Oxidative stress mitigation, kinetics of carbohydrate-enzymes inhibition and cytotoxic effects of flavonoids-rich leaf extract of Gazania krebsiana (Less.): An in vitro evaluation

Fatai Oladunni Balogun, Anofi Omotayo Tom Ashafa

Phytomedicine and Phytopharmacology Research Group, Department of Plant Sciences, University of the Free State, QwaQwa Campus, Private bag x 13, Phuthaditjhaba 9866, South Africa

1. Introduction

Flavonoids are one of the secondary metabolite of plants, which comprises more than 4 000 classes of compounds. These compounds include isoflavones, flavan-3-ol derivatives (tannins, catechins),4-oxoflavonoids (flavones and flavonols) and anthocyanins,which represent the four prominent groups[1]. Herbal preparations particularly those containing flavonoids have been used to treat many human degenerative diseases[2] such as diabetes mellitus,cancer, heart-related ailments, microbial infections,etc[1,3]. They are linked to numerous pharmacological properties such as antioxidant,antimicrobial, antiatherosclerosis, antidiabetic, anti-inflammatory,cardioprotectiveetc[1,3-5].

Gazania krebsiana(G. krebsiana) (Less.) of Asteraceae (daisy)family is indigenously referred to as terracottaGazania(Eng.),gousblom and botterblom (Afr.). The herb has been adequately described in our previous works[6,7] as an extremely flashy herb based on its warm, bright flower colour, flower size and extended flowering season. The traditional use of the plant particularly among the Basotho tribe is enormous and not limited to its usefulness in treating diabetes mellitus, cardiac-related ailments etc.Interestingly, aside the previously confirmed potentials from our research laboratory, which showed the antioxidant, antimicrobial,anthelmintic and hepatoprotective properties of the aqueous leaf extract[6,8], quantitative phytochemical determination also revealed rich amount of flavonoids from the herb[6]. Thus, investigation into the free radical scavenging, antidiabetic and cytotoxic effects of flavonoids from this plant were carried-out as to buttress the previous pharmacological study of this secondary metabolite, since no report on the flavonoid extract of the plant is found in our view in the literature.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Chemicals

Acarbose,p-nitrophenyl glucopyranoside (pNPG), porcine pancreatic alpha amylase, alpha glucosidase (Saccharomyces cerevisiae), quercetin, sucrose, maltose, butylated hydroxyl anisole(BHA), quercetin, 2,2-azinobis (3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6) sulphonic acid (ABTS), 1, 1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH), sodium nitroprusside, ferrozine,etc. were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich(South Africa). Brine shrimp eggs, other chemicals and reagents were obtained from local suppliers in pure analytical form.

2.2. Plant materials and extraction of flavonoids

The collection, identity, authentication and deposition ofG.krebsiana(BalMed/01/2015/QHB) as well as preliminary preparation of fresh leaves into powdered plant substance was according to Balogun and Ashafa[7].

Approximately 20 g each of the powdered samples was extracted by maceration with 300 mL aqueous ethanol 70% (v/v). They were filtered using Whatman No. 1 filter paper and concentrated using a rotary evaporator at 45 ℃ to obtain dry brown flavonoids extract(6.45 g translating to 32.25% yield). The extract was reconstituted in distilled water for antioxidant evaluations and in phosphate buffer(0.02 M) for antidiabetic assays. These were used to prepare a stock solution of 1 000 μg/mL from where a serial dilution were made to obtain 125, 250, 500, 750 and 1 000 μg/mL concentrations used for the assays.

2.3. In vitro free radical scavenging assays

2.3.1. DPPH radical scavenging activity

DPPH free radical activity was measured according to the method described by Bracaet al[9]. Flavonoids extract ofG. krebsiana(FEGK) (100 μL) was released to 300 μL methanolic solution(0.004%) of DPPH in a 96-well microtitre plate. After a 1 800 s incubation period in the dark, the absorbance of the mixture at 517 nm was measured and the percentage DPPH radical scavenging activity of the extract was calculated using the equation [(A0-A1)/A0]×100,where A0is the absorbance of the control, and A1is the absorbance of the extract/standard.

2.3.2. Nitric oxide scavenging activity

The nitric oxide scavenging activity of FEGK was measured according to the method of Kumaran and Karunakaran[10]. In brief, 2 mL sodium nitroprusside (10 mM), 0.5 mL phosphate buffer and 0.5 mL of varying concentrations of the extract were taken and delivered in 10 mL test tubes. Following this, the mixture was allowed to incubate at 25 ℃ for 9 000 s and 0.5 mL of 1% sulfanilamide,2% H3PO4as well as 0.1% N-(1-naphthyl) ethylenediamine dihydrochloric acid were subsequently added to end the reaction.The absorbance was measured at 546 nm on a spectrophotometer(Biochrom, England).

2.3.3. Reducing power

The method of Pulidoet al[11] was used to assess the reducing capacity of FEGK and standards. Briefly, 1.5 mL of FEGK (125-1 000 μg/mL)was diluted with 0.2 mM phosphate buffer (1 500 μL) and 1% potassium ferrocyanide (1.5 mL) in a 10 mL test tube. After the mixture was made and stood for 20 min at 50 ℃, 1 500 μL 10% trichloroacetic acid was delivered into the tube and the whole mixture was centrifuged at 650×gfor 10 min. Approximately 1 250 μL from the supernatant was pipetted and mixed with distilled water in the same ratio with the addition of FeCl3(0.25 mL, 0.1%). The absorbance of the mixture was determined at 700 nm on a spectrophotometer.Increased absorbance values indicated higher reducing capacity.

2.3.4. Metal chelating activity

The chelating activity of FEGK was measured using the method of Diniset al[12]. Summarily, the extract (0.05 mL) was diluted with 0.25 mL (2 mM) FeCl2solution. Then 100 μL of 5 mM ferrozine was subsequently added to initiate the reaction, agitated and afterwards allowed to stand for 600 s at 25 ℃. Spectrophotometric determination at 562 nm was carried on the mixture. The percentage inhibition of ferrozine-Fe2+complex formation was determined using the expression above.

2.3.5. ABTS radical determination

The method of Reet al[13] was used to determine the ABTS+scavenging ability of FEGK. In summary, 20 mL of 7 mM aq. ABTS and 2.45 mM K2S2O7were separately prepared, and were mixed together after being kept in the dark for 16 h. A total volume of 20 μL aliquot was added to 200 μL ABTS solution and absorbance reading was measured at 734 nm using a microplate reader (BIO RAD, Japan) after incubation for 15 min.

2.3.6. Hydroxyl radical evaluation

Hydroxyl radical scavenging activity was measured according to the procedure of Sindhu and Abraham[14]. In brief, 50 μL aliquot, 20 μL 500 μM FeSO4, 60 μL 20 mM deoxyribose, 20 μL 20 mM H2O2,200 μL 0.1 M phosphate buffer were added into a 1 mL Eppendorf tube. The mixture was made to 400 μL with distilled water and afterwards incubated for 1 800 s at 25 ℃. The reaction was brought to an end by mixing 0.25 mL and 0.2 mL of trichloroacetic acid(2.8%) and TBA (0.6%) solutions respectively. Then 250 μL was transferred into 96-well plate to determine the absorption of the mixture at 532 nm following the incubation for 1 200 s at 100 ℃.

2.4. In vitro antidiabetic potentials

The in vitro antidiabetic effect of FEGK was evaluated by determining inhibition of α-amylase, α-glucosidase, sucrase and maltase activities.

2.4.1.α-amylase inhibitory assay

The modified protocol described by Balogun and Ashafa[15] was used for this assay. A total of 50 μL of the extract/acarbose (125-1 000 μg/mL) was mixed with 50 μL α-amylase (0.5 mg/mL) in 0.02 M phosphate buffer (PB; pH 6.9) and pre-incubated at 25 ℃ for 600 s. A total volume of 50 μL (1%) starch solution (prepared in PB) was added and incubated at 25 ℃ for 600 s. The reaction mixture was stopped by introducing 100 μL of dinitro salicylic acid reagent. The final incubation of the mixture in 100 ℃ hot water for 300 s was carried out. The mixture was cooled and diluted with 1 mL distilled water for absorbance at 540 nm. The whole step was repeated for the control except that the aliquot was replaced with distilled water. The α-amylase inhibitory activity was calculated as percentage inhibition following the above expression and the half maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) was determined graphically.

2.4.2. Mode ofα-amylase inhibition

The mode of inhibition of the enzyme by FEGK was similarly according to method of Balogun and Ashafa[15]. Briefly, 0.25 mL of the extract (5 mg/mL) was pre-incubated with 0.25 mL α-amylase solution in PB for 600 s at 25 ℃ in one set of 5 test tubes, while concurrent pre-incubation of 0.25 mL of PB with 250 μL of α-amylase was performed in another set of test tube. A 0.25 mL starch solution in increasing concentrations (0.30-5.00 mg/mL)was added to all test tubes, and dinitro salicylic acid was added to stop the procedure. A maltose standard curve was used to determine the amount of reducing sugars released and converted to reaction velocities. The mode of inhibition of FEGK against α-amylase activity was determined using Lineweaver and Burk[16] plot.

2.4.3.α-glucosidase inhibitory assay

The effect of the FEGK on α-glucosidase activity was measured according to the method by Kimet al[17] using α-glucosidase fromSaccharomyces cerevisiae.pNPG (5 mM) was added in 0.02 M phosphate buffer (pH 6.9) for the preparation of the substrate solution. Summarily, 50 μL of varying concentrations of FEGK(125-1 000 μg/mL) was pre-incubated with 0.1 mL of α-glucosidase(0.5 mg/mL) in a test tube and 50 μL ofpNPG was added to trigger the reaction. They were incubated at 37 ℃ for 1 800 s, and 2 mL of 0.1 M Na2CO3was added to terminate the process. The α-glucosidase activity was evaluated by measuring the development of yellow coloured para-nitrophenol (pNP) released frompNPG at 405 nm. Percentage inhibition was determined in line with the expression in 2.3.1 and the IC50was determined as above.

2.4.4. Mode ofα-glucosidase inhibition

The method expressed by Balogun and Ashafa[15] was adopted to assess the kinetics of inhibition of alpha glucosidase by FEGK. In brief, 50 μL of the (5 mg/mL) aliquot was reacted with 0.1 mL of α-glucosidase solution for 600 s at 25 ℃ in a set of 5 test tubes while the same volume of α-glucosidase was reacted with 50 μL of PB (pH 6.9) concurrently in another set of 5 tubes. A total of 50 μLpNPG at increasing concentrations (0.125-2.000 mg/mL) was immediately added to the two sets of test tubes to activate the reaction. The two mixtures were incubated at 25 ℃, and 500 μL of Na2CO3was added to end the whole process. A p-NP standard was used to determine spectrophotometrically the amount of reducing sugars released, and kinetics of FEGK on α-glucosidase activity was determined using Michaelis-Menten kinetics.

2.4.5. Sucrase and maltase inhibition assays

The FEGK effect on the activities of sucrase and maltase were determined according to the methods of Kimet al[17] using α-glucosidase fromSaccharomyces cerevisiae. Sucrose (50 mM) and maltose (25 mM) which were the substrate solutions were prepared in 0.02 M PB (pH 6.9). The entire steps were repeated according to the earlier described method for alpha glucosidase. The substrate(pNPG) was replaced with sucrose and maltose and the absorbance was measured at 540 nm instead of 405 nm. The sucrase and maltase activities were determined as percentage inhibition and IC50as above.

2.4.6. Kinetics of sucrase and maltase inhibition

The modified method of Balogun and Ashafa[15] was used to determine the kinetics of inhibition of sucrase and maltase by flavonoids extract ofG. krebsianaleaf. The mode of inhibition of the two enzymes was evaluated by replacingpNPG with sucrose and maltose.

2.5. Brine shrimp lethality assay (BSLA)

The collection of the larvae from the brine shrimp eggs was according to method by Meyeret al[18]. Approximately 17 g brine shrimp eggs was weighed and emptied into a 1 000 mL plastic beaker (hatching chamber) with a partition for dark (covered) and light areas while 500 mL of filtered, artificial seawater was then introduced. Introduction of the eggs was towards the dark side of the chamber and the lamp maintained above to cover the other side(light) so as to attract the hatched shrimps with further development into mature nauplii (larva) using 2 880 min process time. The method of Olajuyigbe and Afolayan[19] was adopted to carry out the BSLA after 48 h of harvesting the matured shrimp larvae. In brief,FEGK was prepared in five concentrations (125, 250, 500, 1 000,2 000 μg/mL) with filtered seawater for the assay. Five mL of each concentration of FEGK as well as 10 shrimps were emptied into the 10 mL vial and tested in triplicates. For the control, three vials containing 5 mL fresh seawater and with 10 shrimps were set aside and all the test tubes were left uncovered under the lamp. To ensure that the mortality was not characterized by starvation but due to the bioactive compounds in FEGK, the total number of deaths between the treatments and control was compared, while the numbers of the shrimps alive in all the vials were also taking into consideration and were recorded after 24 h. Using probit analysis, lethality concentration resulting in 50% mortality of the larvae (LC50) was assessed at 95% confidence intervals. The percentage mortality (%M) was also calculated using the expression below:

% Mortality=Number of dead nauplii/Total of nauplii×100

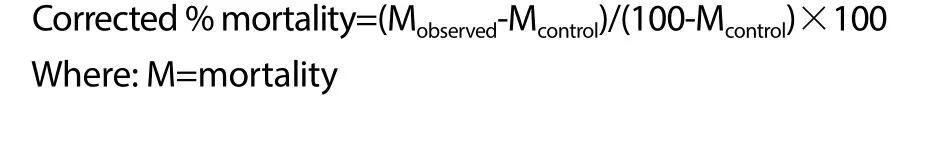

It is important to note that there is a need to adjust the observed deaths in the treatment groups to the control in situations where few treatments are tested and such correction is traditionally calculated using mathematical expression developed by Abbot[20]. Similarly,it must be aware that the adjusted value should not be greater than 20%. Thus, the corrected mortality in this experiment is acquired following the expression below:

2.6. Statistical analysis

Data analysis were done by one-way analysis of variance, followed by Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test and results were expressed as mean±SEM using Graph Pad Prism version 3.0 for windows,Graph Pad software, San Diego, California, USA.

3. Results

3.1. Antioxidant assays

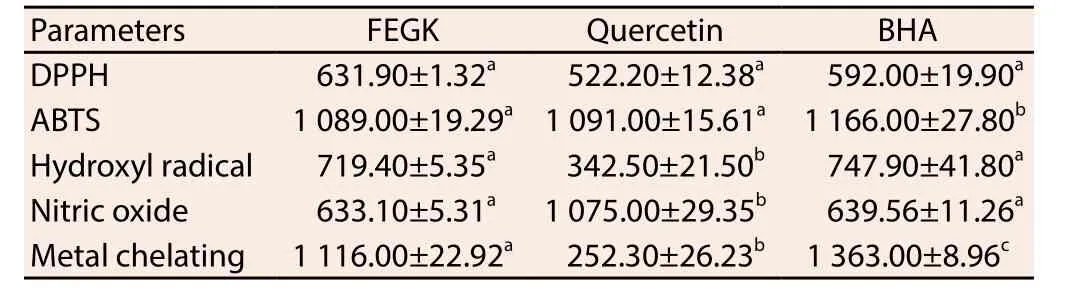

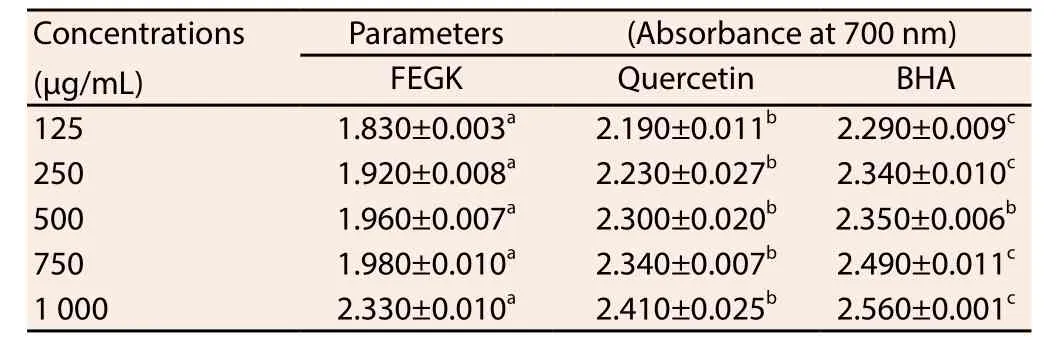

The result from the free radical scavenging activities of the extract is shown in Table 1 and the inhibitions of the extracts and standards were dose-dependent. Based on IC50values obtained, it was observed that FEGK revealed the best activity in ABTS and nitric oxide radical scavenging activities, with an IC50values of 1 089 and 633 μg/mL when compared with quercetin 1 091 μg/mL (P>0.05)and 1 075 (P<0.05) μg/mL, as well as BHA 1 166 μg/mL (P<0.05)and 639 (P>0.05) μg/mL, respectively. Similarly, it showed better insignificant (P>0.05) activity against hydroxyl radical (719.90 μg/mL) and significant (P<0.05) metal chelating (1 116 μg/mL) when compared with BHA (747.90 and 1 363 μg/mL respectively) though quercetin activity (342.50 and 252.30 μg/mL) was significantly(P<0.05) better for both assays. Quercetin with IC50value of 522.20 μg/mL as well as BHA (592 μg/mL) exhibited insignificant better activity against DPPH as compared to the extract while the extract and the standards showed significant (P<0.05) higher absorbance difference from each other in most of the concentrations for reducing capacity (Table 2).

Table 1 IC50 of flavonoid-rich leaf extract from G. krebsiana (μg/mL).

Table 2 Reducing capabilities of FEGK and standards.

3.2. Antidiabetic inhibitory assays and kinetics of inhibition

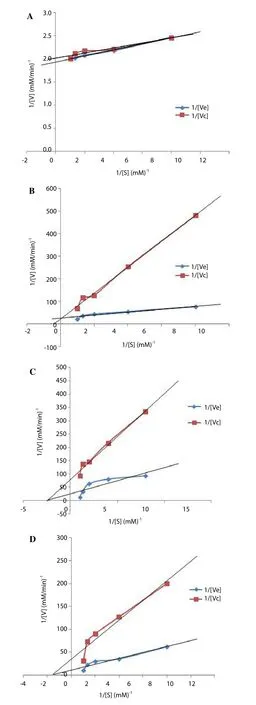

FEGK revealed significant (P<0.05) better activity against alpha glucosidase when compared with acarbose, although acarbose showed statistically better activity than FEGK against alpha amylase.It was also observed that FEGK inhibited alpha amylase mildly as compared to alpha glucosidase, which indicated a strong inhibition.The Lineweaver Burk plot revealed an uncompetitive inhibition of alpha amylase by FEGK (Figure 1A) with a decline in theVmaxandKmvalues from 0.52 to 0.49 mM/min as well as from 0.03 to 0.02 mM-1respectively. There was a constantVmaxvalue (0.04 mM/min)for both the FEGK and the control with an increase inKmvalues from 0.26 to 2.75 mM-1for alpha glucosidase, which indicated a competitive inhibition (Figure 1B). Moreover, a non-competitive inhibition occurred for sucrase (Figure 1C) and maltase (Figure 1D) as both enzymes revealed a constantKmvalues of 0.60 and 0.41 mM-1respectively with varying reduction inVmaxvalues from 0.09(FEGK) to 0.03 (control), and from 0.04 (FEGK) to 0.01 (control)mM/min, respectively.

Figure 1. Kinetics of alpha amylase (A) alpha glucosidase (B), sucrase (C)and maltase (D) by flavonoid-rich leaf extract of G. krebsiana (Less.) showing an uncompetitive, competitive, non-competitive and non-competitive inhibitions respectively.

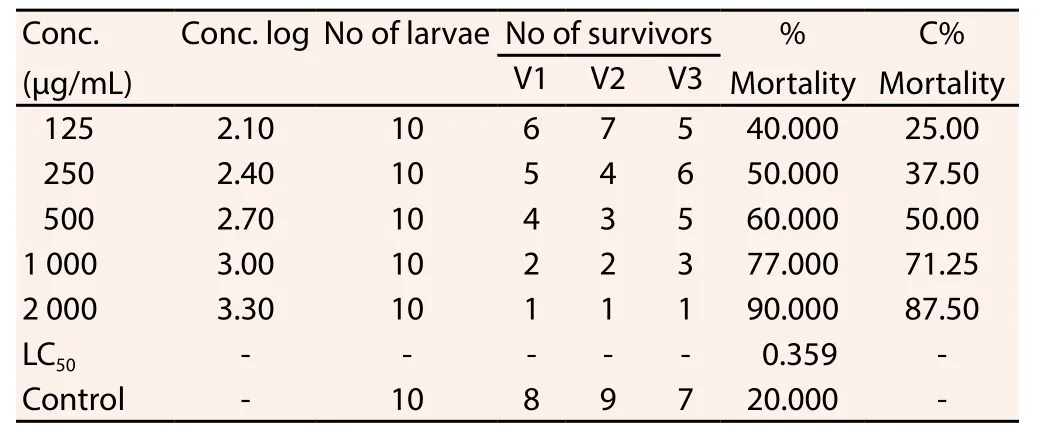

3.3. BSLA result

The BSLA result was shown in Table 3. It was observed that the concentration of the extract (FEGK) was directly proportional to the extent of lethality at 359 μg/mL (R2=0.833) and the highest mortality was observed at 90% for this investigation.

Table 3 Effect of FEGK on brine shrimp lethality.

4. Discussion

The most essential secondary metabolites from plants are flavonoids and phenolic acids, which have excellent bioactive compounds[21] effective against many ailments. Flavonoids are natural antioxidants, and have great potential against oxidative stress resulting from excessive free radicals production[22] linked to the etiopathology of many diseases. They have the inherent properties to mitigate against these radicals via metal (e.g. Fe, Cu2+) chelating effect by the removal of the causal factor that enhance the production of free radicals, triggering the interaction with antioxidant enzymes,scavenging reactive oxygen species by hydrogen atom donationetc[23] mechanisms. From the present investigation, the ability of FEGK to inhibit the activities of these free radicals particularly ABTS, nitric oxide and DPPH either at par or better than standards is in fact sin qua non to its antioxidant effect[5]. This report corroborates with study from Prior and Cao[24] as well as Dai and Mumper[25] that established the effectiveness of flavonoids than synthetically-made antioxidants such as vitamins A and C.

The non-insulin dependent diabetes mellitus (DM), or type 2 DM,is epitomized by derangement in the metabolism of carbohydrates,protein and lipid metabolisms arising from abnormalities in insulin secretion, insulin inaction or both. The management or prevention of DM by the use of oral hypoglycaemic agents such as insulin, acarbose etc. comes with side effects, thus natural occurring flavonoids would be proposed as the alternative therapy for DM management[5]. Moreover, in postprandial hyperglycaemia,prominent carbohydrate-hydrolyzing enzymes such as alpha amylase, alpha glucosidase are responsible for constant breakdown of complex carbohydrate to glucose, thus aggravating blood glucose level. Hence, acarbose, miglitoletc. which are inhibitors of these enzymes serve as suitable antidote for regulating hyperglycaemia and act by slowing down the digestion of complex carbohydrates to glucose for onward utilization into body tissues.

In this study, the impact of FEGK on these enzymes including sucrase and maltase (classes of alpha glucosidase) as well as their activities were evaluated. The mild inhibition of alpha amylase (1 661 μg/mL) and strong inhibition of alpha glucosidase (487.80 μg/mL),sucrase (547.80 μg/mL) and maltase (607.10 μg/mL) by FEGK with higher IC50value of alpha amylase is suggestive of potent amylase inhibition[26-28], since inhibition of alpha amylase could bring about fermentation of carbohydrates yet to be digested by bacterial present in the colon[29]. It has been reported that for any hypoglycaemic agent to exhibit their antihyperglycaemic effect devoid of side effects (flatulence, diarrhoea) as observed with synthetic inhibitors(acarbose), it must be able to inhibit alpha amylase mildly and as well inhibit alpha glucosidase strongly[15]. The double reciprocal curve revealed the kinetics of inhibition of the enzymes, expressed the uncompetitive inhibition of alpha amylase which is evident from the reduction inVmaxandKmvalues. This is an implication of the binding of FEGK at other sites on the enzyme substrate complex,thereby diminishing the substrate binding to the enzyme which ultimately delays starch disintegration to smaller sugars[30]. On the other-hand, the Line Weaver Burk plot established the ability of FEGK at competitively inhibiting alpha glucosidase activity, which indicated that FEGK contested with the substrate at the active site of the enzyme, thus elongating the carbohydrate digestion time to glucose. The double reciprocal plot of reaction velocity, 1/[V]against substrate concentration, 1/[S] showed a constantKmand a decrease inVmaxvalues, which revealed that sucrase and maltase were non-competitively inhibited by FEGK. This demonstrated that FEGK bonded at other sites aside the active site of the enzyme with the likelihood of adhering to either the free enzyme or the enzymesubstrate complex, thus modifying the activity of the substrate or the enzyme or both[31]. Above all, the antihyperglycaemic effect of FEGK as examined in this study strengthened the work of Weisset al[32] on the antidiabetic activity of flavonoids.

Brine shrimp lethality assay is an important procedure for basic evaluation of toxicity emanating from medicinal plants extract.Aside from this, other applications of this protocol are not limited to the detection of toxins from fungi, cyanobacteria, pesticides and heavy metals[33]etc. The assay is designed to assess the ability of the sample to eliminate or destroy brine shrimp organism[34]. FEGK at the highest concentration achieved 90% mortality ofArtemia(salina) nauplii brine shrimp with median lethal concentration (LC50)value of 359 μg/mL, which suggested the potent (active) effect of the extract[18]. The result is consistent with studies from Murakamiet al[35] and Trifunschi and Ardelean[36] forFicus caricaon the anticancer activity of flavonoids.

In summary, the study confirmed the cytotoxic, antioxidant and antidiabetic potentials of flavonoids and laid credence to the potential use of flavonoids-rich leaf extract ofG. krebsianaas nutraceuticals or phytonutrients against free radicals, diabetes and cancer.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors had no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the support from Directorate Research and Development, University of Free State, South Africa for the Postdoctoral Research Fellowship granted Dr. FO Balogun (No.2-459-B3425) tenable at the Phytomedicine and Phytopharmacology Research Group, UFS, QwaQwa Campus, South Africa.

[1] Salvamani S, Gunasekaran B, Shaharuddin NA, Ahmad SA, Shukor Y.Antiartherosclerotic effects of plant flavonoids.Biomed Res Int2014; Doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2014/480258.

[2] Havsteen B. Flavonoids, a class of natural products of high pharmacological potency.Biochem Pharmacol1983; 32(7): 1141-1148.

[3] Kumar S, Gupta A, and Pandey AK. Calotropis procera root extract has capability to combat free radical mediated damage.ISRN Pharmacol2013; 2013: 691372. Doi: 10.1155/2013/691372.

[4] Kumar S, Pandey AK. Phenolic content, reducing power and membrane protective activities ofSolanum xanthocarpumroot extracts.Vegetos2013;26(1): 301-307.

[5] Vinayagam R, Xu B. Antidiabetic properties of dietary flavonoids: a cellular mechanism review.Nutr Metab2015; 12: 60. Doi: 10.1186/s12986-015-0057-7.

[6] Balogun FO, Ashafa AOT. Antioxidant, hepatoprotective and ameliorative potentials of aqueous leaf extract ofGazania krebsiana(Less.) against carbon tetrachloride (CCl4)-induced liver injury in Wistar rats.Transac Royal Soc S Afr2016; 71(2): 145-156.

[7] Balogun FO, Tshabalala NT, Ashafa AOT. Antidiabetic medicinal plants used by the Basotho tribe of Eastern Free State: a review.J Diabetes Res2016; Doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2016/4602820.

[8] Tshabalala BD, Alayande KA, Sabiu S, Ashafa AOT. Antimicrobial and anthelmintic potential of root and leaf extracts ofGazania krebsianaLess.subsp. serrulata (DC.) Roessler: Anin vitroassessment.Eur J Integr Med2016; 8(4): 533-539.

[9] Braca A, Tommasi ND, Bari LD, Pizza C, Politi M, Morelli I. Antioxidant principles fromBauhinia terapotensi.J Nat Prod2001; 64(7): 892-895.

[10] Kumaran A, Karunakaran RJ.In vitroantioxidant activities of methanol extracts of fivePhyllanthusspecies from India.LWT2007; 40(2): 344-352.

[11] Pulido R, Bravo L, Saura-Calixto F. Antioxidant activity of dietary polyphenols as determined by a modified ferric reducing/antioxidant power assay.J Agric Food Chem2001; 48(8): 3396-3402.

[12] Dinis TCP, Madeira VMC, Almeida LM. Action of phenolic derivatives(acetoaminophen, salycilate and 5-aminosalycilate) as inhibitors of membrane lipid peroxidation and as peroxyl radical scavengers.Arch Biochem Biophys1994; 315(1): 161-169.

[13] Re R, Pellegrini N, Proteggente A. Antioxidant activity applying an improved ABTS radical cation decolorisation assay.Free Rad Bio Med1999; 26(9-10): 1231-1237.

[14] Sindhu M, Emilia Abraham T.In vitroantioxidant activity and scavenging effects of Cinnamonium verum leaf extract assayed by different methodologies.J Food Chem Toxicol2005; 44(2): 198-206.

[15] Balogun FO, Ashafa AOT. Aqueous roots extract ofDicoma anomala(Sond.) extenuates postprandial hyperglycaemiain vitroand its modulation against on the activities of carbohydrate-metabolizing enzymes in streptozotocin-induced diabetic wistar rats.S Afr J Bot2017;112: 102-111.

[16] Lineweaver H, Burk D. The determination of enzyme dissociation constants.J Am Chem Soc1934; 56(3): 658-666.

[17] Kim YM, Jeong YK, Wang MH, Lee WY, Rhee HI. Inhibitory effects of pine bark extract on alpha-glucosidase activity and postprandial hyperglycemia.Nutrition2005; 21(6): 756-761.

[18] Meyer BN, Ferrigni NR, Putnam JE, Jacobsen LB, Nichols DE,McLaughlin JL. Brine shrimp: a convenient general bioassay for active plant constituents.Plant Med1982; 45(5): 31-34.

[19] Olajuyigbe OO, Afolayan AJ. Pharmacological assessment of the medicinal potential ofAcacia mearnsiide wild: antimicrobial and toxicity activities.Int J Mol Sci2012; 13(4): 4255-4267.

[20] Abbot WS. A method of computing the effectiveness of an insecticide.J Econ Entomol1925; 18(2): 265-267.

[21] Kim D, Jeond S, Lee C. Antioxidant capacity of phenolic phytochemicals from various cultivars of plums.Food Chem2003; 81: 321-326.

[22] Ghasemzadeh A, Ghasemzadeh N. Flavonoids and phenolic acids: role and biochemical activity in plants and human.J Med Plants Res2011;5(31): 6697-6703.

[23] Kumar S, Pandey AK. Chemistry and biological activities of flavonoids: an overview.Sci World J2013; Doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2013/162750.

[24] Prior RL, Cao G. Antioxidant phytochemicals in fruits and vegetables:diet and health implications.Hortic Sci2000; 35(4): 588-592.

[25] Dai J, Mumper R. Plant phenolics: extraction, analysis and their antioxidant and anticancer properties.Molecules2010; 15(10): 7313-7352.

[26] Kazeem MI, Ashafa AOT.In-vitroantioxidant and antidiabetic potentials ofDianthus basuticusBurtt Davy whole plant extracts.J Herbal Med2015; 5: 158-164.

[27] Mbhele N, Balogun FO, Kazeem MI, Ashafa T.In vitrostudies on the antimicrobial, antioxidant and antidiabetic potentials ofCephalaria gigantea.Bangladesh J Pharmacol2015; 10: 214-221.

[28] Kazeem MI, Ashafa AOT. Kinetics of inhibition of carbohydratemetabolizing enzymes and mitigation of oxidative stress byEucomis humilisBaker bulb.Beni-Suef Uni J Basic Applied Sci2017; 6: 57-63.

[29] Sabiu S, Ashafa AOT. Membrane stabilization and kinetics of carbohydrate metabolizing enzymes (α-amylase and α-glucosidase)inhibitory potentials of Eucalyptus obliqua L.Her. (Myrtaceae) blakely ethanolic leaf extract: anin vitroassessment.S Afr J Bot2016; 105: 264-269.

[30] Shai LJ, Masoko P, Mokgptho MP, Magano SR, Mogale AM, Boaduo N,et al. Yeast alpha-glucosidase inhibitory and antioxidant activities of six medicinal plants collected in Phalaborwa, South Africa.S Afr J Bot2010;76: 465-470.

[31] Mayur B, Sandesh S, Shruti S, Sung-Yum S. Antioxidant and α-glucosidase inhibitory properties ofCarpesium abrotanoidesL.J Med Plant Res2010; 4(15): 1547-1553.

[32] Weiss L, Barak V, Raz I, Or R, Slavin R, Ginsburg. Herbal flavonoids inhibit the development of autoimmune diabetes in NOD mice: proposed mechanisms of action in the example of PADMA 28.Altern Med Stud2011; 1(1). Doi: 10.4081/ams.2011.e1.

[33] Vajha M, Krishna CSR. Evaluation of cytotoxicity in selected species ofCarallumaandBoucerosia.Asian J Plant Sci Res2014; 4(4): 44-47.

[34] Wu C. An important player in brine shrimp lethality bioassay: the solvent.J Adv Pharm Technol Res2014; 5(1): 57-58.

[35] Murakami A, Tanaka T, Lee JY, Surh YJ, Kim HW, Kawabata K, et al.Zerumbone, a sesquiterpenes in subtropical ginger, suppresses skin tumor initiation and promotion stages in ICR mice.Int J Can2004; 110(4):481-490.

[36] Trifunsch IT, Ardelean DG. Flavonoid extraction fromFicus caricaleaves using different techniques and solvents.J Nat Sci2013; 125: 79-84.

Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Biomedicine2018年1期

Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Biomedicine2018年1期

- Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Biomedicine的其它文章

- Prevalence of coronavirus from diarrheic calves in the Republic of Korea

- Effective Aeromonas specific monoclonal antibody for immunodiagnosis

- Pharmacodynamic profiling of optimal sulbactam regimens against carbapenemresistant Acinetobacter baumannii for critically ill patients

- Efficiency of combining pomegranate juice with low-doses of cisplatin and taxotere on A549 human lung adenocarcinoma cells

- Correlation of phytochemical content with antioxidant potential of various sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas) in West Java, Indonesia

- Larvicidal activity of Xenorhabdus and Photorhabdus bacteria against Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus