Advanced glycation end products induce neural tube defects through elevating oxidative stress in mice

Ru-Lin Li, Wei-Wei Zhao, Bing-Yan Gao

Laboratory for Development, College of Life Sciences, Northwest University, Xi’an, Shaanxi Province, China

Abstract Our previous study showed an association between advanced glycation end products (AGEs) and neural tube defects (NTDs). To understand the molecular mechanisms underlying the effect of AGEs on neural tube development, C57BL/6 female mice were fed for 4 weeks with com‐mercial food containing 3% advanced glycation end product bovine serum albumin (AGE‐BSA) or 3% bovine serum albumin (BSA) as a control. After mating mice, oxidative stress markers including malondialdehyde and H2O2 were measured at embryonic day 7.5 (E7.5) of ges‐tation, and the level of intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) in embryonic cells was determined at E8.5. In addition to evaluating NTDs,an enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay was used to determine the effect of embryonic protein administration on the N‐(carboxymethyl)lysine reactivity of acid and carboxyethyl lysine antibodies at E10.5. The results showed a remarkable increase in the incidence of NTDs at E10.5 in embryos of mice fed with AGE‐BSA (no hyperglycemia) compared with control mice. Moreover, embryonic protein administration resulted in a noticeable increase in the reactivity of N‐(carboxymethyl) lysine and N(ε)‐(carboxyethyl) lysine antibodies. Malondialdehyde and H2O2 levels in embryonic cells were increased at E7.5, followed by increased intracellular ROS levels at E8.5. Vitamin E supplementation could partially recover these phenomena. Collectively, these results suggest that AGE‐BSA could induce NTDs in the absence of hyperglyce‐mia by an underlying mechanism that is at least partially associated with its capacity to increase embryonic oxidative stress levels.

Key Words: nerve regeneration; neural tube defects; advanced glycation end products; diabetic embryopathy; oxidative stress; N-(carboxymethyl)lysine; malondiadehyde; N(ε)-(carboxyethyl) lysine; embryo; H2O2; bovine serum albumin; neural regeneration

Introduction

Neural tube defects (NTDs) are severe birth defects of the central nervous system. The prevalence of NTDs varies widely between 1 and 10 per 1000 births, depending on geo‐graphic region and ethnic grouping (Au et al., 2010; Machín et al., 2015). Both genetic and non‐genetic factors are in‐volved in the etiology of NTDs (Copp and Greene, 2010;Hall and Solehdin, 2015). Although interventions such as fo‐lic acid supplementation and glucose level control have been recommended to prevent NTDs, a high incidence of NTDs still occurs in rats (Fleming and Copp, 1998; Suhonen, 2000;Loffredo et al., 2001; Liu et al., 2017).

Glycation is the nonenzymatic reaction of glucose or oth‐er reducing sugars with primary amino groups of proteins.Major products of glycation and oxidation of proteins and lipids include advanced glycation end products (AGEs) such as fluorescent pentosidine (Bhat et al., 2014; Siddiqui et al.,2015), non fluorescent Nε‐(carboxymethyl) lysine (CML), and other species (Ramasamy et al., 2005). AGEs are generated in vivo as a normal consequence of metabolism, but their formation is accelerated under conditions of hyperglycemia.Chronic accumulation of AGEs is associated with diabetes,rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus crythematosus, renal in‐sufficiency, in flammation, and aging (Cerami, 1997; Nicholl and Bucala, 1998; Rodriguez‐Garcia, 1998; Mohamed et al.,1999; Schmidt et al., 2000; Singh, 2001). However, the effects of AGEs on embryonic development remain unclear.

The results of a study suggest that AGEs could play an im‐portant role in diabetic embryopathy (Li and Chen, 2014).As AGEs can cause single‐strand breaks in genomic DNA,they can have serious teratogenic effects. While the inci‐dence of congenital abnormalities is not increased in short‐term, pregnancy‐induced hyperglycemia, it is increased if long‐term poor glycemic control predates conception,further implicating a role for AGEs in diabetic embryopathy(Millis, 1988; Eriksson and Wentzel, 2016). Our recent study indicated serum AGEs level to be an important risk factor for NTD occurrence (Li et al., 2014; Daglar et al., 2016).These findings support the notion that AGEs could be an important factor in the mechanism underlying increased in‐cidence of NTDs in diabetic or non‐diabetic mothers.

