Optimal and synchronized germination of Robinia pseudoacacia,Acacia dealbata and other woody Fabaceae using a handheld rotary tool:concomitant reduction of physical and physiological seed dormancy

Nuria Pedrol •Carolina G.Puig •Antonio López-Nogueira •María Pardo-Muras •Luís González•Pablo Souza-Alonso

Introduction

Seed germination takes place when conditions for establishing a new plant generation are suitable.Prior to germination and to complete this process,a widespread‘block’in the plant kingdom,seed dormancy,determines the developing processes(Finch-Savage and Leubner-Metzger 2006).This plays a key role in plant evolution since a dormant seed will not germinate in a speci fi ed period of time under any combination of physical environmental factors.Hence,seeds may survive dormant for many years and germinate only when ideal conditions exist(Wali 1999).This process can be viewed as an evolved dispersion strategy with a temporal pattern.

Dormancy and germination depend on seed structures,especially those surrounding the embryo,and factors affecting the embryo growth potential(Koornneef et al.2002).The seed external cover in angiosperms shows high diversities,including a wide range of adaptations to face adverse environmental conditions.The function of the seed coat is to protect the embryo and endosperm from desiccation,mechanical injury,unfavourable temperatures and attacks by bacteria,fungi and insects(Kelly et al.1992).Seeds are prevented from completing germination because the embryo is constrained by its surrounding structure,a phenomenon classi fi ed by Bewley(1997)ascoat enhanced dormancy,separating this from theembryo dormancy[classi fi cation of seed dormancy types may be reviewed in Baskin and Baskin(2004)].Embryo dormancy is characterized by a physiological inhibition of embryo growth and primordia protrusion,whereas in coat dormancy,the obstruction is conferred by the covering layers.Both embryo and coat dormancies are components of physiological dormancy and their sum and interaction determine the degree of‘whole-seed’physiological dormancy(Finch-Savage and Leubner-Metzger 2006).

The transition from dormancy to germination is a critical control point leading to the initiation of vegetative growth.Physiological processes that overcome seed dormancy include alterations in abscisic acid(ABA)and gibberellin(GA)synthesis and signalling,and appear to be similar among different species(Bentsink et al.2010;Linkies et al.2010).Speci fi cally,the net result of the dormant state seems to be highly reliant on general ABA/GA ratios(Finch-Savage and Leubner-Metzger 2006).

Outside the seed,many environmental factors control germination and dormancy such as light,temperature and the duration of storage(after ripening)(Koornneef et al.2002)but temperature is widely accepted as one of the major factors controlling the degree of dormancy(Baskin and Baskin 2004).Germination has a wide range of responses to environmental conditions and a range of conditions exists in which seeds from the same species germinate and others do not(Mayer and Poljakoff-Mayber 1982).

The Fabaceae is one of the largest families of plants with a worldwide distribution and has a major relevance in agriculture and agroforestry.Legumes are key components in ecosystem processes because of their association withRhizobiumbacteria,the main source of N2(nitrogen gas)fi xation in soils.They are also very useful for their role as N suppliers in agriculture but also for the restoration of degraded areas(Bradshaw 1997;Chaer et al.2011).This economically important family includes genera of nonedible woody legumes used worldwide as ornamental trees and shrubs(Acacia,Delonix,Gleditsia,Laburnum,MimosaandRobinia),industrially farmed for dyes(Indigofera)and gums(Acacia),and for timber production(Acacia,Castanospermum,DalbergiaandRobinia).

A hard seed coat impermeable to water is a typical feature of several species belonging to this taxonomic group,a valuable attribute for plant survival under adverse conditions(Teketay 1996;Smy kal et al.2014).Moreover,under natural conditions some leguminous species exploit their sprouting ability,decreasing their dependency on sexual reproduction in different degrees.Consequently,their germination percentages are usually lower than those of species which only reproduce sexually(Tárrega et al.1992).In nature,seed scari fi cation generally appears as one of the main processes favouring legume germination(Peinetti et al.1993;Watterson and Jones 2006;Twigg et al.2009),hence numerous efforts have been carried out to reproduce environmental factors triggering dormancy release,i.e.temperature(Tárrega et al.1992;Herranz et al.1998),chemical or mechanical scari fi cation(Janzen 1981;Zare etal.2011;Nongrum and Kharlukhi2013;Abudureheman et al.2014),mechanical abrasion(Vilela and Ravetta 2001),a combination of factors(Teketay 1996;Tigabu and Oden 2001;Sy et al.2001;Patane`and Gresta 2006)and even percussion(Khadduri and Harrington 2002;Mondoni et al.2013).In these cases,scari fi cation generally increased germination rates somewhat moderately.Nonetheless,current laboratory and greenhouse experimentation, fi eld trials,quality control by seed companies or in seed banks or plant nurseries for afforestation,timber and the biomass industry,as well as revegetation programs,require low-cost and highly reproducible methods to remove dormancy and to improve and synchronize germination at both small-and industrial scales.

