室内环境中持久性卤代有机污染物的人体暴露及潜在生殖健康影响

林必桂,于云江,*,陈希超,李良忠,乔静,马瑞雪,向明灯

1. 有机地球化学国家重点实验室,中国科学院广州地球化学研究所,广州 510640 2. 国家环境保护环境污染健康风险评价重点实验室,环境保护部华南环境科学研究所,广州 510655 3. 中国科学院大学,北京 100049 4. 清远市人民医院,清远 511518

环境中的卤代持久性有机污染物(halogenated persistent organic pollutants,Hal-POPs)主要为以下几类[1]:持久性有机氯污染物,主要为有机氯农药(OCPs)和多氯联苯类物质(PCBs);持久性有机溴污染物,主要为溴代阻燃剂,包括多溴联苯醚(PBDEs)、多溴联苯(PBBs)和六溴环十二烷(HBCD)等;持久性氟代有机污染物,主要为全氟有机化合物(PFCs)。Hal-POPs类物质属于全球性有机污染物,广泛存在于各种环境介质中,在环境中不易降解、存留时间较长,具有半挥发性(PFCs类物质除外),并可通过食物链富集,最终影响人类健康。农药生产使用以及电子电器产品生产使用和电子垃圾拆解是我国OCPs、PCBs和PBDEs等Hal-POPs类物质的重要污染来源。我国环境介质中OCPs、PCBs和PBDEs等的监测数据也证实了水体、空气、土壤等环境介质存在不同程度的污染。由于这些Hal-POPs往往也是内分泌干扰物质(endocrine disrupting chemicals,EDCs),因此,它们是威胁人类生殖健康的重要因素之一。为掌握Hal-POPs类物质在人体内的蓄积情况以及产生的危害,其在人体内残留量及其对人体健康的影响研宄已成为近年来科学界关注的热点之一。

人们每天约有80%以上的时间在室内度过,室内环境质量与人体健康密切相关,近10年来有不少研究[2-4]强调了室内环境介质(尤其是室内积尘)摄入有机污染物的重要性,室内的家用电器、纺织品等都会释放多种卤代有机污染物,并通过积尘和空气被摄入人体。研究已经证实,室内环境介质是多溴联苯醚(PBDEs)暴露的主要来源;也是多氯联苯(PCBs)、滴滴涕(DDT)等其他卤代持久性有机污染物(halogenated persistent organic pollutants,Hal-POPs)的重要来源之一[5-6]。因此,室内环境中的Hal-POPs对人体内分泌系统尤其是生殖健康的影响不容忽视,但目前这方面的研究极少。

鉴于室内环境介质是Hal-POPs暴露的主要来源之一,因此开展室内环境中Hal-POPs对人体内分泌系统,尤其是生殖健康的影响研究,对减轻其对人类生殖功能的影响,提高人口素质和生活质量等方面具有重要的意义。本文综述了室内环境介质(包括室内积尘和室内空气)中Hal-POPs的赋存水平及其暴露途径,以及Hal-POPs在人体中的负荷、半衰期及其毒性作用,讨论了Hal-POPs对人体内分泌系统特别是人体生殖健康的影响研究情况,为进一步开展室内环境介质中Hal-POPs对人体内分泌系统尤其是生殖健康影响情况及其可能的机理提供借鉴,并为探讨Hal-POPs的高暴露是否是影响男性生殖健康临床症状的主要原因提供科学依据。

1 室内环境中Hal-POPs的暴露途径、赋存水平以及人体暴露量(Exposure routes, concentrations and human exposure of Hal-POPs in indoor environment)

1.1 室内环境中Hal-POPs的暴露途径

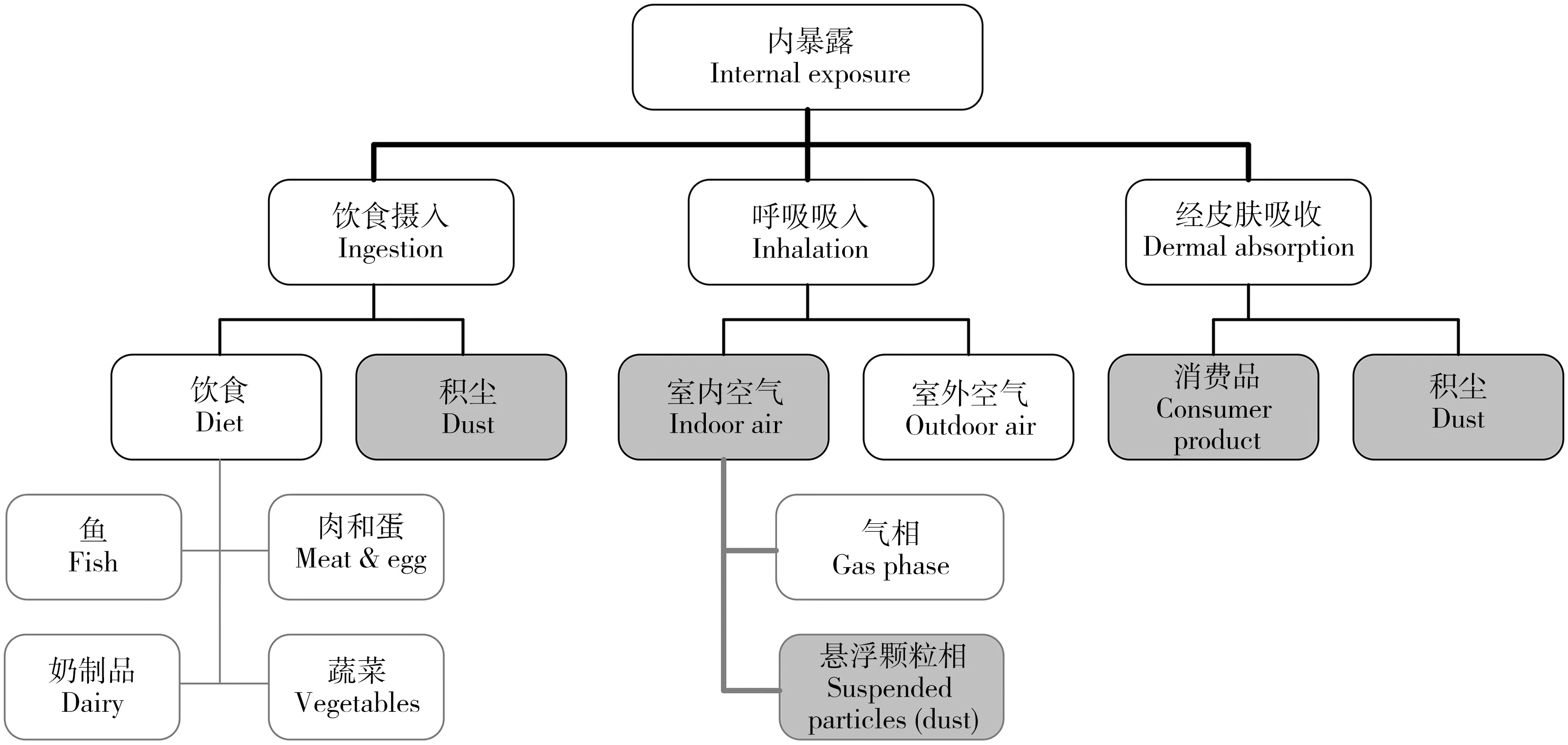

人体Hal-POPs类物质的暴露途径如图1所示,室内环境介质主要包括室内积尘和室内空气。U.S. EPA对室内积尘的定义[7]是:降落在建筑物内部物体表面、地板和地毯等上的颗粒物,可能包括从室外环境带进来的土壤颗粒以及有机物质。室内积尘粒径分布范围较广,从< 2.5 μm到超过2 mm的都有,而且95%以上可能含有机污染物[8]。但是,对于人体暴露而言,重点关注的是粒径<250 μm的积尘,因为这部分积尘容易粘附在手上而被摄入人体[9]。

图1 Hal-POPs的人体暴露途径[16]Fig. 1 Overview of the human exposure pathways which are considered in the present review[16]Note: Consumer products cover a wide range of products e.g. carpets and furniture.

室内空气的暴露途径主要是通过呼吸吸入,空气中大于10 μm的积尘颗粒通常会被鼻子、喉咙或者上呼吸道过滤掉,而小于2.5 μm却能渗透到呼吸系统内,很难去除,而且这些细颗粒经常会含有较高水平的Hal-POPs,对人体健康具有较大的潜在威胁[6]。

已有的研究也表明,室内积尘和室内空气是人体Hal-POPs暴露的主要来源之一[10]。Lorber等[11]对美国人体内PBDEs暴露途径进行了总结,发现饮食暴露只占总暴露的17%,80%的暴露可能是通过室内积尘摄入。在中国,虽然目前尚没有充分的研究证实积尘摄入是PBDEs暴露的最主要途径,但已明确它是主要暴露途径之一[12-13]。Nguyen等[14]调查了越南胡志明市的室内积尘,研究发现室内积尘主要以PBDEs为主,室内空气中主要以PCBs为主,且80%以上为三氯联苯。Harrad等[15]在英国调查居室、公共场所(咖啡店、超市、邮局)等室内环境中空气和积尘样品PCBs的浓度水平,指出室内环境是Hal-POPs暴露的重要场所。此外,电子电器以及塑料等消费品使用时的皮肤接触等也是室内Hal-POPs暴露途径之一。由于人们大部分时间是在室内环境中度过的,因此室内环境的暴露逐渐成为研究热点,引起了较大关注。

影响室内环境介质中化学物质对人体暴露的因素非常复杂,目前对Hal-POPs外暴露与体内负荷之间的关系的研究还非常有限[17]。其中,Bramwell等[18]归纳了影响PBDEs对人体暴露水平的几个主要因素:①相关研究国家淘汰PBDEs生产技术和产品的时间阶段;②PBDEs在人体内的半衰期;③暴露对象在PBDEs污染源及其周边所滞留的时间。这3个因素同样适用于其他Hal-POPs类物质。

1.2 室内环境介质中Hal-POPs的赋存情况及其半衰期

卤代持久性有机污染物(Hal-POPs)是全球性污染物,广泛存在于各种环境介质之中。典型的Hal-POPs(如PCBs、PBDEs、DDT等)大都属于半挥发性物质,在室内空气和室内积尘之间具有一定的迁移规律[19-20]。因此,室内空气中的Hal-POPs赋存量与室内积尘中的赋存量往往具有显著的相关性,其室内积尘中的丰度取决于气态颗粒物的沉降、活动产生的重悬浮、直接富集以及渗透的相互作用[21]。

研究表明,室内空气中Hal-POPs的含量是室外大气中含量的2~20倍以上[22],如加拿大渥太华地区冬天室内的∑10PBDEs(BDE-17, 28, 71, 47, 66, 100, 99, 85, 154, 153)的几何均值为120 pg·m-3,是室外浓度的50倍以上[23]。而不同地区、不同房型的室内空气中Hal-POPs的含量差异很大,如杭州家庭室内空气中PBDEs含量为119 pg·m-3,而办公室含量为194 pg·m-3 [24];英国办公环境室内空气∑5PBDEs (BDE-47, 100, 99, 154, 153)的含量为82~15 509 pg·m-3,而家庭室内空气为60~1 622 pg·m-3[25]。对于室内积尘中的Hal-POPs含量而言,电子垃圾拆解区含量最高,如广东贵屿拆解区的PBDEs含量为900~23 500 ng·g-1[26],PCBs为52~2 900 ng·g-1[27],广东清远拆解区的PBDEs含量为227~160 000 ng·g-1[28],浙江台州拆解区为597~323 919 ng·g-1[29];其次是城市居民区,农村和城市郊区则相对较低。对于不同地区居民室内环境中的Hal-POPs含量而言,美国最高,其次是亚洲国家,而欧洲国家最低[3,30]。

由于之前我国缺乏室内积尘的采集技术规范,因此对于国内不同研究结果而言,室内积尘的赋存水平存在一定的不确定性。2017年,国家环境保护部发布了《环境与健康现场调查技术规范 横断面调查》(HJ 839—2017),首次对室内积尘的采集方法进行了规范,提出:根据实际情况选择擦拭法、刮擦法及便携式吸尘器收集法等方法采集样品,并规范以上各种采集方法。该规范也对室内空气的采集进行了规定,这对今后的室内环境调查提供了依据,使得不同研究结果之间具有更好的可比性。

PCBs、PBDEs 和DDT等Hal-POPs类物质化学性质较为稳定,大多数单体在环境中很难通过物理、化学和生物的方法降解,可以长时间存在于大气、土壤、水和沉积物等环境介质中。已有研究表明,PBDEs 在沉积物、土壤和水中半衰期分别为600 d、150 d和150 d,而在空气中的半衰期为10~20 d[31]。PCBs在环境中的半衰期可长达20年左右[32];而DDT在环境的半衰期可长达30年左右[33]。但关于这些物质在室内积尘中的半衰期研究很少,目前尚无相关数据。

1.3 人体Hal-POPs的暴露量

已有研究表明,灰尘摄入是美国人体PBDEs暴露的主要来源[10];而在我国室内灰尘摄入和膳食是人体PBDEs暴露的主要来源,其次为皮肤暴露,呼吸吸入量相对较小。如广州成人通过膳食和室内积尘摄入的PBDEs量分别为0.27~0.95 和0.20~1.24 ng·kg-1bw·d-1;儿童通过膳食和室内积尘摄入的量分别为0.27~0.46和12.49~14.47 ng·kg-1bw·d-1,通过玩具摄入的量为0.033~0.122 ng·kg-1bw·d-1[34]。Xu等[35]估算了上海成人对家庭室内积尘PBDEs的暴露量为0.283 ng·kg-1bw·d-1,而家庭室内空气TSP的暴露量为0.020 ng·kg-1bw·d-1,其中通过PM2.5的暴露量为0.0081 ng·kg-1bw·d-1,通过室内积尘的暴露量是空气的10倍以上。Zhu等[13]估算了我国各省的室内积尘PBDEs暴露量,其中成人通过积尘摄入量均值为0.53 ng·kg-1bw·d-1,通过皮肤暴露为0.18 ng·kg-1bw·d-1,前者是后者的2.9倍。 Labunska等[36]对浙江台州电子垃圾拆解区的高暴露人群进行估算,发现通过膳食摄入PBDEs的量为1.74 ng·kg-1bw·d-1,其中通过鸡蛋和鸭蛋摄入的量占饮食总暴露量的71.5%;而通过灰尘摄入的量为0.334 ng·kg-1bw·d-1。此外,成人通过接触电子电器产品暴露PBDEs的量要低于通过室内空气的暴露量,而儿童对电子电器及塑料玩具的暴露量要高于其膳食摄入[34]。

一般认为,膳食是PCBs和DDTs等高脂溶性POPs的主要暴露途径,尤其是脂肪含量较高的动物源性食品。Yu等[37]研究结果表明上海地区DDT等有机氯农药的暴露途径以膳食为主,其中膳食暴露占总暴露的95.0%~99.2%,其次为积尘摄入。Wang等[38]估算了台州电子垃圾拆解区居民通过室内积尘和呼吸作用摄入57种PCBs的量分别为0.673和5.73 ng·kg-1bw·d-1,其中通过空气颗粒物吸入的量为1.15 ng·kg-1bw·d-1。Labunska等[39]估算了台州高暴露区成人通过膳食摄入4种高毒性PCBs的量为2.83 pg TEQ·kg-1bw·d-1,而儿童的摄入量为10.22 pg TEQ·kg-1bw·d-1。Yu等[37]估算了上海成人通过膳食、积尘、皮肤接触和呼吸摄入的DDTs的量分别为2.17、0.0085、0.0062和0.0032 ng·kg-1bw·d-1;其中通过空气颗粒物吸入的量为0.0011 ng·kg-1bw·d-1。

由于不同中国学者在进行上述暴露估算时所采用的暴露参数(如体重、肺活量等人体参数以及灰尘摄入量和时间-活动参数等)有所不同,有的采用美国EPA参数,有的采用问卷调查参数,故不同学者所估算的暴露量存在一定的差异。国家环境保护部已于2013出版了《中国人群暴露参数手册》(成人卷和儿童卷(6~17岁)),为我国这方面的研究提供了权威参数,这将使今后该方面的研究结果更具合理性,也使得不同研究结果具有更好的可比性。

2 Hal-POPs在人体中的负荷水平及其半衰期(Load levels and half-lives of Hal-POPs in human body)

2.1 Hal-POPs在人体中的负荷水平

目前关于人体内Hal-POPs负荷的研究主要关注血清、母乳、脐带血等,而对精液的关注则极少。已有的研究结果表明,非职业暴露人群中的母乳、血清、脐带血以及肝脏等组织中的PBDE浓度水平一般在几~几十ng·g-1lw(脂重),而在美国则高达到几百~几千ng·g-1lw,比其他地区高出1~3个数量级,这与美国很高的环境赋存量相一致[3,16]。美国人群血清中总PBDEs浓度是迄今为止报道的最高水平,女性血清中PBDEs中位数浓度为43.3 ng·g-1,男性为25.1 ng·g-1,远远高于亚洲和澳洲人体血清中PBDEs的浓度[40]。日本在2005年对其国内4地采集的89份血清样品进行检测后发现,日本人群血清中PBDEs的几何均数为2.86 ng·g-1,成分以BDE 209为主[41]。Bi等[42]发现在中国电子垃圾拆解区(汕头贵屿)的人体血清中PBDEs含量占Hal-POPs(包括PBDEs、PCB和OCP)总量的46%。

Xing等[43]发现贵屿废旧电器拆解点附近居民母乳中的PCBs毒性当量达到9.5 pg TEQ·g-11ipid,但与发达国家相比 (4.9~57.2 pg TEQ·g-1lipid),我国母乳中多氯联苯的水平还是比较低的。Li等[44]报道了中国12个省市普通人群母乳中多氯联苯等POPs的污染情况,发现工业发达地区母乳中PCBs的毒性当量(2.59~9.92 pg TEQ·g-1lipid)显著高于工业欠发达地区(0.61~3.36 pg TEQ·g-1lipid);而DDT则是我国母乳中最主要的持久性OCP,其浓度为(584.3±362.3) ng·g-1lipid。

Liu等[45]等在电子垃圾拆解区(浙江台州)的人体精液中检测到PBDEs的含量为15.8~86.8 pg·g-1ww(中位值为31.3 pg·g-1ww,湿重),这是首次检测到人体精液中PBDEs含量的报道;而且精液中的含量显著低于血清中的含量53.2~121 pg·g-1ww (中位值72.3 pg·g-1ww)。Weiss等[46]在德国和坦桑尼亚的人体精浆中检测出PCBs的浓度为0.2 ng·g-1lw左右,血清中的浓度是精浆中的3~4倍;人体精浆中的DDT 含量为(0.13±0.05) ng·g-1lw、DDE(DDT体内代谢物)为(0.19±0.06) ng·g-1lw,血清中含量分别为(0.55±0.09) ng·g-1lw和(2.15±1.9) ng·g-1lw,因此血清中DDE的浓度要高出精浆的浓度1个数量级。由于关于精液中Hal-POPs浓度水平的研究非常少,目前关于血清中Hal-POPs浓度与精液中浓度的关联性尚不清楚。

2.2 Hal-POPs在人体中的半衰期

Hal-POPs类物质在人体内具有蓄积性且难以通过代谢排出体外,因此其半衰期是影响人体健康的一个重要因素。已有的研究表明,PCB153在人体中的半衰期约为15年[47],PCB 149/139为1.4年,PCB 84/92为1.4年,PCB 132/161为2年,PCB 174/181为2.4年,PCB 91 和PCB 98/95/93/102为6年,PCB 136为7年[48]。而DDT和它的一些代谢物在人体中的半衰期可长达50年以上[49]。对于PBDEs而言,BDE153在人体中的半衰期最长,约为6.5年左右,BDE47、BDE99、BDE100和BDE154分别约为1.8年、2.9年、1.6年和3.3年,而BDE209为15天[50-51]。对密歇根 PBBs 污染事件中受到高暴露人群近20年的跟踪研究发现,PBBs 在人体血液中的代谢半衰期约为11年[52]。

3 室内环境中Hal-POPs对人体内分泌系统的影响(Effects of Hal-POPs in indoor environment on human endocrine system)

3.1 Hal-POPs对人体的内分泌干扰作用

已有的研究充分表明,PBDEs、PCBs和DDT等Hal-POPs 是内分泌干扰物,可干扰甲状腺激素和性激素[53]。Fraser等[54]通过研究初生儿的体内PBDE负荷情况,发现BMI(身体指数)可能会影响PBDEs的体内负荷,尤其是BDE153。Zhang等[55]通过调查电子垃圾拆解区人群,发现甲状腺激素(T3、T4)与PCBs存在显著的负相关关系。由于PBDEs的分子结构与甲状腺激素T3和T4非常相似,因而一些PBDEs同类物可以增强、降低或模仿甲状腺激素的生物学作用,无论是低溴联苯醚,还是高溴联苯醚的暴露均可以引起甲状腺激素失衡,进而影响其功能[56-57]。但Hal-POPs对性激素及生殖功能(如精液质量)的研究主要还局限于动物实验,对于人体生殖健康的研究则极少[58]。

此外,Hal-POPs在人体内的代谢产物具有多种潜在的毒性。一些研究显示PBDEs代谢物与生物体中某些分子的结合能力比PBDEs的结合能力更强[59-60],如OH-PBDEs是PBDEs 体内代谢物之一,具有多种潜在的毒性,如抗雌激素毒性,神经毒性[61],干扰甲状腺荷尔蒙动态平衡[62],影响雌二醇合成[22-24],类雌激素毒性[63]等,另外由于氢氧基的代谢产物与甲状腺荷尔蒙输送蛋白有很高的亲和性,更容易与甲状腺荷尔蒙接受体TRα1和TRβ1相结合;OH-PBDEs 某些毒性甚至超过 PBDEs 母体本身[64]。OH-PCBs以及DDT的代谢物(DDE和DDD)有的比其母体的毒性也更大[65-68]。

3.2 室内环境介质中Hal-POPs的赋存水平与人体内负荷的相关性研究

关于室内积尘中Hal-POPs对人体健康的影响研究,目前主要是根据相关的人体暴露参数来估算每日摄入量并评估其健康风险[27-28]。其次是分析积尘中Hal-POPs的赋存水平与人体体内负荷之间的关联性,如Karlsson等[69]发现人体血清中PBDEs的浓度与室内积尘的浓度存在正相关性;Bramwell等[18]发现积尘中五溴联苯醚(Penta-BDE)与人体体内的负荷具有显著正相关性。Wu等[70]的研究表明,人体母乳中PBDEs的含量与室内积尘显著正相关。在比利时人体血清中,六溴环十二烷(HBCD)的浓度与积尘而不是膳食呈显著正相关[71]。Bramwell等[18]通过总结历年(截止至2015年)所发表的关于人体体内PBDEs负荷与室内积尘摄入和饮食摄入的相关性研究,指出Penta-BDE在人体内的负荷与在积尘中的赋存水平具有显著的正相关性。目前关于室内环境空气中的Hal-POPs对人体健康的影响研究极少,主要局限于利用暴露模型分析其赋存水平对人体健康的风险评估[72]。上述研究表明,室内环境介质中Hal-POPs的赋存水平与其在人体内的负荷水平存在相关性,因此室内环境中Hal-POPs对人体的内分泌干扰作用不容忽视。

4 室内环境中Hal-POPs对男性生殖健康的影响(Effects of Hal-POPs in indoor environment on male reproductive health)

4.1 人体内Hal-POPs负荷水平及其与男性生殖健康的关系

男性生殖功能正常与否主要体现在精液质量上,男性精液质量低下是夫妇不育的重要原因之一。2009年中国不育不孕调查结果显示,我国一年不孕症的发生率已达到15%~20%,而45%以上的不孕与男性原因有关,其中又有45%~70%与精子质量低下有关[73]。在过去的近20年间,精子质量下降问题一直是医疗卫生界的重要议题之一,同时人们已经注意到环境因素可能是威胁男性生殖功能的元凶[74-75]。而环境内分泌干扰物由于能模拟、强化或抑制激素作用,即使数量极少,也可能对人体生殖发育等产生影响,因此最受到广泛关注[76-78]。

目前,关于Hal-POPs对男性生殖健康的影响研究主要关注血清中Hal-POPs负荷水平与精子质量(精子数量、精子密度、精子运动率、精子正常形态率等)之间的相关性,而对其作用机理的研究非常有限。Pflieger-Bruss等[79]发现PCBs存在于与生殖有关的体液中(如卵泡液和精液),大部分PCBs的作用是通过芳香烃受体(如精子)来实现的。Emmett 等[80]的研究结果表明PCBs会造成男性精子数量减少。不孕人群精浆中低浓度DDT和DDE不影响精液质量,然而血浆高浓度DDT降低精子活动力和存活率,增加精子尾部缺陷比例[46];人体精液量、精子前向运动率随p,p’-DDE的增高而降低,少精症和弱精症的发生率与p,p’-DDE浓度呈正相关[81]。Akutsu等[82]发现人体血清中的BDE-153含量水平与精子浓度和睾丸大小成负相关关系。Abdelouahab等[83]发现成年人血清中的BDE-47、BDE-100和∑BDE与精子活动率成负相关性,与其他精子指标不呈显著相关性;血清甲状腺激素水平与BDE-47、BDE-99、∑BDE和p,p’-DDE成负相关性,而与PCBs成正相关性,该研究为PBDEs可能干扰普通人群的精子质量和甲状腺激素水平提供了进一步的佐证。此外,有研究表明室内环境中的Hal-POPs赋存水平与体内的性激素等内分泌物质具有相关性,如Meeker等[84]发现室内积尘中PBDE含量与人体体内黄体生成素(LH)和卵泡刺激素(FSH)显著负相关,并与抑制素B和性激素结合球蛋白(SHBG)呈显著正相关关系;而体内的PBDEs负荷与游离T4也呈正相关关系。因此,室内环境中的Hal-POPs对男性内分泌系统尤其是男性生殖健康的影响不容忽视。

4.2 室内环境中Hal-POPs对男性生殖健康影响机理的探讨

男性内分泌系统主要由男性睾丸、脑垂体、甲状腺、肾上腺组成,该系统有效控制着整个生物过程,包括大脑发育、神经系统、生殖系统、代谢和血糖浓度[73]。男性的下丘脑-垂体-睾丸轴组成一闭合性负反馈调节机制,是维持男性正常生殖功能的主要调节机制;其他一些内分泌腺轴,如肾上腺和甲状腺等也可通过改变下丘脑-垂体-睾丸轴的功能而对精子产生影响。因此,通过准确测定生殖激素,有助于评价下丘脑-垂体-睾丸轴的功能,并对下丘脑-垂体-睾丸轴功能障碍进行精确的定位[85]。

环境因素对男性生育力的影响主要通过2种途径:一是作用于下丘脑-垂体-性腺轴,导致对性腺轴刺激减退,影响精子的发生和性激素的产生,从而引起男子不育和男子性功能障碍;二是直接作用睾丸,影响睾丸的支持细胞和精子发生过程,造成可回复性或永久性剩余障碍[86]。室内环境中的Hal-POPs属于环境内分泌干扰物(EDCs),具有类似雌激素作用,或能够干扰正常雄激素、甲状腺激素,能够激活或抑制体内激素合成与代谢,因此其对男性生殖健康的影响机理以第一种路径为主。但目前只有少数学者通过流行病学手段去研究Hal-POPs与男性生殖健康之间的关系,其临床症状是否来源于Hal-POPs的高暴露仍然存在争议[41],如Vitku等[87]在不孕症门诊研究中(191例)发现血清6种PCBs (CB-28, 101, 118, 138, 153, 180)总浓度与男性睾酮、游离睾酮、游离雄激素指数和双氢睾酮等雄性激素成负相关关系,但未发现环境中的PCBs与精子质量存在相关性关系。而且,已有的研究主要关注Hal-POPs对人体甲状腺激素的影响,因此今后的研究应重视对其他性激素(包括睾酮、促黄体生成素、促卵泡激素、雌二醇等)的影响,进而精确探明其对下丘脑-垂体-睾丸轴功能障碍的作用机制,从而深入探索Hal-POPs男性生殖健康的影响机理。

5 结论和展望(Conclusion and prospects)

根据上述已有研究结果可知, Hal-POPs在室内环境(包括室内积尘和室内空气)中的赋存水平与在人体体内的负荷水平存在相关性关系;而体内Hal-POPs的负荷水平与人体的甲状腺激素和性激素水平以及男性精液质量也存在相关性关系,故Hal- POPs对人体内分泌系统尤其是男性生殖系统的潜在健康风险值得关注。有关从男性精液中检出 PCBs、DDT和PBDEs等Hal-POPs的报道,进一步为Hal- POPs可进入男性生殖系统并影响其生殖发育的认识提供了支持。因此,关于室内环境中Hal-POPs对人体内分泌系统尤其是男性生殖健康的影响情况、具体的暴露途径及其影响机理亟待研究。

关于这方面的研究应需要关注以下几个方面:①室内环境介质对人体的具体暴露途径和暴露量需要进一步研究;②进入人体体内颗粒物的生物有效性需要进一步研究。③需深入探索室内环境介质中Hal-POPs对人体生殖健康的机理方面,尤其是体内Hal-POPs负荷对性激素含量的影响;④由于影响人体生殖健康的影响因子非常多,且外源性激素对人体内分泌系统尤其是男性生殖系统的研究非常复杂,因此需要从流行病学角度对这一课题进行大量的调查研究。

[1] Meng G, Nie Z Q, Feng Y, et al. Typical halogenated persistent organic pollutants in indoor dust and the associations with childhood asthma in Shanghai, China [J]. Environmental Pollution, 2016, 211: 389-398

[2] Jones-Otazo H A, Clarke J P, Diamond M L, et al. Is house dust the missing exposure pathway for PBDEs? An analysis of the urban fate and human exposure to PBDEs [J]. Environmental Science and Technology, 2005, 39(14): 5121-5130

[3] Yu G, Bu Q W, Cao Z G, et al. Brominated flame retardants (BFRs): A review on environmental contamination in China [J]. Chemosphere, 2016, 150: 479-490

[4] Kim S K, Kim K S, Hong S. Overview on relative importance of house dust ingestion in human exposure to polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs): International comparison and Korea as a case [J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2016, 571: 82-91

[5] de Boer J, Ballesteros-Gomez A, Leslie H A, et al. Flame retardants: Dust-and not food - might be the risk [J]. Chemosphere, 2016, 150: 461-464

[6] Harrad S, de Wit C A, Abdallah M A-E, et al. Indoor contamination with hexabromocyclododecanes, polybrominated diphenyl ethers, and perfluoroalkyl compounds: An important exposure pathway for people? [J]. Environmental Science and Technology, 2010, 44(9): 3221-3231

[7] US EPA. Exposure Factors Handbook: Chapter 5 Soil and Dust Ingestion [M]. Washington DC: US Environmental Protection Agency, 2011:2

[8] Morawska L, Salthammer T. Indoor Environment: Airborn Particles and Setted Dust [M]. WILEY-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA., 2003: 143-144

[9] Yamamoto N, Takahashi Y, Yoshinaga J, et al. Size distributions of soil particles adhered to children's hands [J]. Archives of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology, 2006, 51(2): 157-163

[10] Betts K S. Unwelcome guest: PBDEs in indoor dust [J]. Environmental Health Perspectives, 2008, 116(5): A202-A208

[11] Lorber M. Exposure of Americans to polybrominated diphenyl ethers [J]. Journal of Exposure Science and Environmental Epidemiology, 2008, 18(1): 2-19

[12] Yu Y X, Pang Y P, Li C, et al. Concentrations and seasonal variations of polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs) in in- and out-house dust and human daily intake via dust ingestion corrected with bioaccessibility of PBDEs [J]. Environment International, 2012, 42: 124-131

[13] Zhu N Z, Liu L Y, Ma W L, et al. Polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs) in the indoor dust in China: Levels, spatial distribution and human exposure [J]. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety, 2015, 111: 1-8

[14] Nguyen Minh T, Takahashi S, Suzuki G, et al. Contamination of indoor dust and air by polychlorinated biphenyls and brominated flame retardants and relevance of non-dietary exposure in Vietnamese informal e-waste recycling sites [J]. Environment International, 2013, 51: 160-167

[15] Harrad S, Hazrati S, Ibarra C. Concentrations of polychlorinated biphenyls in indoor air and polybrominated diphenyl ethers in indoor air and dust in Birmingham, United Kingdom: Implications for human exposure [J]. Environmental Science and Technology, 2006, 40(15): 4633-4638

[16] Frederiksen M, Vorkamp K, Thomsen M, et al. Human internal and external exposure to PBDEs - A review of levels and sources [J]. International Journal of Hygiene and Environmental Health, 2009, 212(2): 109-134

[17] Song Q B, Li J H. A systematic review of the human body burden of e-waste exposure in China [J]. Environment International, 2014, 68: 82-93

[18] Bramwell L, Glinianaia S V, Rankin J, et al. Associations between human exposure to polybrominated diphenyl ether flame retardants via diet and indoor dust, and internal dose: A systematic review [J]. Environment International, 2016, 92-93: 680-694

[19] Wei W, Mandin C, Blanchard O, et al. Distributions of the particle/gas and dust/gas partition coefficients for seventy-two semi-volatile organic compounds in indoor environment [J]. Chemosphere, 2016, 153: 212-219

[20] Wilford B H, Shoeib M, Harner T, et al. Polybrominated diphenyl ethers in indoor dust in Ottawa, Canada: Implications for sources and exposure [J]. Environmental Science and Technology, 2005, 39(18): 7027-7035

[21] Fromme H, Koerner W, Shahin N, et al. Human exposure to polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDE), as evidenced by data from a duplicate diet study, indoor air, house dust, and biomonitoring in Germany [J]. Environment International, 2009, 35(8): 1125-1135

[22] Hamers T, Kamstra J H, Sonneveld E, et al. Biotransformation of brominated flame retardants into potentially endocrine-disrupting metabolites, with special attention to 2,2 ',4,4 '-tetrabromodiphenyl ether (BDE-47) [J]. Molecular Nutrition and Food Research, 2008, 52(2): 284-298

[23] Wilford B H, Harner T, Zhu J P, et al. Passive sampling survey of polybrominated diphenyl ether flame retardants in indoor and outdoor air in Ottawa, Canada: Implications for sources and exposure [J]. Environmental Science and Technology, 2004, 38(20): 5312-5318

[24] Sun J Q, Wang Q W, Zhuang S L, et al. Occurrence of polybrominated diphenyl ethers in indoor air and dust in Hangzhou, China: Level, role of electric appliance, and human exposure [J]. Enviromental Pollution, 2016, 218: 942-949

[25] Harrad S, Wijesekera R, Hunter S, et al. Preliminary assessment of UK human dietary and inhalation exposure to polybrominated diphenyl ethers [J]. Environmental Science and Technology, 2004, 38(8): 2345-2350

[26] Zheng J, Luo X J, Yuan J G, et al. Levels and sources of brominated flame retardants in human hair from urban, e-waste, and rural areas in South China [J]. Environmental Pollution, 2011, 159(12): 3706-3713

[27] Wang J, Ma Y-J, Chen S-J, et al. Brominated flame retardants in house dust from e-waste recycling and urban areas in South China: Implications on human exposure [J]. Environment International, 2010, 36(6): 535-541

[28] Zheng X, Xu F, Chen K, et al. Flame retardants and organochlorines in indoor dust from several e-waste recycling sites in South China: Composition variations and implications for human exposure [J]. Environment International, 2015, 78: 1-7

[29] Leung A O W, Zheng J, Yu C K, et al. Polybrominated diphenyl ethers and polychlorinated dibenzo-p-dioxins and dibenzofurans in surface dust at an e-waste processing site in southeast China [J]. Environmental Science and Technology, 2011, 45(13): 5775-5782

[30] Frederiksen M, Vorkamp K, Thomsen M, et al. Human internal and external exposure to PBDEs—A review of levels and sources [J]. International Journal of Hygiene and Environmental Health, 2009, 212(2): 109-134

[31] Palm A, Cousins I T, Mackay D, et al. Assessing the environmental fate of chemicals of emerging concern: A case study of the polybrominated diphenyl ethers [J]. Environmental Pollution, 2002, 117(2): 195-213

[32] Shipley H J, Sokoly D, Johnson D W. Historical data review and source analysis of PCBs/Arochlors in the Lower Leon Creek Watershed [J]. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment, 2017, 189(2): 75

[33] Mansouri A, Cregut M, Abbes C, et al. The environmental issues of DDT pollution and bioremediation: A multidisciplinary review [J]. Applied Biochemistry and Biotechnology, 2017, 181(1): 309-339

[34] Ni K, Lu Y, Wang T, et al. A review of human exposure to polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs) in China [J]. International Journal of Hygiene and Environmental Health, 2013, 216(6): 607-623

[35] Xu F, Tang W B, Zhang W, et al. Levels, distributions and correlations of polybrominated diphenyl ethers in air and dust of household and workplace in Shanghai, China: Implication for daily human exposure [J]. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 2016, 23(4): 3229-3238

[36] Labunska I, Harrad S, Wang M, et al. Human dietary exposure to PBDEs around E-waste recycling sites in Eastern China [J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2014, 48(10): 5555-5564

[37] Yu Y, Li C, Zhang X, et al. Route-specific daily uptake of organochlorine pesticides in food, dust, and air by Shanghai residents, China [J]. Environment International, 2012, 50: 31-37

[38] Wang Y, Hu J, Lin W, et al. Health risk assessment of migrant workers' exposure to polychlorinated biphenyls in air and dust in an e-waste recycling area in China: Indication for a new wealth gap in environmental rights [J]. Environment International, 2016, 87: 33-41

[39] Labunska I, Abdallah M A-E, Eulaers I, et al. Human dietary intake of organohalogen contaminants at e-waste recycling sites in Eastern China [J]. Environment International, 2015, 74 (Supplement C): 209-220

[40] Schecter A, Papke O, Tung K C, et al. Polybrominated diphenyl ether flame retardants in the US population: Current levels, temporal trends, and comparison with dioxins, dibenzofurans, and polychlorinated biphenyls [J]. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 2005, 47(3): 199-211

[41] Inoue K, Harada K, Takenaka K, et al. Levels and concentration ratios of polychlorinated biphenyls and polybrominated diphenyl ethers in serum and breast milk in Japanese mothers [J]. Environmental Health Perspectives, 2006, 114(8): 1179-1185

[42] Bi X, Thomas G O, Jones K C, et al. Exposure of electronics dismantling workers to polybrominated diphenyl ethers, polychlorinated biphenyls, and organochlorine pesticides in South China [J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2007, 41(16): 5647-5653

[43] Xing G H, Chan J K Y, Leung A O W, et al. Environmental impact and human exposure to PCBs in Guiyu, an electronic waste recycling site in China [J]. Environment International, 2009, 35(1): 76-82

[44] Li J, Zhang L, Wu Y, et al. A national survey of polychlorinated dioxins, furans (PCDD/Fs) and dioxin-like polychlorinated biphenyls (dl-PCBs) in human milk in China [J]. Chemosphere, 2009, 75(9): 1236-1242

[45] Liu P Y, Zhao Y X, Zhu Y Y, et al. Determination of polybrominated diphenyl ethers in human semen [J]. Environment International, 2012, 42: 132-137

[46] Weiss J M, Bauer O, Bluethgen A, et al. Distribution of persistent organochlorine contaminants in infertile patients from Tanzania and Germany [J]. Journal of Assisted Reproduction and Genetics, 2006, 23(9-10): 393-399

[47] Quinn C L, Wania F. Understanding differences in the body burden-age relationships of bioaccumulating contaminants based on population cross sections versus individuals [J]. Environmental Health Perspectives, 2012, 120(4): 554-559

[48] Kania-Korwel I, Lehmler H-J. Toxicokinetics of chiral polychlorinated biphenyls across different species—A review [J]. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 2016, 23(3): 2058-2080

[49] Younglai E V, Foster W G, Hughes E G, et al. Levels of environmental contaminants in human follicular fluid, serum, and seminal plasma of couples undergoinginvitrofertilization [J]. Archives of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology, 2002, 43(1): 121-126

[50] Gyalpo T, Toms L M, Mueller J F, et al. Insights into PBDE uptake, body burden, and elimination gained from Australian age-concentration trends observed shortly after peak exposure [J]. Environmental Health Perspectives, 2015, 123(10): 978-984

[51] Thuresson K, Hoglund P, Hagmar L, et al. Apparent half-lives of hepta- to decabrominated diphenyl ethers in human serum as determined in occupationally exposed workers [J]. Environmental Health Perspectives, 2006, 114(2): 176-181

[52] Rosen D H, Flanders W D, Friede A, et al. Half-life of polybrominated biphenyl in huaman sera [J]. Environmental Health Perspectives, 1995, 103(3): 272-274

[53] Legler J, Brouwer A. Are brominated flame retardants endocrine disruptors? [J]. Environment International, 2003, 29(6): 879-885

[54] Fraser A J, Webster T F, McClean M D. Diet contributes significantly to the body burden of PBDEs in the general US population [J]. Environmental Health Perspectives, 2009, 117(10): 1520-1525

[55] Zhang J, Jiang Y, Zhou J, et al. Elevated body burdens of PBDEs, dioxins, and PCBs on thyroid hormone homeostasis at an electronic waste recycling site in China [J]. Environmental Science and Technology, 2010, 44(10): 3956-3962

[56] Zheng J, He C-T, Chen S-J, et al. Disruption of thyroid hormone (TH) levels and TH-regulated gene expression by polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs), polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), and hydroxylated PCBs in e-waste recycling workers [J]. Environment International, 2017, 102: 138-144

[57] Jacobson M H, Barr D B, Marcus M, et al. Serum polybrominated diphenyl ether concentrations and thyroid function in young children [J]. Environmental Research, 2016, 149: 222-230

[58] Lyche J L, Rosseland C, Berge G, et al. Human health risk associated with brominated flame-retardants (BFRs) [J]. Environment International, 2015, 74: 170-180

[59] Kitamura S, Shinohara S, Iwase E, et al. Affinity for thyroid hormone and estrogen receptors of hydroxylated polybrominated diphenyl ethers [J]. Journal of Health Science, 2008, 54(5): 607-614

[60] Kojima H, Takeuchi S, Uramaru N, et al. Nuclear hormone receptor activity of polybrominated diphenyl ethers and their hydroxylated and methoxylated metabolites in transactivation assays using Chinese hamster ovary cells [J]. Environmental Health Perspectives, 2009, 117(8): 1210-1218

[61] Dingemans M M L, de Groot A, van Kleef R G D M, et al. Hydroxylation increases the neurotoxic potential of BDE-47 to affect exocytosis and calcium homeostasis in PC12 cells [J]. Environmental Health Perspectives, 2008, 116(5): 637-643

[62] Ucan-Marin F, Arukwe A, Mortensen A, et al. Recombinant transthyretin purification and competitive binding with organohalogen compounds in two gull species (LarusargentatusandLarushyperboreus) [J]. Toxicological Sciences, 2009, 107(2): 440-450

[63] Legler J. New insights into the endocrine disrupting effects of brominated flame retardants [J]. Chemosphere, 2008, 73(2): 216-222

[64] Canton R F, Scholten D E A, Marsh G, et al. Inhibition of human placental aromatase activity by hydroxylated polybrominated diphenyl ethers (OH-PBDEs) [J]. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology, 2008, 227(1): 68-75

[65] Otake T, Yoshinaga J, Enomoto T, et al. Thyroid hormone status of newborns in relation to in utero exposure to PCBs and hydroxylated PCB metabolites [J]. Environmental Research, 2007, 105(2): 240-246

[66] Guo Z, Qiu H, Wang L, et al. Association of serum organochlorine pesticides concentrations with reproductive hormone levels and polycystic ovary syndrome in a Chinese population [J]. Chemosphere, 2017, 171: 595-600

[67] He C-T, Yan X, Wang M-H, et al. Dichloro-diphenyl-trichloroethanes (DDTs) in human hair and serum in rural and urban areas in South China [J]. Environmental research, 2017, 155: 279-286

[68] Thomas A, Toms L-M L, Harden F A, et al. Concentrations of organochlorine pesticides in pooled human serum by age and gender [J]. Environmental Research, 2017, 154: 10-18

[69] Karlsson M, Julander A, van Bavel B, et al. Levels of brominated flame retardants in blood in relation to levels in household air and dust [J]. Environment International, 2007, 33(1): 62-69

[70] Wu N, Herrmann T, Paepke O, et al. Human exposure to PBDEs: Associations of PBDE body burdens with food consumption and house dust concentrations [J]. Environmental Science and Technology, 2007, 41(5): 1584-1589

[71] Roosens L, Abdallah M A E, Harrad S, et al. Exposure to hexabromocyclododecanes (HBCDs) via dust ingestion, but not diet, correlates with concentrations in human serum: Preliminary results [J]. Environmental Health Perspectives, 2009, 117(11): 1707-1712

[72] Chen L, Mai B, Xu Z, et al. In- and outdoor sources of polybrominated diphenyl ethers and their human inhalation exposure in Guangzhou, China [J]. Atmospheric Environment, 2008, 42(1): 78-86

[73] 高尔生. 精液质量与生殖健康[M]. 上海: 复旦大学出版社, 2013: 1-2, 170

Gao E S. Semen Quality and Reproductive Health [M]. Shanghai: Fudan University Press, 2013: 1-2, 170 (in Chinese)

[74] Stefankiewicz J, Kurzawa R, Drozdzik M. Environmental factors disturbing fertility of men [J]. Ginekologia Polska, 2006, 77(2): 163-169

[75] Oliva A, Spira A, Multigner L. Contribution of environmental factors to the risk of male infertility [J]. Human Reproduction (Oxford, England), 2001, 16(8): 1768-1776

[76] Hauser R, Altshul L, Chen Z Y, et al. Environmental organochlorines and semen quality: Results of a pilot study [J]. Environmental Health Perspectives, 2002, 110(3): 229-233

[77] Hauser R, Chen Z Y, Pothier L, et al. The relationship between human semen parameters and environmental exposure to polychlorinated biphenyls and p,p'-DDE [J]. Environmental Health Perspectives, 2003, 111(12): 1505-1511

[78] Hauser R, Williams P, Altshul L, et al. Evidence of interaction between polychlorinated biphenyls and phthalates in relation to human sperm motility [J]. Environmental Health Perspectives, 2005, 113(4): 425-430

[79] Pflieger-Bruss S, Hagemann S, Korner W, et al. Effects of single non-ortho, mono-ortho, and di-ortho chlorinated biphenyls on human sperm functionsinvitro[J]. Reproductive Toxicology, 2006, 21(3): 280-284

[80] Emmett E A, Maroni M, Jefferys J, et al. Studies of transformer repair workers exposed to PCBs: II. Results of clinical laboratory investigations [J]. American Journal of Industrial Medicine, 1988, 14(1): 47-62

[81] Aneck-Hahn N H, Schulenburg G W, Bornman M S, et al. Impaired semen quality associated with environmental DDT exposure in young men living in a malaria area in the Limpopo Province, South Africa [J]. Journal of Andrology, 2007, 28(3): 423-434

[82] Akutsu K, Takatori S, Nozawa S, et al. Polybrominated diphenyl ethers in human serum and sperm quality [J]. Bulletin of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology, 2008, 80(4): 345-350

[83] Abdelouahab N, AinMelk Y, Takser L. Polybrominated diphenyl ethers and sperm quality [J]. Reproductive Toxicology, 2011, 31(4): 546-550

[84] Meeker J D, Johnson P I, Camann D, et al. Polybrominated diphenyl ether (PBDE) concentrations in house dust are related to hormone levels in men [J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2009, 407(10): 3425-3429

[85] 熊承良, 商学军, 刘继红. 人类精子学[M]. 北京: 人民卫生出版社, 2013: 353

Xiong C L, Shang X J, Liu J H. Human Spermatology [M]. Beijing: People's Medical Publishing House, 2013: 353 (in Chinese)

[86] Rozati R, Reddy P P, Reddanna P, et al. Role of environmental estrogens in the deterioration of male factor fertility [J]. Fertility and Sterility, 2002, 78(6): 1187-1194

[87] Vitku J, Heracek J, Sosvorova L, et al. Associations of bisphenol A and polychlorinated biphenyls with spermatogenesis and steroidogenesis in two biological fluids from men attending an infertility clinic [J]. Environment International, 2016, 89-90: 166-173