生态设计不仅仅是顺应自然—美国风景园林师乔治·哈格里夫斯专访

采访/整理:张博雅

访谈人物:

(美)乔治·哈格里夫斯/哈格里夫斯事务所创始人/美国风景园林师协会会员/曾任教于美国哈佛大学设计研究生院,并任风景园林系主任(1996—2003)

Profile:

(USA) George Hargreaves, is the founder and Design Director of Hargreaves Associates. He is a fellow of the American Society of Landscape Architects. He taught at the Graduate School of Design, Harvard University for 20 years, was tenured there for 12 years, and served as the chairman of the Department of Landscape Architecture from 1996 to 2003.

什么样的设计才是“生态”的?在“生态修复”已经上升为国家政策的今天,这是风景园林师必须回答的问题。在中国,生态设计常常让人联想到未经修剪的植被,为动物栖息地创造生境等。不过,把项目做得“自然”就等同于“生态”吗?在真实的项目实践中,设计师所掌握的设计语汇仍然十分有限。在生态设计领域,我们的欧美同行比我们更早开始探索。了解其他国家和地区的先进经验,对中国设计师大有裨益。

本刊记者邀请到美国著名风景园林师—乔治·哈格里夫斯,详细探讨了他的设计哲学和生态设计思想。他所成长的20世纪60年代,是美国生态主义思想兴起和发展的年代。他自80年代从业以来即接触棕地更新类项目,并从当时的新潮大地艺术中汲取灵感,创造性地应用于景观设计项目中。他曾参与设计了包括伦敦的伊丽莎白女王奥林匹克公园在内的多个重要项目,在大型公园以及棕地更新的理论与实践中均有突出贡献。2016年,哈格里夫斯事务所同时获得库伯·休伊特国家设计奖和罗莎·芭芭拉国际景观奖2项殊荣。

LA:《风景园林》

George:乔治·哈格里夫斯

LA:让我们从您职业生涯的开始聊起吧。据记载,您对于风景园林最初的兴趣来源于一次落基山之旅。在那次旅行中,是什么打动了您呢?旅行结束后,又是什么让您坚定地走上了风景园林之路呢?

George:探索大地景观是很吸引人的。当我在徒步的时候,我注意到植被随着海拔的变化而变化。山顶的植物和山脚下是完全不同的。这对于当时的我来说非常新奇。我对于大地景观本身和景观所蕴含的空间很着迷。起初,我想或许我可以学习林业。不过,我叔叔那时候在佐治亚大学工作,他建议我考虑一下风景园林。我去参观了学院,那里的人在做公园之类的东西。于是我想:对,这就是我想做的。

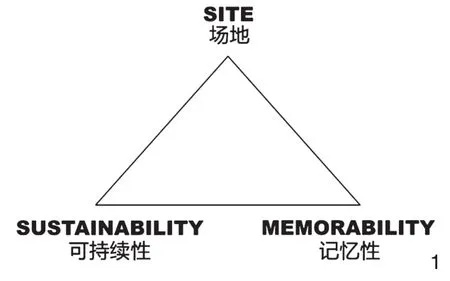

1 三角形理论Triangle theory

LA:对于设计,您有一个“三角形理论”—设计的3个关键因素是在场地、可持续性和记忆性(图1)。这似乎是您所有项目的概念基础。这个“三角形”对您来说意味着什么?为什么记忆性如此重要呢?

George:我总是对场地很感兴趣,我认为设计应该因地制宜。至于可持续性,很多人是从生态学的角度去思考的,但是我是从经济的角度出发的。我对很多古老的公园和花园印象深刻,特别是伦敦的海德公园和圣·詹姆斯公园。几百年来,人们持续地投入大量财富去维护这些公园。在这里可持续性意味着需要有人持续付出人力物力。说到这儿就不得不提记忆性。当一个公园被铭记、被喜爱的时候,它将与人们产生关联,使用者可以从公园中获益。如果你的项目只是在生态上可持续,但并不能让人们产生情感共鸣,那么人们除了“可持续性”这个概念本身就再也记不住别的了。那样的话你就失败了。通过把场地变得容易被惦记、被喜爱,人们会自发地去投入、去维护你的项目。

LA:的确如此。您的作品的识别性都很强,人们很容易通过雕塑般的地形辨认它们。这些地形的灵感来源于哪里呢?

George:我是从读研究生的时候开始用地形做设计的。那时的设计师常常通过平面上的几何秩序做设计,我则极力去寻找一种新的表达方式。在一些历史景观的启发下,我开始尝试做脱离平面的设计。地形就是我设计的全部。我在研究生毕业后做的最早的项目之一是一处25hm2的垃圾填埋场,而且业主只有50万美元的预算。那意味着我们只能在场地上做一件事,比如全部种满树,或是种满草之类的。最后,对于预算有限的大尺度项目,地形成为(我们的)设计语言。

LA:这样说来,通过地形做设计在20世纪80年代是独树一帜的。您也是在那时开始介入棕地项目的吗?

George:我是第一批把地形当作首要设计手段的设计师之一。罗伯特·史密森等艺术家给了我灵感。我的项目和艺术作品的区别是,我的项目都是公共空间,而大部分当代大地艺术作品都在人迹罕至之处,且只能在外部远观。

从某种意义上说,在那个时候,是棕地选择了我。最开始,我的公司规模很小。当大公司在为地产商设计花园时,我有着完全不同的客户。来找我们的人通常没什么钱,而且他们有棘手的问题要处理。他们觉得我们的策略(地形设计)很有创意,也不用花太多钱。不言而喻,这是我们的机会,我们只能全力以赴,对吧?

当然了,我的方法也是在不断更新的。几年以后,我意识到并不是每个项目都适合做地形。我开始更多地考虑植物等其他因素。如今,我们有一套完整的设计手段和设计元素,地形和其他要素是平等的关系。

LA:您曾经提到过,地形是和自然过程相关联的。这在您的项目中是如何体现的呢?

George:你知道,我不是艺术家。我认为仅有地形是不能构成一个项目的。我试着让地形和自然过程产生关联,让地形去强调本就存在的自然过程。在烛台角文化公园中,我们试着把旧金山湾区强烈的风和海浪纳入设计。我们让地形和自然的风向互动。当你穿过起伏的地形时,你能感受到不同的风,有时你完全暴露在风里,有时你又被地形庇护。我们还设计了可以让潮汐进出的水湾,让原本只是垂直变化的海浪产生了水平方向的变化。虽然海浪一直在那里,但这个水湾让人们看到了以前不曾看到的自然变化①(图2~4)。

LA:说到生态设计,我们不得不提伊恩·麦克哈格的《设计结合自然》。这本书出版于1969年。在20世纪80年代,风景园林学科逐渐从关注静态模型转变为关注动态变化。您怎样看待这个转变呢?

2~4旧金山烛台角文化公园Candlestick Point Cultural Park, San Francisco

George:对我来说,《设计结合自然》是一本关于发展的书。麦克哈格在书中展示了千层饼法,它可以帮你判断哪些土地适宜发展。这仍然是个静态模型。真正结合了自然过程的设计与这本书不见得有必然联系。我认为这个转变开始于学术界:当人们在阅读和思考书中的内容时,产生了关于是否能把自然过程纳入设计的讨论。我也是从那时介入这个议题的,我尝试用地形去表现自然的过程,让静态的物质空间和自然的动态变化在人的体验中统一。

LA:我们聊到了生态。关于生态设计,目前有很多影响深远的理论,比如景观都市主义。不过,在理论和实践之间仍有一道鸿沟。当你实地参观一些在这些思想指导下的大型项目时,你可能很难把眼前的空间和背后的理论相联系。您怎么看待这个问题?

George:我觉得景观都市主义很有趣,不过我见过的一些已建成的项目确实差强人意。我记得有个废弃机场(更新)项目,风景园林师在那里种了很多树,希望景观的改变会引导机场的发展。不过,如果你去了那儿,你会发现树都不见了。所以我对于景观能成为发展的引擎这个想法是有些怀疑的。不管尺度大还是小,每个项目都应包含独特的体验。仅仅一块湿地或者一片森林是不能被算作一个项目的,它们也未必会带来地区发展。说到这儿我们又回到了我的“三角形”—一个项目必须能引起共鸣。我们也做过一些大尺度的,创造性地表现自然过程的项目,不过在那些项目里我们也设计了像是儿童游乐场或者野餐区之类的地方。这些地方是让人们和自然发生实质性的互动的地方(图5、6)。

对于景观都市主义,也许我们还没有找到很好的方法去实践它。弥合理论和实践的鸿沟需要大量的工作。想个点子、画画草图是很容易的事情,但把它们转译,让它们落地,非常困难。在我们的工作中,我们尽最大的努力将想法变成现实。

LA:您是否觉得,结合自然去设计并非因为这是必需,而是因为如果我们顺应自然,我们就可以在后期维护上节省功夫呢?

George:设计结合自然并不等于你要顺应自然。阿姆斯特丹森林(图7)是彻头彻尾的人造景观,人们挖掘水渠、排出地下水,并种植森林。从这个角度看,设计结合自然也意味着为了你的目标而驾驭自然。

LA:荷兰的土地天然平坦又含水过多。那里的人们必须改造自然,从而让土地适宜居住。那么,结合自然的设计是否存在文化差异呢?

George:也有地理特征的差异。你没法把阿姆斯特丹森林和瑞士的群山等同考虑,因为你得关注场地。这就是为什么我有三角形理论—对我来说,因地制宜、经济可持续和易被铭记的确是成功项目的关键驱动因素。

5 伦敦伊丽莎白女王奥林匹克公园鸟瞰Bird-view of Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park, London

6 伦敦奥林匹克公园局部鸟瞰Bird-view of Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park, London (partial)

LA:您在世界各地都有项目,这些项目的背景和条件各不相同。在一个陌生的环境中,您如何开始呢?您怎样去了解这些场地呢?

George:我们的大多数项目都是公共空间,从这个角度看它们是有共通之处的。不过,在基本的相似性之上,我们会挖掘那些独特背景和文化,这对我来说至关重要。当我们开始天津塘沽(海河带状公园)项目的时候,我在周边走访,观察人们如何使用公园和开放空间。我们发现他们和西方人的使用方式是完全不同的。西方的公园里通常有很多开放草坪,人们在草地上野餐或者休息。但中国人不这么做,他们在公园里走来走去。所以我们在塘沽只做了很少的空旷场地。我们种了一排又一排的树,并让小路在树林间穿梭。这和我们在美国处理设计的方式大相径庭(图8、9)。

LA:您曾参与多个地区的棕地项目,您觉得中国的棕地问题和其他地区的有什么不同吗?

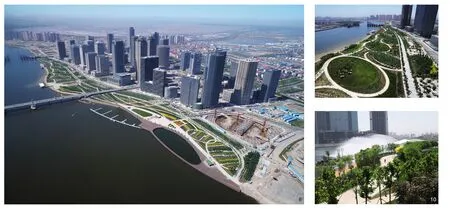

George:事实上我认为这些问题越来越趋于相似。中国在过去30年做的事,在美国大概需要100年完成。棕地当然有不同的类型,比如天津海河项目是高度盐碱化的土地(图10),而伦敦奥林匹克公园的土地堆积了“二战”期间爆炸残留物,污染严重(图11、12)。首先,你要了解你在处理什么,这不难。难的是寻找创意。如果你的场地是湿地或者山地,你一开始就有借力之处。在一片平坦的废弃地上,你很难找到设计线索。所以我们又回到了三角形理论,回到场地—你在哪儿?伦敦项目和海河项目的不同之处不在于棕地类型,而在于它们处在完全不同的文化中,要实现的目标也完全不同。伦敦奥林匹克公园是欧洲21世纪以来最大的公园。海河项目则是要为未来新城发展塑造滨水空间。这意味着(设计的)语境很重要。

对所有项目,你都得有一个清晰的概念去统领。在伦敦,这个概念是拓宽河流并让人们走近它、亲近它。当我们有了这个概念后,我们想到了要设计高耸的地形,这样人们就可以在远处看到并被吸引。在海河项目中,我们得保证这个1km长的滨水空间在人流稀少的情况下维持10~15年仍旧保持良好风貌②,因此我们在整个项目中使用了大量树木。

LA:项目建成后你会回访吗?当你回访的时候,它们是否如你预料一般地发展呢?

George:我总是回访,特别是我们在附近有什么新项目时。

有时候,我们的客户和我们在管理和维护上有不同想法。我们曾在某滨河项目中设计了引水口,但客户讨厌它。客户表示那看起来很糟糕,因为河水带来了上游的垃圾和杂物。我们还曾设计了不需修剪的由本土植物组成的草地,但客户觉得那是杂草。在另一些情况下,有些我们设计的项目就是没能吸引人来,或者是人们的实际使用方式和我们的预计完全不同。

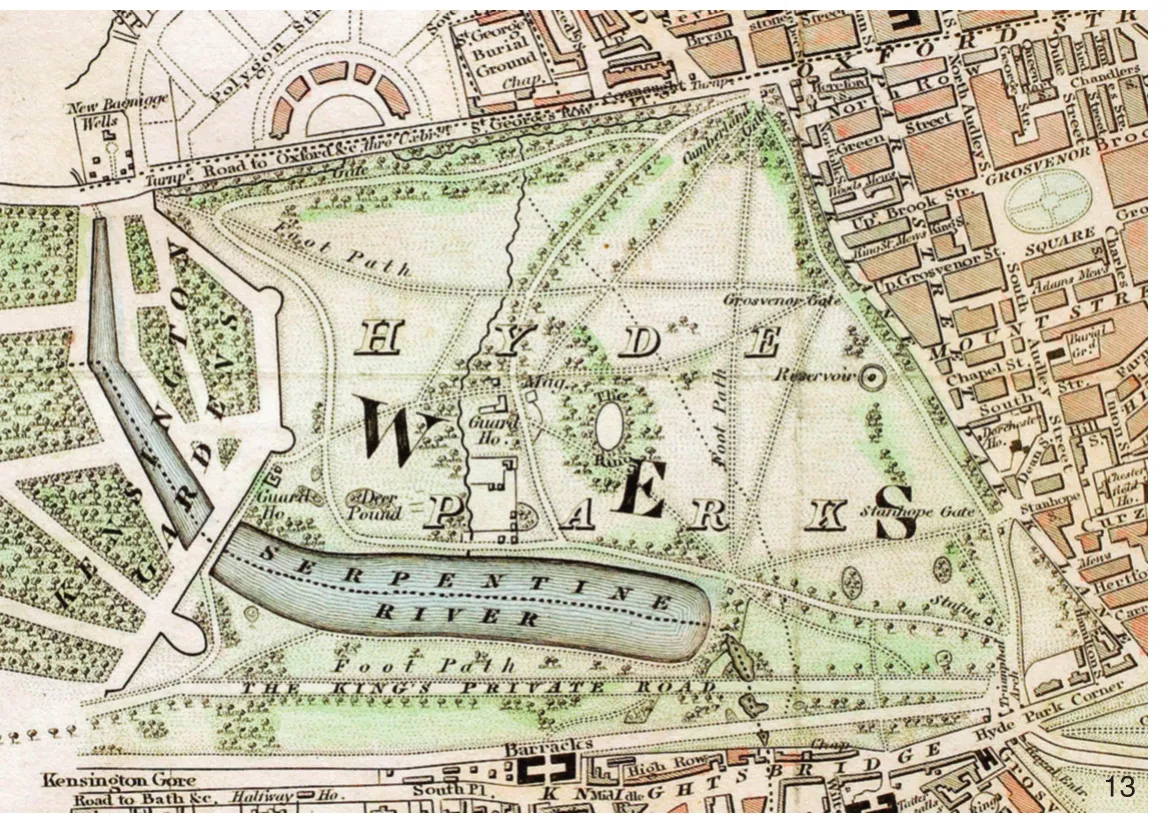

7 阿姆斯特丹森林Amsterdamse Bos

我对设计“大”的景观更感兴趣—为自然和人设计容器。当人们想要个更大的儿童游乐场或者音乐会场时,都是可以满足的。就像海德公园(图13~15),在18世纪初曾塞满了当时时髦的各种功能,但今天这些功能都不在了。今天流传下来的是景观的“骨架”:水道、树林,等等。你甚至不知道历史上曾经发生过什么。在我自己的项目中,我试图尽可能摆脱具体的功能。对公共项目来说这很难,因为人们通常更关心到底游乐场在哪儿,而很难理解总体上的“骨架”。游乐场在哪里也重要,不过如果你考虑的是100年的时间尺度的话,(具体的功能)就没那么重要了。我们越是能把自然景观本身打造得生机勃勃,它们越是能扛过糟糕的后期维护、不断变化的使用需求,并经受住时间的考验。

LA:这样讲来,您提到控制所有细节是不可能的,最重要的是控制总体的景观“骨架”。这具体指什么呢?

George:说到“骨架”就不得不提我们的老朋友了:水体、地形、排水、植物材料、场地的质感……对我来说它们真的很重要。我总是从自然景观出发,再考虑具体的功能如何排布。很多人会采取相反的方法,像建筑师那样先进行功能布局。我尝试另一种方法:通过组合基本元素,为多种可能的功能留出空间。

LA:您在近期工作中的关注重点是什么?

George:我们正在做越来越多的公园,和越来越多的小尺度项目(图16~18)。2019年北京世园会的展园是一个很好的例子。此外我们最近出版的新书名为《景观和花园》,它的名字阐释了我们的兴趣:强调让景观回归“景观”,回归水体、地形等基本元素。

LA:在您看来,未来10年风景园林的发展趋势是什么呢?

George:我认为在城市空间的建成环境中会有很多机会,并且人们对此抱有厚望。年轻的设计师或许会发现,即便我们有了迷人的理论,也不见得能把它们变成我们想要的空间,或者是有人愿意花100万美元去维护的地方。在你着手工作前,你需要理论支撑,也需要关于项目的具体概念。首先想想什么能落地,再回去想想那背后的理论。你可能会修正理论,也可能会修改设计。这是我擅长的事情:如果一条路走不通,那就试试别的。我不会被正在进行的工作困住。如果你的方法不灵的话,那一定是有原因的。

注释:

① 烛台角文化公园地区原有岸线陡峭,少有平缓海滩(张博雅注)。

② 公园建设时其周边城区还未开始建设(张博雅注)。

③ 图1由张博雅根据哈格里夫斯讲座幻灯片改绘;图2~6、8~12、16~18由哈格里夫斯提供;图7 引自urbancaptures.com;图13引自维基百科;图14引自maps.google.com;图15由张博雅摄。

(编辑/王一兰)

What kind of design is ‘ecological’? Landscape architects must answer this issue, since ecological restoration has become a national policy. In China,ecological design often reminds people of untrimmed vegetation, habitats for animals, etc. However, does a natural look mean ecological design? In professional practice, designers lack a certain design language to tackle with the ecological issue. In this field, our European & American peers have started exploration earlier than us. Therefore, knowing their experience is signi ficant to Chinese designers.

George Hargreaves is one of the most famous landscape architects in America. We are glad to have this discussion on ecological design and the design philosophy of Hargreaves Associates with him. He grew up in 1960s and 1970s in America, which is an era when the ecological ideology was born and developed.He has engaged in brownfield transformation projects since the 1980s. He was inspired by land arts by that time, and applied the idea in landscape design innovatively. He has designed many vital projects worldwide, including Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park, London. He has made a profound contribution to the theory and practice of large parks and brownfield transformation. In 2016 Hargreaves Associates was the recipient of the Cooper Hewitt National Design Award as well as the Rosa Barba International Landscape Prize.

