Collegiate athletes’mental health services utilization:A systematic review of conceptualizations,operationalizations,facilitators,and barriers

Jennifer J.Morelnd,Kthryn A.Coxe,Jingzhen Yng,c,*

aThe Research Institute at Nationwide Children’s Hospital,Columbus,OH 43205,USA

bOhio Department of Mental Health&Addiction Services Office of Quality,Planning&Research,Columbus,OH 43215,USA

cDepartment of Pediatrics,College of Medicine,The Ohio State University,Columbus,OH 43210,USA

1.Introduction

Collegiate student-athletes represent a unique population of young adults.Distinct from their non-athlete peers,collegiate student athletes must manage the challenges of college academics while maintaining a peak physical fitness level and the responsibilities associated with sports team membership.1Such strenuous demands put male and female collegiate student athletes at potential risk for various mental health concerns.2According to data from the National College Health Assessment surveys,about 31%of male and 48%of female National Collegiate Athletic Association(NCAA)student-athletes reported either depression or anxiety symptoms each year of the 2008 and 2012 academic years.3Evidence also shows that collegiate athletes are at risk for clinical or subclinical eating disorders,4,5substance abuse,6gambling addictions,7sleep disturbances,mood disorders,and even suicide.3To address increasing concern regarding athletes’mental health,the Association for Applied Sports Psychology(AASP)and the NCAA Sports Science Institute both called for more research studies focused on improving collegiate athletes’mental health and overall well-being.In March 2016,the NCAA outlinedMental Health Best Practicesthat athletic departments must enact to raise awareness of mental health services availability,employ various types of mental health care providers,create referral systems,and utilize “pre-participation mental health screening”.8

Prior research demonstrates the utility of examining athletics participation and athletes’health through a socio-ecological lens.9,10Per the socio-ecological framework,individuals make health decisions and enact health behaviors inside a complex social environment;the social environment influences these individuals and they,in turn,affect their social environment.11Athletes hold and act on their own attitudes,beliefs,and opinions regarding mental health.Additionally,the attitudes and perceptions of people close to these athletes impact their healthoriented opinions and actions.Those affecting the athletes’health decision-making are considered stakeholders and include the athletes’social groups and the cultural environment around the athlete.12,13In the case of the collegiate student athlete,the sociocultural views on mental health held by teammates,friends,family members,athletic trainers,coaches,as well as the local,regional,and national athletics administrative environment,impact how the athlete will respond to mental health-related challenges.2,3Likewise,more athletes utilizing mental health services,in turn,should impact the stakeholders’cultural views and responses to collegiate athletes’mental health service needs.

Student athletes,unlike their non-athlete collegiate peers,must balance the simultaneous rigors of academic and athletic life and transition to the independence of adulthood while maintaining family,friend,and peer networks.The pressure to perform well in all facets of life impacts collegiate athletes academic and on- field performances.14,15Research demonstrates college students often do not recognize or admit personal mental illness symptoms or are unaware of available mental health services(i.e.,counseling,psychotherapy,comprehensive treatment plans).16,17The social stigma associated with seeking mental health treatment can be an overwhelming barrier.18While collegiate athletes did report being more willing to seek help for a future mental health concern than their non-athlete counterparts,collegiate athletes were less likely to report receipt of mental health care.3The perceptions and norms of the athletic team(e.g.,teammates,coaches,and athletic trainers),and the social and cultural environment(e.g.,athletic department,university)around the athletes impact how athletes view mental health care and those who seek mental health services.19-23Institutionally and environmentally,some college athletic facilities may lack appropriate resources tailored to the student athlete in terms of confidentiality,convenience,and cultural sensitivity.Likewise,even if an athletic department or student services center provides student athletes mental healthcare resources,the care provider charged with caring for the athletes may be under qualified24or stretched too thin.

Researchers,university officials,athletics programs,and policy makers are dedicating more time and resources to addressing the prevalence and care of collegiate athletes’mental health concerns.25-28Recent research showed athletic administrators were willing to hire sport psychology professionals to aide collegiate athletes enhance on- field performance,as well as career and personal development.29Athletic administrators’knowledge and personal preferences can directly impact the type of mental health professional hired or contracted to counsel athletes.30,31It is important to note that mental health services offered to collegiate athletes may be performed by a variety of professionals including sport psychologists,sport psychology consultants,licensed clinical social workers,psychiatrists,psychiatric mental health nurses,licensed mental health counselors,mental skills trainers,mental resilience specialists,and even primary care physicians trained specifically to manage mental health disorders.Such professionals possess varied educational and training backgrounds and may provide highly individualized support and treatment or more generalized team support.For instance,sport psychologists usually hold a doctoral degree accredited by the American Psychological Association and are trained to work with collegiate athletes on mental health related issues,including depression,anxiety,or substance abuse.On the other hand,sport psychology consultants often hold a master’s degree,are certified in sport psychology,and are trained to work with collegiate athletes on athletic performance related issues(AASP).8,32,33

A systematic look at how key stakeholders in athletes’lives affect mental health services utilization(MHSU)is missing from this area of research.Likewise,the literature is incomplete regarding the beliefs collegiate student-athletes hold regarding using mental health services and how these views shape their behaviors.Together,the personal characteristics,attitudes,and beliefs of the athletes and stakeholders may ultimately influence mental health service utilization and,subsequently,improved mental health outcomes in the collegiate athlete population.The aims of this systematic review were to(1)analyze existing literature concerning collegiate athletes’use of mental health services by summarizing conceptualizations and operationalizations of mental health services in current literature and(2)understand the facilitators of and barriers to use of mental health services by collegiate athletes through a socio-ecological lens.

2.Methods

2.1.Search strategy

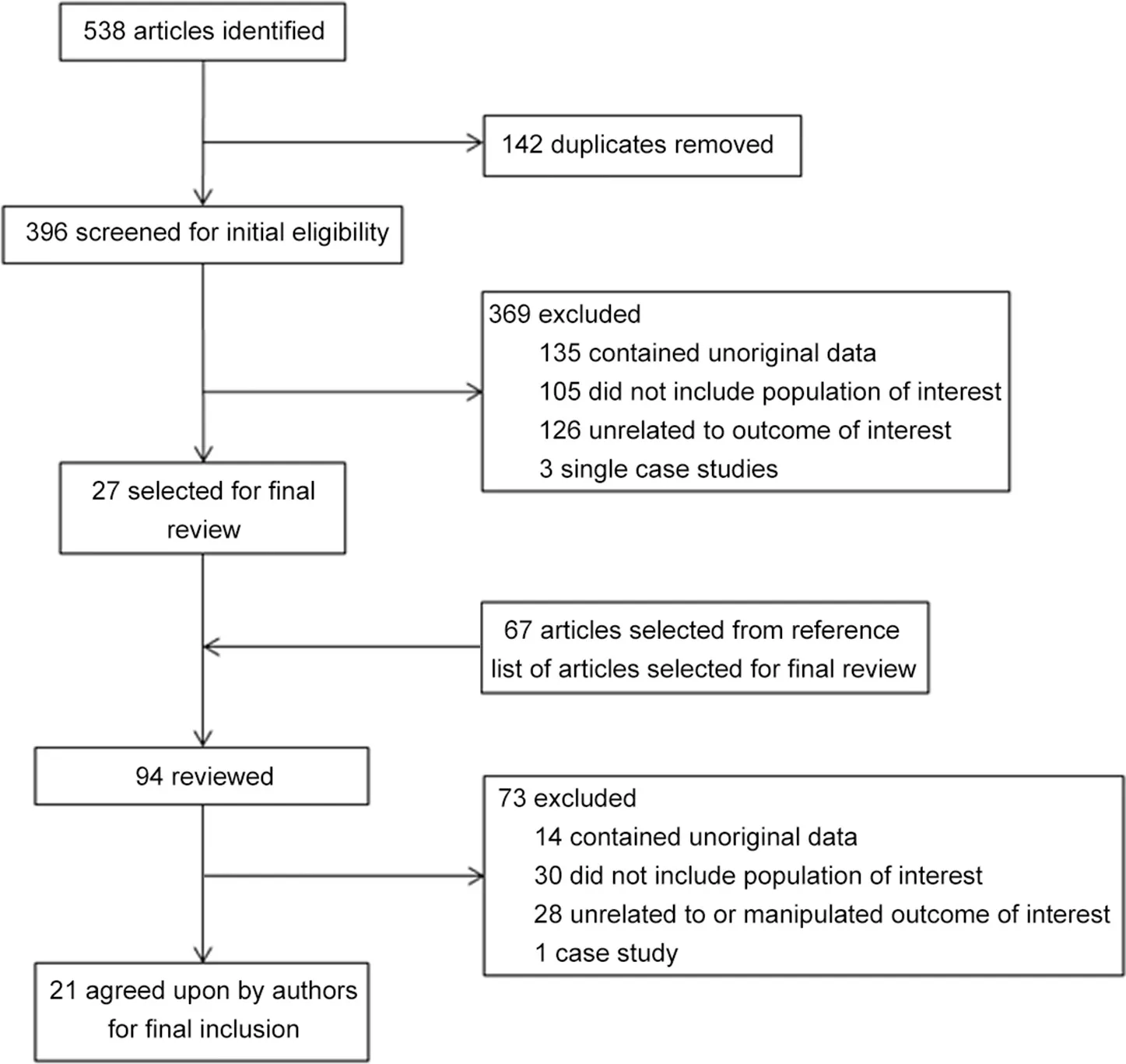

The current systematic review was conducted following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses(PRISMA)guidelines.Studies were identified through the use of 5 databases:Academic Search Complete;ERIC;Health Source:Nursing/Academic Addition;PubMed;and PsychINFO.34,35The literature search was limited to English-language,peer-reviewed journal articles published between January 2005 and December 2016 concerning U.S.collegiate athletes.The 11-year timeframe studied was selected because a historical picture of athletes’MHSU was not the focus of current study and not until 2013 did the NCAA host its first-ever Mental Health Task Force.36Non-U.S.collegiate and university athletes may interpret mental health treatment differently compared to U.S.collegiate and university athletes.World Health Organization statistics demonstrate the U.S.carries a higher depression burden than Australia,the UK,and parts of Asia37and,not until 2012 were private U.S.health insurers required to cover patients’mental health services.38Searches were constrained to the following key terms:college athlete,collegiate athlete,college student athlete,andcollegiate student athletepaired(using the Boolean“AND”function)withcounseling,counseling assistance,counseling services,counselor treatment,mental health assistance,mental health care,mental health services,mental health treatment,psychologicalhealth assistance,psychological care,psychological health services,andpsychological treatment.Searching the 5 databases rendered 538 articles and 142 duplicates were removed.

Fig.1.Flow of article assessment from initial selection to final inclusion.

2.2.Selection process

The following inclusion criterion were used for article selection:(a)published between January 2005 and December2016,(b)contained an analysis of original data(i.e.,did not pertain to a systematic review,meta-analysis,or secondary data analysis),(c)included the study population of interest(i.e.,U.S.collegiate athletes and key stakeholders in the athletes’lives),and(d)addressed some form of a conceptualization and operationalization of MHSU(e.g.,use of or a referral made to a mental health services provider).The authors chose to include studies with samples of individuals who work with or support the collegiate athletes and are known to influence the health decision making of collegiate athletes,such as coaches,parents,athletic trainers,and sports administrators to reflect components of the socio-ecological framework.23,39Following the elimination of duplicates,396 articles were first screened to ensure they contained original data; 135were eliminated. Studies not pertaining to U.S.collegiate athletes were excluded(n=105).Next,126 articles without a conceptualization or operationalization of collegiate athletes’MHSU and 3 single case studies were eliminated,which resulted in 27 articles for consideration for the final sample.

Next,a “hand search”was conducted on the references of the 27 articles pulled to ensure thorough coverage.Sixty-seven articles were obtained through the hand literature search and were reviewed.Subsequently,94 articles were reviewed by the authors and 73 were eliminated using the same criterion mentioned above(Fig.1).Thus,21 articles were included for the final analysis,as agreed upon by all authors.

