Environments favorable to healthy lifestyles:A systematic review of initiatives in Canada

Tegwen Gadais*,Maude Boulanger,François Trudeau,Marie-Claude Rivard

aDépartement des sciences de l’activité physique,Université du Québec à Montréal,Montréal,Québec H2X 1Y4,Canada

bDépartement de psychologie,Université du Québec à Trois Rivières,Trois-Rivières,Québec G9A 5H7,Canada

cDépartement des sciences de l’activité physique,Université du Québec à Trois Rivières,Trois-Rivières,Québec G9A 5H7,Canada

1.Introduction

Healthy food choices and regular physical activity are 2 key behaviors that help prevent the premature development of chronic diseases,obesity,and their complications.1Findings in recent years have identifiedenvironments(physical,sociocultural,economic,and political)as an important factor in promoting healthy lifestyles.2,3Studies on healthy lifestyles have also led to numerous initiatives(e.g.,intervention strategies;programs;national campaigns;action plans;policies and government legislation;and financial support from foundations and official organizations)to encourage the adoption of healthy habits.4-6More specifically,the concept ofenvironments favorable to healthy lifestyles(EFHL)has emerged in public health and the related literature during the past 3 decades.7This concept is difficult to implement,however,owing to its vague definition and the multiple forms of action it includes.A healthfriendly environment does not necessarily prevent sedentary lifestyles or poor food choices.7As a result,more studies on EFHL are needed to develop improved initiatives to promote healthy living.

The Ottawa Charter8was a call for action on health promotion.It initiated a five-fold solution to combat sedentary behavior and unhealthy lifestyles by(1)building healthy public policy,(2)strengthening community action,(3)developing personal skills,(4)creating supportive environments,and(5)reorienting health services.The third point was the main focus of this study.A number of initiatives were subsequently developed in Canada through governmental action plans,which lead to the creation of organizations such as Pace Canada,ParticipACTION,Health Nexus,or the Healthy Living Unit of Health Canada.6There have been various types of projects including promotion programs(e.g.,Grand défiPierre Lavoie,World Day for PhysicalActivity)or more complex intervention strategies(e.g.,school or community programs);6,9and although some have been well documented,the influence of environment has received little attention.There are few literature reviews of studies on environmental perspectives10-14despite the many actions implemented in this regard.It appears a clearer portrait of the Canadian literature on EFHL is needed to better understand(1)the EFHL concept in Canada,(2)studies and findings relative to EFHL,and(3)impacts and future research locations.

The literature shows that a number of models have been employed to organize and understand EFHL-related work.They include the ecological model,which classifies applied health promotion initiatives based on 5 core principles of health behavior(individual,microsystem,mecrosystem,exosystem,and macrosystem),15and the built environment model,which organizes environment in terms of 3 dimensions(transport system,patterns of land use,and urban design).2,16,17We decided,however,on a different and promising guide for our investigation:a Canadian model based on the 2006-2012 action plan of the ministère de la Santé et des Services sociaux du Québec(MSSS).Quebec has been proactive in the field of EFHL,and in 2006 the MSSS targeted environmental influences(“For a common vision of favorable environments”)with the goal of involving stakeholders from many sectors of intervention.In its action plan,the MSSS defined EFHL as“all the physical,sociocultural,political,and economic elements that have a positive influence on diet,physical activity,and body image”.7

1.1.Physical dimension and built environment

There is a broad consensus in the literature that the built environment includes all elements of the physical environment produced by human labor.Examples are public spaces,parks,physical structures(e.g.,homes,schools,shops,etc.)and transport infrastructures(e.g.,cycling paths,streets).17,18A number of operational applications are discussed regarding the contributions of different scientific disciplines(e.g.,geography,public health,education,urban planning,and transportation).19

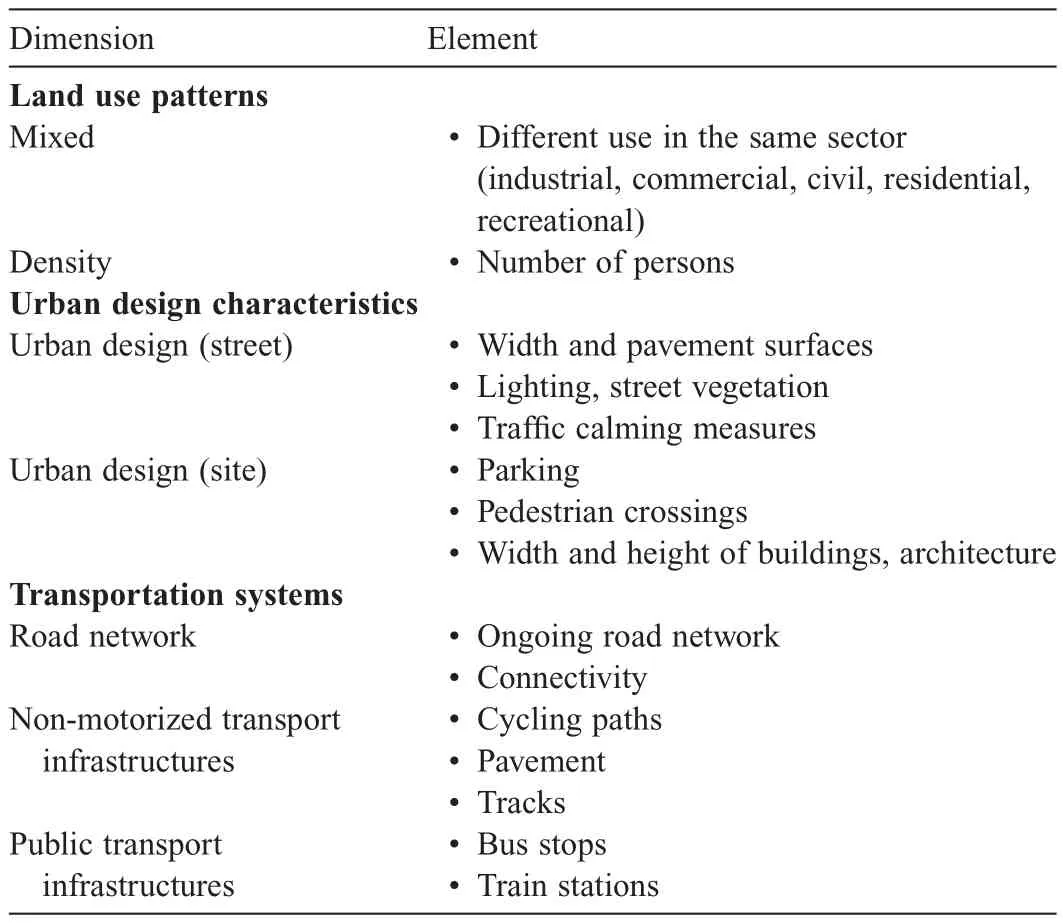

In addition,the physical environment can be divided into 2 categories:natural elements(e.g.,water,river,forest,mountain,or desert)and artificial elements(e.g.,building,road,technology,and urban design),often referred to in the literature as the built environment.Frank et al.16explained that the built environment involves 3 dimensions(land use patterns,urban design characteristics,and transportation systems),which influence the physical activity of the community and can potentially improve its health status(Table 1).In their discussion ofland use patterns,Bergeron et al.5mentioned neighborhood;urban design,proximity and types of restaurants;food options;and sports infrastructures.Urban design characteristicsinfluencepeople’s perception of their environment.For example,a walk in a well-maintained park is more enjoyable than a walk along a traffic-dense road or in an industrial neighborhood.The authors explained that the built environment is a major motivation to become active and adopt healthy lifestyles on an everyday basis.The last dimension,thetransportation systems,includes safe cycling and walking routes,use of stairs instead of elevators,etc.Two studies demonstrate that the better the quality of infrastructure(e.g.,lighting,pavement,security),the greater the probability the community will be active and develop positive perceptions of active transportation.20,21This could lead to less driving and an improvement in air quality.Heath et al.20concluded that the built environment can easily facilitate or restrict physical activity.They strongly recommended involving various authorities such as the health system and the school,community,or municipal governments in the implementation of key modifications to facilitate accessibility and improve environmental safety and aesthetics.Booth et al.3divided environments into 5 levels:international,national or provincial,regional,municipal,and local.Generally speaking,the physical environment appears to be the most thoroughly investigated dimension in the EFHL literature.

