Effects of Praseodymium Doping on Conductivity and Oxygen Permeability of Cobalt-Free Perovskite-Type Oxide BaFeO3−δ

Bng-zheng WeiYu WngMeng LiuChen-xi XuJi-gui Cheng

a.School of Materials Science and Engineering,Hefei University of Technology,Hefei 230009,China

b.Key Laboratory of Advanced Functional Materials and Devices of Anhui Province,Hefei 230009,China

I.INTRODUCTION

Fossil energy is still the major energy sources in current industrial production,such as coal,oil and natural gas,etc.,and enhancing its utilization efficiency and reducing emissions of polluted gases have become one of the most imperative requirements in energy and environment areas.Using oxygen enriched air or pure oxygen instead of air as oxidizer combustion is one of the effective ways to meet the needs.However,the traditional oxygen production processes,such as cryogenic separation and pressure swing adsorption have some disadvantages,including high production cost and low purity of resultant[1,2].As a new oxygen production technology,separating oxygen from air by ceramic membranes has shown to be a promising process due to the advantages of without additional circuitry required and high oxygen selectivity of about 100%[3,4].

Perovskite-type(ABO3)materials with mixed ionic and electronic conductivity(MIEC)have attracted enormous attentions in oxygen permeable membranes[5–7].Since the reports of the high oxygen permeability of La1−xSrxCo1−yFeyO3−δby Teraokaet al.[8],many cobalt-based perovskite-type oxygen permeable membranes have been developed,e.g.SrCo0.8Fe0.2O3−δ[9,10], Ba0.5Sr0.5Co0.8Fe0.2O3−δ[11,12], SrCoxNb1−xO3−δ[13,14], BaCo0.7Fe0.3−xNbxO3−δ[15,16],60wt%Ce0.9Gd0.1O2−δ-40wt%Ba0.5Sr0.5Co0.8Fe0.2O3−δ[17].However,cobalt-based perovskite-type oxides may be not favorable for practical uses because of their relatively low stability under harsh conditions due to the evaporation and reduction of cobalt[18,19].To overcome this drawback,some cobalt-free perovskitetype materials have been developed to use as oxygen permeable membranes.Bene fiting from the less flexible redox behavior of iron,Fe replacing Co as B-site ions in the ABO3perovskite-type materials has been investigated.Among the ferrum-based perovskite-type materials,BaFeO3−δhas high oxygen permeability because Ba can expand the lattice free volume and lower the average metal-oxygen bond energy in the lattices[20].Nevertheless,Ba has a large ionic radius,which results in a phase transition of the BaFeO3−δmaterials as temperature decreases[21].At high temperature,the crystal structure of BaFeO3−δmaterials is cubic phase,however,at low temperature,which probably transforms to hexagonal,tetragonal,triclinic,etc.[22].Cubic phase provides a large channel for oxygen ions transmission in their interior due to the relatively open space,moreover,the equivalent positions of which are the most,that conducive to the migration of oxygen ions.Thus,in the same material system,the cubic perovskite structure has the highest oxygen permeation flux.Ramadass introduced the concept of tolerance factor(Ft)to characterize the stability of cubic perovskite structure[23]:

WhererA,rBandrOare radii of A,B site ions and oxygen ion,respectively.It is usually considered that the material can keep the ideal cubic structure when 0.95<t<1.04[24],and thetof BaFeO3−δis calculated to be 1.066,which is beyond the established range.

Previously,several reports have shown that it is feasible to stabilize the phase of BaFeO3−δwith cubic perovskite structure at low temperature by partial substitution of A or B site ions,such as these in Ba0.95La0.05FeO3−δ[25],Gd0.33Ba0.67FeO3−δ[26],BaFe1−yTayO3−δ[27],BaNbyFe1−yO3−δ[28]and BaFe1−yCuyO3−δmaterials[29]. The ionic radii of Pr3+and Pr4+were 0.99 and 0.85˚A,respectively,which are slightly larger than that of Fe3+(0.55˚A)and Fe4+(0.585˚A)of B-site ions,meanwhile,much smaller than that of Ba2+(1.61˚A).Therefore,in this paper,Prn+were selected as the doping ions to partial substitute Fem+in BaFeO3materials,and the in fluences of partial substitution on the crystal structure,microstructure,electrical conductivity and oxygen permeability of BaFe1−yPryO3−δhave been systematically investigated.

II.EXPERIMENTS

A.Samples preparation

BaFe1−yPryO3−δ(y=0,0.025,0.05,0.075,0.1)powders were synthesized by the solid state reaction method in which BaCO3,Fe2O3,Pr6O11powders were weighed according to stoichiometric ratio,after ball-milling with zirconia media in absolute alcohol for 20 h,the dried powder mixes were pressed into block,calcined at 1100°C for 5 h in air,and then ball-milled for 10 h to obtain BaFe1−yPryO3−δpowders.In order to characterize the electrical conductivities,oxygen permeation fluxes and some other performance of the prepared materials,the synthesized powders were pressed into green bars and disks under a pressure of 150 MPa,respectively,and subsequently sintering in air at 1300°C for 5 h.The surface of the sintered samples were then polished with an emery paper(80)to adjust the dimensions of sintered bars with of 4 mm×5 mm×10 mm and thickness of disks with 1.0 mm.

B.Characterizations

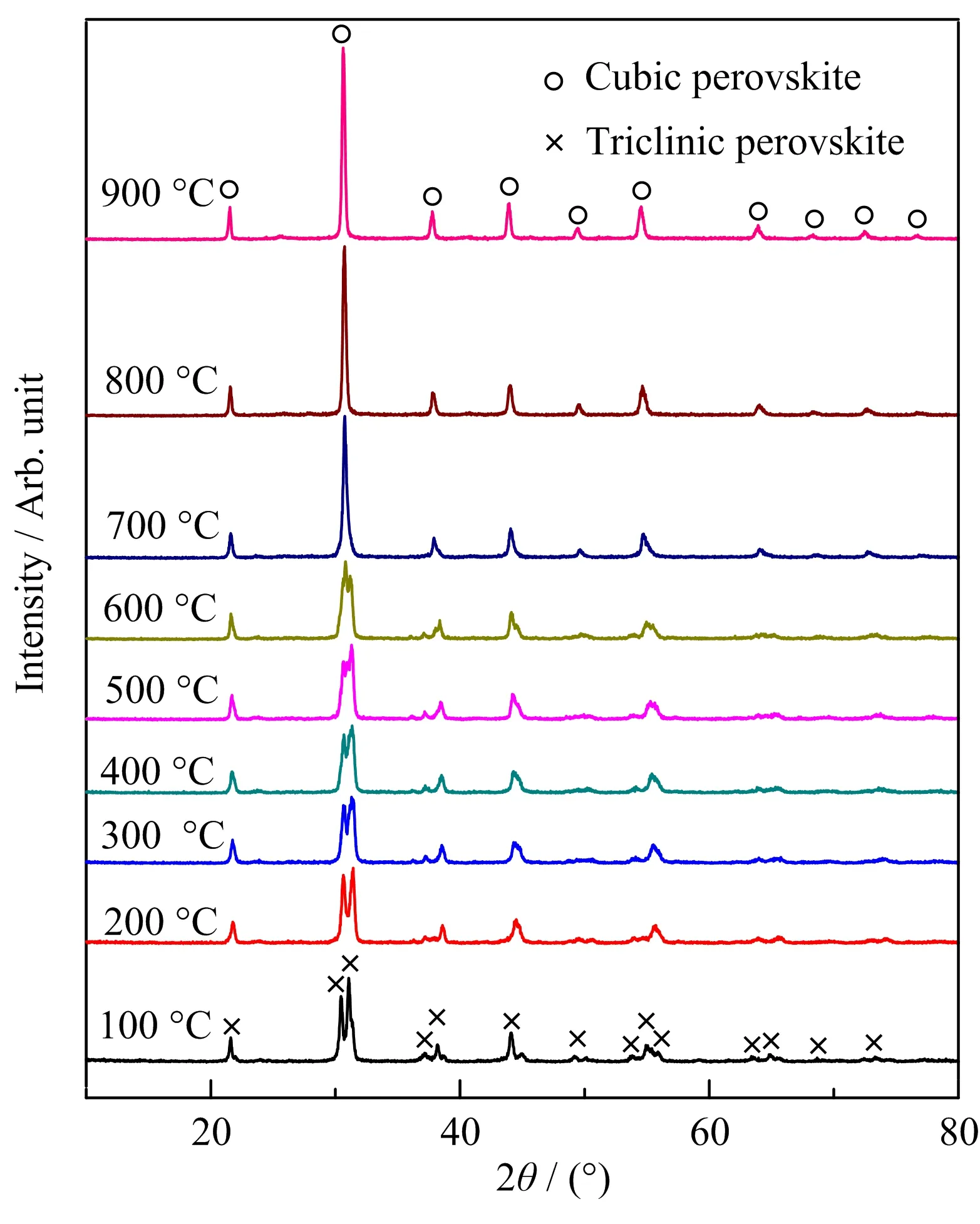

Relative densities of the sintered samples were measured using the Archimedes’method.The crystal structures of the BaFe1−yPryO3−δpowders at room temperature were characterized by X-ray diffraction(XRD D/MAX2500V)using CuKαradiation,with diffraction angles of 10°≤2θ≤80°at an interval of 0.02°. The crystal structures of BaFe0.975Pr0.025O3−δmembrane were characterized by a high-temperature X-ray diffraction(HT-XRD),the temperature was slowly increased from room temperature to 100,200,300,400,500,600,700,800,900°C and maintained constant at each designated temperature for 30 min before measurements were taken. The elemental compositions of BaFe0.975Pr0.025O3−δpowders was analyzed by energy dispersive spectrometer(EDS).The surface and cross section morphologies of BaFe0.975Pr0.025O3−δand BaFe0.925Pr0.075O3−δdisks were examined by scanning electron microscope(SEM,JSM-6490LV).

C.Electrical conductivity measurements

The electrical conductivities of the BaFe1−yPryO3−δbars were measured using a four-probe DC method between 300 and 900°C at an interval of 50°C.Silver paste and silver wire were used as current collector and current wire,respectively.A constant current was applied to the two current wires,and the voltage responseσon the two voltage wires was recorded by Digital Multimeter(U3606A),the electrical conductivity was calculated according to Eq.(2).

WhereLis the length of the two voltage contacts,RandSare the resistance and cross-sectional area of BaFe1−yPryO3−δbars,respectively.

D.Test of oxygen permeability

The oxygen permeation flux of BaFe1−yPryO3−δmembranes were tested using a homemade apparatus,described in our previous work[30].The membranes were sealed onto an Al2O3tube using a commercial ceramic sealant(Yihui,Hongkong).Within test temperature range of 600−950°C,the feed side of membranes was exposed to atmospheric air,whilst a 100 mL/min flow of helium was fed with the permeating side to provide the oxygen partial pressure.Flow flux of the helium was controlled by a mass flow controller(D08-1F).

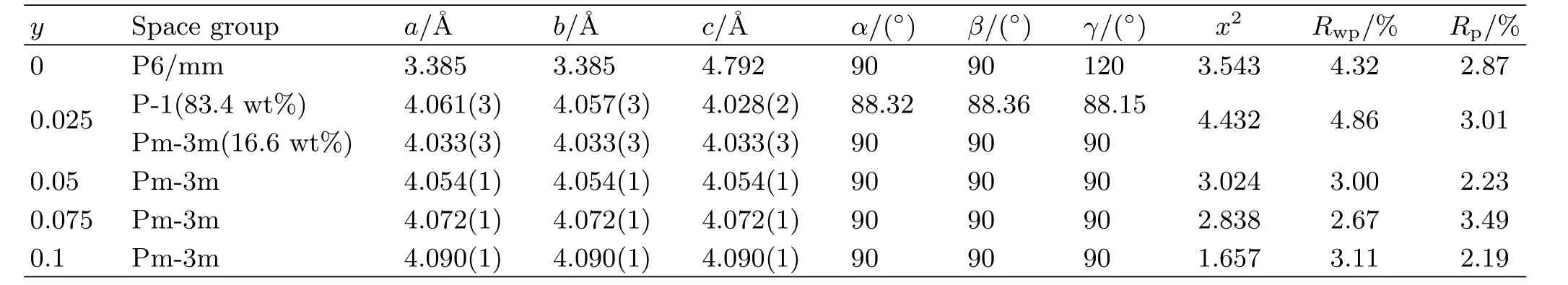

TABLE I Structural parameters of BaFe1−yPryO3−δ powders at room temperature.

The content of O2and N2in the permeation gas were analyzed by the gas chromatography,where N2is the leak gas.The effect of leakages can be estimated using Eq.(3)to calculate the oxygen permeation flux:

WhereCOandCNare the measured gas phase concentrations of oxygen and nitrogen in the sweeping gas,fis the flow flux of the exit gas on the sweep side,andSis the effective oxygen permeable area of the oxygen permeable membranes.

III.RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

A.Characteristics

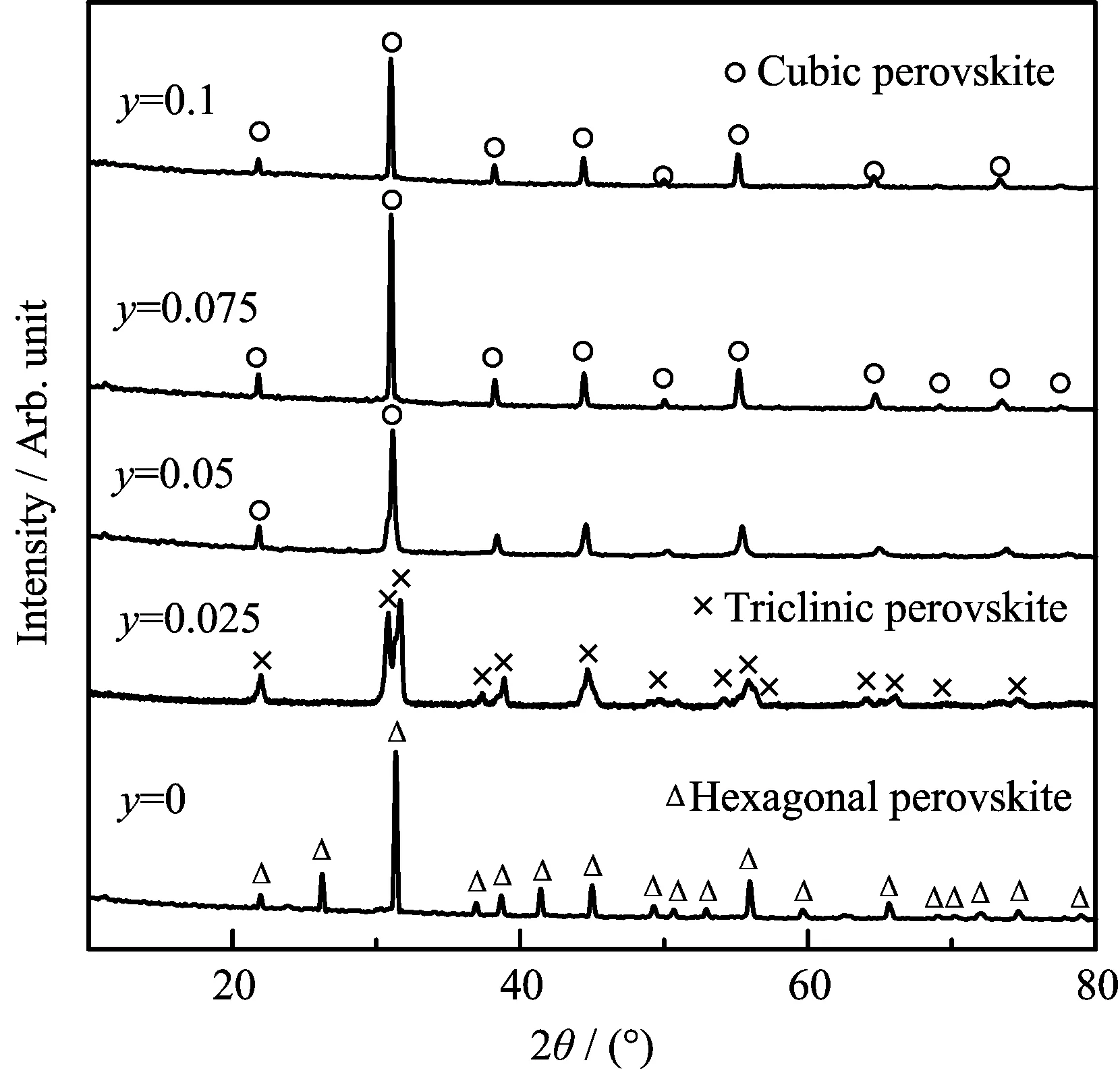

FIG.1 shows X-ray diffraction patterns of the BaFe1−yPryO3−δpowders with different praseodymium doping amount at room temperature.The main peaks were shifted to lower angles with the increasing of the substitution amount(y)in BaFe1−yPryO3−δ,indicating that the lattice constant increases as doping more praseodymium into the B-site. Moreover,no crystalline phase of praseodymium oxide was detected from the XRD patterns,suggesting that the praseodymium were successfully doped into the oxide lattice of BaFeO3−δ.Table I lists structural parameters of BaFe1−yPryO3−δpowders at room temperature.It is shown that the crystal structure of the parent BaFeO3−δis hexagonal,which is consistent with other reports[26,28].When the substitution amounty=0.025,BaFe0.975Pr0.025O3−δfailed to stabilize the cubic structure but formed a triclinic phase together with the cubic phase[31].In contrast,cubic structure forms at a substitution amount ofy=0.05,0.075,0.1.The tolerance factor of the BaFe1−yPryO3−δmaterials decreases from 1.066(y=0)to 1.045(y=0.1)with the increase of the substitution amount(y).The results show that doping Prn+is bene ficial to stabilize the cubic perovskite structure of BaFeO3−δoxygen permeable membranes at room temperature.

FIG.1 X-ray diffraction patterns of the BaFe1−yPryO3−δ powders at room temperature.

FIG.2 shows point scanning analysis patterns of BaFe0.975Pr0.025O3−δpowders,only Ba,Fe,Pr,O were detected.Table II lists the theoretical and trial percentage of elements of BaFe0.975Pr0.025O3−δpowders,respectively.The results show that the powders synthesized by the solid state reaction method have good composition stability.

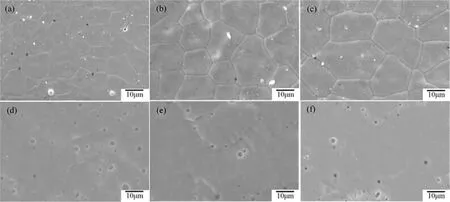

FIG.3 showsSEM photographsofthesurface and cross section of un-doped BaFeO3−δ,BaFe0.975Pr0.025O3−δand BaFe0.925Pr0.075O3−δmaterials.The surface of all membranes are dense with clear grain boundaries,the cross section contains a small amount of closed pores.The compact structure ensures the purity of separated oxygen. The grain size of BaFe1−yPryO3−δincrease monotonically with the increase of the praseodymium doping amount,the detail of grain size effects on the oxygen permeability has not been understood well. However,there are different opinions on whether the increase of grain size is beneficial to the improvement of oxygen permeability[32].

FIG.2 SEM photograph(left)and EDS spectrum(right)of the BaFe0.975Pr0.025O3−δ powders.

FIG.3 SEM photographs of the surface(top)and cross section(bottom)of membranes. (a,d)BaFeO3−δ,(b,e)BaFe0.975Pr0.025O3−δ,(c,f)BaFe0.925Pr0.075O3−δ.

TABLE II Atomic percentage of elements in BaFe0.975Pr0.025O3−δ.

B.Conductivity properties

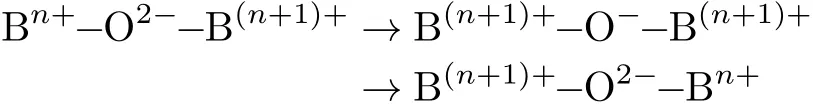

FIG. 4 shows electrical conductivities of BaFe1−yPryO3−δbars at temperature intervals from 300°C to 900°C.Below 750°C,the electrical conductivity of parent BaFeO3−δis low,and then increases sharply,implying that there probably exists a phase transition around the temperature.With a small amount of praseodymium doping(y=0.025),the temperature of obvious increase of the electrical conductivity for BaFe0.975Pr0.025O3−δadvances to 600°C.Due to the cubic structure that is beneficial to the carrier transmission forms with a larger praseodymium doping amount(y=0.05,0.075,0.1),the specimen bars also have high electrical conductivity at low temperature. Moreover,under all test temperature,the electrical conductivity increases with the increase of doping amount,and maximum electrical conductivity reaches 6.5 S/cm for BaFe0.9Pr0.1O3−δat 900°C.The electrical conductivity in the perovskite oxides is generally created by electron hopping along the B-site lattice cations and oxygen ion through strongly overlapping B−O−B bonds with a mechanism known as the Zerner double exchange:

FIG.4 Electrical conductivity of BaFe1−yPryO3−δ between 300 and 900°C.

The stabilization of cubic lattice structure of BaFe1−yPryO3−δis strengthened with the increase of the praseodymium doping amount. The cubic perovskite phase can maximize the overlapping of the electron clouds between O2and Fem+ions,thus facilitate the electron conduction[28]. Prn+has a variable valence state,which lets it participate in the Zerner double exchange.It should be noted that,at temperature above 550°C,the electrical conductivity of the materials decreases with the increase of temperature.That may be ascribed that the BaFe1−yPryO3−δmaterials are p-type electronic conductors,and the conductivity increases with increasing temperature.However,more oxygen vacancies will be formed inside the materials at higher temperature,but the formation of an oxygen vacancy consumes 2 times electron hole,thus reducing the electrical conductivity[33].

C.Oxygen permeability

FIG.5 shows oxygen permeation fluxes of the BaFe1−yPryO3−δmaterials as a function of temperature.With praseodymium doping in B-site,the oxygen permeation fluxes of all membranes were higher than that of the parent BaFeO3−δ,particularly at lower temperature around 600−750°C.In addition,the oxygen permeation fluxes increase with the increase of praseodymium doping amount,and the maximum oxygen permeation flux reaches 1.112 mL/(cm2·min)for BaFe0.9Pr0.1O3−δcomposition at 900°C,which is consistent with the increase of conductivity.However,at temperature below 650°C,the oxygen permeation flux of BaFe0.975Pr0.025O3−δmaterials is low,and above 650°C,it increases sharply,implying there probably exists a phase transition around the temperature.To elucidate the reason for this,the crystal structure of BaFe0.975Pr0.025O3−δmembrane with the change of temperature was characterized by high temperature X-ray diffraction(HT-XRD).

FIG. 6 shows HT-XRD patterns of BaFe0.975Pr0.025O3−δmembrane atdifferenttemperature.The membrane is triclinic phase at 100°C,which is the same as that measured at room temperature. With the increase of temperature,the crystal structure of the membrane gradually changes into cubic phase,and completely transforms into a cubic phase above 700°C.This phase transformation explains the reason that the oxygen permeation flux of BaFe0.975Pr0.025O3−δshows a sharp increase near 700°C.

FIG.5 Oxygen permeation fluxes of BaFe1−yPryO3−δmembranes.

FIG.6 HT-XRD patterns of BaFe0.975Pr0.025O3−δ membrane.

IV.CONCLUSION

BaFe1−yPryO3−δ(y=0,0.025,0.05,0.075,0.1)powders were synthesized by a solid state reaction method.The BaFeO3−δand BaFe0.975Pr0.025O3−δsamples have hexagonal and triclinic crystal structure at room temperature,respectively,while others have cubic crystal structure,which proves that doping of praseodymium is beneficial to the stabilization of the cubic phase structure.The sintered BaFe1−yPryO3−δsamples have dense microstructure and praseodymium doping promotes the grain growth.Electrical conductivity and oxygen permeation flux of BaFe1−yPryO3−δsamples increase with the increase of the praseodymium doping amount,which reach 6.5 S/cm and 1.112 mL/(cm2·min)for BaFe0.9Pr0.1O3−δcomposition at 900°C,respec-tively.The test results of high temperature XRD show that the crystal structure of BaFe0.975Pr0.025O3−δgradually transforms from triclinic to cubic at temperature around 700°C,which results in a sharp increase in oxygen permeation flux of the materials near around this temperature.

V.ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China(No.216060647)and the Industry-University-Research Project of Aviation Industry Corporation of China(No.cxy2012HFGD025).

[1]A.R.Smith and L.Klosek,Fuel Process Technol.70,115(2001).

[2]K.S.Knaebel and F.B.Hill,Chem.Eng.Sci.40,2351(1985).

[3]S.P.S.Badwal and F.T.Ciacchi,Adv.Mater.13,993(2001).

[4]J.Sunarso,S.Baumann,J.M.Serra,W.A.Meulenberg,S.Liu,Y.S.Lin,and J.C.Diniz da Costa,J.Membrane Sci.320,13(2008).

[5]J.W.Zhu,G.P.Liu,Z.K.Liu,Z.Y.Chu,W.Q.Jin,and N.P.Xu,Adv.Mater.28,3511(2016).

[6]W.Ito,T.Nagai,and T.Sakon,Solid State Ionics178,809(2007).

[7]Z.H.Chen,R.Ran,Z.P.Shao,H.Yu,J.C.D.da Costa,and S.M.Liu,Ceram.Int.35,2455(2009).

[8]Y.Teraoka,H.M.Zhang,S.Furukawa,and N.Yamazoe,Chem.Lett.14,1743(1985).

[9]H.Kruidhof,H.J.M.Bouwmeester,R.H.E.V.Doorn,and A.J.Burggraaf,Solid State Ionics63−65,816(1993).

[10]L.Qiu,T.H.Lee,L.M.Liu,Y.L.Yang,and A.J.Jacobson,Solid State Ionics76,321(1995).

[11]H.Q.Xie,Y.Y.Wei,and H.H.Wang,Chin.J.Chem.Eng.25,892(2017).

[12]M.B.Choi,D.K.Lim,S.Y.Jeon,H.S.Kim,and S.J.Song,Ceram.Int.38,1867(2012).

[13]T.Nagai,W.Ito,and T.Sakon,Solid State Ionics177,3433(2007).

[14]G.R.Zhang,Z.K.Liu,N.Zhu,W.Jiang,X.L.Dong,and W.Q.Jin,J.Membrane Sci.405/406,300(2012).

[15]Y.F.Cheng,H.L.Zhao,D.Q.Teng,F.S.Li,X.G.Lu,and W.Z.Ding,J.Membrane Sci.322,484(2008).

[16]Q.Yuan,Q.Zhen,R.Li,and W.Tan,J.Funct.Mater.45,7051(2014).

[17]J.Xue,Q.Liao,Y.Y.Wei,Z.Li,and H.H.Wang,J.Membrane Sci.443,124(2013).

[18]K.E fimov,T.Halfer,A.Kuhn,P.Heitjans,J.Caro,and A.Feldhoff,Chem.Mater.22,1540(2010).

[19]H.Wang,C.Tablet,A.Feldhoff,and J.Caro,Adv.Mater.17,1785(2005).

[20]X.F.Zhu,H.H.Wang,and W.S.Yang,Chem.Commun.1130(2004).

[21]K.Watanabe,D.Takauchi,M.Yuasa,T.Kida,K.Shimanoe,Y.Yasutake,and N.Yamazoe,J.Electrochem.Soc.156,E81(2009).

[22]M.A.Peña and J.L.G.Fierro,Chem.Rev.101,1981(2001).

[23]N.Ramadass,Mater.Sci.Eng.36,231(1978).

[24]A.F.Sammells,R.L.Cook,J.H.White,J.J.Osborne,and R.C.Macduff,Solid State Ionics52,111(1992).

[25]K.Watenabe,M.Yuasa,T.Kida,Y.Teraoka,N.Yamazoe,and K.Shimanoe,Adv.Mater.22,2367(2010).

[26]Y.J.Wang,Q.Liao,L.Y.Zhou,and H.H.Wang,J.Membrane Sci.457,82(2014).

[27]Q.Liao,Y.J.Wang,Y.Chen,and H.H.Wang,Chin.J.Chem.Eng.24,339(2016).

[28]D.Xu,F.F.Dong,Y.B.Chen,B.T.Zhao,S.M.Liu,M.O.Tade,and Z.P.Shao,J.Membrane Sci.455,75(2014).

[29]T.Kida,A.Yamasaki,K.Watanabe,N.Yamazoe,and K.Shimanoe,J.Solid State Chem.183,2426(2010).

[30]S.S.Li,J.G.Cheng,Y.Gan,P.P.Li,X.C.Zhang,and Y.Wang,Sur.Coat.Technol.276,47(2015).

[31]T.Kida,D.Takachi,K.Watanabe,M.Yuasa,K.Shimanoe,Y.Teraoka,and N.Yamazoe,J.Electrochem.Soc.156,E187(2009).

[32]Salehi.M,F.Clemens,E.M.Pfaff,S.Diethelm,C.Leach,and T.Graule,J.Membrane Sci.382,186(2011).

[33]W.D.Penwell and J.B.Giorgi,Sens.Actuators B Chem.191,171(2014).

CHINESE JOURNAL OF CHEMICAL PHYSICS2018年2期

CHINESE JOURNAL OF CHEMICAL PHYSICS2018年2期

- CHINESE JOURNAL OF CHEMICAL PHYSICS的其它文章

- Investigation on Preparation and Anti-icing Performance of Superhydrophobic Surface on Aluminum Conductor

- Study of Cadmium-Doped Zinc Oxide Nanocrystals with Composition and Size Dependent Band Gaps

- Glucose Isomerization into Fructose Catalyzed by MgO/NaY Catalyst

- Analysis of Solvent Effect on Mechanical Properties of Poly(ether ether ketone)Using Nano-indentation

- Direct Synthesis of Monodisperse Hollow Molecularly Imprinted Polymers Based on Unfunctionalized SiO2for the Recognition of Bisphenol A

- Agent-Based Network Modeling Study of Immune Responses in Progression of Ulcerative Colitis