In recent years,there have been a few approaches using rotary tools(also calledelectric grinders)as a scari fi cation method with remarkable results(Cruz and de Carvalho 2006;Ghantous and Sandler 2012;Dapont et al.2014).In this study,we aim to ameliorate the germination rates of several woody Fabaceae species through the application of a rotary tool by comparing its effectiveness with other conventional dormancy-breaking methods.We include different genera and life forms of species of ecological and economical importance such asRobinia pseudoacaciaL.,Acacia dealbataLink,Cytisus scoparius(L.)Link,C.multi fl orus(L’Hér.)Sweet andUlex europaeusL.Finally,a mode of action for the proposed method is suggested.

Materials and methods

Selection of plant species

From the Fabaceae family,some woody species having hard seed coats were selected,attesting to reported evidence of dif fi culties in obtaining adequate germination:R.pseudoacacia,A.dealbata,C.scoparius,C.multi fl orusandU.europaeus.

Black locust(R.pseudoacacia)is native to North America and planted for wood and energy purposes globally,generating biomass yields up to 14 Mg ha-1year-1(Pleguezuelo et al.2014;Straker et al.2015).It is also widely used in afforestation and soil restoration because of its ability to fi x nitrogen,tolerate stress,and sequester carbon.Moreover,the species is able to phytoremediate hydrocarbon-contaminated sites(Tischerand Hübner 2002)and bioaccumulate trace elements(Tzvetkova and Petkova 2015).It has been studied for the antioxidant potency of its fl owers(Sarikurkcu et al.2015).Silver wattle or mimosa(A.dealbata)is native to Australia and is also globally used for afforestation purposes,being a promising energy crop with low requirements and high productivity(Grif fi n et al.2011;Kull et al.2011).Because of mass winter fl owering and attractive foliage and form,it is used as a commercial garden and landscaping species,and the oil from its fl owers is used in the perfume industry(Grif fi n et al.2011;Kull et al.2011).This species has been also appraised for the production of chemicals,biofuels and pulp(Yáñez et al.2014;Pinto et al.2015).Otherwise,both legume species are highly invasive and are recognized as potential threats to natural ecosystems(Sheppard et al.2006;Lorenzo et al.2010;Richardson and Rejmánek 2011).

Scotch broom(C.scoparius)is widely distributed across Europe while white broom(C.multi fl orus)is endemic to the Iberian Peninsula.Gorse(U.europaeus)is a shrub native to the western coast of continental Europe and to the British Isles and a characteristic component of acid heathland vegetation.Lectins puri fi ed fromU.europaeusseeds are key tools for cancer research(Rüdiger and Gabius 2001)and the species has been satisfactorily evaluated as a possible source of xylans(Ligero et al.2011).In their native ranges,U.europaeusandC.scopariushave been traditionally used as a source of protein in animal food,and are highly valued for the rehabilitation of degraded soils(Pérez-Fernández et al.2016).Further,because of their worldwide use as ornamentals,these shrubby legumes have become critical invasive plants(Richardson and Hill.1998;Sheppard etal.2002;Richardson and Rejmánek 2011),and thus have received increased attention as sources of inexpensive biomass(Pérez et al.2014).For our experiments, fi eld collected seeds ofC.scoparius,C.multi fl orus,andU.europaeuswere purchased from the Zulueta Corporación(Navarra,Spain)whereas seeds ofR.pseudoacaciaandA.dealbatawere purchased from Semillas Montaraz,S.A.(Madrid,Spain),and stored at 4°C until used.

Experimental design

Seeds were subject to standardad hoctreatments to break dormancy and improve germination.Before the experiment,they were surface sterilized in 1% sodium hypochlorite for 5 min.to avoid surface fungi,and then thoroughly rinsed in distilled water.Seeds of the shrub species were subjected to three different physical treatments with reported ef fi cacy(Abdallah et al.1989;Tárrega et al.1992):the fi rst one consisted of soaking the seeds in boiling distilled water(100°C)for 5 min.In the second and third treatments,seeds were subjected to dry heat in an oven at 100 °C for 5 min.,or at 120 °C for 3 min.,respectively.Seeds of the tree species followed the supplier-recommended protocol,being immersed in boiling water and then quickly introduced to an ice bath.Moreover,seeds ofR.pseudoacaciawere previously soaked in distilled water for 48 h.In addition,seeds of all species were subjected to ourad hocmechanical treatment performed using a handheld rotary tool Ryobi®HT20VS(hereafter HRT),equipped with a sanding shank accessory of 13 mm×13 mm and an 80-grit sanding band.Seeds were deposited into a 100 mL glass beaker fi lled to one cm(Fig.1),and then subjected to the abrasive effect of the HRT(input power 100 W,no-load speed 6000 rpm)for 5 min.