3.Results

3.1.Article analysis

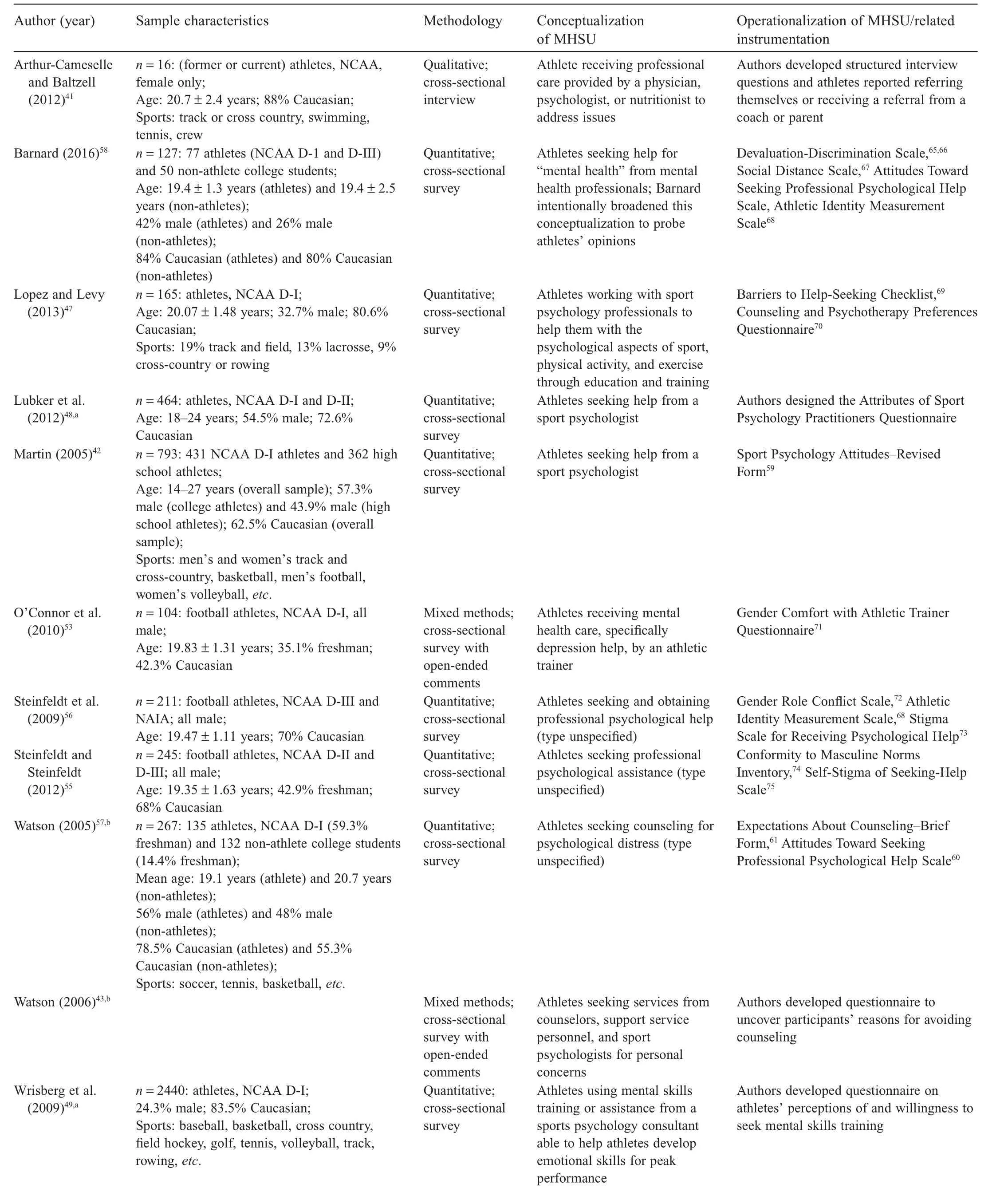

The first and second authors analyzed 5 randomly selected articles from the final pool of 21 articles to obtain agreement on the manner in which articles were categorized and analyzed.The remaining articles were divided between the first and second authors for initial analysis.All authors reviewed and agreed upon the contents included in the 2 extraction tables.As recorded in Table 1,the authors reviewed and discussed each study’s objectives,methods,results,and discussion points,as well as each study’s conceptualization and operationalization of MHSU.For the purpose of this systematic review,past,current,or intended use of MHSU;referrals made to mental health and/or sport psychology services;and any use of measurement tools were analyzed and recorded.

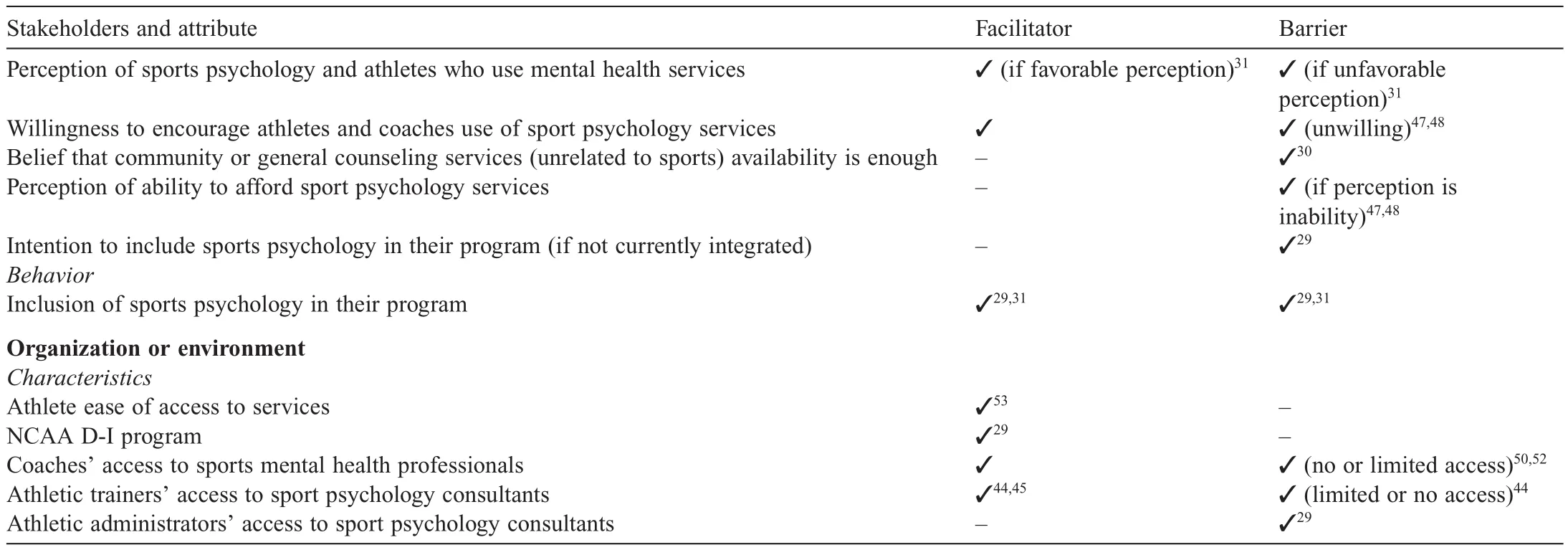

To mirror the socio-ecological framework,facilitators and barriers to athletes’MHSU were assessed(Table 2).Factors that promoted collegiate athletes’positive attitudes toward,willingness to seek,and willingness to utilize mental health services were considered facilitators to MHSU.Likewise,factors that impeded collegiate athletes’MHSU by discouraging the athlete,for instance,through negative attitudes or beliefs by coaches that athletes should remain “tough”,were considered barriers.Facilitators and barriers were arranged in order of the stakeholders’proximity to the athlete.40In other words,individuals and groups who directly affect the athlete were placed closer to the athlete and those with more diffuse influence placed further from the athlete.Parents,teammates,and coaches were conceptually placed nearer the athlete,as they interact with the athlete regularly.Subsequently,athletes’facilitators of and barriers to MHSU were analyzed followed by the parents’,team-(mates)’,coaches’,athletic trainers’,and administrators’influence and organizational or environmental factors(Table 2).

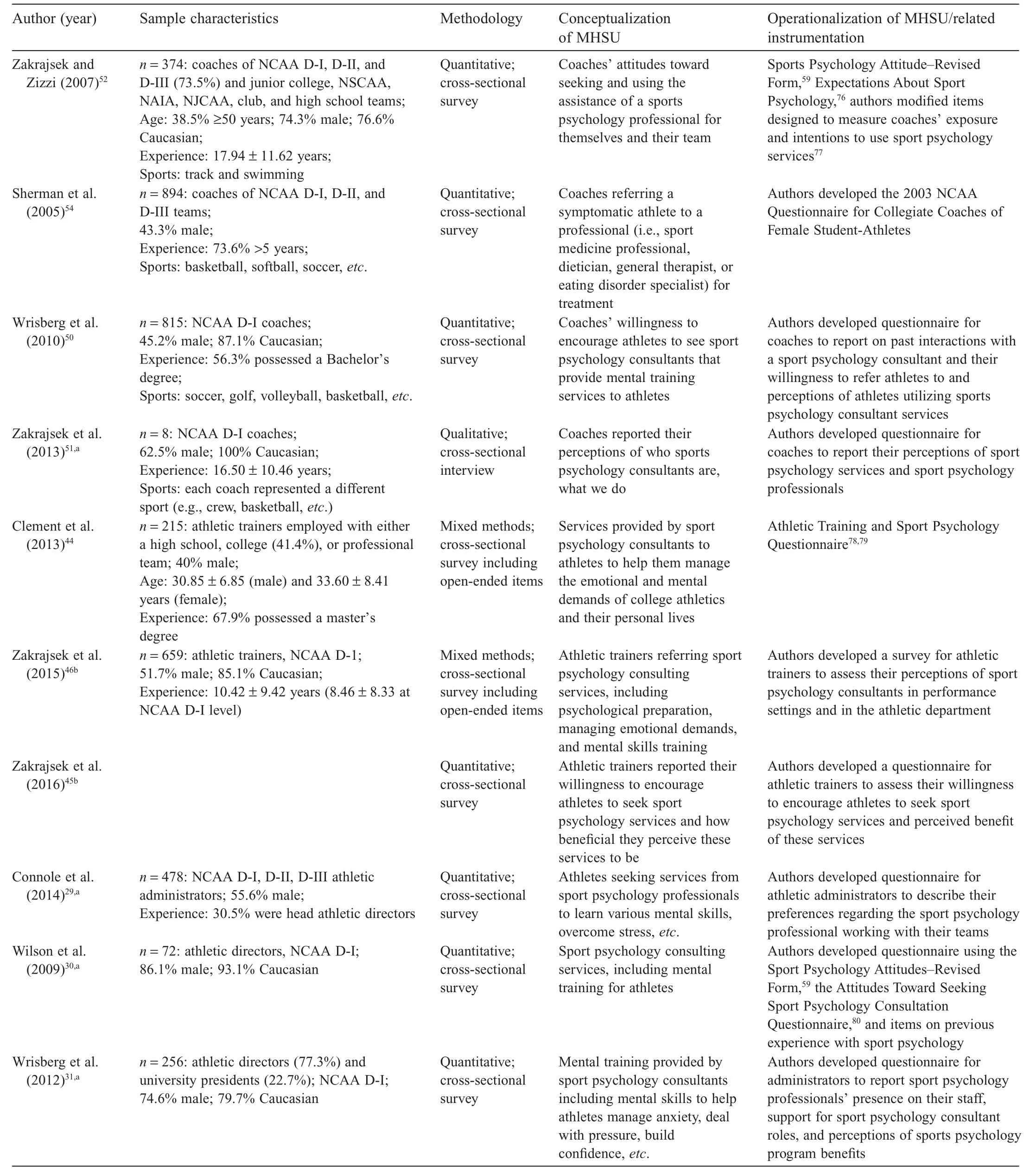

Table 1Description of studies included in the review.

(continued on next page)

Table 1(continued)

Table 2Stakeholders assessed as facilitators of or barriers to athletes’mental health services utilization,or both.

(continued on next page)

Table 2(continued)

Contrastingly,athletic administrators influence the collegiate athlete through policy,but less so via interpersonal interaction.Facilitators and barriers were further sorted per stakeholders’personal characteristics;attitudes and opinions;and past behaviors.Characteristics of the organization environment surrounding the athlete were also analyzed and listed either as a facilitator or barrier.Analyses and creation of tables were completed through an iterative process with all authors engaged in multiple rounds of analysis through discussion,refining,and critiquing,before consensus was reached.

3.2.Study characteristics

A total of 21 published manuscripts describing results of 19 unique studies were originally published in 12 different journals.All 19 studies were cross-sectional in nature.Fifteen studies were conducted using quantitative survey methodology,2 studies involved qualitative interview analysis,and 4 studies employed mixed methods(Table 1).

The populations of primary interest in these studies were collegiate athletes(n=11);coaches at all levels(i.e.,head,associate,assistant)(n=4);athletic trainers(n=3);and athletic administrators at all levels(i.e.,director,associate,assistant)(n=3).Eight studies included NCAA D-I athlete participants,2 included NCAA D-II athlete participants,2 included D-III athletes(where D-I,D-II,and D-III indicate Division 1,2,and 3 respectively),and only 1 study included National Association of Intercollegiate Athletics(NAIA)athlete participants.Four studies examined athlete participants from a combination of NCAA or NAIA programs and authors of just 1 study did not further classify athlete participants beyond “former or current”NCAA female athletes.41Authors of 1 paper did not provide more information on their athlete participants other than general NCAA athletics participation.41One study included high school athletes as a comparison group42and another compared collegiate athletes with nonathlete college students.43Athlete and coach participants represented a wide array of sports including basketball,crew,football,soccer,tennis,track and field,etc.Athletic trainers were the subjects of 3 studies in this review and primarily represented NCAA D-I athletic program athletic trainers.44-46Importantly,none of the studies included simultaneously examined collegiate athletes and members of a related population(e.g.,coaches or athletic trainers)(Table 1).

3.3.Conceptualization and operationalization of MHSU

Authors of the 21 papers included in this review conceptualized collegiate athlete MHSU with considerable variability(Table 1).Most articles conceptualized athletes’MHSU as the athlete receiving services from a sport psychology professional or consultant.29-31,42-52Four of this subgroup of papers clearly delineated sport psychologists from other sport psychology professionals in conceptualizing MHSU.42,45-47However,authors of other articles conceptualized collegiate athlete MHSU as services received from wide range of providers including a general counseling services provider or a professional other than a traditional mental health services provider,such as an athletic trainer,physician,sports medicine personnel,nutritionist and dietician,or eating disorder specialist.53-55Three research papers viewed athletes’MHSU very generally as counseling and/or professional psychological assistance.55-57Four papers further specified sport psychology consulting or care as“mental skills training”or“mental training”.29-31,50The author of only 1 study in this review chose to explore how athlete participants themselves“conceptualize mental illness when not given any cues”(p.164).58

Of 21 articles reviewed,MHSU was operationalized as(1)athletes’and stakeholders’past,current,or intended MHSU and(2)stakeholders’referral of athletes to mental health services.For example,some authors asked athlete respondents if they used sports psychology services in the past and if so,whether or not they found services to be helpful42or intended to use these services in the future.48O’Connor and colleagues53reported on athletes’comfort with seeking mental health assistance from athletic trainers.Seven studies operationalized MHSU as a coach or athletic trainer encouraging use of or referring symptomatic athletes to mental health care providers in the past.44-46,50-52,54Zakrajsek and colleagues’studies51,52explored whether or not coaches would be willing to refer one of their athletes to a mental health services provider.Athletic administrators and directors were not asked to report on their referral of athletes to mental health services,likely due to the distal nature of administrators and directors to athletes.29-31

Over half(n=11)of the studies reviewed employed previously validated measurement tools to assess athletes’perceptions of,attitudes toward,and preferences concerning MHSU,as well as relevant psychosocial phenomenon.To examine athletes’and stakeholders’views of counseling or sport psychology,the Sport Psychology Attitudes-Revised Form,59Attitudes Toward Seeking Professional Psychological Help Scale,58,60or the Expectations About Counseling-Brief Form were used.61Some researchers also examined the concepts related to MHSU and their associations with actual behaviors of MHSU,such as personality identity,athletic identity,or gender role conflict(Table 1).

3.4.Facilitators of and barriers to mental health services

A number of attributes emerged as facilitators of and barriers to collegiate athletes’MHSU at the individual level(Table 2).Athletes possess personal characteristics, attitudes, and opinions toward MHSU,and have enacted past behaviors that further describe the facilitator and barriers.Overall,athletes reported a number of attitudes toward and opinions potentially facilitating or barring their MHSU,but only a few personal characteristics(i.e.,gender,gender role or identity adherence,and sport type)and 1 behavior(i.e.,prior experience with mental health services49)that could influence MHSU intentions.More specifically,males over females,42,47,49,56and males with a strong adherence to masculine ideas,55,56were less likely to report a willingness to seek mental health or sports psychology services.Collegiate athletes’desire to work with a sport psychologist or mental health services provider with particular personal characteristics;47,48perceptions of personal need for and expectations around receiving mental health services;26,51and(un)willingness to seek services49,57were examined.

Study results showed stakeholders such as athletes’parents,coaches,teammates,athletic trainers,administrators,and the collegiate sporting environment facilitate or inhibit these athletes’attitudes and opinions and behavior toward MHSU(Table 2).For example,coaches and administrators hold expectations of what mental health or sport psychology consulting can do for athletes and some reported negative perceptions of athletes who utilized mental health services.Two studies found coaches’desire to maintain control over team dynamics seemed to override their willingness to employ sport psychology or mental health services with their team.51,54However,a few studies demonstrated a lack of stigma or supportive attitude toward team or individual athletes’MHSU could facilitate MHSU.Some coaches discussed in these studies reported utilizing mental health services for their team,which likely exposed athletes to the practice and benefits of MHSU.

The influence of parents and teammates and how their role can influence the athlete by referring him or her to the appropriate mental health service provider was mentioned in only 1 article.41Likewise,athletic trainers,the focus of 3 studies in this review,44-46were willing overall to refer athletes to sport psychology services,made service referrals,and many believed the presence of a sport psychology consultant on staff in an athletic department to be helpful to the athletes.Unfortunately,some athletic trainers surveyed in the study by Clement et al.44reported they lacked a formal referral process inside their athletic department.Athletic administrators and directors wield considerable control over access to and type of mental health services provided to their student athletes.Yet,some administrators report an inability—whether real or imagined—to provide collegiate athletes with dedicated mental health services geared toward the athlete.Some administrators believe community or general counseling,already offered at the university,is sufficient for sport-related mental health concerns.However,some administrators report support for and a willingness to refer athletes to a sport psychology professional.Overall,the organizational structure of the athletic program and the characteristics,attitudes,opinions,and behaviors of those close to the athlete will impact whether an athlete chooses to utilize mental health services.

Analyses demonstrate a number of facilitators and barriers(1)crosscut athlete status and stakeholder type and(2)functioned as facilitators in some cases,but as barriers in others.Females were,overall,more in favor of and acted positively toward use of mental health services.Specifically,female athletes were found to be more willing to seek help from a mental health services professional and female coaches and athletic trainers were more likely to refer the athlete for assistance.Male gender and stronger male gender identity was associated with less willingness to seek or refer mental health care assistance.Interestingly,however,Barnard’s recent research showed collegiate athletes were more accepting of others with mental illness compared to their non-athlete counterparts.58Athletes’and coaches’past experience with mental health or sport psychology consulting facilitated their willingness to use such services in the future,granted the experience was positive;negative past experiences functioned as barriers.Attitudes toward referring athletes to mental health or sports psychology services emerged as a prominent facilitator and barrier for coaches,athletic trainers,and administrators.While some athletes and stakeholders were less favorable toward sports psychology or mental health counseling,several papers described parents’,teammates’,coaches’,and athletic trainers’past referral to a mental health professional.Such referrals facilitated the athletes’MHSU.

4.Discussion

For as much as is known regarding the existence of mental health issues among collegiate student athletes,the literature currently lacks a complete picture of collegiate athletes’utilization of mental health services.The goals of the present review were to document the literature in the over the past 11 years concerning collegiate athletes’utilization of mental health services and to summarize the facilitators and barriers associated with the use of mental health services by members of this population.Assessments were situated within a socioecological framework to consider the unique context in which collegiate athletes study and perform and to obtain a comprehensive view of how individuals’attitudes,beliefs,and behaviors influence and are influenced by external circumstances.19,62The findings from this systematic review show athletes are at least somewhat willing to seek professional counseling or therapeutic care for mental health concerns,but face numerous personal barriers,as well as interpersonal and environmental barriers in doing so.

Articles in this study demonstrate the variability of conceptualizations and operationalizations of MHSU,which makes comparing the results across studies difficult.Some authors conceptualized MHSU as athletes seeking and then choosing care primarily from mental health counselors or sport psychology consultants.41,43,47,48,55,57However,other authors defined athletes’MHSU as a stakeholders’referral or willingness to make a mental health services referral.44-46,54Such variability demonstrates a lack of conceptual clarity regarding the definition of athletes’MHSU,which should include the type of service provider,format,and financer(e.g.,student health insurance,athletic department,etc.).Operationalizing athletes’MHSU is likely difficult due to the diversity and lack of knowledge of the fields of counseling and psychology with regard to professionals’educational backgrounds and expertise.As mentioned,members of several professions can and do treat or support collegiate athletes for mental health-related concerns,but their services should not be considered equal.Extant literature demonstrates that athletic administrators may be aware that their athletes need deepened sport psychology-type services,but be unclear as to which sport psychology professionals to hire to fulfill the needs of their collegiate athletes.Unfortunately,some administrators continue to hire and create earning structures for sport psychologists based on their personal philosophies surrounding MHSU.3,18

Measurement of MHSU in recent literature is also inconsistent with authors utilizing previously validated tools,creating their own tools(either not validated or validated inside their article),or using a combination of both.Subsequently,it is simultaneously challenging to assess when,where,how,and why collegiate athletes seek and use mental health services and compare advances in this research area.Future studies should seek to create and validate more measurement tools to study college athletes’MHSU.Likewise,more research is needed into the strength of a potential relationship between willingness to use and actual use of sports psychology or mental health consulting services.Use willingness or intentions are not measurement proxies for athletes’actual MHSU.

While athletes could potentially alter their own attitudes toward and expectations of seeking and receiving sports psychology or mental health services counseling,some facilitators and barriers are beyond the student athletes’control.First,a large body of research demonstrates the attitudes and opinions of leaders often become cultural norms influencing the actions of those within their sphere of influence.Subsequently,to further encourage athletes to seek the assistance of sports psychologists or counselors,the norms surrounding MHSU need to be changed.Second,institutionally,athletic administrators should seek to(re)allocate funds to support the development or furthering of sports psychology consulting programs and staffing.While athletic administrators are more distal stakeholders in the lives of athletes,they assert profound influence over athletic programmatic structure.Athletic administrators should reassess metrics of success for the sport psychologist beyond athletes performing better on the field.On- field performance improvement is certainly key,but the overall betterment of athletes’mental health status and well-being is of utmost importance.

Lopez and Levy47and Lubker et al.48both found collegiate athletes prefer counselors with a sports background and report being more likely to utilize mental health services when their preference can be or is met.While it is important to aim for patient-counselor concordance(i.e.,with regard to gender,race,background,etc.)on as many dimensions as possible,perhaps stakeholders should more often consider the acuity of an athlete’s mental health concern.Likewise,stakeholders surrounding the athlete should encourage the athlete willing to utilize mental health service to be open to various counseling approaches and formats,given availability of athletic department or team resources.

Review of the current literature on collegiate athletes and MHSU suggests the need for further analysis concerning the influence various stakeholders have—formally or informally—on collegiate athletes.None of the studies included in this systematic review examined sport psychologists’or mental health counselors’perspectives on their encounters with collegiate athletes and what specific practices enable successful treatment of their clients.Only 3 studies in the current review specifically studied the perceptions of athletic trainers who care for only college athletes.44-46Athletic trainers are known to influence athletes with regard to health behavior decision-making63and thus warrant further research attention.Likewise,recent research shows teammates can provide social support to injured teammates and aid them in their recovery process.64

Subsequently,future research should seek to examine facilitators of and barriers to collegiate athletes’MHSU using a more dyadic approach,such that athletes and stakeholder perceptions and behaviors are measured in tandem.In other words,while it is helpful to explore stakeholders’opinions on various mental health services useful for athletes,athletes may be better served by understanding how various implicit and explicit messages communicated by stakeholders impact athletes actual MHSU.Future studies may also consider developing and evaluating effective intervention strategies to increase MHSU among college athletes.

The systematic review presented here poses a few noteworthy limitations.First,the literature search was limited mostly to published articles pertaining to U.S.collegiate athletes and approaches to mental health care vary widely from country to country.Secondly,this systematic review,while conducted in a rigorous manner,is not a meta-analysis.A relatively small number of studies were assessed and,due to the variant nature of how study researchers defined and measured MHSU,the effect of an individual facilitator or barrier in predicting MHSU could not be quantified.The studies included in this systematic review were all cross-sectional in nature,further limiting causal analysis related to MHSU.Finally,only studies concerning collegiate athletes,as well as key stakeholders who influence these athletes were included in this review.A more liberal inclusion criterion concerning study sample characteristics was employed:studies pertaining to all levels of collegiate athletics play,from D-I to junior college were included.However,comparisons across these various NCAA groups with regard to MHSU could not be made due to a small number of studies in each group.

5.Conclusion

Twenty-one articles concerning 19 unique studies on collegiate athletes’MHSU were systematically reviewed and analyzed.Study findings shed light on the need for further resources dedicated to awareness and expansion of mental health services geared toward serving the collegiate athlete.NCAA athletes not only face difficulties surrounding the transition to adulthood and college studies,but the pressure to remain in peak physical and mental condition to their athletic performance.This review demonstrates the necessity for further,more rigorous research into collegiate athletes’MHSU that employs consistent conceptualizations of mental health services utilization,valid and reliable measurement tools,and improved sample quality.Both the athlete and the culture surrounding the athlete could facilitate or hamper an athlete’s use of sport psychology and related mental health services.Socioecologically,the norms surrounding MHSU must evolve and stakeholders,specifically coaches and administrators called on to view “success”of sport psychology more dynamically.Continued research efforts are needed through deepened partnerships with the NCAA,athletic administrators,coaches,and other stakeholders to further change the norms surrounding collegiate athletes’MHSU,and ultimately,to improve mental health and well-being of the 460,000+athletes engaged in NCAA athletics.

Authors’contributions

JY conceived of the study;JJM derived article summary tables,collected and analyzed the articles,and drafted the initial manuscript;KAC collected and analyzed the articles.All authors provided manuscript draft content and completed numerous revisions.All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript,and agree with the order of presentation of the authors.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

1.Neyer M.Advising and counseling student athletes.New directions for student services2001;93:47-53.

2.Sudano LE,Collins G,Miles CM.Reducing barriers to mental health care for student-athletes:an integrated care model.FamSyst Health2017;35:77-84.

3.Brown GT,Hailine B,Kroshus E,Wilfert M,editors.Mind,body and sport:understanding and supporting student-athlete mental wellness.Indianapolis,IN:National Collegiate Athletic Association;2014.

4.Bratland-Sanda S,Sundgot-Borgen J.Eating disorders in athletes:overview of prevalence,risk factors and recommendations for prevention and treatment.Eur J Sport Sci2013;13:499-508.

5.McLester CN,Hardin R,Hoppe S.Susceptibility to eating disorders among collegiate female student-athletes.J Athl Train2014;49:406-10.

6.Barry AE,Howell SM,Riplinger A,Piazza-Gardner AK.Alcohol use among college athletes:do intercollegiate,club,or intramural student athletes drink differently?Subst Use Misuse2015;50:302-7.

7.Huang JH,Jacobs DF,Derevensky JL.Sexual risk-taking behaviors,gambling,and heavy drinking among U.S.College athletes.Arch Sex Behav2010;39:706-13.

8.National Collegiate Athletic Association Sport Science Institute.Mental health best practices:inter-association consensus document:best practices for understanding and supporting student-athlete mental wellness.Indianapolis,IN:National Collegiate Athletic Association;2016.

9.Jeanes R,Magee J,O’Connor J.Through coaching:examining a socio-ecological approach to sports coaching.In:Wattchow B,Jeanes R,Alfrey L,Brown T,Cutter-Mackenzie A,O’Connor J,editors.The sociological educator:A 21st century renewal of physical,health,environment,and outdoor education.New York,NY:Springer;2013.

