The Relationships Between Contextual Variables and Perceived Importance and Benefits of Environmental Management Accounting (EMA) Techniques

Hatem Mohamed EL-Shishini, Makarand Upadhyaya

1 Accounting Department, College of Business Administration, University of Bahrain, Zallaq, P.O. BOX 32028,Bahrain

2 Department of Management and Marketing, College of Business Administration, University of Bahrain, Zallaq, P.O.BOX 32028, Bahrain

1 Introduction

In recent years, environmental issues have emerged, and organizations are required to respond to these issues and to consider the effects of their activities on the environment. According to Xiaomei (2004), environmental issues include global warming, soil and water pollution, noise pollution, and contaminated oceans and rivers. In addition, Medley (1997) recognized that organizations have faced with increased environmental legislation and growing environmental awareness from stakeholders including consumers, bankers, investors, employees and senior managers. Schaltegger et al. (2000) suggested that shareholders are interested in financial results and may only partially interested in information relating to pollution information in physical units. On the other hand, environmental protection agencies are interested in physical units relating to pollution and waste and less interest in financial information such as the cost of pollution and waste reduction.

Traditional management accounting has been criticized on the ground that it has failed in addressing the need for providing explicit considerations of environmental issues with environmental costs normally hidden in general overhead accounts and potential environmental benefits are missed to report or even ignored (Jasch,2003, Papaspyropoulos et al., 2012). The United Nations Division for Sustainable Development (UNDSD)stated:

"Conventional management accounting systems attribute many environmental costs to general overhead accounts, with the consequence that product and production managers have no incentive to reduce environmental costs and executives are often unaware of the extent of environmental costs…. When environmental costs are allocated to overhead accounts shared by all product lines, products with low environmental costs subsidize those with high costs.This results in incorrect product pricing which reduces profitability "(United Nations Division for Sustainable Development, 2001).

Also, Burritt (2004) argued that traditional management accounting tends to neglect identification, classification, measurement, and reporting of environmental information; therefore, many organizations do not incorporate environmental aspects (i.e. environmental costs) in their decisions-making process.

Environmental management accounting (EMA) has been emerged to overcome the criticisms of traditional management accounting. Burritt et al. (2002) argued that EMA may overcome limitations of traditional management accounting by providing a better understanding and quantifying environmental related aspects for decision making.

EMA has been established over the last decades through the published work of researchers and professionals. During the 1990s, professional organizations have promoted the role of environmental accounting in the identification and allocation of environmental costs, the investigation of the alternate use of environmental waste, and supporting the company's establishment and operation of an environmental management system.Savage and Jasch (2004) presented a broad definition of EMA as the identification, collection, analysis, and use of two type of information for internal decision making: the first is the physical information on use, flows,and fates of energy, water, and materials (including waste) and the second is monetary information on environmental-related-costs, earnings, and savings. According to Xiaomei (2004) and Jasch (2011), Environmental Management Accounting (EMA) aims to bring together both financial and physical information relating to environmental impacts and performance of a business. Furthermore, Schaltegger et al. (2000) classified the two dimensions (i.e. monetary and physical ) into two sub-dimensions past-oriented and future-oriented. For monetary past-oriented includes annual environmental costs from cost accounting; however, for monetary future-oriented involves budgeting, investment appraisal, and calculating costs, savings, and benefits of projects. For physical past-oriented includes materials and energy flow and environmental performance indicators and benchmarking; however, physical future-oriented includes physical environmental budgeting and investment appraisal, and setting quantified performance targets. EMA includes: life-cycle costing, full-cost accounting, benefits assessment, and strategic planning for environmental management, and materials and energy flow accounting (Savage and Jasch, 2004; Schaltegger et al., 2012).

Previous research has focused on promoting EMA and its potential benefits (United Nations Division for Sustainable Development, 2001). Also, there are some case studies (Burritt et al., 2011, Hendro et al., 2008)in different developed countries that showed specific organization experience with EMA. There is a little attention given to the explanatory factors for EMA practice. Burritt et al. (2010) call for future research to empirically investigate the relationship between EMA use and other potential benefits. They suggest many factors that could be used in studying EMA such as legal requirements, stakeholder pressure and the attitude of organizations towards environmental issues. Furthermore, Christ and Burritt (2013) suggest replication of their study across different settings in order to determine whether the results obtained are globally applicable.

Given the small number of research relating to EMA, this research aimed to examine the contextual factors influencing EMA practices, it seems to be important to study EMA practices. Also, Bahrain is an Asian country where there is no formal information relating to EMA. Bahrain has issued Law No.7 in 1980 titled"Environmental protection" that aims to protect against all sources of pollution. Therefore, studying the im-portance attached to and the benefits derived from EMA's techniques in Bahrain is of particular importance.More specifically, this research aims to:

· Determine the accountants' perception of the importance attached to EMA techniques.

· Determine the accountants' perception of the benefits derived from EMA techniques.

· Explore contextual variables that may affect the accountants' perception of the importance attached to and the benefits derived from EMA techniques.

2 Literature review

The research relating to EMA provides cases that demonstrate many aspects of EMA. For example, Burritt and Saka (2006) examined the link between eco-efficiency measurement and EMA in Japan. They examined many case studies and the major conclusion of their study is that EMA is underutilized and there is a need for further promotion for EMA. Gale (2006) applied EMA's framework to the financial reports of a Canadian company. There was no environment account that the environmental costs are included in overhead accounts.EMA framework is centered around classifying environmental costs into four groups: (1) waste and emission treatment costs; (2) prevention and environmental management costs; (3) material purchase value of nonproduct output costs; and (4) processing costs of non-product output. The study indicates that the total environmental costs under EMA are at least twice as much as would be normally reported. Also, (Staniskis and Stasiskiene, 2006) argue that EMA is important for the environmental management decision, product and process design, cost allocation and control, capital budgeting, product pricing, and performance evaluation.Companies that use EMA as a part of an integrated management system are provided with accurate information for measurement and reporting of environmental performance. Investigating current state of EMA practices in Lithuania indicates that there are many similarities in what improvements can be suggested for environmentally concerned companies both in terms of environmental sound operation and for reporting of environmental management accounting information. In addition, Lee (2012) explores the role of environmental management accounting and, in particular, the eco-control approach for carbon management as part of the management of a firm’s supply chain. A case study of Korean automobile manufacturers aims to examine the roles and usefulness of eco-control as a means of identifying and measuring carbon performance in a production plant. The results indicate that eco-control can support alignment between a firm’s carbon management strategy and carbon performance measurement, and provides useful quantified information for corporate decision makers. Furthermore, viable mapping of carbon flow in production provides important opportunities to improve carbon performance within the supply chain.

