西藏色季拉山公路沿线PAHs分布、来源及风险

党天剑,陆光华,薛晨旺,孙文青

西藏色季拉山公路沿线PAHs分布、来源及风险

党天剑,陆光华*,薛晨旺,孙文青

(西藏农牧学院水利土木工程学院,西藏 林芝 860000)

分别于2017年3月和12月沿色季拉山318国道采集表层土和冷杉(Mill.)样品,测定了多环芳烃(PAHs)的含量.表层土和冷杉叶中∑16PAHs的含量范围分别为30.21~366.94ng/g dw和39.53~236.42ng/g dw,组成以低环(2、3环)为主.通过特征单体比值法和主成分分析法分析表明,色季拉山PAHs主要来源于化石燃料和生物质的燃烧,同时也受到车辆石油泄漏和大气远距离传输的影响;通过反向气团轨迹判断,色季拉山PAHs大气传输污染主要来自于印度次大陆.色季拉山公路沿线土壤中PAHs的终生致癌风险值均低于1×10-6,说明对当地居民的致癌风险较小.

表层土;冷杉叶;PAHs;源解析;风险评价

多环芳烃(PAHs)是重要的环境污染物之一,因其致癌、致畸和致突变性而倍受关注[1-2].PAHs具有持久性和半挥发性,可长期存在于各环境介质中,并通过水、大气或其他介质在全球范围内迁移.如今,除了人类活动密集的大城市以外[3-4],在人烟稀少的两极地区[5-6]、高山地区[7]和青藏高原[8-9]均检测到PAHs的分布,高寒地区因存在高山冷凝捕作用,从而可能成为PAHs的储蓄区.

PAHs通过大气在全球范围内传输,并通过干湿沉降至地面.地表土直接接受干湿沉降的PAHs,环境中90%以上的PAHs存储在土壤中[10],同时土壤中PAHs还可以通过土壤扬尘、皮肤接触等对人体健康造成威胁[11],其潜在危害也不容忽视.冷杉叶同松针一样,比表面积大且表层蜡脂含量高,对PAHs等污染物有较好的富集作用,已被很多学者用于环境中污染物的生物指示和监测评价[12-15].

青藏高原平均海拔高于4000m,人烟稀少,几乎没有工业污染,是用来研究PAHs大气传输的良好背景区域.近几年,随着旅游业的发展,越来越多的游客和车辆进入高原,人类活动的影响日益明显.藏东南色季拉山拥有原始冷杉林,本研究通过分析冷杉叶和土壤中PAHs的含量水平,阐明其分布特征,解析其来源,在此基础上评估其风险水平.

1 材料与方法

1.1 试剂

萘(Nap)、苊烯(Acy)、(Ace)、芴(Flu)、菲(Phe)、蒽(Ant)、荧蒽(Fla)、芘(Pyr)、苯并[a]蒽(BaA)、屈(Chr)、苯并[b]荧蒽(BbF)、苯并[k]荧蒽(BkF)、苯并[a]芘(BaP)、茚并[1.2.3-cd]芘(InP)、二苯并[a.h]蒽(DBA)、苯并[g.h.i]苝(BgP)等16种PAHs标准溶液和Ace-d10、Phe-d10和Chr-d12等3种回收率指示物均购买于百灵威科技有限公司(北京);固相萃取小柱(CNWDOND Si 1g/6mL)购于上海安谱实验科技股份有限公司;正己烷、二氯甲烷、甲醇和丙酮均为色谱纯,购买于西陇科学股份有限公司(广东汕头).