An abundance of evidence supports the involvement of AGEs in a vicious cycle of inflammation, oxidative stress,ampli fied AGEs production, followed by more in flammation and more oxidative stress production (Yan, 1997; Obrosova,2002; Jiang, 2004). Increased generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in response to AGEs could occur through multiple mechanisms, for example the ligation of receptor for AGEs (RAGE) and catalase (Ramasamy et al., 2005; Lin et al., 2016). As RAGE is expressed in early embryos (Yan,1997; Wang et al., 2008), AGEs might exert their effects on embryonic development through RAGE or other mecha‐nisms to induce oxidative stress.

The present study sought to determine if exogenous AGE‐modi fied proteins could induce NTDs in mice and, if so, the molecular mechanism underlying this phenomenon.

Materials and Methods

Animals

One hundred and ninety‐two 4—6‐week‐old (40—60 g) spe‐cific pathogen‐free C57BL/6 mice (48 males, 144 females)were obtained from the Animal Center of Xi’an Jiaotong University of China [SCXK (Shaan) 2017‐003]. All exper‐imental procedures were approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of Northwest University of China (Approval No.NWU‐AWC‐20170605M).

Preparation of AGEs

AGE bovine serum albumin (AGE‐BSA) was produced by incubating BSA (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) at a concentration of 50 g/L with 1 M D‐glucose (Sangon Bio, SHH, China) in 0.1 M phosphate‐buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4) at 37°C for up to 8 weeks. Unbound glucose and low molecular weight reac‐tants were removed through dialysis against PBS. AGE‐BSA was lyophilized and resuspended in PBS. The products were quanti fied by measuring optical density (OD) at 405 nm.

Induction of diabetes

Diabetes was induced in 4—6‐week‐old female C57BL/6 mice with 100 mg/kg streptozotocin (Sigma) dissolved in 10 mM sodium citrate (pH 4.5). Normal blood glucose levels were maintained in streptozotocin‐diabetic mice by subcutane‐ously implanting these animals with insulin pellets (Sigma)before pregnancy, until development of hyperglycemia was induced at E4.5 (D group), thereby exposing the embryo to hyperglycemia during the entire post‐implantation period(Li et al., 2005). Mice in the control group were only admin‐istered PBS. Afterwards, female and male mice were placed in the same cage. On the day of copulation, hyperglycemic mice were fed with commercial food containing 0.125% (w/w) vi‐tamin E (VitE) (D/VitE group).

Animal intervention

A total of 192 C57BL/6 mice (48 males, 144 females) were randomly assigned to three groups: an AGE‐BSA group (n=72) consisting of 54 females and 18 males fed with commercial food containing 3% AGE‐BSA, a BSA group (n= 48) consist‐ing of 36 females and 12 males fed with commercial food con‐taining 3% BSA, and a control group (n= 72) consisting of 54 females and 18 males fed with common commercial food.

Four weeks after feeding, the AGE‐BSA group was subdivid‐ed into three subgroups: a D + AGEs group consisting of six females and two males with induced diabetes fed with com‐mercial food after embryonic day 15 (E0.5); an AGE‐BSA/VitE group of six females and two males fed with commercial food containing 0.125% (w/w) VitE; and an AGE‐BSA group with six females and two males fed with commercial food after E0.5.

The BSA group was subdivided into two groups: a BSA/VitE group of six female and two male mice fed with com‐mercial food containing 0.125% (w/w) VitE, and group of six female mice and two male mice fed with commercial food after E0.5.

The control group was subdivided into three groups: a D/VitE group of six females and two males in which diabetes was induced, and whom were fed with commercial food containing 0.125% (w/w) VitE after E0.5; a D group of six females and two males in which diabetes was induced, and whom were fed with commercial food after at E0.5; and a control group of six females and two males fed with com‐mercial food after E0.5.

Male mice in the experiment were used only for breeding and were not ultimately included in the final analysis.

Detection of serum AGEs levels in pregnant mice

Blood samples were collected from the tails of pregnant mice af‐ter 4 weeks of feeding with 3% AGE‐BSA commercial food or 3%BSA commercial food. Blood was centrifuged at 1500 ×gfor 10 minutes. Serum was collected in 1.5‐mL tubes for AGEs as‐say. Determination of AGEs was based on spectro fluorimetric detection modi fied from a previously published method (Ka‐lousova et al., 2002). Brie fly, serum was diluted at 1:50 with PBS (pH 7.4) and fluorescence intensity was measured at the emission maximum (440 nm) upon excitation at 365 nm with a microplate reader (Tecan, Shanghai, China).

Preparation of CML-BSA and N(ε)-(carboxyethyl)lysine (CEL)-BSA

CML‐BSA and CEL‐BSA were prepared as previously de‐scribed (Koito et al., 2004). Briefly, for CML‐BSA, 50 g/L BSA was incubated at 37°C for 24 hours with 45 mM glyox‐ylic acid (Sigma) and 150 mM sodium cyanoborohydride(NaCNBH3) (Sigma) in 2 mL of 0.2 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.4), followed by dialysis against 0.01 M PBS (pH 7.4). For CEL‐BSA, 50 g/L BSA was incubated at 37°C for 24 hours with 45 mM pyruvic acid (Sigma) and 150 mM NaCNBH3 in 2 mL of 0.2 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.4), followed by di‐alysis against 0.01 M PBS (pH 7.4).

Preparation of polyclonal anti-CML-BSA and anti-CEL-BSA antibodies

One mg of each immunogen was emulsi fied in 50% Freund’s complete adjuvant (Boao, Beijing, China) and intradermally injected into rabbits. This was followed by four booster in‐jections of 0.5 mg immunogen in 50% Freund’s incomplete adjuvant (Boao) at 14, 28, and 42 days. Obtained serum was subjected to further affinity puri fication. Antibodies to CML‐BSA and CEL‐BSA were puri fied by affinity chromatography.

Preparation and immunochemical reactivity of embryonic protein

Embryos were collected from mice in each of the five groups(AGE‐BSA, BSA, AGE‐BSA/VitE, BSA/VitE, and control).The tissue was homogenized using a pestle for 20 strokes in lysis buffer and incubated on ice for 20 minutes. Samples were then centrifuged at 880,000 ×gfor 10 minutes. After centrifugation, the supernatant was transferred into a new tube. Protein concentration was measured using a Bradford assay. Each well was coated with mouse embryonic proteins(10 μg/mL) and then blocked with 1% non‐fat milk. Follow‐ing three washes with PBS containing Tween‐20, each well was incubated with purified mouse polyclonal anti‐CML and ‐CEL antibodies (1:4000) and washed three times.Horseradish peroxidase‐conjugated anti‐rabbit IgG (1:3000;Sangon, Shanghai, China) was added and incubated for 1 hour at 37°C. After washing three times, TMP solution was added and OD values were measured at 490 nm with a mi‐croplate reader (Tecan, Shanghai, China).

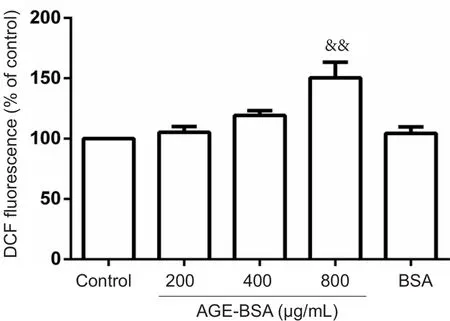

Preparation of embryonic cell suspensions and assessment of intracellular ROS production

E8.5 embryos were dissected from uteri in PBS, and extraem‐bryonic structures were placed in Dulbecco’s Modi fied Eagle’s Medium (DMEM). Whole embryos were minced and passed through a cell strainer with 40‐μM nylon mesh (BD Falcon‐TM, Shanghai, China), to generate single‐cell suspensions. The suspension was prepared at a density of 2 × 107cells/mL. Em‐bryonic cells were cultured in DMEM under a range of AGE‐BSA concentrations for 24 hours: 0, 200, 400, and 800 μg/mL in DMEM. Cells were subsequently washed twice with PBS.Intracellular ROS production was measured with 2′,7′‐dichlo‐rodihydro fluorescein diacetate (DCF‐DA) (Molecular Probes,Shanghai, China). Embryonic cells were incubated with DCF‐DA (5 μM) in serum‐free medium at 37°C for 30 minutes and then washed with PBS. DCF fluorescence was excited at 488 nm, and emission at 530 nm was measured on a Gemini EM Reader (Molecular Devices, Shanghai, China). Fluorescence intensity values are presented as the percentage of control val‐ues after subtraction of background fluorescence.

Measurement of malondialdehyde (MDA) and H2O2

E7.5 embryos were collected for to assay MDA and H2O2.MDA was assayed using an ultraviolet‐visible spectropho‐tometer and photometer (Agilent, Beijing China) using the thiobarbituric acid test (Ohya et al., 1993). H2O2was assayed using a kit from Cayman Chemicals (Shanghai, China)according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Results were normalized to protein concentrations in cell extracts.

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as the mean ± SD and were analyzed by SPSS software (SPSS 19.0, IBM, Armonk, NY). One‐way anal‐ysis of variance followed by a least signi ficant difference test was used to examine differences between treatment groups.Pvalues less than 0.05 were considered statistically signi ficant.

Results

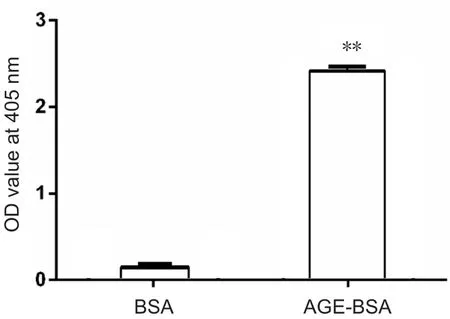

Veri fication of AGE-BSA

The OD at 405 nm of AGE‐BSA gradually increased from 0 to 2.4, while that of control BSA prepared under the same conditions without glucose was lower than 0.15 (Figure 1).

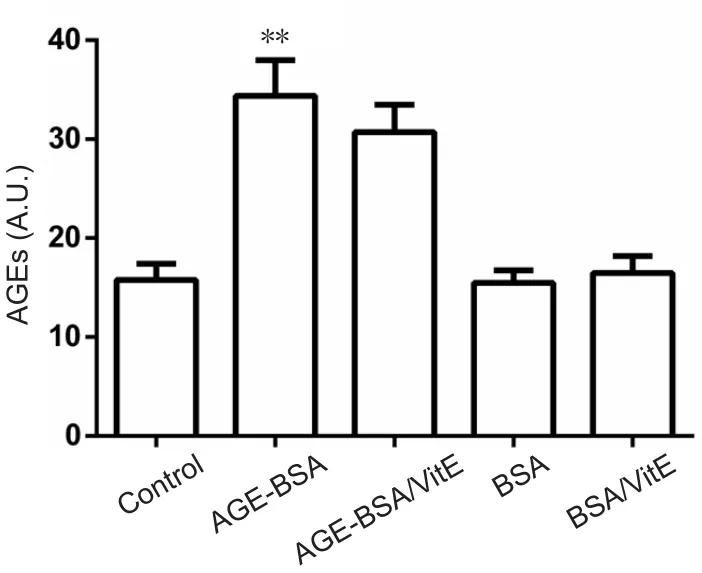

Serum AGEs level in AGE-BSA feeding pregnant mice

Serum levels of AGEs increased significantly (P< 0.01) in AGE‐BSA pregnant mice compared with BSA control preg‐nant mice. VitE supplementation did not affect levels of AGEs in AGE‐BSA or BSA control pregnant mice (P> 0.05; Figure 2).

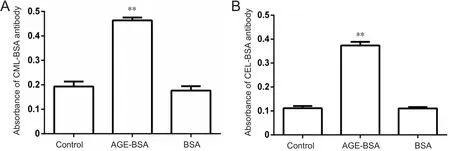

Immunochemical reactivity of embryonic proteins

Reactivity of CML‐BSA and CEL‐BSA antibodies, which recognize embryonic proteins, increased significantly in embryos of AGE‐BSA mice compared with control mice and BSA mice, indicating that mice fed with AGE‐BSA food could increase embryonic CEL and CML contents (P< 0.01;Figure 3). VitE supplementation did not change embryo protein reactivity to CML and CEL (data not shown).

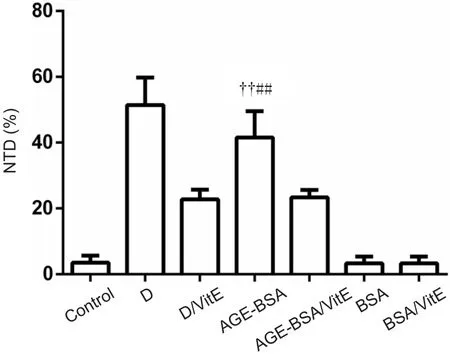

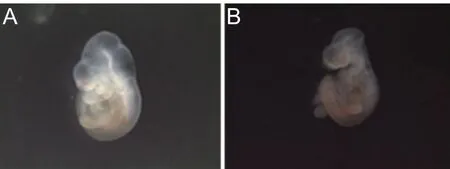

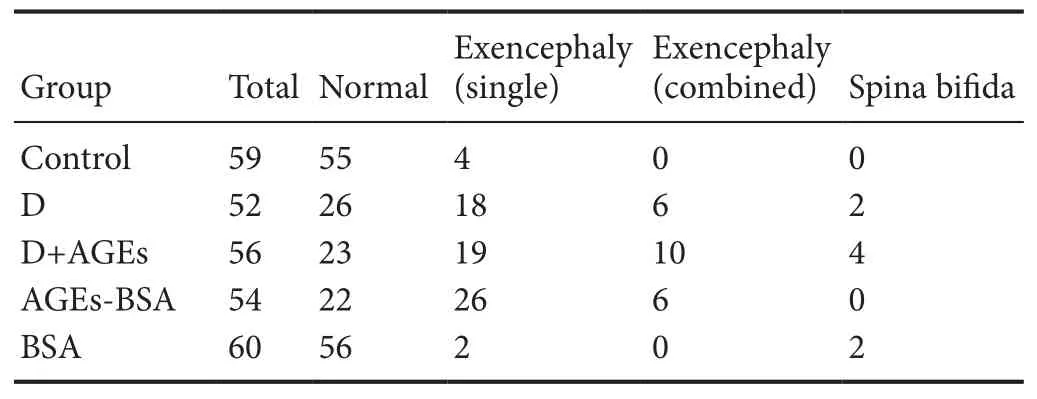

AGE-BSA induces NTDs in mice in vivo

As shown in Figure 4, the incidence of NTDs was signifi‐cantly increased in AGE‐BSA mice at E10.5, similar to the effect of hyperglycemia (Figure 5). Incidence of NTDs was also signi ficantly increased in diabetic AGE‐BSA mice com‐pared with diabetic mice or AGE‐BSA mice (P< 0.05). In contrast, there was no effect of BSA or saline control admin‐istration on embryonic developmental malformation. The increased incidence of NTDs induced by AGE‐BSA admin‐istration in mice could be partially blocked by VitE supple‐mentation (Figure 4 & Table 1).

Serum levels of MDA and H2O2 in embryos of mice fed with AGE-BSA

Figure 1 Optical density (OD) value at 405 nm of advanced glycation end product bovine serum albumin (AGE-BSA) and bovine serum albumin (BSA) control at the end of the 8-week incubation.