Examining prior case studies indicates that most of the case studies have been undertaken in the different developed countries including-for example- Australia (Gale, 2006), Austria (Jasch, 2006), Korea (Lee, 2012),and Lithuania (Staniskis and Stasiskiene, 2006). There is no evidence relating to the current situation in Bahrain. Also, using a case study methodology is always criticized on the ground that it fails in generalizing the results to other organizations.

There are many studies that aimed to explain the observed practice relating to some aspects of EMA. The contingency theory of management accounting provides a basis for explaining the differences in perceptions among accountants relating to the importance attached to EMA's techniques and derived benefits from those techniques. The basic of idea of contingency theory has been demonstrated by Otley (1980). He suggests that"particular features of an appropriate accounting system will depend upon the specific circumstances in which an organization finds itself" (Otley, 1980). This implies that the contingency theory research focuses on the fit between contextual factors and aspects of an accounting system must somehow fit together for an organization to be effective. Drazin and Van de Ven (1985) identify two forms of fit relating to structural contingency theory—the selection and interaction approaches. The first examines the relationship between contextual factors and organization structure without examining whether this context-structure relationship affects performance. In contrast, the second (i.e. the interaction) seeks to explain variations in organizational performance from the interaction of organizational structure and context. Thus, only certain designs are expected to give high performance in a given context, and departures from such designs are expected to give a lower perfor-mance. Given that organizations are assumed to have varying degrees of fit, the task of the researcher is to show that a higher degree of fit between context and structure is associated with higher performance.

In terms of management accounting control systems research, the vast majority of studies have adopted the selection approach (e.g.: Chenhall, 2003; Luft and Shields, 2003) whereby characteristics of the accounting system represent the dependent variable. Accounting researchers have justified the selection approach based on the assumption that rational managers are unlikely to use accounting systems that do not assist in enhancing performance (Chenhall, 2003). Also, Christ and Burritt (2013) argued that the use of selection approach is considered as an initial stage of studying EMA. This study will use the selection approach to be consistent with prior research.

There is some studies used survey methodology in order to examine EMA at many companies (i.e. surveys)and, therefore; to be able to generalize the results. For example, (Frost and Wilmshurst, 1998) examined the environmental accounting (i.e. environmental management accounting) within Top 500 Australian companies.The results indicated that environmental information was most often incorporated into internal decisions, investment appraisal, and the budgeting system. However, the use of environmental information for performance evaluation seems limited. Recently, there are two studies (Burritt et al., 2010; Christ and Burritt, 2013)that used the contingency theory to explain aspects of EMA. Burritt et al. (2010) have undertaken a survey that examined the relationship between business strategy, process innovation, product innovation and EMA use. The results indicated that there was a positive association between process innovation and the EMA use.They also found no significant relationship between business strategy and EMA use. They have noted that the type of industry was the key driver for EMA use. Furthermore, Christ and Burritt (2013) have examined the relationship between environmental strategy, organizational size, and environmental-sensitive organization and the accountant's perception for the current and future use of EMA. Using a sample of Australian accountants, the results indicated that there was an association between, environmental strategy, organizational size,environmentally-sensitive industry, and present and future use of EMA. This study highlighted that the potential role of the contingency theory in understanding reasons that explain the adoption, use, and benefits of EMA.

3 Research hypotheses

A literature review was undertaken to identify the potential contextual factors that may influence accountants'perception of the importance and benefits derived from EMA's techniques. The following contextual factors are examined:

· Size of the Organization

· Intensity of Competition

· Type of Industry

· Cost structure

3.1 Size of the Organization

The contingency theory literature suggests that size of the organization may affect the design of the organizational structure and the use of management accounting system. Many researchers (e.g.: Ezzamel, 1990;Merchant, 1981; Williamson, 1970) argue that, as the firm’s size increases, the management accounting system tends to be more sophisticated. For example, Khandwalla (1972) indicated that organization size, as measured by sales revenue, was positively associated with the sophistication of control and information systems. Furthermore, Moores and Chenhall (1994) have found the size to be an important factor influencing the adoption of complex administrative strategy. This implies that large organizations have relatively greater access to resources to use in the introduction of more sophisticated accounting systems (i.e. EMA). Also, Christ and Burritt (2013) found that size of the organization is positively associated with accountant's perceptions of the present role and future role of EMA at the organizational level. Drawing on the above discussion, the size of the organization could explain the adoption of some EMA's techniques and accountants' perception of the importance and benefits derived from EMA's techniques. Therefore, this study considered the following hypothesizes:

H1: There is a positive association between the size of the organization and the accountants' perception of the importance of implementing EMA techniques.

H2: There is a positive association between the size of the organization and the accountants' perception of the importance of benefits derived from EMA techniques.

3.2 Intensity of Competition

Many researchers (e.g.: Khandwalla, 1972; Libby and Waterhouse, 1996; Simons, 1990) suggest that companies facing intensely competitive markets tend to adopt more sophisticated management accounting systems.Furthermore, Gordon and Miller (1976) argued that intensity of competition leads to the use of broad scope information in terms of financial and non-financial (i.e. the type of information in use). Similar results were reported by Gordon and Narayanan (1984) and (Chenhall and Morris, 1986). As indicated earlier, EMA involves financial and non-financial information; it can be argued that the intensity of competition is associated with the accountants' perception of the importance and the benefits derived from EMA techniques.Based on the above discussion and argument the following hypotheses are formulated:

H3: There is a positive association between the intensity of competition and the accountants' perception of the importance of EMA techniques.