1.2 样品采集

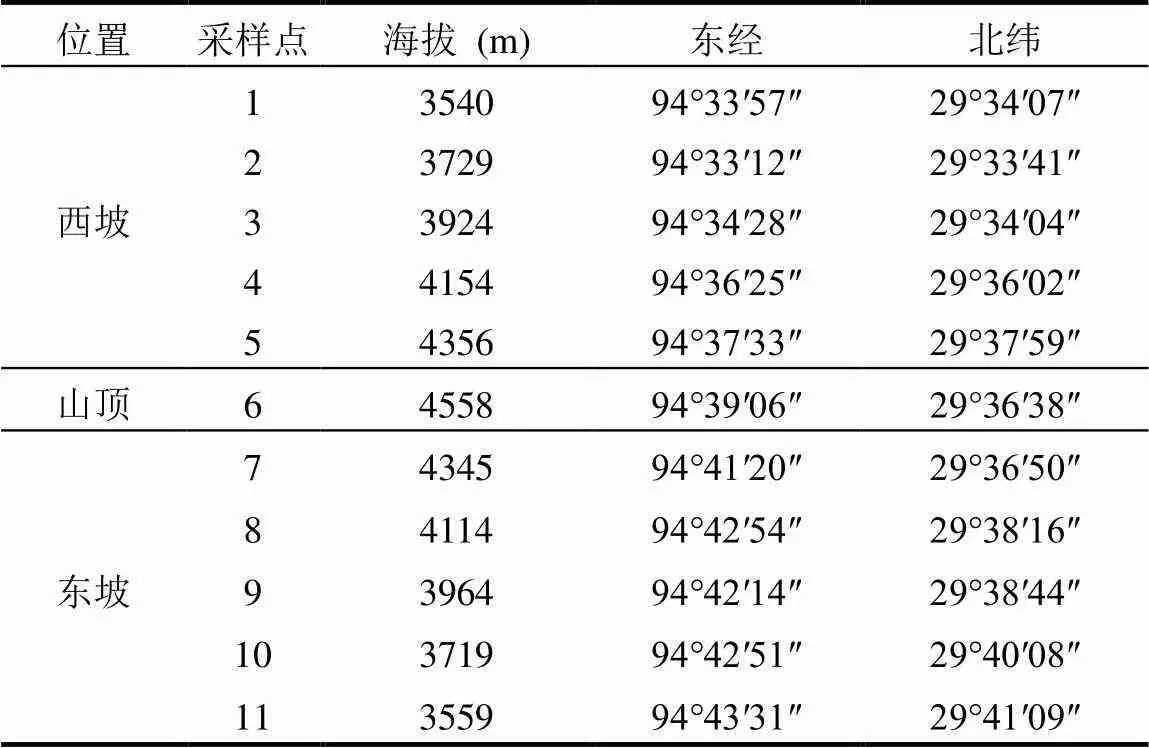

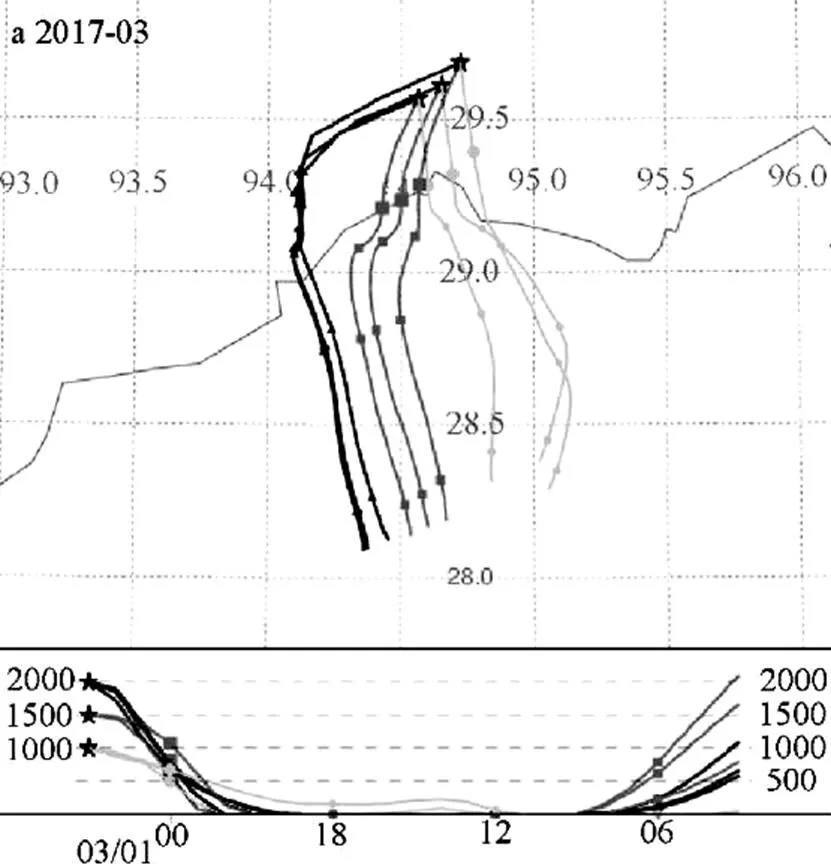

分别于2017年3和12月,沿318国道海拔每升高200m设置1个采样点,在东坡、西坡和山顶共设11个采样点(图1),点位信息见表1.

表层土采用5点采样法采样,直径取20m,深度取0~20cm,在每个采样点用洁净不锈钢铲采集5个土壤子样,混合均匀后用4分法缩分,置于聚乙烯密封袋,运回实验室,-20℃冷冻后真空冷冻干燥.选取3年生冷杉叶,采样高度为3~5m,采自4~5棵不同的冷杉树,混匀后包入经处理的铝箔中,用聚乙烯塑料袋封装,-20℃冷冻后进行真空冷冻干燥.将干燥后的土样和冷杉样剔除杂物,研磨,过60目筛后密封装袋备用.

表1 采样点位信息 Table 1 Information of sampling sites

1.3 样品预处理

称取冻干表层土样品5g,与0.5g活化的铜粉充分混合,加入到22mL萃取池中,剩余孔隙用硅藻土填充.用加速溶剂萃取仪(ASE350, Dionex,美国)萃取,萃取剂为二氯甲烷/正己烷(1:1,/)混合溶液,萃取条件为:萃取温度100℃,系统压强10.3´106Pa,加热时间5min,静态提取时间5min.提取液于旋转蒸发仪上浓缩至近干,加入3mL正己烷转换溶剂.萃取液经固相萃取柱净化,用5mL二氯甲烷/正己烷(2:3,/)洗脱,洗脱液氮吹浓缩至近干,再用1mL正己烷/丙酮(9:1,/)混合液定容,过0.22μm有机相滤膜后转入进样瓶中待测.

称取冻干冷杉叶样品2g,加入到22mL萃取池中,加入3g中性氧化铝粉末,剩余孔隙用硅藻土填充.采用加速溶剂萃取仪萃取,条件与土样相同.在提取液中加入10mL浓硫酸,静置30min后取上层清液于旋转蒸发仪上浓缩至近干,后续处理与土样相同.

1.4 仪器分析

采用GC-MS/MS(ThermoFisher Scientific, USA)进行PAHs定量分析.色谱柱为HP-5MS(30.0m× 250.0μm×0.25μm).进样口温度260℃,柱初始温度60℃,持续1min,以15℃/min升温至120℃,持续1min,再以20℃/min升温至180℃,之后以5℃/min升温至290℃,持续5min.载气为氦气,流量1mL/min,不分流进样,进样量为1μL.质谱条件:离子源温度260℃,接口温度290℃,扫描模式:SIM.

为了保证实验方法可靠性,实验通过方法空白、基质加标和样品平行等来进行质量控制和保证.空白样品中未检出目标污染物.土壤和冷杉样品基质加标回收率分别为77.8%~122%和74.8%~111%,方法检出限分别为0.01~0.16,0.13~0.33ng/g.

