关于城市设计能否帮助高密度城市提供可负担住宅的探究—印度孟买的三种空间策略范式

关成贺 拉胡尔·梅赫罗特拉

1 简介:低收入家庭和城市移民

来自贫困地区的人们通常会选择搬到经济充满活力的城市寻找就业机会。从20世纪初美国工业城市装配线上的工人到20世纪末中国沿海城市大量的农民工,城市移民们不仅被更高的工资所吸引,而且更加接近了很多不属于他们的社会福利。然而,高密度城市中的城市移民往往会发现自己处于最不利的环境中[1]。为了改善城市贫困人口的基本生活条件,联合国人居署提出了一系列的战略。例如,提供可负担的社会住宅,通过提供基本的公民服务来提升基础设施(联合国城市主题),并通过教育和培训的方式来进行介入。实施这些计划的挑战在于,如何通过城市设计更好地促进经济可行性、社会公正和环境友好的战略的达成。

本文的组织结构如下:在第2节将对孟买的空间转变历程进行一个回溯。第3节将讨论在孟买应用高层、中层、低层3种类型的城市设计介入策略来解决低收入移民和城市贫困家庭居住问题的区别。第4节将揭示连接不同类型“可负担住宅”的空间逻辑,并提出一个面向高密度城市的更加可持续的混合反应设计策略。

2 孟买的城市空间转变与城市设计介入

这篇文章所关注的孟买是一个贫民窟居民数量庞大且不同社会阶层之间的土地使用权关系非常紧张的城市,这一切都为新型的居者有其屋(可负担住宅)战略带来不小的挑战。2016年,印度马哈拉施特拉邦负责基础设施建设的政府机构—孟买大都会区发展管理局(MMRDA)提出了一个2036年的孟买区域规划建设方案。在这个计划中,孟买将建设新的城市中心、新的城市道路和一座新机场。如果实施,孟买的城市空间结构将从单一中心转变为多中心。因此,某些土地使用类型将被重新分配到城市的外围。在此过程中,经济适用房(可负担住宅)应该被仔细地考量并与其他城市功能有机结合。谁将被重新安置?哪些社会阶层将继续留在已经过度拥挤的中心城市?这些问题都值得深思。

图1展示了孟买低收入居住区的空间分布情况,预计有超过1,000多万的人牵扯其中。许多机构都试图解决孟买大都市区的非正式住区、低收入住房和城市贫民窟的问题。我们将这些方式方法概括总结为3种城市设计干预的范式。

3 三种为低收入人群提供经济适用房的城市设计范式

对于城市贫民来说,并没有一个普适性的解决方案。我们必须意识到每个项目都有其独特性。我们将通过空间形态和建筑类型的维度来对它们进行分类。

3.1 高层建筑类型方法:城市升级

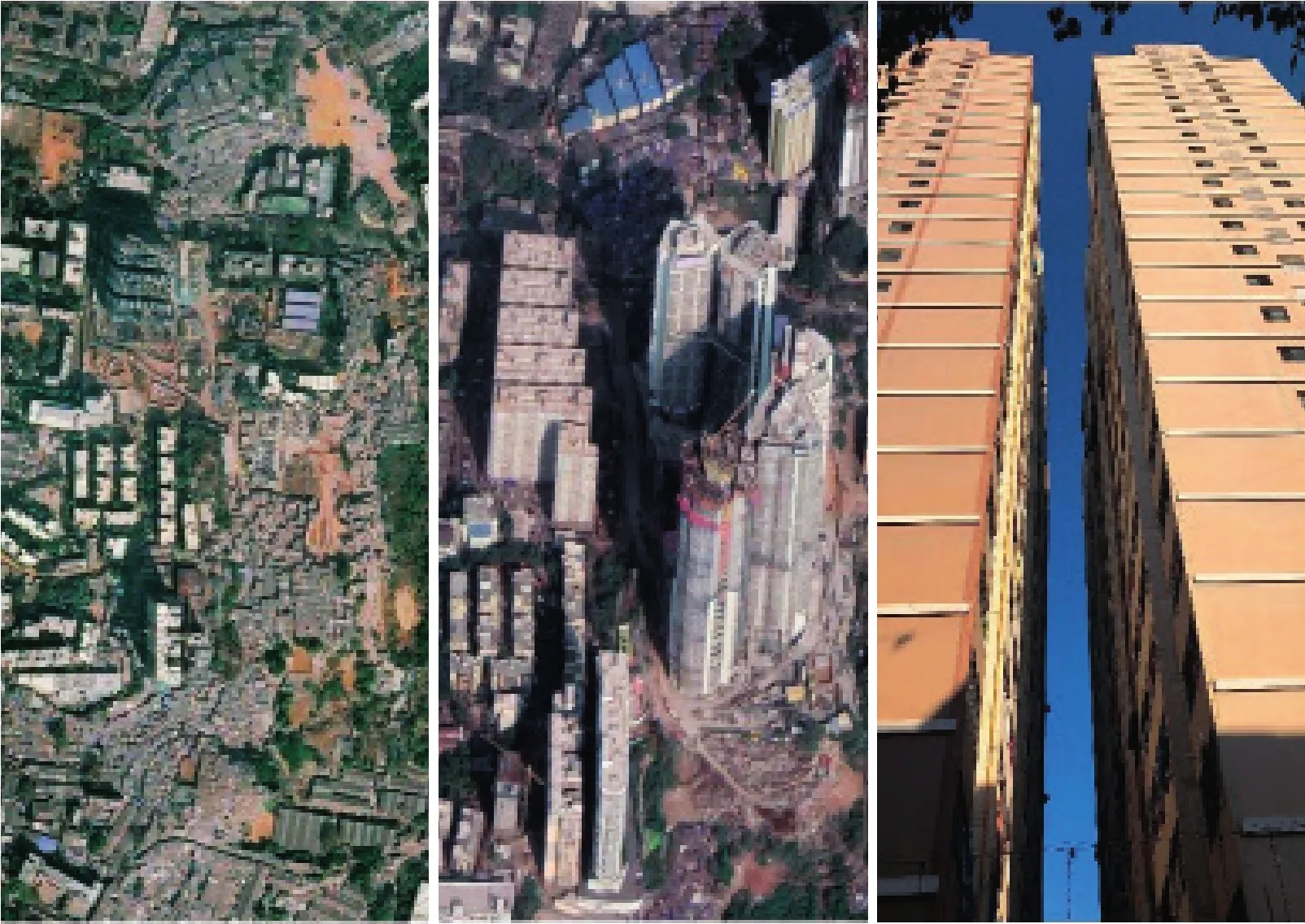

为了应对经济适用房的旺盛需求,一种方法是开发高层建筑,从而最大限度地提高住房供应量并达到更高的容积率。这一概念与20世纪设计先锋们提出的著名方案没有太大区别:增加紧凑型,最大化容积率的同时最小化建筑占地面积。通过这样做,我们可以为高密度城市提供更多的开放空间。这一做法受到了那些想把孟买提升为全球化都市的人群的欢迎。对他们而言,孟买需要用高层建筑来创造一个更“引人注目的全球化身份”,而高层建筑群也是全球化城市倡议[2]提出的全球化都市的十大特征之一。这一想法同时得到了政策制定者的支持,他们认为这是孟买加速城市化进程的一个重要机会。他们着迷于上海或纽约等现代都市的天际线[3]。过去几十年里上海的天际线发生的重大变化也为重新开发诸如帕雷尔在内的老工业区注入了强大的信心。图2显示了在帕雷尔被当地人称为古尔冈(新德里的卫星城)的厂区聚落的空间转换。在2000年,纺织工厂仍然在整个城市肌理中占据主导地位。

到了2009年,在铁路沿线的西部地区我们可以观测到,随着纺织厂的拆除,新建筑也开始修建。而到2018年,高层塔楼完全代替了工厂,主导了该地区的主要城市特征。图3描绘了帕雷尔的天际线,它俨然已经是一个现代化的都市,虽然高层聚居区前依然存在着一些与铁路相关的租赁用途建筑。孟买已经拥有超过一百多座的高层建筑,而且还有更多的建筑在建设中。似乎一个全球化都市已然成型。然而,随之而来的是中高收入群体的住房供应显著增加,而保障房的供应仍然非常不足[4],造成这种住房供应的差异是什么原因呢?

图3 / Figure 3帕雷尔的天际线,孟买,2018The skyline of Parel, Mumbai, in 2018

图4 / Figure 4位于孟买的一个城市社区帕雷尔的贫民窟安置住房。该地区曾是工厂区,现在取而代之的是新的办公区与住宅开发项目Slum resettlement housing in Parel, an urban neighborhood of Mumbai. The area was used to populated with mill factories, which are now replaced by new of fi ce and residential developments

我们需要仔细研究一下帕雷尔的一个具体项目。该项目旨在重新开发拉贾斯坦邦舍屋瑞的城市贫民窟和新的政策路线。图4中左侧图片显示,现有的城市结构(主要是城市贫民窟)正在被高层建筑所取代。当政府与开发商采用公共私人合伙企业(P3)模式运营时,目的是为了更有效地推进再开发。而政府和开发商之间的谈判结果是,让开发商在为贫民窟居民提供负担得起的住房,同时有权建造豪华的价格昂贵的独立产权公寓。开发商将有义务提供服务以维持经济适用房基本的运营,同时前5年不收取任何费用。图4中的中间图像提供了一个鸟瞰视角,在6幢经济适用房的旁边矗立着5座楼层更高的豪华公寓大楼。该项目提供的豪华公寓面积要比经济适用房还多。此外,在建的这些保障性住房中,许多住房已经或即将被废弃。为什么城市贫民要离开保障房,即使没有收取他们任何费用,他们又将去哪儿呢?

“他们只是搬回了贫民窟”,一个来自当地研究结构—城市设计研究院(UDRI)的城市学者解释到:“不是因为贫民窟更好,而是他们所居住的高层建筑已经不再适合居住了。”确实,5年后(可以更短或更久,取决于合同),开发商不再负责维护这些建筑。当电梯停止工作后,有许多老年人被困在高层建筑的楼上。没有政府的帮助,他们只能靠自己。当我们走访这些建筑时,一群正在漫长而黑暗的走廊里玩迷你板球游戏的年轻人吸引了我们的眼球。根据他们的说法,当供水停止时,老年人只能依靠他们来运送桶装水维生。很难想象他们在被切断了基本的生活供应后,是如何在20层的高楼里幸存下来。最终他们只能搬出去。

短短几年后,如此高比例的贫困居民逃离高层经济适用房,这是社会网络崩溃的结果。城市移民在很大程度上依赖于他们在家乡的社会关系来寻找工作,这也是为什么他们在到达孟买时往往会和他们的同胞聚集在一起的原因。但是一旦他们重新被安置到高层建筑中,他们原本的社会关系就会消失,随之而来的生计也会消失。目前的高层经济适用房并不能为城市贫民提供一个可持续的解决方案,除非同时能让他们获得谋生机会。

这种高层类型学的居住解决方案也加剧了交通堵塞。当这种模式大规模地向社区推广时,会有非常多相似规模的项目同时开建。然而至少在可见的未来,并没有更新道路系统或者增加公共交通运力的计划,但居住密度已经翻了一翻。此外,新增豪宅的居民是那些买得起私人汽车的富人。这一切将使现有的交通流量过载并极大减少可达性。最后,高层建筑多带来的空间布局并不能提供一个令人愉快的居住环境。在图4中,右侧的图像显示了两个住宅楼之间的狭窄空间。在“居者有其屋”运动已经推出金融解决方案的当下,空间设计应该更多地强调公共卫生、公共安全以及自然光照和清洁水源的基本权利。

