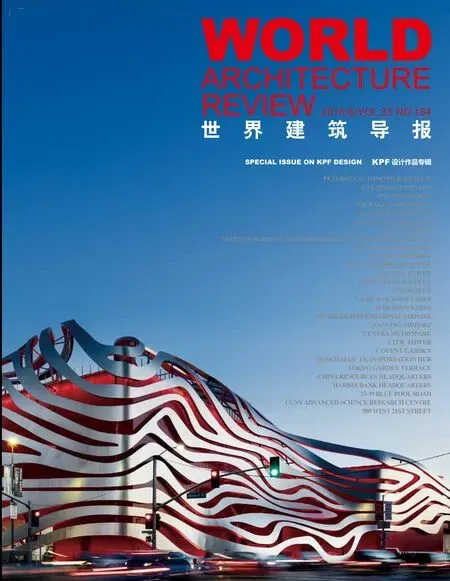

关于工艺

by James von Klemperer

在建筑实践中,KPF建筑事务所一直坚信无论一项设计理念如何雄心勃勃,只有当其创建者以谨慎的思维和严谨的态度在项目后期实现其设计目的后才算成功。因此,只有伟大的创意是无意义的,除非其衍生出可支撑其起始论点的材料和细节。

在当代大型建筑中,建筑项目往往面临着理论目的和物理实现间的差距,且此差距正变得越来越大。进度、预算和物流管理上的超常的严谨性带来了设计和施工间的分工。在传统意义上,建筑师具有更广的角色定位,即“全专业负责人”和“建筑监督和检查员”,而这一定位已经让位于劳动分工。个体可以多年专注于像楼梯细节或钢结构施工图纸之类的单一任务。

但我们可设想一下,对于更具综合性或整体性的建筑应该怎样去实现呢?KPF的建筑师们强调保持设计概念和施工完成之间的连续性,将其放在优先位置。个体在团队中发挥作用,团队负责建筑项目的整体展开,即从方案图纸设计到建筑投入使用。在整个过程中,“工艺”的概念将设计与实现进行连接,突出生产技术的优点。传统砌砖模式、木工细工逻辑及新型材料的现代工艺都影响着建筑理念。若要了解设计和建造之间的关系,我们可以看一下建筑师的角色(作为设计师、制造者和建造者)是怎样随时间演变的。避开对卷帙浩繁的建筑历史的深入调查,我们可以看一下整个建筑史上的几个关键时期和重要人物。

从十五世纪的意大利开始,透视绘图让建筑师拥有了空间构思的新型工具,其中Fillippo Brunelleschi在某种程度上代表着理想化的“总建筑师”。虽然他最著名的是设计了佛罗伦萨的Duomo大教堂,但他职业生涯的起点是工匠。尽管他为洗礼堂铜门设计的作品输给了Lorenzo Ghiberti,但紧接着他便成功承接了教堂穹顶的设计任务。他的金属工匠的技能也影响到了建筑作品的设计。

作为Duomo大教堂的建筑师,Brunelleschi对其每一建筑细节都进行了深思。不仅设计了教堂的压缩抛物线结构和链形张力环,还为其设计了脚手架及可运升砌体的新结构系统。基于对生产力的了解,他甚至对工人吃饭喝水的地点和时间也做了安排。他在这些角色上取得的成功让这一建筑项目实现了非凡的工程成就,也让他成为了现在的文艺复兴代表人物。

Fillippo Brunelleschi为理念与实践的融合做出了很好的示范,他是早期“总建筑师”的典范,但在后来的实践中却一直在两者的“融合”和“分裂”间来回摇摆。需要注意的是,随着多次工业革命的发生,机械化逐渐增强,这对人文主义的方法原则提出了挑战。

从十九世纪初开始,越来越多的欧洲工厂建立了生产效率新标准。随着此类工程和工业的进步和发展,形成了新的社会秩序,也带来了巨大的机遇和挑战。工艺和机械之间的固有冲突形成了建筑理论家和实践者所面对的根本问题。

John Ruskin、A.W.N. Pugin和William Morris等理论家领导了英国手工艺运动,批判了工业时代与传统工艺的脱节。他们赞扬由建筑师最大程度上参与设计的本土物质文化。理想的“工匠-设计师”可将装饰织物、家具和灯光的设计与制备工艺结合起来,努力营造出一个更有意义的生活环境。

二十世纪初期,几位德国哲学家和德意志工艺联盟成员提出设计应当在工业过程中拥有自己的角色。AEG涡轮机厂(1909)便是历史上的一个重要例子,它表明工业可以同时具有趣味性和美感。AEG灯泡等很多工业设计也成为此手工艺运动的最好说明。在此之后,包豪斯建筑学派对艺术与工业的此类结合所产生的部分伟大成果进行了概括。此学派的创始人兼名誉领袖Walter Gropius对以建筑作为主要学课的总体艺术或“整体艺术”进行了赞扬。被描述为轮状图表的包豪斯课程和课程作业,融合了绘画等形式研究领域,同时也对材料和建筑科学进行了探索。这种工艺方法影响了当时的很多著名的建筑,强化了建筑行业的现代化概念。

在哈佛大学工作的Gropius不仅设计了其宿舍,还设计了宿舍中的椅子、地毯和灯具。他推崇这种方法,并在课堂上强调建筑师应对影响日常生活的所有物品进行考虑,展现他们的劳动成果。同时,现代建筑对抽象的偏好也继续引起许多负面反应。严肃的棱角空间通常更强调效率和秩序感,而不是舒适性和熟悉感。法国电影制片人Jacques Tati在《玩乐时间》(1967年)中叙述了一个关于失落主人公的警世故事,这位主人公被淹没在高楼大厦和狭窄隔间的海洋中,试图在一个没有人情味的现代世界中存活下来。在建筑行业中一直存在着这样的拉锯,上个世纪积累下的现代建筑便是最好的证明。

在当今的中国,我们也遭遇了类似的辨证逻辑。直到20世纪30年代,中国的很多岌岌可危的历史建筑也没有得到足够的重视。很多重要的历史遗迹被遗弃,默默凋零。梁思成和林徽因改变了这种状态,开始对此类结构进行记录,并倡导对它们进行保护。在美国学完艺术和建筑后,回到北京,他们作为世俗知识分子的典范,本可以对传统进行批评或甚至直接拒绝传统。但是在现代化元素越来越多的时代中,他们作为设计师捍卫了传统建筑的内在价值,特别是木构寺庙建筑。他们的征程和记录工作至今依然鼓舞人心。

这些案例提醒我们思考我们为什么学习和实践建筑学。我们的工作是理解特定的物理和文化背景基因,并将这些基因与整体设计相融合。例如,KPF在上海新天地设计的安达仕酒店和朗廷酒店。正面是具有历史意义的城市景观,而从背面看,两栋建筑的石材外立面则让人想起传统的屏风。设计充分考虑体量、材料和环境的相互作用,打造引人入胜的视觉对话,有助于邻里空间的城市场所营造。

KPF尽可能的充分利用各种材料,包括陶土、石材、玻璃、金属和木材,用现代工艺重新诠释传统做法。在各项目中,KPF进行了深入多样的材料研究和探索,包括香港蓝塘道住宅项目中人居尺度上的工艺青铜门细节以及纽约范德比尔特一号项目塔楼外立面带有凹槽的陶土层间板。

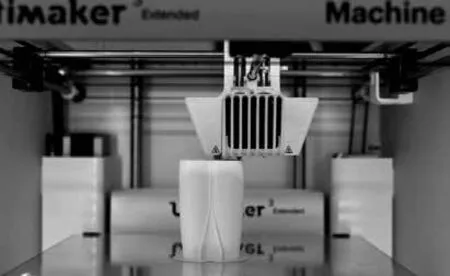

KPF对工艺的注重体现在事务所积极拥抱未来的工艺工法。计算机脚本设计、3D打印和数字建模已经将建筑推向了一个非凡的新时代,但我们作为建筑师的责任依然没有改变。数字化设计技术不仅可用于最大化采光、结构效率和功能可达性,也构成了一种赋予建筑美感和意义的新工艺。

计算机脚本设计可以帮助我们创建及实施建筑理念。在KPF,我们使用专有的算法脚本来拉近与工艺的距离,而不是与建造过程产生隔离。为了打造活力闪耀的立面,KPF团队应用了一套全新的数学系统,使用Grasshopper程序以最佳角度组合带涂层铝制单位组件,以提高反射率。纽约市杰克逊广场一号采用的如波浪般的竹制室内墙面如果没有对模型进行数字化操作和测试的能力,没有程序化数控加工技术控制精度,这项设计不可能实现。

我们对新技术的探索及应用始于我们的工作室。3D打印的兴起将材料、数字技术与设计相结合,使我们的设计师能够快速、精确地建立复杂的实体模型。基于包豪斯精神,我们认为,从部分纵观整体的设计洞察力以及遵循物理空间自然规则的设计能力对于建筑师与其作品之间的关系是至关重要的。

作为一家国际知名的公司,KPF打造的一些世界最高建筑和综合体项目得到广泛认可。项目成就通过许多人的共同努力得以实现。我们所运用方法的核心仍在于设计师与材料和施工方法的基本关系。展望未来,我们对公司提出的技术举措感到兴奋,例如公司组建了一支开发创新专有数字设计工具的内部团队,KPF城市界面团队(KPFui)。这项技术工具不仅有利于优化城市设计中的流动性、能效和其他效率,还可以实现城市体验中的亲密感。

KPF’s practice is rooted in the conviction that an ambitious design concept is successful only when its underlying intentions are thoughtfully and rigorously developed into the later stages of a project. Ultimately, a great idea is worthless unless it is embodied in materials and details that properly support its original thesis.

Too often, the execution of contemporary, large-scale architecture suffers from a widening gap between theoretical intention and physical realization. The formidable rigors of managing schedules, budgets, and logistics can result in a division of labor between design and construction, eliminating the traditional, broader role of the architect as “master of all trades” and “clerk of the works.” A given individual can work for years on such focused tasks as stair details or steel shop drawings. How then can we hope to further the goals of a more integrated or even holistic architecture?

At KPF, architects prioritize continuity between conception and completion.Individuals operate in teams responsible for the entirety of the project’s lifespan,from schematic drawings to the building’s opening. Throughout this process, the notion of “craft” links the design to its realization, making a virtue of the techniques of production. The patterns of traditional bricklaying, the logic of wood joinery, and the modern technologies of newly invented materials all inform the building concept.

To understand the relationship between designing and making, it helps to ask how the role of the architect — as designer, maker, and builder — has evolved over time.Without delving into an exhaustive survey of architectural history, it is worth considering a few significant moments and figures throughout the history of architecture.

Beginning in fifteenth century Italy, perspective drawing gave architects new tools with which to conceive of space, with Fillippo Brunelleschi representing a certain ideal of the “total architect.” Although he is most famous for designing the Duomo in Florence, he started his life as a craftsman. While his competition entry for the baptistery’s bronze doors lost out to Lorenzo Ghiberti’s, he followed by successfully securing the cathedral dome’s commission. His technical talents as a metalsmith informed his work at the scale of architecture.

As the Duomo’s architect, Brunelleschi thought about every piece of its complex puzzle. He designed not only its structure of compressive parabolas and chain tension rings, but also its scaffolding and a new system for hoisting masonry up the site. Based on his understanding productivity, he even prescribed what and when the workers should eat and drink. His success in such varied roles contributed to the project’s enormous engineering feats and gave him the stature of what we now call a Renaissance man.

Whereas Fillippo Brunelleschi provides us with an example of integrating the conceptual with the practical — an early example of the “total architect” — later periods experienced a continuous series of pendulum swings between “integrated”and “separated” practice. Notably, the increased mechanization that accompanied multiple industrial revolutions posed challenges to the tenets of a humanist approach.

From the early nineteenth century onwards, European factories established new standards of production efficiency. As advances in engineering and industry grew,new social orders arose, introducing tremendous opportunities and challenges. The inherent conflicts between craft and the machine raised fundamental questions for both theorists and practitioners of architecture.

Theorists such as John Ruskin, A.W.N. Pugin, and William Morris championed the English Arts & Crafts movement and critiqued the detachedness of the industrial age from traditional craftsmanship. They praised vernacular, material culture,made possible by the architect engaging in design to its fullest extent. The ideal“craftsman-designer” would link the design of fabric, furniture and lighting with the process of fabrication to make a more meaningful living environment.

In the early twentieth century, several German philosophers, and the members of the Deutscher Werkbund, proposed that design embrace its role in the industrial process. The AEG Turbine Factory (1909) is a prime historical example,demonstrating that industry could be at once interesting and beautiful. Examples of industrial design such as the AEG lightbulb illustrate this movement.