Table 1Three dimensions of the built environment.a

1.2.Sociocultural environment

The sociocultural environment is a set of beliefs,customs,practices,and behaviors that exists within a certain population.According to the MSSS,it may be a combination of 3 elements:(1)social connections,(2)norms,and (3)conventions expressed by systems,culture,and traditions.6The sociocultural environment can have a strong impact on nutrition,physical activity,and the motivation to adopt healthy lifestyles.22-24To illustrate,Belon et al.22studied how the community environment shapes physical activity through perceptions revealed through photovoice.Furthermore,family is crucial because it exercises a special influence on young people’s lives with respect to health.Family interaction may lead to a strong sense of family identity and subsequently facilitate or limit the adoption of healthy lifestyles.5

1.3.Political environment

The political sphere relates to all systems involving decision making and involves the examination of political and cultural systems along with elements such as laws,public policies,national or regional action plans,regulatory systems,rules,rights,and relations to authority.7Studies in this area investigate,for example,the tax system as it relates to promoting physical activity,25the Comprehensive School Health approach,26or barriers and supports for healthy eating and physical activity for First Nation youths in northern Canada.27Surprisingly,however,it appears that the political aspect receives little attention whereas it should be essential for supporting EFHL-related actions.

1.4.Economic environment

The final dimension of environment involves structures and production systems.It includes the production,consumption,and use of wealth and resources,all of which can modify economic decisions and priorities.7As an example,changes in food prices can influence the accessibility of food services and products.28,29

To the authors’knowledge,EFHL seems to be ill-defined in Canada,and yet numbers of initiatives have been implemented with this concept in mind.Furthermore,researches on EFHL focus on a variety of themes that include urban design,accident prevention,refugee integration,physical activity promotion,and food distribution.These reasons alone point to the importance of a more thorough investigation of the EFHL concepts and initiatives examined in the Canadian scientific literature.Our aim is twofold: first,to explore the development,objectives,functions,and actions of EFHL in Canada in order to gain an improved understanding of this concept and its applications and second,to guide EFHL stakeholders in their particular fields of action.

The purpose of the present study was to conductan extensive review and analysis of the Canadian scientific research on EFHL published during the past 20 years.Our review was guided by 4 key questions as follows:(1)What research has been published in Canada on EFHL initiatives?(a)When did they start?(b)What is the volume of research?(c)What are their publication metrics?(d)In which refereed journals have they been published?(2)How was the concept of EFHL defined?(a)Which components of EFHL have been studied?(3)What methodologies were used?(a)Which data collection methods were used?(b)Who were the research participants?and(4)What are the findings of these studies?

2.Methods

2.1.Protocol and design

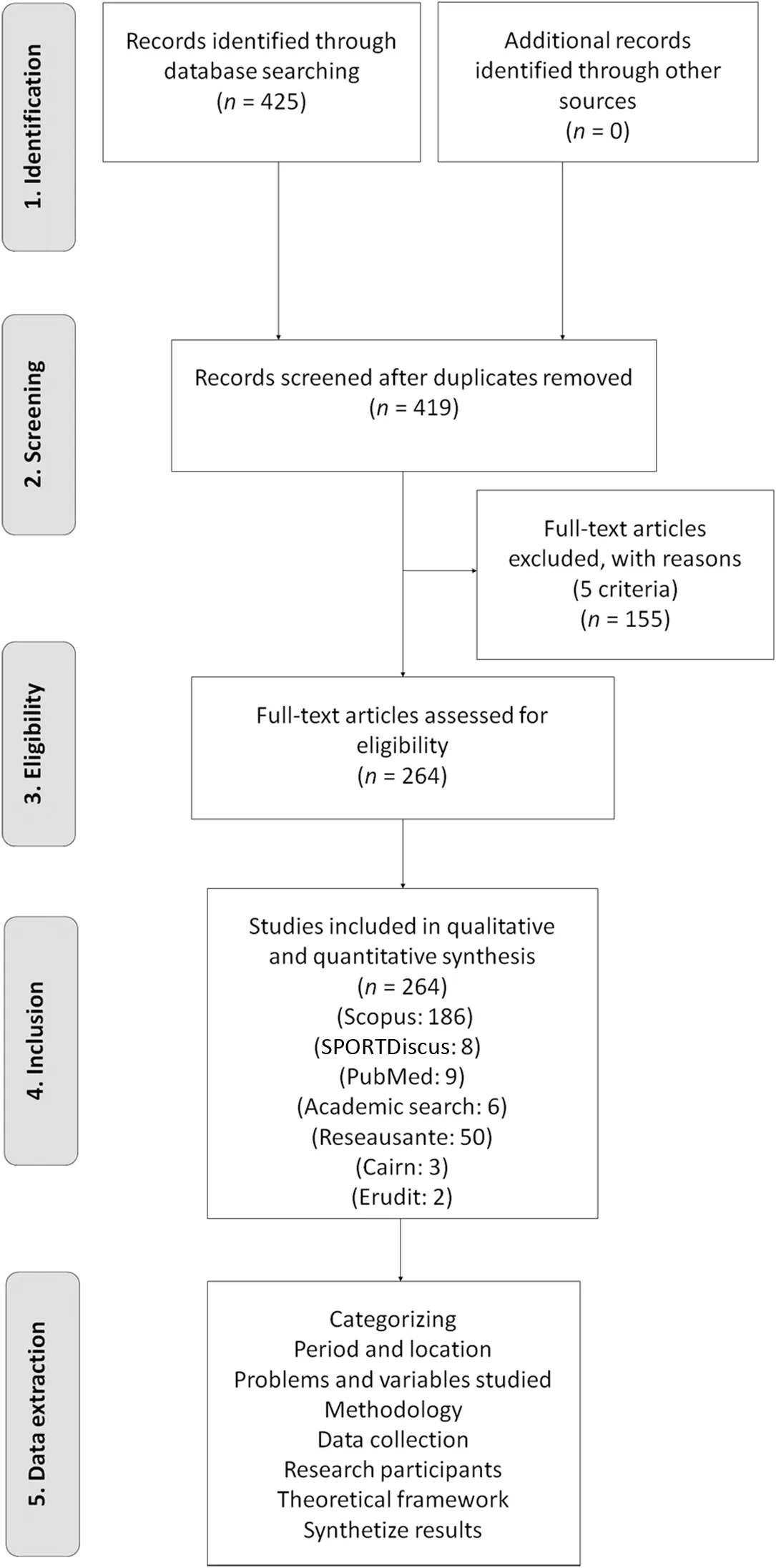

This study used a research design based on the 2 common types of information summaries described by Silverman and Skonie.30They distinguished a published research analysis from a literature review by stating that analyses“are different from literature reviews in that they categorize research instead of synthesizing the results”(p.300).Our objective in exploring the literature was not to systematically review or quantify all evidence,but to create a profile of the multiple potential benefits,as well as the negative effects,of each environmental feature as a tool for policymaking and a guide for future research.The initial intention was to analyze the published research in order to identify and categorize all Canadian scientific literature on EFHL.Because of the substantial number of articles identified,the data extraction was divided into 5 phases of analysis,based on the work of various authors.26,31,32Both the scientific and gray literature were researched.The latter was included because we expected that studies of many subject areas would have been done by government agencies and policy groups rather than scholars.Fig.1 presents the flow chart depicting the 5 steps of the article selection process:identification,screening,eligibility,inclusion,and data extraction.33

2.2.Phase 1:identification of the studies

In the first phase,an exhaustive research through computerized databases was performed to locate all scientific publications on the topic of EFHL.The initial goal was to be inclusive in locating relevant sources of information.Owing to the extent of the overall search and the differences across topics,however,we developed search protocols specific to each topic area and explored specialized search engines in the various fields.Relevant articles were identified by means of a computerized search through multiple bibliographic databases(i.e.,Scopus,SPORTDiscus,PubMed,Academic search complete,Reseausante.com,Cairn,and Erudit)with different combinations of MeSH-terms and keywords(Appendix A).The first author performed the initial selection in the literature search based on the abstract and title(n=425).

2.3.Phase 2:screening

In the second phase,6 duplicates were eliminated and 419 papers were considered.Regarding the scientific literature,we began by looking for systematic and non-systematic reviews and prioritized peer-reviewed articles.The gray literature(Reseausante.com)was also taken into account to ensure no important papers were overlooked.To this end,we targeted reports from credible organizations,that is,groups like government agencies,academic centers,and selected advocacy groups.Newspapers,magazines,and blogs were not searched,except to identify citations from credible reports.The third and fourth authors also identified additional studies on the subject.

2.4.Phase 3:eligibility

The first 2 authors performed a double-blind selection of the abstracts based on inclusion criteria.To remove any doubt,the third and the last authors were consulted.Five inclusion criteria were applied for article eligibility:(a)published between January 1995 and December 2015,(b)conducted in Canada,(c)main subject related to EFHL,(d)available online,and(e)written in French or English.In total,155 full texts were excluded for many reasons(did not meet criteria a,b,c,d,or e)and 264 full papers were included for the qualitative and quantitative synthesis and data extraction.

Fig.1.Flow chart.

2.5.Phase 4:inclusion

This phase corresponds to the validation of the inclusions.A 2×2 table was used to calculate an odds ratio and 95%confidence intervals for dichotomous or categorical measures(131+271)/451 ≈ 0.8914 and Cohen’sdvalue(κ ≈ 0.839)(0.2≤d<0.5:small difference;0.5≤d<0.8:medium difference;d≥0.8:large difference).The fourth phase of the literature search was to obtain copies of the articles identified in the previous phase.Finally,264(62%)publications met our inclusion criteria:(Scopus:186(70.5%);SPORTDiscus:8(3.0%);PubMed:9(3.4%);Academic search complete:6(2.3%);Reseausante.com:50(18.9%);Cairn 3(1.1%);Erudit 2(0.8%))(Appendix B).

2.6.Phase 5:data extraction

A data form was used to extract information concerning the date of study;level of intervention(international,national or provincial,regional,municipal,and local);EFHL dimensions(physical,political,sociocultural,and economic);general methodology(quantitative,qualitative,mixed,situation review,and literature review);data collection(e.g.,survey,document,interview,observation,and focus group);research participants(adults,youth,seniors,and women or girls);theoretical framework used;problem or variables studied;definition of EFHL based on subject studied and results or findings.The first and second authors performed the data extraction and the third and fourth authors verified all extracted data.To remove any doubt,data were discussed until agreement was reached.Once Phase 5 was completed,the analysis and review of the 264 identified articles was begun.The analysis process was structured using the research questions presented in the “Introduction”section above and summarized in the section “Synthesizing the results”below.

2.7.Data analysis

Data analysis was conducted in 2 steps.The first step was to code basic information on the EFHL papers into specific tables for each category.For example,general methodology was coded“QT”if the methods used in the paper were quantitative.We employed the same procedure for levels of intervention,EFHL dimensions,data collection,and research participants.However,the theoretical framework used,problem or variables studied,definition of EFHL based on subject studied and results or findings were coded based on the main idea of the selected text.The second step was to produce descriptive statistics and percentages for each element in the different categories.

2.8.Synthesizing the results

Results are presented in 2 parts.First,we categorize the Canadian articles published.Our aim was to identify and classify the time period of publication,number of publications,refereed journals,research locations,general methodologies,data collection,and characteristics of research participants.Second,we synthesize the results of the published Canadian research.More specifically,we present and summarize the results as follows:(a)EFHL intervention dimensions,(b)EFHL types based on the MSSS7classification,(c)theoretical framework,(d)problems addressed and variables studied,and(e)conceptualization of research subject and findings regarding EFHL topic.

3.Results

3.1.Part 1:categorizing publications

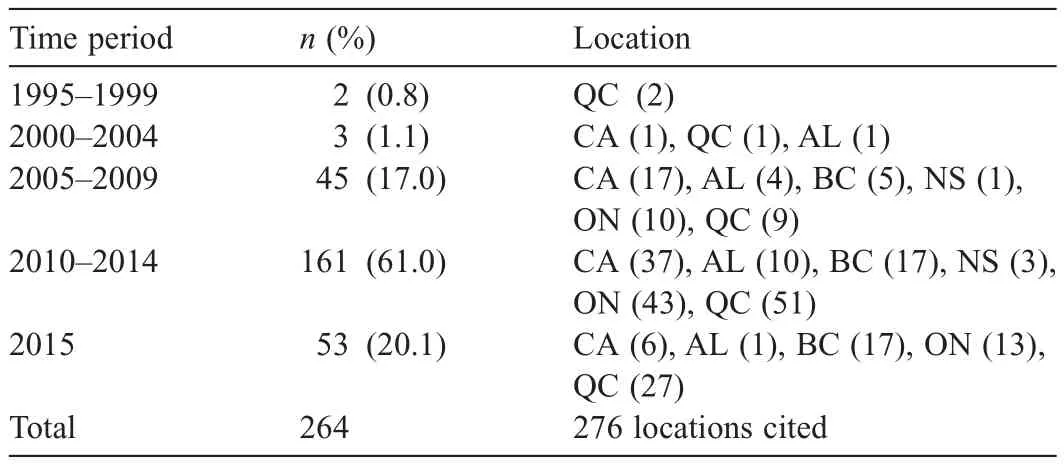

The articles analyzed in this review were published in 88 different refereed journals according to the time period and location(Table 2).Most articles appeared in the following:(a)Canadian Journal of Public Health(n=26),(b)BMC Public Health(n=16),(c)International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity(n=12),(d)Health Places(n=11),and(e)Journal of PhysicalActivity and Health(n=7).We also noted that various subjects were associated with EFHL publications(Accident Analysis and Prevention,Aménagement,Environment and Planning B:Planning and Design,Injury Prevention,Leisure Sciences,Journal of Community Health,Social Market Quarterly,Recherche en soins in firmiers).Most research pertained to 3 Canadian provinces—Quebec,Ontario,and British Columbia—and to Canada as a whole.The number of publications rose sharply during 2010-2014(n=161;61.0%),and the same trend was evident during the following period with 53 publications representing 20.1%of the total only for the year 2015.

Table 2Articles published per period of 5 years and locations of studies.

As Table 3 indicates,4 methodologies were identified:quantitative(n=126),qualitative(n=39),situation review(n=24),and mixed(n=16).Only a few literature reviews were found(n=6).To our knowledge,only 1 study offered a theoretical framework on the topic.34The methodology most widely used in the studies is the quantitative(59.7%)followed by the qualitative(18.5%)and the situation review(11.4%).

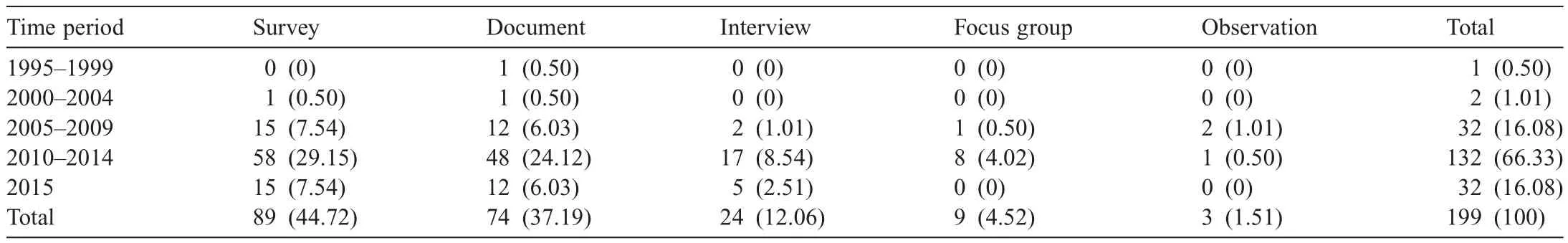

The research articles analyzed used different methods to collect data(Table 4).It should be noted that authors often relied on more than 1 method,while a few neglected to mention it.The most popular data collection methods were surveys(n=89;44.7%)and documents(n=74;37.2%).Examples of the latter include an accelerometer report,a report on number of accidents,or a map of a specific area.Other data collection methods include interviews(n=24;12.1%),focus groups(n=9;4.5%),and observation(n=3;1.5%).Additional methods were used in only a few studies and are not included in Table 4.These have to do with equipment such as an accelerometer(n=8),geographic information system(n=5),pedometer(n=4),or procedures like the motivational journal(n=4),photovoice(n=4),blood samples(n=2),and various measurements of body composition(n=7).