H4: There is a positive association between the intensity of competition and the accountants' perception of the importance of benefits derived from EMA techniques.

3.3 Type of Industry

According to Abrahamson (1991), a diffusion of innovation may be clear within the same industry. He implies that organizations within the same industry type may imitate other organizations. Shields (1997) argues that the design of cost and information systems are dependent on the characteristics of industries. Therefore,the imitation may result in similar accounting systems being adopted within a specific business industry.Frost and Wilmshurst (1998) suggest that it is logical to assume that a firm within the retail industry will have different environmental management procedures than a similar counterpart firm in Chemical Industry.Also, Burritt et al. (2010) found the type of industry to be a significant predictor of EMA practice and innovation in Australia. Christ and Burritt (2013) suggest that the degree of environmental sensitivity in an industry would be positively associated with the current role and future role of EMA. The results indicated that there was an association between the present and future use of EMA and type of industry. Therefore, the following hypothesizes are tested:

H5: There is a positive association between the type of industry and the accountants' perception of the importance of EMA techniques.

H6: There is a positive association between the type of industry and the accountants' perception of the importance of benefits derived from EMA techniques.

3.4 Cost Structure

Cost management's studies focus on the proportion of direct costs and indirect costs to the total costs and their effect on the sophistication of cost systems. Cooper and Kaplan (1987) argued that firms with high indirect costs should assign these costs using a sophisticated cost system. Brierley et al. (2001) indicated that direct materials costs tend to be higher than indirect costs. This implies that indirect costs represent a relatively small portion of the total costs in some industries; therefore, it does not deserve investing in sophisticated accounting systems to allocate indirect costs. In EMA literature, many researchers (e.g.: Bennett et al., 2003;Epstein and Young, 1999; Jasch, 2003; Papaspyropoulos et al., 2012) argued that environmental costs are hidden and allocated using manufacturing overhead costs pools. The percentage of environmental costs varies across companies. According to Frost and Wilmshurst (1998), cost-benefits analysis has been undertaken for environmental issues including energy efficiency, by product use, pollution minimization, site cleanup, site contamination, and recyclable containers. This implies that the percentage of environmental costs to overhead can affect the cost-benefit analysis; therefore, it can affect the importance of EMA's techniques and the importance of benefits derived from these techniques. In other words, a low percentage of environmental costs do not warrant a special treatment and the importance of EMA's techniques is minimized.Following that cost management literature, it can be argued that firms with high environmental costs may use a separate cost pool for environmental costs. This implies that firms with high environmental costs are more likely to perceive EMA techniques as important and, in turn, they will appreciate the benefits that are derived from those techniques.Based on the above discussion the following hypothesis are tested:

H7: There is a positive association between the percentage of environmental costs to the total overhead costs and the accountants' perception of the importance of EMA techniques.

H8: There is a positive association between the percentage of environmental costs to the total overhead costs and the accountants' perception of the importance of benefits derived from EMA techniques

4 Research Design and Data Collection

A questionnaire was used to collect the data. A random sample consisting of 100 certified accountants was chosen from Bahrain Accountants Association. The questionnaire was distributed by hand and collected by post. Distributing questionnaires by hand allowed for face to face interaction with respondents. Efforts have been made in order to encourage respondents to answer. A total number of 36 questionnaires were returned.This yielded a response rate of 36%.

The questionnaire included three sections. In section (A), two questions were included relating to the importance attached to EMA's techniques and the importance of benefits derived from EMA's techniques. Section (B) included 5 questions relating to four contextual variables which are: number of employees, type of business industries, level of competition, and cost structure. The final section, section (C), contained questions relating to demographic data including length of time working at the organization and length of time of qualifying as an accountant. Respondents were asked to tick a box if they want to receive a copy of the results.31 respondents ticked this box; therefore, the content of this questionnaire was of particular importance to the respondents.

It is widely accepted that a covering letter is a motivation tool (De Vaus, 2013). Therefore, the cover letter incorporated statements that could encourage accountants to complete the questionnaire. Also, the definition of basic concepts used is included to make sure that concepts were defined clearly. A copy of the questionnaire and covering letter are shown in appendix (A). To ascertain the validity of the questionnaire, it was distributed to a sample of 10 persons (5 academics and 5 accountants). They suggested some amendments and clarifications of some items. After taking their comments into account, a final version of the questionnaire was ready to send out to the accountants.

A non-response bias test, based on the assumption that later respondents more closely resemble nonrespondents was undertaken, by comparing the early 10 responses with the last 10 responses in respect of all variables used in the research. The results indicated that there was no significant difference between early and late responses; therefore, there was no evidence of non-response bias.

4.1 Measurement of the Variables

The following sub-sections discussed the measurement of each of the variable included in this study.

4.1.1 Size of the Organization

The contingency theory literature used many proxies for measuring company size. According to Mullins(2007), size is not a simple variable" and the most common measure of the size variable is the number of em-ployees in the company (Ahmed and Courtis, 1999). Similarly, Bjørnenak (1997) suggested that the number of employees to measure a company's size is one way to discriminate between firms' sizes. Also, Christ and Burritt (2013) used the number of employees as a measure of the size of the organization. In this study, respondents were given two groups of employees. The first one less than 50 employees and the second one is more than 50 employees. This method is used to distinguish between small and large size organizations. The two groups were used for many reasons. First, the pilot study revealed that it was easy for respondents to answer without referring to the organizations' records. Second, it is consistent with the argument of research methodology that suggests low response rate in the case of asking respondent for referring to company's data(Dillman, 2000). Finally, Christ and Burritt (2013) used four groups of employees and then group respondents into two groups because there were a very low number of respondents in other groups.

4.1.2 Intensity of Competition

The intensity of competition was measured using a question adapted from Khandwalla (1972). Respondents were asked to indicate the level of competition in the market place for the major products/services of their companies. The scale is ranging from 1 (Not intensive at all) to 5 (Extremely intensive).

4.1.3 Type of Industry

There are two methods that may be used in order to measure the type of industry. The first method was developed by Deegan and Gordon (1996). In this method, respondents were asked to rank their industries on a scale of 1 to 5 (5= being most environmental sensitive). The second method was to use the classification of environmentally sensitive industries that appeared in the previous literature. Deegan and Gordon (1996) determined the more sensitive environmentally sensitive industries. They include uranium mining, chemicals,coal, transport, oil and gas explorers and producers, plastics manufacturing, gas distributors, and forest, paper,and pulp. Christ and Burritt (2013) used this classification and industries that had not included were grouped together as "less environmentally sensitive". This study used two groups; one is for less environmentally sensitive and the other is for high environmentally sensitive. The first page of the questionnaire includes a list of industries that are considered environmentally sensitive.

4.1.4 Cost Structure

Respondents were asked to specify the percentage of environmental costs to the total overhead costs. Respondents were accountants working at their organizations and, therefore, it is expected that they are familiar with the percentage of environmental costs.

4.1.5 Perceived Importance of EMA Techniques

According to United Nations Division for Sustainable Development (2001), EMA includes the following:

Estimation of annual environmental costs.

Product pricing

Budgeting

Investment appraisal, calculating investment options

Calculating costs, savings, and benefits of environmental projects

Environmental performance evaluation including indicators and benchmarking

Setting quantified performance targets

EMA techniques are measured using an instrument adapted from prior studies. Burritt et al. (2010) develop 12 items relating to EMA activities drawn from prior academic and professional literature. The respondents were asked to indicate on a seven-point Likert scale the extent to which each of the 12 items was used in their organizations over the last three years. Burritt et al. (2010), used three anchors; 0= Has not done at all,3= Has done to some extent, and 6= Has done to a great extent.

The 12 items used by Burritt et al. (2010)were:

(1) Identification of environment-related costs.

(2) Estimation of environment-related contingent liabilities.

(3) Classification of environment-related costs.

(4) Allocation of environment-related costs to production processes.

(5) Allocation of environment-related costs to products.

(6) Introduction or improvement to environment-related cost management.

(7) Creation and use of environment-related cost accounts.

(8) Development and use of environment-related key performance indicators (KPIs).

(9) Product life cycle cost assessments.

(10) Product inventory analyses.

(11) Product impact analyses.

(12) Product improvement analysis.

Staniskis and Stasiskiene (2006) pointed out that case studies in Lithuanian industries indicated that there is a need for adequate treatment of contingent costs for the assessment of investment decisions. According to Christ and Burritt (2013), the techniques did not cover the assessment of environmental impacts on capital investment decision. They included additional item relating to the assessment of potential environmental impacts associated with the capital investment decision. Therefore, the total number of items included in the construct was added up to 13 items. However, there is a difference in the construct developed by Christ and Burritt (2013) is that it focused on the extent to which respondents believed that their organizations would engage in the 13 activities in the next three years. In other words, Burritt et al. (2010) focused on current use;however, Christ and Burritt (2013) focused on future use. In the current study, 13 items were used but respondents were asked to indicate the perceived importance attached to each item. Also, the current study used a five-point Likert Scale since respondents would find it difficult to answer on seven-point scale as indicated through the pilot study. Respondents were asked to indicate the level of importance attached to each technique. The scale is ranging from 1(not important at all) to 5 (extremely important).

4.1.6 Perceived Benefits Derived from EMA Techniques

There are several potential benefits attributed to EMA. These include cost reductions, improved product pricing, the attraction of human resources, and reputational improvements(Bennett et al., 2003; Burritt et al.,2002). Also, EMA can provide different information for decision maker that may help in better waste management processes, reduced energy and material consumption or opportunities for material recycling (Adams and Zutshi, 2004, Bennett et al., 2003, Burritt et al., 2002). Similarly, Gale (2006) claimed that the adoption of EMA is likely to lead to cost saving opportunities and opportunities to create value within current activities.Also, Lee (2012) argued that firms may achieve cost-saving through ecological efficiencies. Furthermore,EMA could enhance quality performance and create competitive advantage (Dunk, 2007).To summarize, benefits derived from EMA include:

Determining hidden environmental costs (United Nations Division for Sustainable Development, 2001;Gale, 2006)

Cost reduction (Bennett et al., 2003; Burritt et al., 2002; Burritt and Saka, 2006; De Beer and Friend, 2006)

Cost saving (Lee, 2012)

Enhance innovation (Hendro et al., 2008)

Cleaner production (Gale, 2006)

Better product pricing (Staniskis and Stasiskiene, 2006)

Increased shareholders value (Staniskis and Stasiskiene, 2006)

Enhance performance quality (Dunk, 2007)

Create competitive advantages (Dunk, 2007)

Respondents were asked to indicate the level of importance attached to each benefit derived from each technique. The scale is ranging from 1(not important at all) to 5 (extremely important).

5 Research Findings

Responses indicated that 13 (36.1%) of respondents were qualified as accountants for a period less than 2 year, 15 (41.7%) of respondents were qualified for a period ranging from 2-5 years, and 8 (22.2%) of respondents were qualified for more than 5 years. Similarly, 17 (47.2%) of respondents were working at the company for a period less than 2 year, 10 (27.8%) of respondents were working at the company for a period ranging from 2-5 years, and 9 (25%) of respondents were working at the company for a period more than 5 year.

The respondents were assigned different degrees of importance to each of EMA's techniques. The most important technique was the identification of environmental-related costs with Mean = 3.22. This implies that environmental costs determination was the initial step that triggered the other techniques. In other words, determination of environmental costs can lead to better product pricing, incorporating environmental costs into investment decisions, product life cycle cost assessment, and the others techniques. In addition, respondents perceived that better product pricing as being the most important benefit derived from EMA's techniques. The Mean equals to 3. The insensitivity of competition may interpret such results. In other words, when the intensity of competition increase, the importance attached to pricing decision would increase (see Table1).

Table 1 Descriptive statistic for the importance attached to EMA's techniques and to benefits driven from EMA's techniques

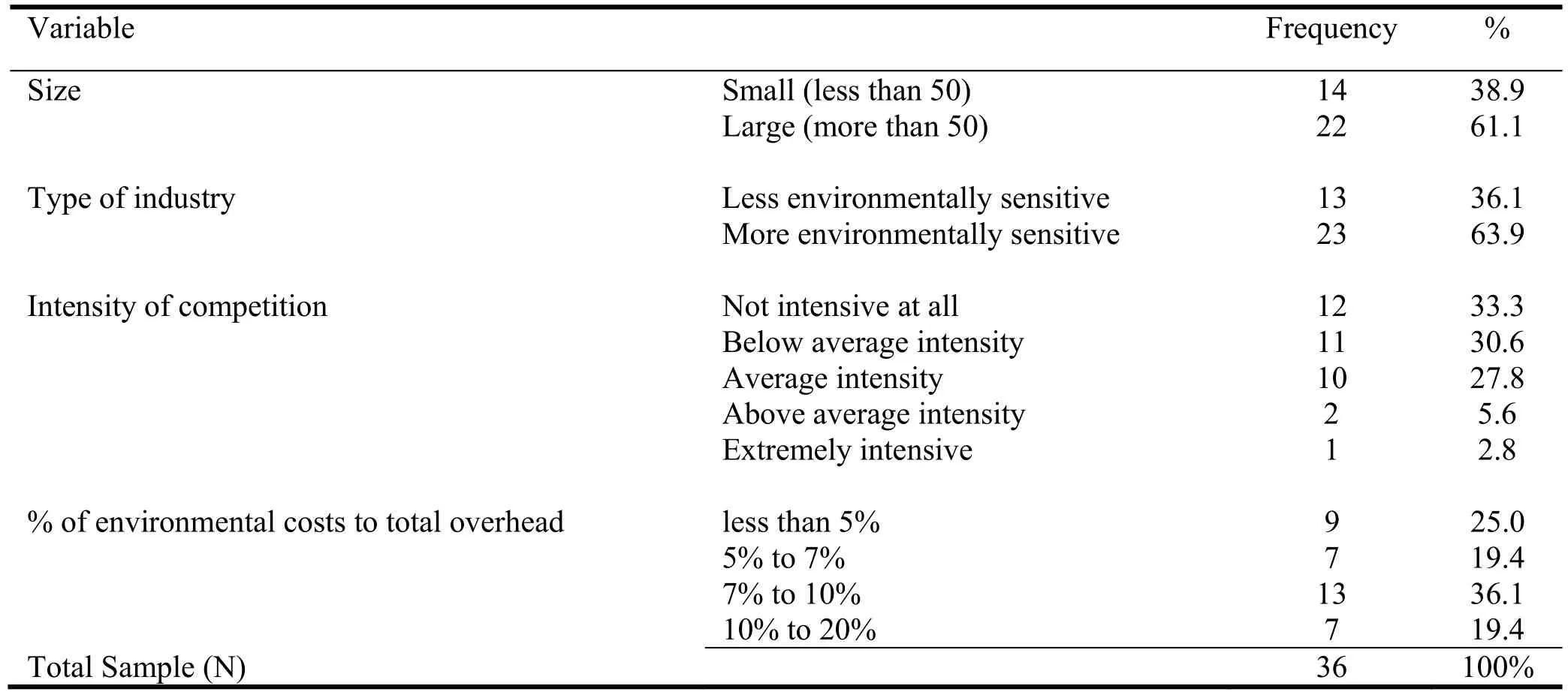

14 (38.9%) of respondents were from small size companies; however, 22 (61.1%) of respondents were at large size companies. Regarding the type of industry, 13 (36.1%) of respondents from industries that were less environmentally sensitive and 23 (63.9%) of respondents were from industries that were more environmentally sensitive. There were different levels of intensity of competition. It is clearly observed that 12(33.3%) of respondents indicated that the competition is not intensive at all, 11 (30.6%) of respondents perceived that the competition is below average intensity, 10 (27.8%) of respondents indicated that there were average intensity of competition, 2 (5.6%) of respondents perceived that the level of competition was above average, and only one respondent perceived that the competition was extremely intensive. Therefore, most respondents (63.9%) were perceived that the intensity of competition is below average or not intensive at all.Also, the responses indicated that 9 (25%) respondents determined that the percentage of environmental costs to the total overhead was less than 5%, 7 (19.4%) respondents determined that the percentage was ranging from 5 to 7%, 13 (36.1%) respondents perceived that the percentage was ranging from 7 to 10%, and 7(19.4%) of respondents determined that the percentage was ranging from 10 to 20% (see Table 2).

Table 2 Descriptive statistics for size, type of industry, intensity of competition, % of environmental costs to total overhead

It should be noted that the importance attached to EMA's techniques and the importance attached to benefits derived from EMA's techniques are measured using multiple items instruments. There are two methods that could be used in aggregating multiple items instruments. The first method is the average score. This method of aggregating the multiple items that measure a variable is explained by (Hoyle et al., 2002). They demonstrated that, when an individual indicates his or her own attitude (or opinion) relating to an object on some scales, a substantial element of intuitive judgment is involved, no matter how precise the rating instructions and no matter how well trained the individual. Such judgment in the use of rating scales makes the ratings vulnerable to bias. Averaging the scores for several variable items reduces this bias. On the other hand,the second method is to aggregate the multiple-item instruments using factor analysis. Many researchers(Bryman and Cramer, 2002; Cortina, 1993; Oppenheim, 2000) argue that factor analysis is a useful tool in order to aggregate variables and to test for an instrument's homogeneity and unidimensionality. This technique involves the use of different methods. One of these methods, and probably the most famous one, is the principal-component method where factors are extracted with Eigenvalues of more than one.

Bearing the two methods of aggregating variables in mind, the multiple-item instruments (i.e. the importance of EMA and importance of benefits derived from EMA) were aggregated using the average score.For management accounting research, Foster and Swenson (1997) claimed that a composite score has the advantage over an individual single question when either (1) the variable being measured contains multiple dimensional aspects requiring several different questions to capture the multiple dimensional aspects, or (2)there is a measurement error in an individual question that is diversified away in aggregating individual questions into a composite. Nunally and Bernstein (1978) suggested that the use of factor analysis is likely to overestimate the number of dimensions of the instruments. It is easier to interpret the aggregating of multipleitem instruments using the average score than factor analysis which is sometimes difficult to interpret without a subjective judgment.

It is widely recognized that Cronbach Alpha is used to measure the reliability of an Instrument. Therefore,it was used to measure the reliability of the 13-items that were used to measure the importance attached to EMA's techniques. Cronbach Alpha was 0.967 that suggesting a high level of reliability. Also, Cronbach Alpha was 0.846 for the 9 items that were sued to measure benefits derived from EMA's techniques.

Table 3 Correlations between importance attached to EMA's techniques and contextual variables

Table 4 Regression model (dependent variable: importance attached to EMA's techniques

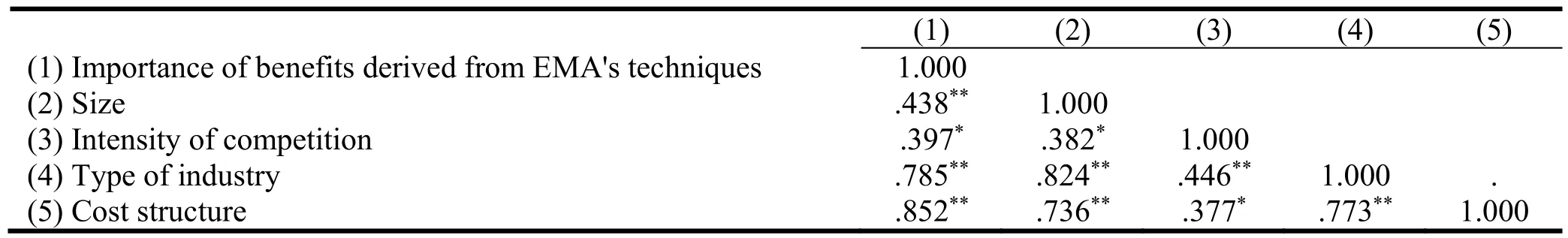

Table 5 Correlations between the importance of benefits derived from EMA's techniques and contextual variables

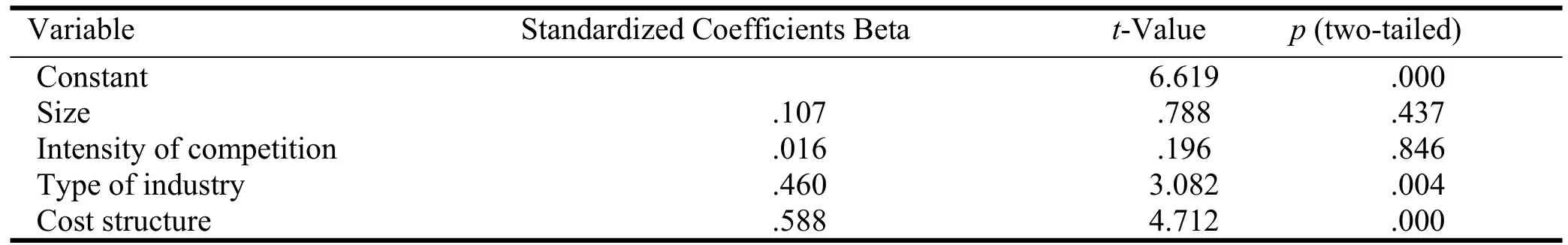

Table 6 Regression model (dependent variable: importance of benefits derived from EMA's techniques

To test for hypotheses, correlation coefficients were used to test the association between the importance attached to EMA's techniques and contextual variables. It should be noted that the correlation coefficient is ranging from -1 to +1. A correlation of +1 means perfect positive correlation. However, a correlation of -1 means perfect negative correlation. However, a correlation of zero indicates that there is no relationship between variables (Bryman and Cramer, 2002). It is clearly observed that there was a correlation between the importance attached to EMA's techniques and the four contextual variables. The correlation coefficient between the importance attached to EMA's techniques and size was the highest (coefficient = 0.725) and significant at 0.01 level. However, the correlation coefficient between the importance attached to EMA's techniques and intensity of competition was the lowest (coefficient = 0.428) and significant at 0.01 level (see Table 3).

A regression model was used to test hypotheses relating to the importance attached to EMA's techniques(hypotheses 1, 3, 5, and 7). The Overall model was found to be significant (F= 48.362,p=.000). Adjusted R square equaled .844 that represented independent variables were explained 84.4% of the variations in the importance attached to EMA's techniques. The significant relationship between the importance attached to EMA's techniques and size (Beta =.257,t= 2.094,p=.044 < 0.05), type of industry (Beta =.481,t= 3.576,p=.001 < 0.05), and cost structure (Beta =.238,t= 2.115,p=.043 < 0.05). There was no significant relation-ship between the intensity of competition and the importance attached to EMA' techniques (Beta =.038,t=505,p=.617) (see Table 4).

Furthermore, there was a correlation between the importance of benefits derived from EMA's techniques and the four contextual variables. The correlation coefficient between the importance of benefits derived from EMA's techniques and cost structure was the highest (coefficient = .852) and significant at 0.01 level.However, the correlation coefficient between the importance of benefits derived from EMA's techniques and intensity of competition was the lowest (coefficient = .397) and significant at 0.05 level (see Table 5). A regression model was used to test hypotheses relating to the importance of benefits derived from EMA's techniques (hypotheses 2, 4, 6, and 8). The overall model was found to be significant (F= 37.946,p=.000).Adjusted R square = .809 that represented independent variables were explained 80.9% of the variations in the importance of benefits derived from to EMA's techniques. The significant relationship between the importance of benefits derived from to EMA's techniques and type of industry (Beta =.460,t= 3.082,p=.004< 0.05) and cost structure (Beta =.588,t= 4.712,p=.000 < 0.05). There was no significant relationship between the importance of benefits derived from to EMA's techniques and the size (Beta =.107,t= .788,p=.437), and the intensity of competition (Beta =.016,t= .196,p=.846 (see Table 6).

6 Conclusions

The results indicated that there were significant relationships between the importance attached to EMA's techniques and size, type of industry, and cost structure. The results were consistent with contingency theory literature (e.g.: Chenhall and Morris, 1986; Gordon and Narayanan, 1984) and EMA's literature (e.g. Christ and Burritt, 2013, Frost and Wilmshurst, 1998). In addition, the results were consistent with the evidence obtained from case studies in different countries (e.g.: Bennett et al., 2003; Jasch, 2003; Papaspyropoulos et al., 2012).

The EMA's literature (e.g.: Burritt et al., 2002; Burritt and Saka, 2006; De Beer and Friend, 2006; Gale,2006) provided many normative arguments to the benefits derived from EMA's techniques; however, it seemed that there was no attempt to test such arguments empirically. The results indicated that there were significant relationships between the importance of benefits derived from EMA's techniques and type of industry and cost structure. This implied that companies that were working in the environmentally sensitive industry with a high percentage of environmental costs would perceive high importance to EMA's techniques.

Overall this study contributed to the literature of EMA in many aspects. First, it provided results relating to accountants’ perception of the importance of EMA's techniques in Bahrain; however, the previous studies were undertaken in developed countries. Second, the current study examined factors that influence the importance of benefits derived from EMA's techniques; however, prior studies were focusing on a normative argument of such benefits. Finally, the results of this study may encourage companies that are working in Bahrain to adopt EMA's techniques to achieve benefits that are demonstrated.

This study is subject to limitations of surveys including response rate and representation of sample to the population. It should be noted that efforts have been made to increase the response rate including distributing the questionnaire by hand and selecting a random sample. Also, a brief definition of concepts was included on the first page of the questionnaire to make sure that respondents answered according to the correct meaning.Furthermore, a non-response bias is always a problem with the survey. However, the results indicated that there was no existence of non-response bias.

Drawing off the results of this study, there are many areas of future research. First, future research may focus on the relationship between other contextual variables and EMA. In addition, the future study could be done in the public sector (see, for example, Nuhu et al., 2017) Second, the current research may be duplicated in other countries in order to analyze the difference in EMA's practice among countries. Third, the current study revealed that the percentage of environmental costs and type of industry are the significant factors influencing the importance attached to benefits derived from EMA's techniques. More specifically, the research may focus on how companies adopt and use EMA techniques in order to face environmental risks (see, for example, Bui and de Villiers, 2017). Future research may focus on examining cost system design in terms of allocation of environmental costs to cost centers and products or services. Finally, future research may focus on the flow of environmental information across the organization and examine whether companies use accounting data base or incorporating it with other information systems.

Abrahamson, E. (1991), Managerial fads and fashions: The diffusion and rejection of innovations,Academy of Management Review16, 586-612.

Adams, C. and Zutshi, A. (2004), Corporate social responsibility: Why business should act responsibly and be accountable,Australian Accounting Review14, 31-39.

Ahmed, K. and Courtis, J.K. (1999), Associations between corporate characteristics and disclosure levels in annual reports: a metaanalysis,The British Accounting Review31, 35-61.

Bennett, M., Rikhardsson, P. and Schaltegger, S. (2003),Adopting environmental management accounting: EMA as a value-adding activity, Environmental Management Accounting—Purpose and Progress. Springer.

Bjørnenak, T. (1997), Diffusion and accounting: the case of ABC in Norway,Management Accounting Research8, 3-17.

Brierley, J.A., Cowton, C.J. and Drury, C. (2001), Research into product costing practice: A European perspective,European Accounting Review10, 215-256.

Bryman, A. and Cramer, D. (2002),Quantitative data analysis with SPSS release 8 for Windows: a guide for social scientists,Routledge.

Bui, B. and De Villiers, C. (2017), Business strategies and management accounting in response to climate change risk exposure and regulatory uncertainty,The British Accounting Review49, 4-24.

Burritt, R.L. (2004), Environmental management accounting: roadblocks on the way to the green and pleasant land,Business Strategy and the Environment13, 13-32.

Burritt, R.L., Hahn, T. and Schaltegger, S. (2002), Towards a comprehensive framework for environmental management accounting—Links between business actors and environmental management accounting tools,Australian Accounting Review12, 39-50.

Burritt, R.L. and Saka, C. (2006), Environmental management accounting applications and eco-efficiency: case studies from Japan,Journal of Cleaner Production14, 1262-1275.

Burritt, R.L., Schaltegger, S., Bennett, M., Pohjola, T. and Csutora, M. (2011),Environmental management accounting and supply chain management, Springer Science & Business Media.

Burritt, R.L., Schaltegger, S., Ferreira, A., Moulang, C. and Hendro, B. (2010), Environmental management accounting and innovation: an exploratory analysis,Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal23, 920-948.

Chenhall, R.H. 2003, Management control systems design within its organizational context: findings from contingency-based research and directions for the future,Accounting, Organizations and Society28, 127-168.

Chenhall, R.H. and Morris, D. (1986), The impact of structure, environment, and interdependence on the perceived usefulness of management accounting systems,Accounting Review16-35.

Christ, K.L. and Burritt, R.L. (2013), Environmental management accounting: the significance of contingent variables for adoption,Journal of Cleaner Production41, 163-173.

Cooper, R. and Kaplan, R. (1987),Accounting and Management, Field Study Perspectives. Boston.

Cortina, J.M. (1993), What is coefficient alpha? An examination of theory and applications,Journal of Applied Psychology78, 98.

De Beer, P. and Friend, F. (2006), Environmental accounting: A management tool for enhancing corporate environmental and economic performance,Ecological Economics58, 548-560.

De Vaus, D. (2013),Surveys in social research, Routledge.

Deegan, C. and Gordon, B. (1996), A study of the environmental disclosure practices of Australian corporations,Accounting and Business Research26, 187-199.

United Nations Division for Sustainable Development (2001),Environmental management accounting procedures and principles, UN.www.un.org/esa/sustdev/publications/proceduresandprinciples.pdf.

Dillman, D.A. (2000),Mail and internet surveys: The tailored design method,Wiley New York.

Drazin, R. and Van De Ven, A.H. (1985), Alternative forms of fit in contingency theory,Administrative Science Quarterly, 514-539.

Dunk, A.S. (2007), Assessing the effects of product quality and environmental management accounting on the competitive advantage of firms,Australasian Accounting Business & Finance Journal1, 28.

Epstein, M.J. and Young, S.D. (1999), "Greening" with EVA,Strategic Finance80, 45.

Ezzamei, M. (1990), The impact of environmental uncertainty, managerial autonomy and size on budget characteristics,Management Accounting Research1, 181-197.

Foster, G. and Swenson, D.W. (1997), Measuring the success of activity-based cost management and its determinants,Journal of Management Accounting Research9, 109.

Frost, G.R. and Wilmshurst, T.D. (1998), Evidence of environmental accounting in Australian companies,Asian Review of Accounting6, 163-180.

Gale, R. (2006), Environmental costs at a Canadian paper mill: A case study of Environmental Management Accounting (EMA),Journal of Cleaner Production14, 1237-1251.

Gordon, L.A. and Miller, D. (1976), A contingency framework for the design of accounting information systems,Accounting, Organizations and Society1, 59-69.

Gordon, L.A. and Narayanan, V.K. (1984), Management accounting systems, perceived environmental uncertainty and organization structure: an empirical investigation,Accounting, Organizations and Society9, 33-47.

Hendro, B., Ferreira, A. and Moulang, C. (2008),Does the use of environmental management accounting affect innovation? An exploratory analysis.31 st Annual Congress of the European Accounting Association, 2008.

Hoyle, R.H., Harris, M.J. and Judd, C.M. (2002),Research methods in social relations, Thomson Learning.

Jasch, C. (2003), The use of Environmental Management Accounting (EMA) for identifying environmental costs,Journal of Cleaner Production11, 667-676.

Jasch, C. (2006), How to perform an environmental management cost assessment in one day,Journal of Cleaner Production14,1194-1213.

Jasch, C. (2011),Environmental Management Accounting: Comparing and Linking Requirements at Micro and Macro Levels–A Practitioner’s View. Environmental Management Accounting and Supply Chain Management. Springer.

Khandwalla, P.N. (1972), The effect of different types of competition on the use of management controls,Journal of Accounting Research275-285.

Lee, K.-H. (2012), Carbon accounting for supply chain management in the automobile industry,Journal of Cleaner Production36,83-93.

Libby, T. and Waterhouse, J.H. (1996), Predicting change in management accounting systems,Journal of Management Accounting Research8, 137.

Luft, J. and Shields, M.D. (2003), Mapping management accounting: graphics and guidelines for theory-consistent empirical research,Accounting, Organizations and Society28, 169-249.

Medley, P. (1997), Environmental accounting-What does it mean to professional accountants?Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal10, 594-600.

Merchant, K.A. (1981), The design of the corporate budgeting system: influences on managerial behavior and performance,Accounting Review813-829.

Moores, K. and Chenhall, R. (1994), Framework and MAS evidence,Strategic Management Accounting: Australian Cases12-26.

Mullins, L.J. (2007),Management and organisational behaviour, Pearson education.

Nuhu, N.A., Baird, K. and Bala Appuhamilage, A. (2017), The adoption and success of contemporary management accounting practices in the public sector,Asian Review of Accounting25, 234-238.

Nually, J.C. and Bernstein, I.H. (1978),Psychometric theory.New York: McGraw-Hill.

Oppenheim, A.N. (2000),Questionnaire design, interviewing and attitude measurement,Bloomsbury Publishing.

Otley, D.T. (1980), The contingency theory of management accounting: achievement and prognosis,Accounting, Organizations and Society5, 413-428.

Papaspyropoulos, K.G., Blioumis, V., Christodoulou, A.S., Birtsas, P.K. and Skordas, K.E. (2012), Challenges in implementing environmental management accounting tools: the case of a nonprofit forestry organization,Journal of Cleaner Production29, 132-143.

Savage, D. and Jasch, C. (2004),International Guidelines on Environmental Management Accounting (EMA).International Federation of Accountants, New York.

Schaltegger, S., Hahn, T. and Burritt, R. (2000),Environmental management accounting: Overview and main approaches, Center for Sustainability Management.

Schaltegger, S., Viere, T. and Zvezdov, D. (2012), Tapping environmental accounting potentials of beer brewing: Information needs for successful cleaner production,Journal of Cleaner Production29, 1-10.

Shields, M.D. (1997), Research in management accounting by North Americans in the 1990s,Journal of Management Accounting Research9, 3.

Simons, R. (1990), The role of management control systems in creating competitive advantage: new perspectives,Accounting, Organizations and Society15, 127-143.

Staniskis, J.K. and Stasiskiene, Z. (2006), Environmental management accounting in Lithuania: exploratory study of current practices,opportunities and strategic intents,Journal of Cleaner Production14, 1252-1261.

Williamson, O.E. (1970),Corporate control and business behavior: An inquiry into the effects of organization form on enterprise behavior,Prentice Hall.

Xiaomei, L. (2004), Theory and practice of environmental management accounting,International Journal of Technology Management& Sustainable Development3, 47-57.

Journal of Environmental Accounting and Management2018年1期

Journal of Environmental Accounting and Management2018年1期

- Journal of Environmental Accounting and Management的其它文章

- The Relationship Between Environment Operational Performance and Environmental Disclosure of Nigerian Listed Companies

- Analyzing Structure and Driving Force of Steel Consumption in China

- Ecological Interstate Systems as an Object of Legal Research

- Examining the Effect of Emotion to the Online Shopping Stores’ Service Recovery: A Meta-Analysis

- A Risk-averse Two-Stage Stochastic Optimization Model for Water Resources Allocation under Uncertainty

- Disclosure of Environmental Matters – Galp Energy