The Relationship Between Environment Operational Performance and Environmental Disclosure of Nigerian Listed Companies

Magaji Abba, Ridzwana Mohd Said, Amalina Abdullah, Fauziah Mahat1 Department of Accounting and Finance, Faculty of Management Science, Abubakar Tafawa Balewa University Bauchi, Nigeria

2. Department of Accounting and Finance, Faculty of Economics and Management, University Putra Malaysia

1 Introduction

The UN conference of 1972 was the first formal nation states appreciation of environmental concern posed by companies’ activities that affect the eco-system. The environmental and sustainability issues were deliberated,with urgent need for measures that will safeguard the world from climate change effects. This gave rise to the establishment of UN Environmental Programme (UNEP), saddled with environmental protection promotion programmes. Subsequently, regular discourse about the environmental protection were held. In particular, the Brundland report of 1987 was popular which suggested for wholehearted approach to environmental sustainability and development. In 1992, the UN Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED) sought the adoption of Agenda 21. The agenda provides index measures that will help sustain the environment into a considerable future time. Similar UN conventions, up recent Paris submit of 2017, reassert the need to reduce companies’ carbon emissions that degrades the environment and the eco-system. Though, large volume of the emissions come from industrialised nations, developing countries suffer most of the negative effect.

In context, Nigeria is a developing economy witnessing tremendous economic and social development brought about by democracy and trade liberation. It proliferated private companies’ participations in manufacturing activities that led to excessive demand of environmental resources. This scramble for the use of the resource suffuses the environment with pollutants that impact negatively on the eco-system. Earlier studies by Ayoola (2011), and Bala et al. (2012) noted that Nigerian companies’ activities result in environmental degradation, resource depletion, land destruction, emissions, and pollution into air water, all of which, affect the environment.

Local communities and the government is therefore confronted with this emerging issue of companies’environmental impacts (Afolabi et al., 2012; Ayoola, 2011; Ngwakwe, 2009). This attracts public discourse about environmental performance by regulators and non-governmental organisations. It gives rise to movements that coerce and entice the companies to be environmentally considerate in their operations. The carrot and stick approach is used,i.e.punish environmental transgressors with fines and sanctions and reward environment-friendly companies with incentives, waivers, awards and patronage. As a result, many companies incorporate environmental measures as part of their management practices.

Therefore environmental performance (EP) is a company’s efforts towards environmental responsiveness.This is reflected by the impact companies’ operations have on the natural environment and the efforts put to control and reduce the negative effects on the environment (Alrazi et al., 2015). EP is viewed by Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) as a product or service related impacts of a company’s operations to the environment,and the compliance with legislation aimed at protecting the environment (Initiatives, 2014). The performance measures the company’s efficiency in resource consumption, energy utilisation, waste production and control,emissions, effluents controls, and any effort towards the management of operational activities that affect the environment.

Nevertheless, Nigeria is slow in response to the increased concern about environmental aspects of the companies activities (Adekoya and Ekpenyong, 2009; Hassan and Kouhy, 2014). Regardless of the efforts made by the country in adopting Agenda 21 of 1992 Rio conference (reaffirmed at the World Summit on Sustainable Development in Johannesburg 2002) to address environmental issues, oil spills, emissions, pollution,and environmental degradation have remained the greatest problems in Nigeria (Uwuigbe and Uadiale, 2011).Even with the recent interest promoted by environmentalists from developed countries, United Nations (UN),and local communities, environmental activities of the companies is worrisome. This is because substantial number of the companies operating in the country discharge liquid, solids and gaseous wastes into the environment. This happen without adequate treatment that meets the basic international standards (Omofonmwan and Osa-Edoh, 2008; Uwuigbe and Uadiale, 2011).

To ease the public and regulatory pressure, companies resort to the disclosure of environmental activities and portray themselves as environment-friendly entities. However, the disclosure is doubted as a true reflection of the performance (He and Loftus, 2014; Sutantoputra et al., 2012). The work of Dawkins and Fraas(2011) noted that companies use the disclosure to suppress public attention from their poor performance (instead of a rightful commitment to environmental activities). This gives rise to a green-wash problem in the disclosure. Delmas and Burbano (2011) observed that the disclosure may not necessarily depict the actual performance. Thus, a questions can be asked on whether the environmental disclosure (ED) by the Nigerian manufacturing companies reflects actual performance. This is because those companies with legitimacy is-sues about the performance can make superfluous disclosure of environmental items to serve public relation function instead of a true commitment to environmental issues.

Scholars mostly used competing theories to explain environmental behaviour and disclosure of the companies. For example, Cormier et al. (2011); Villiers and van Staden (2011) studies using legitimacy theory report an inverse relationship between environmental performance and environmental disclosure. Therefore,the disclosure is seen as a functional legitimisation to divert public outcry and attention. The work of Clarkson et al. (2011) however, used voluntary disclosure theory to explicate that high performed companies resort to differentiation strategy by disclosing hard and quality items which cannot be mimicked by the less environment considerate companies.

The used of the competing theories jam-packed the prior studies of the environmental performance and environmental disclosure with inconsistent findings (Clarkson et al., 2008). This might be due to the effect of environmental performance on environmental disclosure as suggested by the voluntary disclosure theory(Clarkson et al., 2011). This position however, goes against de Villiers and van Staden (2006) assertion of legitimisation effect of the disclosure. The problem with the prior studies is in the operationalisation of the environmental performance (Endrikat et al., 2014). They rely on a single measure of performance in the form of ranking and award instead of comprehensive measures put in place by companies to protect the environment (Albertini, 2013). Similarly, Trumpp et al. (2015) assert that environmental performance is a multidimensional construct which a single indicator will not capture the companies’ overall environmental commitment. Montabon et al. (2007); Rao et al. (2009) specify that environmental performance measures must be internally focused, from floor-level operational activities. It should involves activities that relate to resource consumption and the resultant output of emissions and pollution.

Therefore, the objective of the study is to examine the relationship between environment operational performance and environmental disclosure of public listed companies in Nigeria. The study contributes to the understanding of the relationship between the performance and the disclosure. It also contributes to measurement issues observed in the prior studies by using an alternative measure of the environmental performance.This is achieved through the performance measure from floor-level operational activities as suggested by Rao et al. (2009); Trumpp et al. (2015), and Montabon et al. (2007) who advocated the internal focus in the measurement. It also espouses the green-wash-issue in Nigerian companies’ environmental disclosure and underscores the legitimacy theory assertion. That is, the environmental disclosure by the Nigerian companies is to serve legitimacy issue rather than a true commitment to environmental sustainability.

1.1 Environment operational performance (EOP)

Frequent judgements are being made about companies’ environmental performance, without any particular stand being attained about its standardisation (Henri and Journeault, 2010). This is due to the individualistic conception of the performance by researchers. For example, Luo et al. (2015) referred the performance as a company’s efforts towards maximum resources utilisations, emissions reduction, and environment-friendly product innovation. Walls et al. (2011) viewed performance as a product of environmental management strategy to reduce the negative impact of companies’ activities on the physical environment. Brammer and Pavelin(2006, 2008) used reports of the UK environmental agency perception of the performance as the amount of court fine charged on the company because of environmental transgressions. While, Sutantoputra et al. (2012)viewed it as waste management, the amount of emissions, and adoption of environmental management system reported in Corporate Monitor. Aerts and Cormier (2009) viewed the performance as a level of exposure a company received from media resulted from pollution activities.

It can be seen that previous research have provided an extensive view of the performance but failed to achieve a common stand, thus measurement standardisation problem persists. The present study conceived environmental performance from the operational level, as the level of efficient resources consumption, materials, energy, water, and the resultant levels of emissions, pollution, and wastewater discharge into the environment. This conception is in line with the Montabon et al. (2007); Rao et al. (2009); Xie and Hayase (2007)who suggested for floor-level operations in the measure of companies’ environmental performance.

1.2 Environmental disclosure (ED)

The separation of ownership and management of public companies gives rise to information asymmetries between the managers as agents and the shareholders as principals (Villiers and van Staden, 2011). This is because the shareholders are external to the company who do not participate in day-to-day affairs of the company. This limits them from direct access to all internal management information and operational procedures. In order to meet the needs of wider stakeholders and to reduce information asymmetry companies disclose information in the annual reports (Healy and Palepu, 2001), Apart from the mandatory financial statement disclosures, companies make additional voluntary disclosure, such as, environmental performance to the public.

The environmental disclosure (ED) provides information about companies’ environmental activities and efforts undertaken towards environmental sustainability. Campbell (2004) beheld ED as any report that pertains to a company’s organisational process or operation that impact the natural environment. It is a medium through which companies display transparent and accountable behaviour to stakeholders about their environmental performance which is reported in companies’ annual reports, stand-alone reports or companies’ websites.

Similar to environmental performance, empirical literature did not provide an all-accepted conception of the disclosure (Alrazi et al., 2015). This is because of the differences in the purpose for which the disclosure is being made, the target recipients of the information, and the researcher’s perspective (Cormier et al., 2011;da Silva Monteiro and Aibar-Guzmán, 2010; Dawkins and Fraas, 2011). Meek et al. (1995) defined voluntary disclosure as reporting in excess of requirements, representing a free choice by a company’s management to provide accounting and information to the users. The reporting is usually made in the companies’ annual reports for use in decision making. It includes information on environmental impacts, risks, policies, strategies,targets, costs and liabilities.

The voluntary nature of the disclosure allows the companies to decide on the environmental items to disclose and items not to disclose, either in qualitative and/or quantitative, past, current or future. Environmental disclosure is important to both companies and other interested users as it helps satisfy accountability function of stakeholders’ information needs and public relations (Sumiani et al., 2007). It serves as an indicator of companies’ consciousness to environmental issues. In spite of the value relevance of the disclosure information, green-wash and un-standardisation issues limit the disclosure usefulness (Delmas and Burbano, 2011;He and Loftus, 2014; Sutantoputra et al., 2012).

Based on the above-given definitions, environmental disclosures can be construed as any statement and information made public by a company relating to environmental policies, plans (mainly environmental management schemes) and declarations; investments in pollution abatement devices and processes; pollution remediation; recycling activities; recognition of the company’s polluting effects; and pollution fines and any other environmental cost, investment or benefit. The disclosure is made on either soft-unverifiable (level)claims or hard-verifiable items (quality) or both, depending on the companies’ motives (Christina and Janice,2014; Clarkson et al., 2013; Clarkson et al., 2011). While soft and high level disclosure items are more of public relations function to correct legitimacy issue, and disclosure of hard items are made to achieve differentiation and favourable selection.

The disclosure quality are verifiable items of governance structures and systems, the presence of a unit or department for management of environmental activities, environment concern unit, environment supplydemand chain policy, and ISO implementations among others; Credibility items relate to reporting guidelines and adoption of GRI, third-party assurance of environmental commitment, environmental awards, environmental programmes, interactions with environmental agencies and the like; Environmental performance indicators are items that exhibit efficiency in resources utilisations, pollution and pollution management, expenditures on environmental controls and prevention of negative impacts. On the other hand, the soft disclosure items include visions and strategic claims about environmental commitments, environment policy objectives,a management system for risk control, profile about environmental compliance, a statement about environmental sensitivity, environment initiative efforts, accident response plan, the award for employees environment commitment, local community involvement in environmental programmes.

2 Literature Review and Hypotheses

The relationship between environmental performance and environmental disclosure can be explained by the legitimacy and voluntary disclosure theories. Voluntary disclosure theory is surmised on strategic disclosure as a medium of differentiation adopted by environmentally performing companies to acquire selection advantage. Clarkson et al. (2011) explained that high-performed companies distinguish themselves from poor performers with voluntary disclosure of quality items which are difficult to imitate. The intention is to entice favourable business dealing with the public. Therefore, a positive relationship between environmental performance and disclosure quality is predicted in this study.

Legitimacy theory is premised on the legitimization effect of environmental disclosures and public relations strategy. Deegan and Blomquist (2006); Spence et al. (2010) argued that companies make disclosures to present themselves as legitimate entities that operate within the societal expected norms. This is particularly relevant when a company’s environmental performance is threatened. Thus, more disclosure level is made to divert stakeholders’ attention from their poor performance. Similarly, Aerts and Cormier (2009);Bebbington et al. (2008); Dawkins and Fraas (2011) opined that disclosure is a function of social and political pressures that a company suffers. Companies make more disclosure of soft-unverifiable (level) items to distract public scrutiny and avoid legislative sanctions and fines. The goal is to suppress stakeholders’ pressure that can impinge on their legitimacy and survival. Therefore, this theory suggests a negative relationship between environmental performance and the level of disclosure.

