The longitudinal effect of parental support during adolescence on the trajectory of sport participation from adolescence through young adulthood

Chung Gun Lee,Seiyeong Prk,Seunghyun Yoo*

aDepartment of Physical Education,Seoul National University,Seoul 08826,Republic of Korea

bGraduate School of Public Health,Seoul National University,Seoul 08826,Republic of Korea

1.Introduction

Considerable evidence suggests that regular physical activity(PA)can prevent various kinds of chronic diseases,such as diabetes,stroke,heart disease,and osteoporosis.1-4Many studies have also shown that physical inactivity or low levels of PA can cause dramatic increases in the rate of all-cause mortality.5In addition,performing recommended levels of PA has been shown to relieve stress,depression,and anxiety.6-8Despite the clear advantages of regular PA,only51%of adults(aged18or older)were performing recommended levels of PA in the US.9One efficient way to increase PA is through sport participation because participation in sport activities inherently includes many enjoyable aspects,such as social interaction,competition,personal challenge,and goal achievement.Previous studies have identified that some of the reasons for participating in sports were enjoyment, fitness,and social interaction.10,11Sport participation has also been shown to improve self-esteem,reduce the risk for obesity,improve body image,and increase muscle mass.12,13Because participation in sport activities invariably involves PA, it is important to understand the factors that influence sport participation behavior.

General social support (not exercise-specific social support) is one of the important potential factors that may influence PA-related behaviors (e.g.,exercise,outdoor play,sport participation)and can be broadly defined as love,caring,and assistance provided by others.14Higher levels of general social support have almost always been associated with lower mortality and morbidity.15,16Furthermore,affective support was found to be more consistently and strongly associated with well-being and good health compared with other types of general social support.17,18It is possible that part of this association is attributable to the relationship between general social support and PA-related behavior.For example,general social support has been shown to play an important role in the maintenance of mental well-being,which in turn might motivate self-care behaviors,such as exercise and sport participation,in individuals.19-21High levels of general social support might also increase selfesteem,which can potentially help individuals adopt healthy behaviors and avoid unhealthy lifestyle behaviors,such as sedentariness.22-28Therefore,it is important to consider psychological health and self-esteem as potential mediators or moderators when examining the relationship between general social support and PA-related behaviors.

Although some plausible mechanisms in the relationship between general social support and PA-related behaviors have been suggested,not many studies have investigated this relationship.In the 2003 Health Survey for England,lack of general social support was associated with lower levels of PA.29Higher emotional and instrumental social support(not exercise-specific social support)was positively associated with higher levels of PA.30In a longitudinal study,initially sedentary participants became physically active if they met often with their family.31In another longitudinal study,both emotional and practical support(not exercise-specific social support)were shown to help people maintain the recommended level of PA.32In the 1990 Ontario Health Survey,social quantity(number of close friends and number of family members)and social frequency(frequency of meeting family members and close friends)were positively associated with PA.33However,most of these studies did not consider the possibility of reverse causation,as the data used by these studies were mostly cross-sectional,29,30,33and none of these studies considered both depression and self-esteem as potential mediators of the relationship between general social support and PA-related behaviors.

This study attempts to examine the effect of general social support during adolescence on sport participation from adolescence through young adulthood.This study focuses on parental support rather than other potential sources of general social support.Although peers have an important social influence on the mental well-being of adolescents,34previous evidence suggests that parental support is more strongly related to wellbeing in adolescents compared with peer support.35,36Parental support may therefore be considered as a key source of general social support for adolescents.It is unclear,however,whether people who have a lack of general social support early in life remain at an increased risk for physically inactive lifestyle later in life.According to the concept of the life course trajectory,37different points in the life course of an individual are closely connected with one another.Significant conditions and events at one point in an individual’s life course may play an important role in shaping the course of conditions and events experienced in subsequent years.If this is true,it will be necessary to find out the mechanisms underlying the effect of poor general social support early in life on the trajectory of PA-related behaviors later in life.

The main purpose of this study was to investigate the longitudinal effect of parental support during adolescence on the trajectory of sport participation from adolescence through young adulthood.We examined gender differences in the longitudinal relationship between parental support and sport participation because female adolescents may value relational closeness to a different degree or in a different way compared with male adolescents,38and previous studies have shown that male adolescents engage in higher levels of PA-related behaviors than do female adolescents.39-41We also considered depression and self-esteem as mediators of the longitudinal relationship between parental support and sport participation as previous studies emphasized the importance of psychological health and self-esteem as potential mediators of this relationship.19-28

