Stem cell therapy for retinal ganglion cell degeneration

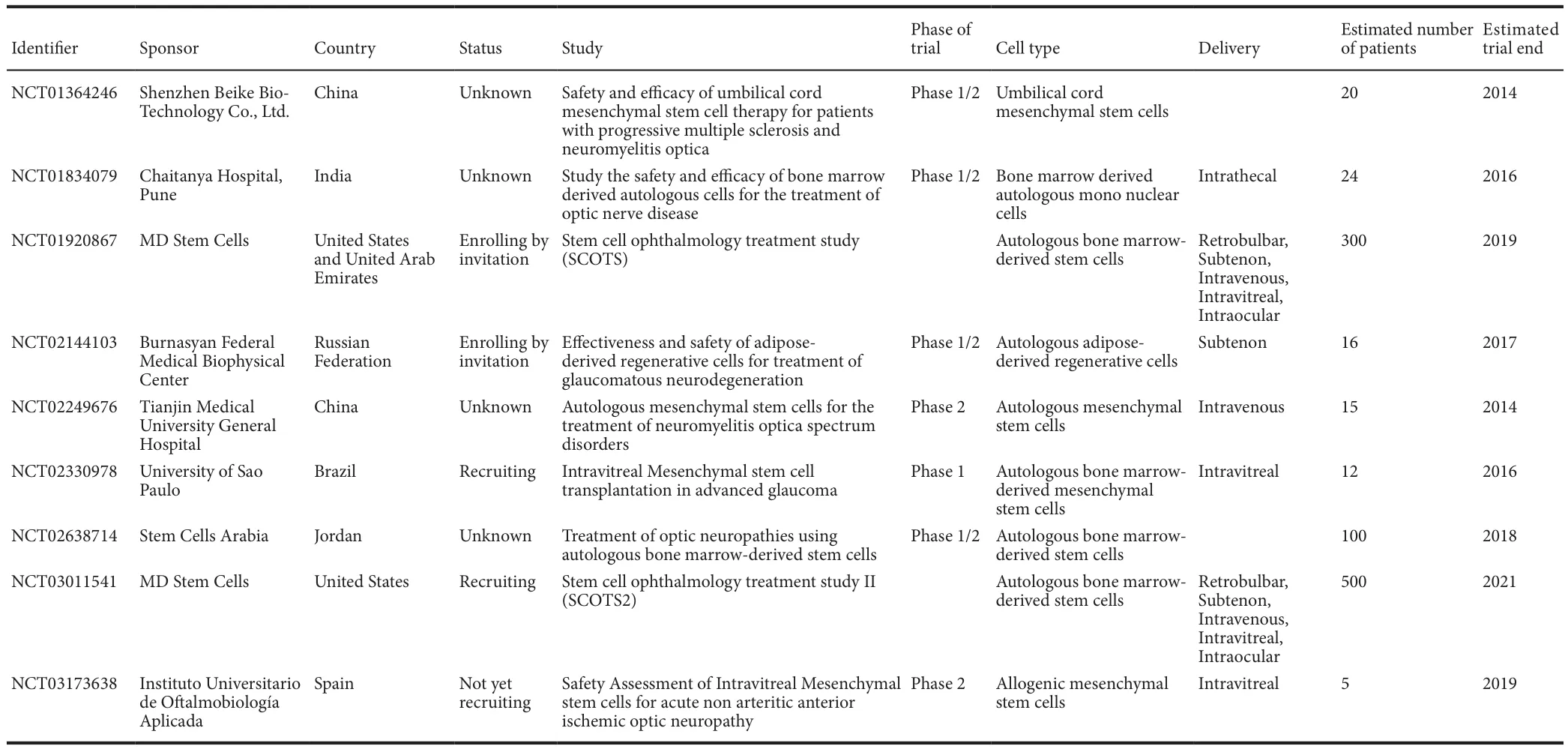

The prospects of stem cell therapy for retinal ganglion cell (RGC)degeneration in human:RGC degeneration is a common pathologic cause of glaucoma and optic neuropathies, which are the leading cause of irreversible blindness and visual impairment in developed coun‐tries, currently affecting more than 100 million people worldwide. In‐traocular pressure lowering can slow down glaucoma progression in a proportion of patients. Also, there is still no effective therapy for optic neuropathies. Besides, the degenerated RGCs in glaucoma cannot be repaired, and human retina has limited regenerative potential. There‐fore, the development of new therapeutic treatments against RGC degeneration is needed. Cell replacement and neuroprotection are the principle strategies for glaucoma and optic neuropathy treatment.Replacing the diseased or degenerated cells by stem cell‐derived RGCs should provide effective therapeutic treatment. However, complex cir‐cuitry in the retina makes cell replacement challenging and difficult for functional repair. Alternatively, neuroprotection is more realistic and applicable to preserve the patients’ vision. Numerous neuroprotection strategies have been investigated, including peripheral nerve grafting,electrical stimulation, application of neurotrophic factors (brain‐de‐rived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), ciliary neurotrophic factor (CNTF),glial cell‐derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) and nerve growth factor(NGF), direct intrinsic regeneration stimulation, RNA interference and human adult stem cells. Our group recently reported that the in‐travitreal transplantation of human periodontal ligament‐derived stem cells (PDLSCs) ameliorates RGC degeneration after optic nerve injury in rats and promotes neural repair by enhancing axon regeneration through cell‐cell interaction and neurotrophic factor secretion from PDLSCs (Cen et al., 2018). At present, there are 9 clinical trials on human adult stem cells for glaucoma and optic nerve diseases (www.clinicaltrials.gov/; Table 1). An emerging role of human adult stem cell therapy for glaucoma and optic neuropathy treatments is foreseeable in the near future.

Human adult stem cells for RGC protection:Adult stem cells are the quiescent undifferentiated cells found in fully developed tissues with the abilities to self‐renew and differentiate into mature cells.Adult stem cells can be conveniently isolated from accessible tissues,including bone marrow, peripheral blood, adipose tissues and teeth.Different types of adult stem cells can be identi fied according to their lineages, such as hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs), mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) and neural stem cells. Although adult stem cells function to maintain the adult tissue homeostasis by cell replacement and tissue regeneration, they can also modulate the microenvironment in the host tissue and protect the RGCs from degeneration.

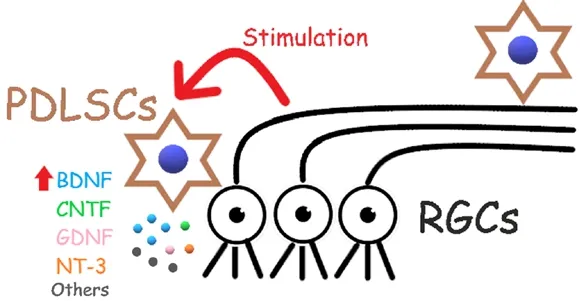

The neuroprotective effect of adult stem cells for RGC degenera‐tion has been mainly studied in MSCs. There is no reported study on RGC protection by HSCs. Different sources of MSCs, including rat and mouse bone marrow, adipose tissue, human chorionic plate and rat dental pulp, have been shown to enhance RGC survival after optic nerve injury (Mead et al., 2013; Chung et al., 2016; Hu et al., 2017; Li et al., 2018). The mechanisms of MSC neuroprotection can be mod‐ulating the plasticity of damaged host tissues, secreting neurotrophic and survival‐promoting growth factors, restoring synaptic transmitter release, integrating into existing neural and synaptic networks, and re‐establishing functional afferent and efferent connections (Ng et al.,2014). In a secretome study, 25 secreted proteins were identi fied from human bone marrow‐derived MSCs (Johnson et al., 2014), among which interferon‐γ, interleukin (IL)‐11, leukemia inhibitory factor, IL‐6, BDNF, platelet derived growth factor AA (PDGF‐AA) and PDGF‐AB/BB are enriched in human bone marrow‐derived MSCs compared to human adult dermal fibroblasts. Moreover, secretion of NGF, BDNF and neurotrophin‐3 (NT‐3) was reported in rat dental pulp‐derived stem cells (Mead et al., 2013). BDNF and GDNF are important regula‐tors in neuroprotection of mouse bone marrow‐derived MSCs (Hu et al., 2017). In our study, we found that human PDLSCs after intravitreal transplantation can survive and migrate to the RGC layer and even to the optic nerve (Cen et al., 2018). The cell‐cell interaction is a critical condition to protect RGCs from degeneration since RGC survival is increased in the contact fashion of human PDLSC‐retinal explant co‐culture. In addition, human PDLSCs highly express BDNF, CNTF,GDNF and NT‐3, which are the essential neurotrophic factors to en‐hance RGC survival and axon regeneration. Notably, we discovered a novel mechanism of human adult stem cells that the injured retina enhances BDNF secretion from human PDLSCs (Figure 1). How this positive feedback stimulated by the host retinal injury enhances BDNF secretion from human PDLSCs and what factors and retinal cell types are involved in this stimulation require further investigations. Besides,human PDLSC transplantation induces mild in flammation in rats, and in flammation has been reported to promote neural survival and axon regeneration in return. Whether the induction of mild in flammation by the xeno‐transplantation contributes to the increased RGC survival and axon regeneration remains to be delineated. Nevertheless, resultsof our human PDLSCs study and other reported studies indicate a po‐tential clinical application of MSCs for glaucoma and optic neuropathy treatment in future.

Table 1 Registered adult stem cell-based clinical trials for glaucoma and optic nerve diseases

Figure 1 The retinal ganglion cell (RGC) protective mechanisms of human periodontal ligament-derived stem cells (PDLSCs).

Human adult stem cells for RGC regeneration:The basis of cell re‐placement therapy is that new RGCs could be regenerated from stem cells to substitute the damaged RGCs in glaucoma or optic neuropa‐thies. Pluripotent stem cells, including embryonic stem cells (ESCs)and induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), have been studied for their differentiation potential into retinal lineages (Eiraku et al., 2011).Although adult stem cells are believed to be tissue‐specific and only possess restricted differentiation capability, increasing number of stud‐ies report that adult stem cells are capable of giving rise to cells to an entirely distinct lineage. Our group have previously demonstrated that human PDLSCs can be induced to retinal lineage (Huang et al., 2013)and generate electrically functional RGC‐like cells (Ng et al., 2015). No‐tably, pluripotent sub‐population can be found in human PDLSCs (Pe‐laez et al., 2013). These pluripotent adult stem cells are the neural crest stem cells residing in neural crest‐derived adult tissues. They can form teratomas in the immunode ficient mice with tissues from the three em‐bryological germ layers (endoderm, mesoderm, and ectoderm), and can be induced into neuronal lineage, implying that pluripotent adult stem cells can be isolated and enriched from human adult tissues without the necessity of reprogramming. The efficiency of RGC production can be enhanced with the use of pluripotent adult stem cells. Adult stem cells,in addition to the ESCs and iPSCs, can also be used to produce RGCs for glaucoma and optic neuropathy treatments. Nevertheless, the re‐placement therapy based on exogenous stem cell‐derived RGCs remains challenging because of the complex circuitry of the inner retina and the precise axonal projection to brain targets.

Another possible strategy for RGC regeneration is the endogenous regeneration by retinal stem cells. Unlike the limbal stem cells for cor‐neal epithelium regeneration, retinal stem/progenitor cells are hardly identi fied in adult high‐order mammalian retina. In contrast, Müller glia can be transiently reprogrammed into retinal progenitor stage for endogenous regeneration through de‐differentiation and re‐differenti‐ation. However, the endogenous activation of Müller glia is extremely low under normal circumstances. Müller glia reprogramming can be enhanced by retinal damage and induction of Wnt/β‐catenin signal‐ling. The reprogrammed Müller glia can be stably maintained by fusion with exogenously transplanted or endogenous adult stem cells through cell‐hybrid formation (Sanges et al., 2013). The reprogrammed Müller glia can proliferate and differentiate into RGCs and amacrine cells in the N‐methyl‐D‐aspartic acid‐treated mouse retina. Further work is needed to determine the treatment efficacy in other RGC degeneration models and to re fine the differentiation signals for speci fic RGC regen‐eration from the de‐differentiated Müller gliain vivo.

Conclusion and future perspective:Endogenous regeneration by retinal stem cells is the best regimen for RGC replacement against the RGC degenerative diseases. However, due to their limited availabil‐ity, stem cell‐based treatment relies on exogenous stem cell sources.Among different types of stem cells, MSCs are excellent for transplan‐tation since they possess strong immunosuppressive properties and inhibit the release of pro‐in flammatory cytokines, allowing autologous as well as allogeneic transplantation without the need of pharmaco‐logical immunosuppression. Moreover, MSCs can be transplanted directly without genetic modi fication or pre‐treatments, and are able to migrate to the tissue injury sites without the concern of teratoma formation after transplantation. No moral objection or ethical con‐troversies involved in their attainment. Importantly, MSCs can be directly applied for neuroprotection, and they can also be induced to neuronal cells for replacement therapy. These biological properties and the expansion potential of MSCs provide the therapeutic applica‐tions of MSCs to treat different human diseases, especially the RGC degenerative diseases. Yet, there are queries and uncertainties. Which MSC sources and types are optimal for neuroprotection? Can the neu‐roprotective effect of MSCs be modulated and enhanced? What is the optimal cell number and stage for transplantation? Which transplan‐tation route is suitable for each individual optic neuropathy? Further research is needed to optimize and standardize the stem cell treatment effect before the routine clinical application of stem cell therapy for RGC degenerative diseases.

This work was supported in part by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81570849 and 81470636), Research Fund for the Doctoral Program of Higher Education of China (20114402120007) and Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province (2015A030313446), China.

Ling-Ping Cen, Tsz Kin Ng*Joint Shantou International Eye Center of Shantou University and The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shantou, Guangdong Province, China(Cen LP, Ng TK)Shantou University Medical College, Shantou, Guangdong, China;Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, China (Ng TK)

*Correspondence to:Tsz Kin Ng, Ph.D., micntk@hotmail.com.

orcid:0000-0001-7863-7229 (Tsz Kin Ng)

Accepted:2018-05-25

doi:10.4103/1673-5374.235237

Copyright license agreement:The Copyright License Agreement has been signed by all authors before publication.

Plagiarism check:Checked twice by iThenticate.

Peer review:Externally peer reviewed.

Open access statement:This is an open access journal, and articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share-Alike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as appropriate credit is given and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

Open peer reviewer:Arne M. Nystuen, University of Nebraska Medical Center,USA.

- 中国神经再生研究(英文版)的其它文章

- In Memoriam: Ray Grill (1966–2018)

- Reorganization of injured anterior cingulums in a hemorrhagic stroke patient

- A novel chronic nerve compression model in the rat

- Analgesic effect of AG490, a Janus kinase inhibitor, on oxaliplatin-induced acute neuropathic pain

- Three-dimensional visualization of the functional fascicular groups of a long-segment peripheral nerve

- Novel conductive polypyrrole/silk fibroin scaffold for neural tissue repair