What do coaches want to know about sports-related concussion?A needs assessment study

Lindsay Sullivan*,Michal Molcho

aSchool of Health Sciences,Discipline of Health Promotion,NUI Galway,Galway,Ireland

bSchool of Arts,Social Sciences,and Celtic Studies,Children’s Studies Programme,NUI Galway,Galway,Ireland

1.Introduction

Sports-related concussion(SRC)has been identified as a public health priority,with an estimated 1.6 to 3.8 million sports and recreation-related concussions sustained each year in the USA alone.1A high proportion of these concussions are sustained by young athletes under 18 years of age,which potentially represents a gross underestimate of the prevalence of this injury,as the diagnosis of concussion relies primarily on the self-reporting of symptoms and the recognition of concussion signs and symptoms by supervising adults.2Concussion is a mild traumatic brain injury,defined as a complex pathophysiological process affecting the brain induced by biomechanical forces.3Concussion-causing collisions can be subtle,and signs and symptoms of concussion(such as headache,nausea,and dizziness)are often non-specific and resolve spontaneously.4,5Evidence of the potentially harmful cumulative effects from SRC,which include long-term changes in brain function,6-12has been demonstrated in individuals who have sustained multiple concussions and among retired professional Americantype football and rugby athletes.13-15Young athletes have been found to be more susceptible to SRC than older athletes and to be at increased risk of acute and long-term complications post-concussion.16-22

In Ireland,Gaelic football and hurling(the name camogie is used when there are exclusively female athletes)are the national sports.Both Gaelic football and hurling are amateur sports,governed by the Gaelic Athletic Association(GAA).These sports are played by more than 100,000 athletes,in 2500 sports clubs throughout the isle of Ireland,but are also played globally,with increasing participation in recent years.23

Both Gaelic football and hurling are characterized by highvelocity,multi-directional,and high physical contact elements,as well as the high speed at which they are played.24-26These characteristics,when coupled with high physical contact,acceleration,deceleration and turning,leaves GAA athletes at considerable risk for injury,24,27,28including SRC.29More specifically,previous research has found that approximately 25%of GAA athletes reported having played in practice or during a match while symptomatic from concussion.29Research amongst this population also found that GAA athletes lack a complete understanding of concussion,as common misconceptions prevailed,suggesting that a concussion education program amongst this population of athletes may be warranted.29

Similar to many youth sporting events worldwide,medical professionals are rarely present during GAA practices or games at the grassroots level.Therefore,coaches play a crucial role in recognizing the signs and symptoms of concussion and ensuring that players with a suspected concussion are managed correctly.30-32Despite their identified role in the detection and management of concussion,research has found that coaches lack knowledge about the signs and symptoms of concussion,the short-and long-term health consequences associated with this injury,and the most up-to-date concussion management guidelines.33,34This finding causes concern as inappropriate management and non-disclosure of concussion may increase an athlete’s risk of more severe health consequences,including further brain injury or possibly death,caused by second impact syndrome.35,36As such,it is imperative that coaches become well educated in the identification and management of concussion and the appropriate and effective communication of the importance of concussion reporting and safety to their athletes.

Despite an increasing body of research and public awareness about concussive injury and recovery,relatively little is known about the most effective way(s) to disseminate this information to coaches,players,parents,and clinicians.37-40Education efforts to reduce the prevalent risk behaviors of continued play while symptomatic have been largely ineffective.37,39-41Specifically,the majority of evaluations have reported short-term benefits after being exposed to a concussion education program, while findings regarding the long-term benefits,such as improvements in participants’knowledge,behaviors,management practices,and attitudes toward concussions,were less clear and inconsistent.37,39-44For example,the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s“Heads Up”concussion education program provides free information for coaches,parents,and physicians in a variety of formats,which include online training,fact sheets,and posters.This program,which is widely distributed to youth and high school coaches across the USA,has been found to increase coaches’knowledge and awareness of the severity of concussion and has resulted in increased efforts to minimize the risks of concussion.43However,anecdotal evidence has also suggested that these materials are not widely utilized by coaches and may not be effective in changing coaches’concussion management practices;which suggests that passive education materials may not be widely adopted by coaches or the most effective mode of delivery of concussion education.31Additional evidence suggests that many coaches face barriers to preventing and addressing concussions amongst their teams,due to a lack of concussion specific injury policies and the tendency of athletes and their parents to discount the potential severity of this injury.43

As such,it is imperative that concussion education strategies are adapted to the specific audience,that barriers and facilitators of knowledge use are assessed,and that a proper intervention strategy is chosen,implemented,and evaluated.Therefore,assessing coaches’needs and priorities is an important first step in improving concussion education and prevention programs provided to this population,at present.Despite this,to our knowledge,this is the first piece of research that has explored coaches’educational needs and preferences for a concussion education program,as well as their compliance with best-practice return to-play(RTP)guidelines and management practices.

The primary aim of this study was to assess the SRC informational needs and desires of a sample of coaches in terms of both content and preferred method of delivery.This study also set out to assess and describe current practices and policies in relation to SRC education,management,and RTP guidelines among GAA clubs throughout Ireland and to explore whether clubs and coaches are in compliance with the SRC management and RTP guidelines adopted by the sport’s governing body,the GAA.

2.Methods

2.1.Sample and procedure

One hundred and eight coaches(out of 135 coaches)from all 4 provinces of the isle of Ireland(Connacht,Leinster,Munster,and Ulster)completed the survey(completion rate=80.0%).Participants who coached(1)Gaelic football,(2)Ladies’football,(3)hurling,and(4)camogie were included in the sample.County-level Games Development Officers received an initial contact email from the GAA,Ladies Gaelic Football Association,or Camogie Association.The email contained a description of the study,an information sheet,and a link to the online survey.They were asked to circulate or forward this email to all coaching staff and GAA clubs within their respective county.The survey was confidential and anonymous.The online survey was completed electronically during June 3rd-September 29th,2015.Participants were first provided with information about the study to review prior to participation,with an additional statement stating that by continuing the survey,they agree to participate in the study.By completing and submitting the online survey,participants provided implied consent.All study procedures were approved by the NUI Galway Research Ethics Committee.

2.2.Measures

Participants were asked about the following:(1)demographic characteristics,(2)self-reported informational needs and desires,(3)preferred methods of delivery,and(4)concussion practices and procedures.A pilot study was conducted to assess item construction,comprehension,ease of completion,and internal validity using a small sample of coaches from the target population.Feedback was incorporated to produce the final version of the instrument.

2.2.1.Self-reported informational needs and desires

To determine if concussion training could benefit this population,coaches were asked“In the last season,how many concussions did players on your team sustain?”Participants were also asked to indicate on a 5-item Likert scale(1=not at all interestedto 5=very interested)how interested they would be in receiving various information about concussion(i.e.,symptoms and signs of concussion,health consequences,RTP guidelines).Subsequently,participants were asked to list 3 topics that they would like included most in a concussion education program.Written responses were collated,and specific themes were identified.

2.2.2.Methods of delivery

Participants were asked to select from a list“What method of training do you feel would be most effective in terms of concussion education?”Participants were then asked to rate how effective they believed various methods of training(i.e.,training seminar or workshop,video,online module)would be for concussion education(1=not very effective,2=somewhat effective,3=very effective).In addition,participants were asked to indicate how they would prefer to get information on SRC.

2.2.3.Practices and procedures

2.2.3.1.Utilizationofconcussioneducationmaterials.To examine whether the SRC educational materials provided by the GAA were being utilized by coaches,participants were provided with a list of all the SRC materials available on the GAA website and asked to report“yes”or“no”as to whether or not they have accessed each resource.The number of resources accessed by coaches was then computed,with higher scores reflecting a greater number of resources accessed(range:0 to 7).

2.2.3.2.Concussion training and management within clubs.Respondents were asked about the concussion training and management practices within their clubs.Participants were asked whether or not their club provides concussion education for coaches,players,or parents,with response options of“yes”,“no”,or“I don’t know”.Participants were asked 3 additional questions regarding their clubs’concussion management practices.Specifically,coaches were asked when an athlete has a concussion,does their club(1)follow the GAA’s RTP protocol,(2)provide a written plan for concussion management,and(3)report to a parent or guardian(for players under 18 years old).Response options for these aforementioned questions included“yes”,“no”,and “I don’t know”.Communication about concussion and concussion safety practices were determined by asking participants“Before the season starts,I talk to my players about the importance of managing concussions properly.”

2.3.Statistical analyses

Data analyses were conducted using SPSS software,Version 22.0(IBM Corp.,Armonk,NY,USA).Data were analyzed using descriptive and inferential statistics.Frequencies were also computed for all demographic variables.Open-ended questions were collated,and specific themes were identified using thematic analysis.Pearson χ2tests were used to examine differences in communication practices about concussion and concussion safety by participant’s demographic characteristics(i.e.,formal concussion education,gender,sport(s)coached).An α level ofp< 0.05 was adopteda priorias the threshold for significance in all analyses.

3.Results

3.1.Demographic variables

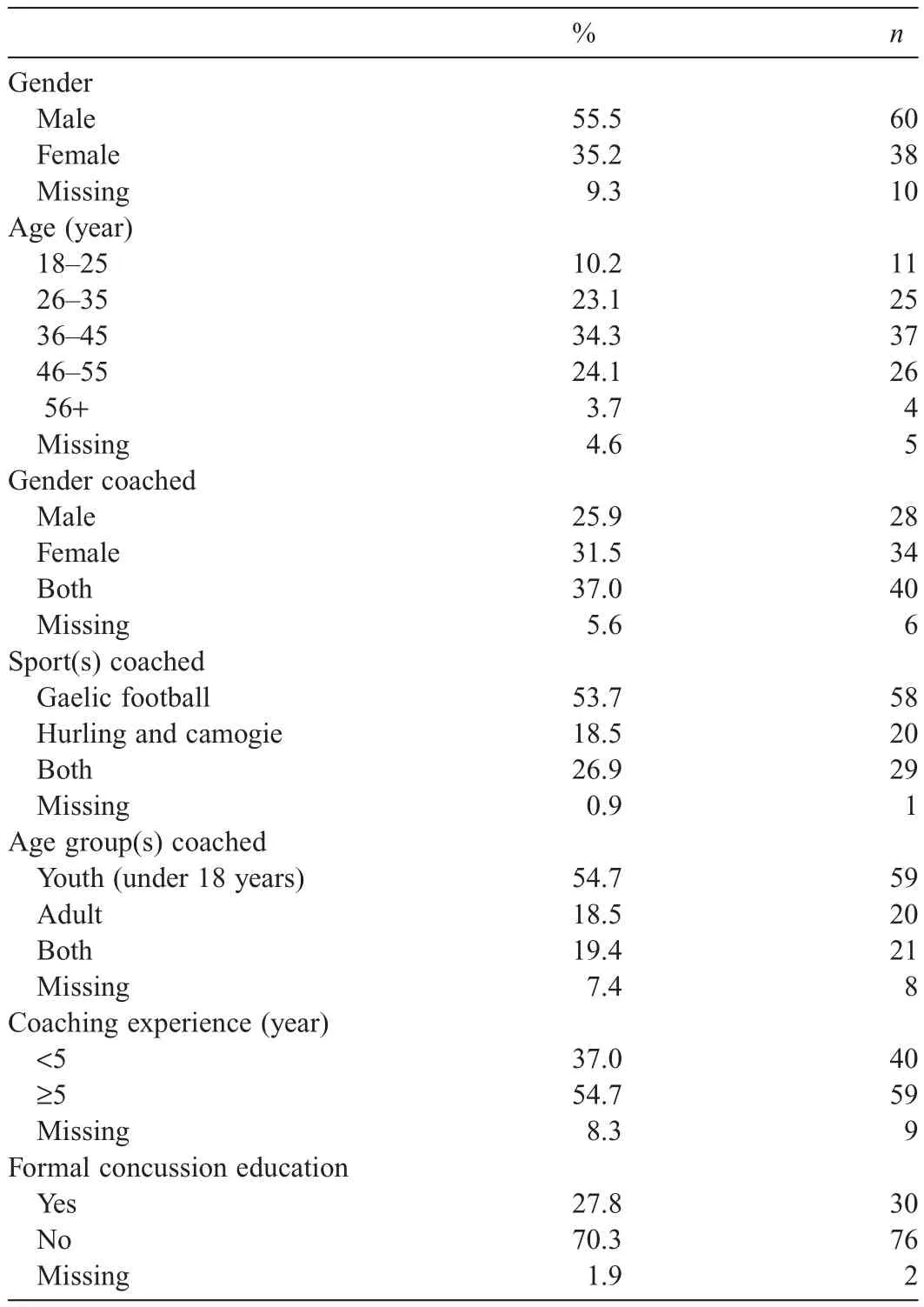

Table 1 summarizes the demographic characteristics of the study sample.The sample was predominately male(55.5%),coaching young athletes(54.7%),and Gaelic football(53.7%).A majority of the coaches had 5 or more years of coaching experience(54.7%),and approximately a quarter of the participants have been formally educated about SRC.

3.2.Self-reported informational needs and desires

Overall,coaches reported that in the previous season,on average,1.07±0.97(range 0-4)concussions were diagnosed amongst their team members.This suggests that concussionsare common enough in GAA athletes,thus suggesting concussion training could be of benefit for GAA coaches.We therefore examined what are the training needs that were identified by GAA coaches.

Table 1Demographic characteristics of the sample(n=108).

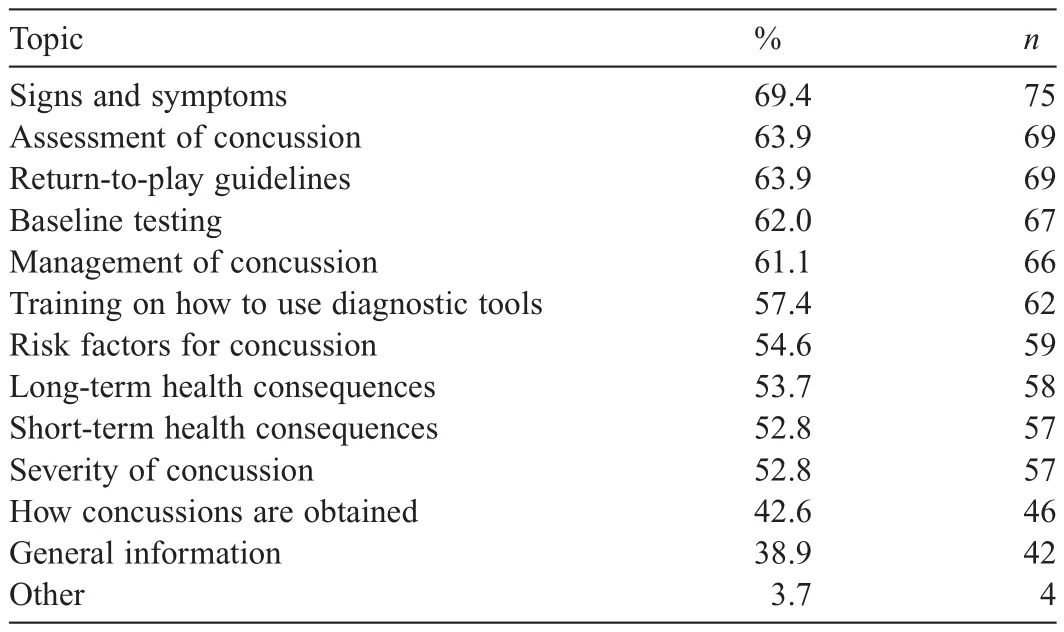

Table 2Topics and the proportion of respondents scoring “very interested”(n=108).

The top 3 topics that coaches indicated that they would be“very interested”in receiving information about(1)the signs and symptoms of concussion(69.4%),(2)assessment of concussion(63.9%),and(3)RTP guidelines(63.9%).Table 2 provides a breakdown of topics and the proportion of respondents scoring“very interested”in receiving information about that topic.

Participants were also asked to provide written suggestions on the 3 topics that they would most want included in a concussion education program.The written suggestions were collated,and specific themes and topics were identified.The 3 most commonly reported topics were(1)management of concussion(41.7%),(2)the signs and symptoms of concussion(22.9%),and(3)RTP guidelines(17.7%).Such topics align with the topics respondents indicated that they would be“very interested”in receiving information about,outlined above.Other popular topics that emerged include the dangers and health consequences of concussion(11.5%)and concussion assessment(7.3%).

3.3.Methods of delivery

Participants were asked about their preferred methods of SRC education delivery.Approximately two-thirds of participants indicated that in-person training would be the most effective method of concussion education training,followed by an online module(14.8%)and an educational video(7.4%).Coaches indicated that workshops or seminars would be the most commonly utilized method of SRC education.Approximately one-in-two participants reported they would seek information about concussion online through an informational website,and a third of participants reported that they would seek information about SRC via a video or informational sheets.

3.4.Practices and procedures

3.4.1.Utilization of concussion education materials

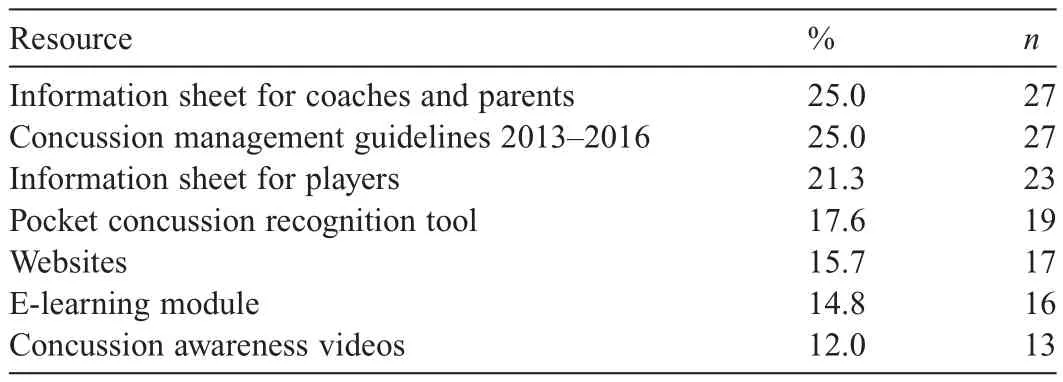

Analysis of self-reported utilization of SRC materials among respondents revealed that 42.6%of coaches indicated that theyhave accessed at least one of the materials on SRC provided by the sport’s governing body,the GAA.The list of resources accessed is presented in Table 3.

Table 3Resource provided and%accessed by coaches(n=108).

3.4.2.Concussion training and management within clubs

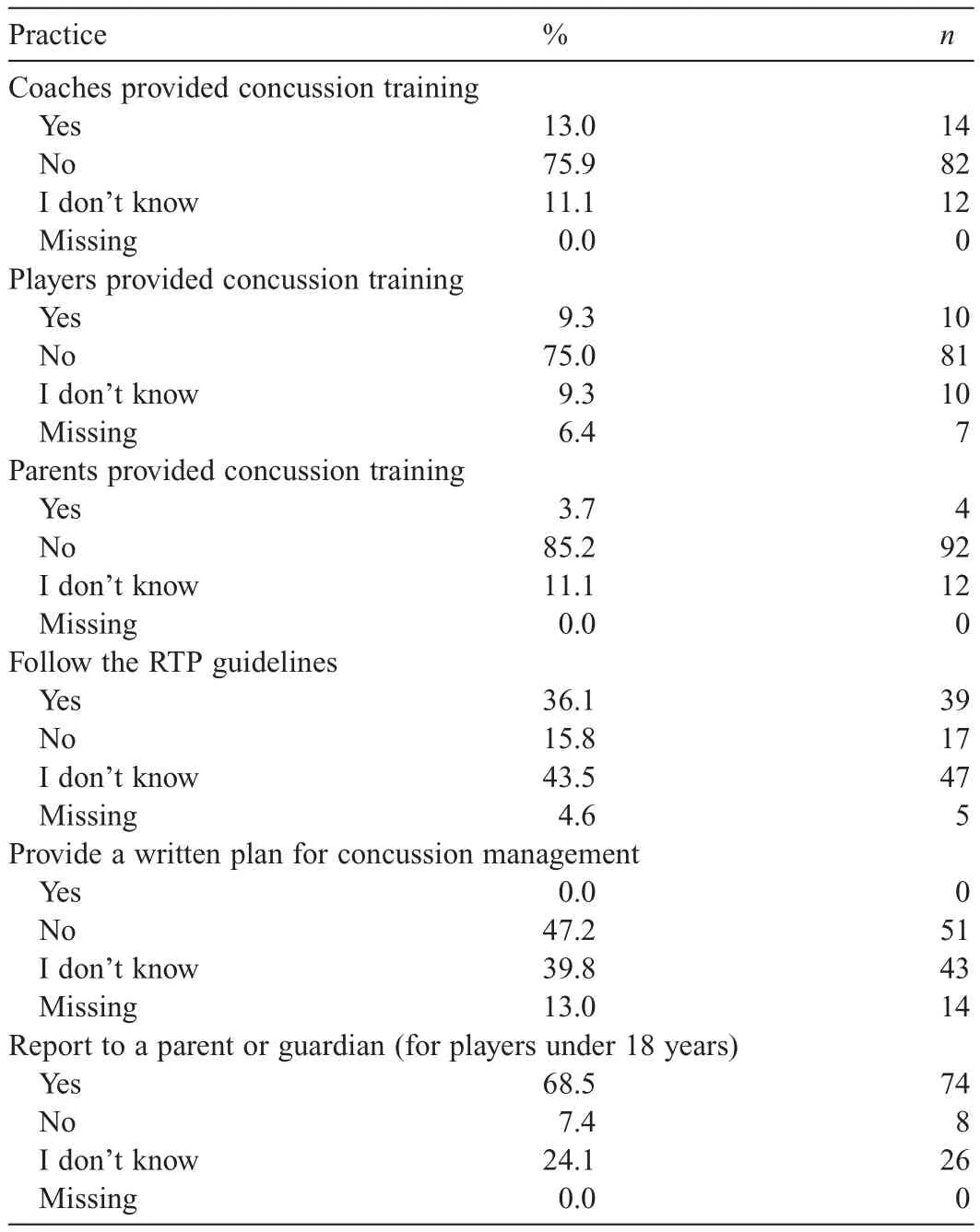

An overwhelming majority of participants reported that their club does not provide concussion education for coaches(75.9%),players(75.0%),and parents(85.2%).Only one-third of participants indicated that their club follows the RTP guidelines adopted by the GAA,while 15.8%of participants indicated that their club does not follow these guidelines.About half of the participants were not provided a written plan for concussion management and 68.5%indicated that their club reports concussions among under-aged athletes to their parents or guardians(Table 4).

Table 4Concussion training and management practices within clubs(n=108).

3.4.3.Communication about concussion and concussion safety

About 10%of coaches reported that they talked to their players about the importance of concussion management and safety prior to the start of the season.Results indicate that coaches who self-reported that they had been formally educated about concussion were significantly more likely than those who had not been formally educated about SRC to talk to their athletes about concussion management and concussion safety,χ2(1,n=101)=5.84,p<0.05.There were no significant differences in communication practices and participants’age,gender,gender coached,sport(s)coached,and age group coached.

4.Discussion

Concussion,especially in young people,has been recognized as an area of concern.With concussion diagnosis being based primarily on honest self-reporting and the recognition of symptoms by supervising adults,the role of coaches in creating a culture that promotes the self-reporting of this injury and recognizing concussive symptoms among their athletes is important.This paper investigated the current SRC education that is available for GAA coaches,their unmet education needs,and the preferred methods of delivery.

Our study confirms that concussions are a common enough injury amongst GAA athletes and thus warrants concussion training for coaches of all age and skill levels.Yet,despite the selfreported prevalence of concussion among GAA athletes,29and the possible acute and long-term complications associated with this injury,6-15our study found that only one-in-four participants reported being formally educated about SRC.Recently,the GAA has begun to provide concussion education training and materials to knowledge users(i.e.,coaches,parents,and players)in a variety of modalities that include management guidelines,information sheets,and video.Despite this,we found that a majority of coaches reported that their sports club does not provide concussion education to knowledge users nor do they follow the RTP protocol adopted by the GAA.

In addition,our study found that coaches are infrequently accessing the informational resources on SRC available to them.Specifically,we found that 42.6%of coaches have accessed one or more of the materials on SRC provided by the GAA.The most widely utilized resources were the information sheets and concussion management guidelines,both of which were reportedly accessed by 25%of participants,whereas other resources(e.g.,videos,e-learning module,websites)were rarely accessed by participants.These findings suggest that despite a concerted effort from the GAA to raise awareness about SRC and enforce best-practice RTP guidelines,the informational resources provided are not being accessed frequently.Hence,it is important to explore coaches’preferred content and method of delivery for concussion education and to investigate whether these needs align with what information or training is available to them.

Findings demonstrated that an overwhelming majority of participants indicated that in-person training would be the most effective method of concussion education.One-in-two participants indicated that they would seek information about SRC through an informational website,and a third of participants reported that they would seek information via a video or information sheets.Therefore,similar to previous research, we found a disconnect between the concussion education coaches indicate that theywant and the concussion education they are provided,in terms of content and delivery modality.44Taken together,these findings highlight the importance of assessing knowledge users feel they need and embedding these identified needs and learning preferences into the development of concussion education programs.44Embedding the knowledge users’needs and learning preferences into program development may make these programs more efficacious and may ensure that concussion education does in fact change cognitions other than knowledge alone.44

We also found that,before the start of the season,only 10%of coaches talk to their athletes about concussion and concussion safety.This finding is concerning as coaches play a central role in promoting a culture of safety and establishing an environment that values concussion reporting,and ultimately influence whether or not such programs are delivered to players in the first place.44-49Additionally,this finding is of concern as research has found that if a coach communicates their support for concussion reporting to their athletes,their athletes are more likely to report concussion,which in turn results in significantly fewer undiagnosed concussions and fewer athletes returning to play while symptomatic from concussion.47-50

Importantly,results found that coaches who were formally educated about concussion were significantly more likely to talk to their athletes about concussion safety than those who have not been formally educated about concussion.This finding underscores the potential benefits of concussion education programs,which includes the secondary prevention of SRC,and suggests that concussion education programs should highlight the importance of communication about concussion and concussion safety.As such,these findings suggest that interventions should be developed that provide coaches with skills and techniques on how to effectively talk to their team about SRC and how they can reinforce an environment that promotes the reporting of injuries,including concussion.Future research should explore determinants of coach communication about concussion safety48and qualitatively explore the self-perceived barriers and challenges to communication about SRC.

This study has several limitations.It used self-reported data;thus,there is no way to ascertain the accuracy of the information provided by participants.The present study was further limited by the features of the participants.The sample was relatively small and unbalanced by gender and sport(s)coached,with both female coaches and hurling and camogie coaches being under-represented;thus,results may not be generalizable to the GAA population or to other groups of coaches.Data were collected using an online survey methodology,thus,presenting another limitation;as some people still do not have access to email or the Internet,the use of this survey methodology may have resulted in a sample of respondents that are not representative of the population in question.Additionally,because participants volunteered to participate in this survey,our sample may have been influenced by participant’s level of concussion awareness,how serious they believe concussions are,or personal experience(s)with concussion,which may have resulted in bias.It is therefore possible that the study provides an overestimation of knowledge about and awareness of SRC.Further research is needed to extend the generalizability of these findings to a larger sample.Additional research should also characterize the concussion education provided to and investigate the felt needs of coaches of other contact and collision sports and geographic locations.44Despite these limitations,this study provides a strong initial foundation from which a theory-based concussion education program,tailored to the target audience and context,can be developed.

5.Conclusion

This paper describes the current concussion education and communication practices of a subset of coaches in Ireland,as well as their learning preferences.Our findings suggest that there is a disconnect between the concussion education provided to coaches and their learning preferences.Results also demonstrated that this subset of coaches is not communicating their support for concussion reporting to their teams.These results suggest a need for a multifaceted approach to concussion education,tailored to the individual needs and learning preferences of the target population.To increase the efficacy of concussion education programs,these programs should be rooted in theories of health communication and best practices for program planning,dissemination,and evaluation.44

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by the Irish Research Council(Grant No.GOIPG/2014/914).

Authors’contributions

LS acquired the data for this study;LS and MM contributed to the formulation of the idea,analysis,and interpretation of data,the drafting of the manuscript,and completed revisions of the manuscript.Both authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript,and agree with the order of presentation of the authors.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

1.Wiebe DJ,Comstock RD,Nance ML.Concussion research:a public health priority.Inj Prev2011;17:69-70.

2.McCrory P,Meeuwisse W,Johnston K,Dvorak J,Aubry M,Molloy M,et al.Consensus statement on concussion in sport:the 3rd International Conference on Concussion in Sport held in Zurich,November 2008.JAthl Train2009;44:434-48.

3.McCrory P,Meeuwissse WH,Aubry M,Cantu B,Dvorak J,Echemendia RJ,et al.Consensus statement on concussion in sport:the 4th International Conference on Concussion in Sport held in Zurich,November 2012.JAthl Train2013;48:554-75.

4.Chrisman SP,Quitiquit C,Rivara FP.Qualitative study of barriers to concussive symptom reporting in high school athletics.J Am Coll Surg2013;216:e55-71.

5.Stewart TC,Gilliland J,Fraser DD.An epidemiologic profile of pediatric concussions:identifying urban and rural differences.JTraumaAcute Care Surg2014;76:736-42.

6.Omalu B.Chronic traumatic encephalopathy.ProgNeurol Surg2014;28:38-49.

7.McKee AC,Cantu RC,Nowinski CJ,Hedley-Whyte ET,Gavett BE,Budson AE,et al.Chronic traumatic encephalopathy in athletes:progressive tauopathy after repetitive head injury.J Neuropathol Exp Neurol2009;68:709-35.

8.Stern RA,Riley DO,Daneshvar DH,Nowinski CJ,Cantu RC,McKee AC.Long-term consequences of repetitive brain trauma:chronic traumatic encephalopathy.PM R2011;3(Suppl.2):S460-7.

9.Omalu B,DeKosky ST,Minster RL,Kamboh MI,Hamilton RL,Wecht CH.Chronic traumatic encephalopathy in a National Football League player.Neurosurgery2005;57:128-34.

10.Kontos AP,Covassin T,Elbin RJ,Parker T.Depression and neurocognitive performance after concussion among male and female high school and collegiate athletes.Arch Phys Med Rehabil2012;93:1751-6.

11.Moser RS,Schatz P.Enduring effects of concussion in youth athletes.Arch Clin Neuropsychol2002;17:91-100.

12.Adirim TA.Concussions in sports and recreation.Clin Pediatr Emerg Med2007;8:2-6.

13.Guskiewicz KM,Marshall SW,Bailes J,McCrea M,Cantu RC,Randolph C,et al.Association between recurrent concussion and late-life cognitive impairment in retired professional football players.Neurosurgery2005;57:719-26.

14.Guskiewicz KM,McCrea M,Marshall SW,Cantu RC,Randolph C,Barr W,et al.Cumulative effects associated with recurrent concussion in collegiate football players:the NCAA concussion study.JAMA2003;290:2549-55.

15.Guskiewicz KM,Marshall SW,Bailes J,McCrea M,Harding HP,Matthews A,et al.Recurrent concussion and risk of depression in retired professional football players.Med Sci Sports2007;39:903-9.

16.Halstead ME,Walter KD,Council on Sports Medicine and Fitness.American Academy of Pediatrics.Clinical report sport-related concussion in children and adolescents.Pediatrics2010;126:597-615.

17.Buzzini SR,Guskiewicz KM.Sports-related concussion in the young athlete.Curr Opin Pediatr2006;18:376-82.

18.Moser RS,Schatz P,Jordan BD.Prolonged effects of concussion in high school athletes.Neurosurgery2005;57:300-6.

19.Field M,Collins MW,Lovell MR,Maroon J.Does age play a role in recovery from sports-related concussion?A comparison of high school and collegiate athletes.J Pediatr2003;142:546-53.

20.Karlin AM.Concussion in the pediatric and adolescent population:“different population,different concerns”.PM R2011;3(Suppl.2):S369-79.

21.Collins MW,Lovell MR,Iverson GL,Cantu RC,Maroon JC,Field M.Cumulative effects of concussion in high school athletes.Neurosurgery2002;51:1175-9.

22.Lovell MR,Collins MW,Iverson GL,Field M,Maroon JC,Cantu R,et al.Recovery from mild concussion in high school athletes.J Neurosurg2003;98:296-301.

23.Roe M,Blake C,Gissane C,Collins K.Injury scheme claims in Gaelic games:a review of 2007-2014.J Athl Train2016;51:303-8.

24.Cromwell F,Walsh J,Gormley J.A pilot study examining injuries in elite Gaelic footballers.Br J Sports Med2000;34:104-8.

25.Murphy JC,O’Malley E,Gissane C,Blake C.Incidence of injury in Gaelic football:a 4-year prospective study.Am J Sports Med2012;40:2113-20.

26.Blake C,O’Malley E,Gissane C,Murphy JC.Epidemiology of injuries in hurling:a prospective study 2007-2011.BMJ Open2014;4:e005059.doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2014-005059

27.Reilly T,Doran D.Science and Gaelic football:a review.J Sports Sci2001;19:181-93.

28.Wilson F,Caffrey S,King E,Casey K,Gissane C.A 6-month prospective study of injury in Gaelic football.Br J Sports Med2007;41:317-21.

29.Sullivan L,Thomas AA,Molcho M.An evaluation of Gaelic Athletic Association(GAA)athletes’self-reported practice of playing while concussed,knowledge aboutand attitudes towards sports-related concussion.Int J Adolesc Med Health2016;29:(3).doi:10.1515/ijamh-2015-0084.

30.Guilmette TJ,Malia LA,McQuiggan MD.Concussion understanding and management among New England high school football coaches.Brain Inj2007;21:1039-47.

31.Glang A,Koester MC,Beaver SV,Clay JE,McLaughlin KA.Online training in sports concussion for youth sports coaches.Int J Sports Sci Coach2010;5:1-12.

32.Register-Mihalik JK,Guskiewicz KM,McLeod TC,Linnan LA,Mueller FO,Marshall SW.Knowledge,attitude,and concussion reporting behaviors among high school athletes:a preliminary study.J Athl Train2013;48:645-53.

33.McLeod TC,Schwartz C,Bay RC.Sport-related concussion misunderstandings among youth coaches.Clin J Sport Med2007;17:140-2.

34.White PE,Newton JD,Makdissi M,Sullivan SJ,Davis G,McCrory P,et al.Knowledge about sports-related concussion:is the message getting through to coaches and trainers?Br J Sports Med2014;48:119-24.

35.Cantu RC.Second-impact syndrome.Clin Sports Med1998;17:45-60.

36.McCrory PR,Berkovic SF.Second impact syndrome.Neurology1998;50:677-83.

37.Caron JG,Bloom GA,Falcão WR,Sweet SN.An examination of concussion education programmes:a scoping review methodology.Inj Prev2015;21:301-8.

38.Provvidenza CF,Johnston KM.Knowledge transfer principles as applied to sport concussion education.Br J Sports Med2009;43(Suppl.1):S68-75.

39.Kroshus E,Baugh CM,Daneshvar DH.Content,delivery,and effectiveness of concussion education for US college coaches.Clin J Sports Med2016;26:391-7.

40.Kroshus E,Daneshvar DH,Baugh CM,Nowinski CJ,Cantu RC.NCAA concussion education in ice hockey:an ineffective mandate.Br J Sports Med2014;48:135-40.

41.Kroshus E,Baugh CM,Hawrilenko M,Daneshvar DH.Pilot randomized evaluation of publically available concussion education materials:evidence of a possible negative effect.Health Educ Behav2015;42:153-62.

42.Bagley AF,Daneshvar DH,Schanker BD,Zurakowski D,d’Hemecourt CA,Nowinski CJ,et al.Effectiveness of the SLICE program for youth concussion education.Clin J Sport Med2012;22:385-9.

43.Sarmiento K,Mitchko J,Klein C,Wong S.Evaluation of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s concussion initiative for high school coaches: “Heads Up:Concussion in High School Sports”.J Sch Health2010;80:112-8.

44.Kroshus E,Baugh CM.Concussion education in U.S.collegiate sport:what is happening and what do athletes want?Health Educ Behav2016;43:182-90.

45.Newton JD,White PE,Ewing MT,Makdissi M,Davis GA,Donaldson A,et al.Intention to use sport concussion guidelines among community-level coaches and sports trainers.J Sci Med Sport2014;17:469-73.

46.Finch CF,McCrory P,Ewing MT,Sullivan SJ.Concussion guidelines need to move from only expert content to also include implementation and dissemination strategies.Br J Sports Med2012;47:12-4.

47.Baugh CM,Kroshus E,Daneshvar DH,Stern RA.Perceived coach support and concussion symptom-reporting:differences between freshmen and non-freshmen college football players.J Law Med Ethics2014;42:314-22.

48.Kroshus E,Baugh CM,Hawrilenko MJ,Daneshvar DH.Determinants of coach communication about concussion safety in US collegiate sport.Ann Behav Med2015;49:532-41.

49.Kroshus E,Garnett B,Hawrilenko M,Baugh CM,Calzo JP.Concussion under-reporting and pressure from coaches,teammates,fans,and parents.Soc Sci Med2015;134:66-75.

50.Kroshus E,Baugh CM,Daneshvar DH,Viswanath K.Understanding concussion reporting using a model based on the theory of planned behavior.J Adolesc Health2014;54:269-74.

Journal of Sport and Health Science2018年1期

Journal of Sport and Health Science2018年1期

- Journal of Sport and Health Science的其它文章

- Research highlights from the Status report for step it up!The surgeon general’s call to action to promote walking and walkable communities

- Environments favorable to healthy lifestyles:A systematic review of initiatives in Canada

- The built environment correlates of objectively measured physical activity in Norwegian adults:A cross-sectional study

- The association of various social capital indicators and physical activity participation among Turkish adolescents

- Feasibility of using pedometers in a state-based surveillance system:2014 Arizona Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System

- Matched or nonmatched interventions based on the transtheoretical model to promote physical activity.A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials