The Contemporary Role of Femoral Artery Access

Syed Raza Shah, MD and Ki Park, MD

1UCF/HCA GME Consortium Internal Medicine, 6500 West Newberry Road, Gainesville, FL 32605, USA

2Division of Cardiovascular Medicine, University of Florida, 6500 West Newberry Road, Gainesville, FL 32605, USA

Abstract The scope of interventional cardiology has rapidly expanded over the last several decades. In a field where procedural treatment options for a variety of complex cardiovascular conditions have grown exponentially, the importance of procedural safety continues to come to the forefront. This is most evident in the movement toward radial access as the initial approach for operators in the cardiac catheterization laboratory. As the evidence grows for the superiority of radial access over femoral access with regard to reducing bleeding events and improving clinical outcomes, we discuss the modern approach to obtaining access, and highlight best practices.

Keywords: femoral artery; radial artery; interventional cardiology; cardiac catheterization

lntroduction

The field of cardiology has made tremendous progress over the last half century. In particular, the advent of cardiac catheterization by pioneers in the field such as F. Mason Sones Jr. and Melvin Judkins led the way for the ultimate uptake of angioplasty by Andreas Grüntzig in the late 1970s. As the field progressed, methods of arterial access have evolved as well. Sones initially pioneered vascular access via the brachial cut down method, which remained the initial standard with 8-Fr catheters throughout the 1960s. Judkins then introduced the femoral access technique through use of the Seldinger technique as well as development of preshaped diagnostic coronary catheters [1]. In the 1980s, lower-profile 6-Fr and 7-Fr catheters were introduced and, along with femoral access, became the standard. Initial attempts to promote the use of radial access in the 1990s were unsuccessful, primarily due to suboptimal equipment. It was not until the beginning to the middle of the first decade of this century that radial access gained prominence as lower-profile equipment and hydrophilic sheaths allowed operators to perform radial access more routinely and successfully while minimizing patient discomfort [2]. While a plethora of literature has shown radial access to be associated with lower bleeding risk, reduced rates of adverse outcomes, and high patient satisfaction, the role of femoral access in the contemporary field of diagnostic and interventional cardiac catheterization remains unclear. In this review we discuss the current state of femoral access in a “radial first” environment and highlight best practices for safe femoral access.

lmportance of Femoral Access

The abundance of data for improved safety outcomes with radial access is, at this point, difficult to deny. Multiple trials have demonstrated reduced bleeding outcomes and a signal toward reducing adverse clinical events [3, 4]. As many operators in the United States are converting to a primary radial approach, the role of continued femoral access is unclear. However, there will always be a subset of patients in which femoral access may be the only initial feasible option because of anatomy, vessel size, coronary anatomy, or other factors. Although the overall rates of radial-to-femoral conversion are low, evidence suggests that female sex, advanced age, and need for percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) predict the need for access site conversion [5]. Additionally, as the arena of structural interventions and hemodynamic support continues to grow, femoral access remains a critical component of these procedures. Despite advancements in technology that have dramatically decreased the size of contemporary sheaths, the need for femoral or other nonradial access is unlikely to change soon as the aforementioned structural and hemodynamic support devices cannot be performed via radial approach. As such, there will always be a role for femoral access. As the potential for bleeding complications is increased, a discussion of proficiency training and guidelines for best practices for femoral access is crucial to reducing risk in cases where femoral access is still used.

Complications Associated with Femoral Artery Access

Vascular access site complications, particularly bleeding, are some of the most feared complications after either diagnostic catheterization or PCI and are associated with increased morbidity and mortality [6]. Potential complications include relatively benign complications such as a superficial hematoma, but may also include arteriovenous fistula formation, development of pseudoaneurysm, vessel occlusion or perforation, and the severest – retroperitoneal bleeding. The latter can be indolent but deadly, especially in patients with other comorbidities compounded by potential underrecognition of early symptoms of bleeding. Additionally, certain populations may be particularly at risk, including women, the elderly, and those receiving antiplatelet or antithrombotic therapies. On the other hand,data collected from multiple studies have suggested that radial access is associated with fewer bleeding complications, is more cost-effective, and decreases hospital mortality rates compared with the femoral approach [7–11].

