基于野外观察的黑颈鹤个体行为谱构建

韩雪松 郭玉民

(北京林业大学自然保护区学院,北京,100083)

行为是鸟类的固有特征之一,鸟类的生存需求通过不同的行为表达来实现[1]。依照行为发生的动机和作用的对象,鸟类行为可以分作个体行为(Individual Behavior,or Non-Social Behavior)及社会行为(Social Behavior)。其中,个体行为是构成鸟类一切行为的基本要素,亦是其行为的最关键组成部分[2]。个体行为在不同情景下或具有社会性的含义而同社会行为的界限并不清晰,有时亦作为复杂社会行为的一部分而出现[3]。因此,对于鸟类个体行为的描述是研究其复杂行为序列、社会行为乃至更深层次的行为机理的基础,对其了解的程度将影响对其的研究以及保护工作的成效[4]。

鹤形目(Gruiformes)鸟类是古老的动物类群[5],对其的行为学研究已有很多工作付诸实践[6-10]。作为随青藏高原隆起而形成的特有物种,黑颈鹤(Grusnigricollis)是鹤科(Gruidae)当中适应于高原严酷自然环境的独特一支[11-12]。在黑颈鹤的行为学研究上,目前已有工作多局限于行为描述及时间分配等方面[13-28],而对个体行为——特别是其分级分类——并未得到充分的探索,仅有的研究也局限于笼养个体[3,17]。系统的个体行为分类体系的缺乏导致已有行为学研究无法基于共同标准进行,而对于特定行为界定的模糊进一步导致对其结果无法比较,严重影响了对于黑颈鹤行为学研究的进展。

基于此,本文通过对于黑颈鹤的野外观察来完成黑颈鹤个体行为的描述及行为谱的绘制,旨在提出黑颈鹤的个体行为分类体系,以为更深层次的黑颈鹤行为研究提供基础。

1 研究方法

1.1 野外工作及数据采集

在越冬地,野外工作分别在2012年1月、2013年3月、2014年3月开展于云南昭通大山包和贵州威宁草海,在繁殖地分别在2013年4~6月、2014年4~7月开展于甘肃、青海、四川以及西藏的黑颈鹤繁殖栖息地。野外工作中,除直接观察外,同时使用摄影摄像设备(Canon 7D & Canon 400 mm F5.6)来对黑颈鹤的行为进行记录。最终,共获得有效视频文件约8 930 min,有效照片63 200余张。基于以上材料,本文对黑颈鹤在野外条件下的个体行为进行分类、描述,并在Adobe Illustrator CC当中完成行为谱的绘制。

1.2 行为分类系统及术语

在对黑颈鹤的个体行为进行分类时,主要参考由Ellis et al.(1991)提出并由Masatomi(2004)完善的鹤类个体行为分类体系,其为鹤类个体行为提供了一套科学的、标准化的框架[3-4];在对行为进行描述时,主要参考Masatomi and Kitagawa(1975),其以丹顶鹤(Grusjaponensis)为例对鹤类行为描述中提供了一套基于形态学特征的准则[9]。本研究中新记录到的行为在命名时基于Ellis et al.(1991)提出的命名法[3],并在文中以下划线标出。对于部分行为(出现次数n<100),除完成行为的描述和行为谱的绘制外,还对其发生的次数和持续的时间加以统计,而频繁出现的行为(n≥100)则不做统计[4]。为减少不必要的误解,本行为谱中所列行为均为在野外有过观察和记录的,对于其他列入Ellis et al.(1991)、Masatomi(2004)行为分类系统但于黑颈鹤上尚未在野外观察到且未见报道的行为不予记录[3-4]。

2 结果与分析

基于静息姿态,黑颈鹤的个体行为可以被划分为:Ⅰ.休憩行为,Ⅱ.感知行为,Ⅲ.保养行为,Ⅳ.运动行为,Ⅴ.摄食、排遗和排泄。

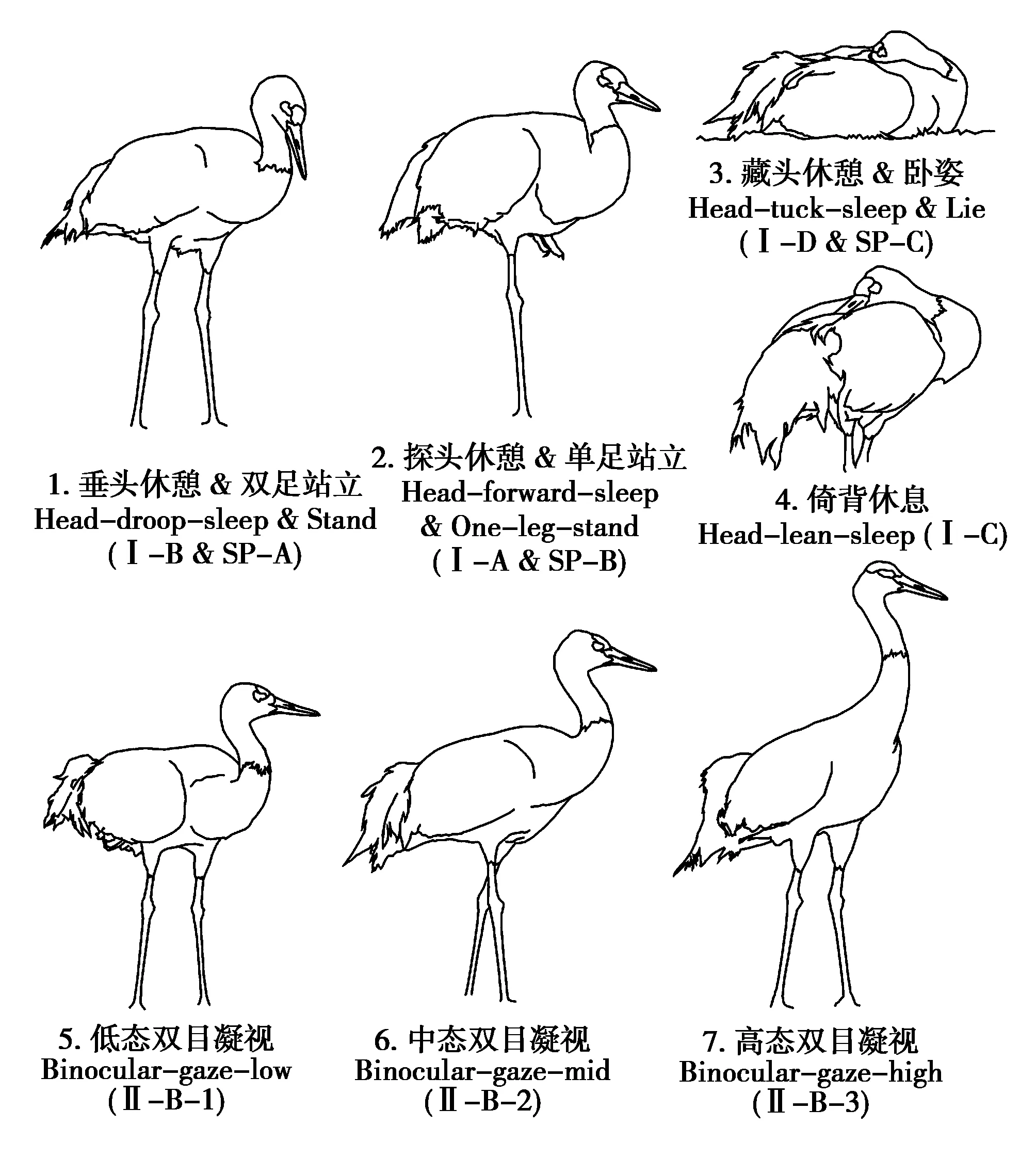

SP-静息姿态Still PosturesSP-A.双足站立Stand(图 1-1.)

双腿直立支撑身体。长时间站立时,两腿常平行;若为行进中暂停,双腿则或交叉。

SP-B.单足站立One-leg-stand(图 1-2.)

身体由一腿支撑,另一腿或收回腹部,或贴合腹部,或自然悬垂。当个体采单腿站立时,为保持重心,支撑腿略向外倾斜。

SP-C.卧姿Lie(图 1-3.)

双腿折叠于躯干下。在越冬地觅食后的下午,黑颈鹤常以此方式在草地上进行休息,而在繁殖地仅有1次记录(非孵化)。

Ⅰ-休憩行为Sleep-related BehaviorⅠ-A.探头休憩Head-forward-sleep(图 1-2.)

躯干水平,颈部收缩,头部自然指向前方,喙部微向下指,双眼闭合(n>100)。

Ⅰ-B.垂头休憩Head-droop-sleep(图 1-1.)

类似于探头休憩,但头部自然下垂,颌部倚靠在颈部进行休息(n>100)。

Ⅰ-C.倚背休憩Head-lean-sleep(图 1-4.)

躯干略后倾,两翼微微上抬,颈部由一侧向后弯曲,头部前伸倚靠在背部进行休息(n>100)。

Ⅰ-D.藏头休憩Head-tuck-sleep(图 1-3.)

类似倚背休憩,但喙部插入背部覆羽当中。在观察中发现,眼睛虽然闭合但始终暴露在外,一旦出现干扰,其眼睛会迅速睁开,并抽出头部进行警戒(n>100)。

图1 静息姿态,休憩行为以及感知行为Fig.1 Still posture,sleep-related behavior and sensory-related behavior

Ⅱ-感知行为Sensory-related BehaviorⅡ-A.观察Observe

往往同黑颈鹤其他行为同时进行,抑或构成其其他行为序列的部分。例如,觅食过程中搜寻食物,行进或飞行过程中察看前方的情况等。在进行观察时,个体往往较放松,表现为体羽不蓬松,头部裸皮不充血(n>100)。

Ⅱ-B.警戒Vigilance

在警戒时,由于干扰的存在,个体往往较为紧张,表现为体羽蓬松,头部裸皮充血,步态局促等。警戒行为的程度可以很好地通过头颈部的动作来进行表征。

Ⅱ-B-1.低态双目凝视Binocular-gaze-low(图 1-5.)

躯干水平,颈部向上,头部指向干扰来源,此时颈部仍较弯曲(n>100)。

Ⅱ-B-2.中态双目凝视Binocular-gaze-mid(图 1-6.)

躯干略后倾,颈部上抬但仍然弯曲(n>100)。

Ⅱ-B-3.高态双目凝视Binocular-gaze-high(图 1-7.)

躯干后倾,颈部极度伸直,头顶裸皮完全张开,注视干扰来源,之后往往紧随以踱步、鸣叫等行为(n>100)。

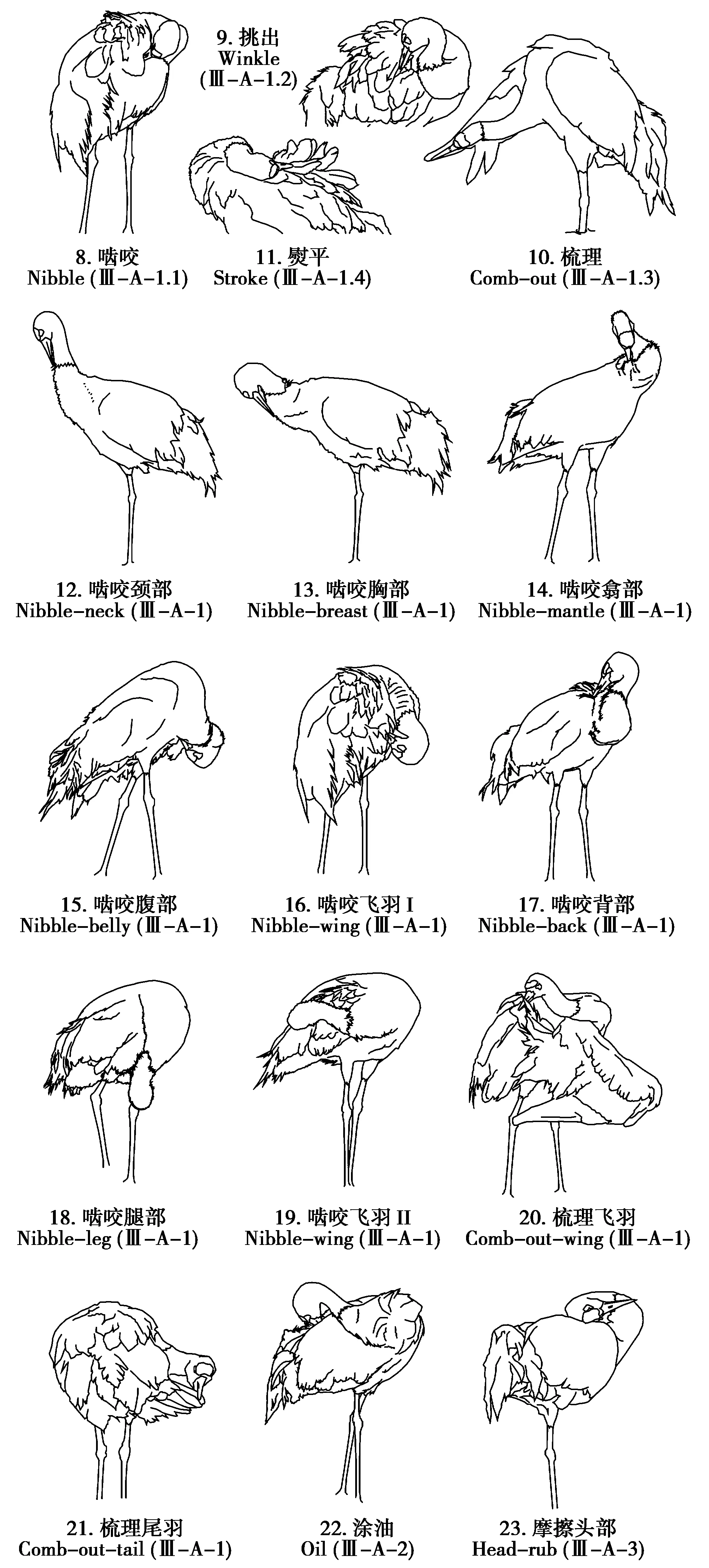

Ⅲ-保养行为Maintenance BehaviorⅢ-A.体表保养Care of body surfaceⅢ-A-1.理羽Preen

理羽是由一系列旨在清洁羽毛上黏附的异物、去除体表的寄生虫、分开纠结缠绕的羽枝、理顺羽毛的方向和促进羽毛的更换等行为构成。理羽行为可出现在3种静息姿势下,且会因清洁身体不同部分的需要而以不同的形态表达,部分典型理羽行为见图 2-12~21。按照梳理羽毛的动作,理羽行为可以分作:

Ⅲ-A-1.1.啮咬Nibble(图 2-8.)