Later on, the Bauhaus epitomized some of the greatest outcomes of this marriage between art and industry. Walter Gropius, the school’s founder and historical figurehead,praised the total work of art — or “Gesamtkunstwerk”— for including architecture as a master discipline. The Bauhaus curriculum and coursework, depicted as a wheel-like diagram, incorporates formal studies such as painting while also exploring materials and building science. This approach to industrial craft influenced notable buildings of the day, reinforcing a modern notion of the architectural profession.

Working at Harvard University, Gropius not only designed the dormitory itself, but also its chairs, carpets and light fixtures. Emphasizing this approach, he taught that architects should consider every physical object that influences our daily lives,displaying the fruits of their labor. At the same time, modern architecture’s penchant for abstraction continued to evoke some negative reactions. Harsh, angular spaces often prioritized efficiency and order over comfort and familiarity. In Playtime (1967),French filmmaker Jacques Tati told a cautionary tale of a lost hero, engulfed in a sea of towering office buildings and tight cubicles, attempting to navigate a modern world devoid of human touch. This push and pull is ever-present in the profession,with a century of modern buildings serving as primary evidence.

In today’s China, we encounter similar dialectics. Until the 1930s, much of the country’s crumbling, historical architecture had not received significant attention.Many important monuments were abandoned and in disrepair. Liang Sicheng and Lin Huiyin altered that course, beginning to document such structures and advocate for their preservation. Having studied art and architecture in the United States then moving to Beijing, they were examples of the sort of worldly intellectuals who might critique or outright reject tradition. Yet as designers in an increasingly modern age,they defended the inherent value of ancient buildings, especially wooden temples.Their expeditions and efforts of documentation remain inspirational to this day.

Such examples remind us why we study and practice architecture. Our job is to understand and integrate the DNA of a given physical and cultural context into holistic design. For example, consider KPF’s design for the Andaz and Langham Hotels in the Xintiandi neighborhood of Shanghai. In the foreground, you see an historic cityscape.In the background, two stone facades evoke traditional screens. The design is an interplay of scale, material, and context. These relationships create a compelling visual dialogue and contribute to the neighborhood’s urban placemaking.

KPF strives to make use of a variety of materials such as terracotta, stone, glass,metal, and wood to reinterpret traditional methods with a contemporary hand. Our material exploration ranges from human-scale details in the artisanal bronze gates in the Blue Pool Road residences in Hong Kong, to the fluted terracotta spandrels that climb the towering facades of One Vanderbilt in New York City.

KPF’s focus on making exemplifies the way our studio has embraced the future of craft. Computer scripting, 3D printing, and digital modeling have propelled architecture into a remarkable new era, but as architects, our responsibilities are unchanged. Digital design techniques, which can be used to maximize daylight,structural efficiency, and functional accessibility can also constitute a kind of craft that imbues buildings with beauty and meaning.

Computer scripting can aid in the invention of architectural ideas and their execution.At KPF, we employ algorithms and proprietary scripts to bring us closer to our craft rather than isolating us from the building process. To create a dynamic, shimmering facade for Michael Kors, the KPF team used a novel mathematical system using the Grasshopper program to compose coated aluminum shingles at optimal angles for light reflectivity. The undulating bamboo interiors of One Jackson Square in New York City would not have been possible without the ability to manipulate and test a model digitally, and fabricated it through the precision of programmed CNC milling.

Our application of new technologies begins in the studio. Connecting material and digital craft, the rise of 3D printing has enabled our designers to create intricate physical models with speed and precision. Following in the spirit of the Bauhaus,we believe that understanding a design from the part to the whole and the ability to keep design grounded in the physical world is essential to the relationship between architects and their craft.

An international firm, KPF is most recognized for building some of the world’s tallest towers and complex mixed-use projects. Such feats of labor, engineering, and finance are achieved through the collaborative effort of many individuals. However,the core of our methodology remains rooted in the designer’s basic relationship to material and the methods of construction. Looking forward, we remain excited by technological initiatives at the firm such as KPF Urban Interface (KPFui), an internal team developing an innovative, proprietary set of digital design tools. This can result not only in the optimization of mobility, energy, and other efficiencies, it can also allow us to achieve an intimate sense of place in our urban experience.