Effects of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation on cognitive function and cholinergic activity in the rat hippocampus after vascular dementia

Xiao-Qiao Zhang , Li Li, Jiang-Tao Huo Min Cheng Lin-Hong Li

Abstract Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) is a non‐invasive treatment that can enhance the recovery of neurological function after stroke. Whether it can similarly promote the recovery of cognitive function after vascular dementia remains unknown. In this study,a rat model for vascular dementia was established by the two‐vessel occlusion method. Two days after injury, 30 pulses of rTMS were ad‐ministered to each cerebral hemisphere at a frequency of 0.5 Hz and a magnetic field intensity of 1.33 T. The Morris water maze test was used to evaluate learning and memory function. The Karnovsky‐Roots method was performed to determine the density of cholinergic neurons in the hippocampal CA1 region. Immunohistochemical staining was used to determine the number of brain‐derived neurotroph‐ic factor (BDNF)‐immunoreactive cells in the hippocampal CA1 region. rTMS treatment for 30 days signi ficantly improved learning and memory function, increased acetylcholinesterase and choline acetyltransferase activity, increased the density of cholinergic neurons, and increased the number of BDNF‐immunoreactive cells. These results indicate that rTMS can ameliorate learning and memory de ficiencies in rats with vascular dementia. The mechanism through which this occurs might be related to the promotion of BDNF expression and subsequent restoration of cholinergic system activity in hippocampal CA1 region.

Key Words: nerve regeneration; cholinergic system; neurotrophic factor; hippocampal CA1 region; learning and memory function; repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation; vascular dementia; neural regeneration

Introduction

After Alzheimer’s disease, vascular dementia (VaD) is the second most common type of dementia in older people worldwide, accounting for approximately 15—20% of all de‐mentia cases (O’Brien and Thomas, 2015; Smith, 2017). VaD is characterized as an acquired cognitive impairment and intellectual dysfunction syndrome resulting from ischemic,ischemic‐hypoxic, or hemorrhagic brain injury owing to cardiovascular disease and pathological changes in the car‐diovascular system (Román, 2002, 2004). The pathogenesis of VaD is inadequately understood. Studies have shown that,similar to Alzheimer’s disease, cholinergic de ficits and dis‐ruption of cholinergic pathways that occur in some patients with VaD may contribute to cognitive impairment (Perry et al., 2005; Xiao et al., 2012). Cholinergic neurons that project into the hippocampus are known to play an important role in learning and memory function (Haam and Yakel, 2017;Prado et al., 2017). Cholinergic terminals in presynaptic membranes are very sensitive to ischemic insults, which inevitably leads to cholinergic abnormalities. These cholin‐ergic abnormalities observed in VaD, including changes in acetylcholinesterase (AChE) and choline acetyltransferase(ChAT) activity, provide a theoretical explanation for the therapeutic bene fits of cholinesterase inhibitors such as do‐nepezil and rivastigmine in VaD (Román et al., 2005; Kan‐diah et al., 2017). Aside from cholinesterase inhibitors, there are currently few effective interventions for VaD treatment.Thus, developing additional therapeutic approaches for VaD is an urgent need.

Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) is a noninvasive neurological treatment technique that was initially used in the 1980s for detecting and evaluating nerve function. Subsequent in‐depth research has shown that it can have a therapeutic effect on depression and other neu‐ropsychiatric disorders, Parkinson’s disease, and cerebral ischemia. It works by modulating neurotransmitters release,affecting the excitability of the cerebral cortex and synaptic plasticity, preventing delayed neuronal death, and enhanc‐ing neurogenesis (Tarhan et al., 2012; Yang et al., 2013; Rod‐ger and Sherrard, 2015; Luo et al., 2017). Recently, rTMS gained attention after it was demonstrated to have thera‐peutic effects in cases of stroke (Aşkın et al., 2017; Meng and Song, 2017). Knowing this, we hypothesized that rTMS might also be an effective therapeutic approach for VaD,which is a subtype of cerebral vascular disease. The current study attempted to clarify the therapeutic effects of rTMS on rats with VaD and explore the underlying mechanism for regulating cholinergic system activity.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Fifty‐four male Sprague‐Dawley rats (aged 12 weeks and weighing 200—250 g) were obtained from the Center of Ex‐perimental Animal, Hubei University of Medicine, China(No. SCXK‐E‐20160032). Rats were housed six per cage in a regulated environment at 25 ± 2°C and a 12‐hour light/dark cycle. The rats were randomly and equally divided into sham group, sham rTMS group, and rTMS group. The rats were allowed free access to adequate water and a standard diet.The experimental protocols were approved by the Animal Care Committee of Hubei University of Medicine in China(approval No. 2016026).