喙插入羽毛着生部,小幅开合,快速啮咬羽毛根部及附近表皮。在此过程中,喙的啮咬由一个部位迅速转移至与其相邻的另一个部位,不作大幅划动(n>100)。

Ⅲ-A-1.2.挑出Winkle(图 2-9.)

常见于雪夜后的清晨,其目的在于分开纠结缠绕在一起的羽毛。喙部深插入体羽(特别是背部覆羽中),而后自体表迅速向外挑出,挑出幅度由所打理羽毛的长度决定,往往止于羽端,但因惯性会多划出一段距离。挑出的方向则是由受处理羽区羽毛的着生方向和身体——尤其是头颈的生理结构来共同决定(n>100)。

图2 保养行为(Ⅲ-A-1~3)Fig.2 Maintenance behavior(Ⅲ-A-1~3)

Ⅲ-A-1.3.梳理Comb-out(图 2-10.)

常见于清洗身体后个体对初级飞羽及尾羽的清理中。喙部轻咬住尾羽或初级飞羽根部自羽根沿羽干向外捋动,以除去蓄积在羽毛中的水分或悬坠于飞羽端部的冰块——对于后者而言,喙部开合的幅度恰小于冰块的宽度而大于羽毛的厚度(n>100)。

Ⅲ-A-1.4.熨平Stroke(图 2-11.)

颈部弯向一侧,以头部裸皮压向体表,随后边挥动喙部边将头部在整个背部往复碾动扫动。此行为目的在于压平被风吹起的羽毛(n>100)。

Ⅲ-A-2.涂油Oil(图 2-22.)

头部由体侧探向体后,该侧翼同时轻垂,喙部探向尾脂腺,同时尾亦转向同侧接近。喙部拨开尾脂腺上方的羽毛后在腺体上滑动,通过圆形摩擦运动使得头侧亦沾满油脂。随后,通过上述不同的理羽行为,个体将尾脂涂满全身(n=19)。

Ⅲ-A-3.摩擦头部Head-rub(图 2-23)

类似于理羽行为中的熨平,但头部仅在翕部及肩部碾动摩擦,喙部亦出离体羽,旨在解除头顶裸皮瘙痒(~4.98 s,n=6)。

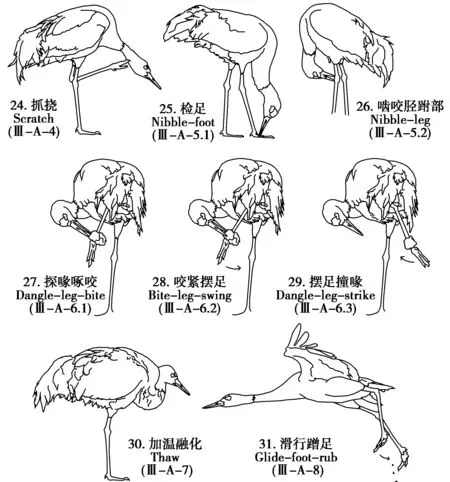

Ⅲ-A-4.抓挠Scratch(图 3-24.)

该行为可分为头部抓挠(Head-scratch)和颈部抓挠(Neck-scratch)[4],但二者常相继发生。单足或双足站立,躯干略后倾,颈部斜向下指,头部直伸。一侧腿抬起,以中趾抓挠头颈,期间头颈亦转动以配合足趾抓挠(~7.93 s,n=22)。其后往往紧随以摆头或俯身抻颈抖动的行为。

Ⅲ-A-5.啮咬表皮Nibble-integuments

李筑眉等(2005)首先在黑颈鹤上报道[29],基于啮咬部位的不同可分为:

图3 保养行为(Ⅲ-A-4~8)Fig.3 Maintenance behavior(Ⅲ-A-4~8)

Ⅲ-A-5.1.检足Nibble-foot(图 3-25.)

双足站立,颈部下弯,头部向下,喙部探向足趾进行啮咬(n=11)。

Ⅲ-A-5.2.啮咬胫跗部Nibble-leg(图 3-26.)

类似前者,但俯身啮咬胫跗部(n=8)。

Ⅲ-A-6.俯身啄除Dangle-leg-care

单足站立,躯干保持水平,头颈由足趾抬起一侧后弯,以去除附着在跗蹠部的异物,如冰块、黏土等,持续时间因附着物不同而异。

Ⅲ-A-6.1.探喙啄咬Dangle-leg-bite(图 3-27.)

通过喙部对异物进行咬啄(n=5)。

Ⅲ-A-6.2.咬紧摆足Bite-leg-swing(图 3-28.)

喙端咬紧附着物之后,该侧腿向后缓慢蹬踹(n=1)。

Ⅲ-A-6.3.摆足撞喙Dangle-leg-strike(图 3-29.)

头颈固定,抬起的跗蹠部向前摆动,使其上的凝着物反复撞击喙部(n=1)。

Ⅲ-A-7.加温融化Thaw(图 3-30.)

见于越冬地的黑颈鹤处理凝结在其跗蹠部的镯状冰块。单腿站立,期间亦会表现有理羽等行为,但腿部几乎完全为腹部覆羽所覆盖以为其加温。在野外观察中即记录到:黑颈鹤在反复顿足、啄咬无效后将其收于腹下,一段时间后再度啄咬,如此往复共加温7 min 20 s,最终将其去除(n=1)。

Ⅲ-A-8.滑行蹭足Glide-foot-rub(图 3-31.)

动作类似于垂腿飞行。双腿垂下,污染腿保持静止,另一腿反复屈伸、上下,以进行摩擦及拍打。见于在飞行中黑颈鹤除去黏在足趾间的大块泥巴(n=1)。

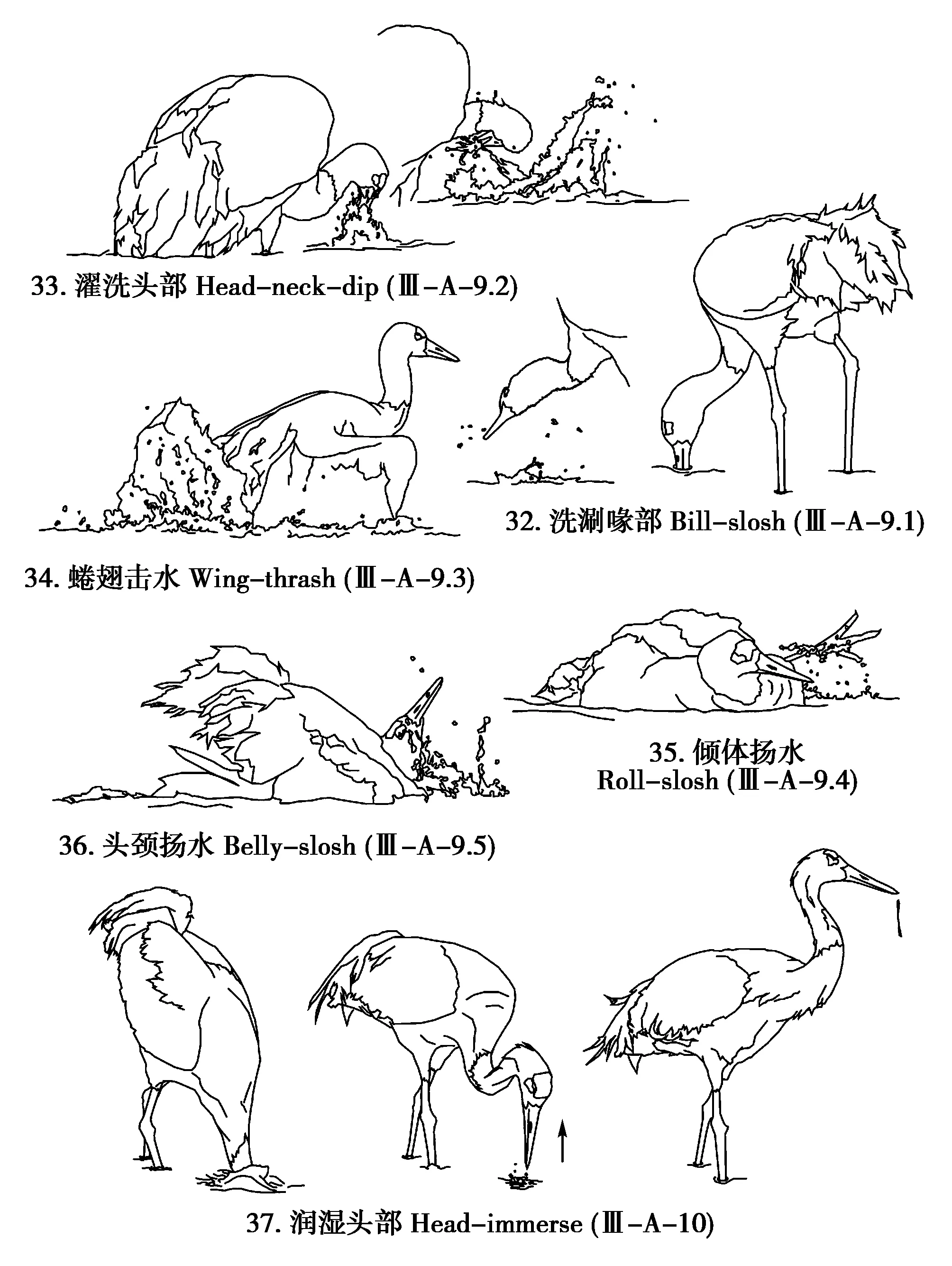

Ⅲ-A-9.清洗身体Bathe

在黑颈鹤清洗身体过程中共记录到5种行为,其有可能单独或组合出现:

Ⅲ-A-9.1.洗涮喙部Bill-slosh(图 4-32.)

双足站立,躯干略前倾,头颈近乎垂直扎入水面,喙部入水即上扬。头部在扬起时或扬起后快速横向甩动,持续约0.74 s(n=24)。

Ⅲ-A-9.2.濯洗头部Head-neck-dip(图 4-33.)

双足站立,躯干轻微或极度前倾(取决于其站于水中或岸边),颈部快速直伸下摆,头部垂直入水,之后立即快速旋转抬起,有时反复多次(~2.69 s,n=21)。

Ⅲ-A-9.3.蜷翅击水Wing-thrash(图 4-34.)

腿部弯曲身体浮于水中,两翼部分打开并反复剧烈拍击水面,同时躯干后部及尾亦剧烈起伏(~2.52 s,n=13)。

Ⅲ-A-9.4.倾体扬水Roll-slosh(图 4-35.)

腿部弯曲身体浸于水中,一腿斜向后上方扬出水面,同时躯干向对侧扭转约45°,头颈就势浸入水中(~2.24 s,n=8)。

Ⅲ-A-9.5.头颈扬水Belly-slosh(图 4-36.)

躯干前倾使胸部浸入水中,头颈迅速下压,喙部直击水面,入水后头部随即转向一侧扬出,以将水撩至背部(~3.55 s,n=11)。

图4 保养行为(Ⅲ-A-9~10)Fig.4 Maintenance behavior(Ⅲ-A-9~10)

Ⅲ-A-10.润湿头部Head-immerse(图 4-37.)

双足站立,颈部向下摆动,头部慢速垂直插入水中至完全湿润——以此区别于洗漱喙部;头部入水后,颈部即行上摆,头部保持垂直角度脱离水体——以此区别于饮水行为;期间未见有任何甩动头颈动作——以此区别于濯洗头部;颈部上扬至头部脱离水体后复向下插入,反复多次,喙部指向同一位置——以此区别于水中俯身啄刺。仅在繁殖期蚊虫密布的觅食地记录到1次(n=1),在记录到的视频影像中可清晰地分辨出镜头前大群蚊虫似烟雾状,据此推测黑颈鹤意在藉由水流驱避蚊虫,解除搔痒,保护不覆羽的头部裸皮。

Ⅲ-A-11.垂翼Wing-droop

双足站立,一侧翼或两侧翼初级飞羽垂下,仅见于洗澡后晾干飞羽(n=2)。

Ⅲ-B.抖动ShakeⅢ-B-1.甩喙Bill-flick

类似于洗漱喙部,但喙并不沾湿,仅通过甩动去除喙部黏附污物(~0.27 s,n=43)。

Ⅲ-B-2.摆头Head-shake(图 5-38.)

双足站立,颈部向上,头部横向快速反复甩动(~0.56 s,n=36)。

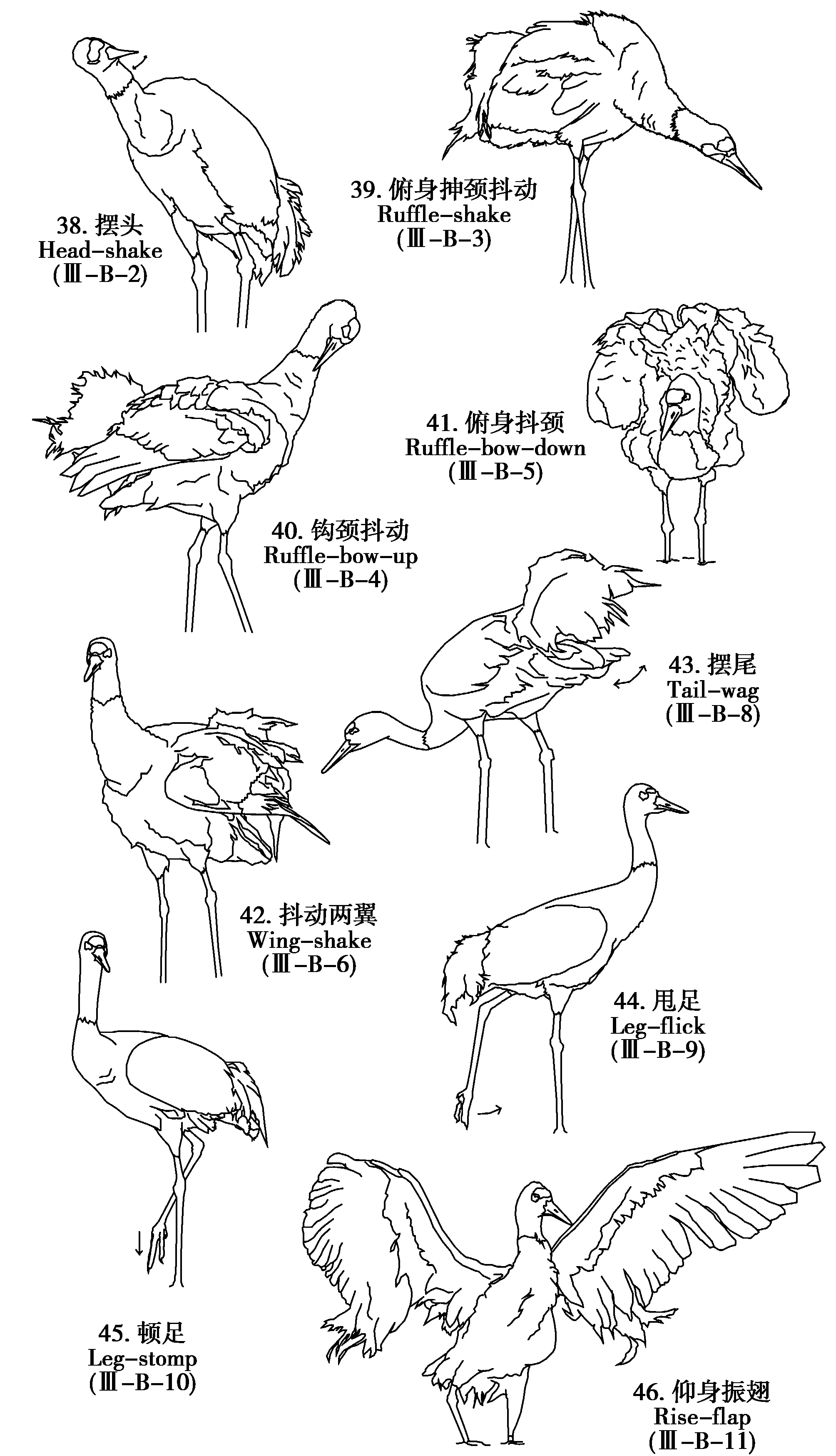

图5 保养行为(Ⅲ-B-2~11)Fig.5 Maintenance behavior(Ⅲ-B-2~11)

Ⅲ-B-3.俯身抻颈抖动Ruffle-shake(图 5-39.)

双足站立,躯干略前倾,两翼轻离躯干,颈部首先稍作收缩而后迅速向斜下旋转刺出(~1.50 s,n=29)。

Ⅲ-B-4.钩颈抖动Ruffle-bow-up(图 5-40.)

双足站立,颈部向上直伸,头部向下钩回,喙部贴压颌下覆羽。躯干快速抖动,同时两翼及尾羽明显出离躯干(~2.53 s,n=17)。

Ⅲ-B-5.俯身抖颈Ruffle-bow-down(图 5-41.)

双足站立,躯干前倾,颈部弯曲而贴合躯干,两翼向外部分打开,快速抖动,其间可见羽毛明显蓬起(~2.78 s,n=3)。

Ⅲ-B-6.抖动两翼Wing-shake(图 5-42.)

双足站立,躯干略后倾而颈部略弯曲,两翼快速抖动并轮流拍打身体(~1.24 s,n=31)。其后常紧随以俯身抻颈抖动或提翅。

Ⅲ-B-7.提翅Wing-fold

常作为降落、抖动或伸展后的调整动作出现,也见于觅食过程的行走中。两翼初级飞羽几乎同时上提并自然贴合躯干(~0.19 s,n=57)。

Ⅲ-B-8.摆尾Tail-wag(图 5-43.)

双足站立,躯干前倾,三级飞羽微微耸起,露出短小的尾羽。尾羽首先伸张,继而快速左右摆动(~1.03 s,n=69)。

Ⅲ-B-9.甩足Leg-flick(图 5-44.)

单足站立,躯干略前倾,悬垂腿胫跗部向后紧贴腹部,跗蹠部反复向后作蹬踹动作(~2.76 s,n=33)。

Ⅲ-B-10.顿足Leg-stomp(图 5-45.)

见于跗蹠部凝着有较大冰块或其足趾部黏带有成块的泥巴。类似于甩足,但跗蹠部迅速垂直下摆将足爪砸向地面,反复多次,直到附着物脱落后才停止(~3.21 s,n=11)。若顿足行为无法使附着物脱落,便会出现俯身啄除行为。

Ⅲ-B-11.仰身振翅Rise-flap(图 5-46.)

双足站立,颈部极度向上,双翼同时向外张开并向上举,到达极限位置后用力向前扇动。约3.41 s(n=26)后,头颈下降复位,两翼收回。一般作为去除冰雪或清洁身体后残留的水分的动作出现,亦见于飞离夜栖地前的准备动作。

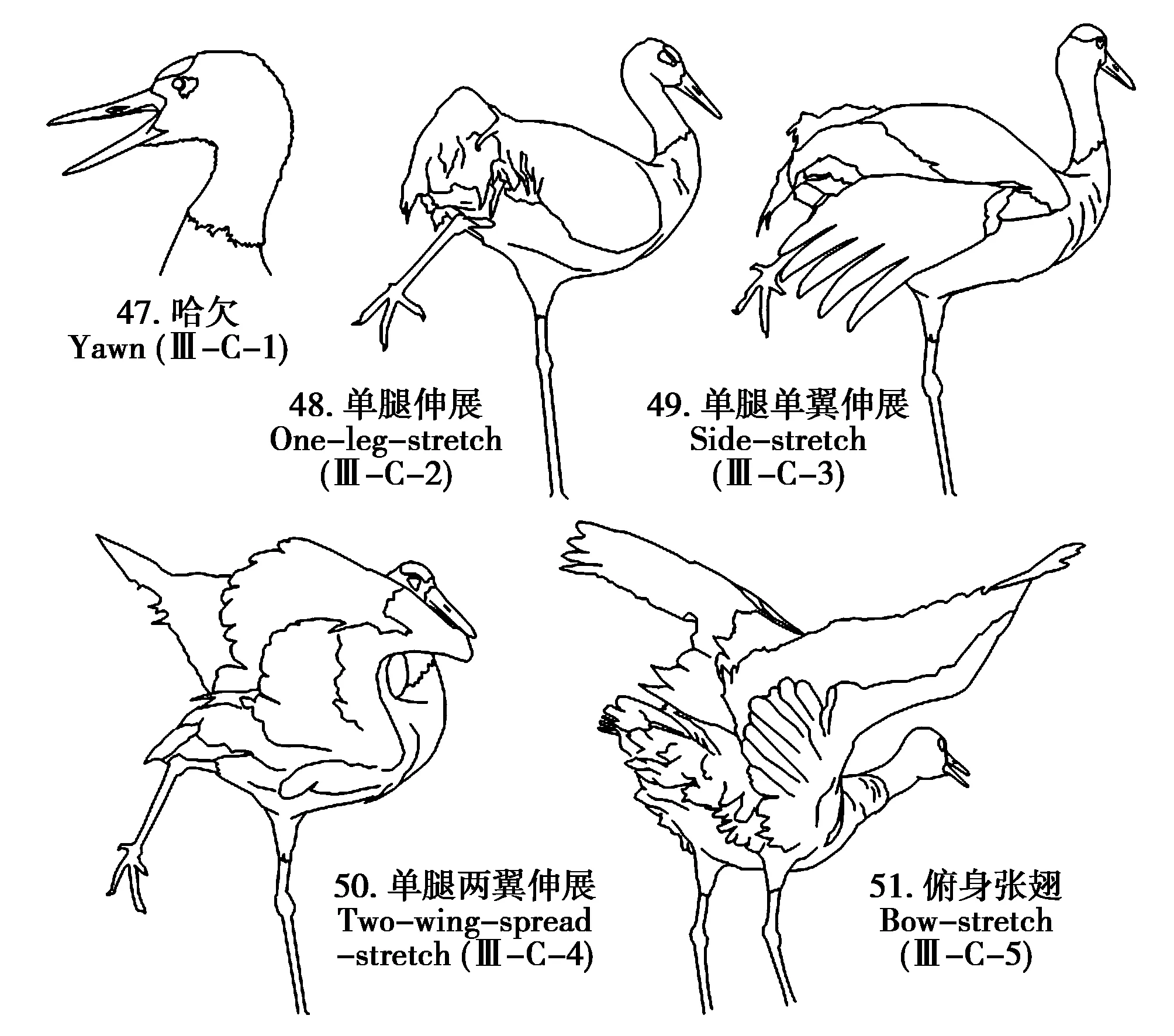

Ⅲ-C.伸展StretchⅢ-C-1.哈欠Yawn(图 6-47.)

躯干水平,颈部直伸,喙部张开至30°角左右,并在30°~35°角之间反复开合,头部同时左右轻摆。约5.52 s(n=18)后喙闭合,眨眼,动作完成。

Ⅲ-C-2.单腿伸展One-leg-stretch(图 6-48.)

躯干前倾,颈部略向后屈,一腿向后缓慢蹬出,至跗蹠部同胫跗部夹角约为135°时保持,进而继续缓慢后蹬至腿完全伸直;保持此姿势,躯干继续前倾(~15.60 s,n=25)。

Ⅲ-C-3.单腿单翼伸展Side-stretch(图 6-49.)

类似单腿伸展,但同侧翼向外同时伸出呈弓形。腿翼至最大幅度后保持,持续约10.66 s(n=21)。

Ⅲ-C-4.单腿两翼伸展Two-wing-spread-stretch(图 6-50.)

类似单腿伸展,但两侧翼向外同时伸出至最大幅度后保持(~9.87 s,n=20)。

Ⅲ-C-5.俯身张翅Bow-stretch(图 6-51.)

类似于俯身抖颈,但两翼动作不同且诡异——身体前倾,两翼上举至次级飞羽着生部竖直后,初级飞羽着生部向外完全打开,并在水平方向反复开合(~5.98 s,n=6)。

图6 保养行为(Ⅲ-C-1~5)Fig.6 Maintenance behavior(Ⅲ-C-1~5)

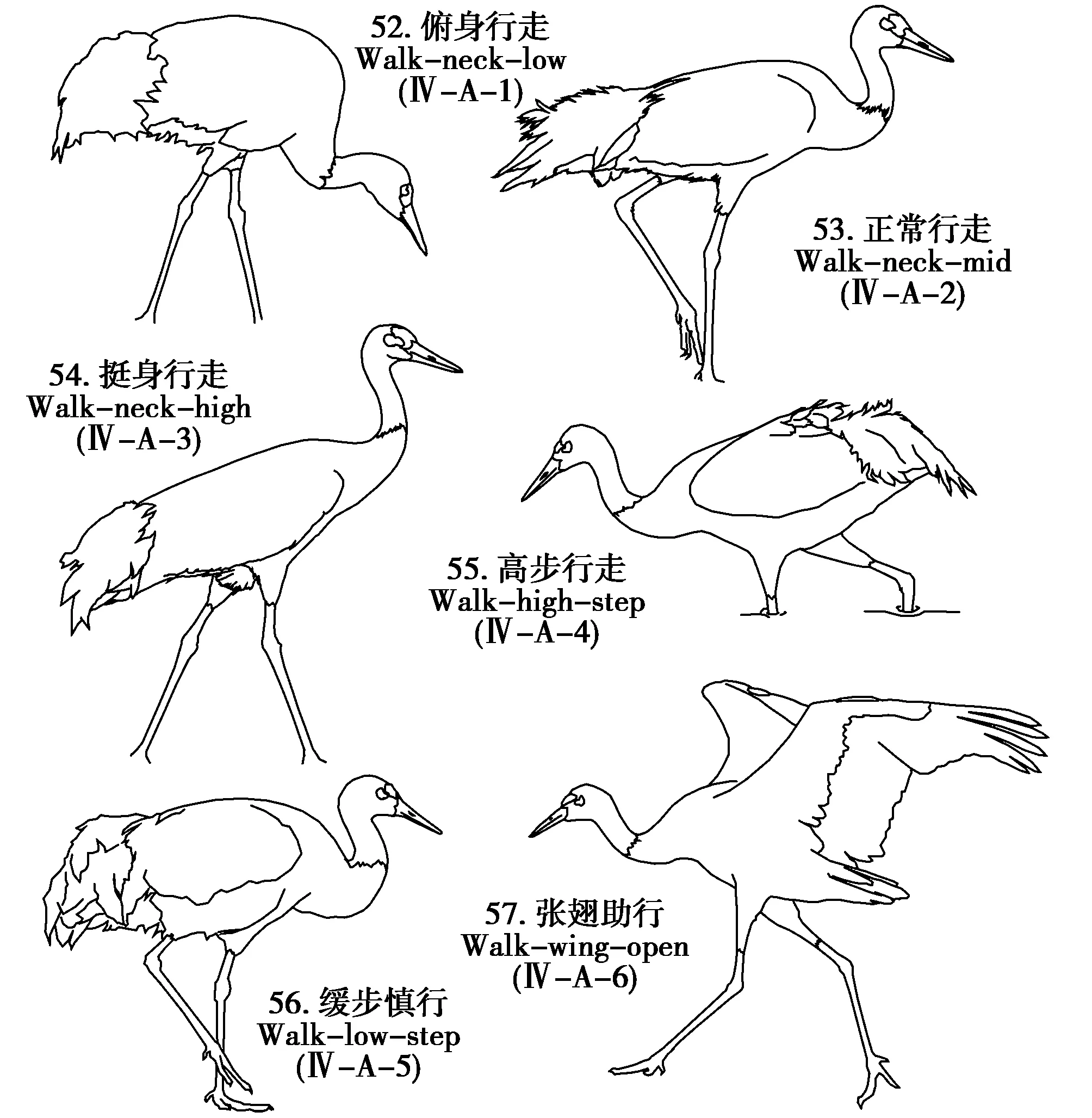

Ⅳ-运动行为LocomotoryⅣ-A.行走AmbulatoryⅣ-A-1.俯身行走Walk-neck-low(图 7-52.)

躯干前倾,颈部略屈曲向下而喙部指向地面。常见于觅食过程当中,个体常慢速走动而目光左右扫视食物(n>100)。

Ⅳ-A-2.正常行走Walk-neck-mid(图 7-53.)

躯干基本水平,颈部略弯曲,头部略向下指(n>100)。

Ⅳ-A-3.挺身行走Walk-neck-high(图 7-54.)

类似正常行走,但躯干略后倾,头颈极度向上,头部基本水平向前(n>100)。

Ⅳ-A-4.高步行走Walk-high-step(图 7-55.)

颈部弯曲而头部向前,躯干极度前倾以将腹部抬离水面。常见于在水中行走时(n>100)。

图7 运动行为(Ⅳ-A-1~6)Fig.7 Locomotory(Ⅳ-A-1~6)

Ⅳ-A-5.缓步慎行Walk-low-step(图 7-56.)

仅见于个体慢速通过冰面。类似于正常行走,但羽毛蓬起且两翼略抬高,步幅小,速度慢,且后足抬起后足趾几不收拢即向前迈出(n>100)。

Ⅳ-A-6.张翅助行Walk-wing-open(图 7-57.)