Figure 2 Serum levels of AGEs in mice fed with AGE-BSA or BSA.

Figure 3 Immunochemical reactivity of antibody against CML-BSA (A) and CEL-BSA (B) with embryo proteins.

Figure 4 Effects of AGE-BSA on incidence of NTDs in C57BL/6 mice.

Figure 5 Embryos with normal neural tube formation and neural tube defects.

Table 1 Morphology of embryonic day 10.5 mouse embryos from different groups

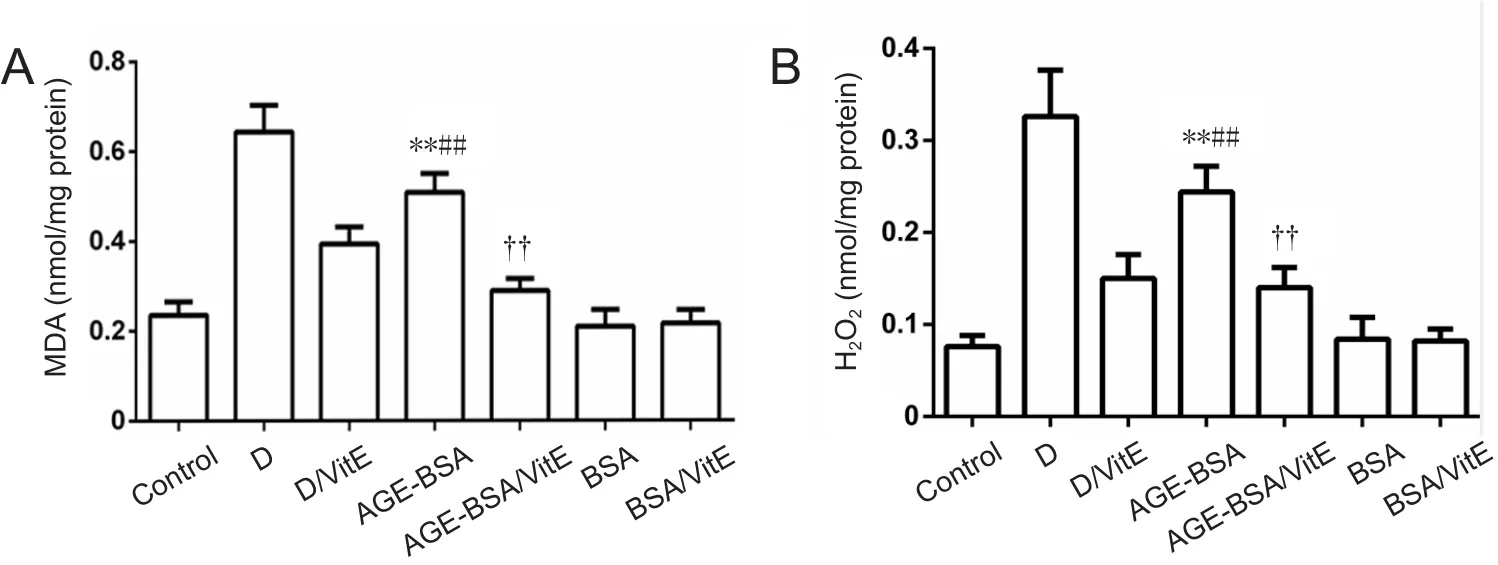

Figure 6 MDA and H2O2 levels in AGE-BSA and control mice with different treatments.

Figure 7 Effects of AGE-BSA on reactive oxygen species production in embryonic cells on embryonic day 8.5 (E8.5).

To further test whether increased incidence of NTDs is the re‐sult of oxidative stress induced by AGE‐BSA, oxidative stress markers MDA and H2O2were assayed in embryos. Signi ficant increases in MDA levels (P< 0.01; Figure 6) and H2O2(P<0.01) were observed in embryos of AGE‐BSA mice compared with BSA control mice. Moreover, MDA and H2O2levels were signi ficantly higher in diabetic AGE‐BSA mice compared with diabetic mice or AGE‐BSA mice. VitE signi ficantly decreased MDA and H2O2levels (P< 0.01) in embryos of AGE‐BSA mice compared with BSA control mice (Figure 6).

