Adherence to clinical guidelines for monitoring diabetes in primary care settings

Mingliang Dai , Michael R. Peabody , Lars E. Peterson , Arch G. Mainous III

1. American Board of Family Medicine, 1648 McGrathiana Parkway, Suite 550, Lexington,KY 40511, USA

2. University of Florida, Department of Health Services Research, Management and Policy,1225 Center Drive, HPNP 3107,Gainesville, FL 32611, USA

3. University of Florida, Department of Community Health and Family Medicine, 1225 Center Drive, HPNP 3107, Gainesville,FL 32611, USA

Abstract Objective: Adherence to clinical guidelines is key to improving diabetes care. Contemporary knowledge of guideline adherence is lacking. This study sought to produce a national snapshot of primary care physicians’ (PCPs) adherence to the American Diabetes Association guidelines for monitoring diabetes and determine whether continuity of care promotes adherence.Methods: Using the 2013 National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey, we examined adherence to ordering hemoglobin A 1c (HbA 1c) and lipid prof ile tests as recommended by the American Diabetes Association for monitoring diabetes in 2379 primary care visits of patient with diabetes.Results: In the preceding 12 months, less than 60.0% of the patients were given a test recommended for monitoring diabetes (58.0% for HbA 1c and 57.0% for lipid prof ile). Continuity of care with PCPs increased the odds of adhering to diabetes monitoring guidelines by 36.0% for the HbA 1c test ( P = 0.06) and by 76.0% for the lipid prof ile test ( P = 0.0006).Conclusion: A substantial gap exists in achieving optimal monitoring for diabetes in primary care settings in the United States. While PCPs are ideally positioned to ensure that guidelines are closely followed, we found that even in primary care settings, patient-provider continuity of care was associated with guideline adherence.

Keywords: Diabetes; guideline adherence; primary care; continuity of care

Introduction

Diabetes affects more than one in ten adult Americans aged 20 years or older, and its prevalence has increased dramatically over the past two decades and continues to grow disproportionally among Hispanics and non-Hispanic blacks [ 1— 4]. Despite being one of the leading causes of hospitalization in the United States[ 5], acute and chronic complications of diabetes may be prevented or mitigated with evidence-based therapeutic treatments [ 6, 7].

Ensuring appropriate quality of care is key to effective management of diabetes. The National Committee for Quality Assurance’ s Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS)measures important dimensions of care and services for diabetes that are used by more than 90.0% of US health plans [ 8].The diabetes quality measures follow the clinical guidelines issued by the American Diabetes Association (ADA) [ 9]. Yet the outcomes of controlling diabetes have been less than optimal. Of the patients receiving diabetic medications, 40.0% did not have their diabetes under control [ 10]. More specif ically,only 29.0%— 57.0% of patients reached their goal for glycemic control and 31.0%— 46.0% for lipid targets [ 11— 13]. To remedy this def iciency, considerable research has demonstrated that quality improvement strategies are effective in improving clinical outcomes (e.g., glycemic control or reducing hemoglobin A1c[HbA1c] values) [ 14— 18].

In contrast to the national effort to achieve better treatment goals, contemporary knowledge of physicians’ adherence to process measures (e.g., ordering regular HbA1cand lipid prof ile tests), which is equally important for successful longterm diabetes management, is lacking. Studies from 20 years ago found very poor adherence to ADA standards, with only 15.0%— 20.0% of diabetic patients receiving recommended tests [ 19, 20]. Despite increasing attention to quality of care since then, in 2010 only one in four adults aged 40 years or older received recommended tests [ 21]. In comparison, adherence to guidelines in European countries was much higher,ranging from 65.0% to 85.0% for HbA1ctests and from 67.0%to 89.0% for annual lipid prof ile tests [ 22— 24].

Improving the quality of care for patients with diabetes is crucial in relieving both the disease burden on the patients and the economic burden on society [ 25]. Given that most patients with diabetes are cared for in primary care settings [ 26— 29], it is important to assess adherence to diabetes monitoring guidelines among primary care physicians (PCPs). Gaps in adherence will alert physicians to missed opportunities that may help achieve optimal long-term care for patients with diabetes.

Moreover, adherence to guidelines needs to be examined in the context of patient-provider continuity relationships,which is a core principle of primary care. A handful of studies that directly assessed the role of patient-provider continuity reported inconsistent results. Patients with diabetes who indicated a usual source of care were signif icantly more likely receive a diagnosis and have better glycemic control [ 23, 30].However, the likelihood of receiving HbA1cand lipid prof ile tests was not statistically different regardless of the level of continuity [ 31]. These f indings, while insightful, were ref lective of diabetes care in the 1990s. Research built on current patient encounters is needed to determine the effect of continuity in today’ s changing primary care settings. This study sought to produce a contemporary national snapshot of PCPs’adherence to diabetes monitoring guidelines and to determine whether continuity of care promotes adherence.

Methods

Data

We used the 2013 National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey(NAMCS) public use f ile to draw a nationally representative sample of primary care visits of patients with diabetes. The NAMCS is a national probability sample survey of patient visits to off ice-based physicians conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics [ 32]. The sampling frame for the 2013 NAMCS was composed of all physicians whose names are contained in the American Medical Association and the American Osteopathic Association master f iles who were off ice based, principally engaged in patient care activities, not federally employed, not in specialties of anesthesiology, pathology, and radiology, and younger than 85 years at the time of the survey. The 2013 NAMCS included 11,212 physicians:10,595 doctors of medicine and 617 doctors of osteopathy. Of the 6999 remaining eligible physicians, 2705 participated in the survey, and data were collected for 54,873 patient visits [ 33].

Sample

We started with the full sample of 54,873 patient visits in the 2013 NAMCS and applied two sample selection criteria to create the analytical sample. First, we excluded 40,113 visits that were made to non-PCPs, leaving us with 14,760 visits made to PCPs, who we def ined as general practitioners, family physicians, and general internists. Second, we excluded 12,381 visits of nondiabetic patients on the basis of both diagnoses and reports by physicians that were used to identify patients with diabetes. An individual was determined to have diabetes if the primary, secondary, or tertiary diagnosis code was in the range of 250.xx, or if the physician indicated that the patient had diabetes regardless of the diagnoses previously entered.Our analytical sample included 2379 primary care visits of patients with diabetes.

Measures

We examined guideline adherence for two common laboratory tests recommended for monitoring diabetes: the HbA1ctest and the lipid prof ile test. We used the 2013 ADA guidelines as the benchmark for adherence. On the basis of expert consensus and clinical experience, the 2013 ADA guidelines recommended that physicians order (1) the HbA1ctest twice a year for patients with stable glycemic control and more frequently for those not meeting the goals and (2) the lipid prof ile test at least annually [ 9]. As these recommendations are consistent with the preceding ones released in 2012, 2011, and 2010 [ 34— 36], it would be reasonable to expect that clinicians’practice in 2013 reliably ref lected their adherence to these guidelines. Since the number of tests ordered was not available in the NAMCS, we analyzed responses (yes/no) to the following question: “ Was blood for the following laboratory tests drawn on the day of the visit or during the 12 months prior to the visit?” For the HbA1ctest, adherence to guidelines was achieved if the response was “ Yes.” Admittedly, this def inition was more lenient than the ADA guidelines, and may overestimate adherence. For the lipid prof ile test, which usually consists of tests for total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein, low-density lipoprotein, and triglycerides, adherence to guidelines was achieved only if all four tests were conducted.Continuity of care was measured by responses (yes/no) to the following question: “ Are you the patient’ s primary care physician?” Patients were considered to have continuity of care if they were seen by their PCP. We also used the responses to distinguish patients who were seen by their PCPs from others who were seen by non-PCPs. We measured patients’ age (as a continuous variable), sex, and race/ethnicity. The NAMCS coded a maximum of three provider’ s diagnoses in sequence according to the International Classif ication of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modif ication, which we mapped to the Charlson comorbidity index [ 37] to calculate a comorbidity count for each patient.

Statistical analysis

We used the demographic and comorbidity prof ile of the patients to characterize primary care visits of patients with diabetes in 2013. The percentage of patients who received a HbA1ctest or a lipid prof ile test in the preceding 12 months was calculated as an indicator of the degree to which physicians adhered to the guidelines. Pearson’ s chi-square tests were conducted for both HbA1cand lipid prof ile tests to examine whether PCPs more closely adhered to the guidelines than non-PCPs. The impact of continuity of care on achieving adherence for each test was estimated in logistic regression models with adjustment for patients’ age, sex, race/ethnicity,and comorbidity count, and whether they were seen by their PCP. Visit weight and sampling strata variables were included in all the analyses to account for the 2013 NAMCS’ s design and sampling schemes and also to generate nationally representative estimates. All statistical analyses were conducted in SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, United States).

Results

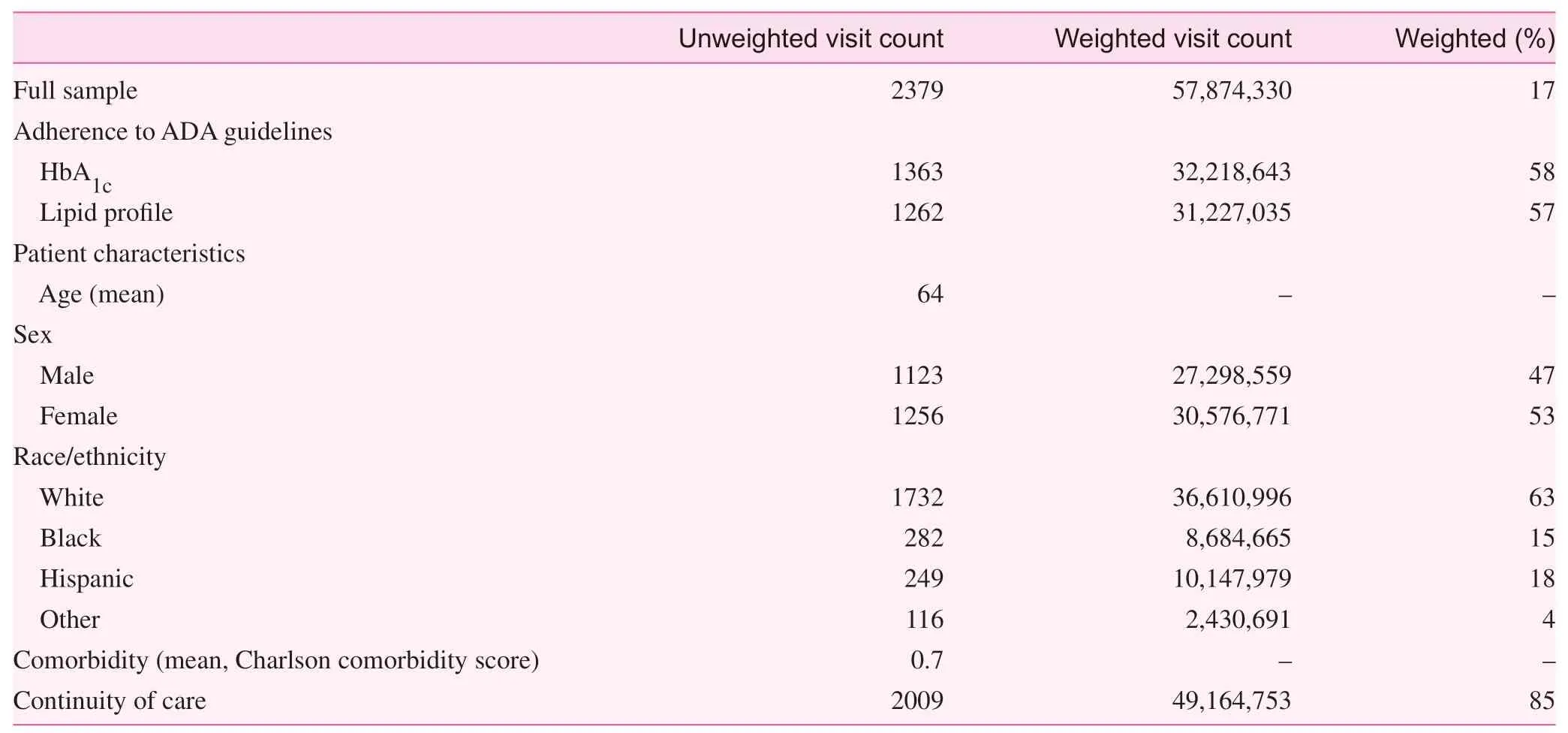

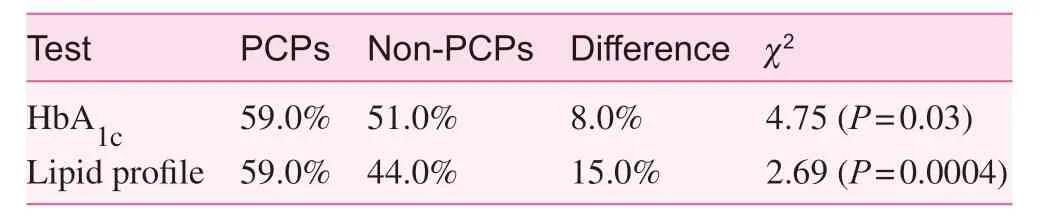

In 2013, 17.0% of the primary care visits involved patients with diabetes, representing a total of 57 million visits( Table 1). Most patients in these visits were male, white,and non-Hispanic, with a mean age of 64 years and with few comorbidities except for diabetes. Patients were seen by PCPs in eight out of ten visits. Less than 60.0% of the patients with diabetes received recommended monitoring for diabetes (58.0% for HbA1cand 57.0% for lipid prof ile) during the preceding 12 months. PCPs ordered recommended tests more often than non-PCPs: 59.0% vs. 51.0%, respectively,for the HbA1ctest ( χ2= 4.75, P = 0.03) and 59.0% vs. 44.0%,respectively, for the lipid prof ile test ( χ2= 12.69, P = 0.0004);see Table 2.

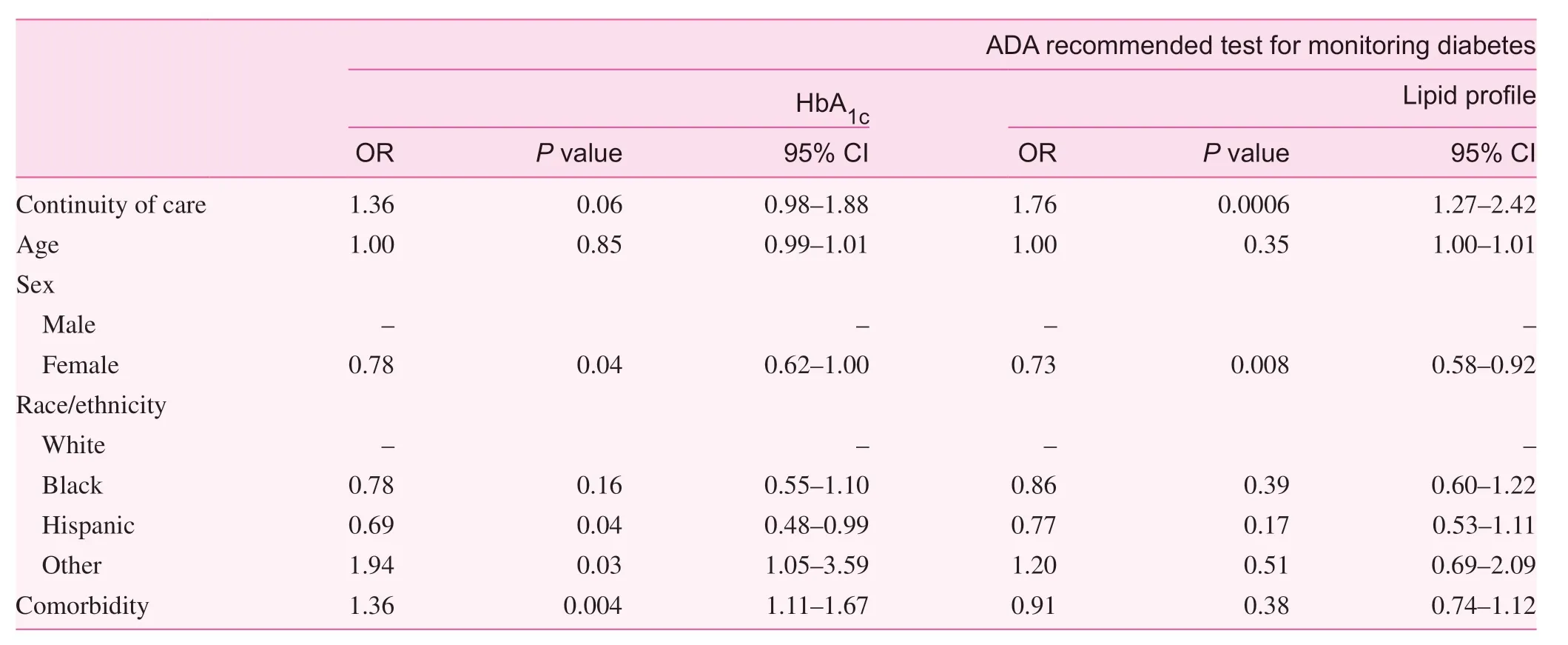

After we had accounted for patient characteristics, continuity of care was associated with improved guideline adherence ( Table 3). Continuity of care was associated with increased odds of physicians adhering to guidelines for the HbA1ctest (odds ratio 1.36, 95.0% conf idence interval 0.98— 1.88, P = 0.06), but not signif icantly, and for the lipid prof ile test (odds ratio 1.76, 95.0% conf idence interval 1.27— 2.42, P = 0.0006). Hispanic and female patients had signif icantly lower odds of receiving the HbA1ctest and the lipid prof ile test, respectively. More comorbidities were associated with higher odds of receiving the HbA1ctest but not the lipid prof ile test.

Table 1. Characteristics of primary care visits of patients with diabetes in 2013 in the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey

Table 2. Weighted difference in ordering diabetes monitoring tests between primary care providers (PCPs) and non-PCPs

Discussion

Diabetes is one of the f ive most common chronic diseases in the world and has substantial implications for the health and economic well-being of individuals, families, and nations[ 38]. Adherence to clinical guidelines by PCPs is key to effectively managing and preventing complications for those with diabetes, and is potentially more so for early detection and prevention of the condition for those at risk [ 39, 40].

Despite the widespread dissemination of clinical guidelines to both health care providers and patients [ 41], we found that PCPs’ adherence to the ADA guidelines for monitoring diabetes was less than optimal in a nationally representative sample of primary care visits of patients with diabetes. While the proportion of patients receiving recommended tests in 2013 was much higher than in 2010 [ 21], there were still 40.0% of visits where patients with diabetes had not received any monitoring test in the preceding 12 months. This reveals a substantial gap between what was done in primary care settings and what is recommended for optimal diabetes management. It is worth noting that the estimates of physicians’adherence to diabetes guidelines derived from the NAMCS are lower than those from HEDIS measures [ 42], probably due to substantial differences in the sampling frame. For example, the HEDIS measure of HbA1ctesting was calculated with all eligible patient encounters over the calendar year,while the NAMCS measure was based on PCPs’ self-report of ambulatory visits in a random week with a retrospective timeframe of the 12 months before the visit. Without regularly monitoring glycemic and cholesterol levels, PCPs are unable to intensify treatment to prevent complications. Adhering to the guidelines for monitoring diabetes enables PCPs to make more timely decisions that are both clinically meaningful and cost-effective.

The current f indings support the positive effect of continuity of care on diabetes quality of care [ 43]. Compared with prior studies that found no association between provider continuityand diabetes care, the continuity measure derived from the NAMCS was provider specif ic and based on provider self-identif ication as opposed to indexes that calculate a continuity score accounting for all providers of the patient or measures drawn from patient self-report [ 30, 31]. While answers to all of the identif ied challenges to adherence and implementation of guidelines for diabetes care are beyond the scope of this study, we found that continuity of care, a core tenet of primary care, increased the odds of adhering to guidelines, after patient characteristics had been controlled for [ 44— 47]. These results reinforce the importance of the patient-provider relationship in management of a chronic disease. Last but not least, efforts to improve guideline adherence may yield larger benef its for Hispanic patients,who of all the race/ethnicity groups were the least likely to have been given a HbA1ctest in the preceding 12 months, and among whom the prevalence of diabetes is still rising [ 1].

Table 3. Association of continuity of care and adherence to guidelines for monitoring diabetes.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, we were unable to measure the number of HbA1ctests that were given in the preceding 12 months. Our def inition of adherence for the HbA1ctest was more lenient than the ADA guidelines, which essentially lowered the threshold of being adherent. As a result,the 40.0% nonadherence rate might be an underestimate.Second, also because of the unavailability of test counts, we were unable to determine whether overordering was an issue in nearly 60.0% of the visits where patients did receive HbA1ctests [ 48]. Third, responses in the NAMCS about whether tests were ordered for the patient in the preceding 12 months may be subject to recall bias. Last, our assessment of continuity of care was conf ined to interpersonal continuity. Future studies are encouraged to examine the inf luence of informational or administrative continuity on guideline adherence [ 49].

Conclusions

Forty percent of primary care visits of patients with diabetes were missed opportunities where PCPs were not providing guideline-concordant monitoring tests, creating a substantial gap in the quality of care for diabetes in US primary care settings. Improving guideline-concordant disease monitoring in diabetes in primary care was highlighted by the World Health Organization to reduce the impact of diabetes worldwide [ 50]. Our f indings suggest that enhancing patientprovider continuity of care may be effective in promoting guideline adherence.

Conf lict of interest

The authors have no conf lict of interest.

Funding

The American Board of Family Medicine Foundation supported Dr. Mainous.

Family Medicine and Community Health2018年4期

Family Medicine and Community Health2018年4期

- Family Medicine and Community Health的其它文章

- Relationship between glycemic control and perceived family support among people with type 2 diabetes mellitus seen in a rich kinship network in Southwest Nigeria

- Predictors of successfully quitting smoking among smokers registered at the quit smoking clinic at a public hospital in northeastern Malaysia

- Nutritional status in adolescent girls: Atte mpt to determine its prevalence and its association with sociodemographic variables

- Factors associated with visit-to-visit variability of blood pressure in hypertensive patients at a Primary Health Care Service, Tabanan,Bali, Indonesia

- Effi ciency of community health centers in China during 2013– 2015:A synchronic and diachronic study*

- Comprehensive AIDS prevention programs in prisons: A review study