仅见于个体快速通过冰面。躯干后倾而头颈前伸,步伐极大,同时两翼上举并扇动以保持平衡(n>100)。

Ⅳ-B.奔跑Run

个体形态类似于俯身行走,正常行走或挺身行走,但步频显著高于行走(n>100)。

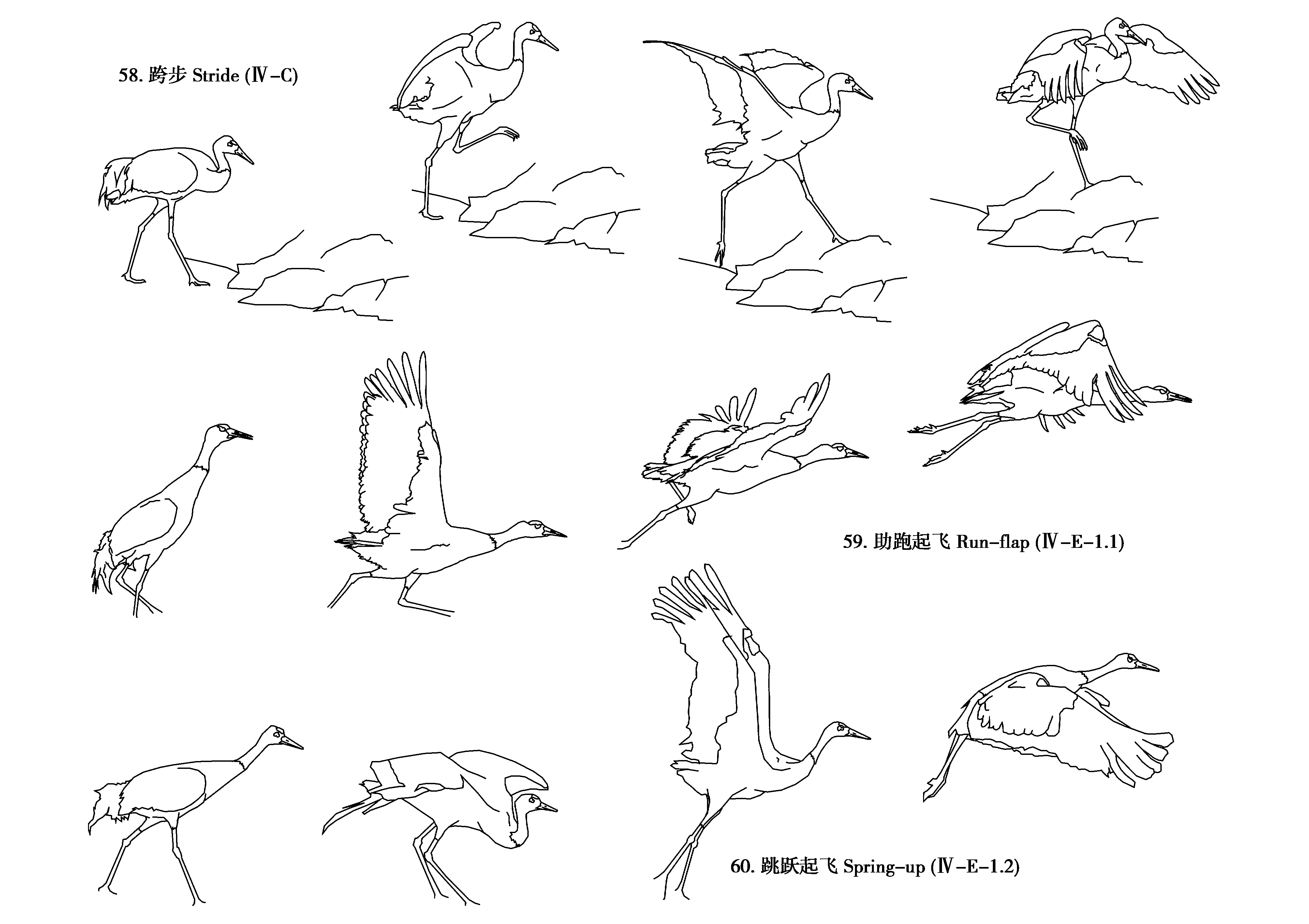

Ⅳ-C.跨步Stride(图 8-58.)

见于个体在跨过沟坎或越过障碍物时。头颈向上,两翼上举同时扇动,一足蹬地跨过障碍,另一足向腹部收回复向前探出(n>100)。

Ⅳ-D.跳跃Leap

双足站立,颈部屈曲,躯干明显前倾;双腿弯曲并向下蹬地,两翼同时打开(罕见扇动),随后垂直跳离地面(n>100)。

图8 运动行为(Ⅳ-C~E-1.2)Fig.8 Locomotory(Ⅳ-C~E-1.2)

Ⅳ-E.飞行FlightⅣ-E-1.起飞TakeoffⅣ-E-1.1.助跑起飞Run-flap(图 8-59.)

个体起飞采取的最常见方式。双足站立,躯干首先极度前倾,头颈向上直伸,颈部略向后弓出,保持该姿势(“预飞行姿势”,表达强烈的起飞信号[8]);随后颈部向前摆出,躯干水平,向前跨步;同时两翼向外水平伸出并快速扇动,约3.21 s(n=41)后双腿抬离地面。

Ⅳ-E-1.2.跳跃起飞Spring-up(图 8-60.)

类似跳跃,但两翼打开后猛烈扇动,随后转向,扇翅顺风向飞离(~0.71 s,n=41)。常见于助跑距离不足或迎强风站立时。

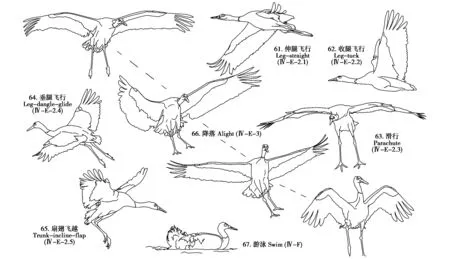

Ⅳ-E-2.飞行及滑翔Flap & GlideⅣ-E-2.1.伸腿飞行Leg-straight(图 9-61.)

头颈平伸,双腿向后直伸且足爪合拢,头颈、躯干及腿爪几呈直线(n>100)。

Ⅳ-E-2.2.收腿飞行Leg-tuck(图 9-62.)

类似伸腿飞行,但双腿折叠回收于腹下(n=16)[26]。

Ⅳ-E-2.3.滑行Parachute(图 9-63.)

躯干水平或略后倾,颈部略扬起,头部有时扬起有时环顾左右,两翼水平张开(少见扇动),双腿自然下垂(n=5)。

Ⅳ-E-2.4.垂腿飞行Leg-dangle-glide(图 9-64.)

类似滑行,但飞行时颈部直伸向前(n>100)。

Ⅳ-E-2.5.扇翅飞越Trunk-incline-flap(图 9-65.)

身体倾斜约同地面呈45°,颈部水平伸出,双腿自然屈曲下垂,两翼快速扇动(n>100)。见于短距离飞越河流或沟谷,亦作为洗澡后去除身体水分的动作出现。

Ⅳ-E-3.降落Alight(图 9-66.)

两翼向外水平伸出,双腿自然下垂,尾羽完全打开,颈及躯干由水平挺向竖起以减速,期间头部始终指向着陆点;接触地面瞬间,腿部斜向下蹬出,足趾张开,双足同时着陆,随后向前迈出,期间两翼完全张开辅助减速(n>100)。若短距离飞行或着陆点空间狭促,着陆时两翼不停扇动以快速减速。

图9 运动行为(Ⅳ-E-2.1~F)Fig.9 Locomotory(Ⅳ-E-2.1~F)

Ⅳ-F.游泳Swim(图 9-67.)

仅在繁殖地有过一次记录(n=1)。两翼向上抬起(仍保持收回状),尾羽同时耸起,个体浮于水中双腿轮流滑水,姿势笨拙,速度缓慢。

Ⅴ-摄食、排遗和排泄Ingestion,EgestionandExcretion

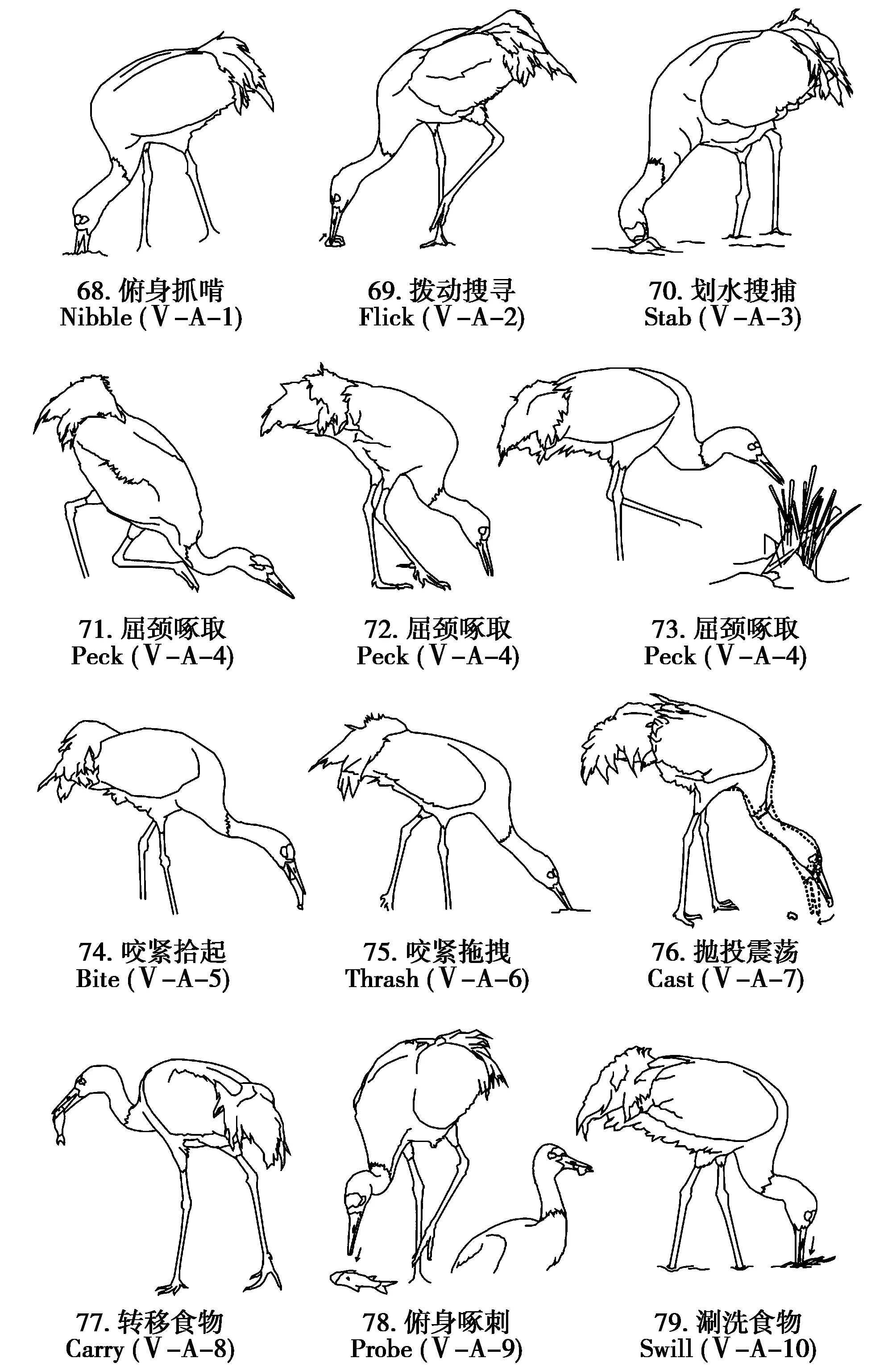

Ⅴ-A.觅食ForagingⅤ-A-1.俯身抓啃Nibble(图 10-68.)

双足站立,躯干前倾,颈部弯曲,喙部几乎垂直插入地表约1/4喙长的深度。上下喙快速小幅开合,用以啮咬土块。常见于个体翻掘埋于地下的土豆等食物时(n>100)。

Ⅴ-A-2.拨动搜寻Flick(图 10-69.)

双足站立,颈部弯曲,喙部插入土壤或贴靠被移动的物体;头部横向扭动,使用喙端来移动物体。常见于个体拨开土壤或牦牛的干粪等物体以寻找隐藏昆虫时(n>100)。

Ⅴ-A-3.划水搜捕Stab(图 10-70.)

双足站立,躯干前倾,颈部近乎直伸,喙部张开完全没入水中,但双眼一般暴露在水面外;躯干扭转,头部以同水面约呈45°的角度在水中大幅划动。常见于个体搜捕水中的鱼时(n>100)。

Ⅴ-A-4.屈颈琢取Peck(图 10-71~73.)

双足站立,颈部首先收缩,随后喙部轻开并迅速向外刺向食物。除常见于黑颈鹤啄食地表食物外,亦见其啄食灌木上的冰凌,捕捉网围栏上的蜘蛛,草甸上的鼠兔及蜥蜴等,身体姿态随食物位置不同而有差异(n>100)。

Ⅴ-A-5.咬紧拾起Bite(图 10-74.)

姿态近似张嘴抓啃,但喙部开合角度更大,咬合更有力,随后颈部抬升,躯干随之水平。常见于个体从地面拾起土豆或从水中叼起鱼等较大体积食物时(n>100)。

Ⅴ-A-6.咬紧拖拽Thrash(图 10-75.)

双足站立,躯干前倾,喙部紧咬食物而颈部收屈,随后身体以足为轴心猛烈向上(后)拖拽食物,直至其离开地面。常见于个体拔拽植物的地下部分时(n>100)。

Ⅴ-A-7.抛投震荡Cast(图 10-76.)

双足站立,躯干前倾,喙部紧咬食物,头部摆动将其抛出。常见于个体将捕捉到的鱼甩扔上岸,或震荡黏附在土豆等植物地下部分食物上的泥土时(n>100)。

Ⅴ-A-8.转移食物Carry(图 10-77.)

喙部紧咬食物,采用俯身行走或正常行走将食物转移(n>100)。

图10 摄食、排遗和排泄(Ⅴ-A)Fig.10 Ingestion,egestion and excretion(Ⅴ-A)

Ⅴ-A-9.俯身啄刺Probe(图 10-78.)

双足站立,躯干前倾而颈部屈曲,喙部合拢并反复迅速刺向食物(19 s内记录到31次)。若食物卡在喙部,则常通过甩动头部将其去除。常见于个体杀死捕捉到的鱼时,但在野外过程中亦记录一个体喙部卡有大块土豆,据此推测其或通过此方式来穿刺以分裂大块食物。

Ⅴ-A-10.涮洗食物Swill(图 10-79.)

姿态近似抛投震荡,但喙部紧咬食物并反复按入水中,同时头部左右摆动以涮洗食物。常见于个体在水中清洗由泥水中获得的草本植物时(n=3)。

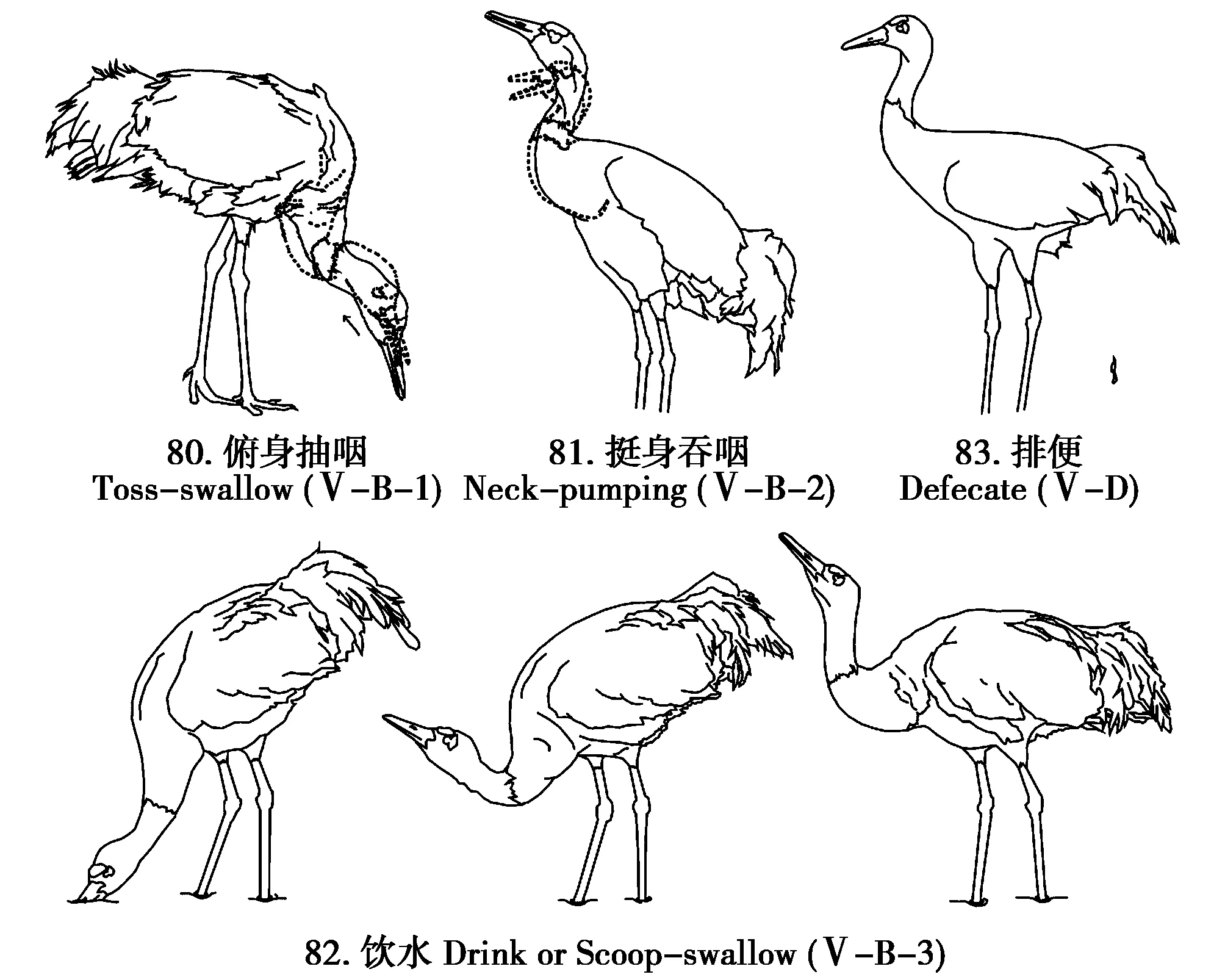

Ⅴ-B.吞咽SwallowingⅤ-B-1.俯身抽咽Toss-swallow(图 11-80.)

最常见的吞咽食物的方式,常见于个体吞咽进食小块食物时。颈部首先伸出,喙部咬紧食物,随后颈部快速收屈而后急停,喙部同时轻开,食物就惯性落入口中(n>100)。

Ⅴ-B-2.挺身吞咽Neck-pumping(图 11-81.)

常见于个体吞咽大块食物时,如鱼等。双足站立,躯干略后倾而颈部收屈,喙微张而后迅速向斜上伸出,直伸后咬紧食物收屈,反复多次,直到完成吞咽。吞咽完成后往往见上下喙快速小幅开合以为调整——似咂嘴——有时亦伴有眨眼(n>100)。

Ⅴ-B-3.饮水Drink or Scoop-swallow(图 11-82.)

双足站立,双腿微屈,躯干首先极度前倾,喙部微张插入水中,身体继续前倾,颈部向后弯曲,以使得水流入喙中;随后躯干上摆,头部扬起抬离水面,至躯干水平后头部上扬使水流入腹中,期间喙部保持微张直至饮水完成后才见闭合(~4.05 s,n=57)。

Ⅴ-C.呕吐Vomit

仅见于一次远距离野外观察,极类似于Masatomi(2004)对于白头鹤(Grusmonacha)呕吐行为的描述,分作摆喙(Bill-shake),张口(Gape)以及呕吐(Vomit)3个动作[4](n=1)。

图11 摄食、排遗和排泄(Ⅴ-B~D)Fig.11 Ingestion,egestion and excretion(Ⅴ-B~D)

Ⅴ-D.排便Defecate(图 11-83.)

双腿站立,颈部略弯曲,躯干略前倾同时两翼及尾轻抬高,排便。动作完成后躯干恢复水平,两翼及尾降下,常伴随以提翅及摆动尾部。亦见于飞行过程中,彼时个体往往滑行或采伸腿飞行姿势(n>100)。

3 讨论

以往对于鹤类个体行为的研究已经为当前对于鹤类个体行为的讨论奠定了牢固的基础[3-4],但时至今日仍有许多问题难以厘清。由于鹤类个体行为的连续性及其灵活性,个体行为的固定分类框架在面对具有多种功能的行为时常难以适用,进而导致了在分类体系中行为重复及混淆的出现。因此,基于野外观察中获得的材料,我们在此对黑颈鹤个体行为分类体系中的一些问题展开讨论。

依据行为的动机,Ellis et al.(1991)将鹤类的个体行为分为如下8个类别:1)孵化行为(Hatching),2)姿势(Posture),3)休憩行为(Sleep-related behavior),4)感知行为(Sensory-related behavior),5)保养行为(Maintenance behavior),6)体温调节及呼吸(Thermoregulatory and respiratory),7)运动行为(Locomotory)以及8)摄食、排遗和排泄(Ingestion,egestion and excretion)(以下简称“Ellis系统”)[3]。随后,从行为形态的角度出发,其进一步将每一大类细分作不同的级别和条目[3]。而在此分类体系中,“鸣叫”(Vocalizations)以及“其他涉及种内及种间关系的行为”被排除在外[3]。而正是基于这样的考虑,本文将“孵化行为”亦从该分类体系中去除。原因在于,作为黑颈鹤繁殖期最为关键的阶段,孵化并非一个独立发生的动作,反而,其是基于亲鸟与其后代间存在的种内相互关系而出现的。基于此,我们倾向于认为孵化行为从属于繁殖行为,进而应归类至繁殖行为(社会行为)的范畴当中。其次,个体的姿势在绝大部分情况下均是作为其他个体或社会行为的组成或表现而存在,而该行为本身并不具有如“站立”或“卧下”的动机,因此不应与后续按照行为动机分类的行为并列。诚然,对于姿势的描述可以极大地便利对于其他个体行为的讨论,因此在本文中,仅移除了“姿势”一类前可能导致困惑和混淆的编号,并将其更名为更准确的“静息姿态”。

休憩行为(Ⅰ)同之前的认知相比具有更高的多样性。以眼睛长时间闭合作为标准,我们增补了一类新的行为,即倚背休憩(Ⅰ-C)。反而,本文将“藏头观察”(Head-tuck-watch)从该分类中移除,原因在于这一观察环境的动作多出现于个体休息前后,因而应属于感知行为的范畴。

基于对行为发生动机的考量,本文将感知行为(Ⅱ)重新划分为观察(Ⅱ-A)和警戒(Ⅱ-B)两类,而外界刺激是区别以上两类行为的唯一标准。换言之,外界刺激的存在与否直接决定了个体对于外界的感知是被动亦或主动。本文认为,个体对于外界环境或其他物体的主动感知即是观察,而作为对于外界刺激的响应而出现的对刺激的感知则为警戒。此外,观察几乎存在于黑颈鹤所有个体以及社会行为当中——只要双眼睁开,个体即处于观察这一状态当中。Ellis系统将个体的警戒行为分为3类,即低态双目凝视(Ⅱ-B-1),中态双目凝视(Ⅱ-B-2)以及高态双目凝视(Ⅱ-B-3)[3],本文极为赞同。而且,无论个体采站姿、卧姿或何种姿态,以上3种行为均可以极为准确地表征个体的警戒程度,且同样适用于其他鹤类(如白头鹤等)。同时,不可否认的是,警戒行为常具有更多的社会性内涵,但考虑个体行为分类体系的完整性,在此仍将其作为个体行为谱的一部分呈现。此外,本文认为Ellis系统中的“眨眼”(Blink)或“单眼凝视”(Monocular-gaze)作为感知的动作方式而非具体的行为或姿态,应当从该行为分类体系中移除。

保养行为(Ⅲ)是鹤类个体行为中最为复杂的部分,原因即在于单个动作或行为常具有极其丰富的功能和含义。相较于Ellis系统[3],首先,本文移除了“舒适行为”(Comfort Behavior)这一类别,并将其下行为按照动作发生的形态进行了细分和重组。原因在于,舒适行为这一类目过多地强调了行为发生的动机是“舒适身体而非清洁”,然而对于某些行为来说以上动机在实际情况当中往往是极其微妙,难以区分的。例如,抖动行为(Ⅲ-B)可以起到舒适身体和蓬松羽毛的作用,但其同时亦具备将体表附着的污物移除的功能。基于此,我们将保养行为分为3大类别,即体表保养(Ⅲ-A),抖动(Ⅲ-B)以及伸展(Ⅲ-C),并移除了原分类框架当中“其他舒适行为”(Other Comfort Behavior)这一含糊的说辞。在体表保养(Ⅲ-A)当中,我们去除了“蓬松和顺滑”(Fluff and sleek)这一行为,因为其实际上是抖动身体所带来的必然结果。考虑到解除瘙痒这一相同动机,我们将摩擦头部(Ⅲ-A-3)同抓挠(Ⅲ-A-4)置于一处。此外,在这一分类中本文进行了诸多增补——如俯身啄除(Ⅲ-A-6)和加温融化(Ⅲ-A-7)见于个体去除附着在其胫跗部的冰块,滑行蹭足(Ⅲ-A-8)见于个体由黏土地飞离后(亦见于灰鹤Grusgrus),润湿头部(Ⅲ-A-10)仅在繁殖地有过1次记录,而本文猜测其可能是个体抵御蚊虫、解除瘙痒的一种方式。在抖动(Ⅲ-B)当中,由于动作的相似性,我们将甩喙(Ⅲ-B-1)、甩足(Ⅲ-B-9)以及仰身振翅(Ⅲ-B-11)均移至此处。在野外观察中发现,黑颈鹤对于附着在其喙部及胫跗部的污物极其介意,往往停下其正在进行的觅食并不惜花费大量时间对其处理。顿足(Ⅲ-B-10)在本文中首次得到记录,其常见于黑颈鹤于黏土地中觅食时(n=11),推测其可能由甩足行为衍生而来。此外,提翅(Ⅲ-B-7,n=57)以及摆尾(Ⅲ-B-8,n=69)通常作为理羽、抖动或伸展之后的整理动作出现,因此在整理行为中具有较高的出现频率。在伸展(Ⅲ-C)中,除去哈欠(Ⅲ-C-1)与俯身张翼(Ⅲ-C-5),其他3种行为出现频率相近(n=25/21/20),原因在于其常作为一完整的行为序列依次出现。与之类似,蜷翅击水(Ⅲ-A-9.3),倾体扬水(Ⅲ-A-9.4)以及头颈扬水(Ⅲ-A-9.5)亦常作为清洗身体的行为序列而记录到相近的出现频次(n=13/8/11)。

我们移除了Ellis系统中“体温调节以及呼吸”这一行为类别[3],原因在于其中行为常作为其他行为的组成部分(如“蓬松和顺滑体羽”),或明显作为其他行为表达的结果而出现(如“头顶裸皮的收缩与舒张”)。

在运动行为(Ⅳ)当中,基于对运动过程中身体姿态的考虑,我们对行走(Ⅳ-A)进行了重新分类。其中,缓步慎行(Ⅳ-A-5)和张翅助行(Ⅳ-A-6)作为黑颈鹤以不同速度通过冰面的两类行为被新记录到,而跨步(Ⅳ-C)作为黑颈鹤翻越障碍物的一种行为被新添入其个体行为谱中。Ellis系统中存在“行为过渡动作”(“Transitional action patterns”)这一概念[3],但本文认为其列举的该范畴内的许多动作均属于某些特定行为而鲜见独立表达,因而在此并不采纳该类目,并将其下动作归回其从属的行为序列。依据飞行的时间顺序,我们将飞行过程中的行为进行了重新组合与分类,即起飞(Ⅳ-E-1),飞行及滑翔(Ⅳ-E-2)以及降落(Ⅳ-E-3)。此外,在野外观察中发现,收腿飞行(Ⅳ-E-2.2)常见于越冬地及迁徙停歇地的寒冷清晨,因而在此附议Kong et al.(2016)认为该行为为黑颈鹤在飞行时温暖腿部的方式的观点[26]。此外,在先前的野外工作当中亦在类似环境条件下于黑颈鹤同属其他物种中有过记录,如白头鹤、丹顶鹤以及灰鹤等。

在摄食、排遗和排泄(Ⅴ)当中,本文基于“搜寻食物——获得食物——处理食物”的逻辑顺序对觅食行为进行了重新整理。先前Ellis et al.(1991)在其行为谱中列有“喙部拨动”(Bill-flick),“喙部推开”(Bill-push-open)以及“喙部侧推”(Bill-side-push)3种行为[3],然而在野外观察中注意到以上3种常作为黑颈鹤处理地下埋藏食物的3种动作而混杂出现,难以区分。因此,本文赞同Masatomi(2004)的观点[4],将其合为拨动搜寻(Ⅴ-A-2)一类。“摆喙”(Bill-shake),“张口”(Gape)以及“呕吐”(Vomit)在野外仅见于黑颈鹤试图将食物吐出,因此我们将其同归为呕吐(Ⅴ-C)一类。此外,同预飞行姿势相类似,排便(Ⅴ-D)亦常作为某些情况下个体准备逃离的动机而表达。

本文新近增补的许多新的行为均记录于特殊的环境条件下:挑出(Ⅲ-A-1.2)、俯身啄除(Ⅲ-A-6)以及加温融化(Ⅲ-A-7)均记录于降大雪后,滑行蹭足(Ⅲ-A-8)与顿足(Ⅲ-B-10)均记录于个体于黏土地觅食后,而缓步慎行(Ⅳ-A-5)以及张翅助行(Ⅳ-A-6)均记录于个体在通过结冰水面时。以上行为在没有相应特殊条件时均未有记录。

作为基于野外观察数据的黑颈鹤个体行为研究的阶段性总结,本文在对材料处理时仍难以逃离许多难以决断的问题,诸如:个体行为通常作为连贯的序列出现,而固定的分类体系及框架常常难以对一些动作或功能较为模糊的行为做出明确的区分;同时,个体本身在面对不同的环境条件时会主动地对行为发生的动作、持续时间以及先后次序等属性进行调整,甚至在一常见的固定行为序列中添加新的动作以满足实际需求。因此,究竟应以何种标准用于个体行为的分类?如何对分类体系和框架进行调整才可能无重复无遗漏地对行为进行整理?以上困惑或贯穿于整个鹤类行为研究的始终,但可以确定的是随着基础的行为学工作的不断积累与讨论,这些问题必将逐渐明朗清晰。

致谢:感谢何芬奇老师与刘小龙老师在行为描述上给出的建议。感谢李苞、温立嘉在外业数据收集上给予的帮助,感谢于凤琴女士、杨杰才让、花青加、智华喇嘛、扎西桑俄堪布以及董江天女士在野外工作中给予的帮助。

[1] Rusak B,Zucker I.Biological rhythms and animal behavior[J].Annual Review of Psychology,1975,26(1):137-171.

[2] Werner E E.Individual behavior and higher-order species interactions[J].The American Naturalist,1992,140:S5-S32.

[3] Ellis D H,Archibald G W,Swengel S,et al.Compendium of crane behavior.Part1:individual(nonsocial)behavior[C]//Harris J T.Proceedings of the 1987 International Crane Workshop.Baraboo:International Crane Foundation,1991:225-234.

[4] Masatomi H.Individual(non-social)behavioral acts of hooded cranesGrusmonachawintering in Izumi,Japan[J].Journal of Ethology,2004,22(1):69-83.

[5] Olsen S L.The fossil record of birds[C]// Farner D S,King J R,Parkes K C.Avian Biology Ⅷ.New York:Academic Press,1985:80-238.

[6] Voss K S.Behavior of the greater sandhill crane[D].University of Wisconsin M.S.Thesis,Madison:University of Wisconsin,Madison,1976.

[7] Nesbitt S A,Archibald G W.The agonistic repertoire of sandhill cranes[J].The Wilson Bulletin,1981,93(1):99-103.

[8] Johnsgard P A.Cranes of the World:4.ecology and population dynamics[C]//Johnsgard P A.Cranes of the World.Bloomington:Indiana University Press,1983:35-43.

[9] Masatomi H,Kitagawa T.Bionomics and sociology of Tancho or the Japanese crane,Grusjaponensis,Ⅱ.ethogram[J].Journal of the Faculty of Science Hokkaido University Series Ⅵ.Zoology,1975,19(4):834-878.

[10] 钱燕文.鹤类的研究[J].动物学杂志,1992,27(2):41-47.[Qian Yanwen.Studies on cranes[J].Chinese Journal of Zoology,1992,27(2):41-47.]

[11] Bai Xiujuan,Ma Jianzhang.Speciation of the black-necked crane[J].Journal of Northeast Agricultural University,2002,9(2):32-37.

[12] Archibald G W,Meine C D.Family gruidae(cranes)[C]//Hoyo J,Elliott A,Sargatal J.Handbook of the birds of the world,Vol.3,Hoatzin to Auks.Barcelona:Lynx Edicions,1996:60-89.

[13] 李德浩,周志军.隆宝滩黑颈鹤育幼期种群的行为[J].野生动物,1985,6(6):4-9.[Li Dehao,Zhou Zhijun.Observations on breeding behavior of the black-necked crane(Grusnigricollis)at Longbaotan in Qinghai Province[J].Chinese Wildlife,1985,6(6):4-9.]

[14] 李德浩,周志军,吴志康,等.四川松潘草地黑颈鹤的繁殖种群结构和育雏期行为观察[M]//黑龙江省林业厅.国际鹤类保护与研究.北京:中国林业出版社,1990:39-41.[Li Dehao,Zhou Zhijun,Wu Zhikang,et al.Structure and behavior of the breeding population of black-necked cranes in Songpan Meadow in Sichuan Province[M]//Heilongjiang Forestry Bureau.International crane conservation and research.Beijing:China Forestry Press,1990:39-41.]

[15] 杨炯蠡,黄鹤先,管毓和.草海黑颈鹤和灰鹤越冬期生态行为学的比较研究[J].环保科技,1992(Z1):44-49.[Yang Jiongli,Huang Hexian,Guan Yuhe.Comparison of the wintering behavior of the black-necked crane(Grusnigricollis)and Common Crane(Grusgrus)in Caohai,Guizhou[J].Environmental Protection and Technology,1992(Z1):44-49.]

[16] 李凤山,马建章.越冬期黑颈鹤个体行为生态的研究[J].生态学报,2000,20(2):293-298.[Li Fenshan,Ma Jianzhang.Behavioral ecology of black-necked crane during winter at Caohai,Guizhou,China[J].Acta Ecologica Sinica,2000,20(2):293-298.]

[17] Masatomi H.Analysis on unison calls of black-necked cranes kept in captivity[J].Bulletin of Akan International Crane Center,2002,2:21-25.

[18] 邝粉良,刘宁,仓决卓玛,等.藏北黑颈鹤繁殖前期的昼间活动时间分配[J].浙江农林学院学报,2007,24(6):686-691.[Kuang Fenliang,Liu Ning,Cangjue Zhuoma,et.al.Diurnal time-activity budgets ofGrusnigricollisfor the pre-laying phase in northern Tibet[J].Journal of Zhejiang Forestry College,2007,24(6):686-691.]

[19] 赵建林,韩联宪,冯理,等.云南纳帕海黑颈鹤越冬行为与生境利用初步观察[J].四川动物,2008,27(1):87-91.[Zhao Jianlin,Han Lianxian,Feng Li,et al.Wintering behaviors and habitat using of black-necked crane in Napahai Nature Reserve,Yunnan Province[J].Sichuan Journal of Zoology,2008,27(1):87-91.]

[20] 王凯,杨晓君,赵健林,等.云南纳帕海越冬黑颈鹤日间行为模式与年龄和集群的关系[J].动物学研究,2009,30(1):74-82.[Wang Kai,Yang Xiaojun,Zhao Jianlin,et al.Relations of daily activity patterns to age and flock of wintering black-necked crane(Grusnigricollis)at Napa Lake,Shangri-La in Yunnan[J].Zoological Research,2009,30(1):74-82.]

[21] 孔德军,杨晓君,钟兴耀,等.云南大山包黑颈鹤日间越冬时间分配和活动节律[J].动物学研究,2008,29(2):195-202.[Kong Dejun,Yang Xiaojun,Zhong Xingyao,et al.Diurnal time budget and behavior rhythm of wintering black-necked crane(Grusnigricollis)at Dashanbao in Yunnan[J].Zoological Research,2008,29(2):195-202.]

[22] 次仁顿珠,普布,扎西次仁.西藏澎波河谷越冬黑颈鹤的行为观察[J].西藏科技,2012(7):67-68,76.[Ciren D,Pu B,Zhaxi R.Behavior observation of the black-necked craneGrusnigricollisin Pengbo Valley[J],Tibet’s Science and Technology.2012(7):67-68,76.]

[23] 向丹凤,王金亮,钟兴耀,等.大山包黑颈鹤对旅游干扰的行为反应研究[J].环境科学导刊,2014,33(1):1-5.[Xiang Danfeng,Wang Jinliang,Zhong Xingyao,et al.Dashanbao onGrusnigricollisbehavioral responses to tourism disturbance[J].Environmental Science Survey,2014,33(1):1-5.]

[24] 卯霞,丁伟,李国刚,等.云南巧家马树黑颈鹤日间越冬时间分配和活动节律[J].野生动物学报,2014,35(3):307-310.[Mao Xia,Ding Wei,Li Guogang,et al.Diurnal activity budget and behavior of wintering black-necked crane(Grusnigricollis)at Mashu in Yunan[J].Chinese Journal of Wildlife,2014,35(3):307-310.]

[25] 邝粉良,仓决卓玛,李建川,等.藏北黑颈鹤孵卵期的昼间时间分配和行为节律[J].楚雄师范学院学报,2015,30(6):22-25,41.[Kuang Fenliang,Cangjue Zhuoma,Li Jianchuan,et al.Diurnal time budget and behavior rhythm ofGrusnigricollisduring incubating phase in northern tibeten[J].Journal of Chuxiong Normal University,2015,30(6):22-25,41.]

[26] Kong Dejun,Li Fengshan,Liu Qiang,et al.Flight of black-necked cranes(Grusnigricollis)with legs drawn up:behavioral responses to low temperature and duration of exposure[J].The Wilson Journal of Ornithology,2016,128(1):144-149.

[27] Lu Guangyi,Wang Rongxing,Ma Lirong,et al.Characteristics of dry upland roosts of the black-necked crane(Grusnigricollis)wintering in Yongshan,China[J].The Wilson Journal of Ornithology,2017,129(2):323-330.

[28] 车烨,杨乐,李忠秋.西藏拉萨越冬黑颈鹤家庭群的警戒同步性[J].生态学报,2018,38(4):1-7.[Che Ye,Yang Le,Li Zhongqiu.Vigilance synchronization of wintering black-necked crane(Grusnigricollis)families in Tibet[J].Acta Ecologica Sinica,2018,38(4):1-7.]

[29] 李筑眉,李凤山.黑颈鹤研究[M].上海:上海科技教育出版社,2005.[Li Zhumei,Li Fengshan.Research on the black-necked crane[M].Shanghai:Shanghai Scientific and Technological Education Publishing House,2005.]

As one of the inherent characteristics of birds,various behaviors are displayed to fulfil their needs of survival[1].Based on various motivations,bird behaviors can be recognized and classified as individual(non-social)or social behavior,and between which the individual behaviors are the most crucial components and the elementary units of all avian behaviors[2].However,under some circumstances,the social meaning expressed by recognized individual behaviors may obscure the division between social and individual behaviors[3],resulting in serious difficulties for both academic and practical work.Therefore,it is necessary to establish an elaborate ethogram of individual behaviors as a fundamental tool for further study of complete behavior sequences,social behaviors and abstruse behavioral mechanisms[4].

Gruiformes is an ancient group of avian species[5],many meaningful efforts have been made in their ethological study[6-10].As an endemic species on the Tibetan Plateau,the Black-necked CraneGrusnigricollisrepresents a unique evolutionary branch that adapts to the alpine environment[11-12].In the ethological study on the Black-necked Crane,reported work basically focused on the fundamental behavior and associated time budget[13-28];while its individual behaviors,especially its classification and categorization,have not been well explored,and limited attempts were made merely based on captive individuals[3,17].The lack of the unification in recognition and classification of the non-social behaviors of the Black-necked Crane greatly weakens the credibility of its further ethological study,which are commonly based on various vague and coarse categories,leading to great difficulties in the comprehension and comparison of these researches.

Consequently,based on the field observation and associated video materials,we made elaborate descriptions and illustration for the individual behavior of the Black-necked Crane.We aim that this work could provide a complete individual behavior compendium for the Black-necked Crane,in order to pave a safe way for further ethological study on this unique crane lineage.

1 Methods

1.1 Fieldwork and Data Collection

Breeding observation occurred in April-June 2013 and April-July 2014 in Gansu,Qinghai,and Sichuan Province and the Tibet Autonomous Region,China,basically covering all the known populations of the Black-necked Crane.During fieldwork,besides direct observation in the wild,video cameras were used to record the Black-necked Crane’s ethon.Finally,we obtained ~63 200 effective images and approximately 8 930-minute-long of effective video records in total.Based on these materials,we categorized,described,and illustrated the individual(non-social)behaviors(ethons)of the Black-necked Crane,and then finished the ethogram in Adobe Illustrator CC.

1.2 Framework and Terminology

We generally followed the compendium put forward by Ellis et al.(1991)and supplemented by Masatomi(2004)as the framework for categorizing the crane’s ethons,which proposed a detailed framework of individual(non-social)behaviors for crane family[3-4];the description of the behaviors was according to the work of Masatomi and Kitagawa(1975)on the Red-crowned CraneGrusjaponensis,which presented a set of complete and accurate principles for describing crane individual behaviors[9].New supplemental ethons were named following the nomenclature of Ellis et al.(1991)and underlined[3].For a more intuitive understanding of Black-necked Cranes’ behavior,frequency and duration of uncommon quantifiable ethons(n<100)were counted[4].To avoid possible confusions,here we only involve those ethons that have been recorded in our own field work,or has been reported by previous studies on this species[3-4].

2 Results

Based on the elementary Still Postures,the Black-necked Crane’s individual behavior could be categorized as:Ⅰ.Sleep-related Behavior,Ⅱ.Sensory-related Behavior,Ⅲ.Maintenance Behavior,Ⅳ.Locomotory,Ⅴ.Ingestion,Egestion and Excretion.

Still PosturesSP-A.Stand(Fig.1-1.)

The crane stands on both feet.Legs are usually kept parallel,but may be in tandem in a transitory stand during movements.

SP-B.One-leg-stand(Fig.1-2.)

The crane’s body is supported by one leg,while the other is tucked or dangled.

SP-C.Lie(Fig.1-3.)

Both legs are folded beneath the trunk.On a warm afternoon in the wintering grounds,Black-necked Cranes were commonly observed resting in this posture,but only a single record was made in the breeding grounds(not hatching).

Ⅰ.Sleep-related BehaviorⅠ-A.Head-forward-sleep(Fig.1-2.)

With the trunk held horizontally and the neck retracted fairly,the crane rests with its head kept low(n>100).

Ⅰ-B.Head-droop-sleep(Fig.1-1.)

Similar to Head-forward-sleep,but the head is kept lowest,with bill pointing steeply down to the ground(n>100).

Ⅰ-C.Head-lean-sleep(Fig.1-4.)

The trunk held horizontally and both wings folded faintly up,the crane bends its neck backward and leans its head on the back(n>100).

Ⅰ-D.Head-tuck-sleep(Fig.1-3.)

Similar to Head-lean-sleep,but the bill is kept obliquely down and is tucked into the dorsal feathers(n>100).

Ⅱ.Sensory-related BehaviorⅡ-A.Observe

This ethon were observed to occur with or as a part of other behaviors,such as seeking food or watching forward during movement,etc.During observing,the crane is usually relaxed with feathers sleeked and crown contracted(n>100).

Ⅱ-B.Vigilance

During vigilance,the crane behaves nervously to disturbances,with feathers fluffed and crown expanded.The degree of the vigilance could be accurately identified by the form of neck.

Ⅱ-B-1.Binocular-gaze-low(Fig.1-5.)

With trunk kept horizontally or slightly down,the crane gazes with its neck retracted fairly(n>100).

Ⅱ-B-2.Binocular-gaze-mid(Fig.1-6.)

Lifting the trunk slightly up,the crane gazes with its neck retracted slightly(n>100).

Ⅱ-B-3.Binocular-gaze-high(Fig.1-7.)

With the trunk held obliquely down,the crane gazes with its neck extremely stretched and the crown expanded(n>100).

Ⅲ.Maintenance BehaviorⅢ-A.Care of body surfaceⅢ-A-1.Preen

Preen is a comprehensive matrix of a series of ethons for removing foreign matter and parasites from the body surface,separating tangled feathers,promoting molting,etc.It occurs in all postures of the crane and could transform to cater different needs for various body parts.Part of typical ethons of preening were shown in Fig.2-12 to Fig.2-21.According to the subtle differences in the movements,preening could be categorized as:

Ⅲ-A-1.1.Nibble(Fig.2-8.)

Inserting the bill deeply into the feathers,the crane slightly opens and closes the bill,rapidly nibbling the base parts of feathers and body surface(n>100).

Ⅲ-A-1.2.Winkle(Fig.2-9.)

Frequently occurred after snowy nights,the crane inserts the bill deeply into its trunk feathers(dorsal coverts especially),then winkles out rapidly to tease apart tangled feathers(n>100).

Ⅲ-A-1.3.Comb-out(Fig.2-10.)

Tenderly biting the base of the primaries or rectrices,the crane slides its bill from the base to tip slowly,eliminating the water or hanging ice from long feathers-for the latter situation,the opening amplitude of the bill is exactly smaller than the size of the ice,but loose for the feather(n>100).

Ⅲ-A-1.4.Stroke(Fig.2-11.)

With the neck bent backward to one side,the crane presses its crown on the back,and then strikes the head with the bill swung,in order to sleek the windblown feathers on the back(n>100).

Ⅲ-A-2.Oil(Fig.2-22.)

Bending the head backward and slightly drooping one wing,the crane directs the bill to the uropygial gland,with the rectrices turned to the same side.The bill pushes aside the feathers above the gland,and then the crane daubs the oil on the bill and head through sliding movements.Via various preening movements,the crane smears this oil on the body(n=19).

Ⅲ-A-3.Head-rub(Fig.2-23.)

Similar to Stroke,but the head only rubs the mental parts and the scapular feathers,to relieve the itching of bare cap(~4.98 s,n=6).

Ⅲ-A-4.Scratch(Fig.3-24.)

This ethon could be divided into Head-scratch and Neck-scratch[4].Standing on one or both feet,with the trunk inclined obliquely down and the neck entirely stretched,the crane lifts one leg to scratch the head or the neck with the nail of the middle toe.The neck rotates slowly to cater to the scratching of the toe,usually followed by Head-shake or Ruffle-shake(~7.93 s,n=22).

Ⅲ-A-5.Nibble-integuments

Reported by Li(2005)in the Black-necked Crane for the first time[29],two ethons were specified based on the body parts nibbled:

Ⅲ-A-5.1.Nibble-foot(Fig.3-25.)

Standing in tandem,with the neck retracted slightly downwards,the crane nibbles its foot integuments(n=11).

Ⅲ-A-5.2.Nibble-leg(Fig.3-26.)

The crane nibbles the tarsus integuments(n=8).

Ⅲ-A-6.Dangle-leg-care

Standing on one foot with the trunk kept horizontal,the crane bends its neck to remove foreign matter(e.g.,large ice)from the dangling foot.Three ethons were observed and will be displayed solely or grouped at will:

Ⅲ-A-6.1.Dangle-leg-bite(Fig.3-27.)

The crane bites the object repeatedly(n=5).

Ⅲ-A-6.2.Bite-leg-swing(Fig.3-28.)

The crane clenches the object and swings the dangling leg backward to tear the object from the foot(n=1).

Ⅲ-A-6.3.Dangle-leg-strike(Fig.3-29.)

The crane holds the head in a fixed position and lifts the dangling leg horizontally,and then swings the leg forward to strike the object to the bill repeatedly(n=1).

Ⅲ-A-7.Thaw(Fig.3-30.)

Only observed on the wintering grounds when a Black-necked Crane was trying to melt a large “ice fetter” fixed in one tarsus(n=1).In this case,after repeated Dangle-leg-care and Leg-stomp,the crane stood on one foot and tucked the foot under belly coverts for 7 min 20 s and finally removed it.

Ⅲ-A-8.Glide-foot-rub(Fig.3-31.)

Similar to Leg-dangle-glide,but both feet repeatedly rub and hit each other to remove a large lump of slime(n=1).

A-9.Bathe

Five ethons were recorded during bath,and which may be displayed solely or grouped freely during the whole bathing course:

Ⅲ-A-9.1.Bill-slosh(Fig.4-32.)

Standing on both feet,with the trunk inclined slightly down and the neck fairly retracted,the crane dips its bill into the water vertically(only the bill became wet during this ethon),and then lifts up with rapid flicks(~0.74 s,n=24).

Ⅲ-A-9.2.Head-neck-dip(Fig.4-33.)

Standing on both feet,with the trunk inclined slightly or obliquely down(depending on whether the crane was standing on the bank or in the water),the crane dips the head into the water,and then rises up immediately with fast rotations(~2.69 s,n=21).

Ⅲ-A-9.3.Wing-thrash(Fig.4-34.)

With legs bent to “float” on the water,both wings open partially to sides and repeatedly thrash the water surface,and the tail hits the water simultaneously(~2.52 s,n=13).

Ⅲ-A-9.4.Roll-slosh(Fig.4-35.)

Floating on the water,one leg strikes water upward to rotate the trunk to ~45° with the water surface alternatively(“wobbled”),with the opposite wing obliquely folded to side for balance,and the head and neck dip into the water simultaneously(~2.24 s,n=8).

Ⅲ-A-9.5.Belly-slosh(Fig.4-36.)

The crane hits the breast into the water with the bill pointed steeply up,then head lifts immediately with the bill turned to one side to splash water backwards(~3.55 s,n=11).

Ⅲ-A-10.Head-immerse(Fig.4-37.)

Standing on both feet,the crane dips the head into the water slowly and vertically(different from Bill-slosh).After the head is fully immersed,the neck rises at a moderate speed without any rotation or other lateral movement(different from Drink and Head-neck-dip).During the repetition of this ethon,the bill always points to the same place in the water(different from foraging in water).This ethon was only observed once in the breeding area(n=1),when many mosquitos flew around,indicating that its purpose may be to protect the bare cap from bites and to relieve itching with water.

Ⅲ-A-11.Wing-droop

Standing on both feet,the crane droops one or both primaries.This ethon was only observed after bathe as a method of drying feathers(n=2).

Ⅲ-B.ShakeⅢ-B-1.Bill-flick

Similar to Bill-slosh,but this ethon is aimed at eliminating foreign matter from the tip of the bill(~0.27 s,n=43).

Ⅲ-B-2.Head-shake(Fig.5-38.)

Standing on both feet,with the trunk inclined obliquely down and the neck stretched,the head shakes rapidly(~0.56 s,n=36).

Ⅲ-B-3.Ruffle-shake(Fig.5-39.)

Standing on both feet,with the trunk inclined slightly down and the neck retracted slightly,and both wings lifted slightly from the trunk,Black-necked Crane stabs the head downward with fast rotations(~1.50 s,n=29).

Ⅲ-B-4.Ruffle-bow-up(Fig.5-40.)

Standing on both feet,with the trunk kept horizontal and the neck stretched,and the bill pressing body,the crane rapidly shakes the body with wings and tail obliquely elevated(~2.53 s,n=17).

Ⅲ-B-5.Ruffle-bow-down(Fig.5-41.)

Standing on both feet,with the trunk inclined obliquely down and neck retracted fairly,and with both wings opened partially to sides,the crane rapidly shakes its body with feathers extremely fluffed(~2.78 s,n=3).

Ⅲ-B-6.Wing-shake(Fig.5-42.)

Standing on two feet,with the trunk inclined slightly up and the neck retracted slightly,the crane shakes and pats both wings rapidly.This ethon was usually followed by Ruffle-shake and Wing-fold(~1.24 s,n=31).

Ⅲ-B-7.Wing-fold

This ethon usually occurred as an adjustment movement after shaking,stretching and alight,and was also observed during walking or foraging.Both primaries elevate and pat the trunk slightly(~0.19 s,n=57).

Ⅲ-B-8.Tail-wag(Fig.5-43.)

Standing on both feet,with the trunk inclined obliquely or slightly down,the crane elevates both tertiaries to expose the fully fanned rectrices,and usually followed by a rapid horizontal shake(~1.03 s,n=69)

Ⅲ-B-9.Leg-flick(Fig.5-44.)

Standing on one foot,with the trunk slightly inclined down,the crane dangles one leg and swings the tarsus rapidly(~2.76 s,n=33).

Ⅲ-B-10.Leg-stomp(Fig.5-45.)

This was observed when large ice or clay was sticking to the crane’s foot.Similar to Leg-flick,but the tarsus stomps on the ground rapidly and forcefully(~3.21 s,n=11).This behavior would not terminate until the foreign matter is removed,and Dangle-leg-care may occur subsequently if this ethon does not work.

Ⅲ-B-11.Rise-flap(Fig.5-46.)

Standing on both feet,with the trunk inclined upright and the neck stretched,the crane holds both wings widely to sides,and then flaps violently.After ~3.41 s(n=26),the crane lowers head and folds both wings back.The purpose of this behavior could be removing snow or water from its wings,or acting as a preparation movement before leaving the roosting area.

Ⅲ-C.StretchⅢ-C-1.Yawn(Fig.6-47.)

With the trunk inclined slightly up and the neck stretched,the crane repeatedly opens and closes its bill within an amplitude between 30°-35°,and the head turns around simultaneously.After ~5.52 s(n=18),the bill closes and usually is followed by slow blinks.

Ⅲ-C-2.One-leg-stretch(Fig.6-48.)

With the trunk inclined slightly down and the neck retracted fairly,the crane swings one leg backward slowly;the leg is held still when the angle of the tibia and tarsus reached ~135°,and then continues to swing until fully stretched.Holding this posture,the crane inclines its trunk down(~15.60 s,n=25).

Ⅲ-C-3.Side-stretch(Fig.6-49.)

Similar to One-leg-stretch,but the wing of the same side opens widely to side,and the leg doesn’t suspend and hold during stretching.The wing and the leg are fixed after fully stretched for ~10.66 s(n=21).

Ⅲ-C-4.Two-wing-spread-stretch(Fig.6-50.)

Similar to Side-stretch,but both wings open widely to sides(~9.87 s,n=20).

Ⅲ-C-5.Bow-stretch(Fig.6-51.)

Similar to Ruffle-bow-down,but the movement of the wings is performed oddly.Both secondaries elevate vertically and the primaries repeatedly open and close horizontally(~5.98 s,n=6).

Ⅳ.LocomotoryⅣ-A.AmbulatoryⅣ-A-1.Walk-neck-low(Fig.7-52.)

This ethon was commonly observed while searching for food during foraging.With the trunk inclined slightly down,the neck retracted slightly and the bill directed to the ground,the crane walks at a rather low speed,sometimes with eyes scanning the ground ahead(n>100).

Ⅳ-A-2.Walk-neck-mid(Fig.7-53.)

With the trunk basically kept horizontal and the neck retracted fairly,the crane walks at a moderate speed(n>100).

Ⅳ-A-3.Walk-neck-high(Fig.7-54.)

Similar to Walk-neck-mid,but the head is elevated and kept forward,with the neck retracted slightly(n>100).

Ⅳ-A-4.Walk-high-step(Fig.7-55.)

Occurred when Black-necked Crane was walking in the water.With the neck retracted fairly and the head kept forward,the crane walks with the trunk obliquely inclined downward to elevate its belly above the water(n>100).

Ⅳ-A-5.Walk-low-step(Fig.7-56.)

Only observed when Black-necked Crane was passing glacial surfaces.Similar to Walk-neck-mid,but with body feathers fluffed and both wings folded faintly up,the crane steps forward with a small stride length(n>100).

Ⅳ-A-6.Walk-wing-open(Fig.7-57.)

Occurred when Black-necked Crane was passing glacial surfaces.With the trunk inclined backward and both wings opened widely upwards for balance,the crane flapped and walked with a large stride length(n>100).

Ⅳ-B.Run

Similar to the Walk-neck-low,Walk-neck-mid or Walk-neck-high,but the stepping frequency of Run is obviously higher than walking(n>100).

Ⅳ-C.Stride(Fig.8-58.)

Occurred when Black-necked Crane passed through gaps or obstacles in its way.With the head elevated first and both wings opened widely upwards and flapped simultaneously,the crane pushes the ground with one leg and elevates the other to stride over the obstacle(n>100).

Ⅳ-D.Leap

Standing on both feet with the neck retracted fairly,the trunk inclined obliquely down,the crane first bends both legs,and then pushes down on the ground,with the wings opened widely to sides simultaneously,and then jumps vertically off the ground(n>100).

Ⅳ-E.FlightⅣ-E-1.TakeoffⅣ-E-1.1.Run-flap(Fig.8-59.)

The most common way for Black-necked Crane to take off.Standing on both feet,with trunk inclined obliquely up and the neck stretched vertically and slightly arched,the crane keeps the posture called “Preflight Posture”[8],expressing a strong signal of taking off.Then with neck lowered and trunk inclined horizontally,the crane steps forward with a large stride length.At the same time,both wings open widely upwards and flap rapidly with both feet leaving the ground after ~3.21 s(n=41).

Ⅳ-E-1.2.Spring-up(Fig.8-60.)

Usually observed when the runway was short or the wind was strong.The crane springs upwards,both wings flap constantly and then open horizontally to sides for gliding(~0.71s,n=41).

Ⅳ-E-2.Flap & GlideⅣ-E-2.1.Leg-straight(Fig.9-61.)

With the neck stretched horizontally forward,the legs backward and the claws closed,the crane flaps or glides with the body in a nearly straight line(n>100).

Ⅳ-E-2.2 Leg-tuck(Fig.9-62.)

Similar to Leg-straight,but both legs are tucked into the belly feathers for warming bare feet[26](n=16).

Ⅳ-E-2.3.Parachute(Fig.9-63.)

The crane glides(infrequent flapping)with its trunk kept horizontal or slightly inclined backward,neck stretched up,and both legs dangling(n=5).