Establishing the VaD animal model

Bilateral common carotid artery occlusion was performed to produce VaD rat model, as previously described by Ni et al. (1994). This is the most popular method for generating the VaD rat model. Rats were intraperitoneally anesthetized with 10% (v/v) chloral hydrate (350 mg/kg; Sigma, St. Louis,MO, USA). The bilateral common carotid arteries were ex‐posed with an anterior neck median incision and carefully separated from the surrounding tissues. Then, the common carotid arteries were ligated with suture permanently. Rats in the sham group were subjected to the same surgical pro‐cedure without occlusion of arteries.

rTMS treatment

rTMS was implemented with a magnetic stimulator (Dantec Corporation, Copenhagen, Denmark; maximum stimulus intensity: 1.9 Tesla) and round coil (Dantec Corporation;outer diameter: 12 mm). Starting from the 2ndday after the operation, rats in the rTMS group were given rTMS treat‐ment twice a day (once for each cerebral hemisphere). Each treatment was 30 pulses, stimulation frequency was 0.5 Hz, and the magnetic field intensity was 1.33 Tesla (70% of threshold). Rats in the sham rTMS group were treated with a simulated rTMS in which their heads were fixed in the head coil without magnetic stimulation. The stimulation was delivered at 9 a.m. and 5 p.m. daily . The treatment lasted for 4 weeks and finished on the day before the water maze test was conducted to evaluate learning and memory function.

Water maze test of spatial learning and memory

Thirty days after the surgery, the Morris water maze test was administered to evaluate learning and memory function in each group of rats, as previously described with slight mod‐ifications (Morris, 1984). A circular galvanized steel water tank (200‐cm diameter and 50‐cm height) with four quad‐rants was used. The water temperature was adjusted to 22 ±2°C. A hidden platform (12 cm in diameter) that served as the escape platform was submerged 2 cm below the water surface and placed at the midpoint of a fixed quadrant. On the first 4 consecutive days, the rats were put into the water and required to find the location of the hidden platform and climb onto it. The average time required to complete the task was called full average escape latency. All rats underwent two trials per day, at intervals of 8 hours. The rat was regard‐ed to have found the platform if it stayed there for 2 seconds.If the rat failed to find the platform within 180 seconds, it was guided to climb onto the platform and kept there for 60 seconds to become familiar with the environment and the platform position. In these cases, escape latency was recorded as 180 seconds. On day 5, a spatial probe trial was performed. The platform was removed from the pool, and each rat was allowed to search the maze for 3 minutes. The trajectory beginning with the rat’s entry into the water from the first quadrant and the number of platform area crossings were recorded. After the water‐maze test was complete, the AChE and ChAT activity assays, cholinergic staining, and immunohistochemical staining were performed.

AChE and ChAT activity assays

Six randomly selected rats from each group were intraper‐itoneally anesthetized with 10% chloral hydrate and their brains were quickly removed. Unilateral hippocampi were dissected into Petri dishes placed on ice. For enzymatic ac‐tivity determinations, hippocampal tissue was homogenized in 10 volumes of 0.15 M NaCl. After centrifugation, the su‐pernatants were extracted. AChE and ChAT activities were spectrophotometrically measured with the corresponding commercial kits (Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Insti‐tute, Nanjing, China). With acetyl coenzyme A and choline as the substrate, the reactant combined with the reagent,under the action of ChAT. Conjugate absorbance was deter‐mined, representing the ChAT activity. AChE activity was measured according to AChE hydrolysis of acetylcholine into choline and acetic acid. Choline reacted with sulfhydryl reagent to form symtrinitrobenzene, a yellow compound.Colorimetry was used to determine the color depth, which represented the level of AChE activity.

Cholinergic neuron staining

Another 6 randomly selected rats from each group were deeply anesthetized and perfusion‐fixed with 4% parafor‐maldehyde. The brain was removed and frozen, and the hip‐pocampus was sliced into continuous 30‐μm thick coronal sections. The frozen sections were put on slides and washed twice with phosphate buffered saline (PBS), 5 minutes each time, after adhering to the slide. The slices were placed in flu‐id (iodide acetylthiocholine 6.25 mg, 0.82% sodium acetate 7.9 mL, 0.6% acetic acid 0.25 mL, 2.94% sodium citrate 0.6 mL,0.75% copper sulfate 1.25 mL, 0.165% potassium ferricyanide 1.25 mL, 0.137% tetraisopropylpyrophosphamide 0.25mL,and double distilled water 1 mL) and incubated at 37°C for 2 hours. Then, they were washed twice with PBS, each time for 5 minutes. After the reaction was complete, the sections were rinsed in 5 mg 3,3′‐diaminobenzidine, Tris‐HCl 1 mL, 3%nickel ammonium sulfate 10 mL, and H2O21 mL for 15 min‐utes for coloration. The sections were then washed again with PBS, dehydrated, cleared, and mounted regularly. The density of cholinergic neurons in the CA1 region of hippocampus was observed with a light microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Ja‐pan) and measured with the HPIAS‐1000 computer‐assisted image‐analyzing system (image‐analysis software developed by Tongji University, China).

Immunohistochemical staining

The remaining 6 rats from each group were anesthetized with an overdose of 10% chloral hydrate and sacri ficedviaintracardial perfusion with saline and 4% paraformaldehyde.The brains were harvested and post‐fixed in the fixative(described above) overnight at 4°C. The tissue was cleared with 70% ethanol and embedded with paraffin. The blocks that included the hippocampus were serially sectioned into 5‐μm thick coronal slices. The sections were deparaffinized in xylene, rehydrated, treated with 3% H2O2in methanol for 10 minutes at room temperature, and subjected to heat‐in‐duced antigen retrieval in a microwave oven. The sections were washed 3 times (5 minutes each time) with 0.1 M PBS.After incubating with normal goat serum for 20 minutes,the sections were subsequently incubated with rabbit an‐ti‐brain‐derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) monoclonal antibody (1:200; Sigma‐Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) at 4°C overnight. The slides were then processed for immunohis‐tochemical staining by the SP method according to the kit(Sigma) instruction. In turn, a secondary antibody (bioti‐nylated anti‐rabbit IgG produced in goat) and horseradish peroxidase labeled streptavidin (Sigma‐Aldrich) were added to the sections, which were incubated with primary antibod‐ies. Following coloration with 3,3′‐diaminobenzidine‐H2O2and counterstaining with hematoxylin, the slides were visual‐ized through a microscope and the images were processed on the HPIAS‐1000 computer‐assisted image analyzing system.

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as the mean ± SD and were processed by SPSS 16.0 statistical software (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA).Results were analyzed using one‐way analyses of variance.Post-hoccorrection for multiple comparisons was performed using the Student‐Newman‐Keuls test. A value ofP< 0.05 was considered statistically signi ficant.

Results

rTMS improved learning and memory ability in VaD rats

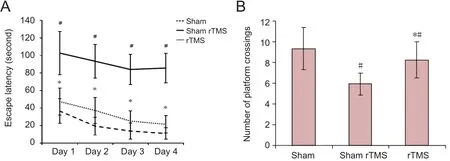

From day 1 to day 4, all rats exhibited steadily decreasing es‐cape latency in the Morris water maze. However, the lower escape latency within any group did not change signi ficantly even by the 4thday (P> 0.05). Between‐group comparisons showed that compared with the sham group, escape latency was longer and the number of platform crossings was small‐er in the sham rTMS group from day 1 to day 4 (P< 0.05).Escape latency was shorter and the number of platform crossings was greater in the rTMS group than in the sham rTMS group from day 1 to day 4 (P< 0.05). Furthermore,compared with the sham group, escape latency was longer and the number of platform crossings was smaller in the rTMS group from day 1 to day 4 (P< 0.05; Figure 1).