Components of Safe Femoral Artery Access

Accessing the femoral artery with minimal attempts is key in avoiding procedural complications. The use of fluoroscopy, ultrasonography, and femoral angiography during femoral artery access can help the operator obtain the proper arteriotomy position within the common femoral artery (CFA). Some of the measures used to decrease vascular access complications include use of micropuncture and avoidance of the use of arterial sheaths larger than 6 Fr as well as favoring 5-Fr sheaths for the initial diagnostic angiography. These techniques involve minimal change of equipment or procedure time but may contribute immensely to reducing femoral access site complications.

ldentifying Anatomy for ldeal Femoral Access

Different methods have been used to assist in localizing the CFA. Traditional landmarks based on the external position of the groin skin crease, palpation of the pelvic components, and so on are traditionally taught, although they can grossly misjudge the underlying CFA location, particularly in obese patients. Manual palpation of the artery can also be misleading as the presence of a high superficial femoral artery (SFA)–profunda bifurcation cannot be excluded, and palpation of a large SFA may cause the operator to believe the SFA is the CFA. If the patient has had a prior cardiac catheterization via the femoral approach, review of prior femoral angiograms can often be very helpful to provide guidance as to the most appropriate site for access.A radiodense object such as a metal clamp or hemostat is often used to estimate the location of the middle portion of the femoral head. Again, this does not necessarily exclude the location of the bifurcation. Some operators will access the CFA under direct fluoroscopy guidance, particularly if there is visible calcium in the vessel. However, this technique increases radiation exposure of the operator and does not account for CFA bifurcation anatomy.Femoral angiography should always be performed.This can be done either through the microsheath at the time of initial access (which is ideal as this allows removal, hemostasis, and repositioning of the access site) or at the completion of the procedure. Even if a closure device is not being considered, angiography is still helpful to guide staff in the proper manual compression technique and location.

Ultrasound Guidance

The exact location of CFA puncture is important in predicting outcomes. Ideally, the puncture is targeted toward the middle-third portion of the femoral head. This ideally will avoid puncturing at the SFA–profunda bifurcation and avoid too high an arteriotomy, which increases the risk of retroperitoneal bleed. Unfortunately, individual anatomy can differ,with some patients having a “high” bifurcation. As this anatomy cannot be evaluated by fluoroscopy,the use of ultrasound guidance has been promoted.The largest randomized controlled trial assessing the use of ultrasound guidance for femoral access,FAUST, studied ultrasound guidance in more than 1000 stable, nonacute coronary syndrome patients undergoing diagnostic catheterization and PCI if indicated. The primary comparison was between fluoroscopy guidance and ultrasound guidance and successful cannulation of the CFA. Overall, appropriate cannulation of the CFA was similar between groups; however, ultrasound guidance was superior in the setting of a high bifurcation [12]. Use of ultrasound guidance additionally was associated with reductions in the time to successful puncture,number of access attempts, and bleeding complications, primarily hematoma. However, the trial was not designed to assess clinical end points. Overall,adoption of ultrasound guidance for femoral access in the United States has remained low.

Needle Access/Sheath Placement

Traditionally, an 18-gauge needle was used to access the CFA. However, the smaller, 21-gauge needle (micropuncture technique) has become more widely used. The use of the smaller needle and associated microsheath allows removal of the needle or sheath with a smaller arteriotomy, allowing reattempted access with minimal trauma. Once blood return from the CFA is noted and an 0.018-in. wire has been positioned in the iliac artery,the position of the needle tip can be visualized under fluoroscopy, providing a general estimate of the arteriotomy position. Additionally, once the microsheath is in place before the 0.035-in. wire is advanced, a limited angiogram through the microsheath can be performed to confirm the appropriate arteriotomy position. Once the microwire has been exchanged for the 0.035-in. wire, the lowest-profile sheath for the intended study should be placed. This is somewhat dependent on the laboratory setup, but if a power injector is available, this is readily suited for 5-Fr diagnostic angiography. In the case of PCI,6 Fr should be chosen, when possible, over larger sheath sizes.

Access Site Closure

Multiple vascular closure devices (VCDs) exist to aid in obtaining femoral artery hemostasis. These devices are generally classified as extravascular or intravascular, with a mechanism of closure based on suture mechanisms or various plug-based devices.Closure devices can reduce the amount of downtime for patients, thus improving patient comfort as well as expediting work flow in the catheterization laboratory as “holding” time is reduced [13–15].Although a wide variety of closure devices are available, there is no guideline consensus on whether these devices reduce bleeding complications. The data for VCD use are limited and rely mostly on meta-analyses, which suggest that the use of a VCD does not necessarily translate to a decrease in bleeding complications [16–18]. Evidence from registry and limited clinical trial data exists for reduction in bleeding risk with VCD use combined with the use of bivalirudin [19, 20]. Overall, however, there is significant heterogeneity in studies assessing VCD use because of a multitude of different devices being available, differences in operator experience, and bias in selection for use of a VCD versus manual compression for hemostasis. The use of a VCD does not substitute for standard postcatheterization care.Operators who regularly use closure devices should understand the potential complications associated with each device. These include acute closure of the CFA, infection, and excessive inflammatory reaction. As there is some increased risk of potential infection, antibiotic administration at the time of closure may be considered.

If the operator chooses not to use a VCD or one is not available, manual compression remains the gold standard. However, proper hold must be ensured to achieve adequate hemostasis. Assurance that the level of the anticoagulant chosen is subtherapeutic,if appropriate, is necessary to minimize bleeding/hematoma risk. The proper technique in applying manual pressure is particularly important in the current era of predominant radial access, as staff may not be as familiar with manual pressure application for femoral closure.

When to Consider a Primary Femoral Approach

Special Populations

Femoral artery access may be the preferred option in certain subsets of patients. Access of the radial artery, although generally safe, has been thought to potentially increase the risk of damage to the radial artery. In turn, patients who may need maintenance of radial artery patency, such as predialysis patients in whom arteriovenous shunts may be placed, or others who may have the radial artery harvested as a coronary bypass conduit, should be accessed via a femoral approach. Use of the radial artery in patients with preexisting arteriovenous shunts is generally avoided. Femoral access should be considered in patients with known difficult radial anatomy or innominate anatomy from a prior catheterization experience. Also, those patients with a history of coronary artery bypass graft may sometimes be better suited for femoral access as, although the left internal mammary artery is generally easy to engage via left radial access, this approach may impair routine engagement of other grafts.

From an interventional standpoint, femoral access may be preferred in cases where the previous diagnostic or PCI attempt was challenging from the radial approach. This may occur in the setting of tortuous anatomy and/or in a situation where more supportive equipment may be needed, and either the radial artery diameter is marginal for more than 6-Fr access or guide support is suboptimal from a radial approach. This is particularly true for treatment of chronic total occlusions. Although there are very experienced operators who perform chronic total occlusion interventions via a radial approach alone, this is generally not the standard yet.

Training Cardiology Fellows

Femoral Access Proficiency and Complications: Does a Radial Paradox Exist?

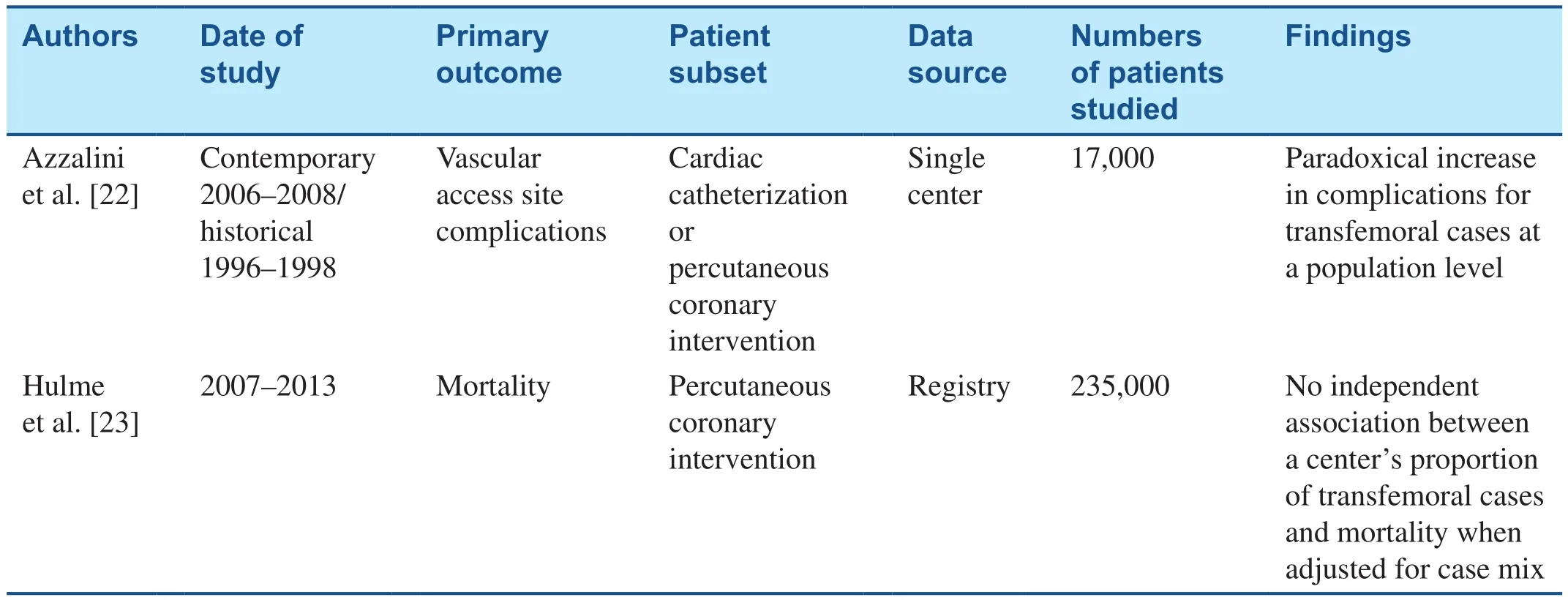

Current guidelines from the American College of Cardiology dictate a specific number of catheterizations be performed by all cardiology fellows for them to be deemed proficient. However, per the last update in 2015, there is no specification regarding the number of femoral versus radial cases [21].Although there are data regarding an adequate volume of radial cases for proficiency, there are no clear data regarding femoral access. This raises the question of how much femoral experience one needs to be proficient. Some studies have looked at the learning curve for radial access proficiency, but a similar assessment for femoral access is unknown.The implications of such a question are far-reaching beyond just obtaining access, and are also relevant for learning closure device skills, which are crucial for structural interventions. Additionally, there has been some thought among interventionalists that primary radial operators may be likelier to experience femoral access–related complications. This has been referred to as theradial paradox– proficiency in femoral access may atrophy over time, or femoral access training may have been suboptimal compared with radial access training. Whether this is really the case can be debated, although some data,albeit limited, support these concerns, and the two most robust, recent analyses of this topic are listed in Table 1. Azzalini et al. [22] compared a contemporary cohort of patients (primary radial approach)with a historical cohort (primary femoral approach).More than 17,000 patients were included in the analysis including all patients undergoing diagnostic and therapeutic catheterizations. Azzalini et al. found that femoral access patients in the modern cohort experienced more vascular complications than thehistorical cohort. However, there is some confounding bias in that patients in whom femoral access was used also had more concomitant venous femoral access as well as the need for an intra-aortic balloon pump, suggesting higher case acuity. Additionally,whether these results were related to overall radial volume and/or additional confounding bias by indication (i.e., bias toward more femoral access in patients who were critically ill) is uncertain. Recent data from Hulme et al. [23], however, revealed no increase in femoral complications with radial transition. No definitive answer to this question exists;however, overall the data seem to favor the need for a balanced approach to training, such that contemporary cardiology fellows should receive adequate training in both access sites. This may require a shift in some academic institutions that have transitioned to a primary radial approach. Attending surgeons should be aware of such an environment and actively engage fellows in selecting cases that may be better suited for a femoral approach. Additionally, the use of training simulators to promote focused teaching regarding femoral access may be useful. Revised guidelines from cardiovascular societies may also assist in promoting the need for a more diverse approach to access-site training.

Table 1 Summary of Femoral Access Complication Trends with the Introduction of the Radial Approach.

Gaps in Knowledge

Although efforts to transition more operators to a primary radial approach have progressed, the need to maintain proficiency in femoral access remains.However, the ideal method to maintain and train for these skills is unknown. Further studies should focus on prospective study of best practices for femoral access as well as more specific identification of proficiency numbers for training. Whether a potential radial paradox truly exists, at an operator or institutional level, should remain important and warrants further investigation.

Future Directions for Femoral Access

As the field of interventional cardiology continues to progress rapidly, the importance of adequate training in safe arterial access for cardiac catheterization and advanced structural interventions continues to increase. The data for the safety of radial access continue to expand and extend to reduction in adverse clinical outcomes. However, there will always be a need for femoral access in specific cases as well as for advanced, higher-risk, complex coronary interventions and structural interventions.Going forward, conscious efforts should be made to promote best practices and provide adequate training for safe femoral access.

Conflict of lnterest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Cardiovascular Innovations and Applications2018年3期

Cardiovascular Innovations and Applications2018年3期

- Cardiovascular Innovations and Applications的其它文章

- Cardiovascular Innovations and Applications

- Persisting Angina after Successful Surgical Removal of a Large Coronary Artery Aneurysm Attached to the Proximal Portion of the Left Circumflex Artery: Role of Coronary Artery Spasm

- Speckle Tracking Echocardiography ldentifies lmpaired Longitudinal Strain as a Common Deficit in Various Cardiac Diseases

- Bioresorbable Vascular Scaffold in the Midportion of the Left Anterior Descending Artery for Cardiac Allograft Vasculopathy in a Cardiac Transplant Patient

- The Use of Direct Oral Anticoagulants for Prevention of Stroke and Systemic Embolic Events in East Asian Patients with Nonvalvular Atrial Fibrillation

- Current Status of Coronary Atherectomy