2 结果与讨论

2.1 PAHs含量水平

色季拉山表层土中∑16PAHs在3和12月分别为101.27~350.33,30.21~366.94ng/g dw,平均值分别为187.58,83.09ng/g dw(表2),与长白山PAHs含量接近[19],远低于中国西南山区[18]和欧洲山脉[20],但高于青藏高原其他背景区域[16-17].色季拉山是旅游观光胜地,且距离林芝市不远,受人类活动影响较大.冷杉叶中∑16PAHs在3和12月分别为104.55~236.42, 39.53~119.96ng/g dw,平均值分别为194.05, 75.47ng/g dw,与Yang等[21]在藏东南研究结果相近,也与德国科隆2002年松针中PAHs含量相似[23],但远低于南京、大连松针中PAHs的浓度[13,22].植物叶片中污染物主要来源于大气亲脂性有机污染的富集,各地区PAHs浓度差异可能主要与当地大气污染水平有关.

表2 本研究与其他地区各介质中PAHs的含量 Table 2 Concentrations of PAHs in different media from this study and other areas

2017年3月土壤和冷杉叶中PAHs的浓度水平均略高于2017年12月.在12月土样中,Ace、Acy和An未检出,其他PAHs组分检出率为100%.12月色季拉山几乎没有人类活动痕迹,污染主要来源于大气传输,以中、低环PAHs为主;而3月开始游客逐渐增多,人类活动增加,PAHs检出种类增多、浓度升高.西坡PAHs浓度略高于东坡,但PAHs含量水平与海拔高度没有显著相关.

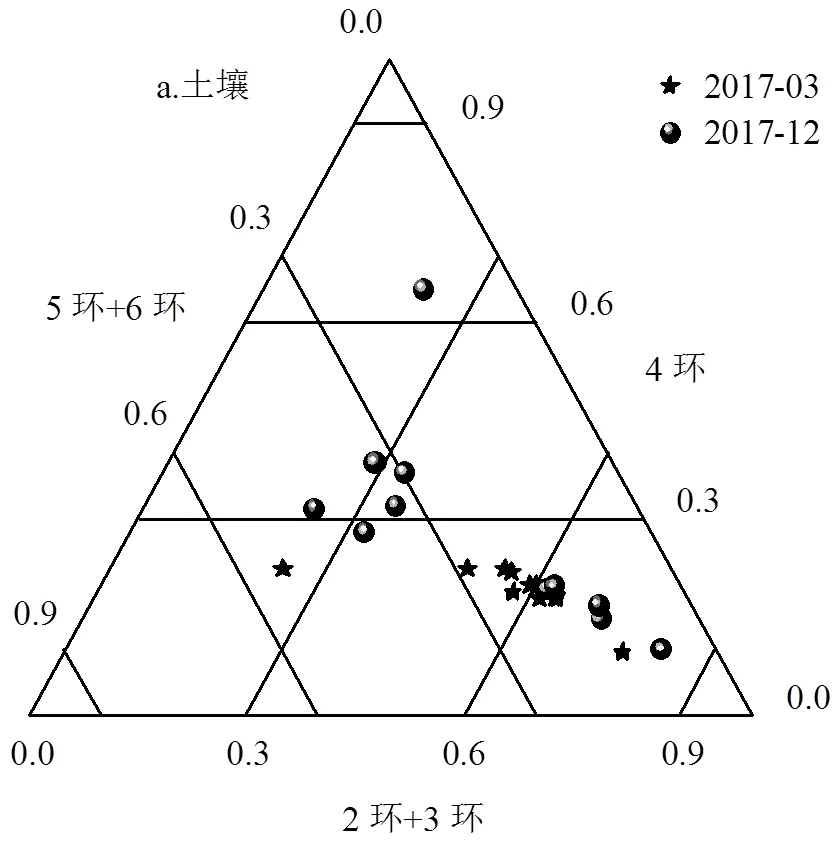

2.2 PAHs组成特征

根据苯环数的不同,可将PAHs划分为低环(2+3环)、中环(4环)和高环(5+6环)[25].色季拉山检出的PAHs结构特征如图2所示,土样除3月S8点高环PAHs含量最高,达到53.63%,总体仍以低环PAHs为主,3和12月土样中低环PAHs占比分别达到23.97%~77.21%和21.77%~82.29%.3月土壤中单体PAHs占比以Nap和Phe为主,分别占总量的28.02%和15.06%,而12月中Chr相对含量最高,达到21.9%,余下依次为Nap和Phe,分别占总量18.99%和12.18%.冷杉叶PAHs同样以低环为主,在3和12月分别占到39.92%~73.10%和32%~70.56%,3月冷杉叶中单体PAHs占比以Nap和Phe为主,分别占总量51.68%和7.45%,12月中Phe占比最高,其次为Pry和Nap,分别占总量21.56%、19.39%和12.09%.总体上各介质中PAHs组成为低环>中环>高环.

2.3 PAHs来源解析

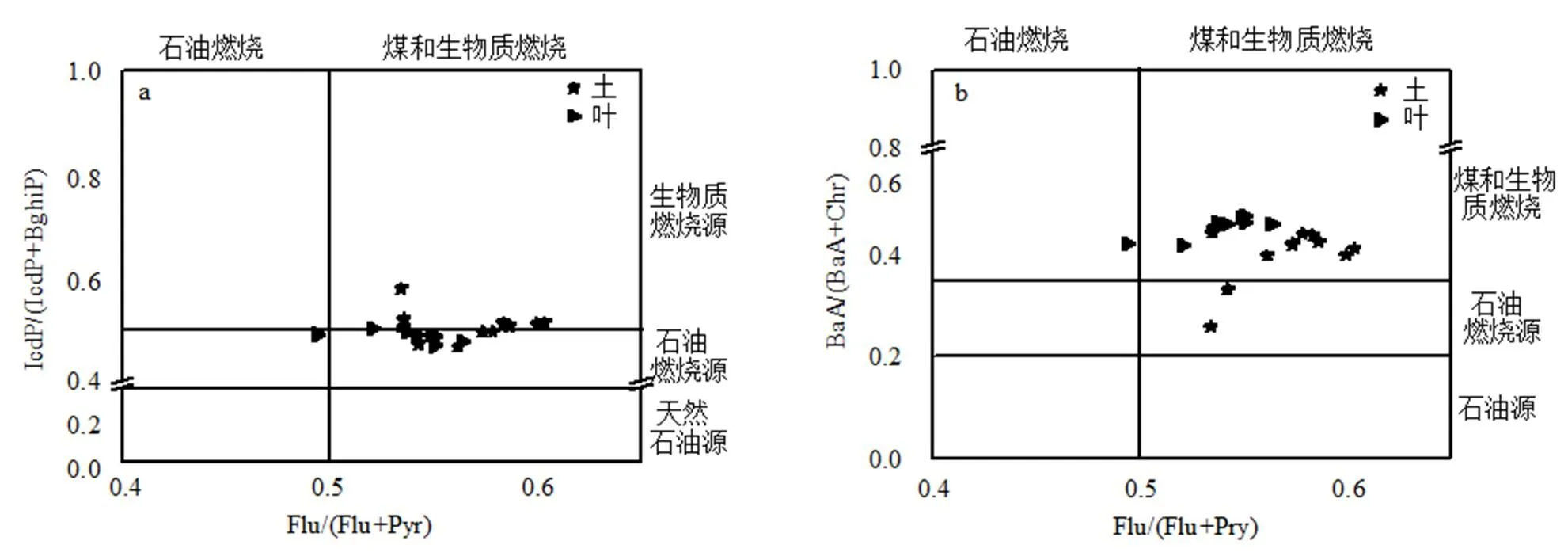

2.3.1 特征组分比值法,燃烧源种类和燃烧条件不同,产生的PAHs组分和相对含量也不同,因此PAHs特征组分之间的含量比可以用来识别PAHs的污染来源[22].本研究使用An/(An+Phe)、Flu/(Flu+Pyr)、BaA/(BaA+Chr)和IcdP/(IcdP+BghiP)来解析色季拉山PAHs的来源.

An/(An+Phe)小于0.10表明存在石油源,大于0.10表示燃烧源占主导地位;Flu/(Flu+Pyr)=0.50通常被定义为石油燃烧过渡点,比率大于0.50,表明来源于生物质和煤燃烧,比率在0.40~0.50之间符合液体化石燃料燃烧(车辆油和原油)的特征[26]. BaA/ (BaA+Chr)比率大于0.35,表明来源于煤、草和木的燃烧,0.20~0.35之间表示源于石油燃烧,小于0.2时为石油源[9].IcdP/(IcdP+BghiP)比率小于0.2,表明来源于天然石油源;在0.2~0.5之间,则为石油燃烧源;大于0.5表示来自于生物质燃烧(草、木材、煤)[27].

如图3所示,各介质中Flu/(Flu+Pyr)比值多数落在>0.5的区间,说明其来源为煤和生物质燃烧,也有少量点分布在0.4~0.5之间,表明也受到了石油燃烧的影响.3月表层土和冷杉叶中An/(An+Phe)比值判断结果均在>0.1的区域,表明燃烧源占主导地位.各介质IcdP/(IcdP+BghiP)的比值大多分布在>0.5的区域,表明主要来源还是生物质的燃烧,但也有部分点分布在0.2~0.5区间,说明石油燃烧也贡献了一定的PAHs.3月各介质BaA/(BaA+Chr)的比值判断结果均大于0.2,表明其主要受燃烧源的影响;但12月表层土和冷杉叶中有73.68%的采样点BaA/(BaA+Chr)的比值小于0.2.结果表明,不同季节样品中特征比值相差较大,一方面是由于色季拉山PAHs来源复杂,另一方面也说明仅利用特征比值进行PAHs来源解析存在局限.

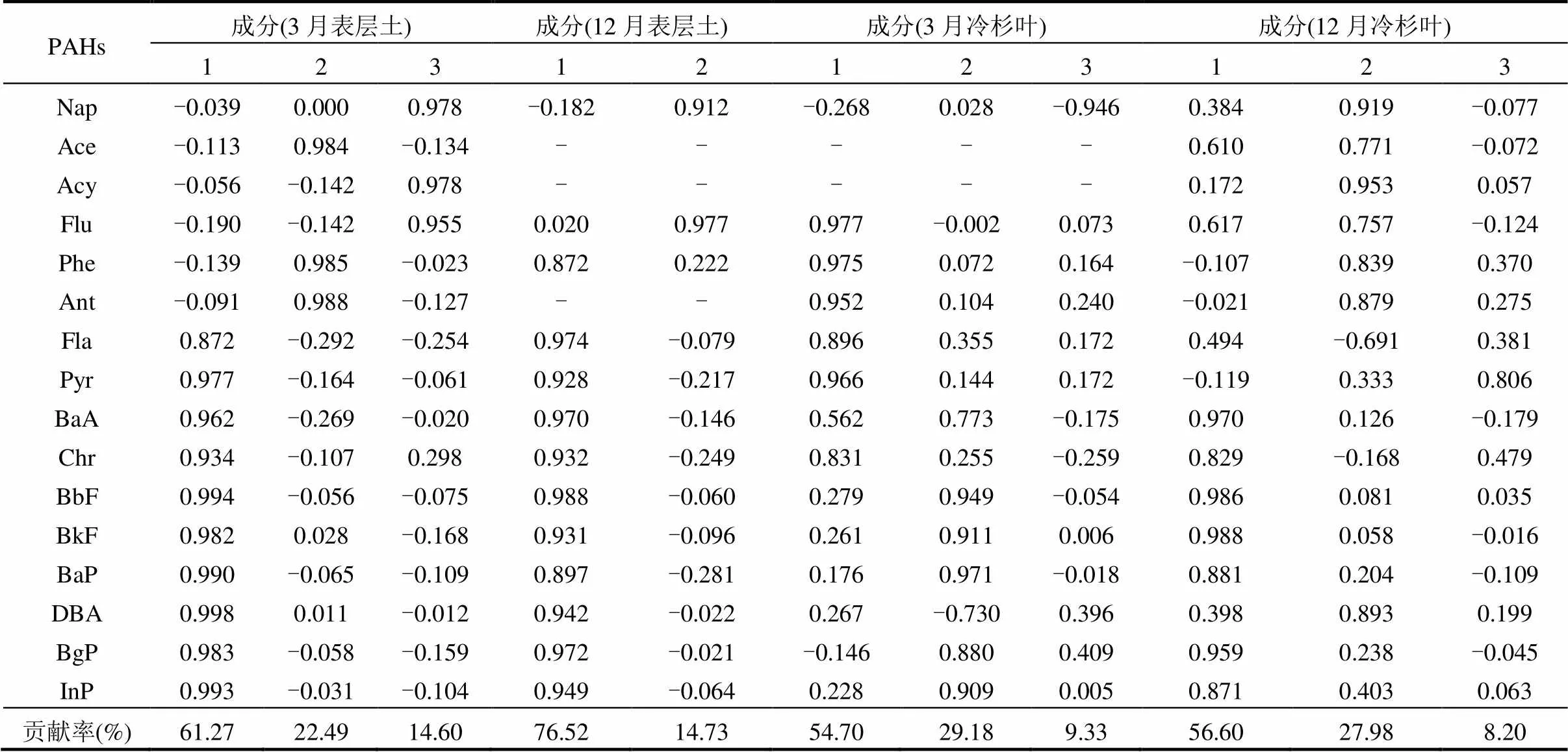

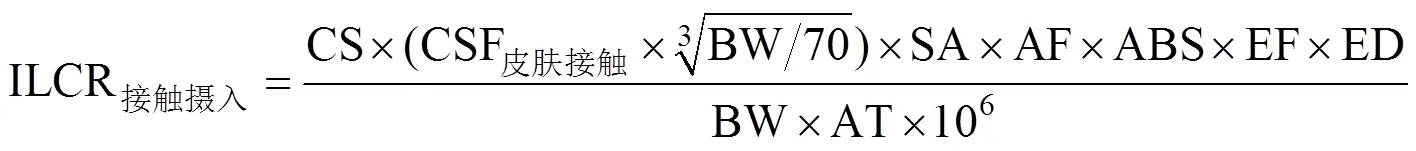

2.3.2 主成分分析 为了进一步解析色季拉山PAHs的来源,采用主成分分析法定量分析了各污染源对色季拉山PAHs的贡献.提取特征根大于1的因子,旋转后的主成分矩阵见表3.土壤和冷杉中16种PAHs包含的信息可集中在2个或3个主成分中,且各介质所提取的主成分总方差贡献均超过80%.

土壤和冷杉叶中主成分1贡献率范围为54.70%~76.52%,其中Pyr、BaA、Chr、BbF、BkF、BaP、DBA、BgP、InP载荷突出,An、Fla载荷也较高.Fla、Pyr、BaA和Chr等4环及以上PAHs主要来源于煤的燃烧[28-29];BaA、BgP和InP是汽车尾气的标志性组分[30-31],BaK则是柴油机排放的主要PAHs[32];而An不仅是石油源的代表性化合物[33],也是木材等不完全燃烧的代表物质[34].主成分2和3贡献率分别达到14.73%~29.18%和8.20%~14.60%,其中2环的Nap载荷突出,Nap不稳定、易挥发,可通过大气远距离传输,表明存在外来源的污染[35],此外还受石油泄漏污染的一定影响[33,36].Ace、Acy、Flu和Phe在因子2、3中均有较高载荷,其中Ace是石油源的代表性化合物[36],Acy是薪柴燃烧的标志物[37],Flu和Phe则主要来源于焦炉排放[34,38].

主成分分析结果表明,色季拉山PAHs污染主要受化石燃料和生物质燃烧的影响.除燃煤外,当地居民还习惯用木柴、牛粪等生物质作燃料,符合当地能源利用情况.色季拉山口是旅游景点,也是去林芝鲁朗小镇的必经之路,每年有大量游客驾车经过,本研究又主要沿318国道采样,所以交通污染源贡献也较大.此外,从主成分2、3的贡献来看,色季拉山PAHs还受石油源和大气远距离传输的影响,石油源主要受旅游车辆燃油泄漏影响,青藏高原作为世界第三极,而色季拉山最高海拔达到4550m,也符合高山冷凝捕条件.

2.3.3 反向气团轨迹分析 为了追踪色季拉山PAHs的大气传输来源,利用美国国家海洋和大气管理局(NOAA)空气资源实验室和澳大利亚气象局联合研发的HYSPLIT-4模型分析了到达色季拉山3个采样点(山顶和两边山脚)距离地面1000,1500和2000m高处的气团运动轨迹(图4).与青藏高原中、北部在6~9月开始受印度季风的影响不同[39],色季拉山地处藏东南地区,在2月起就开始受印度季风影响,南风将印度和孟加拉国等地区的污染物通过雅鲁藏布江大峡谷传输到青藏高原南部,并于6月结束;7~8月主要受来自青藏高原内部气团的影响,带来拉萨、林芝等地区污染物,此外也受到青海、甘肃等内陆省份的影响;从9月~次年1月,则受冬季西风带的影响,这与Chen等[40]提出藏东南地区冬季主要受西部气团影响的结论相似,西风绕道喜马拉雅山脉,将印度北部和巴基斯坦等地区的污染物传输到色季拉山[39].

综上所述,虽然在7,8月色季拉山受到青藏高原内部和内陆省份的影响,但色季拉山气团主要还是受印度季风和冬季西风的影响,而二者皆经过印度次大陆,因此色季拉山PAHs污染主要还是受印度次大陆污染源的远距离传输影响.

