Neuroplasticity, limbic neuroblastosis and neuro-regenerative disorders

Mahesh Kandasamy , Ludwig Aigner

AbstractThe brain is a dynamic organ of the biological renaissance due to the existence of neuroplasticity. Adult neurogenesis abides by every aspect of neuroplasticity in the intact brain and contributes to neural regen‐eration in response to brain diseases and injury. The occurrence of adult neurogenesis has unequivocally been witnessed in human subjects, experimental and wildlife research including rodents, bats and ce‐taceans. Adult neurogenesis is a complex cellular process, in which generation of neuroblasts namely,neuroblastosis appears to be an integral process that occur in the limbic system and basal ganglia in addi‐tion to the canonical neurogenic niches. Neuroblastosis can be regulated by various factors and contributes to different functions of the brain. The characteristics and fate of neuroblasts have been found to be dif‐ferent among mammals regardless of their cognitive functions. Recently, regulation of neuroblastosis has been proposed for the sensorimotor interface and regenerative neuroplasticity of the adult brain. Hence,the understanding of adult neurogenesis at the functional level of neuroblasts requires a great scienti fic attention. Therefore, this mini‐review provides a glimpse into the conceptual development of neuroplasti‐city, discusses the possible role of different types of neuroblasts and signi fies neuroregenerative failure as a potential cause of dementia.

Key Words: neuroplasticity; adult neurogenesis; neuroblasts; reactive neuroblastosis; hippocampus; ultrasound;neuroregenerative disorders; neotrophy; echolocation

Introduction

Neuroplasticity has expediently been intended to the innate adaptability of the brain to restructure its biological reso‐nance towards the personal experience, environmental stim‐uli and disease throughout life (Cramer et al., 2011; Fuchs and Flügge, 2014). The structural and functional alterations of the brain can proceedviacellular events, biochemical pathways, synaptic remodeling and behavioural aspects in order to maintain the cerebral homeostasis and to facilitate neurological rehabilitation (Cramer et al., 2011). The regu‐lation of neuroplasticity has been linked to variable factors like nutrition, education, physical activity, enriched envi‐ronment, sensory inputs, emotion, and fecundity. In con‐trast, abnormal lifestyle, genetic variants, ageing, infirmity or injury appear to exacerbate neuroplasticity leading to movement symptoms, behavioural disorders and dementia(Mufson et al., 2015). Historically, William James (1842–1910) introduced the term neuroplasticity as a key biological module of psychological process (Berlucchi and Buchtel,2009). Eugenio Tanzi (1856–1934) proposed that the neuro‐biology of learning might be constituted at potential vicinity between nerve endings in the brain (Peccarisi et al., 1994).Ernesto Lugaro (1870–1940) identi fied an intermediary type of neuron (Lugaro Cells) and emphasized that a bidirec‐tional communication between nerve cells might be liable for the neuroplasticity of the brain (Berlucchi and Buchtel,2009). Otto Dieters’ (1834–1863) illustration of the axon,dendrites, and non‐neuronal cells went largely unnoticed until Max Schultze (1825–1874) reasserted it (Deiters and Guillery, 2013; Voogd, 2016). Ramón y Cajal (1852–1934)ardently consolidated the neuron doctrine and insisted that the mature brain is an organ of obstinacy (Stahnisch and Nitsch, 2002). His ideology of neuroplasticity remains uncertain, though he noticed that learning could change mi‐crocircuits of the adult brain (Stahnisch and Nitsch, 2002).Richard Semon (1859–1918) proposed a term engram to a possible psychological interface between an intrinsic process and external stimuli, accountable for the neurobiochemical basis of learning (Poo et al., 2016). Karl Lashley (1890–1958)extrapolated the engram that neural substratum of learning might be collectively dynamic and distributed throughout cortices of the brain (Bruce, 2001). While Jerzy Konorski(1903–1973) recognized that the pre‐existing circuits could reversibly be swapped between neurons upon sensory inputs(Zieliński, 2006), Charles Sherrington (1857–1952) devel‐oped the concept of synapse formation for the integrative action of the neurons during muscle contraction and re flex(Molnár and Brown, 2010). Donald Hebb’s (1904–1985)postulate of cell assemblies through synaptic remodeling termed synaptic plasticity laid a sturdy foundation for the neurobiology of learning and memory (Brown and Milner,2003; Josselyn et al., 2017). Henry Dale (1875–1968) and Otto Loewi (1873–1961) have identi fied that synaptic trans‐mission at nerve terminals actviapotential chemical mes‐sengers known as neurotransmitters (Tansey, 2006; McCoy and Tan, 2014). Theodor Bethe (1872–1954) and Paul Bach‐y‐Rita (1934–2006) supported the idea that neuroplasticity can be exchanged between different regions of the normal brain thereby the functional loss of a brain area can be indem‐nified by a physiologically intact region (Bach‐y‐Rita, 2001,2003; Stahnisch, 2016). During 1980s, Eric Kandel provided the experimental proof for a reciprocal relation between the biochemical alteration, neuronal gene expression and synaptic plasticity along learning and behavioural outcome (Kandel,1981; Kandel and Schwartz, 1982; Siegelbaum et al., 1982).While the adult brain had earlier been considered a stagnant organ, neuroplasticity had majorly been focused on the chang‐es that occur at the synaptic connections. Indeed, there had generally been a great scienti fic challenge in understanding the structural and functional changes of the brain as it required a dynamic cellular process in response to the learning process and environmental stimuli (Ming and Song, 2011). However,there has been a gradual paradigm shift in the understanding of neuroplasticity due to a widespread recognition and valida‐tion of the generation of new neurons from neural stem cells in the adult brain. Moreover, the acceptance of the functional role of new neurons in the adult brain has revolutionized the concept of neuroplasticity and neurobiology of behaviour,learning and memory functions.

The Neuroplasticity Role of Adult Neurogenesis

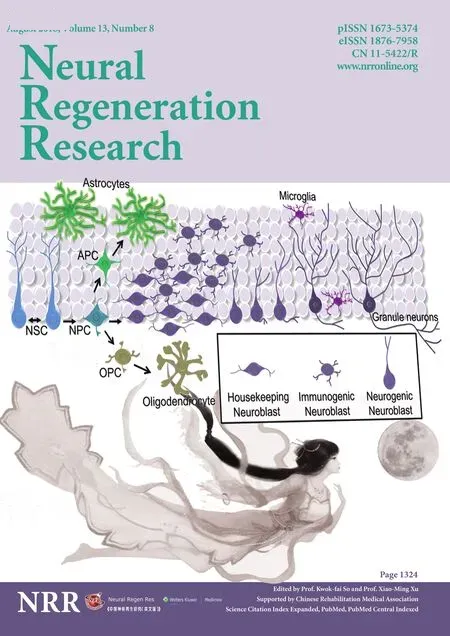

In 1960s, Joseph Altman (1925–2016) and Gopal Das (1933–1991) provided an initial evidence for the mitotic activity of neural precursors in the adult brain thereby scintillated a possibility for the generation of new neurons in adulthood(Altman and Das, 1965). It took several years to accept this notion, while the neuropoiesis in the mature brain, namely adult neurogenesis, has long been challenged, validated,attributed to cognitive functions and neural regeneration.Adult neurogenesis originates in the hippocampus and SVZ through the generation of neuroblasts or immature neurons(neuroblastosis) from neural stem cells (NSCs) in the brain(Figure 1) (Ming and Song, 2011; Couillard‐Despres et al.,2005). Besides, the occurrence of adult neurogenesis has also been recognized in the cortex, amygdala, hypothalamus,and striatum that are known to functionally be associated with the limbic system and basal ganglia of the brain (Gould et al., 1999; Jhaveri et al., 2018; Paul et al., 2017; Kohl et al.,2010; Ernst et al., 2014; Kandasamy et al., 2015; Kandasamy and Aigner, 2018). Several lines of evidence support that adult neurogenesis can compromise key features of neu‐roplasticity hence 1) it appears to be regulated by various intrinsic factors and extrinsic stimuli (Kempermann et al.,1997; Ming and Song, 2011), 2) it provides cellular founda‐tion for the pattern separation, social adaptation, regulation of mood, desire, olfaction, learning and memory (Zhao et al.,2008; Gonçalves et al., 2016) and 3) it denotes the regenera‐tive potential of the brain against late‐onset brain disorders(Kandasamy and Aigner, 2018). However, the molecular and cellular process associated with adult neurogenesis has not been completely understood. While the knowledge on regulation of adult neurogenesis at the level of NSCs main‐tenance and proliferation has been significantly improved(Kandasamy et al., 2010), underlying regulatory mechanisms of the generation, maintenance and fate of neuroblasts and their functional signi ficance in the adult brain remains to be fully established.

