Microbial metabolites in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

Da Zhou, Jian-Gao Fan

Abstra c t The p revalence of non-alcoholic fatty liver d isease (NAFLD) is rising exponen tially w orldw ide. The spectrum of NAFLD includes non-alcoholic fatty liver, non-alcoholic steatohepatitis, liver cirrhosis, and even hepatocellu lar carcinom a. Evidence show s that m icrobial m etabolites p lay p ivotal roles in the onset and p rogression of NAFLD. In this review, w e d iscuss how m icrobederived m etabolites, such as short-chain fatty acids, endogenous ethanol, bile acids and so forth, contribu te to the pathogenesis of NAFLD.

Key words: M icrobial metabolites; Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis; Short-chain fatty acids

INTRODUCTION

Non-alcoholic fatty liver d isease (NAFLD) is a ch ronic m etabolic d isorder that is strong ly associated w ith obesity and m etabolic synd rom e. NAFLD has becom e the m ost comm on ch ronic liver d isease w orldw ide[1,2], causing a substantial global health bu rden. A lthough the exact pathogenesis of NAFLD is uncertain, in ad d ition to the w ell-know n “tw o-hit” theory or the m u ltip le-parallel-hits hypothesis[3,4], the dysbiosis of the gu t m icrobiota also p rom otes the developm ent of NAFLD by m ed iating the p rocesses of energy m etabolism, insu lin resistance, imm unity, and in flamm ation[5-7].

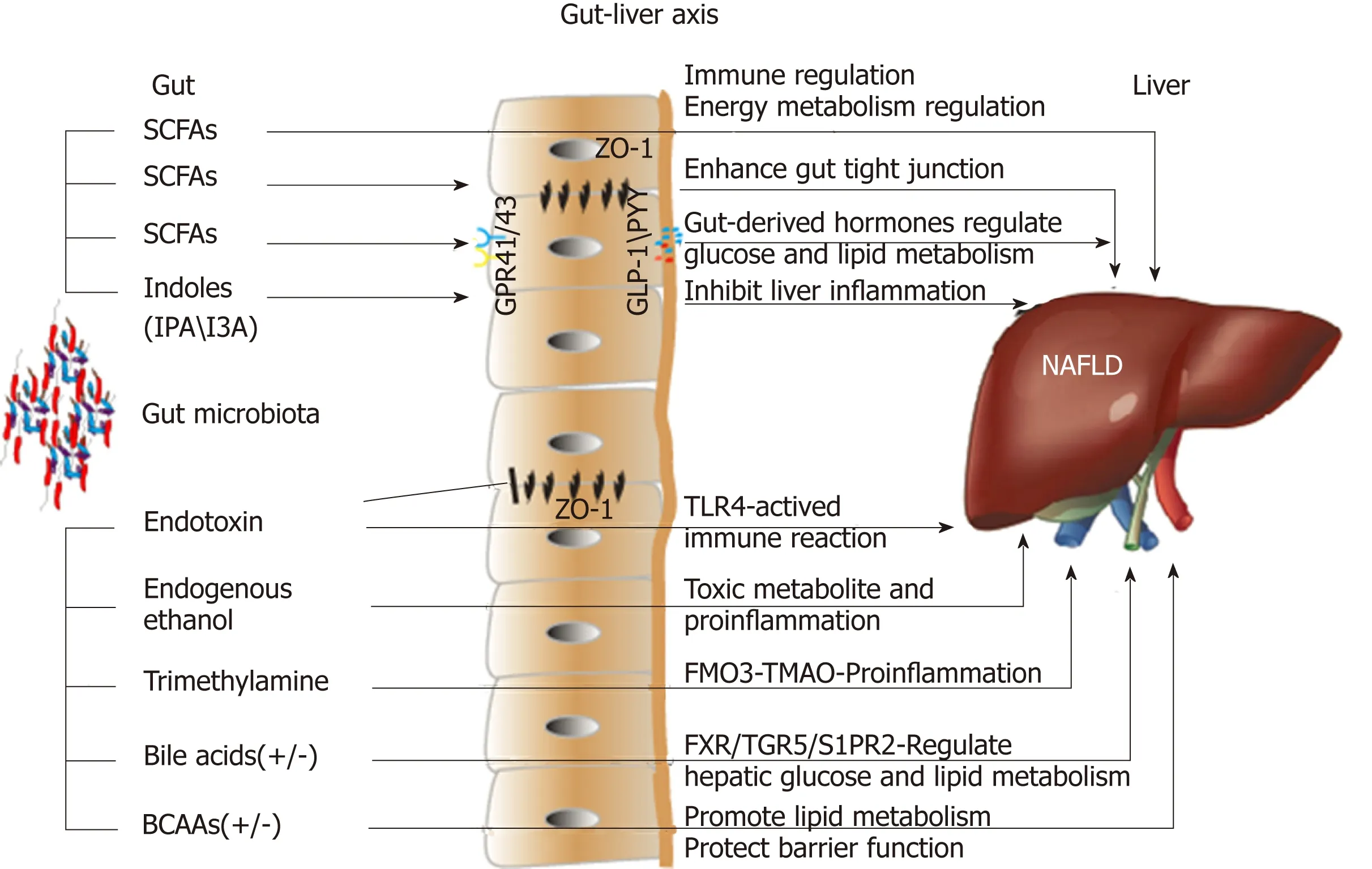

The gu t flora in the intestinal tract exhibits high d iversity and d istinct d ifferences,and the total num ber of bacterial cells can reach 1014[8]. The intestinal bacteria m ain ly belong to the fo llow ing p h y la: Firm icu tes, Bacteroid etes, A ctinobacteria,Proteobacteria, Verru com icrobia, and Fusobacteria; together, Firm icu tes and Bacteroidetes account for up to 90% of all bacterial cells in the hum an intestine. The gu t m icrobiota is deem ed a special "organ" in hum an beings; bacterial genes are ap p roxim ately 100-fold m ore abundan t than hum an genes, and they encode m ore functional genes[8]. A large p roportion of bacterial genes and their biological functions are specific, and the m etabolic potential related to the capacity for the conversion and degradation o f host-derived substances is strong. Therefore, the gu t m icrobiota exhibits a p rofound capacity to synthesize or p roduce m any m etabolites. Recently,increasing evidence has show n that these m etabo lites p lay p ivotal ro les in the in teractions betw een the gu t m icrobiota and the host in various w ays, and the gu tliver axis is the m ain link betw een the gu t and the liver (Figu re 1). Natu rally, an im balance in the intestinal m icrobiom e and the related m etabolites contribu tes to the onset and p rogression of NAFLD[9,10]. The accu rate pathological d iagnosis of NAFLD relies on a liver biopsy; how ever, w ith fu rther investigation, the gu t m icrobiota and its m etabo lites m ay serve as p oten tial biom arkers for NAFLD and non-alcoho lic steatohepatitis (NASH). A clinical study dem onstrated that certain gu t m icrobiom ederived m etabolites shared gene-effects w ith hepatic steatosis and liver fibrosis[11,12]. In ad d ition, another study used targeted m etagenom ics and m etabolom ics analysis to dem onstrate that a decrease in Oscillospira accom panied by up regu lation o f 2-butanone and an increase in Rum inococcus and Dorea w ere signatu res of non-alcoholic fatty liver (NAFL) onset and NAFL-NASH p rogression[13]. How ever, ad d itional validations w ith clinical sam p les are needed.

Recently, several original investigations show ed that the severity of NAFLD is associated w ith changes in the levels of certain m etabolites in the serum; although not all su ch m etabo lites are syn thesized or p rodu ced by gu t bacteria[12,14-16], a better understand ing of the role of these m etabolites in the developm ent of NAFLD w ill be valuable for the d iscovery of new non-invasive d iagnostic and treatm ent op tions for NAFLD.

SHORT-CHAIN FATTY ACIDS (SCFAS)

The m ost im portant bacterial m etabolites are SCFAs, w hich con tain few er than six carbon atom s and have becom e an increasingly stud ied gu t m etabolite due to their m u ltip le biological functions in the liver[17]. The ferm entation of d ietary fibers by gu t bacteria, includ ing Roseburia, Rum inococcus, Salmonella, Blau tia, Eubacterium,Anaerostipes, Coprococcus, Faecalibacterium, M arvinbryantia, and M egasphaera, is the m ain sou rce of SCFAs. The m ost abundant SCFAs p resent in the colon lum en are acetate, p rop ionate, and bu tyrate[18]. SCFAs not on ly p rovide energy for the intestinal ep ithelium, bu t they also have m any bioactive ro les, such as the regu lation o f imm unity, lipom etabo lism, and g lycom etabo lism, and the m ain tenance of gu t m icrobiota hom eostasis. SCFAs are involved in the pathogenesis of NAFLD after their absorp tion and delivery to the liver via the portal vein. A clinical study show ed that p rop iona te su p p lem en ta tion sign ifican tly red u ced w eigh t gain an d in trahepatocellu lar lip id con ten t, p reven ted deterioration in the case o f insu lin sensitivity, and significantly stim u lated the release of pep tide-YY and glucagon-like pep tide-1 (GLP-1) from hum an colonic cells; these horm ones are closely related to energy m etabolism[19]. Another clinical study show ed that the total am ount of SCFAs was higher in obese subjects com pared w ith lean subjects and, m oreover, the ratio of the phy la Firm icutes to Bacteroidetes was altered in favor of Bacteroidetes in obese hum ans[20]. Basic stud ies have show n that bu tyrate-p roducing p robiotics corrected high-fat d iet (HFD)-induced en terohepatic imm unologic d issonance and attenuated steatohepatitis in m ice, w hich is m ed iated in part through SCFAs[21-23]. A clinical study show ed that a select group of SCFAs-p roducing bacterial strains p layed p ivotal roles in regu lating g lucose and lip id m etabo lism, in part th rough increased GLP-1p roduction; therefore, the targeted restoration of these SCFA p roducers m ay p resent a novel ecological app roach for m anaging m etabolic synd rom e and NAFLD[24].

Figure 1 Effects of microbial metabolites on non-alcoholic fatty liver disease via the gut-liver axis. SCFAs: Short-chain fatty acids; I3A: Indole-3-acetic acid;IPA: Indole propionic acid; GPR41/43: G-protein-coupled receptors 41/43; ZO-1: Zonula occludens 1; GLP-1: Glucagon-like peptide-1; PYY: Peptide YY; TLR4: Tolllike receptor 4; FMO3: Flavin-containing monooxygenase 3; TMAO: Trimethylamine-N-oxide; FXR: Farnesoid X receptor; TGR5: Takeda G-protein-coupled receptor 5; S1PR2: Sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor 2; BCAAs: Branched-chain amino acids.

Increasing stud ies have revealed that SCFAs exert their biological functions m ain ly via activating the G-p rotein-coup led recep tor (GPR) 41/43 or through the inhibition of histone deacety lase (HDAC). Anim al experim en ts show ed that GPR41 and GPR43 w ere involved in lip id and imm une regu lation, and GPR41/43 deficiency p rotected against HFD-indu ced obesity, insu lin resistance, and d yslip id em ia, in part via increased energy expend itu re and the p rom otion of gu t-derived horm one GLP-1[25-27].In ad d ition, the activation o f GPR41/43 has been suggested to participate in the pathogenesis o f NAFLD. A s m en tioned above, excep t for the activation of GPRs,SCFAs can inhibit HDAC d irectly and regu late the transcrip tional activation of genes;am ong the SCFAs, bu tyrate is the m ost pow erfu l HDAC inhibitor[28]. Previous anim al stud ies show ed that sod ium bu tyrate supp lem entation cou ld attenuate HFD-induced NASH, and the underlying m echanism s w ere associated w ith restoring the dysbiosis of gu t m icrobiota and im p roving the gastrointestinal barrier, thereby inhibiting the delivery of gu t-derived endotoxin into the liver[29]. Recen tly, an investigation found that the exp ression of hepatic GLP-1 recep tor was significan tly dow n-regu lated in patients w ith NAFLD, and supp lem entation w ith bu tyrate enhanced hepatic GLP-1R exp ression in an NASH m ouse m od el by inhibiting h istone deacety lase-2 and activating AM P-activated p rotein kinase (AM PK). These find ings ind icated that bu tyrate cou ld be a GLP-1 sensitizer and cou ld p reven t the p rogression of NAFL to NASH via p rom oting the exp ression of hepatic GLP-1R[30].

In general, SCFAs are though t to be beneficial p rebiotics; how ever, a recent study dem onstrated that the solub le fiber inu lin, w hen ferm en ted by gu t bacteria in to SCFA s, cou ld ind u ce icteric hep atocellu lar carcinom a (HCC)[31], w hich was an astound ing find ing. How ever, SCFA-induced HCC was show n to be cond itional and m icrobiota-dependent, and this cond ition was observed in dysbiotic m ice; m eanw hile,the inhibition of ferm entation reduced intestinal SCFAs and p revented HCC. Thus,the enrichm ent of ferm entable fiber shou ld be p rom oted w ith cau tion, and the intake of d iverse types of d ietary fiber shou ld be em phasized to estab lish and m aintain healthy gu t m icrobiota. This top ic still requires fu rther investigation for the design,p rodu ction, and sup p ly o f rational food ad d itives to im p rove hum an health.Accord ing to various stud ies, it is very d ifficu lt to d raw accu rate conclusions abou t the roles of gu t m icrobiota and SCFAs in NAFLD because con found ing factors are extensive and cannot be ignored[32].

ENDOGENOUS ETHANOL AND ENDOTOXINS

It is w ell know n that ethanol is a substance that can contribu te to hepatic steatosis and in flamm ation and increase the risk of liver fibrosis and HCC[33]. Endogenous ethanol p rodu ced by bacterial ferm en tation (m ain ly by Rum inococcus) stim u lates oxidative stress and aggravates liver in flamm ation in NAFLD, w hich was con firm ed in anim al experim en ts[34]. Zhu et al[35]show ed that child ren and ad o lescen ts w ith NASH harbored m ore ethanol-p roducing bacteria in the gu t and exhibited higher serum levels of ethanol; m oreover, the exp ression of genes involved in alcohol m etabolism was enhan ced. Another clinical stud y show ed that ch ild ren w ith NAFLD had significantly higher serum levels of ethanol, w hich w ere associated w ith a greater abund an ce o f Gammaproteobacteria and Prevotella[36]. H ow ever, another stud y dem onstrated that the increased blood ethanol levels in patients w ith NAFLD m ight resu lt from insu lin-dependent im pairm ents of ethanol dehyd rogenase activity in the liver rather than an increase in endogenous ethanol syn thesis[37]. A lthough these stud ies d id not all p rodu ce consisten t resu lts, endogenous ethanol m igh t p lay a p ivotal ro le in the pathogenesis o f NASH. Fu tu re investigations are requ ired to determ ine the exact in fluence of endogenous ethanol on NAFLD and NASH.

System ic low in flamm atory state is related to the insu lin resistance (IR) w hich con tribu tes to the onset of NAFLD. Gram-negative bacteria-derived endotoxins such as lipop o lysaccharide (LPS) w ere p roved to stim u late and agg ravate hepatic necroin flamm ation. The increased in testinal perm eability and d ysbiosis o f gu t m icrobiota p rom ote the translocation of m icrobial p roducts from intestinal lum en to the liver via the portal vein[38]. Toll-like recep tors (TLRs), includ ing TLR4, w ere involved in the LPS-induced liver dam age, and LPS cou ld activate TLR4-m yeloid d ifferen tiation p rim ary-response gene 88 (M yd88) signaling pathw ay, causing IR,hepatic steatosis, liver in flamm ation, and fibrosis[39,40]. In ad d ition, Kup ffer cells positive for cluster of d ifferentiation 14 (CD 14) cou ld enhance LPS-TLR4 response in the liver[41].

BRANCHED-CHAIN AM INO ACIDS (BCAAS)

BCAAs are p roduced by p roteolytic ferm entation in the colon. Species im p licated in p roteolytic ferm entation include Clostridium, Fusobacterium, Bacteroides, Actinomyces,

Propionibacterium, and Peptostreptococci[42]. Patients w ith NAFLD have dysregu lation of BCAA m etabolism, the BCAAs includ ing leucine, valine, and isoleucine w ere higher both in the blood and u rine sam p les from NAFLD patients[16], the circu lating BCAAs w ere negatively correlated w ith hepatic insu lin sensitivity, and the baseline valine level was identified to be p red ictive of liver fat accum u lation[43]. M eanw hile, BCAAs cou ld reflect hepatic steatosis independently of rou tine m etabolic risk factors, and the m etabolic aberrations of BCAAs m ay p recede the developm ent of NAFLD to a certain extent[44]. The increased BCAA levels (valine, leucine, and isoleucine) and dow nstream BCAA m etabolites, such as branched-chain keto acids and short-chain acy lcarnitines,w ere associated w ith a greater body m ass index (BM I)[45]. Fu rther anim al experim ents show ed that BCAA supp lem en tation reduced HFD-induced overw eigh t, bu t caused obv ious liver dam age in HFD m ice, w h ich was associated w ith the abnorm al lipolysis[46]. Oppositely, several stud ies ind icated that BCAA in terven tion cou ld alleviate NASH in anim al m odels via inhibiting triglyceride deposition in hepatocytes and reducing oxidative and endop lasm ic reticu lum stress[47-50]. BCAAs w ere found to have the ability to im p rove imm une function, decrease suscep tibility to pathogens,p rom ote the grow th of intestinal beneficial bacteria, and enhance the intestinal barrier function[51], all of w hich appear to p revent the gu t-derived toxic substances into the liver.

Accord ing to the inconsisten t resu lts, lim ited in form ation is available abou t the accu rate ro le of BCAAs in the m etabolic d iseases; it m ay be valuab le to develop d iagnostic biom arkers fo r NAFLD. Fu rther research exam in ing p ro teo ly tic ferm entation m ay be vital to understand the interaction betw een the BCAAs and NAFLD.

BILE ACIDS

Bile acids are not d irectly p roduced by the in testinal m icrobiota; rather, they are m ain ly synthesized in the liver by using cholesterol as the substrate. Bile acids can be decon jugated and dehyd roxy lated by the gu t m icrobiota, and the en terohepatic circu lation of bile acids, w hich are reabsorbed and retu rned to the liver via the portal vein, perform m any bio logical functions involved in lip id and glucose m etabolism,and are linked to the pathogenesis and treatm en t of NASH. In an early clinical trialusing Danning Pian (a trad itional Ch inese m ed icine that regu lates bile acid m etabolism) to treat NAFLD, clinical sym p tom s, serum alanine transam inase levels,blood lip id p rofiles, and u ltrasound-based fatty liver w ere significantly im p roved after th ree m onths o f treatm en t[52]. Stud ies show that patients w ith NASH exhibit alterations in their bile acid p rofile. The serum levels of bile acids w ere show n to be elevated in patien ts w ith NASH, includ ing the m ore hyd rophobic and cy totoxic secondary species; th is in creased bile acid exposu re m ay be invo lved in the pathogenesis of NAFLD[53]. Fu rtherm ore, another clinical stud y dem onstrated that increased bile acid s w ere significan tly associated w ith higher grades of heap tic steatosis (tau ro cho late), lobu lar (g ly cocho late) an d p o rta l in flamm ation(tau rolithocholate), and hepatocyte ballooning (tau rocholate), w hile the con jugated cho late and tau rocho late d irectly and secondary to p rim ary bile acid ratio was inversely correlated to NAFLD activity score[54]. These resu lts ind icated a relationship betw een the specific bile acids and the histological features of NASH.

Obesity is strongly associated w ith NAFLD and HCC[55]. Recently, deoxycholicacid(DCA) and the senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP) axis w ere found to have crucial ro les in p rom oting obesity-associated HCC in m ice; obesity indu ces alterations in the gu t m icrobiota and con tribu tes to the increase in DCA, w hich can cause DNA dam age. M oreover, the en terohepatic circu lation of DCA p rom otes the SASP in hepatic stellate cells, w hich consequently secrete various in flamm atory and tum or-p rom oting factors in the liver. Hence, HCC developm ent was exacerbated in m ice after exp osu re to th is chem ical carcinogen[56]. Th is w ork in ferred that m ain taining a balanced intestinal m icrobiota shou ld be advocated, and w eight loss m ay be an effective m ethod.

In add ition, bile acid s are ligand s for the nuclear recep tor farnesoid X recep tor(FXR). FXR-m ed iated signaling has beneficial effects on hep atic lip id and carbohyd rate m etabolism, and this signaling pathw ay also m odu lates p rim ary bile acid syn thesis in the liver. A p revious study found that the serum concen tration o f bile acid s was increased in patien ts w ith NAFLD, and the FXR an tagon istic deoxycholic acid was also increased, w hereas the agonistic chenodeoxycholic acid and the serum level o f fibrob last grow th factor 19 (FGF 19) w ere decreased in NAFLD;these alterations contribu te to the supp ression of hepatic FXR-m ed iated and fibroblast grow th factor recep tor 4-m ed iated signaling, thereby exacerbating NAFLD[57]. This study ind icated that targeting FXR signaling m ight be help fu l to the in tervention of NAFLD. Fan et al. reported that u rsodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) com bined w ith a lowcalorie d iet had therapeu tic effects on steatohepatitis in rats[58]. A clinical stud y dem onstrated that patien ts w ith NASH w ho w ere treated w ith obeticholic acid (an activator of FXR) exhibited im p rovem ents in liver fibrosis, hepatocellu lar ballooning,steatosis, and lobu lar in flamm ation, although the long-term benefits and safety of this d rug treatm ent require fu rther clarification[59]. New er synthetic FXR agonists that are cu rrently being investigated m ight cause few er side effects and exert m ore pow erfu l effects against NASH[60]. Excep t for FXR, bile acids are ligands for the cell m em brane G-p rotein-coup led bile acid recep tor 1 (know n as Takeda G-p rotein-coup led recep tor 5 [TGR5]). TGR5 can regu late in flamm ation and g lucose hom eostasis in the liver,w hich m ay be associated w ith the release of GLP-1 and the inhibition of the NLRP3 in flamm asom e; m eanw hile, the activation of TGR5 resu lts in sustained w eight loss,im p roved hepatic steatosis, rem itted insu lin resistance, and increased energy expend itu re in m ice[61,62]. Nagahashi et al[63]found that the con jugated bile acid s can activate the ERK 1/2 and AKT signaling pathw ays via sphingosine 1-phosphate recep tor 2 (S1PR2) in roden t hepatocy tes and in vivo to regu late hepatic lip id m etabolism. Overall, bile acids are im portant substances for comm unication betw een the liver and the gu t; therefore, therapeu tically targeting bile acid-related pathw ays w arrants further exp loration.

TRIMETHYLAM INE

The nu trien t cho line was first classified as an essen tial nu trien t due to its physiological function in the p revention of NAFLD[64]. Choline deficiency can lead to NAFLD; thus, a choline-deficien t d iet is w idely used in anim al m odels of NASH[65].Choline is m ain ly obtained from the d iet, and stud ies have show n that choline was m etabolized to trim ethy lam ine (TMA) by the gu t m icrobiota includ ing Proteus penneri,Escherichia fergusonii, Proteus m irabilis, and other bacteria w hich can cu t the C-N bond of choline[66,67]. TMA is absorbed into the liver via the portal vein and oxid ized by hepatic flavin-containing m onooxygenases into trim ethy lam ine-N-oxide (TMAO)[68].TMAO is found to con tribu te to m any m etabolic d iseases, such as card iovascu lar d iseases, type 2 d iabetes m ellitus, and NAFLD. A clinical study found that thecircu lating levels of TM AO w ere inversely associated w ith the severity of NAFLD; in particu lar, the serum levels of TM AO, choline, and the betaine/choline ratio w ere show n to be ad versely associated w ith the scores of steatosis and total NAFLD activity. M oreover, the severity of NAFLD was independently correlated w ith higher serum levels of TM AO, low er levels of betaine, and a low er ratio of betaine/choline[69].A lthough the d irect m echanism s th rough w hich TM A is involved in the onset and p rog ression o f NAFLD requ ire fu rther investigation, ano ther clin ical stud y dem onstrated that the serum levels o f TM AO increased along w ith BM I and w ere strongly associated w ith the fatty liver index, suggesting that a specific cu t-off value of serum TM AO m ight help to identify subjects w ho are at high risk for NAFLD[70].Anim al experim en ts show ed that in HFD-fed 129S6 m ice, the im paired g lucose hom eostasis and NAFLD occu rred, w hich w ere associated w ith d isrup tions in choline m etabolism; m eanw hile, the circu lating p lasm a levels of phosphatidy lcholine w ere low er, and the u rinary excretion of m ethy lam ines was higher, ind icating the crucial role of the m etabolic balance of choline by the gu t m icrobiota[71]. In add ition, p revious experim en ts dem onstrated that supp lem entation w ith TM AO along w ith an HFD exacerbated im paired glu cose to lerance, obstructed the hepatic insu lin signaling pathw ay, and caused ad ipose tissue in flamm ation in m ice[72]. M oreover, blocking the TM AO-p roducing enzym e flavin-containing m onooxygenase 3 (FMO 3) can regu late obesity and the beiging of w hite ad ipose tissue[73]. There are also inconsistent resu lts show ing that supp lem entation w ith TM AO in HFD-fed m ice attenuated im paired glucose tolerance and increased insu lin secretion. Therefore, the effects of TM AO on NAFLD m igh t be a doub le-edged sw ord[74]. In ad d ition, TM AO can in fluen ce cholesterol transport, thereby reducing the synthesis of bile acids and decreasing the p roduction of very low-density lipop rotein (VLDL)[75-77]. In research on other d isease,the inhibition of TM A p rodu ction exhibited beneficial effects on card iom etabo lic d iseases[67]. Therefore, fu rther w ell-designed stud ies are needed to exp lore the effects of TMA on m etabolic synd rom e and NAFLD.

TRYPTOPHAN METABOLITES

In add ition to the aforem entioned gu t m icrobiota-derived m etabo lites, tryp tophan m etabolites have been show n to affect the developm ent of NAFLD. Indoles are the m ain tryp tophan-derived gu t bacterial p roducts, w hich include indole-3-acetic acid(I3A), indole p rop ionic acid (IPA), indole-3-lactic acid, indole-3-carboxy lic acid, and tryp tam ine, m ain ly p roduced by Bacteroides, Eubacterium, and Clostridium[18]. I3A and tryp tam ine reduced the p roduction of p ro-in flamm atory cy tokines by m acrophages and inhibited m acrophage m igration to m onocy te chem oattractan t p rotein-1. In add ition, I3A cou ld alleviate cytokine-m ed iated lipogenesis in hepatocy tes via the activation o f the ary l-hyd rocarbon recep tor[78]. This study suggests that I3A and tryp tam ine are crucial m etabolites that m ed iate host-m icrobiota crosstalk. Fu rther stud ies are w arranted, includ ing anim al experim ents and clinical investigations, to determ ine w hether I3A and tryp tam ine can effectively alleviate NAFLD.

Obesity is definitely associated w ith the m orbid ity of NAFLD, and supp lem ent of IPA obviously reduced w eight gain in anim al experim ents[79]. Previous w ork show ed that IPA cou ld scavenge free rad icals and reduce oxidative stress[79], and IPA was though t to be a cand idate for treatm ent of m etabolic d isorders as for its beneficial effects on glucose m etabolism and insu lin resistance[80]. Besides, IPA was found to be low er in obese sub jects, and the elevation of p lasm a IPA level im p roved intestinal barrier function in vitro and in vivo through the com bination of IPA and p regnane X recep tor[81,82], w hich in tu rn inhibited the endotoxin-induced TLR4 signaling and im p roved tissue in flamm ation. Taken all together, fu rther basic and clinical research on the tryp tophan-derived m icrobial m etabolite m ay be crucial for understand ing their im p lications in obesity and NAFLD.

CONCLUSION

NAFLD has becom e the m ost comm on ch ronic liver d isease w o rldw ide. The interactions betw een the gu t m icrobiota and NAFLD have been w idely investigated,and advances in understand ing the m olecu lar m echanism s underlying the gu t-liver in teractions are critical to the developm en t of non-invasive serum biom arkers and targeted therap ies for NAFLD and NASH. To date, the p recise association betw een the gu t m icrobiota and NAFLD, as w ell as an accu rate definition of a healthy gu t m icrobiota, are still d ifficu lt to conclude; how ever, the gut m icrobiota is undoubted ly a contribu ting pathogenic factor in NAFLD, and the m icrobial m etabolites serve as akey bridge betw een the gut m icrobiota and NAFLD via the gu t-liver axis.

A lthough alterations in m icrobial m etabolites m ay be rem arkab le therapeu tic targets or excellen t biom arkers for NAFLD, conclusions from d ifferen t stud ies are inconsisten t due to num erou s un con tro llab le factors that in fluence the resu lts.Therefore, unified research stand ard s, detection m ethod s and cond itions, and evaluation app roaches shou ld be established. On the other hand, translational and p recision stud ies includ ing a sing le species or a specific bacterial group, and a single signaling p athw ay m o lecu le associated w ith bacterial m etabo lism shou ld be em p loyed for im p rovem en ts o f hum an health. In ad d ition, a larger and m ore com p rehensive clinical cohort from the w orld is ind ispensab le. D ifferen t races,environm ents, and genetic backgrounds shou ld be effectively d istinguished, w hich w ou ld help to obtain m ore accu rate, stab le, and ap p licab le resu lts. H opefu lly,ind ivid ualized treatm en t for NAFLD targeting the gu t m icrobiota or m icrobial m etabolites w ill be revealed in the near fu tu re.

World Journal of Gastroenterology2019年17期

World Journal of Gastroenterology2019年17期

- World Journal of Gastroenterology的其它文章

- Recent advances in gastric cancer early diagnosis

- Evolving screening and surveillance techniques for Barrett's esophagus

- Proton pump inhibitor: The dual role in gastric cancer

- Herbs-partitioned moxibustion alleviates aberrant intestinal epithelial cell apoptosis by upregulating A20 expression in a mouse model of Crohn’s disease

- Analysis of the autophagy gene expression profile of pancreatic cancer based on autophagy-related protein microtubule-associated protein 1A/1B-light chain 3

- Clinical value of preoperative methylated septin 9 in Chinese colorectal cancer patients