LA: Landscape Architecture Journal

George: George Hargreaves

LA: Let’s start from the very beginning.It is said that your initial interest in landscape architecture was inspired by a trip to the Rocky Mountains. What inspired you in that trip? What convinced you to pursue landscape architecture after that trip?

George: Discovering the landscape was inspiring. When I was hiking, I noticed the vegetation was changing with altitudes. The plants on top were very different from the ones at the bottom,that was novel to me at that time. I was interested in the landscape itself and its spatial quality. Initially I thought I could study forestry. My uncle worked in University of Georgia at the time, and he suggested to me to look into landscape architecture. When I visited the school, people there were doing parks. I thought, yeah, I want to do this.

8~10 天津海河带状公园Haihe River Ribbon Park, Tianjin

LA: You have a ‘triangle theory’ about design: SITE, SUSTAINABILITY, and MEMORABILITY(Fig.1). It seems to be the basis for conceptual thinking in all your projects.What does this triangle mean to you? And why memorability is so important?

George: I’m always interested in the site.I thought there should be a site-specific quality in design. About sustainability, many people take it from an ecological point of view, but I also consider it from an economic point of view. I was very impressed by many old parks and gardens,specifically Hyde Park, and St James Park in London. However, considering people have spent fortunes to maintain them for hundreds of years, in this instance, sustainability means somebody has to pay and maintain it. Then it comes to memorability.When a park is memorable, it speaks to people.People take something from it. If you only make something ecologically sustainable but not memorable, and people take nothing more than the idea of sustainability, you failed. By making the site memorable, you attract people to want to sustain it.

LA: That’s true. Your works are highly memorable. People recognize them by sculptural landforms. What inspires these forms?

George: I started working with landforms in graduate school. At that time landscape architects often worked with geometries in plan. I was really trying to find another way to develop landscape.I was inspired by some historical landscapes and started doing projects that didn’t have any plans.All I had was landforms. One of the first projects I designed after graduate school was a 25hm2landfill with only a half million-dollar budget,meaning we could only do one thing there. You could either plant trees all over, or make it grassy.In the end, landform became a way to design large projects that didn’t have money.

LA: In that sense working with landforms was very innovative in 1980s. Is this also the point you began working with brownfields?

George: I was one of the first landscape architects who worked primarily with landforms. I was inspired by artists like Robert Smithson. The difference was that my works were meant to be interacted with as public space, while of the majority of contemporary landform artworks were built in desert, and meant to be looked at from outside.

To some extent, brown fields chose me at that point. In the beginning I had a very small office.While large landscape firms were doing gardens for developers, I had different clients. The people who came to us didn’t have a lot of money, and they had a problem. They had a garbage dump or land fill, and they thought we had creative solutions that didn’t necessarily cost a lot of money. So, in the scenario we found ourselves in, you just gotta do the best you can, right?

My approach is still a work in progress. It took me years realize that not every project is a landform project. I started working more with plants, etc. And at this point, I would say landform is an even aspect of our projects, balanced with a full repertoire of tools & design elements.

11、12 伊丽莎白女王奥林匹克公园,伦敦Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park, London

LA: You to mentioned that landforms are connected to natural processes. How does that work in your projects?

George: Well, I’m not an artist. I think a landform on its own it’s not a project. I started trying to marry landforms and natural process, to try and let landforms accentuate natural processes.In Candlestick Point Cultural Park, we tried to work with strong winds and tides in San Francisco Bay Area. Our landforms work with the visceral action of the wind. While walking through it, one can experience a range of exposures to wind—from strong winds through to being sheltered. We created inlets to let tides come in and out, exposing the vertical fluctuation of the tide, horizontally. The tides had,and will always there but now you can register these processes in ways that you couldn’t see before①(Fig. 2-4).

LA: Speaking of working with natural process, we can’t miss Ian McHarg’sDesign with Nature. It was published in 1969. In the 1980’s,the focus of the profession gradually shifted from static models to dynamic natural processes. How do you consider this transition?

George: To me,Design with Naturewas a book about development. He showed a layering system that uncovered where you could develop and where you couldn’t. It was still a rather static model. There is probably no natural connection between his book and working with natural processes in landscape design. I think the transition came out from the academic world. When people read and digested the book, it generated discussion about the possibilities of designing with natural processes. That was also where I came to the conversation, where I was trying to make landforms that expose natural process, and connect both the physical and ephemeral as part of a uni fied experience of landscape.

LA: And now we come to the ecology issue. There are many profound contemporary theories about ecological design such as landscape urbanism. However, there is a gap between theory and practice. When you visit large scale projects that embraced these theories in design in person, it might be hard to connect the space with its theoretical underpinning. What do you think?

George: I think landscape urbanism is very interesting, but the built examples I’ve seen don’t stand up. There is a project where the landscape architect planted a lot of trees on an abandoned airport and the idea was that development would take place gradually. However, when you go there now all the trees are gone, so I became suspicious about the idea that landscape can be an agent of change. Be it a large-scale project or not, there should be a certain experiential quality to it. A wetland or a forest itself is not a project, and they don’t necessarily drive development. And, here is where I returned back to the triangle. A project must be memorable. We’ve also done several large-scale projects creatively designing with natural processes, but within those same projects we also designed picnic areas and children’s playgrounds— these are elements that landscapes also need to have to engage the public (Fig. 5, 6).

Perhaps we haven’t found a proper way to work with theories like landscape urbanism. Bridging the gap between theory requires a lot of work.It’s easy to come up with an idea and make sketches, but it’s hard to downshift the idea into a built landscape. We are trying to bring these two together as much as we can in our work.

LA: Do you think the interest in working with natural processes is not because we need to, but because the outcome might require less effort to maintain if we follow what nature does?

13 海德公园,1833年Hyde Park, 1833

14 海德公园现状卫星鸟瞰Aerial view of Hyde Park nowadays

15 海德公园Hyde Park

16~18 斯坦福大学庭院Stanford University Science and Engineering Quad

George: Working with natural process doesn’t mean you need to follow them. Amsterdam Bos(Fig. 7) is a completely made landscape. People dug the canals for drainage and planted the forest. In this sense it could also be about harnessing natural processes for the ambition you have for the landscape.

LA: Dutch landscapes are naturally wet and flat. People there must work the land to make it livable. Is that maybe a cultural difference to working with natural process?

George: There is also a difference in geology.You can’t conceptualize the Amsterdam Bos in the context of the mountains in Switzerland. You need to look at the site. That’s why I have the triangle.Site, sustainability, memorability. To me, these 3 things really drive a successful project.

LA: You have projects worldwide, and they are all in different contexts and deal with different conditions. How do you start working in an unfamiliar environment? How do you get to know your site?

George: Most of our projects are public open spaces, so in that sense they have something in common. But building from that baseline similarity,we also educate ourselves about the specific context and culture. To me that’s an important aspect. When we started in Tanggu, Tianjin, I looked around to see how people typically use parks and open space. We found that they were using it in a way very different from westerners.You have a lot of open grasslands in western parks,and people picnic or lay on the grass. Chinese don’t do that. They promenade through landscapes. So,in Tanggu, we did very few open areas. We planted a lot of trees in rows, and let the pathways go through the trees. That’s a very different approach to our projects in the US (Fig. 8, 9).

LA: You’ve worked on brownfields in many places, do you think there is a difference between the issues in China and the issues elsewhere?

George: Actually, they are becoming very similar. What China has done in the last 30 years might take US 100 years to do the same. There are of course different types of brown fields. Like in Haihe it was dealing with highly saline-alkali soil (Fig. 10),and the London Olympic Park grounds remained as a filled, polluted, contaminated and bombed remnant landscape left from WWII (Fig. 11, 12). You first need to know what you are working with, and that’s the easy part. The hard part is, finding the idea. If you’ve got a wetland or a hill, you’ve already got something to work with. On a flat and degraded site there are little clues to work with. Here we come back to the SITE—where are you? The London project is different from Haihe project. That’s not because they are different types of brownfields, but because you are in a different culture, people have different ways of using landscape. And there are totally different objectives in the projects: London Olympic park became the largest park built in Europe in the 21st century; Haihe is more about shaping the waterfront to shape and encourage the development and the City behind it. Site matters.

You need to have a conceptual driver for all projects. In London, the driver was expanding the river to let people get down to it. As we figured that out, we came up with the idea of plateaus where you can really see the park from a distance.In Haihe, the idea was figuring out how to make a 1km long waterfront stay endure as an amenity for the first 10 to 15 years without people②.

LA: Do you revisit your projects after completion? When you do, have they worked out as you expected?

George: I always go back, especially if I’ve got a new project nearby.

Sometimes the clients who manage them have different ideas than what we had regarding management and maintenance. We had a riverfront project where we created inlets for water to come in and out, and the clients hate it. They said it doesn’t look good because the water brings garbage and other debris from up-river. We also had an untrimmed native meadow somewhere else on the site, and the client said it looked like weeds. In other instances, some of the program just didn’t work out, and/or people just don’t end up using it the way we thought.

I’m more into how to do the big landscapes—how to design a vessel for both natural processes,and human. If somebody wants a bigger playground or a concert area, that’s fine. Just like Hyde Park(Fig.13-15), it used to be a highly programmed park with 18th century attractions. But if you go there today the programs are all gone. What you still have is a beautiful framework of the landscape:the watercourses, the trees, etc. You don’t even notice what happened in history. If you look at my own work, I try to not get caught up in program as much as I can. Although, it’s very difficult in a public project. It’s hard to let people understand the overall idea when they care more about where the playground is located. That’s also important to some degree, but if you take 100 years, it’s not that important… The more robust the landscape that we can make, the more it will stand up to poor maintenance, bad detailing, and changing use needs,in order to endure the test of time.

LA: Building on that, you said it not possible to control all the details, it’s more important to control a framework for the overall landscape. What do you mean by that?

George: By that we came back to our old friends: water, gradient, drainage, plant materials,and the texture of the surfaces. To me that is what is really important. I always start with the landscapes, and think where the programs might go. Many people approach design opposite, it in an architect mindset where they first figure out the programs. I try to put it the other way. By working with basic elements, you make room for the possibilities of programs.

LA: What is your recent focus in your work?

George: We are doing more and more urban parks, and doing more and more smaller projects(Fig. 16-18). The garden in the Beijing Expo 2019 is a great example. Furthermore the newest book we recently published is calledLandscapes and Gardens—where its name represents our interest in addressing the importance of making landscapes simply as landscape.

LA: In your perspective, what is the trend in landscape architecture in the next decade?

George: I think there are many opportunities for future built landscape in urban areas that people have high hopes for. The younger generation of designers might discover, even if we have a beautiful theory, they don’t always materialize as a landscape we want go to, or similarly not as a landscape somebody wants to pay 1 million dollars to maintain.You need to have both a conceptual basis for the project, and also the theory behind it, before you can work it through. Think about what’s on the ground first, and work it back up to the theory. You may change the theory, and you can change the concept.That’s what I’m good at. If something doesn’t work,then we try some else. I don’t get stuck on any one thing we are doing. If it’s not working, there is a reason why it’s not working.

Notes:

① The original sea shore of Candlestick Point Cultural Park was very steep. There was almost no gentle slope (Noted by ZHANG Boya)

② The park was built before the surrounding neighborhood(Noted by ZHANG Boya).

③ Fig. 1 ZHANG Boya redrew it according to Hargreaves’s lecture slides. Fig. 2-6, 8-12, 16-18 are provided by Hargreaves Associates; Fig. 7 Source: urbancaptures.com;Fig. 13 Source: Wikipedia; Fig. 14 Source: maps.google.com; Fig. 15 is photographed by ZHANG Boya.