Functional Signi ficance and Types of Neuroblasts in the Adult Brain

The role of the hippocampus has been implemented to cog‐nitive functions whereas irreversible failure in hippocampal neurogenesis has been attributed to dementia (Hollands et al., 2016). Of the abundant number of neural precursor cells produced in the adult brain, a very low number of new neu‐rons are likely to be integrated into the hippocampus (Spal‐ding et al., 2013). Why does the adult brain need to support the generation of the surplus amount of neuroblasts in the neurogenic niches? There has been an enormous amount of evidence suggesting that 1) neuroblasts are heterogeneous in nature with multipotential capacity (Moody, 1998; Walker et al., 2007), 2) neuroblasts have a robust migratory poten‐tial (Khlghatyan and Saghatelyan, 2012; Kaneko et al., 2017),3) neuroblasts appear to be modulated by sensorimotor in‐puts (van Praag et al., 1999; Kandasamy and Aigner, 2018),4) neuroblasts represent limbic‐motor interface (Kandasamy and Aigner, 2018), 5) neuroblasts can generate action po‐tential (Shuang Liu et al., 2009; Spampanato et al., 2012), 6)neuroblasts can provide neurotrophic support (Platel et al.,2008) and 7) neuroblasts acquire immunological signatures upon brain diseases and injury (Unger et al., 2018). Taken together cellular events of neuroblasts appears to be a mul‐tifaceted process to harmonize and contributes to diverse functions of the brain. Moreover, neuroblasts may provide an ideal model to generate, integrate, store, mobilize and carry forward the substratum of the brain resulting from various inputs including learning.

Figure 1 Schematic representation of stem cells, progenitors, neuronal and glia population of the hippocampus including microglia.

It can be speculated that neuroblasts might be comprised of isogenic cell populations in the adult brain. Thus, three different major classes of neuroblasts can be proposed namely, a) housekeeping neuroblasts, b) neurogenic neu‐roblasts and c) intermediary or immunogenic neuroblasts(Figure 1). Hypothetically, these distinct isogenic neuro‐blasts may represent different forms of neuroplasticity and respond differentially to different learning paradigms, sen‐sorimotor inputs, pathogenesis, and treatment (Kandasamy and Aigner, 2018). Since running wheel exercise has been known to induce mitogenesis of neuronal precursors (van Praag et al., 1999), survival of new neurons in the hippocam‐pus appears to be supported by the enriched environment in quadruped animals (Kempermann et al., 1997). Physical exercise‐mediated sensorimotor input may specifically act on the housekeeping neuroblasts to discharge neurotrophic factors leading to the integration of neurogenic neuroblasts with electrophysiological properties. Likewise, the enriched environment based socio‐psychological wellness may exert a different mode of a molecular signature for neuronal surviv‐al in which changes in neurotransmitter levels may facilitate the integration of neurogenic neuroblasts in the hippocam‐pus. However, prolonged and redundant sensorimotor inputs resulting from learning or exercise may predispose the house‐keeping or intermediary neuroblasts to apoptotic cell death in order to assist the turnover of the neuroblast population. This could partly explain the previous observation of Nora Ar‐bours’ group indicating the speci fic elimination of early phase neuroblasts in the hippocampus during water maze based spatial learning in rodents (Döbrössy et al., 2003). This could also partly address the interpretation of Pasko Rakic that the adult brain may eliminate new neurons to prevent abnormal neural circuitry (Rakic, 2002) while it may not be excluded that integration of neurogenic neuroblasts may represent the synaptic replacement upon neuronal loss.

Role of Neuroblasts in the Cognitive Function of Non-rodent Mammals

Notably, the turnover of hippocampal neurogenesis ap‐pears to be very marginal in Chiroptera (bats) (Amrein et al., 2007) and cetaceans (dolphin and whale) (Patzke et al.,2015). These animals are highly sensitive to seasonal varia‐tion, habitat disturbance, and predators. Therefore, they are likely to undergo a high‐level chronic stress. The reproductive physiology and circadian rhythm are completely different in Chiroptera and cetaceans compared to other animals. While these creatures exploit ultrasonic echolocation for navigation,it may demand high‐level energy expenditure and abnormal sensorimotor inputs (Moss and Surlykke, 2010; Martens et al.,2015). While sheep brain has been shown to sustain the neu‐roblasts without terminal neuronal differentiation (Piumatti et al., 2018), recent reports suggest that non‐newly generated neuroblasts may represent the neuroplasticity of the brain in mammals (Palazzo et al., 2018; Snyder, 2018). Though the brains of cetacean have been characterized by less turnover of neurogenesis, they have been found to have high cognitive ability and social behaviour (Marino et al., 2007). While dol‐phin‐assisted ultrasound therapy has been known to yield posi‐tive effect on cognitive function in human (Fiksdal et al., 2012),transcranial focused ultrasound appears to promote cognitive function in human (Legon et al., 2014). Considering the afore‐mentioned facts, it can be presumed that ultrasound‐mediated cognitive improvement may be facilitated through neuroblasts of the adult brain. Thus neuroblasts in the adult brain might play a major role in learning and memory process. However,future studies directed towards understanding the effects of ultrasound on the regulation of adult neurogenesis and inves‐tigation of the role of neuroblasts in cognitive functions may provide valid clues to improve neuroregenerative plasticity for the betterment of ageing human society.

Reactive Neuroblastosis in Diseased Brains

Hippocampal neurogenesis appears highly vulnerable to ageing, chronic stress, drug abuse and disease, especially in human. The current understanding of the regulation of adult neurogenesis indicates neotrophy (a rapid non‐ma‐lignant cell division subjected to apoptosis) of neuroblasts,recognized as reactive neuroblastosis, in response to early pathogenesis of a diverse range of neurological disorders(Kandasamy and Aigner, 2018). Among them, stroke, ep‐ilepsy, Huntington’s disease, Alzheimer’s disease, Parkin‐son’s disease, Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis, brain injuries and affective disorders collectively share reactive neuroblas‐tosis as a potential hallmark at the early phase of the disease(Kandasamy et al., 2010, 2015; Kandasamy and Aigner,2018). The observed reactive neuroblastosis parallel to ab‐errant neuroimmune response has been proposed to result in mitotic inactivation of NSCs, thereby predisposing the adult brain to abate neurogenic process leading to dementia in the late phase of diseases (Kandasamy et al., 2010, 2015;Kandasamy and Aigner, 2018). In 1998, Fred Gage’s group provided evidence for ongoing hippocampal neurogenesis in the adult human brain (Eriksson et al., 1998). Though a re‐cent report from Alvarez‐Buylla team found no hint for ab‐solute neurogenesis in hippocampus of ageing human brain(Sorrells et al., 2018), a subsequent report by Boldrini M et al., provided again a conclusive evidence of neurogenesis in the adult human brain (Boldrini et al., 2018). The controver‐sial observation from Alvarez‐Buylla group has been highly debated as the negative data on neurogenesis which assumed to be originating from a methodological, technical point or result of a disease and treatment affecting the analyzed adult human brains (Snyder, 2018; Kempermann et al., 2018). The existing knowledge on adult neurogenesis in humans has largely been derived from post‐mortem studies that may not represent the actual status of the brain, for example, due to a long post‐mortem delay until the brain gets fixed. Besides, the expression of glial cell markers in immunogenic neuroblasts and their dispersal in the brain might represent an indication for a neuropathology. The doublecortin (DCX) positive neu‐roblasts have been shown to express ionized calcium‐binding adapter molecule 1 (IBA1) and oligodendrocyte transcription factor 2 (OLIG2) in 13‐year‐old human brain (Sorrells et al.,2018). Surprisingly, the OLIG2 and IBA1 are known to be markers for entirely different glial cell lineages. While the ex‐pression of OLIG2 has been proposed as a negative modula‐tor of neurogenesis, it represents a potential marker of brain tumours. Microglia has been shown to express IBA1 thus the observed DCX/IBA1 double positive neuroblasts indicates a clear sign of immunological response against a neuropatholo‐gy (Unger et al., 2018). Considering the unpredictable nature of mental status, comorbidity and limitations of the brain im‐aging tools, it will be difficult to monitor and demonstrate the complete scenario of neurogenesis in the adult human brain.Thus, the mechanism underlying the regulation and terminal fate of adult neurogenesis actingvianeuroblastosis remains inde finable. However, depending upon the situation, the neu‐roblastosis event might signify the differential role of adult neurogenesis in the brain (Kandasamy and Aigner, 2018).

Conclusion

Functional regeneration is one of the prerequisites for the homeostasis of organisms accountable for the normal lifespan and species conservation. Although regeneration has been im‐plemented to the functional recovery against pathogenesis and injury, ageing poses a fundamental challenge to the regenera‐tive competence of organism. However, the degree of regen‐eration may differ to a great extent among different biological systems along the lifestyle and environmental factors. In gen‐eral, ageing has been a primary risk factor for many metabolic,vascular, malignant and neurocognitive disorders in humans.Among them, the prevalence of dementia is expected to in‐crease many fold in elderly population due to increase in life expectancy worldwide. In general, neurodegeneration is often considered the most common biological cause of dementia.However, we would like to put forward that neuroregener‐ative failure might be more critical for dementia regardless of neurodegeneration. Further, we would like to introduce a term “neuroregenerative disorder” as an additional variable for dementia‐related syndromes that may potentially antago‐nize the manoeuvre of neuroplasticity. Eventually, abnormal

ageing, neurodevelopmental, movement, neuropsychiatric,neuroimmune disorders, stroke, seizure, infectious neurologi‐cal symptoms, chronic stress, depression, obesity, diabetes and hormonal imbalances that show abnormal neurogenesis can be categorized under neuroregenerative disorders. Directive of any therapeutic strategies towards symptomatic manage‐ment for these brain diseases without considering the neu‐roregeneration would be an incomplete attempt to restore the neuroplasticity. Thus, elucidating the neurobiological basis for neuroregenerative failure using advance non‐invasive scientif‐ic tools may provide insight into the functional recovery of the human brain. However, the existence of unanimous putative markers and alternate forms of adult neurogenesis underlying the neuroplasticity cannot be completely excluded. Besides,mammals including cetaceans tend to exhibit a high degree of cognitive function and social behaviour. Recently, neuroblasts have been suggested to compensate the immunogenicity and neuroplasticity of the adult brain thus the ultrasound‐medi‐ated precognitive effect may be mediatingviacirculation of neuroblasts in the mammalian brains. While identi fication of a non‐invasive strategy to boost cognitive function has been a great scienti fic thrust, understanding the biological effect of ultrasound on the regulation of neuroblasts may signify a po‐tential treatment for dementia.

Acknowledgments:MK acknowledges UGC-SAP and DST-FIST for the infrastructure of the Department of Animal Science, Bharathidasan University.

Author contributions:Conceptual writing and illustration: MK; commenting and writing: LA.

Financial support:This work was supported by the FWF Special Research Program (SFB) F44 (F4413-B23) “Cell Signaling in Chronic CNS Disorders”, and through funding from the European Union’s Seventh Framework Program (FP7/2007-2013) under grant agreements n°HEALTH-F2-2011-278850 (INMiND), n° HEALTH-F2-2011-279288(IDEA), n° FP7-REGPOT-316120 (GlowBrain); a startup grant from the Faculty Recharge Programme, University Grants Commission (UGCFRP), New Delhi, India (to MK); a research grant from DST-SERB, New Delhi, India (EEQ/2016/000639) (to MK); an Early Career Research Award (ECR/2016/000741) (to MK).

Copyright license agreement:The Copyright License Agreement has been signed by all authors before publication.

Conflicts of interest:None declared.

Plagiarism check:Checked twice by iThenticate.

Peer review:Externally peer reviewed.

Open access statement:This is an open access journal, and articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak,and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as appropriate credit is given and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

Open peer reviewers:Leonardo Guzman, Universidad de Concepcion, Chile; Hernández-Echeagaray Elizabeth, Universidad Nacional Autonoma de Mexico, Mexico.

Additional file:Open peer review reports 1, 2.

- 中国神经再生研究(英文版)的其它文章

- In Memoriam: Ray Grill (1966–2018)

- Reorganization of injured anterior cingulums in a hemorrhagic stroke patient

- A novel chronic nerve compression model in the rat

- Analgesic effect of AG490, a Janus kinase inhibitor, on oxaliplatin-induced acute neuropathic pain

- Three-dimensional visualization of the functional fascicular groups of a long-segment peripheral nerve

- Novel conductive polypyrrole/silk fibroin scaffold for neural tissue repair