Opinion New scientif ic basisfor the2018 U.S.Physical Activity Guidelines

Lortta DiPitro *Davi M.Buhnr ,Davi X.Marquz ,Russll R.Pat,Lina S.Psatllo ,Mliia C.Whitt-Glovr

a Department of Exerciseand Nutrition Sciences,Milken Institute School of Public Health,The George Washington University,Washington,DC 20052,USA

b Department of Kinesiology and Community Health,University of Illinoisat Urbana-Champaign,Champaign,IL 61801,USA

c Department of Kinesiology and Nutrition,University of Illinoisat Chicago,Chicago,IL 60612,USA

d Department of Exercise Science,Arnold School of Public Health,University of South Carolina,Columbia,SC 29208,USA

eDepartment of Kinesiology,Collegeof Agriculture,Health and Natural Resources,Universityof Connecticut,Storrs,CT 06269,USA

fGramercy Research Group and Winston-Salem State University,Winston-Salem,NC 27110,USA

The U.S.Department of Health and Human Services convened the 2018 Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee (PAGAC)and charged it with reviewing and summarizing the current scientif ic evidence linking physical activity to human health and function.The 2018 PAGAC Scientif ic Report1serves as the basis for the Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans,2nd edition.2The 2018 Scientif ic Report extends the f indings of the 2008 Scientif ic Report3by examining a broader range of health outcomes and special populations that benef it from increased physical activity.In addition,the 2018 Scientif ic Report more closely examined the specif ic types,volumes,and intensitiesof physical activity that are associated with thosebenef itsand now describesnovel strategies for physical activity promotion at the population level.A full overview of the process and methods for compiling the scientif ic evidence,as well as the important new f indings from the 2018 PAGAC Scientif ic Report,have recently been published.4In this Opinion Piece,we summarize the important topics that were not addressed in 2008(Table 1).The full 2018 Scientif ic Report is available at https://health.gov/paguidelines/second-edition/report.aspx.

1.Physical activity in early childhood

Thef irst edition of the Physical Activity Guidelinesfor Americans,released in 2008,included physical activity recommendations for children and youth.5Those 2008 Guidelines applied only to school-age children(6-17 years),because at that time,the body of knowledge on the health effects of physical activity in children<6 years of age was too limited to support any conclusions.The absence of physical activity recommendations for early childhood has changed,owing to important developments over the decade between the release of the f irst and second editions of the Physical Activity Guidelines.Most important,the evidence linking physical activity to health during early childhood has expanded markedly.Also,during that period,physical activity recommendations for young children were produced by the Instituteof Medicineinthe United Statesand by public health authoritiesin several other countries.6,7

The more recent research on the health effects of physical activity in young children focuses largely on children of preschool age(3-5 years).Further,this research targets indicators of 2 critical pediatric health outcomes—weight status/adiposity and bone health.The 2018 PAGAC concluded that,for both weight status/adiposity and bone health,there was strong evidence linking higher levels of physical activity to better outcomes in 3-to 5-year-old children.For weight status/adiposity,this conclusion was based on the consideration of 15 studies,all of which used prospective,observational study designs.Twelve of those studies reported that higher levels of physical activity were associated with lower rates of gain in weight and/or fat mass in early childhood.For bone health,3 studies using either experimental or prospective,observational designs were available,and all 3 reported the positive effectsof higher levelsof physical activity on bonestrength in 3-to 5-year-olds.

Although substantial,the evidence linking physical activity to health in early childhood has some limitations.For instance,existing data do not allow a clear assessment of dose-response relationships,and,therefore,it is not currently possible to identify a specif ic amount of physical activity that is needed to produce these observed health benef its.Future research should specif ically address this limitation.In addition,research is needed to determine whether or not physical activity inf luences other important health outcomes of early childhood,such as indicators of cardiometabolic health and brain health.