For each treatment and species,twenty- fi ve seeds were placed in 9 cm Petri dishes with fi lter paper moistened with 5 mL of distilled water.Petri dishes were sealed with Para fi lm®to prevent evaporation and randomly placed in a growth chamber at 19 °C(±1 °C)in the dark,19 °C being the optimum germination temperature for many woody legumes(ISTA 1999).A total of 5 replicates per treatment and species were prepared.For each species, fi ve extra dishes containing the same number of untreated seeds were used as a control treatment.Germination(radicle protrusion of 1 mm,Mayer and Poljakoff-Mayber 1982)was recorded daily until no further visible radical emergence was observed.After 15 days,the total germination(Gt)percentage was calculated.Additionally,germination indices based on primary data were calculated(álvarez-Iglesias et al.2014)to determine the germination kinetics:speed of germination(S),speed of accumulated germination(AS),and the coef fi cient of the rate of germination(CRG),following Chiapusio et al.(1997)and De Bertoldi et al.(2009).

Fig.1 a Handheld rotary tool(HRT);b glass beaker fi lled with seeds and visual protocol of scari fi cation;c detail of the rotary head of the HRT equipped with the sanding shank accessory and the 80 grit sanding band

Statistics

Replicated experiments were disposed in a completely randomized design.Data were fi rst tested for normality by the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test and homogeneity of variances by Levene’s test.For each species,germination percentages(Gt)and germination indices were statistically analyzed by one-way ANOVA and LSD test for post hoc multiple comparisons when variances were homogeneous.In the case of heteroscedasticity,variance was analyzed by Kruskall–WallisHtest and Tamhane’sT2for post hoc multiple comparisons.All analyses were carried out using the IBM SPSS Statistics 19.0 software package(IBM SPSS Inc.,Chicago,IL,USA).

Results

The rotation of the HRT head over 5 min.produced a gradual warming due to the friction of the sanding band and the movement of the seeds.Temperatures measured inside the beaker rose from room temperature to 50°C(±5 °C).

Figure 2a shows the results of scari fi cation on the seeds of the shrub species.Only the HRT treatment was able to increase signi fi cantly the germination rates in comparison with the control.In theCytisusspecies,the application of HRT produced a conspicuous increase in Gtof 273%(P≤0.001)forC.scopariusand 175%(P≤0.001)forC.multi fl orus.No other method was effective to improve germination.Moreover,dry heat at 120°C completely impeded seed germination of the three shrub species,whereas germination was inhibited by boiling water to different degrees.

The results for the tree seeds are summarized in Fig.2b.Despite recommended scari fi cation methods were effective onR.pseudoacaciaandA.dealbata,the use of HRT achieved the best results,thus accomplishing Gtvalues over 90%(Fig.2b)for both species.Noteworthy,HRT enhanced seed germination ofA.dealbatafrom 3 to 98%(P≤0.001).