rTMS increased AChE and ChAT activities in the hippocampus of VaD rats

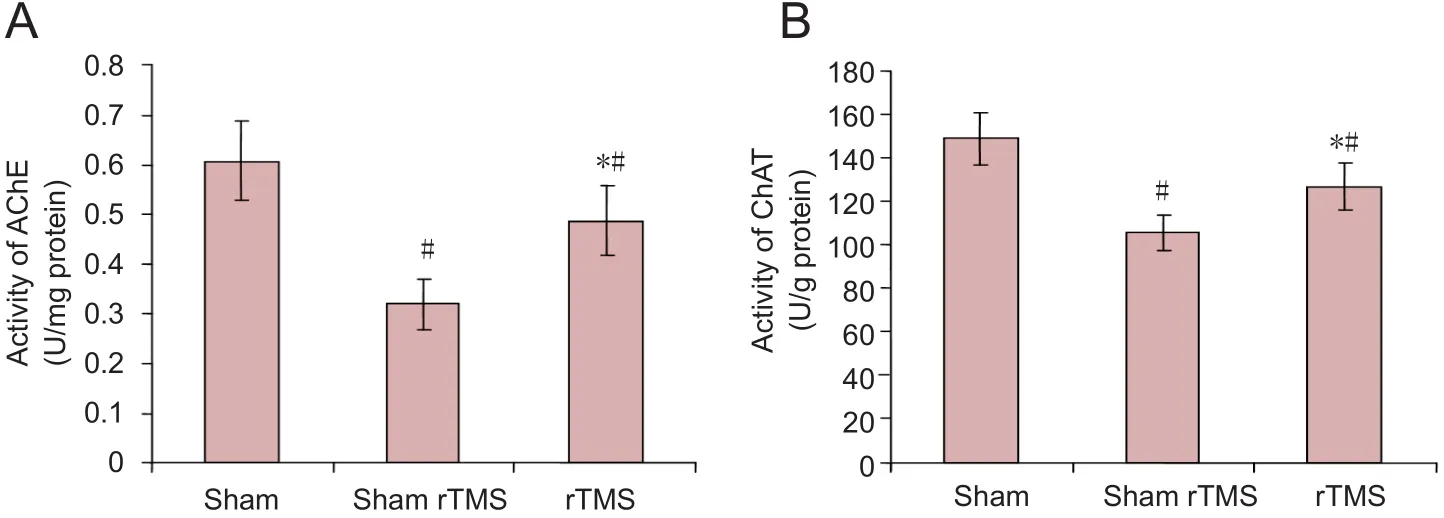

AChE and ChAT activities were signi ficantly higher in the sham group than in the sham rTMS or rTMS groups (P<0.05). Among the VaD model mice, AChE and ChAT ac‐tivities in the hippocampus of the rTMS group were signi fi‐cantly higher than those in the sham rTMS group (P< 0.05;Figure 2).

rTMS increased the number of cholinergic neurons in the hippocampal CA1 zone of VaD rats

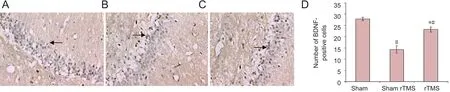

We observed thick and well‐distributed cholinergic neurons in the hippocampal CA1 zones of the sham group. In con‐trast, cholinergic neurons were sparsely distributed and thin in the hippocampal CA1 zone of the sham rTMS and rTMS groups (P< 0.05). However, the density of cholinergic neu‐rons in the hippocampal CA1 zone was signi ficantly higher in the rTMS group than in the sham rTMS group (P< 0.05;Figure 3).

rTMS increased the number of BDNF-immunoreactive cells in the hippocampal CA1 zone of VaD rats

The number of BDNF‐immunoreactive cells in the hippo‐campal CA1 zone varied groups (Figure 4A–C). The num‐ber of BDNF‐immunoreactive cells in the sham rTMS and rTMS groups was less than that in the sham group (P< 0.05;Figure 4D). Among the VaD model mice, the number of BDNF‐immunoreactive cells was much greater in the rTMS group than in the sham rTMS group (P< 0.05; Figure 4D).

Figure 1 rTMS improved performance on the Morris water maze in rats with vascular dementia.

Figure 2 Effect of rTMS on the AChE (A)and ChAT (B) activity in the hippocampus of rats with vascular dementia.

Figure 3 Effect of rTMS on the number of cholinergic neurons in the hippocampal CA1 zone of rats with vascular dementia.

Figure 4 Effect of rTMS on the number of BDNF-immunoreactive cells in the hippocampal CA1 zone of rats with vascular dementia.

Discussion

Cognitive impairment is a major characteristic of VaD.Hippocampal activity is highly associated with memory and learning abilities, and is one of the brain regions that is most sensitive to ischemic and hypoxic injuries. Thus, the hippo‐campus, especially the hippocampal CA1 area, is thought to be the prime target in the brain for damage induced by bilat‐eral common carotid artery occlusion (Farkas et al., 2007).Ischemia and hypoxia may lead to the loss of pyramidal neu‐rons in the hippocampal CA1 region, which inevitably induc‐es cognitive de ficits (Anastácio et al., 2014). The pathogenesis of VaD may be associated with cholinergic de ficits, and cho‐linergic therapies have therefore resulted in improved cogni‐tive function in patients with VaD (Cao et al., 2016). Cholin‐ergic neurons that project into the hippocampus are essential for learning and memory. The cholinergic terminals in the presynaptic membrane are also sensitive to ischemic insults.In the present study, we discovered that cholinergic neurons in the hippocampal CA1 area were sparsely distributed and thin in sham rTMS and rTMS groups due to ischemic inju‐ry. These findings can partially explain the cognitive de ficits observed in the two model rat groups. Cholinergic changes in the hippocampus have been reported to be related to spa‐tial learning and memory impairment (Wang et al., 2012;Kim et al., 2013). Acetylcholine (ACh) is a major choliner‐gic neurotransmitter in brain that plays a critical role in the processing of learning and memory (Hasselmo, 2006). AChE is a biological enzyme that breaks down ACh that has been released into the synapse, thus promptly inhibiting the action of Ach. This process is essential for normal function of the nervous system (Provensi et al., 2016). ChAT is a cholinergic marker that also takes part in the synthesis of Ach. Cognitive dysfunction is correlated with the loss of cholinergic neurons and the decline of ChAT levels. AChE and ChAT are crucial enzymes that regulate the availability of Ach. In this study, we found a significant decrease in AChE and ChAT activity in the hippocampus of VaD animals, which was in accordance with abnormalities in cholinergic neurons.

Previous studies have reported a neuroprotective effect of rTMS for cerebral ischemia through increased velocity of focal cerebral blood flow, promotion of BDNF expression in brain tissue adjacent to the infarction, and a reduction of ischemic insult‐induced neuronal apoptosis in peri‐isch‐emic brain areas (O’Shea and Walsh, 2007; Zhang et al.,2007; Yoon et al., 2011; Luo et al., 2017). We also found that rTMS could promote the expression of BDNF in the hip‐pocampal CA1 region of VaD model rats whose condition was caused by a special bilateral common carotid artery ligation‐induced cerebral ischemia. Accumulating evidence has documented the critical role of the neurotrophin BDNF in regulating the maintenance, survival, and growth of neurons (Schinder and Poo, 2000). We presume that rTMS ameliorated the reduction in AChE and ChAT activity and the loss of cholinergic neurons in the hippocampus of VaD rats because of the increased BDNF expression. BDNF can also enhance synaptic transmission and neuronal plasticity in the central nervous system (Mizuno et al., 2000), resulting in increased learning and memory capability. The learning and memory capabilities of rats in the rTMS group were not completely restored to the level observed in rats from the sham group. This indicates that the therapeutic effects of rTMS for VaD rat have a limit.

rTMS is a neuromodulatory technique that induces deep currentviamagnetic pulses in a safe, noninvasive, and pain‐less way, and can affect brain physiology. Different rTMS techniques have been used to promote stroke rehabilitation(Yozbatiran et al., 2009; Khedr and Fetoh, 2010). The most exciting characteristic of rTMS is that different parameters can produce different modulatory effects. For example,high‐frequency rTMS (> 5 Hz) increases cortical excitability and leads to long‐term potentiation‐like effects. In contrast,low‐frequency rTMS (< 1 Hz) reduces cortical excitability and leads to long‐term depression (Houdayer et al., 2008).Whether low‐frequency rTMS or high‐frequency rTMS is better for improving neurological impairments in ischemic stroke is still unknown. Müller et al. (2000) reported an in‐crease in BDNF expression after high‐frequency rTMS. Luo et al. (2017) demonstrated that high‐frequency rTMS could promote functional recovery by enhancing neural regener‐ation and activation of BDNF/TrkB signaling in ischemic rats. In our previous study, low‐frequency rTMS was bene‐ficial for neural recovery and could promote the expression of BDNF in the margin of cerebral ischemia (Zhang et al.,2007). A recent clinical research study reported that low‐fre‐quency rTMS improved motor dysfunction in patients after cerebral infarction (Meng and Song, 2017). More impor‐tantly, it has less risk of inducing epilepsy and seems safer after stroke. Based on these reasons, low‐frequency rTMS was selected as a therapeutic strategy for VaD.

In summary, low‐frequency rTMS improves learning and memory function of VaD model rats. The underlying mecha‐nisms include enhanced neuroprotection as a result of BDNF expression and restoration of hippocampal cholinergic sys‐tem activity. Our results indicate that rTMS is a promising strategy for VaD therapy. Nevertheless, the study had limita‐tions. We only tested the therapeutic effect of one stimulation parameter (low‐frequency rTMS) and the sample size in each group was low. As this was an exploratory study, further in‐vestigation is needed. Ascertaining the optimal frequency and intensity of rTMS for recovery of cognitive function in VaD rats will be important for future studies that hope to apply this technique to human patients with VaD.

Acknowledgments:We would like to thank staff from the Center of Experimental Animals, Hubei University of Medicine for animal providing and raising and technical assistance.

Author contributions:XQZ participated in conception, design and performance of the study, and wrote the paper. LL designed the study and was in charge of cognitive function appreciation, data collection, analysis and interpretation. JTH and MC were in charge of animal model establishment and rTMS treatment. LHL implemented specimen disposal and detection. All authors approved the final version of the paper.

Conflicts of interest:We declare that we have no con flict of interest.

Financial support:This study was supported by a grant from the Major Project of Educational Commission of Hubei Province of China, No.D20152101. The conception, design, execution, and analysis of experiments, as well as the preparation of and decision to publish this manuscript, were made independent of the funding organization.

Institutional review board statement:This study was approved by the Animal Care Committee of Hubei University of Medicine in China (approval No. 2016026). The experimental procedure followed the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals(NIH Publications No. 8023, revised 1985).

Copyright license agreement:The Copyright License Agreement has been signed by all authors before publication.

Data sharing statement:Datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Plagiarism check:Checked twice by iThenticate.

Peer review:Externally peer reviewed.

Open access statement:This is an open access journal, and articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak,and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as appropriate credit is given and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

- 中国神经再生研究(英文版)的其它文章

- In Memoriam: Ray Grill (1966–2018)

- Structural brain volume differences between cognitively intact ApoE4 carriers and non-carriers across the lifespan

- Roles of Eph/ephrin bidirectional signaling during injury and recovery of the central nervous system

- Neuroplasticity, limbic neuroblastosis and neuro-regenerative disorders

- A tissue-engineered rostral migratory stream for directed neuronal replacement

- Targeting the noradrenergic system for anti-in flammatory and neuroprotective effects:implications for Parkinson’s disease