Ⅳ-E-2.4.Leg-dangle-glide(Fig.9-64.)

Similar to Parachute,but the crane stretches its neck forward while gliding(n>100).

Ⅳ-E-2.5.Trunk-incline-flap(Fig.9-65.)

With the trunk inclined obliquely up(at the angle of ~45°)and the neck stretched horizontally,the crane flaps constantly with both legs bent and dangling(n>100).This was observed during short-distance flight,or occurred as one of the methods to dry the feathers after bathing.

Ⅳ-E-3.Alight(Fig.9-66.)

With both wings stretched out horizontally and legs dangling,the crane erects its trunk and opened the rectrices to slow down(n>100).While landing,the crane lands with both feet first and then steps forward with wings opened widely to sides.When after a short-distance flight or the landing distance is short,the crane would constantly flap its wings for a rapid deceleration.

Ⅳ-F.Swim(Fig.9-67.)

This was only observed once in the breeding area(n=1).With both wings and rectrices lifted,the crane strikes the water alternately with its feet.

Ⅴ.Ingestion,Egestion and ExcretionⅤ-A.ForagingⅤ-A-1.Nibble(Fig.10-68.)

With the neck retracted downward and a quarter of the bill inserted into the soil,the crane opens and closes the bill rapidly with a small amplitude,biting at the clods for insidious potatoes or invertebrates(n>100).

Ⅴ-A-2.Flick(Fig.10-69.)

With the neck retracted downward,the crane inserts and pushes the bill into the soil or presses on various objects,to uncover food beneath(n>100).

Ⅴ-A-3.Stab(Fig.10-70.)

With the trunk inclined forward and the neck stretched down,the crane turns the trunk to dip and stab the opened bill into the water at an angle of ~45°.Occurred when the crane was trying to catch fish in the water(n>100).

Ⅴ-A-4.Peck(Fig.10-71~73.)

Retracting the neck first,the crane stabs the bill towards food rapidly,which was always followed by Toss-Swallow.In addition to pecking objects on the ground,we also recorded the crane pecking icicles on a shrub,spiders on a fence,etc.,and the postures varied with the object pecked(n>100).

Ⅴ-A-5.Bite(Fig.10-74.)

Similar to Nibble,but the bill closes more powerfully with a larger amplitude.Occurred when the crane lifted objects such as potatoes or fish from the ground or water(n>100).

Ⅴ-A-6.Thrash(Fig.10-75.)

Standing on both legs,with the trunk inclined forward and the neck retracted downward,the crane bites an object firmly and repeatedly tugged it off the ground(n>100).

Ⅴ-A-7.Cast(Fig.10-76.)

The crane bites an object and swings the head to cast it out.Occurred in situations such as casting fish to the bank and tossing dirt off the potatoes(n>100).

Ⅴ-A-8.Carry(Fig.10-77.)

Biting an object firmly,the crane transfers food during Walk-neck-low or Walk-neck-mid(n>100).

Ⅴ-A-9.Probe(Fig.10-78.)

Standing on two legs,with the trunk inclined forward and the neck retracted downward,the crane probes the closed bill into food violently(31 times in 19 s).If the food stuck on its bill,the crane would use Head-shake to remove it.Usually,this occurred when the crane was killing a captive fish,but we also recorded a Black-necked Crane having a piece of a potato stuck on its bill,which may indicate that the crane could use this ethon to crack and separate large food.

Ⅴ-A-10.Swill(Fig.10-79.)

Similar to Cast,the crane holds grass and repeatedly immerses and flicks it in water for cleaning food(n=3).

Ⅴ-B.SwallowingⅤ-B-1.Toss-swallow(Fig.11-80.)

The most common ethon used to swallow food.Stretching the neck downward and biting the food,the crane retracts the neck rapidly,and then suddenly stops with the bill opened to swallow food by inertance(n>100).

Ⅴ-B-2.Neck-pumping(Fig.11-81.)

Standing on both feet,with the trunk slightly inclined backward and the neck retracted,the crane stabs rapidly,and then retracts the neck with the food held by the bill,repeating after swallow finished(n>100).Occurred especially when a Black-necked Crane was swallowing large food(e.g.,fish).

Ⅴ-B-3.Drink or Scoop-swallow(Fig.11-82.)

Standing on both legs with the trunk slightly inclined forward and the legs obliquely bent,the crane faintly opens the bill and immerses it in water,and then the bill turns horizontally to fill the mouth with water.Finally,the crane lifts and stretches up the neck with bill slightly opened(~4.05 s,n=57).

Ⅴ-C.Vomit

Only observed one time from a long distance away.The behavior was in highly accordance with the description and illustration by Masatomi on the Hooded CraneGrusmonacha(2004)[4],and included three ethons:bill-shake,gape and vomit(n=1).

Ⅴ-D.Defecate(Fig.11-83.)

Standing on both legs,with the neck slightly retracted,the crane inclines forward and lifts both wings and tail slightly.The trunk lays back after defecating is finished,and sometimes followed by Wing-fold or Tail-wag.This was also observed during flight,in which case the crane usually glided with Leg-straight(n>100).

3 Disscussion

Previous studies have paved the way for current studies on the individual behavior of the crane species[3,4],but until now some issues still remained controversial.Due to continuity and flexibility of the individual(non-social)behaviors,the factitious classification of their behaviors sometimes showed relatively poor applicability in categorizing those multi-functional ethons,leading to repetition and confusion in behavioral classifications.Therefore,based on field observations of the Black-necked Crane,we added to discussions about the individual behaviors of the crane species with this compendium.

According to the behavioral motivations,the repertoire of Ellis et al.(1991)categorized the cranes’ individual behaviors into eight classes,as follows:1)Hatching,2)Posture,3)Sleep-related behavior,4)Sensory-related behavior,5)Maintenance behavior,6)Thermoregulatory and respiratory,7)Locomotory and 8)Ingestion,egestion and excretion[3].Subsequently,from a morphological view,they subdivided these classes into various divisions and sections[3].In this case,vocalizations and “all other ethons relating to both inter-and intra-specific social interactions” were excluded[3].However,here we are inclined to omit I.Hatching from this framework under the same consideration.As one of the most crucial periods during the breeding season,hatching is not a single ethon that is performed alone,but is instead based on the intraspecific relationship among both parents and their immature offspring,which should not be considered as an inanimate object.Hence,we categorized hatching as part of breeding behavior,and then considered it to be a social behavior.Still postures are mostly displayed as the components of other individual or social behaviors,and listing them as a separate group could greatly simplify the repertoire to a great degree.Yet to omit the possible confusion caused by the continuous serial number ahead,we suggest that this item should to be discriminated against following behavior classes.Consequently,we removed the serial number ahead of this item,and more accurately listed it as “Still Posture”(to exclude postures that occur during flight,e.g.Leg-straight,Leg-tuck,etc.).

Sleep-related-behavior(Ⅰ)is a more diverse group than our previous recognition.Taking the closing of the eyelids as the standard,we specified one supplementary ethons-Head-lean-sleep(Ⅰ-C).On the contrary,Head-tuck-watch was omitted from this class because this sensory-related ethon is more likely to be the crane’s observation before or after sleep.

Sensory-related-behavior(Ⅱ)was reintegrated according to the motivation,and was divided into Observe(Ⅱ-A)and Vigilance(Ⅱ-B).The presence of external stimulation determines the crane’s motivation;in other words,the detection is active or passive.The active perception of the environment and other objects or individuals is considered to be Observe,while the passive detection to the environment,as a response to stimulation,is considered to be Vigilance.Observe is part of almost all the behaviors of the crane;as long as the eyelids open,observation will occur.As for Vigilance,three ethons listed by Ellis et al.(1991),Binocular-gaze-low(Ⅱ-B-1),Binocular-gaze-mid(Ⅱ-B-2)and Binocular-gaze-high(Ⅱ-B-3)[3],could be used to accurately estimate the degree of vigilance,even when the crane is lying or in other postures,which would also be applicable in other crane species(e.g.,Hooded Crane).Undeniably,Vigilance may express some social meaning,but considering it helps present a more complete and reasonable repertoire,we still included it in this ethogram.Moreover,Blink and Monocular-gaze,performed as sensory actions(instead of exact ethons or postures),were removed from this ethogram.

Maintenance behavior(Ⅲ)is the most complicated part of the crane’s individual behaviors,which attributes to the multiple functions expressed by some single ethons.Compared to Ellis et al.(1991)[3],at first,we omitted the saying of “comfort behavior,” then briefly classified and named them according to the body form.This simplification is because the item inappropriately gave excessive emphasis to “the behaviors for comforting but not for cleaning,” yet these functions are too complicated and subtle to be separated and elucidated.For example,Shake(Ⅲ-B)could be used to comfort the body and fluff the feathers,but also to remove foreign matters from the body surface.Hence,we divided the Maintenance behavior into three sections,Care of body surface(Ⅲ-A),Shake(Ⅲ-B)and Stretch(Ⅲ-C),and we omitted the ambiguous term “other comfort behavior.”

In the Care of body surface(Ⅲ-A),we omitted Fluff and sleek because it usually emerged as the result of shaking the body.Considering the same motivation of relieving itching,we moved Head-rub(Ⅲ-A-3)together with Scratch(Ⅲ-A-4).Moreover,many new ethons were recorded for the first time:Dangle-leg-care(Ⅲ-A-6)and Thaw(Ⅲ-A-7)were observed to remove large ice from the tarsus;Glide-foot-rub(Ⅲ-A-8)was recorded after the crane took off from the clayed ground,which was also found in the sympatric Common CraneGrusgrus;Head-immerse(Ⅲ-A-10)was only observed once in the breeding ground,and we thought it could be a strategy of the crane to protect its bare cap from mosquitos.

In Shake(Ⅲ-B),due to the similarity in the movements,we moved in the Bill-flick(Ⅲ-B-1),Leg-flick(Ⅲ-B-9)and Rise-flap(Ⅲ-B-11).In the field observations,we noticed that the Black-necked Crane was sensitive to foreign matter on their bill and legs,and this was confirmed with the frequency of these ethons’ occurrence.Leg-stomp(Ⅲ-B-10)was first recorded after a crane was foraging in the clayed ground(n=11),and we thought it was derived from the Leg-flick.Wing-fold(Ⅲ-B-7,n=57)and Tail-wag(Ⅲ-B-8,n=69)were always performed as an adjustment after preening,shaking and stretching,which showed high occurrence frequencies.In Stretch(Ⅲ-C),except for Yawn(Ⅲ-C-1)and Bow-stretch(Ⅲ-C-5),the frequencies of the other three ethons were close(n=25/21/20),always been performed in sequence.Similarly,Wing-thrash(Ⅲ-A-9.3),Roll-slosh(Ⅲ-A-9.4)and Belly-slosh(Ⅲ-A-9.5)were also performed as a successive bathing sequence,showing a close occurrence frequency(n=13/8/11).

We omitted “Thermoregulatory and respiratory” in Ellis’s compendium[3],because the ethons it contains were mostly performed as parts of other behaviors(e.g.,Fluff and Sleek)or were apparent in the change of body features during the display of other ethons(e.g.,Crown-contraction or Crown-expansion).

In Locomotory(Ⅳ),according to the body form while moving,we reclassified Ambulatory(Ⅳ-A).Walk-low-step(Ⅳ-A-5)and Walk-wing-open(Ⅳ-A-6)were recorded as two separate ethons used when passing through the glacial surface,corresponding to different velocities.Stride(Ⅳ-C)was recorded as a new ethon when the crane passed through obstacles or gaps in its way,where the height that the legs were lifted varied with the object size.Ellis et al.(1991)proposed the class of “Transitional action patterns,” but most of these ethons belong to some constant behavior sequences with poor flexibility;thus,we omitted this category and moved these ethons back to their respective behavior sequences.Based on the time sequence of flying,we regrouped and sorted ethons in Flight into three sections,Takeoff(Ⅳ-E-1),Flight(Ⅳ-E-2)and Alight(Ⅳ-E-3).Besides,according to our fieldwork,Leg-tuck(Ⅳ-E-2.2)was rather common on cold mornings in the wintering grounds and stopover sites,we therefore infer that this ethon as one strategy of the black-necked crane to warm bare foot during flight,which was in accordance with Kong et al.(2016)[26].Moreover,during our previous fieldwork,this ethon was also frequently observed other inter-specific individuals,such as Hooded,Red-crowned and Common cranes under similar circumstances.

In Ingestion,Egestion and Excretion(Ⅴ),we sorted the ethons in Foraging according to the time sequence of “searching food-obtaining food-processing food” for the convenience of future supplements.Bill-flick,Bill-push-open and Bill-side-push were listed in the repertoire of Ellis et al.(1991)[3].However,from the practical field observations,these three ethons were always performed as a complex matrix,and their subtle differences were simply reflected in amplitude and direction of the bill.Hence,as mentioned by Masatomi(2004),it may be more appropriate to combine them into Flick(Ⅴ-A-2)[4].Bill-shake,Gape and Vomit were unique and only occurred when the crane intended to spit food from its mouth,so we integrated them into Vomit(Ⅴ-C).Similar to Preflight posture,Defecate(Ⅴ-D)also indicated a strong signal of escape in some situations.

Many of the new ethons were observed in special environmental conditions,such as Winkle(Ⅲ-A-1.2),Dangle-leg-care(Ⅲ-A-6)and Thaw(Ⅲ-A-7)were observed during or after snowy weather;Glide-foot-rub(Ⅲ-A-8)and Leg-stomp(Ⅲ-B-10)were observed after foraging in the clayed ground;Walk-low-step(Ⅳ-A-5)and Walk-wing-open(Ⅳ-A-6)were observed when passing through the glacial surface.Not a single record of these ethons were made without those particular conditions.

As a temporary summary of the individual behaviors of the Black-necked Crane from field observations,we are still faced with many intractable issues,such as the following:behaviors are usually performed on a flexible continuum,so rigid categories have work poorly in clearly distinguishing ambiguous ethons;according to the practical situation the crane confronts,it will adjust the ethon and the actions’ amplitude,frequency,etc.,and possibly add new ethons in fixed behavior sequences to cater to different needs.Hence,what standard should we use to identify and to demarcate these behavioral acts?How can we improve the framework so that we can categorize these ethons without repetition or omission?The questions above may remain through the whole course of ethological study on the crane species,but they will certainly become clearer with the continuous accumulation and discussion of fundamental ethological work.

Acknowledgements

We appreciate He Fenqi,Liu Xiaolong for their advice on the behavior descriptions.We acknowledge Li Bao and Wen Lijia for their contributions in the field observation,and we thank Fengqin Yu,Yangchieh Ts’aijang,Huach’ing Chia,and Lama Chihhua,Kanbo Tashi Sangpo,and Jiangtian Dong for their support in the fieldwork.