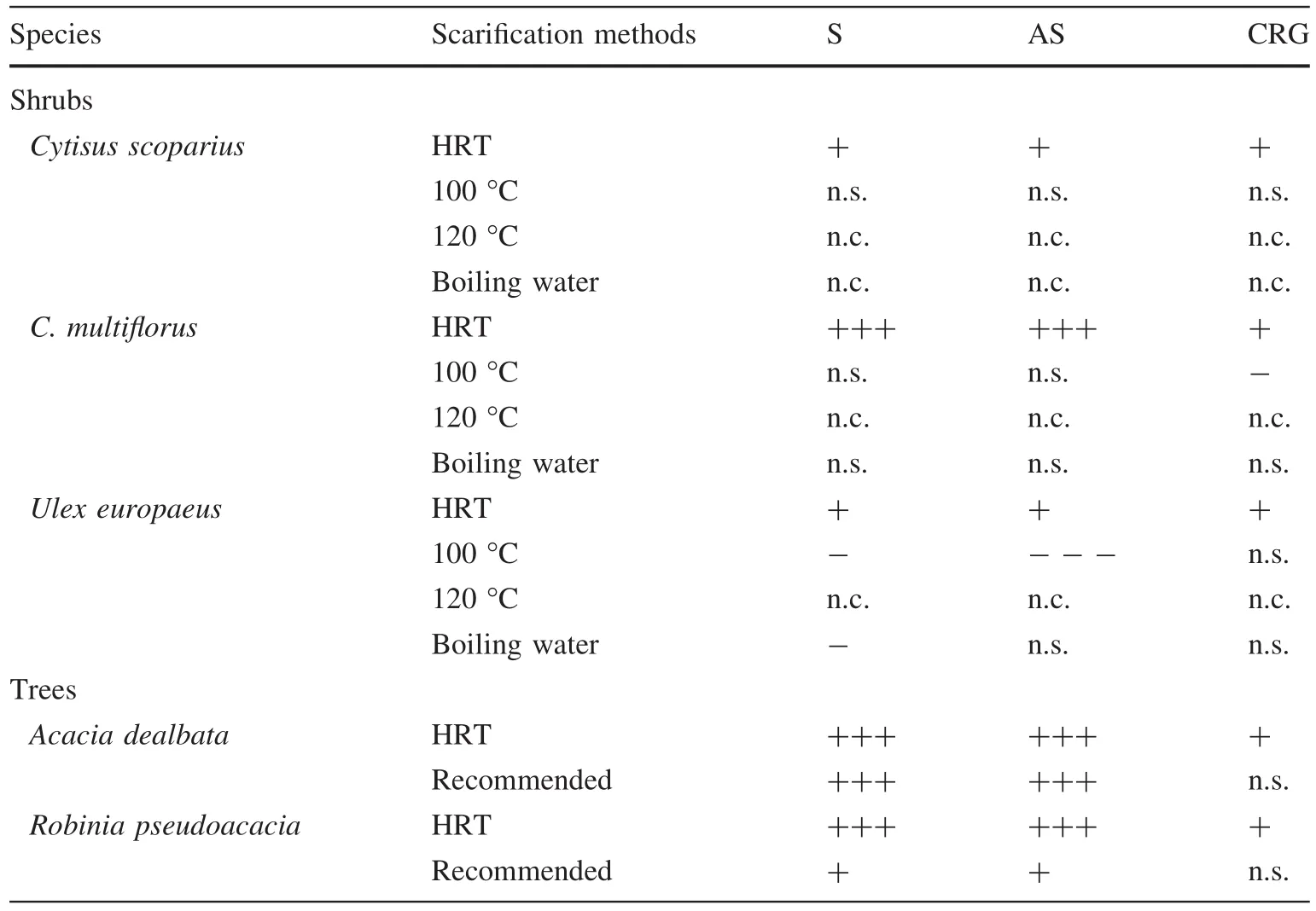

The complementary germination indices S,AS,CRG were calculated for rates above zero(Table 1),as their values are null when germination does not occur.Very similar results were obtained from S and AS indices,whereas CRG gave poorer information.The application of HRT was the only treatment that signi fi cantly increased the germination ofC.scoparius,C.multi fl orusandU.europaeus,whereas conventional treatments that allowed germination slowed down the germination speed.In the case ofR.pseudoacaciaandA.dealbata,both conventional and HRT treatments accelerated germination signi fi cantly.

Fig.2 Effects of different scari fi cation methods on seed germination of fi ve woody Fabaceae species:a shrubs and b trees.Asterisks indicate signi fi cant differences among treatments at***P≤0.001,**P ≤ 0.01,and*P ≤ 0.05(ANOVA or Kruskall–Wallis H).For each species,bars labelled with distinct letters are signi fi cantly different(P ≤ 0.05,LSD or Tamhane’s T2 test).Error bars represent SD.HRT,handheld rotary tool

Discussion

The rotary tool has been successfully evaluated by Cruz and de Carvalho(2006)and Dapont et al.(2014)for species ofSchizolobium,and forCuscutaspp.(Ghantous and Sandler 2012).To the best of our knowledge,this is the fi rst time that a handheld rotary tool has been used to disrupt dormancy inR.pseudoacacia,A.dealbata,C.scoparius,C.multi fl orusandU.europaeus.

As expected,germination rates of the selected species were low in the absence of any scari fi cation treatment.Shrub species showed a signi fi cant dependence on dormancy,with germination rates lower than 50%under all conventional treatments.Contrary to expectations,methods from the literature did not improve germination rates.High temperatures have been suggested as promoters of germination in selected species since seasonal fi res are a common phenomenon in Mediterranean-type ecosystems(Tárrega et al.1992;Sheppard et al.2006).Tárrega et al.(1992)obtained increased seed germination rates after the application of thermal treatments onC.scopariusseeds.Herranz et al.(1998),working with theCytisusgenus,found signi fi cant enhanced germination under mechanical or thermal scari fi cation treatments.Añorbe et al.(1990)also found positive effects of seed coat abrasion onC.multi fl orusgermination.In general,mechanical and thermal scari fi cation produced different effects on seed coat structures in species with hard coated seeds,causing differences in germination rates(Thanos et al.1992).Differential treatment effects could be linked with intraspeci fi c variations.In distinct ecotypes within the same species,natural variations in key regulatory genes resulting from selection during adaptation to speci fi c environments(among other cues and responses)may be operating,producing different degrees of dormancy(Finch-Savage and Leubner-Metzger 2006).Hanley(2009)found variable temperature responses byC.scopariusseeds dependant on their origin.Nonetheless,in our study we did not fi nd positive effects in comparison with controls after high temperature exposure;to the contrary,seed germination was inhibited at 120°C.Other authors have reported serious damage to seeds ofCytisussubjected to intense thermal shocks(Herranz et al.1998;Rivas et al.2006),whereas the lethal nature of temperatures over 100°C has been described forU.europaeus(Pereiras et al.1985).

Table 1 Effects of different scari fi cation methods on the germination indices of fi ve woody legume species compared to control

Besides dry heat,boiling water damagedC.scopariusseeds,impeding germination.Moreover,germination inC.multi fl orusandU.europaeuswas not signi fi cantly promoted by hot water compared to the controls.Previously,Herranz et al.(1998),working on theCytisusgenus found no signi fi cantdifferencesin germination afterseed immersion in boiling water,whereas Abdallah et al.(1989)reported an enhancement in the total germination ofC.scopariusseeds.Other authors indicated abnormal growth of herbaceous legumes after immersion in hot water(Mondoni et al.2013).Otherwise,R.pseudoacaciaandA.dealbataseed germinations were signi fi cantly enhanced after boiling water treatment,according to previous fi ndings(Toda and Ishikawa 1951;Doran 1986).Within the genusAcacia,different species have previously shown variable responses to the application of different scari fication methods,including boiling water,but also other techniques such as sulfuric acid and mechanical scari fi cation;in all cases,germination was enhanced in treated seeds(Ghassali et al.2012).Seeds ofAcaciashow poor germination in the absence of scari fi cation but have good tolerance to different treatments.Germination promoted by such a wide range of scari fi cation methods can in nature be translated as further opportunities to establish their seedlings(Watterson and Jones 2006).

The treatment imposed by the HRT,in comparison with conventional methods,was highly effective to overcome the‘block’imposed by seed dormancy in the evaluated species.In our opinion,the effectiveness of the HRT is due to the combined action of rapid mechanical abrasion and a gentle dry thermal scari fi cation.As the fi rst step of a proposed combined mode of action,sandpaper movement would diminish coat thickness,reducing mechanical constraints of the water-resistant cuticle(Dapont et al.2014),allowing the imbibition or absorption by the dry seed,the onset of gas exchange,and subsequently facilitate radicle protrusion.Secondly,the change of temperatures might affect both dormancy and germination.Temperature increases have been proposed to directly affect embryo development(i.e.,hypocotyl elongation),probably acting on breaking dormancy through alterations in ABA/GA synthesis and signalling pathway(Baskin and Baskin 2004;Stavang et al.2009;Smy kaletal.2014).Inourcase,thegentleandgradual rise in temperatures could have increased seed sensitivity to light(during the HRT treatment)and water(during imbibition),thus inducing improved germination.

It is worth emphasizing that our generalized and remarkable increase in germination percentages,together with the acceleration and standardization of emergence,are uncommon in scari fi cation treatments involving different genera and life forms.As a proposed mode of action of the HRT,we suggest a synergistic effect of mechanical scarifi cation and temperature in breaking seed dormancy and promoting radical emergence.Finch-Savage and Leubner-Metzger(2006),using a classi fi cation system based on the internal morphology of the embryo and endosperm in mature angiosperm seeds,assigned a combined dormancy—physical combined with physiological embryo dormancy—to members of the family Fabaceae.Thus,our method of scari fi cation with the HRT could have operated by concomitantly breaking the physical and physiological dormancy of the treated seeds.In our lab,the HRT failed to overcome deep seed dormancy inAilanthus altissimaandCrataegus monogyna,both belonging to phylogenetic groups lacking in combinational dormancy(Finch-Savage and Leubner-Metzger 2006).

A third factor is the effect of the centrifugal movement of seeds produced by the rotary head and their impact on the beaker wall.Some studies have indicated that percussion may be successfully used to ameliorate germination rates in legumes(Khadduri and Harrington 2002;Mondoni et al.2013).Amyloplasts—plastids that are responsible for the storage of starch—have been proposed to act as susceptors that sense mechanical vibrations inArabidopsis thaliana,increasing the rate of seed germination through the action of ethylene(Uchida and Yamamoto 2002).

Due to the obvious methodological constraints,classic scari fi cation methods such as the use of razor blades or sandpaperareconsideredhighlytime-consumingtreatments and not feasible for large quantities of seeds(Mondoni et al.2013).In response,the use of the HRT may save time and effort since a signi fi cant volume of seeds may be treated simultaneously.Nevertheless,a de fi nition of scari fi cation conditionsisrequiredsince,inspiteofthepositiveeffectson germination,damage to a major fraction of seeds may be in fl icted(Abdallah et al.1989).Ghassali et al.(2012)reported that the ef fi ciency of the HRT diminished as seed numbers increased.For a given type of dormancy(physical or combinational),the adequate number of seeds to scarify would depend on plant species,seed size and shape,and probably time of storage.The mandatory time of scari fi cation with different handheld rotary tools must be previously evaluated to avoid damage to the seed pool,especially when the number of available seed is limited.In our lab,optimal scari fi cation times for selected species,including the highly valued timber speciesAcacia melanoxylonR.Br.were evaluated with the HRT Dremel®3000(3000-15).Optimal germination rates forA.dealbataandA.melanoxylonwere obtained at 10,000–14,000 rpm for 10 min,applied in intervals of 3,3 and 4 min to avoid overheating.Otherwise,5 min was suf fi cient to achieve maximum Gtvalues forU.europaeusandC.scoparius.Asavisualtest,mostseedcoats showed yellow incisions of similar size after the different HRT treatments.These scari fi ed seeds were afterwards used in pot assays to evaluate the competitive abilities in multi speci fic mixtures(Pedrol et al.in prep.).Germinated seeds were viable and produced vigorous seedlings.Modi fi cations for temperature control could be possibly introduced to the commercial laboratory-scale seed scari fi ers in order to successfullyovercomecombinationaldormancyincertainhardcoated legume seeds.

Current laboratory and greenhouse experimentation,small-scale field trials,quality control in seed companies or seed banks,plant nurseries for afforestation,the timber and biomass industry,as well as revegetation programs,demand rapid,effective,low-cost and highly reproducible methods to break seed dormancy and to improve and synchronize germination.The results we present in this paper constitute evidence of the ef fi cacy and ef fi ciency of the handheld rotary tool for the scari fi cation of hard-coated seeds of several Fabaceae belonging to different genera:Robinia pseudoacacia,Acacia dealbata,A.melanoxylon,Cytisus scoparius,C.multi fl orusandUlex europaeus.We suggest a combined mode of action of the method on these species which could operate by concomitantly breaking the physical and physiological dormancy by abrasion of the hard seed coats and a gradual and gentle temperature rise.The method and the described features may contribute to developing prototypes for overcoming combinational seed dormancy of these and other species.

AcknowledgementsWe wish to thank the patience of Carlos Bolaño(‘our’dear Lab Technician)during artwork elaboration(and every time),and Esther Pájaro and Iria Rodríguez-Alén for their welcome hands-on assistance.

Abdallah MM,Jones RA,El-Beltagy AS(1989)A method to overcome dormancy in Scotch broom(Cytisus scoparius).Environ Exp Bot 29(4):499–505

Abudureheman B,Liu HL,Zhang DY,Guan K(2014)Identi fi cation of physical dormancy and dormancy release patterns in several species(Fabaceae)of the cold desert,north-west China.Seed Sci Res 24(2):133–145

álvarez-Iglesias L,Puig CG,Garabatos A,Reigosa MJ,Pedrol N(2014)Vicia fabaaqueous extracts and plant material can suppress weeds and enhance crops.Allelopathy J 34(2):299–314

Añorbe M,Gómez Gutiérrez JM,Pérez Fernández MA,Fernández Santos B(1990)In fl uence of temperature on seed germination ofCytisus multi fl orus(L Hér.)andCytisus oromediterraneusRiv.Mar.,in Spanish.Stvdia Oecol 7(1):85–100

Baskin JM,Baskin CC(2004)A classi fi cation system for seed dormancy.Seed Sci Res 14(1):1–16

Bentsink L,Hanson J,Hanhart CJ,Blankestijn-De Vries H,Coltrane C,Keizer P,El-Lithy M,Alonso-Blanco C,De Andrés MT,Reymond M,Van Eeuwijk F,Smeekens S,Koornneef M(2010)Natural variation for seed dormancy inArabidopsisis regulated by additive genetic and molecular pathways.Proc Natl Acad Sci 107(9):4264–4269

Bewley JD(1997)Seed germination and dormancy.Plant Cell 9(7):1055–1066

Bradshaw A(1997)Restoration of mine lands using natural processes.Ecol Eng 8(4):255–269

Chaer GM,Resende AS,Campello EFC,de Faria SM,Boddey RM(2011)Nitrogen- fi xing legume tree species for the reclamation of severely degraded lands in Brazil. Tree Physiol 31(2):139–149

Chiapusio G,Sánchez AM,Reigosa MJ,González L,Pellissier F(1997)Do germination indices adequately re fl ect allelochemical effects on the germination process? J Chem Ecol 23(11):2445–2454

Cruz ED,de Carvalho JEU(2006)Methods of overcoming dormancy inSchizolobium amazonicumHuber ex Ducke(Leguminosae–Caesalpinioideae)seeds,in Portuguese.Rev Bras Sementes 28(3):108–115

Dapont EC,Silva JBD,Oliveira JDD,Alves CZ,Dutra AS(2014)Methods of accelerating and standardising the emergence of seedlings inSchizolobium amazonicum.Rev Cienc Agron 45(3):598–605

De Bertoldi C,De Leo M,Braca A,Ercoli L(2009)Bioassay-guided isolation of allelochemicals fromAvena sativaL.:allelopathic potential of fl avone C-glycosides.Chemoecology 19(3):169–176

Doran JC(1986)Seed,nursery practice and establishment.In:Brown AG,Boland DJ,Doran JC,Martensz PN,Hall N(eds)Multipurpose Australian trees and shrubs.Lesser-known species for fuel wood and agroforestry.ACIAR,Canberra,pp 1–29

Finch-Savage WE,Leubner-Metzger G(2006)Seed dormancy and the control of germination.New Phytol 171(3):501–523

Ghantous KM,Sandler HA(2012)Mechanical scari fi cation of dodder seeds with handheld rotary tool.Weed Technol 26(3):485–489

Ghassali F,Salkini AK,Petersen SL,Niane AA,Louhaichi M(2012)Germination dynamics ofAcaciaspecies under different seed treatments.Range Manag Agrofor 33(1):37–42

Grif fi n AR,Midgley SJ,Bush D,Cunningham PJ,Rinaudo AT(2011)Global uses of Australian acacias—recent trends and future prospects.Divers Distrib 17(5):837–847

Hanley ME(2009)Thermal shock and germination in North-West European Genisteae:implications for heathland management and invasive weed controlusing fi re.ApplVeg Sci 12(3):385–390

Herranz JM,Ferrandis P,Martínez Sánchez JJ(1998)In fl uence of heat on seed germination of seven Mediterranean Leguminosae species.Plant Ecol 136(1):95–103

ISTA,International Seed Testing Association(1999)International rules for seed testing.Seed Sci Technol 27(Suppl.):1–333

Janzen DH(1981)Enterolobium cyclocarpumseed passage rate and survival in horses,Costa Rican pleistocene seed dispersal agents.Ecology 62(3):593–601

Kelly KM,Van Staden J,Bell WE(1992)Seed coat structure and dormancy.Plant Growth Regul 11(3):201–209

Khadduri NY,Harrington JT(2002)Shaken,not stirred–a percussion scari fi cation technique.Native Plants J 3(1):65–66

Koornneef M,Bentsink L,Hilhorst H(2002)Seed dormancy and germination.Curr Opin Plant Biol 5(1):33–36

Kull CA,Shackleton CM,Cunningham PJ,Ducatillon C,Dufour-Dror JM,Esler KJ,Zylstra MJ(2011)Adoption,use and perception of Australian acacias around the world.Divers Distrib 17(5):822–836

Ligero P,de Vega A,van der Kolk JC,van Dam JEG(2011)Gorse(Ulex europæus)as a possible source of xylans by hydrothermal treatment.Ind Crops Prod 33(1):205–210

Linkies A,Graeber K,Knight C,Leubner-Metzger G(2010)The evolution of seeds.New Phytol 186(4):817–831

Lorenzo P,González L,Reigosa MJ(2010)The genusAcaciaas invader:the characteristic case ofAcacia dealbataLink in Europe.Ann For Sci 67(1):1–11

Mayer AM,Poljakoff-Mayber A(1982)The germination of seeds.Pergamon,London

Mondoni A,Tazzari ER,Zubani L,Orsenigo S,Rossi G(2013)Percussion as an effective seed treatment for herbaceous legumes(Fabaceae):implications for habitat restoration and agriculture.Seed Sci Technol 41(2):175–187

Nongrum A,Kharlukhi L(2013)Effect of seed treatment for laboratory germination ofAlbiziachinensis.J ForRes 24(4):709–713

Patane`C,Gresta F(2006)Germination ofAstragalus hamosusandMedicago orbicularisas affected by seed-coat dormancy breaking techniques.J Arid Environ 67(1):165–173

Peinetti R,Pereyra M,Kin A,Sosa A(1993)Effects of cattle ingestion on viability and germination rate of caldén(Prosopis caldenia)seeds.J Range Manag 46(6):483–486

Pereiras J,Puentes MA,Casal M(1985)Effect of high temperatures on gorse(Ulex europaeusL.)seed germination/Efecto de las altas temperaturas sobre la germinación de las semillas del tojo(Ulex europaeusL.),in Spanish.Stvdia Oecol 6:125–133

Pérez S,Renedo CJ,Ortiz A,Delgado F,Fernández I(2014)Energy potential of native shrub species in northern Spain.Renew Energy 62:79–83

Pérez-Fernández MA,Calvo-Magro E,Valentine A(2016)Bene fi ts of the symbiotic association of shrubby legumes for the rehabilitation of degraded soils under Mediterranean climatic conditions.Land Degrad Dev 27(2):395–405

Pinto PC,Oliveira C,Costa CA,Gaspar A,Faria T,Ataíde J,Rodrigues AE(2015)Kraft deligni fi cation of energy crops in view of pulp production and lignin valorization.Ind Crops Prod 71:153–162

PleguezueloCRR,ZuazoVHD,BieldersC,BocanegraJAJ,PereaTorres F,Martínez JRF(2014)Bioenergy farming using woody crops.A review.Agron Sustain Dev 35(1):95–119

Richardson RG,Hill RL(1998)The biology of Australian weeds 34.Ulex europaeusL.Plant Prot Q 13(2):46–58

Richardson DM,Rejmánek M(2011)Trees and shrubs as invasive alien species—a global review.Divers Distrib 17(5):788–809

Rivas M,Reyes O,Casal M(2006)In fl uence of heat and smoke treatments on the germination of six leguminous shrubby species.Int J Wildland Fire 15(1):73–80

Rüdiger H,Gabius HJ(2001)Plant lectins:occurrence,biochemistry,functions and applications.Glycoconj J 18(8):589–613

Sarikurkcu C,Kocak MS,Tepe B,Uren MC(2015)An alternative antioxidative and enzyme inhibitory agent from Turkey:Robinia pseudoacaciaL.Ind Crops Prod 78:110–115

Sheppard AW,Hodge P,Paynter Q,Rees M(2002)Factors affecting invasion and persistence of broomCytisus scopariusin Australia.J Appl Ecol 39(5):721–734

Sheppard AW,Shaw RH,Sforza R(2006)Top 20 environmental weeds for classical biological control in Europe:a review of opportunities,regulations and other barriers to adoption.Weed Res 46(2):93–117

Smy kal P,Vernoud V,Blair MW,Soukup A,Thompson RD(2014)The role of the testa during development and in establishment of dormancy of the legume seed.Front Plant Sci 5:1–19

Stavang JA,Gallego-BartoloméJ,Gómez MD,Yoshida S,Asami T,Olsen JE,García-Martínez JL,AlabadíD,Blázquez MA(2009)Hormonal regulation of temperature—induced growth inArabidopsis.Plant J 60(4):589–601

Straker KC,Quinn LD,Voigt TB,Lee DK,Kling GJ(2015)Black locust as a bionergy feedstock:a review.BioEnergy Res 8(3):1117–1135

Sy A,Grouzis M,Danthu P(2001)Seed germination of seven Sahelian legume species.J Arid Environ 49(4):875–882

Tárrega R,Calvo L,Trabaud L(1992)Effect of high temperatures on seedgermination oftwowoody Leguminosae.Vegetatio 102(2):139–147

Teketay D(1996)Germination ecology of twelve indigenous and eight exotic multipurpose leguminous species from Ethiopia.For Ecol Manag 80(1):209–223

Thanos CA,Georghiou K,Kadis C,Pantazi C(1992)Cistaceae:a plant family with hard seeds.Isr J Bot 41(4–6):251–263

Tigabu M,Oden PC(2001)Effect of scari fi cation,gibberellic acid and temperature on seed germination of two multipurposeAlbiziaspecies from Ethiopia.Seed Sci Technol 29(1):11–20

Tischer S,Hübner T(2002)Model trials for phytoremediation of hydrocarbon-contaminated sites by the use of different plant species.Int J Phytorem 4(3):187–203

Toda R,Ishikawa H(1951)Hasting the germination ofRobiniaseeds by the use of boiling water.J Jpn For Soc 33(9):312

Twigg LE,Lowe TJ,Taylor CM,Calver MC,Martin GR,Stevenson C,How R(2009)The potential of seed—eating birds to spread viable seeds of weeds and other undesirable plants.Austral Ecol 34(7):805–820

Tzvetkova N,Petkova K(2015)Bioaccumulation of heavy metals by the leaves ofRobinia pseudoacaciaas a bioindicator tree in industrial zones.J Environ Biol 36(1):59–63

Uchida A,Yamamoto KT(2002)Effects of mechanical vibration on seed germination ofArabidopsis thaliana(L.)Heynh.Plant Cell Physiol 43(6):647–651

Vilela AE,Ravetta DA(2001)The effect of seed scari fi cation and soil-media on germination,growth,storage,and survival of seedlings of fi ve species ofProsopisL.(Mimosaceae).J Arid Environ 48(2):171–184

Wali MK(1999)Ecological succession and the rehabilitation of disturbed terrestrial ecosystems.Plant Soil 213(1–2):195–220

Watterson NA,Jones JA(2006)Flood and debris fl ow interactions with roads promote the invasion of exotic plants along steep mountain streams, western Oregon. Geomorphology 78(1):107–123

Yáñez R,Gómez B,Martínez M,Gullón B,Alonso JL(2014)Valorization of an invasive woody species,Acacia dealbata,by means of Ionic liquid pretreatment and enzymatic hydrolysis.J Chem Technol Biotechnol 89(9):1337–1343

Zare S,Tavili A,Darini MJ(2011)Effects of different treatments on seed germination and breaking seed dormancy ofProsopis koelzianaandProsopis juli fl ora.J For Res 22(1):35–38

Journal of Forestry Research2018年2期

Journal of Forestry Research2018年2期

- Journal of Forestry Research的其它文章

- Effect of species composition on ecosystem services in European boreal forest

- Analysis of SSR loci and development of SSR primers in Eucalyptus

- Genetic effects of historical anthropogenic disturbance on a longlived endangered tropical tree Vatica mangachapoi

- Genetic variation in relation to adaptability of three mangrove species from the Indian Sundarbans assessed with RAPD and ISSR markers

- Cloning and characterization of geranylgeranyl diphosphate synthetase from Pinus massoniana and its correlation with resin productivity

- In vitro anther culture and Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of the AP1 gene from Salix integra Linn.in haploid poplar(Populus simonii×P.nigra)