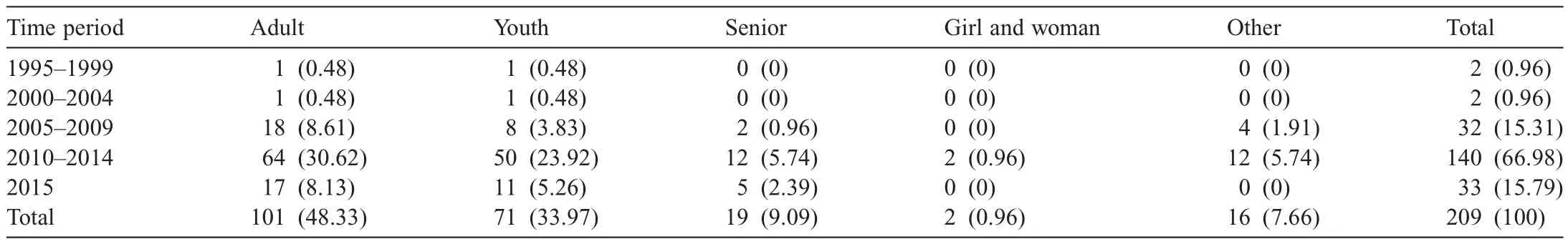

Table 5 lists the categories of participants in the Canadian studies analyzed.Those studied most often for the 5 periods were adults(n=101;48.3%)and young people(n=71;34.0%).Seniors(n=19;9.1%)were most often studied for their walking habits in relation to the environment.35-37Few studies focus on girls or women as regards EFHL(n=2;1.0%).Finally,the “other”category(n=16;7.7%)includes various subjects such as injuries,food products,observations,geographic area,etc.38-40

3.2.Part 2:synthesizing the results of the published research

3.2.1.Intervention levels of EFHL

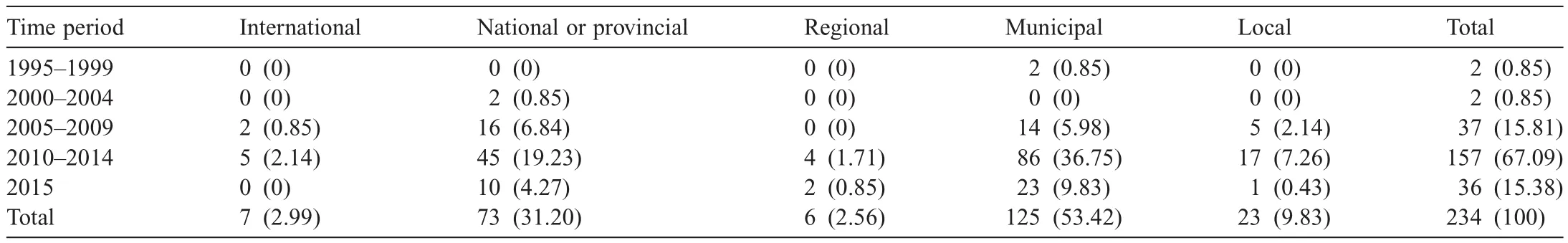

Table 6 shows the intervention levels of the studies analyzed.Most Canadian research initiatives surrounding EFHL wereconducted at the municipal(n=125;53.4%)or national or provincial level(n=73;31.2%).Local(n=23;9.8%),international(n=7;3.0%),and regional(n=6;2.6%)levels were also indicated.

Table 3General methodology(n(%)).

Table 4Data collection methods(n(%)).

Table 5Research participants by time period(n(%)).

3.2.2.EFHL dimensions

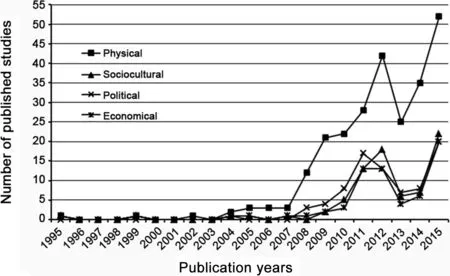

Each study has been classified based on 1 or more of the 4 EFHL dimensions(physical,sociocultural,economic,and political)indicated in Table 7.7Many articles investigated the physical dimension of environment only(n=217;75.1%).The political(n=19;6.6%),sociocultural(n=33;11.4%),and economic(n=20;6.9%)aspects,however,are more often associated with the physical dimension.

3.2.3.Theoretical framework

The EFHL literature published in Canada can be divided into research with or without a theoretical framework.The choice of theoretical framework depends,for the most part,on the EFHL topic covered in the study;as a result,frameworks are very different.Physical activity programs for young people are based on concepts such as SHAPES,41PLAY-ON,42or REAL Kids Alberta.43They can be also inspired by data reports on young people’s physical activity like the Active Healthy Kids Canada Report Card,44Statistics Canada’s Population Estimates and Projections,45or Smart Cities,Healthy Kids.46Thus,youth programs can be structured around data from validated surveys such as Origin-Destination,47Healthy Behavior in School-Aged Children,48,49Space-Time-Activity,50and Statistics Canada’s National Household Survey.51The theoretical frameworks of studies with adults as research participants were also highly diverse:they include surveys such as the National Population Health Survey or the Canadian Community Health Survey from 1996 and 1997 to 2008,52,53theory such as the Diffusion of Innovation Theory,54initiatives such as the Green,Active and Healthy Neighborhoods initiative,55or policies such as public support for active transportation.56The majority of studies analyzed had no theoretical framework;57-63many were situation reviews.13,64,65

3.2.4.Problems and variables studied

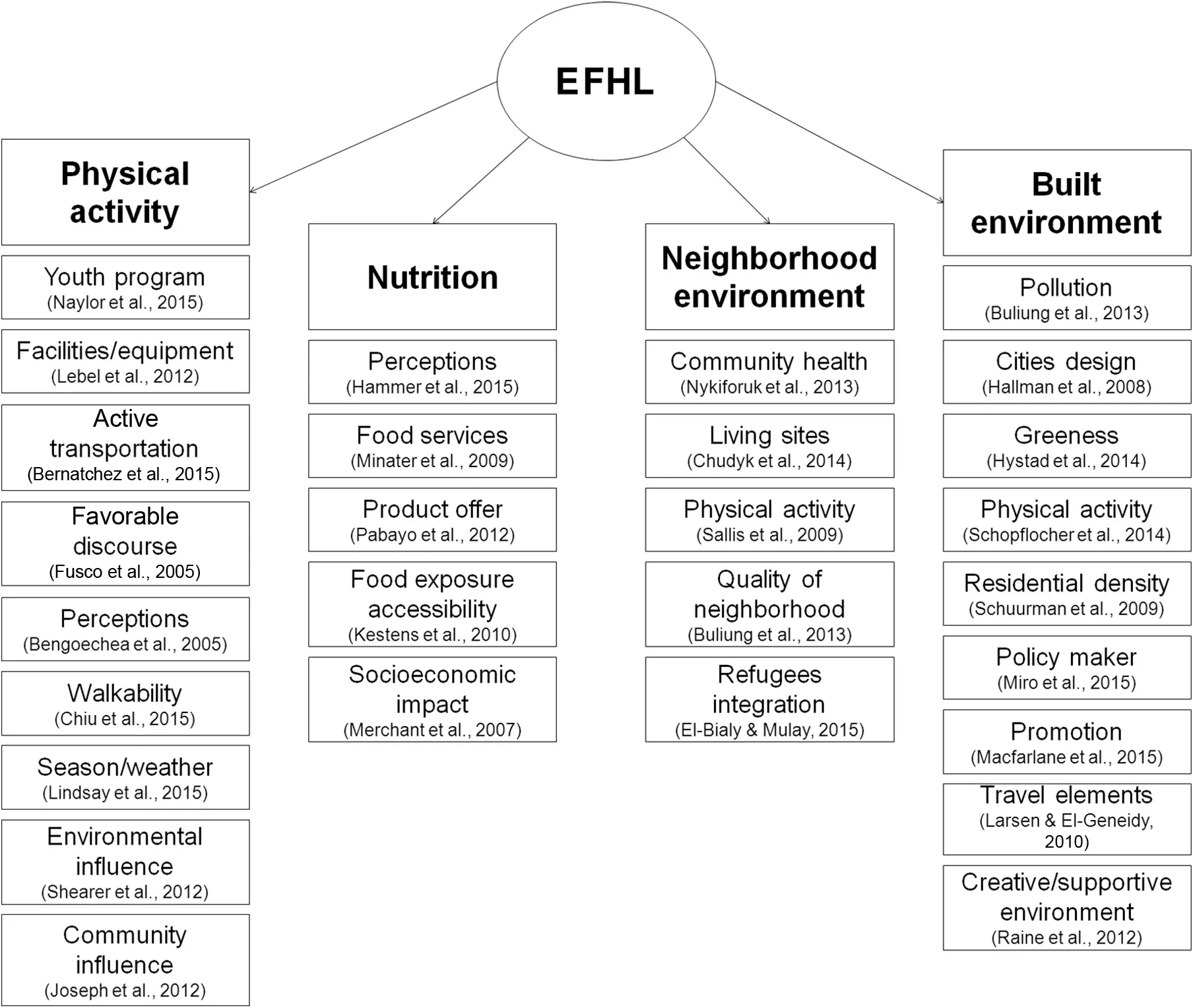

The issues addressed in terms of EFHL are complex and they frequently overlap.Seliske et al.,66for example,studied urban sprawl and its relationship to active transportation,physical activity,and obesity in Canadian youth.Nevertheless,4 major issues regarding EFHL stand out in Canadian studies:2 concerning healthy lifestyles(physical activity and nutrition)and 2 concerning environment(built environment and neighborhood)(Fig.2).These primary issues apparently define the EFHL concept in Canada in the scientific studies published during the period documented in our study.They can,in fact,be linked to the secondary issues(variables studied),which identified the EFHL components for each theme and sphere.Physical activity involved 9 variables:youth program,34,67,68accessibility to facilities and equipment,63,69-71activetransportation,58,72community influence,73discourse in favor of sport,74environmental influences,75perceptions,facilitators,and barriers,59,76season or weather,77and walkability.52,78Nutrition involved 5 variables:perceptions,79local food exposure and accessibility,80,81food services,28product offerings,29and the impact of a low socioeconomic status.82

Table 6Levels of intervention for the initiatives(n(%)).

Fig.2.Environments favorable to healthy lifestyles(EFHL)spheres and major variables studied.

Neighborhood environment included 8 variables:community organization and health,83,84living sites,85physical activity,86quality of neighborhood,61,87recreation,culture,and sport,54,60refugees integration,88school travel,89,90and seasonal influence.77,91

Finally,built environment involved 12 variables:air quality and pollution,92,93creative or supportive environment,94designing smart cities,36geographic transportation,90,95,96greenness,55,97,98physical activity,39policymaking perspectives,99-102promotion,103,104residential density,105risk of injury,40,49safety,106,107and travel distance,duration,and destination.47,50,106,107Although the majority of Canadian studies on EFHL analyzed can be divided into these 4 categories,discussions of other issues—smoking,for example—are totally absent or negligible.108,109

3.3.Evolution of the EFHL dimensions studied over the past 2 decades

The evolution of the number of EFHL studies over the past 10 years is illustrated in Fig.3.The chart confirms a rapid increase in EFHL studies since 2008,with numbers constantly improving.As shown in Table 7,the physical dimension dominates,but the other dimensions follow the same acceleration trend,with the exception of a small decline in 2013-2014.

4.Discussion

First of all,this review shows that the number of EFHL studies has risen sharply since 2010.A glance at the results for 2015 makes this obvious.Most studies on EFHL focus on the province of Quebec,followed by Ontario and British Columbia(Table 2).They support the findings of Savard et al.110that the majority of Canadian provinces,particularly Quebec,Ontario,and British Columbia,have implemented strategies to promote healthy lifestyles,especially as regards students in primary and secondary schools.The 2 main lifestyles affected by these strategies,programs,and interventions are healthy food choices and physical activity.We also observe that between 2010 and 2015,studies on the different dimensions of EFHL continue the same trend,even if most concentrate on the physical dimension(Fig.3).This sudden interest in EFHL seems strange insofar as no policies or action plans have been implemented in recent years by the federal,provincial,or territorial governments.It would be interesting to see if this trend holds true for countries other than Canada.It may be that international concern about sustainable development and the publication of studies on unhealthy lifestyles and their consequences are gradually raising awareness about the importance of EFHL.

Fig.3.Number of published studies on the 4 environments favorable to healthy lifestyles(EFHL)dimensions.

Second,this review found that EFHL models aim,on the whole,to improve 2 major lifestyles—physical activity and nutrition—in connection with different associated variables(a total of 14).Both relate,especially,to the physical dimension in the MSSS classification model(2012)and are confirmed by Fig.3.This leads us to question the silence surrounding other health issues(e.g.,tobacco,drugs,sleep,medication,mental health):Is this because Canadian researchers have completely overlooked these problems,or is it because of the limitations of the studies selected?In response,the review leaves the impression that stakeholders may prioritize physical activity and nutrition in their EFHL interventions,because these elements have a concrete relationship with the built environment.This hypothesis is confirmed by the findings we discuss next.With respect to environment,EFHL initiatives and actions occur in 2 major areas:the built environment and the neighborhood.Accordingly,Canadian research appears to define the concept of EFHL based on the environment(land use patterns,urban design characteristics,transportation system)and the influence of the local community and social relations.

Third,organizations or authors attempted to group EFHL initiatives into various types of categorizations.If the categorization of Booth et al.3seems to work in many cases(i.e.,international,national and provincial,regional,municipal,local),the categorization of the MSSS7appears too limited(i.e.,physical,political,sociocultural,economic)in that it fails to take underlying elements into account.Most of the studies in this review focus on the physical environment and tend to exclude other types of environment.To the authors’knowledge,both categorizations are limited in so far as they ignore key environments such as school,community,religion,socioeconomic status,family,and culture,among others.These elements would be helpful for designing a new research agenda with an improved classification that takes into account each EFHL parameter previously mentioned.

Finally,various design methods have been used to explore EFHL in the scientific literature in Canada.There were many situation reviews,but few reviews of the literature(n=6)(Table 3).In view of the rapid increase in studies,more literature reviews are recommended to guide future research.Adults(17-60 years)and young people(0-16 years)were studied to a greater extent than seniors.Some authors called for more research on the lifetime carry-over effects of EFHL initiatives targeting young people to see if there are effects after they become adults.111Furthermore,our findings reveal that studies on seniors are few and far between.This silence is problematic because the elderly population in Canada is growing rapidly,112and targeted solutions are needed.We also noticed there were few studies on girls and women(n=2),while attention was focused on other subjects(e.g.,food products,geographic areas,accident risk).These findings should prove beneficial for guiding future studies on EFHL.We observed,too,that municipal and local levels are mentioned far more often than national and provincial levels(Table 6),which poses a question about the involvement of provincial governments in designing and implementing EFHL initiatives.Our study indicates that cities,via their political authorities(e.g.,mayor,municipal advisor,councilman),are more proactive and are thus probably the best resources for solving the problem of sedentary lifestyles.113

In terms of EFHL development across Canada,recommendations for improving physical activity include facilitating and encouraging access to active transportation by means of safe and attractive infrastructures(e.g.,walking and cycling paths,parks,and services).57Municipal or local stakeholders can implement these initiatives by,for example,building sports facilities near residential neighborhoods in high and low income areas100and providing easy access to attractive sports facilities and equipment(e.g.,swimming pool,tennis courts).54,57To promote healthy lifestyles,they can provide safe access to services offering healthy choices and affordable prices114or design residential neighborhoods with easy access to multiple services and active transportation.94,102At the national and provincial levels,policies must foster collaboration between public health stakeholders and urban designers.The focus must be on facilitating access to infrastructures(e.g.,cycling paths,wheelchair access,walking access,lighting,and pedestrian crossings36,115and designing the built environment with a view to its impact on healthy lifestyles.116,117

In terms of guiding the new research agenda,future studies would do well to further concentrate on the subject of healthy lifestyles as discussed in research projects in Canada.They should document EFHL policies developed by federal and provincial governments and assist in developing new ones.Studies should explore official rules and policies for urbanization;produce impact studies on health dimensions(physical,mental,social);focus on urban planning based on considerations of healthy lifestyle;promote a better understanding of the impact of the built environment on gender,age,and class;and conduct macro(e.g.,food companies,car companies,and multilateral agreements websites,transportation policies)and micro analysis(e.g.,food shops proximity,school program,local rules for urbanization)related to EFHL.

This systematic review has certain limitations.First,the literature search was performed using 7 electronic databases and a substantial number of eligible articles.Because of the numerous articles found(n=264),it was difficult to summarize and present a uniform body of results,but this is unlikely to have affected findings very much.Second,the review is limited to research published in the scientific or gray literature.Accordingly,it excludes many concrete initiatives that were neither properly evaluated nor published in the scientific or gray literature.Finally,owing to the complexity of many topics covered under EFHL,there was little possibility of examining the links between studies,methods and findings,which underscores the necessity of developing a new EFHL classification.

5.Conclusion

This work offers a first map of Canadian studies on EFHL by presenting structured information on initiatives having to do with environments favorable to healthy lifestyles.It highlights the broad diversity of initiatives,the contexts in which they were implemented,and some negative effects of long-term interventions,which necessitates the involvement of numerous diverse stakeholders.Furthermore,it has led us to identify a new research agenda based on the need to classify EFHL and its components.The definition of EFHL was clarified,which resulted in a detailed exploration of issues,methodologies,stakeholders’involvement,and dimensions of the subject neglected up to now by researchers,namely,the political and sociocultural spheres of action.Our findings open the door to innovative research perspectives in future.

The authors want to thankQuébec en Formefor supporting this study.Authors also would like to thank Jean Jacques Rondeau for precious help performing the initial selection in the literature search based on abstract and title,and Louis Laurencelle for help performing the results analysis.

Authors’contributions

TG designed and conducted the study,literature search,data extraction,and data-analysis and drafted the manuscript;MB assisted in its design,data extraction and coordination,and helped draft the manuscript;FT and MCR discussed the paper,provided methodological input,and helped draft the manuscript.All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript,and agree with the order of presentation of the authors.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Appendix:Supplementary material

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at doi:10.1016/j.jshs.2017.09.005

1.American College of Sports Medicine.ACSM’s guidelines for exercise testing and prescription.7th ed.Baltimore,MD:Lippincott Williams&Wilkins;2005.

2.Frank LD,Engelke PO,Schmid TL. “Introduction”, “physical activity and public health”,and “urban design characteristics”.In:Larice M,Macdonald E,editors.The urban design reader.2nd ed.London:Routledge;2013.p.415-42.

3.Booth SL,Sallis JF,Ritenbaugh C,Hill JO,Birch LL,Frank LD,et al.Environmental and societal factors affect food choice and physical activity:rationale,influences,and leverage points.Nutr Rev2001;59(3 Pt 2):S21-39.

4.World Health Organization.Global recommendations on physical activity for health.Geneva:WHO Press;2010.

5.Bergeron P,Reyburn S,Laguë J.L’impact de l’environnement bâti sur l’activité physique,l’alimentation et le poids.Québec:Gouvernement du Québec;2010[in French].

6.Gadais T.Intervention strategies to help young people manage their physical activities:a review of the literature.Staps2015;3:57-77.

7.Ministère de la Santé et des Services sociaux.Pour une vision commune des environnements favorables à la saine alimentation,à un mode de vie physiquement actif et àla prévention des problèmes reliés au poids.Québec:Gouvernement du Québec;2012[in French].

8.World Health Organization.The Ottawa Charter for health promotion.Geneva:World Health Organization;1986.Available at:http://www.who.int/healthpromotion/conferences/previous/ottawa/en/; [accessed 15.07.2016].

9.Naylor PJ,McKay HA.Prevention in the first place:schools a setting for action on physical inactivity.Br J Sports Med2009;43:10-3.

10.Bellefleur O,Gagnon F.Apaisement de la circulation urbaine et santé:revue de littérature.Montréal:Centre de collaboration nationale sur les politiques publiques et la santé,Institut national de santé publique du Québec;2012[in French].

11.McCrorie PRW,Fenton C,Ellaway A.Combining GPS,GIS,and accelerometry to explore the physicalactivity and environment relationship in children and young people—a review.Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act2014;11:93.doi:10.1186/s12966-014-0093-0

12.Mowat DL.Healthy Canada by design:translating science into action and prevention.Can J Public Health2015;106(Suppl.1):eS3-4.

13.Robitaille É,Laguë J.Indicateurs géographiques de l’environnement bâti et de l’environnement des servives influant sur l’activité physique,l’alimentation et le poids corporel.Montréal:Institut national de santé publique du Québec;2009[in French].

14.Willows ND,Hanley AJG,Delormier T.A socioecological framework to understand weight-related issues in Aboriginal children in Canada.Appl Physiol Nutr Metab2012;37:1-13.

15.Sallis JF,Owen N,Fisher EB.Ecological models of health behavior.In:Glanz K,Rimer BK,Viswanath K,editors.Health behavior and health education:theory,research,and practice.4th ed.San Francisco,CA:Jossey-Bass;2008.p.465-86.

16.Frank L,Engelke P,Schmid T.Health and community design:the impact of the built environment on physical activity.Washington,DC:Island Press;2003.

17.Handy SL,Boarnet MG,Ewing R,Killingsworth RE.How the built environment affects physical activity:views from urban planning.Am J Prev Med2002;23:64-73.

18.Transport Research Board.2005annual report.Available at:http://onlinepubs.trb.org/onlinepubs/general/2005_TRB_Annual_Report.pdf;2005[accessed 15.05.2016].

19.Sallis JF.Measuring physical activity environments:a brief history.Am J Prev Med2009;36(4 Suppl.):S86-92.

20.Heath GW,Brownson RC,Kruger J,Miles R,Powell KE,Ramsey LT,et al.The effectiveness of urban design and land use and transport policies and practices to increase physical activity:a systematic review.J PhysAct Health2006;3(Suppl.1):S55-76.

21.Cervero R,Kockelman K.Travel demand and the 3Ds:density,diversity,and design.Transp Res D Transp Environ1997;2:199-219.

22.Belon AP,Nieuwendyk LM,Vallianatos H,Nykiforuk CI.How community environment shapes physical activity:perceptions revealed through the PhotoVoice method.Soc Sci Med2014;116:10-21.

23.Micklesfield LK,Lambert EV,Hume DJ,Chantler S,Pienaar PR,Dickie K,et al.Socio-cultural,environmental and behavioural determinants of obesity in black SouthAfrican women.Cardiovasc JAfr2013;24:369-75.

24.Villanueva K,Giles-Corti B,Bulsara M,Trapp G,Timperio A,McCormack G,et al.Does the walkability of neighbourhoods affect children’s independent mobility,independent of parental,socio-cultural and individual factors?Child Geogr2014;12:393-411.

25.Von Tigerstrom B,Larre T,Sauder J.Using the tax system to promote physical activity:critical analysis of Canadian initiatives.Am J Public Health2011;101:e10-6.

26.Beaudoin C.Twenty years of comprehensive school health:a review and analysis of Canadian research published in refereed journals(1989-2009).PHENex J2011;3:1-17.

27.Skinner K,Hanning RM,Tsuji LJ.Barriers and supports for healthy eating and physical activity for First Nation youths in northern Canada.Int J Circumpolar Health2006;65:148-61.

28.Minaker LM,Raine KD,Cash SB.Measuring the food service environment:development and implementation of assessment tools.Can J Public Health2009;100:421-5.

29.Pabayo R,Spence JC,Cutumisu N,Casey L,Storey K.Sociodemographic,behavioural and environmental correlates of sweetened beverage consumption among pre-school children.Public Health Nutr2012;15:1338-46.

30.Silverman S,Skonie R.Research on teaching in physical education:an analysis of published research.J Teach Phys Educ1997;16:300-11.

31.Gilbert WD,Trudel P.Analysis of coaching science research published from 1970-2001.Res Q Exerc Sport2004;75:388-99.

32.Nicholson SO.The effect of cardiovascular health promotion on health behaviors in elementary school children:an integrative review.J Pediatr Nurs2000;15:343-55.

33.Moher D,Liberati A,Tetzlaff J,Altman DG,PRISMA Group.Reprint—preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses:the PRISMA statement.Phys Ther2009;89:873-80.

34.Paradis G,O’Loughlin J,Elliott M,Masson P,Renaud L,Sacks-Silver G,et al.Coeur en santé St-Henri—a heart health promotion programme in a low income,low education neighbourhood in Montreal,Canada:theoretical model and early field experience.J Epidemiol Community Health1995;49:503-12.

35.Gauvin L,Richard L,Craig CL,Spivock M,Riva M,Forster M,et al.From walkability to active living potential:an “ecometric”validation study.Am J Prev Med2005;28(2 Suppl.2):S126-33.

36.Hallman BC,Menec V,Keefe J,Gallagher E.Making small towns age-friendly:what seniors say needs attention in the built environment.Plan Can2008;48:18-21.

37.Hanson HM,Schiller C,Winters M,Sims-Gould J,Clarke P,Curran E,et al.Concept mapping applied to the intersection between older adults’outdoor walking and the built and social environments.Prev Med2013;57:785-91.

38.Polsky JY,Moineddin R,Glazier RH,Dunn JR,Booth GL.Foodscapes of southern Ontario:neighbourhood deprivation and access to healthy and unhealthy food retail.Can J Public Health2014;105:e369-75.

39.Schopflocher D,VanSpronsen E,Nykiforuk CIJ.Relating built environment to physical activity:two failures to validate.Int J Environ Res Public Health2014;11:1233-49.

40.Schuurman N,Cinnamon J,Crooks VA,Hameed SM.Pedestrian injury and the built environment:an environmental scan of hotspots.BMC Public Health2009;9:233.doi:10.1186/1471-2458-9-233

41.Hobin E,Leatherdale S,Manske S,Dubin J,Elliott S,Veugelers P.A multilevel examination of factors of the school environment and time spent in moderate to vigorous physical activity among a sample of secondary school students in grades 9-12 in Ontario,Canada.Int J Public Health2012;57:699-709.

42.Leatherdale ST,Pouliou T,Church D,Hobin E.The association between overweight and opportunity structures in the built environment:a multi-level analysis among elementary school youth in the PLAY-ON study.Int J Public Health2011;56:237-46.

43.Carson V,Kuhle S,Spence JC,Veugelers PJ.Parents’perception of neighbourhood environment as a determinant of screen time,physical activity and active transport.Can J Public Health2010;101:124-7.

44.Gray CE,Barnes JD,Cowie Bonne J,Cameron C,Chaput JP,Faulkner G,et al.Results from Canada’s 2014 report card on physical activity for children and youth.J Phys Act Health2014;11(Suppl.1):S26-32.

45.Katapally TR,Muhajarine N.Capturing the interrelationship between objectively measured physical activity and sedentary behaviour in children in the context of diverse environmental exposures.Int J Environ Res Public Health2015;12:10995-1011.

46.Esliger DW,Sherar LB,Muhajarine N.Smart Cities,Healthy Kids:the association between design and children’s physical activity and time spent sedentary.Can J Public Health2012;103(Suppl.3):eS22-8.

47.Larsen J,El-Geneidy A.Beyond the quarter mile:re-examining travel distances by active transportation.Can J Urban Res2010;19(Suppl.1):S70-88.

48.Button B,Trites S,Janssen I.Relations between the school physical environment and school social capital with student physical activity levels.BMC Public Health2013;13:1191.doi:10.1186/1471-2458-13-1191

49.Mecredy G,Janssen I,Pickett W.Neighbourhood street connectivity and injury in youth:a national study of built environments in Canada.Inj Prev2012;18:81-7.

50.Millward H,Spinney J,Scott D.Active-transport walking behavior:destinations,durations,distances.J Transp Geogr2013;28:101-10.

51.Muhajarine N,Katapally TR,Fuller D,Stanley KG,Rainham D.Longitudinal active living research to address physical inactivity and sedentary behaviour in children in transition from preadolescence to adolescence.BMC Public Health2015;15:495.doi:10.1186/s12889-015-1822-2

52.Chiu M,Shah BR,Maclagan LC,Rezai MR,Austin PC,Tu JV.Walk score®and the prevalence of utilitarian walking and obesity among Ontario adults:a cross-sectional study.Health Rep2015;26:3-10.

53.de Sa E,Ardern CI.Neighbourhood walkability,leisure-time and transport-related physical activity in a mixed urban-rural area.PeerJ2014;2:e440.doi:10.7717/peerj.440

54.Carey M,Mason DS.Building consent:funding recreation,cultural,and sports amenities in a Canadian city.Managing Leis2014;19:105-20.

55.Blanchet-Cohen N.Igniting citizen participation in creating healthy built environments:the role of community organizations.Community Dev J2015;50:264-79.

56.Fuller D,Gauvin L,Fournier M,Kestens Y,Daniel M,Morency P,et al.Internal consistency,concurrent validity,and discriminant validity of a measure of public support for Policies for Active Living in Transportation(PAL-T)in a population-based sample of adults.J Urban Health2012;89:258-69.

57.Adams MA,Ding D,Sallis JF,Bowles HR,Ainsworth BE,Bergman P,et al.Patterns of neighborhood environment attributes related to physical activity across 11 countries:a latent class analysis.Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act2013;10:34-44.

58.Bélanger-Gravel A,Gauvin L,Fuller D,Drouin L.Implementing a public bicycle share program:impact on perceptions and support for public policies for active transportation.J Phys Act Health2015;12:477-82.

59.Bengoechea EG,Spence JC,McGannon KR.Gender differences in perceived environmental correlates of physical activity.Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act2005;2:12.doi:10.1186/1479-5868-2-12

60.Chaumette P,Morency S,Royer A,Lemieux S,Tremblay A.Environnements alimentaires des sites sportifs,récréatifs et culturels de la Ville de Québec:un portrait de la situation.Can J Public Health2009;100:310-14.[in French].

61.Coen SE,Ross NA.Exploring the material basis for health:characteristics of parks in Montreal neighborhoods with contrasting health outcomes.Health Place2006;12:361-71.

62.Coghill CL,Valaitis RK,Eyles JD.Built environment interventions aimed at improving physical activity levels in rural Ontario health units:a descriptive qualitative study Health policies,systems and management.BMC Public Health2015;15:464.doi:10.1186/s12889-015-1786-2

63.Roult R,Carbonneau H,Chan T,Belley-Ranger É,Duquette M-M.Physical activity and the development of the built environment in schools for youth with a functional disability in Quebec.Sport Sci Rev2014;23:225-40.

64.Robitaille É,Laguë J.Portrait del’environnement bâti et de l’environnement desservices:régionsociosanitaire(RSS)de l’Abitibi-Témiscamingue.Montréal:Institut national de santé publique du Québec;2011[in French].

65.Robitaille É,Laguë J.Portrait de l’environnement bâtiet de l’environnement desservices:régionsociosanitaire(RSS)de l’Outaouais.Montréal:Institut national de santé publique du Québec;2012[in French].

66.Seliske L,Pickett W,Janssen I.Urban sprawl and its relationship with active transportation,physical activity and obesity in Canadian youth.Health Rep2012;23:1-10.

67.Hobin EP,Leatherdale ST,Manske S,Dubin JA,Elliott S,Veugelers P.A multilevel examination of gender differences in the association between features of the school environment and physical activity among a sample of grades 9 to 12 students in Ontario,Canada.BMC Public Health2012;12:74.doi:10.1186/1471-2458-12-74

68.Naylor PJ,Olstad DL,Therrien S.An intervention to enhance the food environment in public recreation and sport settings:a Natural experiment in British Columbia,Canada.Child Obes2015;11:364-74.

69.Lebel A,Kestens Y,Pampalon R,Thériault M,Daniel M,Subramanian SV.Local context influence,activity space,and foodscape exposure in two Canadian metropolitan settings:is daily mobility exposure associated with overweight?J Obes2012;2012:912645.doi:10.1155/2012/912645

70.Lefebvre S,Roult R,Adjizian JM,Lapierre L.Planning and social appropriation of proximal sports facilities:the case of the exterior skating rink project Bleu Blanc Bouge in Montreal North.Loisir Soc2014;37:101-15.

71.Mecredy G,Pickett W,Janssen I.Street connectivity is negatively associated with physical activity in Canadian youth.Int J Environ Res Public Health2011;8:3333-50.

72.Bernatchez AC,Gauvin L,Fuller D,Dubé AS,Drouin L.Knowing about a public bicycle share program in Montreal,Canada:are diffusion of innovation and proximity enough for equitable awareness?J Transp Health2015;2:360-8.

73.Joseph P,Davis AD,Miller R,Hill K,McCarthy H,Banerjee A,et al.Contextual determinants of health behaviours in an aboriginal community in Canada:pilot project.BMC Public Health2012;12:952.doi:10.1186/1471-2458-12-952

74.Fusco C,.Cultural landscapes of purification:sports spaces and discourses of whiteness.Sociol Sport J2005;22:283-310.

75.Shearer C,Blanchard C,Kirk S,Lyons R,Dummer T,Pitter R,et al.Physical activity and nutrition among youth in rural,suburban and urban neighbourhood types.Can J Public Health2012;103(Suppl.3):eS55-60.

76.Benjamin K,Edwards N,Caswell W.Factors influencing the physical activity of older adults in long-term care:administrators’perspectives.J Aging Phys Act2009;17:181-95.

77.Lindsay S,Morales E,Yantzi N,Vincent C,Howell L,Edwards G.The experiences of participating in winter among youths with a physical disability compared with their typically developing peers.Child Care Health Dev2015;41:980-8.

78.Kaczynski AT,Glover TD.Talking the talk,walking the walk:examining the effect of neighbourhood walkability and social connectedness on physical activity.J Public Health(Oxf)2012;34:382-9.

79.Hammer BA,Vallianatos H,Nykiforuk CIJ,Nieuwendyk LM.Perceptions of healthy eating in four Alberta communities:a photovoice project.Agric Human Values2015;32:649-62.

80.Kestens Y,Lebel A,Daniel M,Thériault M,Pampalon R.Using experienced activity spaces to measure foodscape exposure.Health Place2010;16:1094-103.