10.Register-Mihalik J,Linnan LA,Marshall SW,McLeod TVC,Mueller FO,Guskiewicz KM.Using theory to understand high school aged athletes’intentions to report sport-related concussion:implications for concussion education initiatives.Brain Inj2013;27:878-86.

11.Dahlberg LL,Krug EG.Violence:a global public health problem.Cien Saude Colet2006;11:1163-78.

12.Reis S,Morris G,Fleming LE,Beck S,Taylor T,White M,et al.Integrating health and environmental impact analysis.Public Health2015;129:1383-9.

13.Eime RM,Young JA,Harvey JT,Charity MJ,Payne WR.A systematic review of the psychological and social benefits of participation in sport for children and adolescents:informing development of a conceptual model of health through sport.Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act2013;10:1-21.

14.Armstrong S,Oomen-Early J.Social connectedness,self-esteem,and depression symptomatology among collegiate athletes versus nonathletes.J Am Coll Health2009;57:521-6.

15.Morgan WP.Psychological outcomes of physical activity.In:Maughan RJ,editor.Basic and applied sciences for sports medicine.Boston,MA:Butterworth-Heinemann;1999.

16.Eisenberg D,Golberstein E,Gollust SE.Help-seeking and access to mental health care in a university student population.Med Care2007;45:594-601.

17.Hunt J,Eisenberg D.Mental health problems and help-seeking behavior among college students.J Adolesc Health2010;46:3-10.

18.Yang J,Peek-Asa C,Corlette JD,Cheng G,Foster DT,Albright J.Prevalence of and risk factors associated with symptoms of depression in competitive collegiate student athletes.Clin J Sport Med2007;17:481-7.

19.Green LW,Richard L,Potvin L.Ecological foundations of health promotion.Am J Health Promot1996;10:270-81.

20.Neighbors C,Walters ST,Lee CM,Vader AM,Vehige T,Szigethy T,et al.Event-specific prevention:addressing college student drinking during known windows of risk.Addict Behav2007;32:2667-80.

21.Stokols D.Translating social ecological theory into guidelines for community health promotion.Am J Health Promot1996;10:282-98.

22.Stokols D,Allen J,Bellingham RL.The social ecology of health promotion:implications for research and practice.Am J Health Promot1996;10:247-51.

23.Williams Jr RD,Perko MA,Usdan SL,Leeper JD,Belcher D,Leaver-Dunn DD.Influences on alcohol use among NCAA athletes:application of the Social Ecology Model.Am J Health Stud2008;23:151-9.

24.Watson JC.Overcoming the challenges of counseling college student athletes.ERIC/CASS digest.ERIC Clearing House on Counseling and Student Services;No.EDO-CG-03-01.2003.

25.Galli N,Petrie TA,Greenleaf C,Reel JJ,Carter JE.Personality and psychological correlates of eating disorder symptoms among male collegiate athletes.Eat Behav2014;15:615-8.

26.Neal TL,Diamond AB,Goldman S,Klossner D,Morse ED,Pajak DE,et al.Inter-association recommendations for developing a plan to recognize and refer student-athletes with psychological concerns at the collegiate level:an executive summary of a consensus statement.J Athl Train2013;48:716-20.

27.Rao A,Asif IM,Drezner JA,Toresdahl BG,Harmon KG.Suicide in national collegiate athletic association(NCAA)athletes:a 9-year analysis of the NCAA resolutions database.Sports Health2015;7:452-7.

28.Wolanin A,Gross M,Hong E.Depression in athletes:prevalence and risk factors.Curr Sports Med Rep2015;14:56-60.

29.Connole IJ,Watson JC,Shannon VR,Wrisberg C,Etzel E,Schimmel C.NCAA athletic administrators’preferred characteristics for sport psychology positions:a consumer market analysis.Sport Psychol2014;28:406-17.

30.Wilson KA,Gilbert J,Gilbert WD,Sailor SR.College athletic directors’perceptions of sport psychology consulting.Sport Psychol2009;23:405-24.

31.Wrisberg C,Withycombe JL,Simpson D,Loberg LA,Reed A.NCAA Division-I:administrators’perceptions of the benefits of sport psychology services and possible roles for a consultant.Sport Psychol2012;26:16-28.

32.American Psychological Association.Sport psychology.Available at:http://www.apa.org/ed/graduate/specialize/sports.aspx; 2013 [accessed 30.06.2017].

33.Association for Applied Sports Psychology.About certified consultants.Available at:http://www.appliedsportpsych.org/certified-consultants;2013[accessed 30.06.2017].

34.Reese LMS,Pittsinger R,Yang JZ.Effectiveness of psychological intervention following sport injury.J Sport Health Sci2012;1:71-9.

35.Lochbaum M, Gottardy J. A meta-analytic review of the approach-avoidance achievement goals and performance relationships in the sport psychology literature.J Sport Health Sci2015;4:164-73.

36.Burnsed B.NCAA Mental Health Task Force holds first meeting.National Collegiate Athletic Association.Available at:http://www.ncaa.org/about/resources/media-center/news/ncaa-mental-health-task-forceholds- first-meeting;2013[accessed 27.07.2016].

37.Ferrari AJ,Charlson FJ,Norman RE,Patten SB,Freedman G,Murray CJ,et al.Burden of depressive disorders by country,sex,age,and year:findings from the global burden of disease study 2010.PLoS Med2013;10:e1001547.doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1001547

38.Drake RE,Latimer E.Lessons learned in developing community mental health care in North America.World Psychiatry2012;11:47-51.

39.Turrisi R,Mastroleo NR,Mallett KA,Larimer ME,Kilmer JR.Examination of the mediational influences of peer norms,environmental influences,and parent communications on heavy drinking in athletes and nonathletes.Psychol Addict Behav2007;21:453-61.

40.Oishi S,Graham J.Social ecology:lost and found in psychological science.Perspect Psychol Sci2010;5:356-77.

41.Arthur-Cameselle JN,Baltzell A.Learning from collegiate athletes who have recovered from eating disorders:advice to coaches,parents,and other athletes with eating disorders.J Appl Sport Psychol2012;24:1-9.

42.Martin SB.High school and college athletes’attitudes toward sport psychology consulting.J Appl Sport Psychol2005;17:127-39.

43.Watson JC.Student-athletes and counseling:factors influencing the decision to seek counseling services.Coll Stud J2006;40:35-42.

44.Clement D,Granquist MD,Arvinen-Barrow MM.Psychosocial aspects of athletic injuries asperceived by athletic trainers.JAthlTrain2013;48:512-21.

45.Zakrajsek RA,Martin SB,Wrisberg CA.National Collegiate Athletic Association Division I:certified athletic trainers’perceptions of the benefits of sport psychology services.J Athl Train2016;51:398-405.

46.Zakrajsek RA,Martin SB,Wrisberg CA.Sport psychology services in performance settings:NCAA DI certified athletic trainers’perceptions.Sport Exerc Perform Psychol2015;4:280-92.

47.Lopez RL,Levy JJ.Student athletes’perceived barriers to and preferences for seeking counseling.J Coll Couns2013;16:19-31.

48.Lubker JR,Visek AJ,Watson JC,Singpurwalla D.Athletes’preferred characteristics and qualifications of sport psychology practitioners:a consumer market analysis.J Appl Sport Psychol2012;24:465-80.

49.Wrisberg C,Simpson D,Loberg LA,Withycombe JL,Reed A.NCAA Division-I:student-athletes’receptivity to mental skills training by sport psychology consultants.Sport Psychol2009;23:470-86.

50.Wrisberg CA,Loberg LA,Simpson D,Withycombe JL,Reed A.An exploratory investigation of NCAA Division-I:coaches’support of sport psychology consultants and willingness to seek mental training services.Sport Psychol2010;24:489-503.

51.Zakrajsek RA,Steinfeldt JA,Bodey KJ,Martin SB,Zizzi SJ.NCAA Division I:coaches’perceptions and preferred use of sport psychology services:a qualitative perspective.Sport Psychol2013;27:258-68.

52.Zakrajsek RA,Zizzi SJ.Factors Influencing track and swimming coaches’intentions to use sport psychology services.Athletic Insight2007;9:1-21.

53.O’Connor C,Grappendorf H,Burton L,Harmon SM,Henderson AC,Peel J.National Collegiate Athletic Association Division I:football players’perceptions of women in the athletic training room using a role congruity framework.J Athl Train2010;45:386-91.

54.Sherman RT,Thompson RA,DeHass D,Wilfert M.NCAA coaches survey:the role of the coach in identifying and managing athletes with disordered eating.Eat Disord2005;13:447-66.

55.Steinfeldt JA,Steinfeldt MC.Profile of masculine norms and help-seeking stigma in college football.Sport Exerc Perform Psychol2012;1:58-71.

56.Steinfeldt JA,Steinfeldt MC,England B,Speight QL.Gender role conflict and stigma toward help-seeking among college football players.Psychol Men Masc2009;10:261-72.

57.Watson JC.College student-athletes’attitudes toward help-seeking behavior and expectations of counseling services.J Coll Stud Dev2005;46:442-9.

58.Barnard JD.Student-athletes’perceptions of mental illness and attitudes toward help-seeking.J College Stud Psychother2016;30:161-75.

59.Martin SB,Kellmann M,Lavallee D,Page SJ.Development and psychometric evaluation of the sport psychology attitudes—revised form:a multiple group investigation.Sport Psychol2002;16:272-90.

60.Fischer EH, Turner JLB.Orientations to seeking professional help—development and research utility of an attitude scale.J Consult Clin Psychol1970;35:79-90.

61.Tinsley HEA,Brown MT,Destaubin TM,Lucek J.Relation between expectancies for a helping relationship and tendency to seek help from a campus help provider.J Consult Clin Psychol1984;31:149-60.

62.Byrd DR,McKinney KJ.Individual,interpersonal,and institutional level factors associated with the mental health of college students.J Am Coll Health2012;60:185-93.

63.Raab S,Wolfe BD,Gould TE,Piland SG.Characterizations of a quality certified athletic trainer.J Athl Train2011;46:672-9.

64.Yang J,Peek-Asa C,Lowe JB,Heiden E,Foster DT.Social support patterns of collegiate athletes before and after injury.J Athl Train2010;45:372-9.

65.Eisenberg D,Downs MF,Golberstein E,Zivin K.Stigma and help seeking for mental health among college students.Med Care Res Rev2009;66:522-41.

66.Link BG.Understanding labeling effects in the area of mental disorders:an assessment of the effects of expectations of rejection.Am Social Rev1987;52:96-112.

67.Martin JK,Pescosolido BA,Tuch SA.Of fear and loathing:the role of“disturbing behavior”,labels,and causal attributions in shaping public attitudes toward people with mental illness.J Health Soc Behav2000;41:208-23.

68.Brewer BW,Cornelius AS.Norms and factorial invariance of the Athletic Identity Measurement Scale.Acad Athl J2001;15:103-13.

69.Givens JL,Tjia J.Depressed medical students’use of mental health services and barriers to use.Acad Med2002;77:918-21.

70.Smith DM.In their own voices:attitudes about mental health utilization by African American females at a predominantly White institution.Knoxville,TE:University of Tennessee—Knoxville;2004.[Dissertation].

71.Drummond JL,Hostetter K,Laguna PL,Gillentine A,Del Rossi G.Self-reported comfort of collegiate athletes with injury and condition care by same-sex and opposite-sex athletic trainers.J Athl Train2007;42:106-12.

72.O’Neill JM,Helm B,Gable R,David L,Wrightsman L.Gender Role Conflict Scale(GRCS):college men’s fears of femininity.Sex Roles1986;14:335-50.

73.Komiya N,Good GE,Sherrod NB.Emotional openness as a predictor of college students’attitudes toward seeking professional psychological help.J Couns Psychol2000;47:138-43.

74.Parent MC,Moradi B.Confirmatory factor analysis of the Conformity to Masculine Norms Inventory and development of the Conformity to Masculine Norms Inventory.Psych Men Mascul2009;10:175-89.

75.Vogel DL,Wade NG,Haake S.Measuring the self-stigma associated with seeking psychological help.J Couns Psychol2006;53:325-37.

76.Martin SB,Akers A,Jackson AW,Wrisberg CA,Nelson L,Leslie PJ,et al.Male and female athletes’and nonathletes’expectations about sport psychology consulting.J Appl Sport Psychol2001;13:18-39.

77.Zizzi SJ,Perna FM.Integrating web pages and e-mail into sport psychology consultations.Sport Psychol2002;16:416-31.

78.Brewer BW,Van Raalte JL,Linder DE.Role of the sport psychologist in treating injured athletes:a survey of sports medicine providers.J Appl Sport Psychol1991;3:183-90.

79.Wiese DM,Weiss MR,Yukelson DP.Sport psychology in the training room:a survey of athletic trainers.Sport Psychol1991;5:15-24.

80.Martin SB,Wrisberg CA,Beitel PA,Lounsbury J.NCAA Division I:athletes’attitudes toward seeking sport psychology consultation:the development of an objective instrument.Sport Psychol1997;11:201-18.

Journal of Sport and Health Science2018年1期

Journal of Sport and Health Science2018年1期

- Journal of Sport and Health Science的其它文章

- Research highlights from the Status report for step it up!The surgeon general’s call to action to promote walking and walkable communities

- Environments favorable to healthy lifestyles:A systematic review of initiatives in Canada

- The built environment correlates of objectively measured physical activity in Norwegian adults:A cross-sectional study

- The association of various social capital indicators and physical activity participation among Turkish adolescents

- Feasibility of using pedometers in a state-based surveillance system:2014 Arizona Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System

- Matched or nonmatched interventions based on the transtheoretical model to promote physical activity.A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials