Relationship between glycemic control and perceived family support among people with type 2 diabetes mellitus seen in a rich kinship network in Southwest Nigeria

Nnenna A. Osuji , Oluwaseun Solomon Ojo , Sunday O. Malomo , Peter T. Sogunle , Ademola O. Egunjobi ,Oluf isayo O. Odebunmi

1. Family Medicine Department,Federal Medical Centre, Abeokuta, Nigeria

Abstract Objective: The practice of diabetes self-care behaviors has been cited as a foundation for achieving optimal glycemic control. Proper motivation of people with diabetes mellitus is, however, needed for the performance of these behaviors. It is therefore pertinent to know if motivation by the family will improve glycemic control in people with type 2 diabetes mellitus. This study aimed to investigate the relationship between glycemic control and perceived family support among Nigerians with type 2 diabetes mellitus.Methods: A cross-sectional study was conduced on 316 adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus who attended a medical outpatient clinic. Data were collected through a pretested intervieweradministered questionnaire and a standardized tool (Perceived Social Support — Family scale).Hemoglobin A 1c level was used as an indicator of glycemic control.Results: The proportion of participants with good glycemic control was 40.6%. Most of the participants (137, 43.8%) had strong perceived family support. Strong perceived family support( P = 0.00001, odds ratio 112.51) was an independent predictor of good glycemic control.Conclusion: This study shows that strong perception of family support is a predictor of glycemic control among the adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus studied. Physicians working in sub-Saharan African countries with rich kinship networks should harness the available family support of people with type 2 diabetes mellitus in their management.

Keywords: Glycaemic control; perceived family support; type 2 DM; kinship; Nigeria

Introduction

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is on the rise around the globe [ 1].Globally, DM affects more than 425 million people, and the number of people with DM may rise to 693 million in 2045 if nothing is done [ 1]. In 2017, Nigeria ranked fourth in Africa,with 1.2 million to 3.9 million people affected by DM [ 1]. The continuous rise in the prevalence of DM has been associated with the consequent increase in the proportion of people with uncontrolled glycemia. Evidence in most studies suggests that less than 50% of DM patients achieve glycemic targets [ 2— 4].

DM has been described as a “ family disease” because of the complex association of all aspects of diabetes with family dynamics [ 5, 6]. Familial risk has been implicated in the development of type 2 DM (T2DM) [ 1]. The emerging epidemic of DM in Africa has been attributed to the industrialization-driven disruption of the African extended family system through rural-urban migration and consequent unhealthy lifestyles [ 1]. The family is also a useful unit of intervention for chronic diseases such as DM [ 5— 8].

DM is a lifelong disease that requires care within and outside the hospital. The care beyond the hospital wall, which is mainly self-care behaviors, is central to DM management [ 9,10]. This is more relevant to DM care in Nigeria, where, in the face of the astronomically increased number of DM patients,there is poor health care use as well as a low physician-patient ratio [ 11]. Self-care practices require behavioral change on the part of patients, and this may be an arduous task without motivation. The institution from where DM patients can get motivation is the family [ 12, 13]. Could the solution to poor glycemic control among DM patients be support from their families?

The results of studies on the relationship between family support and glycemic control among people with DM have not been consistent [ 5— 8, 14, 15]. Some studies have shown that family support improves glycemic control among people with DM [ 8, 14], while another study has reported no effect on glycemic control among them [ 15]. However, most of these studies were not conducted in Africa, where the family is rated high in the value system [ 5— 7, 14, 15]. In addition, most of these studies did not assess perceived family support, which predicts better health outcomes [ 14, 15].

Thus, it is pertinent to look at the relationship between glycemic control and perceived family support in a traditional African setting, where the extended family system is still very common.This study is based on this premise that the authors sought to investigate the relationship between glycemic control and perceived family support among people with T2DM seen in a tertiary hospital located in a rich kinship network in southwest Nigeria.

Research design and methods

Study site

This study was conducted in the medical outpatient clinic of a tertiary hospital in southwest Nigeria. The medical outpatient clinic is one of the specialist clinics that serve as a receiving center for referrals mainly from the general outpatient clinic and other units of the hospital. Health education is given by the nurses and dieticians especially for people with DM and hypertension on each clinic day. Adult male and female patients, including new patients and patients returning for routine follow-up visits, are seen at the clinic.

Study population

The study population comprised adults aged 18 years or older with T2DM attending the medical outpatient clinic of a tertiary hospital in southwest Nigeria.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

All consenting adults with T2DM aged 18 years or older who had been attending the medical outpatient clinic for DM care for at least 1 year were included in the study. Patients with psychiatric illness and critically ill patients were excluded.

Sample size

The sample size was determined with the formula for estimating prevalence from a descriptive study: n = z2pq/ d2[ 16]. A sample size of 316 was obtained with standard normal deviate( z) = 1.96, the proportion of people with T2DM with good glycemic control from a previous study ( p) of 29.3% (0.293) [ 17],and desired level of precision ( d) = 0.05.

Sampling technique

A systematic random sampling technique was used to recruit 316 participants for this study until the sample size was reached. The case f iles of those selected at the end of each clinic were marked with a sticker to avoid duplication.

Data collection

A pretested interviewer-administered questionnaire and a standardized questionnaire were used to collect information on sociodemographic characteristics and the level of perceived family support of the respondents, respectively. Study participants were interviewed alone, without a family member present, by the investigators. The questionnaire consisted of sections on sociodemographic data, information on the level of perceived family support, and blood glucose control.Sociodemographic characteristics consisted of information pertaining to age, sex, marital status, type of family, household size, education level, religion, and ethnic group.

The respondents’ level of perceived family support was assessed with the Perceived Social Support — Family scale of Procidano and Heller [ 18]. It is a 20-item validated selfreport scale which examines how people perceive support,information, and response from their family. Respondents answered “ Yes,” “ No,” or “ I don’ t know” to each question.Each “ yes” answer was scored as 1, while other responses were scored 0. Items 3, 4, 16, 19, and 20 were reverse scored (a“ no” response was scored as 1). Summated scores were used to arrive at a perceived family support score, and the possible range of scores was 0— 20. Scores were categorized as strong perceived family support ( ≥ 11), weak perceived family support (7— 10), and no perceived family support ( ≤ 6). The scale has acceptable validity and reliability. The internal consistency of the scale is 0.88, while the short-term test-retest reliability is 0.83 [ 18].

Glycemic control was assessed by measurement of glycated hemoglobin (hemoglobin A1c) levels. Three milliliters of a venous blood sample for measurement of hemoglobin A1clevel was drawn from the antecubital vein of each participant into a f luoride sample bottle. Hemoglobin A1clevel was determined by the rapid ion exchange chromatographic method (DIALAB,Gieselhaft, Germany). The blood samples were stored at 2° C—8° C and the analysis was done within 5 days of collection. The following formula given by the manufacturer of the kit was used to obtain the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial referenced values: National Glycohemoglobin Standardization Program hemoglobin A1clevel (%) = 0.86 × DIALAB hemoglobin A1clevel (%) + 0.24. Glycemic control was categorized on the basis of the American Diabetes Association criteria as good glycemic control (hemoglobin A1clevel < 7%) and poor glycemic control (hemoglobin A1clevel ≥ 7%) [ 19].

Data analysis

IBM SPSS Statistics (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA) version 22.0 was used for data analysis. Figures and tables were drawn to present data. Means and standard deviations were calculated for continuous variables, while ratios and percentages were calculated for categorical variables as appropriate. The chi-square test was used to test the association between the categorical variables. The level of signif icance was set at P ≤ 0.05. Signif icant independent variables were entered into a logistic regression analysis to determine the independent predictors of glycemic control. The odds ratios(ORs) and 95% CIs for the predictor variables were then calculated.

Ethical considerations

Ethics approval was obtained from the Health Research Ethics Committee of the Federal Medical Center, Abeokuta with reference approval number NREC/08/04/2010. Consent was also obtained from the patients.

Results

A total of 316 participants were recruited from the medical outpatient clinic for the study. Three participants had missing data that precluded analysis; hence data for 313 participants were analyzed, giving a completion rate of 99.05%.

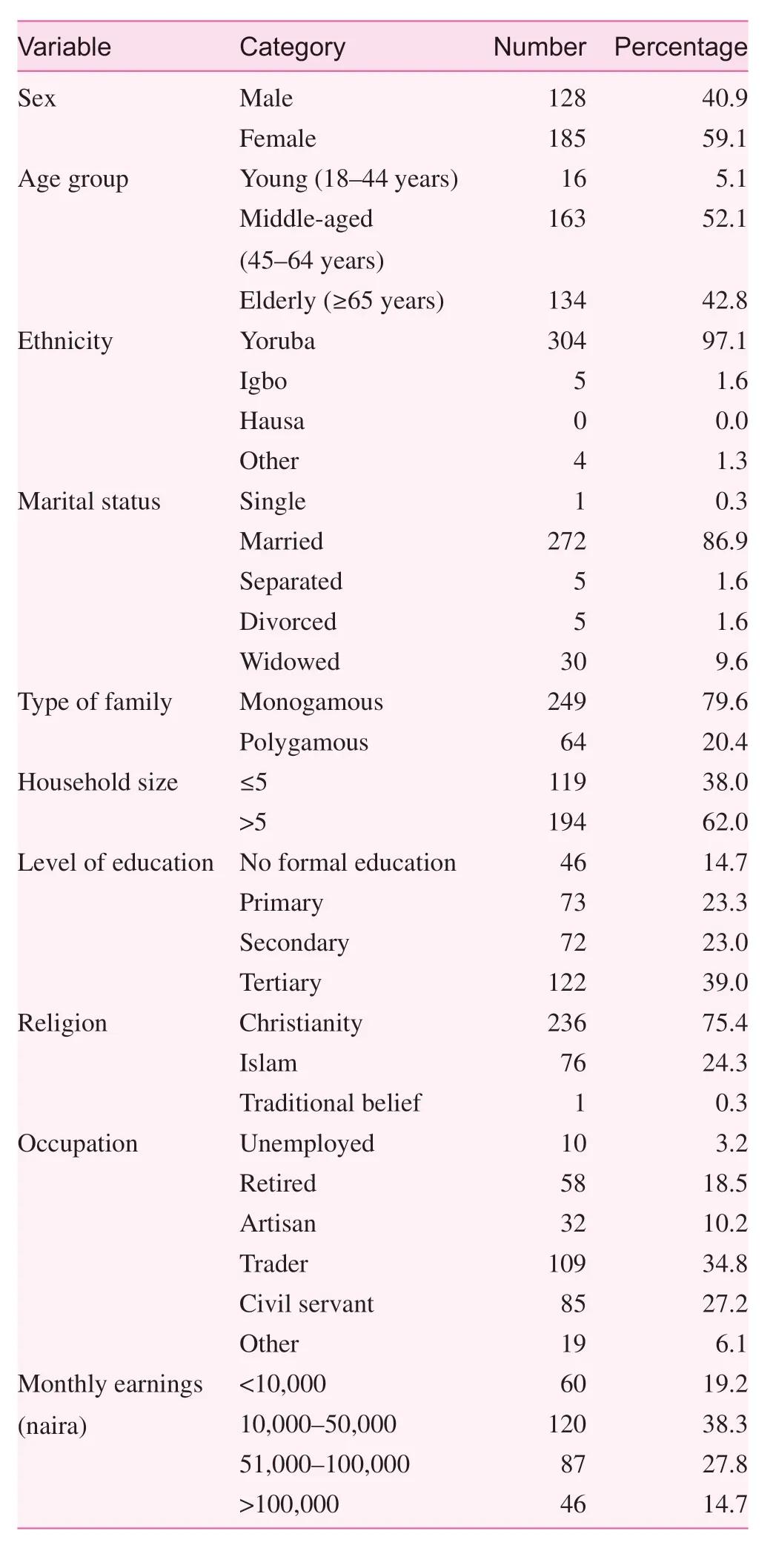

Table 1 shows the sociodemographic characteristics of the study participants. The age range of the respondents was 34— 86 years. The mean age was 60.96 ± 10.1 years. Most of the respondents were in the 45— 64 year age group (163,52.1%). There were more female respondents (185, 59.1%)than male respondents (128, 40.9%), with a male-to-female ratio of 1:1.5.

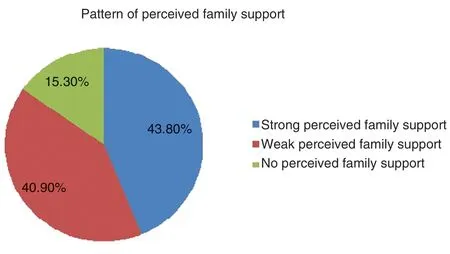

Of the 313 T2DM patients for whom data were analyzed,43.8% (137) had strong perceived family support, 40.9% (128)had weak perceived family support, and 15.3% (48) had no perceived family support ( Fig. 1).

Figure 2 shows the level of glycemic control among the participants. Most of them had poor glycemic control (186,59.7%), while 40.6% (127) had good glycemic control.

Table 1. Sociodemographic characteristics of the respondents

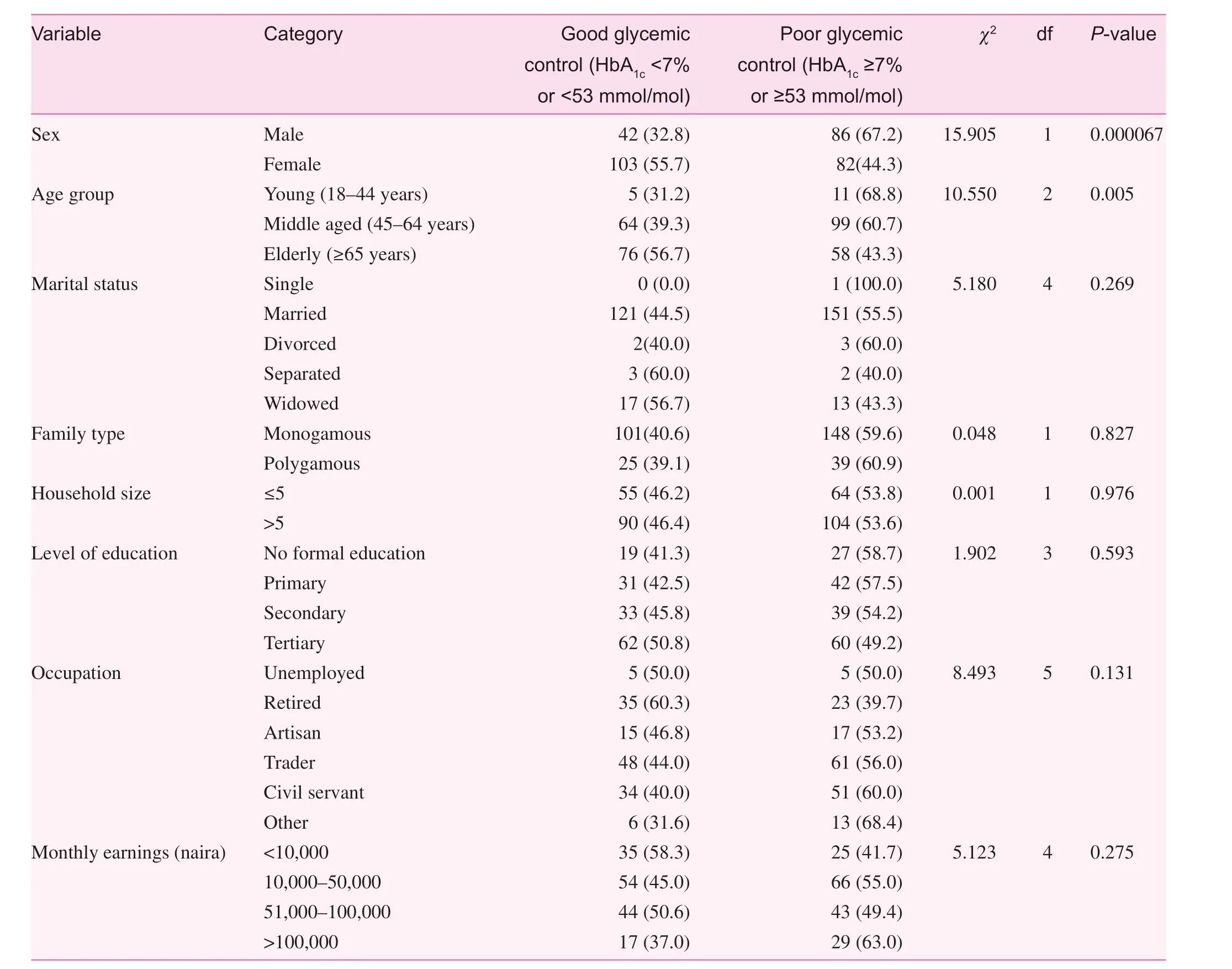

Bivariate analysis of the association of sociodemographic factors with glycemic control showed that age( χ2= 10.550, P = 0.005) and sex ( χ2= 15.905, P = 0.000067)were statistically signif icantly associated with glycemic control ( Table 2).

Fig. 1. Pie chart showing the pattern of perceived family support among the respondents.

Fig. 2. Pie chart showing the pattern of glycemic control among the respondents.

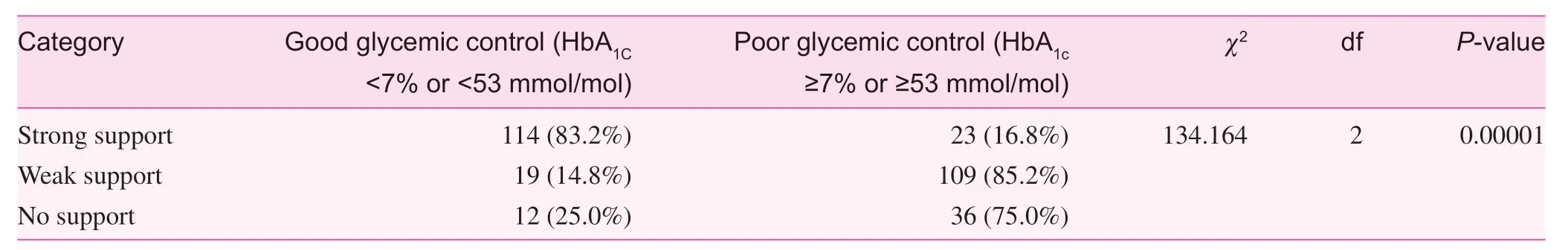

Perceived family support was also signif icantly associated with glycemic control ( χ2= 134.164, P = 0.00001) ( Table 3).The independent predictor of glycemic control in this studywas strong perceived family support ( P = 0.00001, OR = 112.51,95% CI = 46.638— 271.440) ( Table 4).

Table 2. Relationship between glycemic control and sociodemographic factors

Discussion

The age distribution depicted by this study with more than 90%of the respondents in the middle-aged and elderly age groups typif ies the age of patients with T2DM seen in Nigeria. Old age is a universally recognized risk factor for the development of DM and other chronic diseases [ 1, 8, 20, 21]. In the typical patient with T2DM seen in Nigeria, T2DM is diagnosed in the f ifth to sixth decade of life [ 8, 20, 21]. This f inding underscores the importance of health promotion through lifestyle changes and screening programs for Nigerians who are aged 40 years or older.

About 59.4% of the participants had poor glycemic control. Available local and international literature on the level of glycemic control among T2DM patients also revealed poor glycemic control [ 2— 4, 8, 20— 23]. The largest multicenterdescriptive cross-sectional study (2352 T2DM patients)conducted in six sub-Saharan African countries to study the quality of glycemic control and coexisting DM-related complications (the Diabetes Africa Study) reported good glycemic control in only 29.0% of the study participants [ 23]. Similarly,in a multicenter study that involved seven tertiary hospitals across the six geopolitical zones in the country (Diabetic Care Nigeria Study), less than one-third of patients studied attained the guideline-recommended glycemic targets of a hemoglobin A1clevel less than 7.0% and a mean hemoglobin A1cvalue of(8.3 ± 2.2)% [ 3, 21].

Table 3. Relationship between glycemic control and perceived family support of the respondents

Table 4. Logistic regression analysis of signif icant factors associated with glycemic control

In general, the low rate of optimal glycemic control among DM patients has been attributed to poor adherence to antidiabetic medications and f inancial constraints [ 3, 21, 24]. Poor adherence in a resource-poor country such as Nigeria may be due to poverty. Thus, f inancial constraints may be a key factor responsible for poor glycemic outcome seen in Nigeria. In addition, the small percentage of Nigerians with DM (less than 10.0%) who are members of the National Health Insurance Scheme or any other insurance scheme makes patients bear the cost of care at a price that is much higher than the cost of these services in other parts of the world [ 3, 21]. Thus, support from family members may assist in relieving DM patients of the huge f inancial burden of care.

This study showed that older patients had better glycemic control than younger patients. Achievement of glycemic control among patients older than 65 years was greater than that among the other age groups. This is consistent with the f indings of other studies [ 25, 26]. The US National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2007— 2010 reported that glycemic control was best among those aged 65 years or older and worst among those aged 18— 39 years [ 26]. Ahmad et al.[ 25] reported that an increase in age of 1 year was associated with a 3% increase in the likelihood of achieving targeted glycemic control. Being elderly may attract support from family members in terms of elderly people being reminded of their medications, clinic attendance, and lifestyle. This might play a role in increasing adherence in elderly people, and thus could have contributed to the better glycemic control among them.

Contrary to the f inding in this study, Ewenighi et al. [ 27] in a study conducted in Edo state, Nigeria, reported that younger people with T2DM are more likely to have better glycemic control than elderly people. The difference between the f inding in this study and the Edo study could be attributed to the study design. The Edo study was an interventional study where the study participants were subjected to the same 20-week glycemic control therapy involving oral medication (metformin)and lifestyle intervention (diet), which ultimately reduced the issue of nonadherence [ 27].

The f inding of more females achieving good glycemic control than males in this study is in keeping with the f indings of most studies that investigated the inf luence of sex on glycemic control [ 28, 29]. Many factors may have contributed to this observation. Firstly, the likelihood of being screened for DM is higher in women than in men because of more contact with health facilities during the reproductive years. Secondly,women are more inclined to have better health-seeking behavior, adhere to regular follow-up, and have a more adaptive attitude toward DM [ 30]. However, better glycemic control in males has been reported. This is especially from a study done in an area where the socioeconomic status of women is poor[ 31]. Considering the inconsistent f indings on the inf luence of sex on glycemic control, interventional approaches should go beyond sex differences in glycemic control. They should be focused on improving patients’ and family members’ understanding of the disease.

Although the traditional African family structure is gradually being eroded as a result of urbanization [ 32], the f inding of more than two-f ifths of respondents having strong perceived family support and less than one-f ifth of respondents having no perceived family support agrees with the fact that Africans have a naturally rich social support network [ 33]. This result is comparable to the f indings in southwest Nigeria of Adetunji et al. [ 8], who reported that 49% of the people with T2DM studied had strong perception of family support. The strong family and kinship ties as expressed in daily life and interactions that are inherent in African culture may explain the high rate of strong perceived family support seen in this study. The great number of married and elderly respondents in the study may also be responsible for the high level of strong perceived family support in this study. It is known that married and older people are more likely to report better perception of family support than younger people [ 8, 34, 35].

This study showed that strong perceived family support is an independent predictor of good glycemic control and that respondents with strong perceived family support were approximately 112 times more likely to have good glycemic control than respondents without strong perceived family support (OR = 112.51, 95% CI = 46.638— 271.440). There is a lack of agreement in the literature on the effect of perceived family support on glycemic control in DM patients. Generally, most studies reported better self-care behavior among DM patients with strong family support without corresponding improvement in glycemic control [ 36, 37]. A systematic study also showed that health outcomes in patients with uncontrolled glycemia can be improved only when family support is integrated with DM self-management [ 38].

The variation in the relationship between family support and health outcomes in DM may be due to the varying family pattern norms in different parts of the world. While this study and other African studies [ 7, 8, 20] showed a positive relationship between family support and glycemic control, studies done outside Africa showed no specif ic direction [ 36, 37, 39].A typical African family has been described to be mostly rural,polygamous, and open to kinship networks [ 40]. The naturally rich social networks seen in Africans may explain the positive inf luence of family support on glycemic control among Africans.

The present study has contributed to the evidence on the positive inf luence of perceived family support on glycemic control among African T2DM patients. In the face of the evolving changes in sub-Saharan African family structure due to modernization, the family still remains an important tie in the social life of Africans. The belief in collectivism, as opposed to individuality that is entrenched in the traditional African family system, ensures that patients with chronic diseases such as DM receive support from their family and friends.

Family support is important in the long-term management of DM, which requires a lifelong change in the lifestyle of the affected person. Strong perceived family support will improve their self-worth and motivation. It is plausible that a motivated person with DM will adhere to therapeutic plans and therefore achieve better glycemic control. It is essential that health care providers involve families of people with DM in their management so as to improve patients’ function and treatment outcome. More importantly, physicians should use an integrated approach that incorporates family engagement into T2DM self-management models. Future research in this area should include randomized controlled trials on the inf luence of family support on self-care behavior and glycemic control among people with T2DM.

The following limitations were considered in this study.Firstly, this was a hospital-based study, and thus the results may not be generalizable to all people with DM. Secondly, as a result of the cross-sectional design of this study, the f indings from it cannot address issues of causal relationships between glycemic control and the factors found to be associated with it.The study relied on a questionnaire to elicit information from the respondents. The responses could be subjective and may not ref lect the actual perception of family support.

Conclusion

This study showed that sex, age group, and perceived family support were signif icantly associated with glycemic control.Among the three variables that were associated with glycemic control, strong perceived family support was the only independent predictor of good glycemic control among people with T2DM. This study implies that the perception of family support may be of value to African patients with T2DM in achieving optimal glycemic control. Physicians working in sub-Saharan African countries with rich kinship networks should harness the available family support of people with T2DM in their management.

Acknowledgments

We especially thank all our colleagues in the Department of Family Medicine for their contributions during the preparation of this work.

Conf lict of interest

The authors declare no conf lict of interest.

Funding

Financing of the project was borne by the researchers. There were no direct or indirect monetary costs for the study participants.

Author contributions

Nnenna Angelina Osuji, Oluwaseun Solomon Ojo Peter Taiwo Sogunle, and Olukayode Sunday Malomo conceptualized the study. Nnena Angelina Osuji, Oluwaseun Solomon Ojo,Sunday Olukayode Malomo, Peter Taiwo Sogunle, Ademola Oluwaseun Egunjobi, and Oluf isayo Oyewe Odebunmi designed the research. Nnena Angelina Osuji, Oluwaseun Solomon Ojo, Sunday Olukayode Malomo, Peter Taiwo Sogunle, Ademola Oluwaseun Egunjobi, and Oluf isayo Oyewe Odebunmi collected and analyzed the data. Nnena Angelina Osuji, Oluwaseun Solomon Ojo, Sunday Olukayode Malomo, Taiwo Peter Sogunle, Ademola Oluwaseun Egunjobi and Oluf isayo Oyewe Odebunmi wrote the paper. Nnenna Angelina Osuji, Oluwaseun Solomon Ojo, Sunday Olukayode Malomo, Peter Taiwo Sogunle, Ademola Oluwaseun Egunjobi,and Oluf isayo Oyewe Odebunmi edited the paper. All authors read and approved the f inal article.

Family Medicine and Community Health2018年4期

Family Medicine and Community Health2018年4期

- Family Medicine and Community Health的其它文章

- Adherence to clinical guidelines for monitoring diabetes in primary care settings

- Predictors of successfully quitting smoking among smokers registered at the quit smoking clinic at a public hospital in northeastern Malaysia

- Nutritional status in adolescent girls: Atte mpt to determine its prevalence and its association with sociodemographic variables

- Factors associated with visit-to-visit variability of blood pressure in hypertensive patients at a Primary Health Care Service, Tabanan,Bali, Indonesia

- Effi ciency of community health centers in China during 2013– 2015:A synchronic and diachronic study*

- Comprehensive AIDS prevention programs in prisons: A review study