81.Larsen K,Gilliland J.Mapping the evolution of ‘food deserts’in a Canadian city:supermarket accessibility in London,Ontario,1961-2005.Int J Health Geogr2008;7:16.doi:10.1186/1476-072X-7-16

82.Merchant AT,Dehghan M,Behnke-Cook D,Anand SS.Diet,physical activity,and adiposity in children in poor and rich neighbourhoods:a cross-sectional comparison.Nutr J2007;6:1.doi:10.1186/1475-2891-6-1

83.Nykiforuk CIJ,Nieuwendyk LM,Mitha S,Hosler I.Examining aspects of the built environment:an evaluation of a community walking map project.Can J Public Health2012;103(Suppl.3):eS67-72.

84.Nykiforuk CIJ,Schopflocher D,Vallianatos H,Spence JC,Raine KD,Plotnikoff RC,et al.Community Health and the Built Environment:examining place in a Canadian chronic disease prevention project.Health Promot Int2013;28:257-68.

85.Chudyk AM,Winters M,Gorman E,McKay HA,Ashe MC.Agreement between virtual and in-the- field environment audits of assisted living sites.J Aging Phys Act2014;22:414-20.

86.Sallis JF,Bowles HR,Bauman A,Ainsworth BE,Bull FC,Craig CL,et al.Neighborhood environments and physical activity among adults in 11 countries.Am J Prev Med2009;36:484-90.

87.Collins PA,Hayes MV,Oliver LN.Neighbourhood quality and self-rated health:a survey of eight suburban neighbourhoods in the Vancouver Census Metropolitan Area.Health Place2009;15:156-64.

88.El-Bialy R,Mulay S.Two sides of the same coin:factors that support and challenge the wellbeing of refugees resettled in a small urban center.Health Place2015;35:52-9.

89.Larouche R,Chaput JP,Leduc G,Boyer C,Bélanger P,Leblanc AG,et al.A cross-sectional examination of socio-demographic and school-level correlates of children’s school travel mode in Ottawa,Canada.BMC Public Health2014;14:497.doi:10.1186/1471-2458-14-497

90.Mitra R,Buliung RN.Built environment correlates of active school transportation:neighborhood and the modifiable areal unit problem.J Transp Geogr2012;20:51-61.

91.Lindsay S,Yantzi N.Weather,disability,vulnerability,and resilience:exploring how youth with physical disabilities experience winter.Disabil Rehabil2014;36:2195-204.

92.Buliung RN,Larsen K,Faulkner GEJ,Stone MR.The “path”not taken:exploring structural differences in mapped-versus shortest-network-path school travel routes.Am J Public Health2013;103:1589-96.

93.Marshall JD,Brauer M,Frank LD.Healthy neighborhoods:walkability and air pollution.Environ Health Perspect2009;117:1752-9.

94.Raine KD,Muhajarine N,Spence JC,Neary NE,Nykiforuk CIJ.Coming to consensus on policy to create supportive built environments and community design.Can J Public Health2012;103(Suppl.3):eS5-8.

95.Simen-Kapeu A,Kuhle S,Veugelers PJ.Geographic differences in childhood overweight,physical activity,nutrition and neighbourhood facilities: implications for prevention.CanJPublicHealth2010;101:128-32.

96.Yiannakoulias N,Bennet SA,Scott DM.Mapping commuter cycling risk in urban areas.Accid Anal Prev2012;45:164-72.

97.Hystad P,Davies HW,Frank L,Loon JV,Gehring U,Tamburic L,et al.Residential greenness and birth outcomes:evaluating the influence of spatially correlated built-environment factors.Environ Health Perspect2014;122:1095-102.

98.Potestio ML,Patel AB,Powell CD,McNeil DA,Jacobson RD,McLaren L.Is there an association between spatial access to parks/green space and childhood overweight/obesity in Calgary,Canada?Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act2009;6:77.doi:10.1186/1479-5868-6-77

99.Miro A,Perrotta K,Evans H,Kishchuk NA,Gram C,Stanwick RS,et al.Building the capacity of health authorities to influence land use and transportation planning: lessons learned from the healthy Canada by design clasp project in British Columbia.Can J Public Health2015;106(Suppl.1):eS40-9.

100.Olstad DL,Poirier K,Naylor PJ,Shearer C,Kirk SFL.Policy outcomes of applying different nutrient profiling systems in recreational sports settings:the case for national harmonization in Canada.Public Health Nutr2014;18:2251-62.

101.Olstad DL,Raine KD.Profit versus public health:the need to improve the food environment in recreational facilities.Can J Public Health2013;104:e167-9.

102.Pitter R.Finding the Kieran way:recreational sport,health,and environmental policy in Nova Scotia.J Sport Soc Issues2009;33:331-51.

103.Macfarlane RG,Wood LP,Campbell ME.Healthy Toronto by design:promoting a healthier built environment.CanJPublic Health2015;106(Suppl.1):eS5-8.

104.Schopflocher D,VanSpronsen E,Spence JC,Vallianatos H,Raine KD,Plotnikoff RC,et al.Creating neighbourhood groupings based on built environment features to facilitate health promotion activities.Can J Public Health2012;103(Suppl.3):eS61-6.

105.Schuurman N,Peters PA,Oliver LN.Are obesity and physical activity clustered a spatial analysis linked to residential density.Obesity(Silver Spring)2009;17:2202-9.

106.Côté-Lussier C,Mathieu ME,Barnett TA.Independent associations between child and parent perceived neighborhood safety,child screen time,physical activity and BMI:a structural equation modeling approach.Int J Obes2015;39:1475-81.

107.Nichol M,Janssen I,Pickett W.Associations between neighborhood safety,availability of recreational facilities,and adolescent physical activity among Canadian youth.J Phys Act Health2010;7:442-50.

108.Kaai SC,Brown KS,Leatherdale ST,Manske SR,Murnaghan D.We do not smoke but some of us are more susceptible than others:a multilevel analysis of a sample of Canadian youth in grades 9 to 12.Addict Behav2014;39:1329-36.

109.Kaai SC,Manske SR,Leatherdale ST,Brown KS,Murnaghan D.Are experimental smokers different from their never-smoking classmates?A multilevel analysis of Canadian youth in grades 9 to 12.Chronic Dis Inj Can2014;34:121-31.

110.Savard D,Rivard M-C,Lamothe D,Boulanger M,Gomez V,Cissé AL,et al.Rapport d’évaluation—politique-cadre pour une saine alimentation et un mode de vie physiquement actif—pour un virage santé àl’école.Québec:Ministère de l’Éducation,du Loisir et du Sport;2014[in French].

111.Power C,Manor O,Matthews S.The duration and timing of exposure:effects of socioeconomic environment on adult health.Am J Public Health1999;89:1059-65.

112.Statistique Canada.Estimations de la population du Canada:âge et sexe,1er juillet 2015.Available at:http://www.statcan.gc.ca/daily-quotidien/150929/dq150929b-fra.htm;2015[accessed 16.05.2016][in French].

113.Lawrence RJ,Fudge C.Healthy cities in a global and regional context.Health Promot Int2009;24(Suppl.1):i11-8.

114.Veugelers P,Sithole F,Zhang S,Muhajarine N.Neighborhood characteristics in relation to diet,physical activity and overweight of Canadian children.Int J Pediatr Obes2008;3:152-9.

115.Winters M,Brauer M,Setton EM,Teschke K.Built environment influences on healthy transportation choices:bicycling versus driving.J Urban Health2010;87:969-93.

116.Zahabi S,Strauss J,Manaugh K,Miranda-Moreno L.Estimating potential effect of speed limits,built environment,and other factors on severity of pedestrian and cyclist injuries in crashes.TranspResRec2011;2247:81-90.

117.Ulmer JM,Chapman JE,Kershaw SE,Campbell M,Frank LD.Application of an evidence-based tool to evaluate health impacts of changes to the built environment.Can J Public Health2014;106(Suppl.1):eS26-32.

Journal of Sport and Health Science2018年1期

Journal of Sport and Health Science2018年1期

- Journal of Sport and Health Science的其它文章

- Research highlights from the Status report for step it up!The surgeon general’s call to action to promote walking and walkable communities

- The built environment correlates of objectively measured physical activity in Norwegian adults:A cross-sectional study

- The association of various social capital indicators and physical activity participation among Turkish adolescents

- Feasibility of using pedometers in a state-based surveillance system:2014 Arizona Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System

- Matched or nonmatched interventions based on the transtheoretical model to promote physical activity.A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials

- Collegiate athletes’mental health services utilization:A systematic review of conceptualizations,operationalizations,facilitators,and barriers