表3 方差最大旋转后16种PAHs的主成分因子载荷 Table 3 Factor loading for PAHs on principle component analysis with varimax rotation

注:-为未检出.

2.4 表层土中PAHs的健康风险评估

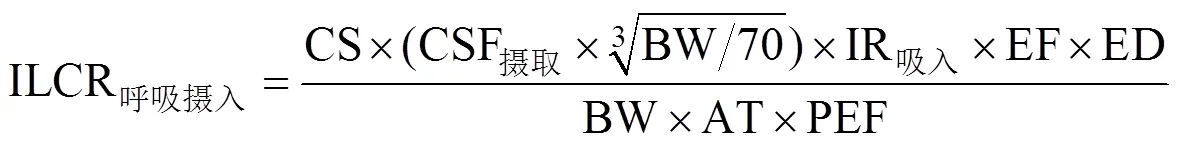

美国环保署将BaA、BbF、BkF、BaP、Chr、DBA和InP等7类PAHs归类为可能的人类致癌物,因此有必要对色季拉山PAHs进行风险评估.本文采用终生致癌风险(ILCRs)模型评估了PAHs通过直接摄入、呼吸摄入和皮肤接触等对儿童、青少年和成人的潜在风险.各暴露途径PAHs致癌风险计算公式如(1)~(3)所示[41].

式中:CS为总的BaP当量(BaPeq), mg/kg;CSF为致癌斜率因子mg/(kg×d);BW为人平均体重kg;EF为暴露频率d/a;IR摄取为土壤摄取速率mg/d;ED为暴露时间a;SA为与土壤接触的皮肤面积cm2/d;AF为土壤的皮肤黏附因子mg/cm2;ABS为皮肤吸收因子;PEF为颗粒物排放因子m3/kg.各参数取值参考文献[41].

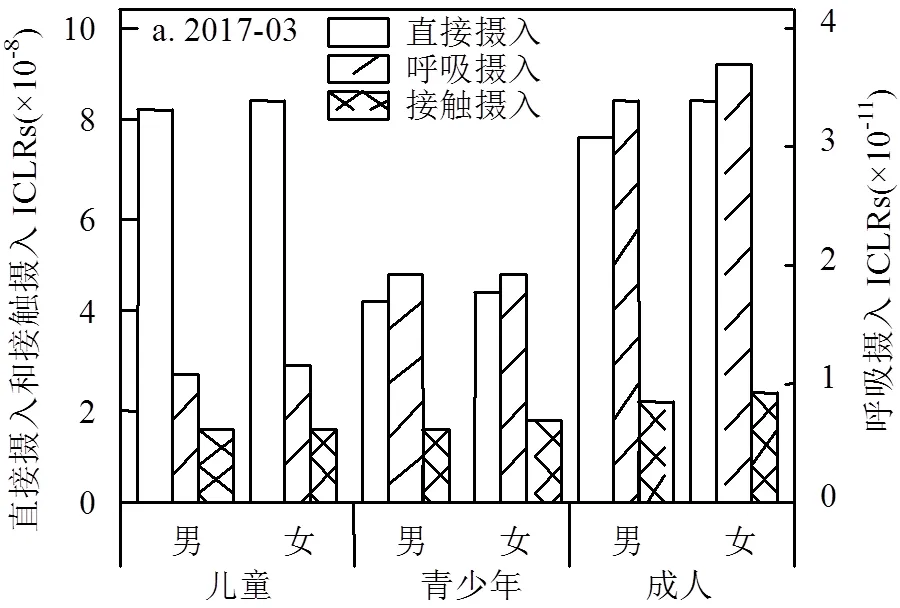

式(1)~(3)计算结果表明,色季拉山PAHs在3和12月通过直接摄入、呼吸摄入和皮肤接触的致癌风险范围分别为:2.82×10-8~2.76×10-7、7.44× 10-12~ 1.20×10-10、1.04×10-8~7.46×10-8和1.97×10-9~ 7.87×10-8、5.20×10-13~3.43×10-11、7.28×10-10~ 2.13×10-8.研究区域土壤中PAHs对不同人群的致癌风险如图5所示.3月色季拉山PAHs通过不同暴露途径对不同人群的影响均高于12月,但PAHs的终生致癌风险影响却类似,均是直接摄入>接触摄入>呼吸摄入.受直接摄入影响最大的是儿童群体,成人群体则受呼吸摄入影响最大,不同群体受皮肤接触摄入影响接近.对不同人群而言,成人受不同暴露途径的总影响最高,其次是儿童,青少年受影响最小.

当ILCRs值在10-6~10-4之间时,被认为存在潜在危险,而ILCRs值£10-6时,可忽略其风险[42].色季拉山不同年龄段人群总ICLRs值均小于1×10-6,因此,色季拉山土壤对当地居民并不存在致癌风险.但随着色季拉山周边城镇和旅游业的发展,色季拉山PAHs污染可能逐渐加重,仍需注意.

3 结论

3.1 藏东南色季拉山公路沿线土壤和冷杉中普遍检出PAHs,含量分别为30.21~366.94,39.53~ 236.42ng/g dw,单体特征以低环为主,其中Nap和Phe含量最高.

3.2 色季拉山PAHs主要来自于化石燃料和生物质的燃烧,这与当地居民生活习惯和旅游业的发展情况相符;同时色季拉山还受到大气远距离传输的影响,主要为印度次大陆的污染输入.

3.3 健康风险评估结果表明,色季拉山土壤中PAHs对当地居民的致癌风险较小.

[1] Tobiszewski M, Namieśnik J. PAH diagnostic ratios for the identification of pollution emission sources [J]. Environmental Pollution, 2012,162(1):110–119.

[2] Maliszewska-Kordybach B, Smreczak B, Klimkowicz-Pawlas A. Concentrations, sources, and spatial distribution of individual polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in agricultural soils in the Eastern part of the EU: poland as a case study [J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2009,407(12):3746–3753.

[3] Wang X Y, Li Q B, Luo Y M, et al. Characteristics and sources of atmospheric polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in Shanghai, China [J]. Environmental Monitoring & Assessment, 2010,165(1-4): 295–305.

[4] Saha M, Maharana D, Kurumisawa R, et al. Seasonal trends of atmospheric PAHs in five Asian megacities and source detection using suitable biomarkers [J]. Aerosol & Air Quality Research, 2017, 17(9):2247–2262.

[5] 马新东,姚子伟,王 震,等.南极菲尔德斯半岛多环境介质中多环芳烃分布特征及环境行为研究[J]. 极地研究, 2014,26(3):285–291.Ma X D, Yao Z W, W Z, et al. Distribution and environment of PAHs in different matrixes on the Fildes Peninsula, Antarctic [J]. Chinese Journal of Polar Research, 2014,26(3):285–291.

[6] Kosek K, Kozak K, Kozioł K, et al. The interaction between bacterial abundance and selected pollutants concentration levels in an arctic catchment (southwest Spitsbergen, Svalbard) [J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2017,622-623:913–923.

[7] Liu J, Wang Y, Li P H, et al. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) at high mountain site in north China: concentration, source and health risk assessment [J]. Aerosol & Air Quality Research, 2017,17(11): 2867–2877.

[8] Wang C, Wang X, Gong P, et al. Long-term trends of atmospheric organochlorine pollutants and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons over the southeastern Tibetan Plateau [J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2018,624:241–249.

[9] 周雯雯,李 军,胡 健,等.青藏高原中东部表层土壤中多环芳烃的分布特征、来源及生态风险评价[J]. 环境科学, 2018,39(3):1413– 1420.Zhou W W, Li J, Hu J, et al. Distribution, sources, and ecological risk assessment of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in soils of the central and eastern areas of the Qinghai-Tibetan plateau [J]. Environment Science, 2018,39(3):1413–1420.

[10] Wild S R, Jones K C. Polynuclear aromatic hydrocarbons in the United Kingdom environment: a preliminary source inventory and budget [J]. Environmental Pollution, 1995,88(1):91–108.

[11] 孙 焰,祁士华,李 绘,等.福建闽江沿岸土壤中多环芳烃含量、来源及健康风险评价[J]. 中国环境科学, 2016,36(6):1821–1829. Sun Y, Qi S H, Li H, et al. Concentrations, sources and health risk assessment of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in soils collected along the banks of Minjiang River, Fujian, China [J]. China Environment Science, 2018,39(3):1413–1420.

[12] Wilcke W. Global patterns of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in soil [J]. Geoderma, 2007,141(3):157–166.

[13] 汪福旺,王 芳,杨兴伦,等.南京公园松针中多环芳烃的富集特征与源解析 [J]. 环境科学, 2010,31(2):503–508. Wang F W, Wang F, Yang X L, et al. Enrichment characteristics and source apportionment of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in pine (Lamb) needles from parks in Nanjing City, China [J]. Environment Science, 2010,31(2):503–508.

[14] Oishi Y. Comparison of moss and pine needles as bioindicators of transboundary polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon pollution in central Japan [J]. Environmental Pollution, 2018,234:330–338.

[15] Yang R, Yao T, Xu B, et al. Distribution of organochlorine pesticides (OCPs) in conifer needles in the southeast Tibetan Plateau [J]. Environmental Pollution, 2008,153(1):92–100.

[16] Yuan G L, Wu L J, Sun Y, et al. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in soils of the central Tibetan Plateau, China: distribution, sources, transport and contribution in global cycling [J]. Environmental Pollution, 2015,203:137–144.

[17] He Q, Zhang G, Yan Y, et al. Effect of input pathways and altitudes on spatial distribution of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in background soils, the Tibetan Plateau [J]. Environmental Science & Pollution Research, 2015,22(14):10890–10901.

[18] Shi B, Wu Q, Ouyang H, et al. Distribution and source apportionment of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in soils and leaves from high-altitude mountains in southwestern China [J]. Journal of Environmental Quality, 2014,43(6):1942–1952.

[19] Zhao X, Kim S K, Zhu W, et al. Long-range atmospheric transport and the distribution of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in Changbai Mountain [J]. Chemosphere, 2015,119:289–294.

[20] Quiroz R, Grimalt J O, Fernandez P, et al. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in soils from European high mountain areas [J]. Water Air & Soil Pollution, 2011,215(1-4):655–666.

[21] Yang R, Zhang S, Li A, et al. Altitudinal and spatial signature of persistent organic pollutants in soil, lichen, conifer needles and bark of the southeast Tibetan Plateau: implications for sources and environmental cycling [J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2013,47(22):12736–12743.

[22] 杨 萍,王 震,陈景文,等.松针生理性质对其富集多环芳烃行为的影响[J]. 环境科学, 2008,29(7):2018–2023.Yang P, Wang Z, Chen J W, et al. Influences of pine needles physiological properties on the PAH accumulation [J]. Environment Science, 2008,29(7):2018–2023.

[23] Lehndorff E, Schwark L. Biomonitoring of air quality in the Cologne Conurbation using pine needles as a passive sampler—Part II: polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAH) [J]. Atmospheric Environment, 2004,38(23):3793–3808.

[24] Holoubek I, KořÍnek P, Šeda, Z, et al. The use of mosses and pine needles to detect persistent organic pollutants at local and regional scales [J]. Environmental Pollution, 2000,109(2):283-292.

[25] Zhu Y, Yang Y, Liu M, et al. Concentration, distribution, source, and risk assessment of PAHs and heavy metals in surface water from the Three Gorges Reservoir, China [J]. Human & Ecological Risk Assessment, 2015,21(6):1593–1607.

[26] Lei X, Li W, Lu J, et al. Distribution of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in snow of Mount Nanshan, Xinjiang [J]. Water & Environment Journal, 2015,29(2):252–258.

[27] Yunker M B, Macdonald R W, Vingarzan R, et al. PAHs in the Fraser River basin: a critical appraisal of PAH ratios as indicators of PAH source and composition [J]. Organic Geochemistry, 2002,33(4):489–515.

[28] Ribeiro J, Silva T, Mendonca Filho J G, et al. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in burning and non-burning coal waste piles [J]. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 2012,199(2):105–110.

[29] Kamal A, Malik R N, Martellini T, et al. Cancer risk evaluation of brick kiln workers exposed to dust bound PAHs in Punjab province (Pakistan) [J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2014,493(5):562– 570.

[30] Peng C, Chen W, Liao X, et al. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in urban soils of Beijing: status, sources, distribution and potential risk [J]. Environmental Pollution, 2011,159(3):802–808.

[31] Simcik M, Lioy P S. Source apportionment and source/sink relationships of PAHs in the coastal atmosphere of Chicago and Lake Michigan [J]. Atmospheric Environment, 1999,33(30):5071–5079.

[32] 朱利中,王 静,杜 烨,等.汽车尾气中多环芳烃(PAHs)成分谱图研究[J]. 环境科学, 2003,24(3):26–29.Zhu L Z, Wang J, Du Y, et al. Research on PAHs fingerprints of vehicle discharges [J]. Environment Science, 2003,24(3):26–29.

[33] Ye B X, Zhang Z H, Mao T. Pollution sources identification of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons of soils in Tianjin area, China [J]. Chemosphere, 2006,64(4):525–534.

[34] 周玲莉,薛南冬,李发生,等.黄淮平原农田土壤中多环芳烃的分布、风险及来源[J]. 中国环境科学, 2012,32(7):1250–1256.Zhou L L, Xue N D, Li F S, et al. Distribution, source analysis and risk assessment of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in farmland soils in Huanghuai Plain [J]. China Environment Science, 2012,32(7):1250– 1256.

[35] 陈 锋,孟凡生,王业耀,等.基于主成分分析-多元线性回归的松花江水体中多环芳烃源解析[J]. 中国环境监测, 2016,32(4):49–53.Chen F, Meng F S, Wang Y Y, et al. The research of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in the river based on the principal component-multivariate linear regression analysis [J]. Environmental Monitoring in China, 2016,32(4):49–53.

[36] Harrison R M, Smith D J T, Luhana L. Source apportionment of atmospheric polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons collected from an urban location in Birmingham, U.K [J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 1996,30(3):825–832.

[37] Khalili N R, Scheff P A, Holsen T M. PAH source fingerprints for coke ovens, diesel and, gasoline engines, highway tunnels, and wood combustion emissions [J]. Atmospheric Environment, 1995,29(4):533–542.

[38] Shen G, Tao S, Chen Y, et al. Emission characteristics for polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons from solid fuels burned in domestic stoves in rural China [J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2013,47(24): 14485–14494.

[39] 谢 婷,张淑娟,杨瑞强.青藏高原湖泊流域土壤与牧草中多环芳烃和有机氯农药的污染特征与来源解析[J]. 环境科学, 2014,35(7): 2680–2690.Xie T, Zhang S J, Yang R Q. Contamination levels and source analysis of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and organochlorine pesticides in soils and grasses from lake catchments in the Tibetan Plateau [J]. Environment Science, 2014,35(7):2680–2690.

[40] Chen Y, Cao J, Zhao J, et al. N-alkanes and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in total suspended particulates from the southeastern Tibetan Plateau: concentrations, seasonal variations, and sources [J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2014,470–471(2):9–18.

[41] Zhang J Q, Qu C K, Qi S H, et al. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in atmospheric dustfall from the industrial corridor in Hubei Province, central China [J]. Environmental Geochemistry & Health, 2015,37(5):891–903.

[42] 张 娟,吴建芝,刘 燕.北京市绿地土壤多环芳烃分布及健康风险评价 [J]. 中国环境科学, 2017,37(03):1146-1153Zhang J, Wu J Z, Liu Y. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in urban green space of Beijing: distribution and potential risk [J]. China Environment Science, 2017,37(3):1146-1153

Distribution, sources and risk of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons along the highway in Shergyla Mountain in Tibet.

DANG Tian-jian, LU Guang-hua*, XUE Chen-wang, SUN Wen-qing

(Department of Water Resources and Civil Engineering, Tibet Agriculture and Animal Husbandry University, Linzhi 860000, China)., 2019,39(3):1109~1116

The surface soil and fir (Mill.) samples were collected in March and December 2017 along the China National Highway 318 in Shergyla Mountain, respectively. The contents of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in the samples were measured. The concentrations of ∑16PAHs ranged from 30.21 to 366.94ng/g (dry weight) in the surface soil and 39.53 to 236.42ng/g (dry weight) in the fir leaves, respectively, and the lower rings (2- or 3-ring) constituents were dominants. The results of diagnostic ratios and principal component analysis suggested that the PAHs mainly originated from the combustion of fossil fuel and biomass, and also affected by oil leaks and atmospheric transmission. The atmospheric transmission pollution of PAHs could mainly result from the Indian subcontinent based on the backward air mass trajectories. The incremental lifetime cancer risks of PAHs in the soils along the highway in Shergyla Mountain were lower than 1×106, indicating a lower carcinogenic risk to the local residents.

surface soil;fir leaves;PAHs;source diagnosis;risk assessment

X53

A

1000-6923(2019)03-1109-08

党天剑(1994-),男,甘肃武威人,西藏农牧学院硕士研究生,主要研究方向为污染生态化学.发表论文3篇.

2018-08-24

国家自然科学基金资助项目(51879228);西藏自治区高等学校科研创新团队项目;西藏农牧学院研究生创新计划项目(YJS2017-04)

* 责任作者, 教授, ghlu@hhu.edu.cn