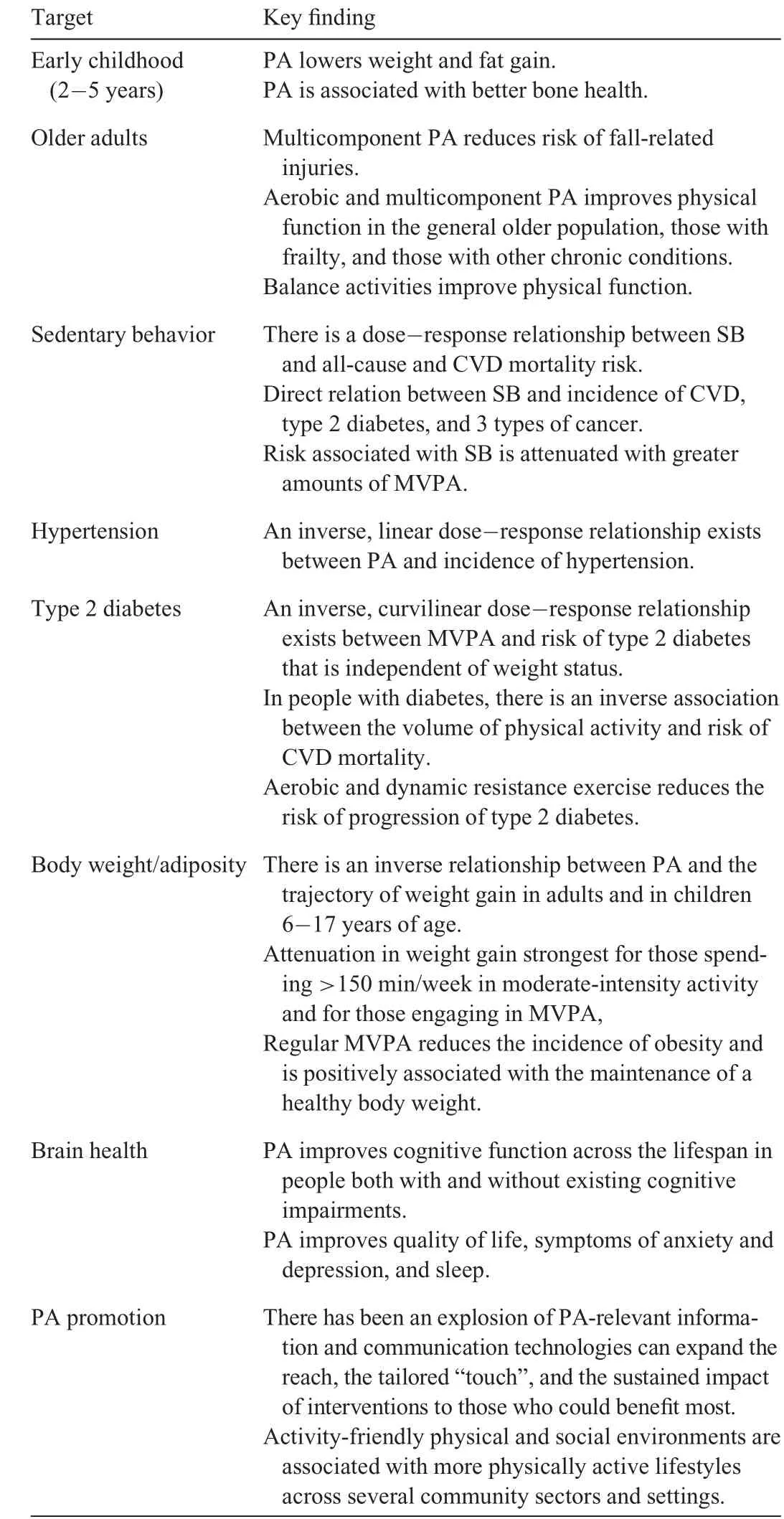

Table1Summary of key new f indingsfrom the2018 PAGACScientif ic Report.

2.Aging and chronic conditions

Evidence from randomized trials linking regular physical activity to major health benef itsin aging hasgrown rapidly in the past 10 years—and the f indings in older adults are even more impressive than they are at younger ages.In the 2008 PAGAC Scientif ic Report,there was strong evidence that exercise programs targeted toward fall prevention substantially decreased the risk of falls,and thatbalancetraining wasan effectivecomponent of such programs.Now thereisstrong evidencethat multicomponent programscan reducethe risk of injuriesresulting from falls,with meta-analysesreporting risk reductionsof≥40%.

There is now strong evidence that aerobic activity and muscle-strengthening activities improve physical function in older adults.Moderate evidence also indicates that balance activities improve physical function in this age group,thereby supporting recommendations for balance training among all older adults(rather than for only those at increased fall risk).Moreover,any concerns that the benef its of physical activity to physical function may decrease with older age and be mitigated by frail health are not supported by current evidence.Indeed,although limited evidence suggests that age does not inf luence the effect of physical activity on physical function,there was strong evidencethateven adultswithexistingfrailty canbenef it from adding physical activity to their lifestyle.Infact,thereisnow strong or moderateevidencethat physical activity provideshealth benef itsto people with a widevariety of chronic conditions,including type 2 diabetes,stroke,multiple sclerosis,osteoarthritis,Parkinson disease,and 3 typesof cancer.

The 2018 Physical Activity Guidelines continue to aff irm the importance of regular aerobic activities,such as walking for older people.However,they also emphasize multicomponent physical activity and recommend including regular muscle strengthening and balance activities to the weekly physical activity plan.Moreover,data from randomized trials clearly demonstrate that the health benef its of this type of activity in older adults occur after relatively short periods of training(i.e.,3-12 months depending on the health outcome of interest),suggesting that multicomponent physical activity may be our most potent countermeasureagainst aging-associated functional decline.Unfortunately,only about 20%of U.S.adults meet the 2008 federal guidelines for aerobic and musclestrengthening activity.Therefore,theclinical and public health benef its of increasing levels of multicomponent activity in older adults are substantial.The f irst sentence of the Executive Summary of the 2018 PAGACScientif ic Report statesthat the evidence“abundantly demonstrates that physical activity is a‘best buy'for public health”.Nowhere is the evidence for this statement more compelling than in older adults.

3.Sedentary behavior

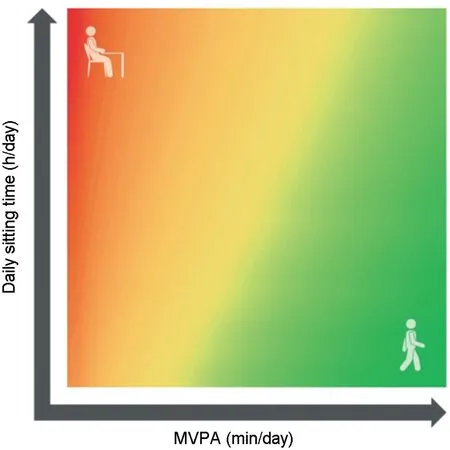

The 2018 PAGAC Scientif ic Report identif ies a direct relationship between sedentary behavior and all-cause and cardiovascular disease(CVD)mortality,incidence of CVD and type 2 diabetes,as well as the incidence of endometrial,colon,and lung cancers.Mortality risk increasesin a dose-response manner with increasing amounts of sitting time;however,this sedentary-related mortality risk is attenuated with greater volumes of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity(MVPA).8In fact,for individuals reporting the greatest volume of MVPA(about 35-38 metabolic equivalent of task hours(MET-h)per week),the excess mortality risk within different categories of sitting seems to be negligible,thus indicting a robust interaction between physical activity and sedentary time.For instance,sedentary time,as well as light physical activity and MVPA interact within a f inite,24-hour day.The 2018 PAGAC developed a heat map illustrating the interplay between variouscombinations of sitting time and MVPA and their joint effects on all-cause mortality(Fig.1).The heat map was derived from regression techniques based on harmonized data from a meta-analysisby Ekelund et al.8An assumption wasmadethat,for any given level of MVPA,the time spent sitting and the time spent in light intensity physical activity are reciprocal.Thus,greater amounts of sitting time over the course of a day will displace light-intensity physical activity and vice versa.As indicated by theheat map:(1)atlow levelsof MVPA,replacing sitting timewith light-intensity physical activity reducestherisk of premature mortality;(2)MVPA is necessary to achieve the greatest risk reduction;(3)for an equivalent reduction in risk,increasing MVPA requires appreciably less time per day than increasing light-intensity physical activity;and(4)at thehighest levels of MVPA(about 35-38 MET-h/week),the time spent sitting hasanegligibleeffect on mortality risk.

Fig.1.Relationship among moderate-to-vigorous physical activity(MVPA),sitting time,and risk of all-cause mortality.The red zone illustrates greater mortality risk with higher amountsof sitting time combined with low levelsof MVPA(top left corner).The green zone illustrates how higher amounts of MVPA can mitigate the risk of even moderate-to-high levels of sitting time(top right area).

4.Physical activity and hypertension

The 2018 PAGAC Scientif ic Report cites strong evidence for a linear,inverse dose-response relationship between leisuretimephysical activity of any intensity and incident hypertension,with no upper threshold of benef it among adults with normal blood pressure.For each 10 MET-h/week increment in leisure time physical activity,the risk of developing hypertension decreases by 6%.9Among people with hypertension,increasing the systolic blood pressure will increase the risk of CVD mortality;however,thisexcess CVD mortality isblunted among thosewho are more physically active.

Improvementsin blood pressurewith regular physical activity depend on the initial blood pressure levelsof an individual,with the greatest improvements observed in those with the greatest impairments.Adults with hypertension may experience an improvement of about 4%-6%of their resting blood pressure level(5-8 mm Hg),followed by those with prehypertension(2%-4%of resting level;2-4 mm Hg),and those with normal blood pressure(1%-2%of resting level;1-2 mm Hg).These improvements occur immediately after an exercise session and seem to be independent of exercise modality.This latter f inding is a departure from the current exercise and hypertension guidelines that recommend aerobic over dynamic resistance exercise for theprevention and treatment of hypertension.10

5.Physical activity and type 2 diabetes

The2018 PAGACalso found strong evidence of an inverse curvilinear dose-response relationship between MVPA and the development of type 2 diabetes that was independent of weight status.Indeed,150-300 min/week of moderate-intensity activity decreases the risk of diabetes by 25%-35%.There is also strong evidence of an inverse association between the volume of physical activity and risk of CVD mortality(a 30%-40%decrease in risk),which is the most common cause of death among adults with type 2 diabetes and an indicator of disease progression.The PAGAC examined 4 indicators of type 2 diabetes risk progression that included hemoglobin A1C,blood pressure,body mass index(BMI),and blood lipid concentrations.The new f indings indicate that aerobic and dynamic resistance exercise(performed alone or combined)reduces the risk of progression of type 2 diabetes,with the strength of the relationship varying by individual risk factor.Again,those with the greatest levels of impairment in hemoglobin A1C,blood pressure,or lipid concentrationsexperience the greatest improvements in cardiometabolic health and the magnitude of these health effects is greater the longer one participates in exercise.Regular physical activity also improves insulin sensitivity,with transient benef its occurring immediately after exercise.

6.Physical activity and weight/adiposity

The 2008 PAGAC Scientif ic Report concluded that physical activity was associated with modest weight loss,prevention of weight regain,and decreases in total and regional adiposity.The focus of the 2018 PAGAC Scientif ic Report was on the primary prevention of excessive weight gain.The 2018 Scientif ic Report describes a strong inverse relationship between physical activity and the trajectory of weight gain in adults,with the attenuation in weight gain strongest for those spending morethan 150 min/week in moderate-intensity activity and for those engaging in MVPA.Regular MVPA also reducesthe incidence of obesity(BMI≥30 kg/m2)and ispositively associated with the maintenance of a healthy body weight(BMI:18.5-24.9 kg/m2).

Among children 6-17 years of age,the 2018 Scientif ic Report cites strong evidence from prospective,observational studiesthat higher levelsof physical activity areassociated with smaller increases in body weight and adiposity.These benef its areobserved in both boysand girls,aswell asin preschool children.Although the data are limited,there is some evidence that sedentary behavior is associated with higher weight status or adiposity in children and adolescents;however,the evidence is stronger for television viewing and screen time than for total device-based sedentary time.

7.Brain health and cognition

The topic of Brain Health was added to the 2018 PAGAC Scientif ic Report owing to theexpanding body of evidenceciting thebenef itsof regular physical activity to cognition,affect,and sleep.The 2018 Scientif ic Report now indicates that physical activity positively inf luences cognitive function across the lifespan in people both with and without existing cognitive impairments and that these benef its are consistent across a variety of methodsfor assessing cognition.The2018 Scientif ic Report also describes for the f irst time the positive effects of physical activity on biomarkers of brain health(e.g.,brain volume)that were obtained from neuroimaging techniques and describesevidenceon theacuteeffectsof singleexercisebouts on improvementsin cognitivefunction.

The evidence linking physical activity to mental health is now described in greater depth than in the 2008 Scientif ic Report.For example,the 2018 Scientif ic Report highlights the benef its of physical activity to validated indicators of quality of life(QoL)(rather than a limited def inition of“well-being”).Indeed,the2018 Scientif ic Report describestheeffectsof physical activity on physical and mental domains of health-related QoL with data from clinical trials that were conducted across thelifespan and in populationsthat often show signif icant losses in QoL(e.g.,people with schizophrenia).The 2018 Scientif ic Report also providessound evidencethat regular physical activity isan effectivetreatment for decreasing symptomsof anxiety and depression acrossmultiple age groupsand that both regular and single bouts of physical activity have positive effects on several different sleep outcomes,including sleep apnea.

8.Physical activity promotion

Strategies to promote physical activity and reduce sedentary behavior were not included in the 2008 Scientif ic Report or the 2008 Guidelines.Given the surplus of literature describing the effectiveness of different interventions for promoting physical activity at the individual level,it wassurprising to discover that there were no def niitive answers about what works best to promote and sustain an active lifestyle at the population level.The 2018 Scientif ic Report describes effective strategies targeted toward multiple levels within the social ecological framework.Indeed,many of the successful approaches described have been directed toward individuals via specif ci channels,such as telephone-based advice and support,text messaging,smartphone apps,and other forms of electronic communication.The explosion of physical activity-relevant information and novel communication technologies provides an unprecedented opportunity to expand the reach,the tailored“touch”,and the sustained impact of interventions to those who could benef ti most.In addition,a largeamountof evidenceindicatesthat activity-friendly physical and social environments are associated with more physically active lifestyles across age groups,settings(school,workplace),and different formsof activity(recreation,activetransport).

The 2018 Scientif ic Report also highlights what we still do not know about promoting physical activity.The primary knowledge gap relates to the“scaling up”of interventions that work well with motivated volunteers under standardized(i.e.,ideal)conditions,but then break down under real-life conditions at the community or population level.In fact,translating f indings from the laboratory to the population level remains a signif icant challenge for public health researchers and practitioners alike,and this is even more problematic when working with under-represented and/or low-resourced communities.

9.Conclusion

Findingsfrom the 2018 Scientif ic Report continueto underscore the public health impact of increasing population levels of regular physical activity and provide a f irm foundation for the new federal physical activity guidelines for Americans.Regular physical activity can prevent themost common causes of early mortality,as well as the most prevalent chronic conditions and most expensive medical conditions in the United States.4Thus,even small increasesin regular physical activity,especially if made by the least physically active individuals,would appreciably decrease the burden and cost of lifestylerelated disease in the United States.

References

1.Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee.2018 Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee Scientif ic Report.Washington,DC:U.S.Department of Health and Human Services;2018.

2.U.S.Department of Health and Human Services.2018 Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans.2nd ed.Washington,DC:U.S.Department of Health and Human Services;2018.

3.Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee.2008 Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee Scientif ic Report.Washington,DC:U.S.Department of Health and Human Services;2008.

4.Powell KE,King AC,Buchner DM,Campbell WW,DiPietro L,Erickson KI,et al.The scientif ic foundation of the physical activity guidelines for Americans.JPhys Act Health 2019;17:1-11.

5.U.S.Department of Health and Human Services.2008 Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans.Washington,DC:U.S.Department of Health and Human Services;2008.

6.McGuire S.Institute of Medicine(IOM)Early childhood obesity prevention policies.Washington,DC:The National Academies Press;2011.Adv Nutr 2012;3:56-7.

7.Pate RR,O'Neill JR.Physical activity guidelines for young children:an emerging consensus.Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2012;166:1095-6.

8.Ekelund U,Steene-Johannessen J,Brown WJ,Fagerland MW,Owen N,Powell KE,et al.Does physical activity attenuate,or even eliminate,the detrimental association of sitting time with mortality?A harmonised meta-analysisof datafrom morethan 1 million men and women.The Lancet 2016;388:1302-10.

9.Liu X,Zhang D,Liu Y,Sun X,Han C,Wang B,etal.Dose-responseassociation between physical activity and incident hypertension:asystematic review and meta-analysisof cohortstudies.Hypertension 2017;69:813-20.

10.Pescatello LS.Exercise measures up to medication as antihypertensive therapy:its value has long been underestimated.Br J Sports Med 2018.doi:10.1136/bjsports-2018-100359.

Journal of Sport and Health Science2019年3期

Journal of Sport and Health Science2019年3期

- Journal of Sport and Health Science的其它文章

- Corrigendum Corrigendum to“Denervated muscleextract promotesrecovery of muscle atrophy through activation of satellite cells.An experimental study”[JSport Health Sci8(2019)23-31]

- Original article Group dynamicsmotivation to increaseexerciseintensity with a virtual partner

- Original article Adolescents'personal beliefsabout suff icient physical activity aremore closely related to sleep and psychological functioning than self-reported physical activity:A prospectivestudy

- Original article Parents'participation in physical activity predicts maintenance of some,but not all,types of physical activity in offspring during early adolescence:A prospective longitudinal study

- Original article Determination of functional f itness age in women aged 50 and older

- Original article Association of objectively measured physical activity and sedentary time with health-related quality of lifein women with f ibromyalgia:Theal-′Andalusproject