Intracellular ROS in embryonic cells

In situROS production by embryonic cells at E8.5, as mea‐sured by DCF fluorescence, indicated signi ficantly increased ROS levels after 24‐hour incubation with 800 μg/mL AGE‐BSA. Intracellular ROS production increased by 150.40 ±29.17% in embryonic cells cultured in 800 μg/mL AGE‐BSA medium compared with control cells cultured in 800 μg/mL BSA medium (100%;P< 0.01; Figure 7).

Discussion

Contributions and limitations of previous studies

AGEs, a heterogenous group of molecules formed by the nonenzymatic reaction of glucose with protein, are critical pathogenic mediators of diabetes complications and other associated diseases such as aging, atherosclerosis, and Alz‐heimer’s disease. The formation of AGEs occurs at a con‐stant and slow rate in normal conditions, but is markedly accelerated in hyperglycemia because of increased availabil‐ity of glucose, and signi ficantly increased by eating habits or lifestyle choices such as smoking. However, the role of AGEs in embryonic development has remained in question.

Preparation of AGE‐BSA by incubation of BSA and glu‐cosein vitrohas been widely used to mimic the effects of AGEs (Schmidt et al., 1995). By incubating BSA and glucosein vitrofor 8 weeks, an AGE‐BSA mixture including inter‐mediate and late AGEs is produced (Schmidt et al., 1995;Alam et al., 2016; Koch et al., 2017; Pietsch et al., 2017).AGE‐speci fic fluorescence, which has been described in sev‐eral publications (Monnier, 1981; Lo, 1994; Leclere, 2001),is widely used to detect AGEsin vivoandin vitro(Nagai,2000; Valencia et al., 2004). One study showed that fluores‐cence detected at an excitation/emission of 365/440 nm is a good choice for glucose‐modi fied human serum albumin(Schmitt et al., 2005). Indeed, 365/440 nm has been proven to be a very effective wavelength to detect speci fic AGEs in blood and tissue samples (Kalousova, 2002; Jing et al., 2009;Bohlooli et al., 2013). As such, 365/440 nm was used in this study to detect AGEs levels in mouse blood.

Apart from endogenous AGE formation, AGEs are also absorbed by the body from exogenous sources including cigarette smoke and highly heated processed foods, which contain high amounts of AGEs (Stirban and Tschöpe, 2015).Kinetic studies indicated that 10—30% of dietary AGEs consumed are intestinally absorbed. Thus, plasma concen‐trations of AGEs appear to be directly in fluenced by dietary AGE intake and the body’s capacity for AGE elimination.

Distinguishing characteristics of the current study

In the present study, AGE‐BSA was fed to mice to exam‐ine the effect of AGEs (Peppa et al., 2003; Chen et al., 2013).The results showed that serum levels of AGEs significantly increased in AGE‐BSA mice compared with BSA control mice. Moreover, CML‐BSA and CEL‐BSA reactivity were remarkably increased in the embryos of AGE‐BSA mice com‐pared with control mice, indicating increased CEL and CML contents in embryos of mice fed with AGE‐BSA food. Thus,feeding is a suitable method to administer AGEs to animals.

The results of this study demonstrated a signi ficantly higher incidence of NTDs in AGE‐BSA mice compared with control mice. In addition, a higher incidence of NTDs was observed in diabetic AGE‐BSA mice compared with diabetic mice. This result is consistent with previous results indicating that AGEs is a risk factor for induction of NTDs in the absence of hyper‐glycemia (Carmichael, 2003; Suarez et al., 2012). As food is the major source of exogenous AGEs, it is reasonable to conclude that lifestyle, especially eating behaviors, could be an import‐ant factor for pregnant women. Notably, VitE supplementa‐tion could inhibit the increased incidence of NTDs caused by AGE‐BSA compared with the non‐VitE group, similar to its effect on diabetic mice. Therefore, the mechanism underlying the teratogenic effect of AGE‐BSA on embryonic development may be similar to the mechanism induced by diabetes, at least with regard to increased oxidative stress.

While overproduction of oxidative stress is associated with embryonic dysmorphology in diabetic pregnancy, ad‐ministration of antioxidants could attenuate this teratogenic effect in embryos subjected to a hyperglycemic environment bothin vivoandin vitro(Loeken, 2005). For non‐diabetic pregnant women, oxidative stress may also be a risk factor for inducing embryonic malformation. First, a high level of free radicals can directly damage DNA or inhibit Pax3 expression, which is crucial for neural tube development.Second, oxidative stress caused by AGE‐RAGE interaction is the major mechanism underlying the biological effect of AGE. Although we did not observe significantly different serum MDA levels between NTDs‐affected and unaffected control pregnant women in the presence of different AGEs levels (Li et al., 2014), we found signi ficantly different MDA levels in embryos between AGE‐BSA and control mice. One explanation for this is that the materials used to assay MDA were different: one is for human serum, while the animal experiment assayed MDA levels of whole embryos. Second,as the background, diet, and other lifestyle habits of mice are identical, it is easy to observe the effect of AGEs on MDA levels to the exclusion of other factors. In contrast, many factors vary between individual humans, including different eating habits. Furthermore, we observed that the antioxi‐dant VitE could decrease the incidence of NTDs caused by AGE‐BSA feeding but could not totally block the teratogenic effect. Thus, increased oxidative stress is unlikely to be the only mechanism by which AGEs induce NTDs.

Limitations

The results of this study clearly indicated that AGE‐BSA could induce NTDs in embryonic mice, at least in part by elevating oxidative stress levels. However, this mechanism is not necessarily the only cause of NTDs. Further studies will be important to demonstrate the detailed localization of CML and CEL in pathological embryonic tissues with speci fic antibodies, as well as changes in signaling pathways downstream of the oxidative stress caused by AGEs.

Signi ficance

In conclusion, exogenous application of AGE‐BSA to C57BL/6 mice resulted in an increased incidence of NTDs in the absence of hyperglycemia, thus replicating the effects of maternal diabetes on embryonic development. These find‐ings both con firm and provide a new mechanistic basis for the role of AGEs in NTDs occurring in nondiabetic preg‐nancies and NTDs caused by maternal diabetes.

Author contributions:RLL designed this study and wrote the paper. WWZ performed experiments. WWZ and BYG analyzed data. All authors approved the final version of the paper.

Conflicts of interest:The authors declare that there is no duality of interest associated with this manuscript.

Financial support:This work was supported by the grant from Shaanxi Technology Committee of China, No. 2013JM4001, and the China Scholarship Council for Ru-Lin Li. Funders had no involvement in the study design;data collection, analysis, and interpretation; paper writing; or decision to submit the papaer for publication.

Institutional review board statement:The procedures were in accordance with ethical standards of the Animal Ethics Committee of Northwest University of China (approval No. NWU-AWC-20170605M).

Reporting statement:This study follows the Recommendations for the Conduct, Reporting, Editing and Publication of Scholarly Work in Medical Journals developed by the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors.

Biostatistics statement:The statistical methods of this study were reviewed by the biostatistician of Laboratory for Development, College of Life Sciences,Northwest University, China.

Copyright license agreement:The Copyright License Agreement has been signed by all authors before publication.

Data sharing statement:Datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Plagiarism check:Checked twice by iThenticate.

Peer review:Externally peer reviewed.

Open access statement:This is an open access journal, and articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as appropriate credit is given and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

- 中国神经再生研究(英文版)的其它文章

- In Memoriam: Ray Grill (1966–2018)

- Reorganization of injured anterior cingulums in a hemorrhagic stroke patient

- A novel chronic nerve compression model in the rat

- Analgesic effect of AG490, a Janus kinase inhibitor, on oxaliplatin-induced acute neuropathic pain

- Three-dimensional visualization of the functional fascicular groups of a long-segment peripheral nerve

- Novel conductive polypyrrole/silk fibroin scaffold for neural tissue repair