2.Methods

2.1.Data

The data used in this study came from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health(Add Health).It is a 4-wave longitudinal study that followed up a nationally representative sample of middle and high school students(7th through 12th grade)in the US.Every high school in the US that included more than 30 enrollees and 11th grade was included in the primary sampling frame.These schools were stratified by urbanicity,region,school type,size,and ethnic mix.Using systematic random sampling,80 high schools were selected.More than 70%of these schools were recruited.Middle schools that sent graduates to already recruited high schools and included 7th grade were also recruited.A total of 134 middle and high schools were included in the final sample.In each school,students were stratified by grade and gender,and then chosen randomly from official school rosters.In 1995,the Wave 1 in-home interview was conducted from April to December.Seventy-nine percent of the selected students completed interviews.The Wave 2 interview was conducted approximately 1 year later(12%dropouts from Wave 1).The Wave 3 interview was conducted approximately 6 years after the Wave 1 interview(23%dropouts from Wave2).The Wave 4 interview was conducted between 2007 and 2008(20%dropouts from Wave 3).Additional information on the Add Health data is reported elsewhere.42This study used Waves 1-4 public-use datasets(n=6504).When properly weighted,the Add Health public-use datasets provide a nationally representative sample of U.S.middle and high school students.

2.2.Measures

Sport participation at each wave was assessed by asking participants how many times they participated in an active sport,such as baseball,basketball,soccer,swimming,or football during the past week.Because sport participation at Waves 3 and 4 was assessed by asking 2 questions,one about team sport participation and the other about individual sport participation,the number of times the participants joined individual and team sports was added to create the total number of participation in sport.Participants who participated in sports 5 or more times per week were considered active participators.Parental support at Wave 1 is the sum of the responses to 5 items,namely how close respondents feel to their resident(biological,adoptive,step,or foster)mother or father(1=not at allto 5=very much),how much they think their mother or father cares about them(1=not at allto 5=very much),whether their mother or father is warm and loving(1=strongly disagreeto 5=strongly agree),whether they are satisfied with communication with their mother or father(1=strongly disagreeto 5=strongly agree),and whether they are satisfied,overall,with their relationship with their mother or father(1=strongly disagreeto 5=strongly agree).The choice of these items is based on prior studies of parental support with the Add Health data.43,44The α reliability of paternal support and maternal support is 0.88 and 0.85,respectively.If information about maternal support is missing,the measure of paternal support is used to indicate parental support.Likewise,if information about paternal support is not available,the maternal support sum is used to indicate parental support.In cases where both maternal and paternal support measures are available,the arithmetic mean of these items is used to indicate parental support at Wave 1.This method of assessing support substantially reduces the amount of missing data associated with the parent-specific measures.

A shorter version of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression Scale was used to assess participants’depressive symptoms at Wave 1.45,46Each item was scored from 0 to 3.Several items were reverse-coded so that a higher score means a higher level of depressive symptoms.The depression scale score was summed to indicate depressive symptoms at Wave 1(Cronbach’s α =0.77).Four items were used to assess selfesteem at Wave 147(Cronbach’s α =0.72):“You felt that you were just as good as other people”,“You have a lot of good qualities”, “You have a lot to be proud of”,and “You like yourself just the way you are”.The responses to the first item were 1=never or rarely,2=sometimes,3=a lot of the time,and 4=most of the time or all of the time.A 5-point Likert scale(1=strongly disagreeto 5=strongly agree)was used to assess the last 3 items.After standardizing each response,the arithmetic mean of the 4 items was computed.Additional covariates were race and ethnicity(non-Hispanic white,non-Hispanic black,Hispanic,and others)and gender(male and female).

2.3.Statistical analysis

A series of multilevel logistic regression models were used to examine the effect of parental support at Wave 1 on the trajectory of sport participation from Wave 1 to Wave 4.48The wave was used as the time scale(1995=Wave 1,1997=Wave 2,2002=Wave 3,and 2009=Wave 4)and was centered at Wave 1 to accommodate interpretation of results(i.e.,capturing the level of average sport participation among participants at Wave 1).Intraclass correlation coefficient(ICC)was computed from the model where no predictor was included(unconditional means model)to find out the proportion of total outcome variation between different individuals.Unconditional growth model for sport participation(Model 1)was constructed to examine whether within-person variation in the outcome was significantly related to linear or quadratic time. Conditional growth models for sport participation(Models 2-5)were then constructed to investigate the effects of parental support at Wave 1 on the trajectory of sport participation from Wave 1 to Wave 4 after controlling for individual-level variables(i.e.,sport participation at Wave 1,race and ethnicity,depression,and self-esteem)in a sequential manner.Model 2 is the sport participation at Wave 1-and race and ethnicity-controlled growth model.Model 3 is the sport participation at Wave 1-,race and ethnicity-,and depression controlled growth model.Model 4 is the sport participation at Wave 1-,race and ethnicity-,and self-esteem-controlled growth model.In the final model(Model 5),depression was introduced into Model 4 to assess the effect of parental support at Wave 1 on the trajectory of sport participation from Wave 1 to Wave 4 above and beyond all other individual-level variables.We performed all the analyses separately by gender.All the analyses described above were performed using HLM Version 6.08(Scientific Software International,Lincolnwood,IL,USA).

3.Results

3.1.Descriptive statistics

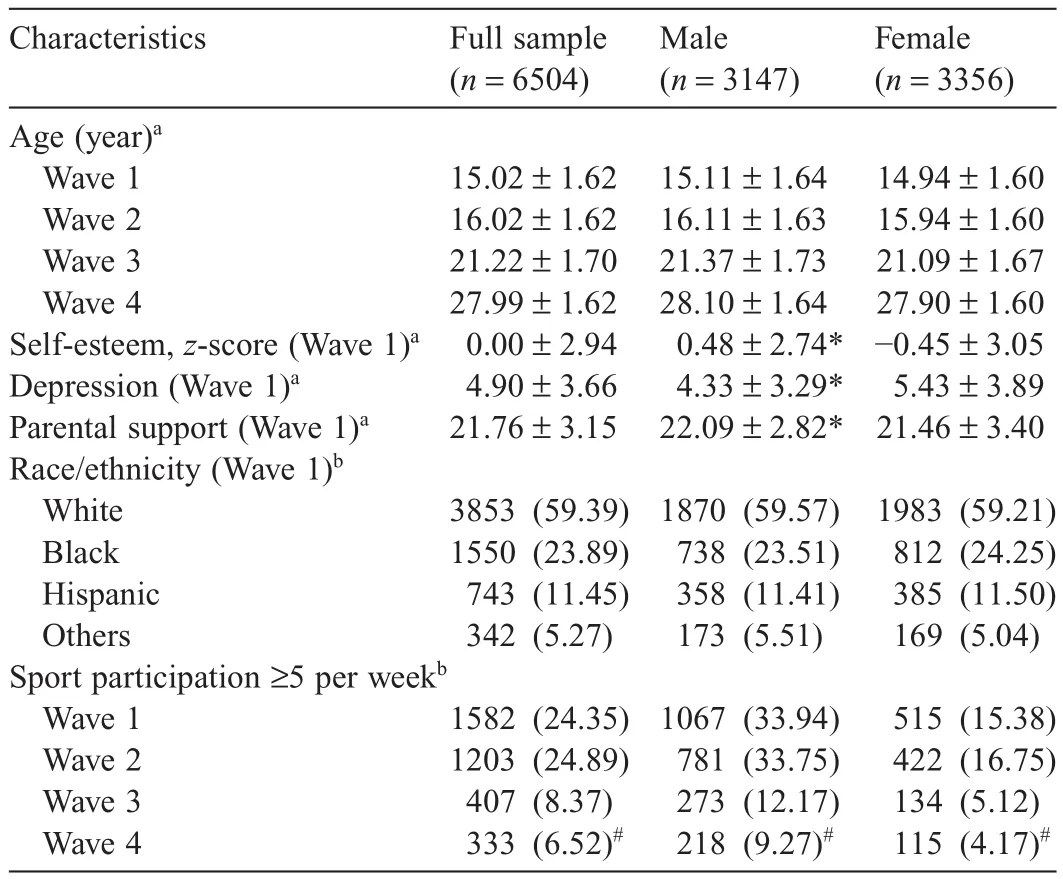

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the participants at each wave.The mean age at each wave was similar between male and female participants.Both the mean of self-esteemz-score at Wave 1 and the mean of parental support at Wave 1 were higher in male than female adolescents(p<0.001).On the contrary,the average depression score of male adolescents was lower than that of female adolescents at Wave 1(p<0.001).For bothgenders,there was a decrease in the proportion of sport participation as participants aged from Wave 1(mean age of 15 years)to Wave 4(mean age of 28 years)(p<0.001).

Table 1Descriptive characteristics of participants.

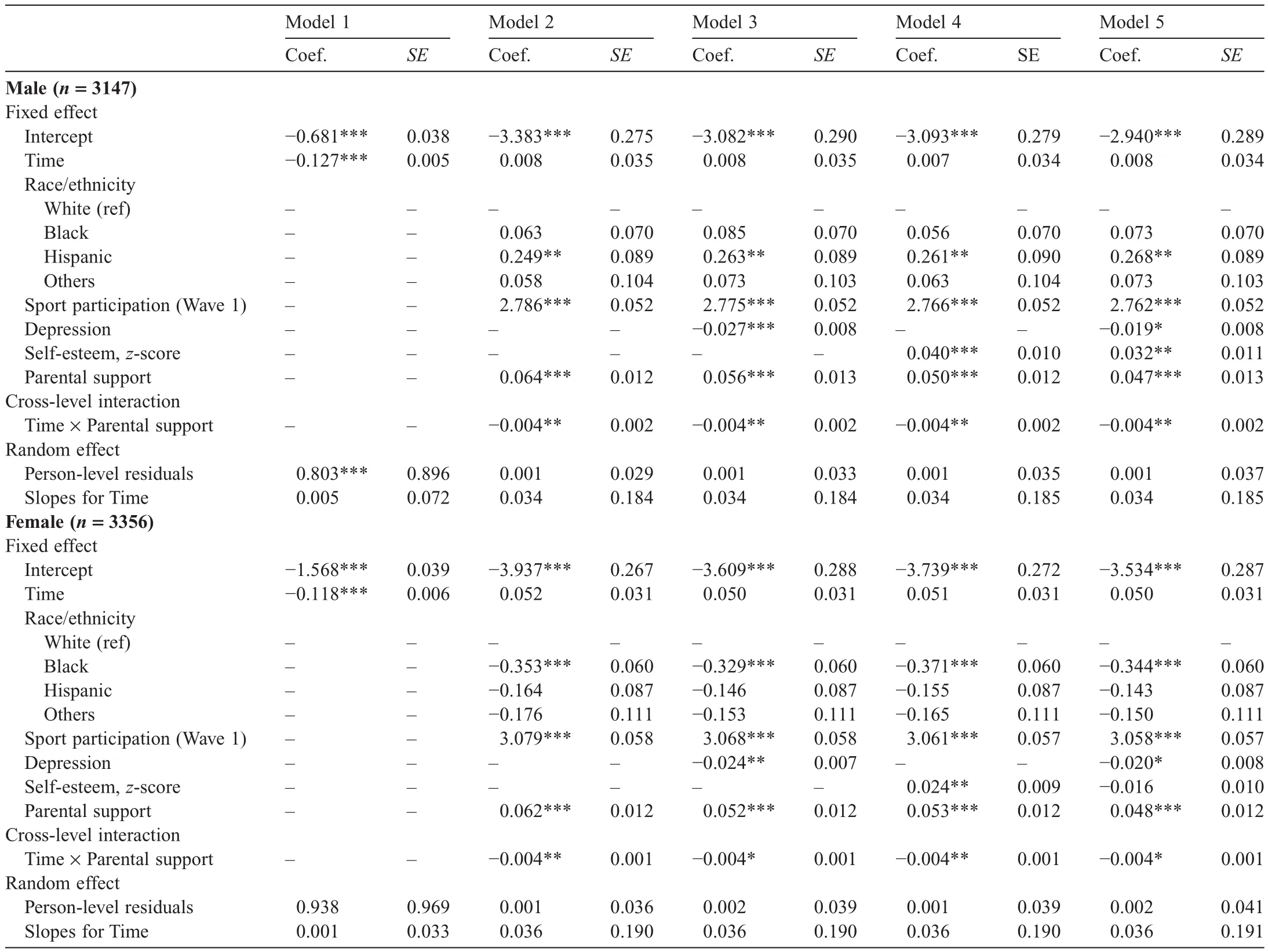

3.2.Trajectory of sport participation

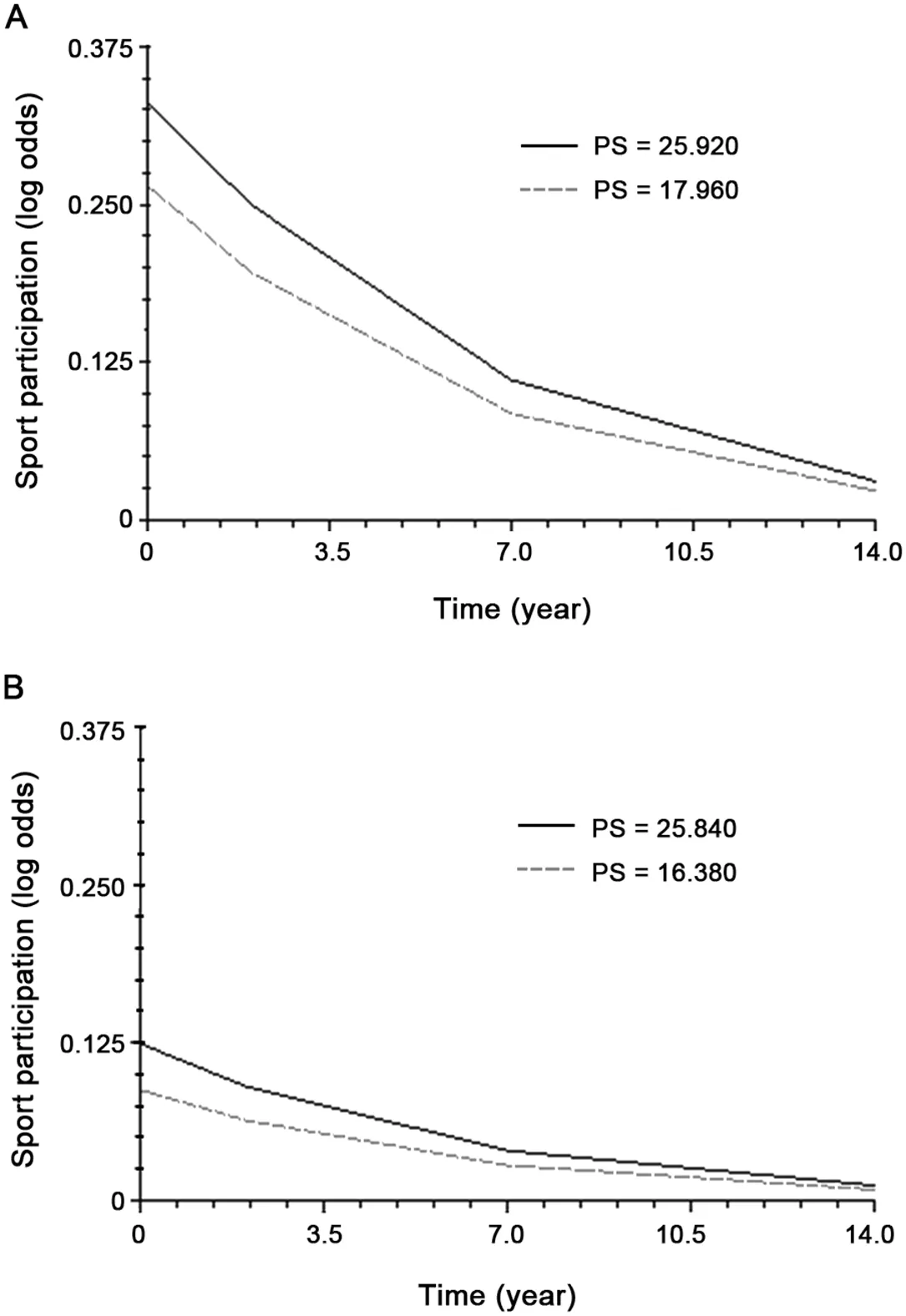

Table 2 shows the results of the series of multilevel logistic regression models that examined the trajectory of participants’sport participation from adolescence through young adulthood.Among the male participants,the population average probability of sport participation was 0.225,that is,e-1.239/(1+e-1.239)=22.5%(95%confidence interval:21.4%-23.5%).In the null model,the person-level residual variance was 0.55.Thus,the ICC was 0.14=0.55/(0.55+3.29),49indicating that 14%of variance in male participants’sport participation was explained by the differences between individuals.Therefore,the multilevel approach was warranted.In unconditional growth model(Model 1),only linear time was significant,indicating a downward linear trend in sport participation with time(p<0.001).In Model 2,parental support atWave 1 was significantly associated with sport participation at Wave 1 after controlling for sport participation at Wave 1 and race and ethnicity(p<0.001).A significant crosslevel interaction between time and parental support indicates that the positive effect of parental support at Wave 1 on sport participation becomes weaker as time passes(p<0.01).Parental support at Wave 1 was a significant predictor for sport participation at Waves 1,2,and 3(p<0.001)but not for sport participation at Wave 4(not shown in Table 2).In Model 3,depression at Wave 1 was negatively associated with sport participation at Wave 1(p<0.001).In Model 4,self-esteem at Wave 1 was positively associated with sport participation at Wave 1(p<0.001).In the final model(Model 5),parental support atbaseline(Wave 1)was a significant predictor for Wave 1 sport participation(p<0.001)even after controlling for all other individual-level variables,indicating that parental support during adolescence has an independent effect on adolescent sport participation over and above the effects of depression and selfesteem.However,as shown in Fig.1A,a significant effect of parental support at Wave 1 on sport participation in early young male adulthood(Wave 3)becomes insignificant when adjusting for self-esteem and depression(not shown in Table 2).

Table 2Multilevel logistic regression models examining trajectory of participants’sport participation from adolescence through young adulthood.

Fig.1.The trajectory of sport participation from adolescence through young adulthood by parental support among male(A)and female(B)participants.The solid and dotted lines indicate averaged upper and lower quartiles of parental support,respectively.PS=parental support.

The population average probability of sport participation among female participants was 0.108,that is,e-2.111/(1+e-2.111)=10.8%(95%confidence interval:10.1%-11.6%).The personlevel residual variance was 0.76 in the null model.Thus,the ICC was 0.19=0.76/(0.76+3.29).49Because 19%of variance in female participants’sport participation was explained by the differences between individuals,the multilevel approach was warranted.The results of Models 1-5 among female participants were very similar to those among the male participants.However,as shown in Fig.1B,parental support at Wave 1 was a significant predictor for sport participation at Waves 1,2,and 3(p<0.01)even after depression and self-esteem were introduced into the model(not shown in Table 2).That is to say,unlike male participants,parental support during adolescence has an independent effect on sport participation from adolescence(Wave 1)through early young adulthood(Wave 3)over and above the effects of depression and self-esteem in female participants.

4.Discussion

This study is the first study that investigated the effect of parental support(not exercise-specific parental support)during adolescence on the trajectory of sport participation from adolescence to young adulthood using nationally representative data from the Add Health.In addition,our study also examined whether self-esteem and depression mediated the effect of parental support on sport participation from adolescence through young adulthood.Overall,the results of our study showed that parental support during adolescence had an independent effect on sport participation from adolescence(Wave 1)through early young adulthood(Wave 3)over and above self-esteem and depression in female participants.However,unlike female participants,self-esteem and depression mediated the effect of parental support in adolescence on sport participation during early young adulthood(Wave 3)in male participants.

Consistent with previous findings,29-33the results of our study showed that adolescents who think they receive higher levels of general social support from their parents are more likely to participate in recommended levels of sporting activities.Low levels of general social support have been repeatedly associated with increased morbidity and mortality.15,16It is possible that a significant part of this association is attributable to the relationship between general social support and PA-related behaviors,such as sport participation.The findings from our study extend previous findings on the association between general social support and PA-related behaviors by suggesting that this association is also evident in adolescence.

Another finding of note is that the effect of parental support during adolescence on participants’sport participation lasted until they became young adults.Most of the current studies on the effects of early parental support focus on comparatively immediate outcomes.For example,early parental support has been shown to affect problem behaviors among adolescents,50as well as their mental and physical health.51Because examining the long-term effects of early parental support is also important,several previous studies have shown that early parental support is linked to mental and physical health during young adulthood and midlife.52-55The results of our study add to the previous body of results on the association between early parental support and young adult health by suggesting that sport participation may act as an important mediator or moderator in this association.

Although several mechanisms explaining the association between general social support and PA-related behaviors have been proposed,56not many studies have examined the mediators of this association.32,57For example,general social support plays an important role in the maintenance of psychological well-being,which in turn motivates self-care behaviors,such as sport participation and exercise,in individuals.19-21High levels of general social support might also increase self-esteem,which can potentially help individuals adopt self-care behaviors and avoid unhealthy lifestyle behaviors,such as sedentariness.22-28The results of this study showed that the relationship between parental support during adolescence,which is a major source of general social support for adolescents,and sport participation during early young adulthood(Wave 3)was fully mediated by depression and self-esteem in male participants.However,the relationship between parental support in adolescence and sport participation from adolescence to young adulthood was not fully mediated by depression and self-esteem in female participants.There was a very small change after controlling for depression and self-esteem.This result is in line with Kouvonen et al.’s32study showing that the link between high levels of general social support and performing recommended levels of leisure time PA is not mediated through depression status.Kouvonen et al.’s study,however,did not consider self-esteem as a mediator between general social support and PA.Further studies are needed to investigate other potential mediators in addition to self-esteem and depression when examining the relationship between general social support and PA-related behaviors in female participants.

This study is not without some important limitations.First,this study only considered 1 source of social support.58Previous studies suggest that although parental support is the most important social influence on the health and well-being of adolescents,35,36peer support also has an important role in the lives of adolescents.34Because learning to stand alone and becoming independent from parents are the key developmental tasks during adolescence,relationships with peers become increasingly important during this period of the life course.59However,proper measurements of peer support are not included in the dataset we used.42Future studies need to consider how peer support and parental support interact with developmental trajectories of sport participation.Second,this study used a questionnaire that asked only about emotional support,which provides love and caring,as opposed to practical support,which provides tangible assistance with a goal or task.In other words,this study could not differentiate between emotional and practical support and assess how each of these can differentially influence PA-related behaviors.Third,the Add Health data did not allow the use of more specific types and amount of sport participation.For example,team sport participation could not be distinguished from individual sport participation because the measure of sport participation in the Add Health data at Waves 1 and 2 did not distinguish between team sport participation and individual sport participation.To understand more precisely the influence of parental support received during adolescence on sport participation throughout the life course,future studies need to use the measure of sport participation from various sources.Despite these limitations,the results of this study contributed to the literature by providing important information on the trajectory of sport participation in relation to parental support during adolescence using a nationally representative sample of participants transitioning from adolescence to young adulthood.

Acknowledgment

This study was supported by Seoul National University.

Authors’contributions

CGL conceived of the study,drafted the manuscript,and performed the statistical analysis;SP helped draft the manuscript and perform the statistical analysis;SY participated in study design and coordination and helped draft the manuscript.All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript,and agree with the order of presentation of the authors.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

1.Bassuk SS,Manson JE.Epidemiological evidence for the role of physical activity in reducing risk of type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease.J Appl Physiol2005;99:1193-204.

2.Kohrt WM,Bloom field SA,Little KD,Nelson ME,Yingling VR,American College of Sports Medicine.American College of Sports Medicine Position Stand:physical activity and bone health.Med Sci Sports Exerc2004;36:1985-96.

3.Sigal RJ,Kenny GP,Wasserman DH,Castaneda-Sceppa C,White RD.Physical activity/exercise and type 2 diabetes:a consensus statement from the American Diabetes Association.Diabetes Care2006;29:1433-8.

4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.Promoting better health for young people through physical activity and sports.A report to the President from the Secretary of Health and Human Services and the Secretary of Education.Silver Spring,MD:U.S.Department of Health and Human Services,U.S.Department of Education;2000.

5.Löllgen H,Böckenhoff A,Knapp G.Physical activity and all-cause mortality:an updated meta-analysis with different intensity categories.Int J Sports Med2009;30:213-24.

6.Shephard RJ.Aerobic fitness&health.Champaign,IL:Human Kinetics;1994.

7.Stephens T.Physical activity and mental health in the United States and Canada:evidence from four population surveys.Prev Med1988;17:35-47.

8.Leith LM.Foundations of exercise and mental health.Morgantown,WV:Fitness Information Technology;2010.

9.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.Behavioral risk factor surveillance system survey data.Atlanta,GA:U.S.Department of Health and Human Services,Centers for Disease Control and Prevention;2009.

10.Pepe MV,Gandee RF.Ohio senior Olympics:creating the new adult image.In:Harris W,Harris R,Harris W,editors.Physical activity,aging and sports:practice,program and policy.New York,NY:The Center for the Study of Aging;1992.p.75-82.

11.Stevenson CL.Seeking identities:towards an understanding of the athletic careers of masters swimmers.Int Rev Sociol Sport2002;37:131-46.

12.Koivula N.Sport participation:differences in motivation and actual participation due to gender typing.J Sport Behav1999;22:360-81.

13.Hines S,Groves DL.Sports competition and its influence on self-esteem development.Adolescence1989;24:861-9.

14.Cohen S,Syme SL.Issues in the study and application of social support.In:Cohen S,Syme SL,editors.Social support and health.San Francisco,CA:Academic Press;1985.p.3-22.

15.House JS,Landis KR,Umberson D.Social relationships and health.Science1988;241:540-5.

16.Berkman LF.The role of social relations in health promotion.Psychosom Med1995;57:245-54.

17.Glanz K,Rimer BK,Viswanath K.Health behavior and health education:theory,research and practice.4th ed.San Francisco,CA:Jossey-Bass;2008.

18.Thoits PA.Stress,coping,and social support processes:where are we?What next?J Health Soc Behav1995;53-79.

19.Kawachi I,Berkman LF.Social ties and mental health.J Urban Health2001;78:458-67.

20.Parker JS,Benson MJ.Parent-adolescent relations and adolescent functioning:self-esteem,substance abuse and delinquency.Adolescence2004;39:519-30.

21.Eisenberg ME,Olson RE,Neumark-Sztainer D,Story M,Bearinger LH.Correlations between family meals and psychosocial well-being among adolescents.Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med2004;158:792-6.

22.Stansfeld SA,Bosma H,Hemingway H,Marmot MG.Psychosocial work characteristics and social support as predictors of SF-36 health functioning:the Whitehall II Study.Psychosom Med1998;60:247-55.

23.Neumark-Sztainer D.Preventing the broad spectrum of weight related problems:working with parents to help teens achieve a healthy weight and positive body image.J Nutr Educ Behav2005;37(Suppl.2):S133-9.

24.Goodman E,Whitaker RC.A prospective study of the role of depression in the development and persistence of adolescent obesity.Pediatrics2002;110:497-504.

25.Nelson MC,Gordon-Larsen P.Physical activity and sedentary behavior patterns are associated with selected adolescent health risk behaviors.Pediatrics2006;117:1281-90.

26.Maccoby EE,Martin JA.Socialization in the context of the family:parent-child interaction.In:Hetherington EM,editor.Socialization,personality,and social development.New York,NY:John Wiley;1983.p.1-101.

27.Olsson GI,Nordström ML,Arinell H,von Knorring AL.Adolescent depression:social network and family climate.A case-control study.J Child Psychol Psychiatry1999;40:227-37.

28.Sargrestano LM,Paikoff RL,Holmbeck GN,Fendrich M.A longitudinal examination of familial risk factors for depression among inner-city African American adolescents.J Fam Psychol2003;17:108-20.

29.Poortinga W.Perceptions of the environment,physical activity,and obesity.Soc Sci Med2006;63:2835-46.

30.Fischer Aggarwal BA,Liao M,Mosca L.Physical activity as a potential mechanism through which social support may reduce cardiovascular disease risk.J Cardiovasc Nurs2008;23:90-6.

31.Zimmermann E,Ekholm O,Grønbaek M,Curtis T.Predictors of changes in physical activity in a prospective cohort study of the Danish adult population.Scand J Public Health2008;36:235-41.

32.Kouvonen A,De Vogli R,Stafford M,Shipley MJ,Marmot MG,Cox T,et al.Social support and the likelihood of maintaining and improving levels of physical activity:the Whitehall II Study.Eur J Public Health2012;22:514-8.

33.Spanier PA,Allison KR.General social support and physical activity:an analysis of the Ontario Health Survey.CanJPublicHealth2001;92:210-3.

34.Dornbusch SM.The sociology of adolescence.Annu Rev Sociol1989;15:233-59.

35.Helsen M,Vollebergh W,Meeus W.Social support from parents and friends and emotional problems in adolescence.J Youth Adolesc2000;29:319-35.

36.Raja SN,McGee R,Stanton WR.Perceived attachments to parents and peers and psychological well-being in adolescence.J Youth Adolesc1992;21:471-85.

37.Elder GH,George LK,Shanahan MJ.Psychosocial stress over the life course.In:Kaplan HG,editor.Psychosocial stress:perspectives on structure,theory,life course,and methods.Orlando,FL:Academic Press;1996.p.247-92.

38.Gilligan C.In a different voice:psychological theory and women’s development.Cambridge,MA:Harvard;1982.p.24-39.

39.Gustafson SL,Rhodes RE.Parental correlates of physical activity in children and early adolescents.Sports Med2006;36:79-97.

40.Trost SG,Pate RR,Ward DS,Saunders R,Riner W.Correlates of objectively measured physical activity in preadolescent youth.Am J Prev Med1999;17:120-6.

41.Raudsepp L.The relationship between socio-economic status,parental support and adolescent physical activity.Acta Paediatr2006;95:93-8.

42.Harris KM,Halpern CT,Whitsel E,Hessey J,Tabor J,Entzel P,et al.The National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health:study design.Available at:http://www.cpc.unc.edu/projects/addhealth/design;2009 [accessed 02.03.2016].

43.Cornwell B.The dynamic properties of social support:decay,growth,and staticity,and their effects on adolescent depression.SocForces2003;81:953-78.

44.Harker K.Immigration generation,assimilation,and adolescent psychological well-being.Soc Forces2001;79:969-1004.

45.Radloff LS.The CES-D scale:a self-report depression scale for research in the general public.Appl Psychol Meas1977;1:385-401.

46.Primack BA,Swanier B,Georqiopoulos AM,Land SR,Fine MJ.Association between media use in adolescence and depression in young adulthood:a longitudinal study.Arch Gen Psychiatry2009;66:181-8.

47.Resnick MD,Bearman PS,Blum RW,Bauman KE,Harris KM,Jones J,et al.Protecting adolescents from harm: findings from the National Longitudinal Study on Adolescent Health.JAMA1997;278:823-32.

48.Singer JD.Using SAS PROC MIXED to fit multilevel models,hierarchical models,and individual growth models.J Educ Behav Stat1998;23:323-55.

49.Hox JJ.Multilevel analysis:techniques and applications.Mahwah,NJ:Lawrence Erlbaum;2002.

50.Wills TA,Cleary SD.How are social support effects mediated?A test with parental support and adolescent substance use.J Pers Soc Psychol1996;71:937-52.

51.Newcomb MD,Bentler PM.Impact of adolescent drug use and social support on problems of young adults:a longitudinal study.J Abnorm Psychol1988;97:64-75.

52.Luecken LJ.Attachment and loss experiences during childhood are associated with adult hostility,depression,and social support.J Psychosom Res2000;49:85-91.

53.Richman JA,Flaherty JA.Childhood relationships,adult coping resources and depression.Soc Sci Med1986;23:709-16.

54.Enns MW,Cox BJ,Clara I.Parental bonding and adult psychopathology:results from the US National Comorbidity Survey.Psychol Med2002;32:997-1008.

55.Russek LG,Schwartz GE.Perceptions of parental caring predict health status in midlife:a 35-year follow-up of the Harvard Mastery of Stress Study.Psychosom Med1997;59:144-9.

56.Woolger C,Power TG.Parent and sport socialization:views from the achievement literature.J Sport Behav1993;16:171-89.

57.Motl RW,Dishman RK,Saunders RP,Dowda M,Pate RR.Perceptions of physical and social environment variables and self-efficacy as correlates of self-reported physical activity among adolescent girls.J Pediatr Psychol2007;32:6-12.

58.Needham BL.Reciprocal relationships between symptoms of depression and parental support during the transition from adolescence to young adulthood.J Youth Adolesc2008;37:893-905.

59.Steinberg L,Silverberg SB.The vicissitudes of autonomy in early adolescence.Child Dev1986;57:841-51.

Journal of Sport and Health Science2018年1期

Journal of Sport and Health Science2018年1期

- Journal of Sport and Health Science的其它文章

- Research highlights from the Status report for step it up!The surgeon general’s call to action to promote walking and walkable communities

- Environments favorable to healthy lifestyles:A systematic review of initiatives in Canada

- The built environment correlates of objectively measured physical activity in Norwegian adults:A cross-sectional study

- The association of various social capital indicators and physical activity participation among Turkish adolescents

- Feasibility of using pedometers in a state-based surveillance system:2014 Arizona Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System

- Matched or nonmatched interventions based on the transtheoretical model to promote physical activity.A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials