units recruitment during muscle contraction.Beyond the greater magnitude of central fatigue,the ID group displayed aslow recovery from thiscentral fatiguecompared to individuals with typical development.Using the same exercise protocol,Zghal et al.34showed that recovery of central fatigue occurswithin 10 min in sedentary or trained adultswith typical development.Recently,ithasbeenconf irmed thatcentralfatigue recovers more quickly than the peripheral one after a fatiguing exercise in healthy adults.35Thus,the ID group displayed a distinctrecovery prof ileof central fatigue.Suchslow recovery of central fatigue has already been reported in the elderly36who developed also alow VAL.37

The ID group was mainly characterized by an attenuated peripheral fatiguewithafaster recovery compared tothecontrol group.Inthiscontext,Nordlund etal.10reported thatindividuals havingalow VALpresentlower extentof peripheral fatigueafter afatiguingexercisecompared toindividualswithhigh VAL.Our resultsareinlinewiththoseof Rateletal.28showingthatchildren produce lower force,present a longer time to task failure,develop more central fatigue,and recover from peripheral fatiguefaster than adults.Becauseadultswith ID demonstrated a similar VAL with children without ID,13they seem to present similar neuromuscular fatigue prof ile.Moreover,we cannot excludethatthelowerperipheral fatigueintheIDgroup could be attributed to specif ic muscle properties.Because it has been reviewed that the increased accumulation of by-products(lactate,H+)of anaerobic metabolism impairs the excitationcontraction coupling and cross-bridges formation,20the lower lactate accumulation observed in individuals with ID could explain the low peripheral fatigue magnitude.19,38It has been shown that individuals with ID present lower peak and mean power levelsand that they accumulatelessblood lactateduring the Wingatetest.38Theseauthorsassociated theselower performance lactate concentrations to a lower extent of fast-twitch musclesf ibersbecausetheWingatetestperformancedependson the predominance of these muscle f ibers.39Furthermore,Zafeiridis et al.19found lower blood lactate concentration in theseindividualscompared to controlsafter 4×30 sof maximal f lexion and extensioncyclesatangular velocity 120°/sseparated by 60 sof rest.Therefore,itseemstobereasonabletoexpectthat thiscould beduetothelimited extentof typefast-twitchmuscle f ibersreported in individualswith ID40whereas further studies should beconducted to explorethissuggestion.

This study has some limitations.Although the twitch interpolation is an eff icient technique to explore the implication of central and peripheral factors in neuromuscular fatigue,it would be interesting to explore the cortical activation in individuals with ID using the transcranial magnetic stimulation in future investigations.It will be interesting to know whether spinal or spinal accompanied by supraspinal nervous system anomalies are involved in this accentuated and persistent central fatigue reported in individuals with ID compared to controls.In the present study,we only evaluate the magnitude and theorigin of neuromuscular fatigue in individuals with ID.It would be very interesting to apply,in a future study,the superimposed and the potentiated twitch at intervals during the fatiguing exercise to assess the contribution of central and peripheral fatigueto force decline aswell astheneuromuscular fatigue processing kinetic in these individuals.

5.Conclusion

Our f indings showed that individuals with ID developed lower maximal forcebut sustained thesub-maximal contraction for a longer duration than individuals without ID.Although individuals with ID presented similar maximal voluntary force decrement at exhaustion and similar subsequent recovery kinetic with individuals without ID,the origin of this neuromuscular fatigue isradically different.In fact,individualswith ID developed mainly central fatigue but a limited peripheral one.Moreover,individuals with ID presented a persistent central fatigue without recovery but a faster recovery from peripheral fatigue than individuals with typical development.Thedistinctfatigueand recovery pattern of the ID group should be taken into account when designing training programs or occupational activities for individuals suffering from ID.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all participants for their understanding and availability.In addition,great thanks go to all collaboratorsand volunteersof the National Union of Aid to Mental Insuff iciency for their contribution in this study.

Authors'contributions

RB conceived of the study,arranged participants'recruitment,performed dataacquisition,statistical analysis,datainterpretation,and drafted the manuscript;FZ contributed to study conception,data acquisition and interpretation,and helped draft the manuscript;NZ contributed to data interpretation and revising the manuscript;VM contributed to statistical analysis and critically revised the manuscript;SScontributed to statistical analysis and helped draft the manuscript;HR contributed to study design and coordination,data interpretation,and critically revising of the manuscript.All authors have read and approved thef inal version of themanuscript,and agreewith the order of presentation of the authors.

Competinginterests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Journal of Sport and Health Science2019年3期

Journal of Sport and Health Science2019年3期

- Journal of Sport and Health Science的其它文章

- Corrigendum Corrigendum to“Denervated muscleextract promotesrecovery of muscle atrophy through activation of satellite cells.An experimental study”[JSport Health Sci8(2019)23-31]

- Original article Group dynamicsmotivation to increaseexerciseintensity with a virtual partner

- Original article Adolescents'personal beliefsabout suff icient physical activity aremore closely related to sleep and psychological functioning than self-reported physical activity:A prospectivestudy

- Original article Parents'participation in physical activity predicts maintenance of some,but not all,types of physical activity in offspring during early adolescence:A prospective longitudinal study

- Original article Determination of functional f itness age in women aged 50 and older

- Original article Association of objectively measured physical activity and sedentary time with health-related quality of lifein women with f ibromyalgia:Theal-′Andalusproject