图5 / Figure 5在孟买实施的住房政策 / Housing policies implemented in Mumbai

图6 / Figure 6达拉维贫民窟清理项目 / Slum clearance project in Dharavi

总而言之,高层的保障房并不能为城市贫民提供一个令人满意而有效的居住解决方案。高层类型学的居住解决方案增加了交通压力;与此同时,没有足够的基础设施来容纳更多的机动车。竖向发展城市的本意是为了最大化利用土地且使孟买升级成为一个更具吸引力的全球化都市。然而,高层保障房计划的实施既不能以适当的方式容纳城市贫民,并且不能长期支持他们。一系列的干预措施,应当在孟买分配其资源,尤其是土地资源之前就已经完成,这样孟买才有可能把其天际线打造成世界级城市的水准。其中,城市设计的干预策略可以借鉴学习先例,但不能直接照抄:上海的天际线是在为城市贫困人口提供社会住房的同时实现的,但那些从零开始的新城市开发建设计划并没有考虑城市贫民窟的再开发。为了使利益相关方能够保持一种良性参与,应该建立一种更加协调的结构,用于统领保障性住房的空间分布。其中,不仅要顾及对周边社区的发展,而且要考虑到土地利用的规划。

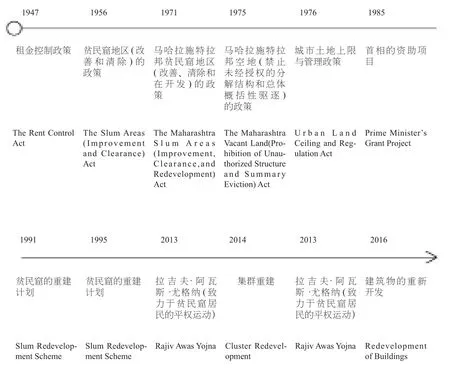

3.2 中层建筑类型解决方案:清除贫民窟

中层建筑类型解决方案提供了与高层建筑类型解决方案不同的方法来安置低收入的城市移民。在孟买,绝大部分低收入者生活在城市贫民窟。根据人口普查数据,孟买有一半以上的人口是贫民窟居民(2011年孟买城市人口普查)。为了满足日益增长的住房需求,尤其是对于城市贫民,中央和州政府制定了一系列的住房政策[5]。图5显示了从1947年到2016年,孟买的住房政策是如何实施的[5]。根据制定的方法将这些政策分为4组,即:①中央政府实施的政策;②为消除城市贫民窟而采取的政策;③促进城市贫民窟改造的政策;④最近提出的住房政策。这4个类别的政策大致上也对应于时间顺序。建筑和社区的空间布局中也有明显的趋势。它表明了一种自上而下和自下而上政策的结合。这一切归功于许多致力于为城市贫民提供住房的非营利组织的共同努力。他们不仅从以前的计划中吸取了教训,而且也积累了非常多的当地知识,用于保障性住房的空间设计。最近的政策还将原本孟买市区以外的地区纳入了孟买大城市区的整体考量。

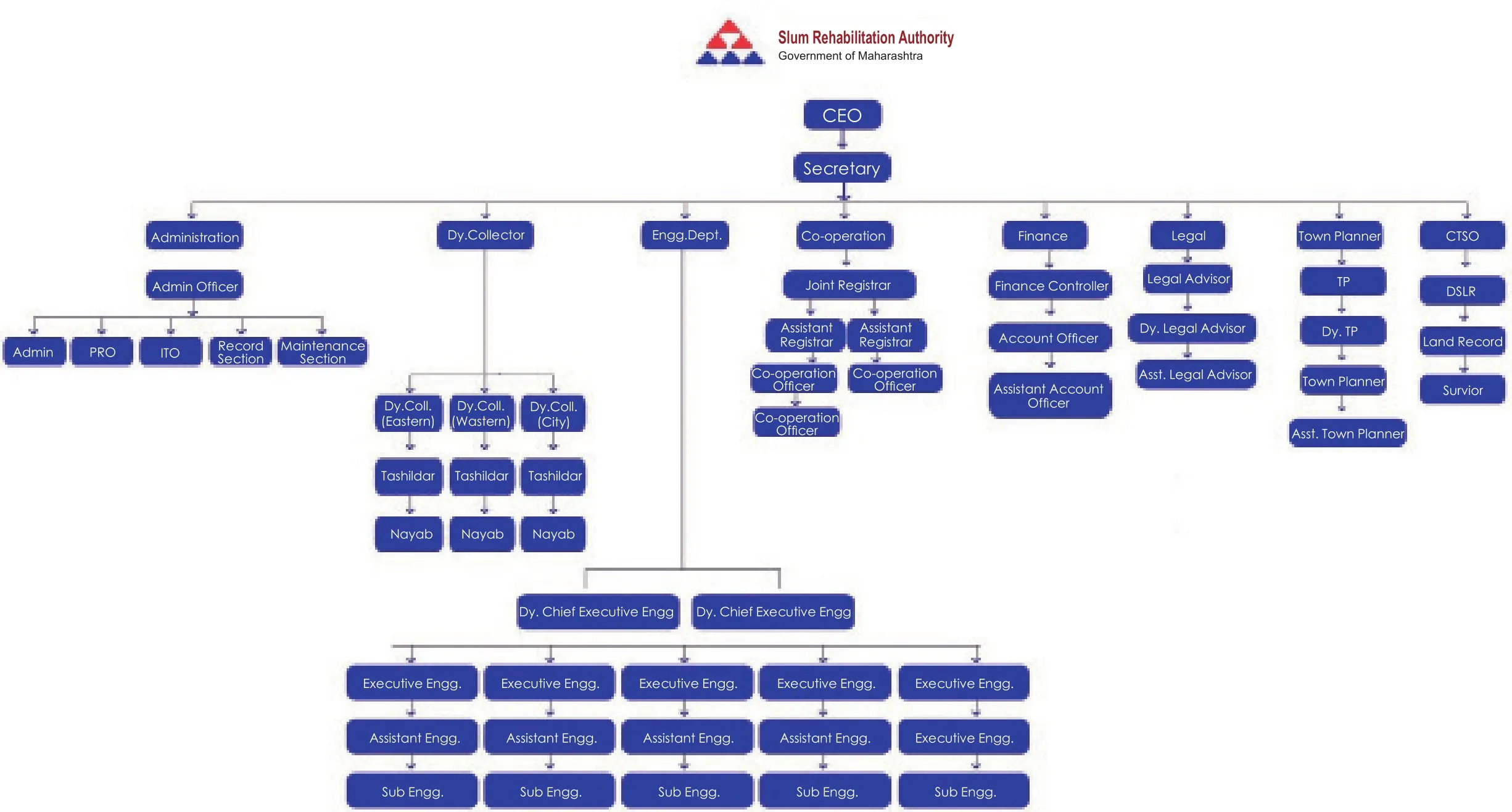

其中一个影响孟买贫民窟清理的机构是贫民窟改造局(SRA)。该组织成立于1995年,之后实施了多项贫民窟改造计划。SRA的主要职责包括:①调查和审查现有的贫民窟地区;②制订可行的计划或贫民窟改造方案;③实施

图7 / Figure 7 贫民窟改造局(SRA)的组织结构 / SRA organization structure

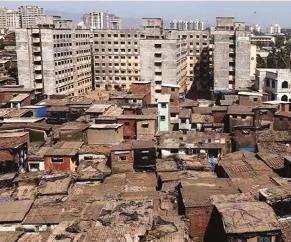

贫民窟改造计划;④实现贫民窟改造的目标。在孟买最大的贫民窟达拉维,SRA已经实施了一系列的贫民窟重建修复项目。大多数项目都采用了中层建筑类型的解决方案。图6的下图显示了达拉维当前的空间状况。中层建筑类型的房子在这个地区零星地分布着。它们中的大多数都是SRA参与的。图6中上面的图片是从贫民窟的屋顶上拍摄的,中层建筑类型的板砖房屋旨在为贫民窟居民提供正式的保障性住房。政府不仅每天提供几个小时的电力,而且所有的房屋都与城市的下水道系统和供水系统相连。那些向政府支付费用的人就可以使用这些基础设施。SRA的中层建筑类型改造计划被证明是一把双刃剑:它加速了贫民窟的清除,然而使得那些没有资格获得政府支持的贫民窟居民感到不公平。此外,更多的人会住在贫民窟里,他们希望有一天也能有资格享受国家补贴的住房。为解决这一问题,我们必须认真审视改善现有的贫民窟状况与防止更多贫民窟的形成。

中层类型学的居住解决方案避免了高层类型学建筑存在的建筑维护问题,从而使用寿命会更长。中层类型学的居住解决方案也使政府能够从当地的黑恶势力手中夺取某些贫民区的控制权。此外,它还减少了非法活动并且还试图将公共空间引入城市贫民窟内。

如果重建项目在贫民区附近,那么中层类型学的居住解决方案就能帮助贫民仍然保持社会联系。然而,那些被安置到郊区的人,确实遭受着远离经济机会的痛苦。在目前的方案下,中层类型学解决方案比高层类型学解决方案提供的居住面积更少。图7显示,在SRA的8个分支中,没有指定的部门负责贫民窟改造项目的城市设计质量。一个良好的空间设计布局实际上可以提供切实可行且具有成本效益的方法来改进中层类型学的居住解决方案。城镇规划和财政部门的协同,可以提供更加可持续的住房方案,从而可以造福更多的贫民。值得一提的是,在发展新的中层类型学的居住解决方案时,应该解决一些问题:新来者很难进入原有的体系、现有的建筑缺乏维护、儿童无法获得教育机会(尤其是英语口语的教学项目)。

总而言之,中层类型学的居住解决方案已被州政府采纳为贫民窟改造的主要策略。依赖于便利的地理位置、高可达性的轨道交通以及良好的社会资本,它有潜力为低收入者提供更多的可负担得起的住房和令人愉快的人居环境。

3.3 低层建筑类型方法:增量设计

图8 / Figure 8新孟买贝拉坡(Belapur)区的增量住房项目Incremental housing project in Belapur, New Bombay

低层类型学建筑改造方法并不等同于提供低密度的住房。相反,低层类型学改造方法可以通过渐进性递增的方式逐步改造达到高密度。这种渐进性逐步改造的方法被称为增量设计方法。这个词是由查尔斯·科里亚(Charles Correa)创造的,同时他利用这个概念改造了多个住房项目。增量式设计方法一方面是对温暖气候的一种回应,另一方面也是一种节省初始建设成本的方法,同时,整个过程与当地经济发展的前景形成良性互动。增量设计的目的是使低收入者能够在能力范围内解决居住问题。增量设计的原则包括:①提供电力使用和污水排放的基本服务;②允许业主基本采用竖向方式扩大他们的住房,以适应多年来家庭的增长;③采用一种简单的高度限制和对用地红线的尊重。除此之外,保障性住房的整个转型改造也掌握在居民自己手中。

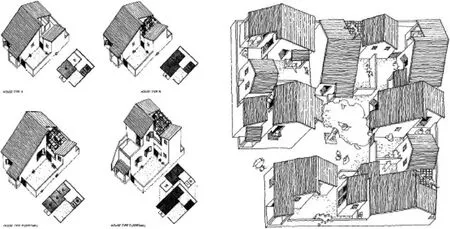

查尔斯·科里亚第一次尝试使用增量设计法可以追溯到1973年,这个项目叫作孟买的寮屋住宅。科里亚设计的寮屋住宅把开放空间安排在了中心位置,然后居住单元围绕开放空间依次展开[6]。这一设计理念随后被进一步发展为土地资源更为丰富的城市尺度的项目。在1983年,科里亚在新孟买设计了贝拉坡(Belapur)住房项目,这个项目现在被称为纳威(Navi)孟买。图8显示了从45m2到70m2的4种居住类型。它们一起形成了中间有公共开放空间的细胞结构。贝拉坡居住区继承了开放空间安排在中心的原则,然后居住单元围绕开放空间依次展开的空间特性。它也为当地居民的在经济状况的提高方面提供了多样性的机会。“贝拉坡住宅模式可以帮助90%的孟买人解决住房问题”,科里亚说,“我们试图将城市股权的模式加入到这个项目中来”。

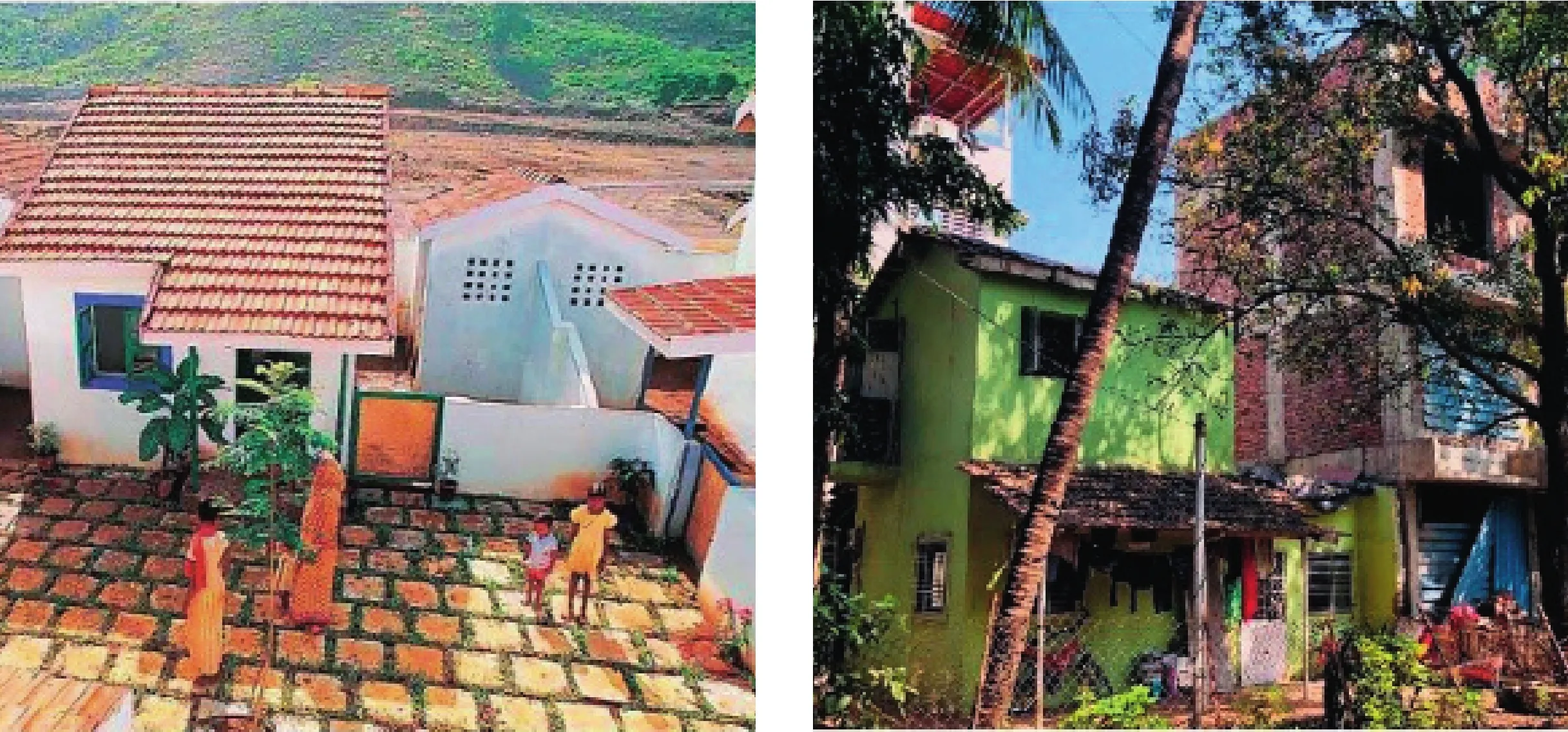

增量式住宅方案试图展示如何采用低层类型学建筑改造方法达到高密度社区的目的。此外,它还证明了可以通过空间布局的调整避免无处不在的混乱模式。增量设计不是相同单元布局的重复,而是一个个和而不同的空间单元组成的有机集群。图9中的左侧图片显示了在人工明渠或水道上的贝拉坡房屋的总体规划,这些明渠和水道有防止洪水泛滥的功能性作用。图9中右侧的图片显示了它在新孟买的战略位置以及它与孟买半岛的联系。35年后,当我们访问当地时,预期的转变(基于居民的经济状况)确实发生了。图10内的上图显示了刚完成时的住房,而图10内的下图则显示了2018年时住宅区的状况。图中间的房子被漆成绿色且保持着原有的规模和大部分的设计特色。然而,旁边的另外两幢房屋则已经在往上加建。

图9 / Figure 9查尔斯·科里亚(Charles Correa) 1983—1986年设计的纳威孟买(Navi Mumbai)的增量式住房 / Incremental housing in Navi Mumbai, designed by Charles Correa, 1983-1986

采用增量设计方法的低层类型学建筑改造方法,为城市设计如何让居者有其屋提供了一个范例。但有几个问题值得深思。首先,尽管贝拉坡住房项目与新孟买的城市中心很近,但它的建筑密度和土地稀缺程度仍然很低。应该做些什么才能使其更加适用于孟买中心区这样独特的位置?其次,庭院空间提供了一个维护公共空间来培育社会资本的机会。然而,如果在都市层面上扩大规模,如何在社区中融入更多的经济活动是非常重要的。孟买的社区不仅是消费的场所,同时也是非常重要的生产场所。最后,与20世纪80年代相比,孟买面临着截然不同的城市挑战。我们应该进一步讨论低层类型学建筑改造方法如何与例如低碳城市在内的很多环境运动保持一致。

4 属于每个人的家园

纵观这3种干预措施,高层、中层、低层类型学的建筑改造方法,在为城市贫困人口解决居住问题时各有利弊。本研究的目的不仅是将它们作为独立的方案,同时也讨论了如何将这3种改造策略的优点结合起来,为城市设计的干预创造协同策略。当孟买走向大都市的过程中,我们应该找到创新的设计策略来解决以下问题:

第一,将负担得起的住房与孟买的城市化议程结合起来。高层类型学的建筑改造方法带来了有关升级孟买基础设施的辩论。政府官员和规划者从西方(伦敦和纽约)和东方(上海和北京)的密集城市学习中意识到,地下交通可以有效地改善市中心的通勤状况。如今,在班德拉的街道上行走,随处可见“升级中的孟买”的标语。“升级中的孟买”,这已被用作宣传正在建设的第一条地铁线路的口号。然而,孟买的升级战略不应以牺牲低收入者为代价。中低层类型学建筑改造方法都提供了可以对抗城市中心的绅士化的空间干预策略。在为孟买实施中低层类型学的建筑改造时,我们应该了解背后的空间逻辑。

第二,理解空间逻辑:认识到贫民窟的形成不是随机的结果,而是对城市动态发展的合理回应。在达拉维贫民窟,正如我们前面所讨论的,我们应该把粘土社区、橡胶社区和塑料社区都有机地结合起来,以最大限度地提高它们的生活环境。我们应该首先从这些空间形态中学习,然后重新配置它们以提供更高的密度和更舒适的栖息地。我们还应该意识到,空间布局应该具有灵活性,以适应未来的变化,例如财富的积累和家庭规模的增长。

图10 / Figure 10新孟买贝拉坡(Belapur)区的增量住房项目Incremental housing project in Belapur, New Bombay

第三,未来的增量增长:渐进主义对经济状况和城市发展阶段都具有影响。城市设计干预的高、中、低类型学的解决方案可以为低收入者提供更加可持续的城市居住计划。人们来到城市是为了寻求改变的,我们将为他们从栖居地—这个神圣的空间开始,提供更多改变的可能性。

Can Urban Design Intervention Contribute to Affordable Housing in Dense Cities:Three Paradigms of Spatial Strategy in Mumbai, India

Guan ChengHe, Rahul Mehrotra

1 Introduction: Low-income Household and Urban Migrants

People from poor areas move to economically vibrant cities for employment opportunities. From the early 20th century assembly line workers of industrial cities in the United States, to the end of the century vast number of rural migrants in coastal cities of China, urban migrants were not only enticed by higher wages but also being closer to social bene fi ts they are often deprived of. However, urban migrants to high density cities often fi nd themselves in shelters of the most adverse circumstance[1]. To improve the living conditions of the urban poor, the UN Habitat proposed a variety of strategies: To provide aordable social housing(UN Habitat for Humanity), to upgrade the infrastructure by providing basic civic services (UN Urban Themes), and to intervene through channels of education and training. The challenge to implement these schemes lies in the question of how urban design can better facilitate economically viable, socially just, and environmentally sound strategies.

This paper is organized as follows: The next section provides a contextual review of Mumbai’s spatial transformation. Section 3 discusses the three urban design interventions applied in Mumbai: High-rise, mid-rise, and low-rise approaches to accommodate low-income migrants and urban poor households. Section 4 reveals the spatial logics that connects dierent types of aordable housings and proposes design strategies of a more sustainable hybrid response in dense cities.

2 Spatial Transformation of Mumbai and Urban Design Intervention

This paper focuses on Mumbai where the sheer number of slum dwellers and the tension among different social classes for land use right create challenges for new types of affordable housing strategy. In 2016, the Mumbai Metropolitan Region Development Authority (MMRDA), a body of the Government of Maharashtra responsible for the infrastructure development, proposed a 2036 regional plan for Mumbai. In this plan, new urban centers are identified, new roads are projected,and new airports are proposed. If implemented,the spatial structure of Mumbai will change from monocentricity to polycentricity. Consequently,certain land use type will be redistributed to the peripherals. During this process, affordable housing should be carefully considered and integrated to other urban functions. Who to be relocated and which social classes are entitled to remain in the already overcrowded central city?

Figure 1 shows the spatial distribution of low-income settlements in Mumbai, housing an estimated number of over 10 million. Many agencies have attempted to address informal settlement, low-income housing, and urban slums in Mumbai metropolitan region. We summarized those approaches into three paradigms of urban design interventions.

3 Three Urban Design Paradigms Providing Afordable Housing for Low-incomes

There is not a one-size- fi ts-all solution for housing the urban poor. We realized that each project has its unique aspects. We categorize them in terms of spatial formations and building typologies.

3.1 High-rise Typology Approach: Urban Upgrade

In respond to the high demand of aordable housing, one approach is to develop high-rise buildings to maximize housing capacity and achieving higher Floor Area Ratio (FAR). The concept is not so different from those famous schemes proposed by design pioneers in the 20th century: Increase the compactness while minimize the footprints of buildings. By doing so, the goal is to introduce more open space to dense cities. This approach is welcomed by those who aims to bring up Mumbai’s status to a global city. For them, what Mumbai needs is to create a more “compelling global identity”, one of the ten traits to qualify for global fl uency, as proposed by the Global Cities Initiative[2].This idea is also supported by policymakers who deem it as an opportunity to accelerate Mumbai’s urbanization. They are fascinated with the skylines of modern cities such as Shanghai or New York[3].The skyline transformation of Shanghai in the last few decades also serves well the ambition to redevelop the old industrial areas such as Parel. Figure 2 shows the spatial transformation of the mill villages, known as the Girangaon by the locals,in Parel. In 2000, the textile mills were still the dominant building typology. In 2009, demolition of the textile mills can be observed in areas west of the railway chawl and new construction has started to take o. In 2018, high-rise towers took over the mills to form the main characteristic of the area. Figure 3 depicts Parel’s skyline as a modern city with the railway chawl in the foreground.There are over one hundred high-rise buildings in Mumbai and more are under construction. It seems that the contemporary global city has taken shape.However, the supply of affordable housing stock remains insufficiency while the supply for upper middle-income group rises significantly[4]. What are the reasons behind this disparity in housing?

We need to take a closer look at a speci fi c project in Parel. The project is to redevelop urban slums in Sewri and New Policy Lines. The left image in Figure 4 shows that the existing urban texture (mainly urban slums) is replacing by highrise buildings. The government aims to move the redevelopment forward more efficiently when it entered a Public Private Partnership (P3) with the developer. The outcome of the negotiation between the government and the developer is to grant the developer the right to build luxury market price condominiums while providing aordable housing for the slum dwellers. The developer is to deliver services to maintain the aordable housing up and running for the fi rst fi ve years free of charge. The middle image in Figure 4 shows the bird’s eye view of the six aordable housing facing the fi ve even taller luxury condominiums towers. The project produced more square foot of luxury fl ats than affordable housing. Moreover, of the affordable housing constructed, many have been or will be abandoned. Why do urban poor leave affordable housings, given them almost free of charge, and where do they go?

“They simply move back to the slums”, an urbanist from the Urban Design Research Institute (UDRI),a local research institute, explained, “not because the slum is better, but the units in the high-rise building is not livable anymore”. Truly, after fi ve years (can be shorter or longer depends on the contract), the developer is no longer responsible for the maintenance of the buildings. There are many examples of elderly people stuck in the upper fl oors of high-rise buildings after the elevator shop working. No help from the government neither,they are on their own. When we visit the site, a group of youngsters playing mini cricket game in the long and dark corridor caught our eye. According to them, the elderly people depend on them to deliver bucket of water when water supply stopped.It’s hard to imagine how to survive twenty stories above ground while being cut off from basic supplied. They move out fi nally.

The high percentage of residents in the affordable high-rise towers move out after a few years are also a result of broken social networks. Urban migrants rely heavily on their connections from back home to find jobs, that is why they tend to cluster with their fellow compatriots upon arrival. But once resettled into high-rise buildings, the contacts are lost and so are their livelihoods. The current high-rise typology does not provide a sustainable solution for housing the urban poor, unless it can engage them with economic opportunities.

The high-rise typology also exacerbates traffic congestion. Zooming out to the community at large,there are multiple projects of similar scale under construction. While there is no plan to update the road system, at least in the immediate future, or to increase public transit capacity, the density has doubled. Furthermore, the newly added household are those who can afford private automobiles.It will overload the existing traffic and decrease accessibility. Finally, the spatial layout of the highrises does not provide an enjoyable inhabitable environment. In Figure 4, the left image shows the narrow space between two of the residential towers. While the campaign of “Housing for All”have launched with fi nancial strategies, the spatial design should emphasize more on public health,public safety, and the basic rights to natural light and clean water.

In sum, the high-rise typology does not provide a satisfactory nor effective housing scheme for urban poor. High-rise typology creates more traffic without sufficient infrastructure to accommodate more population who are car owners. The intention of extending the urban grid vertically is to maximize land use capacity and to upgrade Mumbai to

be a more compelling global identity. However,the implementation of the high-rise neighborhood typology is neither envisioned to accommodate urban poor in a proper way nor to support them in the long term. A series of intervention ought to be done before Mumbai allocate more of its resources,especially land, to upgrade the city skyline to meet the standard of a global city. Among them, urban design intervention can refer to experiences from precedents but not to borrow them directly: The skyline of Shanghai is achieved while social housings are provided for urban poor and those schemes proposed for building new cities from scratch are not considering redevelopment of urban slums. To align the interest of all parties involved, a more coordinated structure should be in place to overlook the spatial con fi guration of affordable housing and the integration to neighborhood development and land use planning.

3.2 Mid-rise Typology Approach: Slum Clearance

The mid-rise typology provides approach different from the high-rise typology to house the low-income urban migrants. In Mumbai, a large percentage of low-incomes are living in urban slums.According to the census data, over half of the population in Mumbai are slum dwellers (Mumbai City Population Census, 2011). Catering to the increasing housing demand, primarily urban poor,the central and state governments have produced a range of housing policies[5]. Figure 5 shows housing polices implemented in Mumbai from 1947 to 2016. Bardhan et al.[5]categorizes these policies into four groups based on the approach of formulation, they are 1) central government implemented policies; 2) polices motivated toward the removal of urban slums; 3) policies promoting the redevelopment of urban slums; and 4) recently proposed housing policies. The four categories are roughly corresponding to a chronological order. There is a clear trend toward spatial layout of buildings and neighborhoods. It indicates the incorporation of both top down and bottom up policies. This is achieved by the effort of many non-pro fi t organizations who are taking initiatives toward housing the urban poor. The lessons learnt from previous schemes also accumulated local knowledge for the spatial design of affordable housings. The more recent policies also incorporated areas beyond the Mumbai proper to the Mumbai metropolitan regions.

One of the agencies in fl uences the slum clearance in Mumbai is the Slum Rehabilitation Authority(SRA). Founded in 1995, it has carried out multiple slum rehabilitation schemes. The SRA’s main duty includes: 1) survey and review existing slum areas; 2) formulate schemes or slum rehabilitation; 3) implementation of the slum rehabilitation schemes; and 4) achieving the objective of slum rehabilitation. In Dharavi, the largest slum by resident population in Mumbai, the SRA has implemented a series of rehabilitation projects.Most of the project assumed the mid-rise typology.In Figure 6, the lower image shows the current spatial condition of Dharavi. Mid-rise housings are sporadically spreading out in the area. Most of them are products of the SRA. The upper image was taken from the rooftop of a slum house. The mid-rise slab block building is intended to provide formal housing for the slum residents. The government provides electricity for certain hours a day and all units are connected to city’s sewer system and water supplied. People who move in pay fees to the government to retain their status. SRA’s midrise scheme turns out to be a double-edged sword:It speeds up slum clearance while create inequality for those slum dwellers who are not eligible for government support. Additionally, more would come to live in slums expecting that one day they will be eligible for state subsidized housings. To deal with this issue, priorities should be set whether to improve existing slum condition or to prevent more slums from formulation.

The mid-rise typology avoided certain maintenance issues that curtailed the lifespan of high-rise typology. The mid-rise typology also enables the government to take control over certain slum area from the local ma fi a. Furthermore, it serves as a conduit to reduce illegal activities. Additionally, it attempts to introduce public space to urban slums.

If the rehabilitation projects are built in the vicinity of the slum areas, the mid-rise typology can keep the social contact in place. However, those who are relocated to the outskirts do suffer being farther away from economic opportunities. Under the current schemes, the spatial configuration of mid-rise typology provides less residential floor areas than the high-rise typology. Figure 7 shows that among the eight subdivisions of the SRA,no designated branch is responsible for the urban design quality of the slum rehabilitation projects.A well-designed spatial layout can actually provide feasible and cost-effective way to improve the midrise approach. Together with the town planning and the finance divisions, a more sustainable housing scheme, with higher density and compactness,can be delivered. Though a few issues should be addressed while developing the new mid-rise scheme: New comers are difficult to get in to the system, the existing buildings are lack of maintenance, and children have no access to educational opportunities (especially English-speaking programs).

In sum, the mid-rise typology has been adopted by the state government as the main strategy for slum redevelopment. It has potential to provide more affordable housing and enjoyable habitat for the low-incomes relying on the convenient location,high accessibility to rail transit, and well-conserved social capital.

3.3 Low-rise Typology Approach: Incremental Design

The low-rise typology is not the equivalent of providing low density housing. On the contrary, the low-rise typology can achieve high density through an incremental growth process. The approach in response to the incremental growth is called incremental design, a word coined by Charles Correa,who has realized multiple housing projects using this concept. Incremental design is a response to the warm climate, a way to save on the initial construction cost, and a process deeply rooted in economic prospects. The purpose of incremental design is to make housing affordable to the low-incomes. The principles of incremental design include: a) Provide the very basic service of electricity and sewage connection; b) Allow property owners to expand their housings, most vertically,to accommodate family growth over the years; c)Keep the very simple rules of height restriction and respect to the property line. Other than that, the transformation of the affordable housing is in the hands of its residents.

One of the first attempt to incremental housing by Charles Correa can be traced back to 1973, a project called Squatter Housing in Bombay, the current day Mumbai. The Squatter Housing has the bene fi t of open-to-sky space and centrality where the units are arranged in clusters[6]. The concept is then further developed into urban scale project where land is more abundant. In 1983, Correa designed the Belapur Housing project in New Bombay, the current day Navi Mumbai. Figure 8 shows the four types of units ranging from 45 m2to 70 m2. Together they form a cellular con fi guration with public open space in the center. The Belapur Housing inherited the spatial characteristics of open-to-sky space and centrality. It also introduced the opportunity to higher diversity, in terms of residents’ social economic status. “Belapur Housing can accommodate 90% of Bombay’s income profile,” according to Correa, “We try to add the dimension of urban equity into the project”.

The incremental housing scheme attempted to demonstrate how to design high density community using low-rise typology. Moreover, it demonstrated that the spatial layout could avoid ubiquitous patterns. Incremental design is beyond the repetition of the same unit layout but an organic cluster of similar yet distinct spatial elements. The left image in Figure 9 shows the master plan of the Belapur Housing along the manmade Nallah or watercourse to prevent fl ooding. The right image shows its strategic location in New Bombay and how it links back to the Bombay peninsula. After 35 years, when we visited the site, the expected transformation (based on residents’ economic status)did occur. Figure 10 shows the housing condition right after completion (upper) and the incremental growth in 2018 (lower). The house in the center,painted green, remains its original scale and most of the design features. The other two houses on the side, however, have been expanded vertically.

The low-rise typology using incremental design approach set an example how urban design intervention can contribute to affordable housing. There are a few questions worth contemplating. First,even though the Belapur Housing project situates in close proximity to the city center of New Bombay, it is still dealing with much lower density and land scarcity. What should be done to make it applicable in central Mumbai? Second, the courtyard space provides an opportunity to maintain communal space to cultivate social capital. However, if scaled-up at the metropolitan level, how to incorporate more economic activities in the neighborhood is of great importance. Neighborhoods in Mumbai are not only places of consumption but production. Third, comparing with the 1980s,Mumbai are all facing very diffferent urban challenges. How can low-rise typology position itself to align with environmental campaigns such as low carbon city should be further discussed.

4 Land for Everyone

The three deign interventions, high-rise, mid-rise,and low-rise typologies, all exhibit pros and cons in regard to provide adequate housing for urban poor.The intention of this research is not only present them as independent schemes but also discuss how to combine the strength of all three approaches to create synergetic tactics for urban design interventions. As Mumbai moves toward a metropolitan urban region, we should find innovative design strategies addressing the following questions:

a) Integrate affordable housing with Mumbai’s urbanization agenda: The high-rise approach brought the debate to upgrade Mumbai’s infrastructure. Learning from dense cities in the western (London and New York) as well as the east (Shanghai and Beijing), government officials and planners are aware that underground transit can be an effective way to improve inner-city commute. Today, walking on the streets of Bandra, it is hard to miss the signs saying, “Mumbai is upgrading”, which has been used as a slogan to promote the first subway line which is under construction. However, Mumbai’s upgrading should not be achieved in the expense of relocating low-incomes.Mid- and low-rise typologies both provide alternative spatial interventions which can combat gentri fi cation.To implement mid- and low-rise schemes in Mumbai,we should understand the spatial logic behind.

b) Understand the spatial logic: Recognize that the formation of slums is not a random outcome but rather a logical response to urban dynamics. In the Dharavi slum, as we discussed earlier, the clay community, the rubber community, and the plastic community are all organized in a way to maximize their productivity around their living environment.We should learn from these spatial formations and reconfigure them to provide higher density and more enjoyable habitat. We should also be aware that the spatial layout should provide the fl exibility to anticipate future changes—an incremental accumulation of wealth and growth of family.

c) Incremental growth for the future: Incrementalism has a bearing on economic status and the stage of urban development. An urban design intervention marring high-rise, mid-rise, and low-rise typologies can provide more sustainable urban housing schemes for the low-incomes. People come to cities for changes, we shall provide them with the possibility to change, starting from the very place they live—a sacred place for everyone.