With the theories predicting opposite directions of the relationship, it is not surprising that previous studies report mixed findings (He and Loftus, 2014). The studies that show no and negative relationships displays the relevance of legitimacy theory, while the ones that support voluntary theory argument report positive relationships. For example, Ingram and Frazier (1980) attributed the findings of no relationships between environmental performance and environmental disclosure to the poor quality of environmental disclosures in annual reports. Similar findings were reported in studies by Wiseman (1982) and Freedman and Wasley (1990).Hughes et al. (2001) modified Wiseman index to examine whether the disclosures are consistent with environmental performance ratings (good, mixed, and poor) by the Council for Economic Priority. They found a negative relationship between the performance and disclosure. Consistently, findings in Patten’s (2002) and Villiers and van Staden (2011) revealed a negative relationship between performance and disclosure. They assert that “managers of the company with bad environmental reputations provide additional disclosures to providers of financial capital to explain how they manage environmental issues” (Villiers and van Staden,2011). Later in 2011, Cormier et al. (2011b) documented a negative relationship between company emission level and disclosure. The companies with legitimacy threat make high-level disclosures. In the same context,Delmas and Montes-Sancho (2010) report a negative relationship, stressing that companies that make high disclosure are those with high-level toxic releases and least compliance with environmental laws.

Nevertheless, Sutantoputra et al. (2012) questioned the validity of the companies’ environmental disclosure as a true reflection of actual environmental performance. They examined the relationship between the performance, and the disclosure level and quality of 53 large Australian companies. The results revealed that poor performers disclosed favourable information to counter public pressure and to avoid sanctions. But no evidence of good performers disclose more than poor performers. In contrast, when a company environmental reputation is sound, it makes much more verifiable disclosures to distinguish itself from the poor performers.

Al-Tuwaijri et al. (2004) examined the relations among environmental disclosure, environmental performance and economic performance by applying simultaneous equations approach. A content analysis on 198 US companies showed a significant positive relationship between environmental performance and economic performance, and a positive relationship between environmental performance and environmental disclosure.It further supported that good performer report more than poor performers, thus a positive relationship exists between the performance and quality disclosures. Clarkson et al. (2008) revisited this relationships by testing the two competing predictions about the relationships made by voluntary disclosure theory and socio-political theory. They conducted content analysis using Global Reporting Initiatives index (GRI) to measure companies’ disclosure, and found a negative association between the performance and the disclosure level. This is consistent with legitimacy theory that poor performers report more to correct their bad image. However, this contradicted the voluntary disclosure theory which state that good environmental performers report more of their environmental performance.

Clarkson et al. (2011) examined the associations between environmental performance, and both the level and the quality of voluntary environmental disclosures on 51 Australian companies. The results showed a negative relationship between the environmental performance and high-disclosure. Good performers report quality items, and rely on the disclosures to communicate their differences, indicating a positive relationship.Similar results were also found by Wu and Shen (2010) in their study of 145 listed companies in China’s chemical industry.

In sum, the voluntary disclosure theory suggests that companies with proven good environmental performance disclose more “hard and verifiable” (quality) environmental information, which is difficult for poor performing company to imitate. This enables them to distinguish themselves from the poor performing companies, and enjoy selection preference. Thus, a positive relationship is expected to exist.

Thus, the following hypothesis are addressed:

H1.There is a negative relationship between environment operational performance and environmental disclosure

H1a:There is a negative relationship between environmental operational performance and environmental disclosure level.

H1b:There is a positive relationship between environment operational performance and environmental disclosure quality

3 Method and Measures

The population of the manufacturing industry in Nigerian Stock Exchange Market (NSE) as at December 2015 is 77 companies. This industry is chosen due to possible environmental implications of its business activities. The final sample of 53 companies were selected which represents 68.83% of the population. Even though the number appears small, this is common in many environmental accounting literature (see for example, Sutantoputra et al. (2012); Clarkson et al. (2011); Sumiani et al. (2007); Hassan and Kouhy (2014)).

3.1 Environmental disclosure index measure

The publicity nature of annual report provides a first choice medium through which companies report their environmental activities. It has been indicated that information provided via company’s annual report provides a first reference point to many shareholders groups (de Villiers and van Staden, 2006; Deegan, 2002).Therefore, it is expected that the information in this report is reliable.

Environmental disclosure data is gathered based on Clarkson et al. (2008) measurement approach which was developed from GRI index that focuses “on company disclosures related to its commitment to protect the environment” (p.305). They provide different environmental information ranked according to the disclosure items. The items are grouped into Governance structure and management systems (6); Credibility (10); Environmental performance indicators, EPI (60); Environmental spending (3); Vision and strategy claims (6); Environmental profile (4); Environmental initiatives (6).

Many recent studies adhered to the Clarkson et al. (2008) measurement, adopting the GRI index. For example, Christina and Janice (2014); Iatridis (2013); Moroney et al. (2012); Sutantoputra et al. (2012). The popularity of the index measure was further echoed by Moroney et al. (2012) such that the index provides indicators framework that are credible and acceptable for environmental reporting by companies. Quality disclosure is reflected with the disclosure of both positive and negative environmental activities that can be comparable, reliable and accurate to a greater extent.

3.1.1 Content Analysis

Content analysis was used to gather information related to environmental disclosure. The method transformed narrative texts and code them into a numeric value that allows inferences and replications (Vourvachis and Woodward, 2015). It is “a research technique for making replicable and valid inferences from texts (or other meaningful matter) to the contexts of their use”(Krippendorff, 2012). The texts are classified into scales for stress-free assessment that will facilitate the achievement of designed aim.

The choice of the annual report for the analysis is due to its nature where companies communicate at least annually to the wider public. Many environmental accounting studies extract the performance information by content analysis of companies’ reports (for example, Christina and Janice (2014); Hassan and Kouhy (2014);He and Loftus (2014); He et al. (2013). Meanwhile, the Clarkson et al. (2008) index is divided into verifiable(hard/quality) and unverifiable (soft/level) disclosure items. It is further categorised into seven sub-group,where governance and management system, credibility, Environmental Performance Indicators (EPI) and environmental spending are quality items. The items assess a company’s actual commitment to the environmental performance in an objective manner. Besides that, the disclosure level items are grouped into company strategy and vision statement, environmental profile and environmental initiatives. The level and quality of environmental disclosures are extracted from annual reports for the year 2015.

3.1.2 Environmental disclosure level (EDL)

The environmental disclosure level is concerned with the quantity of the items disclosed irrespective of the nature or value of the information content. No particular dichotomy is made between general and specific statements, either quantitative or qualitative. The purpose is to assess the breadth of the disclosure (Hooks and van Staden, 2011). It is measured by Clarkson et al. (2008) soft disclosure items which are categorised into Vision and strategy (6 items), environmental profile (4 items), and environmental initiatives (6 items). A binary system of 1 (disclosed) and 0 (not disclosed) is used to get a total score for each category.

3.1.3 Environmental disclosure quality (EDQ)

The assessment of the environmental disclosure quality is necessary because of the need for information value relevance. The aim is to make distinctions between good environmental performers and poor performers by the ranking of the index, and assignment of high scores for hard disclosure items.

The hard items of the Clarkson et al. (2008) index are used to capture the disclosure quality, as the items considered the value relevance of the disclosures. They are sub-grouped into governance and management system (6 scores), credibility (10 scores), EPI (60 rank-scores), and environmental spending (3). More weight is given to EPI items because of its importance to environmental issues. Therefore, where an item is disclosed,1 is given and if not, 0 is scored. For EPI items the scores are ranked into six scales relative to the detail and specificity. The measure provides for the specificity and credibility of the disclosure about true environmental commitment.

3.2 Environment operational performance (EOP)

Many previous studies measured environmental performance with a single indicator as a proxy for the performance. This approach subjected the findings to intense criticism, particularly, from environmental management scholars who argued that a single indicator measure suffers validity problem (Xie and Hayase, 2007).Trumpp et al. (2015) claim that the construct requires several variables to achieve validity, and suggest for a measure that considers both inputs and outputs indicators arising from floor-level operational activities. Rao et al. (2009); Trumpp et al. (2015); Xie and Hayase (2007) supported this approach because of its ability to capture the fundamental impacts of environmental activities across companies operating in different industries.

Due to the absence of readable environmental data in the Nigerian companies, survey questionnaire was used to gather information on environment operational performance and were distributed to the operation managers of the manufacturing companies. It contained 16 questions about a company’s resources consumption and pollution outputs and ranked on a scale of 1 to 7. The instrument extends EMS-ISO index with 0.858 overall Cronbach-Alpha level of reliability. Similarly, normality test on the EOP data returned skewness of -0.134 and standard error of 0.327, a kurtosis of -0.771 and standard error of 0.644. This falls within the accepted level of -2 to 2 (McDonald and Ho, 2002).

4 Model Specification

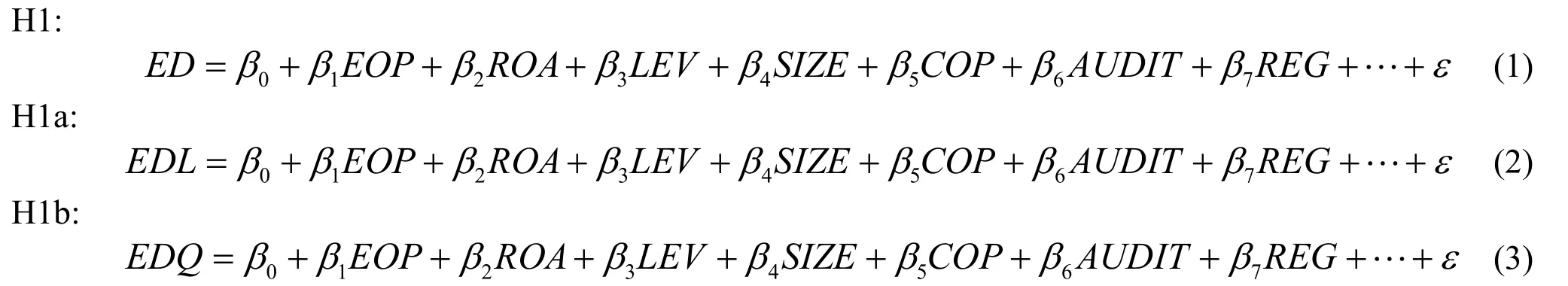

Apart from the EOP, ED, EDL and ED, other variables are included into the models as control variables. The variables commonly affect companies’ environmental performance and disclosure. For example, size, profitability, leverage, regulatory pressure, competitiveness, and audit quality are proven to have effect on the environmental performance and environmental disclosures, see Cho et al. (2010); Gao and Connors (2011); He and Loftus (2014); He et al. (2013); Huang and Kung (2010). Thus, this study used the models below to test the earlier hypotheses:

where

The analysis is made based on Ordinary Least Square (OLS), 2Stage Least Square (2SLS), and 3Stage Least Square (3SLS). This is in order improve the outcome of the regressions and to avoid shortcoming of the OLS. Wooldridge (2010) claimed that analysis of results based on 2SLS are more consistent than OLS results. Likewise, Hayashi (2000) provides that further analysis with 3SLS improve the consistency as the regression equations are reduced to seemingly unrelated regressions.

5 Results and Discussions

As stated earlier, the environmental performance is measured from floor-level activities to capture all company’s operational behaviour that has a direct effect on the environment. The disclosures are measured with Clarkson et al. (2008) index. The index measure is gaining popularity in environmental accounting research because of the distinction it made between soft from hard disclosure items. A STATA 13 software is used for the descriptive, correlation, and regression analyses of the data.

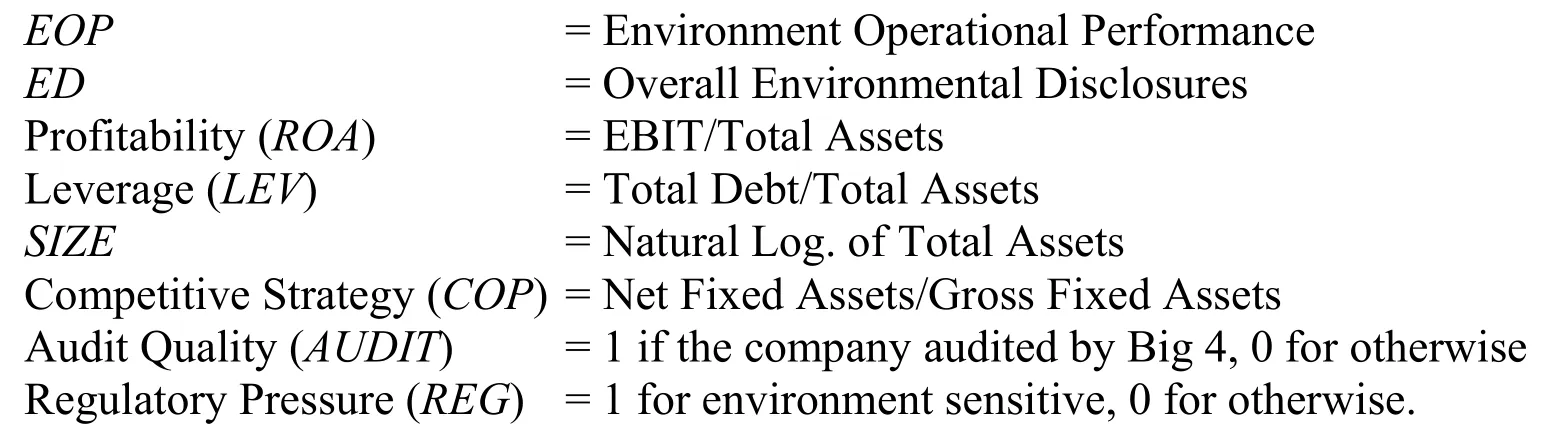

5.1 Descriptive analysis

The summary of the descriptive analysis result is shown in Table 1 below. It can be seen that ED, EDL and EDQ have mean scores of 52.264, 27.245 and 25.019, and standard deviation of 12.277, 4.883 and 8.291, respectively. These show a lower variability of the scores around the means. Similarly, apart from ROA with a higher standard deviation of 20.681 all the other exogenous variables are fairly stable around the mean.

Table 1 Descriptive Statistics

Table 2 Correlation results on environment operational performance and environmental disclosures

5.2 Correlation results on environment operational performance and environmental disclosures

An analysis of correlations among the variables was made to examine the magnitude of the relationships necessary for further estimations of the regressions. The analysis was made using Spearman correlation, and the results are presented in Table 2. It shows the matrix among all the variable of interest of H1, H1a, H1b. It can be observed that the relationships between EOP, ED, and EDL are negatively related with 0.667, 0.4236 coefficients, respectively. This points to an inverse relationship between the variables. When EOP is low, ED and EDL are high, thus, and poor environment operational performance goes with high disclosures. However, the correlation between the EOP and EDQ is positive (0.182) but weak, showing a negligible parallel relationship.Earlier works on environmental accounting assumed environmental disclosures are reflective of environmental performance. But later concerns emerged about the relationship as non-performing companies make fictitious claims about their performance which are not true environmental commitment. This is because of the green-wash issue observed by Delmas et al. (2011) study of US companies.

Table 3 Regression results on environment operational performance and environmental disclosure

5.3 Regression results on environment operational performance and environmental disclosures

Further regression analysis is made with the disclosures as endogenous and environment operational performance as exogenous, together with some other controls variables. The results are shown in Table 3 above,with the first box revealing results about H1, the second box representing results of H1a, and the third box showing H1b results. It can be seen from the first box OLS column with R-square of 0.535, a significant negative relationship between the disclosure and the performance with 0.166 coefficient and standard error of 0.0372 at 10%p-value. Under 2SLS column with R-square of 0.748, the effect falls to a negative coefficient of 0.0589 at 5% significant level and standard error of 0.0328. Whereas 3SLS with R-square of 0.748 showed improved outcome, the standard error is reduced to 0.0299 and the coefficient remains unchanged at the 0.0589. Overall, the result showed a significant negative relationship. In effect, 1% change in EOP results in 0.0589 negative change in ED of the Nigerian manufacturing companies. Therefore, the companies’ environ-mental disclosures served the intended purpose of legitimisation process. This implies that the companies make more disclosure where their legitimacy is threatened due to low environmental performance.

The control variable in the first box, ROA, is significant and positive at 5%p-value with 0.984 coefficient on the 3SLS model. This shows that as ROA increased, more disclosures are made to provide the public with information environmental performance. The disclosure is used to justify that high profit is achievable with an environmental performance that is the benefits driven from environmental performance outweigh the costs incurred. This result supported the findings of Cho et al. (2010); Clarkson et al. (2008); Uwuigbe and Egbide(2012); Uwuigbe and Uadiale (2011). Company’s leverage also has a significant positive coefficient of 0.187 and standard error of 0.0956 at 10%p-value. Thus, as a company’s debts mix in the capital structure increases,environmental disclosure increases. This is to avoid information asymmetric risk that may arise due to communication gaps. Similar findings were found in studies by Bouten et al. (2012); Clarkson et al. (2008); He et al. (2013); Huang and Kung (2010); Iatridis (2013), under different contexts, reported a positive effect of leverage on disclosures. Audit quality shows a significant positive effect in all the models, model (3) provides 0.588 coefficient at 1%p-value, standard error of 0.139. The positive relationship corroborate that companies that are being audited by Big 4 audit firms make more disclosures with the improved environmental performance (Bewley and Li, 2000; Huang and Kung, 2010).

The negative findings relating to the EOP and the ED is consistent with the legitimacy theory. The theory explains that where company’s legitimacy is threatened by poor environmental performance, more disclosure is normally made to educate, change or divert public attention from the companies’ irresponsible environmental behaviour. This theoretical support was espoused in Adams and McNicholas (2007); Aerts et al. (2006);Alrazi et al. (2015); Bebbington et al. (2008); Dawkins and Fraas (2011); Delmas and Burbano (2011). They affirmed the legitimacy role in companies’ disclosure to make public informed about companies’ environmental performance efforts.

Similarly, empirical literature has examined the relationship, where this work contributed to a different approach to the operationalization of environmental performance measure. The works of Clarkson et al.(2008); Cormier et al. (2011); Patten (2002); Sutantoputra et al. (2012); Villiers and van Staden (2011) have supported the negative relationship. While Al-Tuwaijri et al. (2004); Clarkson et al. (2011); Iatridis (2013)works reported positive findings.

This outcome indicates that manufacturing companies in Nigeria use the disclosure to legitimatise their existence in the society. They use the tactics to maintain, counter, change public perception about their environmental performance. More disclosures are being made when company’s environmental performance is low, and less disclosures are made when performance is high.

This can be due to the increase in agitation by non-governmental organisations and regulatory pressure in the country. It provides the companies with the opportunity to safeguard its licence to operate.

The second box in Table 3 shows the results of H1a which is concerned with environment operational performance and disclosure level. Scholars argued that less performing companies engaged in a high-level disclosure of unverifiable items to counter legitimacy threat. A regression analysis is made with the disclosure level as the endogenous variable while the operational performance and the other control variables as explanatory variables.

The OLS results revealed an R-square of 0.860 is achieved, and it is improved in 2SLS and 3SLS to 0.869.The regression output from OLS is significant and negative with 0.319 coefficient and standard error of 0.0293 at 1%p-value. 2SLS results are also significant and negative with 0.291 and 0.0293 at 1%p-value.Further analysis with 3SLS reinforces the significant negative effect of the performance on the level of disclosure with a 0.291 at 1%p-value and standard error of 0.0266. It suggested that for 1% change in EOP results to a negative 0.291 changes in EDL. Accordingly, this implies that high-level disclosures are made where the environment operational performance is low.

Meanwhile, leverage is positive with 0.233 significant level at 5% in the model (1) and (2), while 3SLS improved the result to 1% significant level. It shows that the level of debt financing of the companies affect the disclosure level. High-level debt capital results in high-level disclosure of environmental information.This positive result is supported by Brammer and Pavelin (2006); Clarkson et al. (2008); Huang and Kung(2010).

REG has a negative and significant effect on the disclosure level with 0.286 coefficient at 5%p-value.This indicates that high-level disclosures suppress authorities and public concern about companies’ negative environmental impact. This is to satisfy the information needs of the stakeholders and suppress public pressure on the companies’ environmental performance. It presupposes the notion that regulatory pressure makes the companies disclose high-level environmental information to avoid sanctions and intervention. The works by Brammer and Pavelin (2006); Cho and Patten (2007); Huang and Kung (2010) stipulated that those companies that are in the eye of regulators, communicate extensively to avoid sanctions. However, sometimes,more disclosures are made to entice regulators towards incentives, as first movers of environmentally responsible actions.

In sum, the results indicate that companies make high-level disclosure when their environmental performance is low. When companies’ performance is improved, less disclosure is made. However, this scenario does not happen without reason, because the disclosure has both preparation costs and information costs which do not contribute directly to profit (López-Gamero et al., 2009). Thus, the disclosure is made when a company’s legitimacy is at stake.

This is also consistent with the legitimacy theory in which disclosure is more of a legitimisation strategy used by companies to correct, divert and /or avoid public scrutiny because of poor their environmental responsibility. Previous studies by Adams and McNicholas (2007); Aerts and Cormier (2009); Bebbington et al.(2008); Clarkson et al. (2008); Dawkins and Fraas (2011); de Villiers and van Staden (2006) supported the legitimisation role of environmental disclosure by companies.

Similarly, empirical findings of earlier scholars are in conformity with a negative relationship between environmental performance and level of environmental disclosure. For example, see the works of Clarkson et al.(2008); Cormier et al.(2011a); He et al. (2013); Sutantoputra et al. (2012); Villiers and van Staden (2011). In contrast, Al-Tuwaijri et al. (2004); Dawkins and Fraas (2011); Wu and Shen (2010) reported positive relationship. While others like Freedman and Wasley (1990); Ingram and Frazier (1980); Wiseman (1982) reported no relationship.

Though empirical evidence is inconsistent, the findings on H1a is justified with the theoretical underpins and the reported result. This shows that the Nigerian companies’ make more disclosure level when their legitimacy is put in jeopardy by the concerned stakeholders. An example is a case of environmental movements in the Niger Delta region which attracts international attention. The companies operating in the region engaged the locals, provides amenities, health facilities, and observe the international code of practice in their operations. They make more and wider publicity of their environmental efforts to counter the negative media visibility.

Finally, the third box shows results of H1b which is about the environmental performance and disclosure quality. An R-square of 0.411, and 0.488 is achieved in column one, and two and three, respectively. The regression results between the EOP and EDQ under the pool (0.028), 2SLS (-0.00417), 3SLS (-0.00417) are not significant.

ROA is negatively related with 0.100 coefficient at 10% significant level in the pool, improved to 5% level under 2SLS and 3SLS with -0.0828 coefficients. SIZE has a significant positive effect with a coefficient value of 0.228 at 10%p-value in the pool, and improved in 2SLS (0.489) and 3SLS (0.489) to 0.05p-value.AUDIT also is positive and significant with 0.248 coefficient at 10%p-value in the pool, improved to 0.05%p-value in the 2SLS (0.240), and 3SLS (0.248) with a standard error of 0.126. While all the other control variables are non-significant. Accordingly, the results reveal no relationship between companies’ environment operational performance and disclosure quality.

The voluntary disclosure theory promoted by Clarkson et al. (2011) did not support the environmental disclosure reporting in Nigerian case. However, this can be due to the development level of the country where environmental information values relevance is not much appreciated. For example, Belal et al. (2013); Elijido-Ten (2004); Hassan and Kouhy (2014) have observed that developing countries have little concern about environmental issues, making them vulnerable to exploitation tendencies due poor regulatory enforcement. In addition, Fifka (2012) reported environmental accounting in developing countries are in embryo stage with less disclosure of activities. Earlier work of de Villiers and van Staden (2006) under South African context,reported low environmental disclosure in developing countries due to low development, poor regulatory enforcement, and public awareness.

The previous research shows significant relationship, this can be connected to the measure of the performance. For example, the use of ranking, awards and /or media visibility allow companies to fiddle in order to score high in the performance (Delmas and Burbano, 2011).

6 Conclusion

Companies’ environmental activities perplex both the regulators and the environmental stakeholders. This is because of the negative impacts that arise from use of the natural resources and pollutions therefrom. It thus required the companies to engage in activities that control and reduce its effect on the natural environment.Companies also report about their activities as environmental disclosure. Nevertheless, the disclosure is doubted as a true reflection of the performance because of green-wash issue.

This study examined the relationship between the environmental performance and disclosure of listed companies in Nigeria. The result showed a significant negative effect of the performance on overall and disclosure level. It means that the companies in Nigeria make more disclosure level when their environmental performance is poor. The disclosure is made to counter legitimacy issues related to their environmental performance which is perceived by the wider stakeholders as not effective. Though, the high level of environmental disclosure might not necessarily represent actual performance.

To capture the value relevance of the disclosure, the relationship between environmental disclosure quality and environmental performance was examined. Surprisingly, the result did not support the expectations that a positive relationship exists between the disclosure quality and environmental performance. This finding is plausible given the underdeveloped nature of Nigeria where the environmental reporting is still at its infancy level. It can also be attributed to the complex nature of the environmental activities which can obscure the companies in deciding the most relevant items to disclose.

However, this study is not without its limitations. This study used cross-sectional data in which the data may not be static and behave consistently across the companies. In addition, the sample is small and constrained due to the small number of Nigerian companies listed in the Stock Exchange. Thus, future studies may consider a longitudinal approach with time series that cover at least five years period. The use of alternative theory is also recommended, in particular, resource-based theory to examine the relationship between environmental performance and environmental disclosure quality.

Adams, C.A. and McNicholas, P. (2007), Making a difference: sustainability reporting, accountability and organisational change,Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal20(3), 382-402.

Adekoya, A. and Ekpenyong, E. (2009),Corporate governance and environmental performance: Three point strategy for improving environmental performance among corporations in Africa Symposium conducted at the meeting of the IAIA 09 Conference Proceedings.

Aerts, W. and Cormier, D. (2009), Media legitimacy and corporate environmental communication,Accounting, Organizations and Society34(1), 1-27.

Aerts, W., Cormier, D. and Magnan, M. (2006), Intra-industry imitation in corporate environmental reporting: An international perspective,Journal of Accounting and Public Policy25(3), 299-331.

Afolabi, A., Francis, F.A. and Adejompo, F. (2012), Assessment of health and environmental challenges of cement factory on Ewekoro community residents, Ogun State, Nigeria,American Journal of Human Ecology1(2), 51-57.

Al-Tuwaijri, S.A., Christensen, T.E. and Hughes Ii, K. (2004), The relations among environmental disclosure, environmental performance, and economic performance: A simultaneous equations approach,Accounting, Organizations and Society29(5), 447-471.

Albertini, E. (2013), Does environmental management improve financial performance? A meta-analytical review,Organization &Environment26(4), 431-457.

Alrazi, B., de Villiers, C. and van Staden, C.J. (2015), A comprehensive literature review on, and the construction of a framework for,environmental legitimacy, accountability and proactivity,Journal of Cleaner Production102, 44-57.

Ayoola, T.J. (2011), Gas flaring and its implication for environmental accounting in Nigeria,Journal of Sustainable Development4(5),244-250.

Bala, J., Yusuf, I. and Tahir, F. (2012), Bacteriological assessment of pharmaceutical wastewater and its public health implications in Nigeria,The IUP Journal of Biotechnology6(1), 34-49.

Bebbington, J., Larrinaga-González, C. and Moneva-Abadía, J.M. (2008), Legitimating reputation/the reputation of legitimacy theory,Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal21(3), 371-374.

Belal, A.R., Cooper, S.M. and Roberts, R.W. (2013),Vulnerable and exploitable: The need for organisational accountability and transparency in emerging and less developed economies, Symposium conducted at the meeting of the Accounting Forum.

Bewley, K. and Li, Y. (2000), Disclosure of environmental information by Canadian manufacturing companies: A voluntary disclosure perspective,Advances in Environmental Accounting & Management1(1), 201-226.

Bouten, L., Everaert, P. and Roberts, R.W. (2012), How a two-step approach discloses different determinants of voluntary social and environmental reporting,Journal of Business Finance & Accounting39(5-6), 567-605.

Brammer, S. and Pavelin, S. (2006), Voluntary environmental disclosures by large UK companies,Journal of Business Finance &Accounting33(7-8), 1168-1188.

Brammer, S. and Pavelin, S. (2008), Factors influencing the quality of corporate environmental disclosure,Business Strategy and the Environment17(2), 120-136.

Campbell, D. (2004), A longitudinal and cross-sectional analysis of environmental disclosure in UK companies - a research note,The British Accounting Review36(1), 107-117.

Cho, C.H. and Patten, D.M. (2007), The role of environmental disclosures as tools of legitimacy: A research note,Accounting, Organizations and Society32(7-8), 639-647.

Cho, C.H., Roberts, R.W. and Patten, D.M. (2010), The language of US corporate environmental disclosure,Accounting, Organizations and Society35(4), 431-443.

Christina, H. and Janice, L. (2014), Does environmental reporting reflect environmental performance?Pacific Accounting Review26(1/2), 134-154.

Clarkson, P.M., Fang, X., Li, Y. and Richardson, G. (2013), The relevance of environmental disclosures: Are such disclosures incrementally informative?Journal of Accounting and Public Policy32(5), 410-431.

Clarkson, P.M., Li, Y., Richardson, G.D. and Vasvari, F.P. (2008), Revisiting the relation between environmental performance and environmental disclosure: An empirical analysis,Accounting, Organizations and Society33(4), 303-327.

Clarkson, P.M., Overell, M.B. and Chapple, L. (2011), Environmental reporting and its relation to corporate environmental performance,Abacus47(1), 27-60.

Cormier, D., Ledoux, M.-J. and Magnan, M. (2011), The informational contribution of social and environmental disclosures for investors,Management Decision49(8), 1276-1304.

da Silva Monteiro, S.M. and Aibar-Guzmán, B. (2010), Determinants of environmental disclosure in the annual reports of large companies operating in Portugal,Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management17(4), 185-204.

Dawkins, C.E. and Fraas, J.W. (2011), Erratum to: Beyond acclamations and excuses: Environmental performance, voluntary environmental disclosure and the role of visibility,Journal of Business Ethics99(3), 383-397.

de Villiers, C. and van Staden, C.J. (2006), Can less environmental disclosure have a legitimising effect? Evidence from Africa,Accounting, Organizations and Society31(8), 763-781.

Deegan, C. (2002), Introduction: The legitimising effect of social and environmental disclosures - a theoretical foundation,Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal15(3), 282-311.

Deegan, C. and Blomquist, C. (2006), Stakeholder influence on corporate reporting: An exploration of the interaction between WWFAustralia and the Australian minerals industry,Accounting, Organizations and Society31(4-5), 343-372.

Delmas, M.A. and Burbano, V.C. (2011), The drivers of greenwashing,California Management Review54, 64-87.

Delmas, M.A. and Montes-Sancho, M.J. (2010), Voluntary agreements to improve environmental quality: Symbolic and substantive cooperation,Strategic Management Journal31(6), 575-601.

Elijido-Ten, E. (2004),Determinants of environmental disclosures in a developing country: An application of the stakeholder theory.Symposium conducted at the meeting of the Fourth Asia Pacific interdisciplinary research in accounting conference, Singapore

Endrikat, J., Guenther, E. and Hoppe, H. (2014), Making sense of conflicting empirical findings: A meta-analytic review of the relationship between corporate environmental and financial performance,European Management Journal32(5), 735-751.

Fifka, M. (2012), The development and state of research on social and environmental reporting in global comparison,Journal für Betriebswirtschaft62(1), 45-84.

Freedman, M. and Wasley, C. (1990), The association between environmental performance and environmental disclosure in annual reports and 10Ks,Advances in Public Interest Accounting3, 183-193.

Gao, L.S. and Connors, E. (2011), Corporate environmental performance, disclosure and leverage: An integrated approach,International Review of Accounting, Banking and Finance3(2), 1-26.

Hassan, A. and Kouhy, R. (2014), Time-series cross-sectional environmental performance and disclosure relationship: Specific evidence from a less-developed country,International Journal of Accounting and Economics Studies2(2), 60-73.

Hayashi, F. (2000),Econometrics. Princeton University Press. Section, 1, 60-69.

He, C. and Loftus, J. (2014), Does environmental reporting reflect environmental performance?Pacific Accounting Review26(1/2),134-154.

He, Y., Tang, Q. and Wang, K. (2013), Carbon disclosure, carbon performance, and cost of capital,China Journal of Accounting Studies1(3-4), 190-220.

Healy, P.M. and Palepu, K.G. (2001), Information asymmetry, corporate disclosure, and the capital markets: A review of the empirical disclosure literature,Journal of Accounting and Economics31(1-3), 405-440.

Henri, J.-F. and Journeault, M. (2010), Eco-control: The influence of management control systems on environmental and economic performance,Accounting, Organizations and Society35(1), 63-80.

Hooks, J. and van Staden, C.J. (2011), Evaluating environmental disclosures: The relationship between quality and extent measures,The British Accounting Review43(3), 200-213.

Huang, C.-L. and Kung, F.-H. (2010), Drivers of environmental disclosure and stakeholder expectation: Evidence from TaiwanJournal of Business Ethics96(3), 435-451.

Hughes, S.B., Anderson, A. and Golden, S. (2001), Corporate environmental disclosures: Are they useful in determining environmental performance?Journal of Accounting and Public Policy20(3), 217-240.

Iatridis, G.E. (2013), Environmental disclosure quality: Evidence on environmental performance, corporate governance and value relevance,Emerging Markets Review14(0), 55-75.

Ingram, R.W. and Frazier, K.B. (1980), Environmental performance and corporate disclosure,Journal of Accounting Research18(2),614-622.

Initiatives, G.R. (2014),G4 Sustainability Reporting Guidelines, 2013.Accessed October 26, 2016, from https://www.globalreporting.org.

Krippendorff, K. (2012),Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology(Vol. 456). The Annenberg School for Communication,University of Pennsylvania. Sage Inc.

López-Gamero, M.D., Molina-Azorín, J.F. and Claver-Cortés, E. (2009), The whole relationship between environmental variables and firm performance: Competitive advantage and firm resources as mediator variables,Journal of Environmental Management90(10), 3110-3121.

Luo, X., Wang, H., Raithel, S. and Zheng, Q. (2015), Corporate social performance, analyst stock recommendations, and firm future returns,Strategic Management Journal36(1), 123-136.

McDonald, R.P. and Ho, M.-H.R. (2002), Principles and practice in reporting structural equation analyses,Psychological methods7(1), 64.

Meek, G.K., Roberts, C.B. and Gray, S.J. (1995), Factors influencing voluntary annual report disclosures by U.S., U.K. and continental european multinational corporations,Journal of International Business Studies26(3), 555-572.

Montabon, F., Sroufe, R. and Narasimhan, R. (2007), An examination of corporate reporting, environmental management practices and firm performance, Journal of Operations Management 25(5), 998-1014.

Moroney, R., Windsor, C. and Aw, Y.T. (2012), Evidence of assurance enhancing the quality of voluntary environmental disclosures:An empirical analysis,Accounting & Finance52(3), 903-939.

Ngwakwe, C.C. (2009), Environmental responsibility and firm performance: Evidence from Nigeria,International Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences3(2), 97-103.

Omofonmwan, S. and Osa-Edoh, G. (2008), The challenges of environmental problems in Nigeria,Journal of human Ecology23(1),53-57.

Patten, D.M. (2002), The relation between environmental performance and environmental disclosure: a research note,Accounting,Organizations and Society27(8), 763-773.

Rao, P., Singh, A.K., la O'Castillo, O., Intal, P.S. and Sajid, A. (2009), A metric for corporate environmental indicators… for small and medium enterprises in the Philippines,Business strategy and the Environment18(1), 14-31.

Spence, C., Husillos, J. and Correa-Ruiz, C. (2010), Cargo cult science and the death of politics: A critical review of social and environmental accounting research,Critical Perspectives on Accounting21(1), 76-89.

Sumiani, Y., Haslinda, Y. and Lehman, G. (2007), Environmental reporting in a developing country: A case study on status and implementation in Malaysia,Journal of Cleaner Production15(10), 895-901.

Sutantoputra, A., Lindorff, M. and Johnson, E.P. (2012), The relationship between environmental performance and environmental disclosure,Australasian Journal of Environmental Management19(1), 51-65.

Trumpp, C., Endrikat, J., Zopf, C. and Guenther, E. (2015), Definition, conceptualization, and measurement of corporate environmental performance: A critical examination of a multidimensional construct,Journal of Business Ethics126(2), 185-204.

Uwuigbe, U. and Egbide, B.-C. (2012), Corporate social responsibility disclosures in Nigeria: A study of listed financial and nonfinancial firms,Journal of Management and Sustainability2(1), 160-169.

Uwuigbe, U. and Uadiale, O.M. (2011), Corporate Social and Environmental Disclosure in Nigeria: A Comparative Study of the Building Material and Brewery Industry,International Journal of Business and Management6(2), 258-264.

Villiers, C.D. and van Staden, C.J. (2011), Where firms choose to disclose voluntary environmental information,Journal of Accounting and Public Policy30(6), 504-525.

Vourvachis, P. and Woodward, T. (2015), Content analysis in social and environmental reporting research: Trends and challenges,Journal of Applied Accounting Research16(2), 166-195.

Walls, J.L., Phan, P.H. and Berrone, P. (2011), Measuring environmental strategy: Construct development, reliability, and validity,Business & Society50(1), 71-115.

Wiseman, J. (1982), An evaluation of environmental disclosures made in corporate annual reports,Accounting, Organizations and Society7(1), 53-63.

Wooldridge, J.M. (2010),Econometric analysis of cross section and panel data. MIT press.

Wu, H. and Shen, X. (2010),Environmental disclosure, environmental performance and firm value. Symposium conducted at the meeting of the E-Product E-Service and E-Entertainment (ICEEE), 2010 International Conference.

Xie, S. and Hayase, K. (2007), Corporate environmental performance evaluation: A measurement model and a new concept,Business Strategy and the Environment16(2), 148-168.

Zikmund, W.G. (2003),Business Research Methods, Mason, Ohio, South-Western. X the Restaurant Behaviour of the Berlin People.

Journal of Environmental Accounting and Management2018年1期

Journal of Environmental Accounting and Management2018年1期

- Journal of Environmental Accounting and Management的其它文章

- The Relationships Between Contextual Variables and Perceived Importance and Benefits of Environmental Management Accounting (EMA) Techniques

- Analyzing Structure and Driving Force of Steel Consumption in China

- Ecological Interstate Systems as an Object of Legal Research

- Examining the Effect of Emotion to the Online Shopping Stores’ Service Recovery: A Meta-Analysis

- A Risk-averse Two-Stage Stochastic Optimization Model for Water Resources Allocation under Uncertainty

- Disclosure of Environmental Matters – Galp Energy