西方大学建筑教育空间概述

——类型与室内组织

和马町

尚晋 译

西方大学建筑教育空间概述

——类型与室内组织

和马町

尚晋 译

教育空间在建筑领域中是一种特别的类型。空间在其中可以成为表达教育理念的手段之一。本文简要概括了西方大学建筑教育空间的演变,并通过学校建筑的设计类型及其室内组织表明建筑教学的思想。本文据此分为两部分:首先回顾这种建筑类型的演变,概括西方世界建筑学校的设计史。然后按时间顺序展示以自身建筑表达教育理念的学校类型,或是学校的建筑启发了教育思想的案例。本文的出发点是唐纳德·舍恩的理论:社会是一个持续变化的过程,而教学体系会反映出与之相关的变化。对西方大学建筑教育空间的概括表明,教学体系的演变是后续建筑理念和教学原则导致的。在这一过程中,新思想取代了旧教条。其次,在概述之后将简要考查专门表达教学方法的空间思想的室内元素,然后再通过选例进行对比。最后,总结可以从中提炼的内容。

建筑设计空间,建筑教育,教育设计,建筑类型,工作室设计,评图空间

1 绪言

首先要说明的是,这样一篇短文是不可能涵盖完整的建筑教育空间设计史的。因为这个设计史跨越了数个世纪,并且其中的许多学校和建筑都有独特的发展历程。所以本文的意图不在于完整的设计史,而是集中概括挑选出来的学校和相应的教育建筑类型,专门论述它们的空间特征。出人意料的是,培养建筑师的空间设计并没有深入的研究。关于建筑设计教育[1-2]以及培养建筑师的课程设置[3-4]的研究不胜枚举,然而对于一个以“创造三维空间并将其用于相关的人类活动”[1]为首要目标的学科来说,自身的学科应有怎样的空间竟没有透彻的研究。这种学术资源的匮乏不能用缺少研究材料来解释,事实上有大量专门为建筑教育设计的建筑。建筑师与其机构共同努力创造了针对这些学校建筑教育理念的特殊建筑类型,或者反之从建筑上创造了新的理念。因此,本文将从选择这些案例开始,并尝试把各种探索纳入一个对比研究中1)。然后从这种概括中提炼出关于建筑类型和空间组织的观点。

2 研究方法

本文的研究方法是先对比分析案例研究,对建筑学校设计选例按时间顺序进行梳理。案例研究的方法源自社会科学领域[5],并广泛用于面向实践的领域,比如环境研究、建筑学和商业研究。案例研究对于特定对象的描述和分析尤为有效[6],并能展开多方面的深入考察[7]。一般来说,案例研究的目的是通过分析一个或多个案例来研究复杂的现象。所以,案例研究一般被认为是“一种宏观现象的实例,一组类似实例的一部分”[7]。不过,凭借对一个具体案例的详细考察很难证明该案例的结论与情况相似或相反的其他案例之间的关系。所以就本文而言更合适的方法是,在一个总体系中提供多种案例,然后再对同一起源的各种反应进行对比分析。虽然更多的案例可以带来更全面的概括,但本文的研究所能挑选的案例数量有限,所以作者的选择将限定在那些通过建筑明确表达教学理念,或是某个学校的建筑启发了一种特定教学思想的案例。本文的另一个目的是从建筑学校的整个历史中挑选案例。

3 建筑类型概况

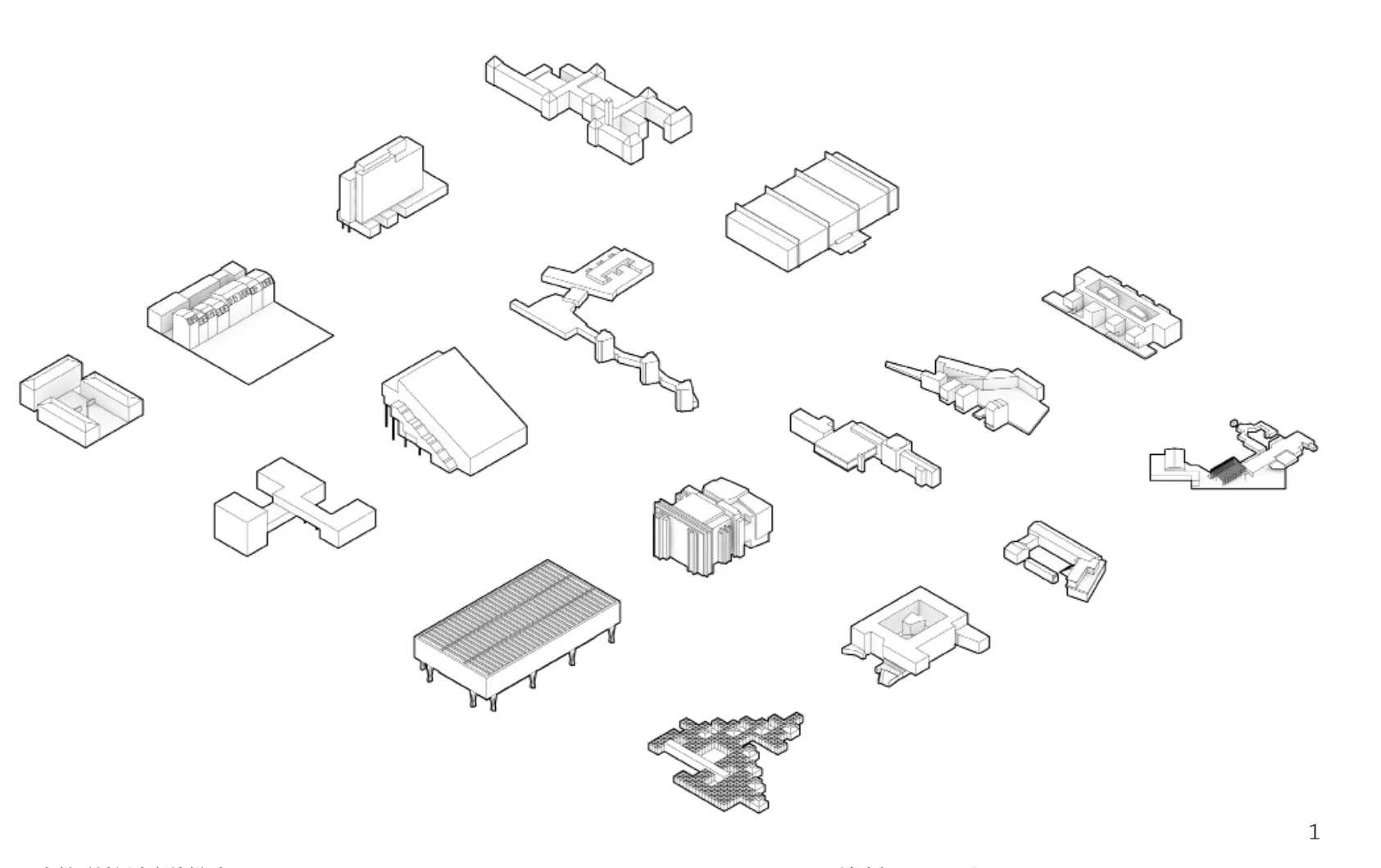

按照唐纳德·舍恩的理论[2],社会处在持续变化的过程中,教学体系会反映与之有关的变化。本文的概括将分为4个不同的时期。在这些时期中,主流的建筑教学方法在宏观的社会文化框架中形成,并体现为一种建筑类型和/或建筑教学体系。这4个框架和时期包括文艺复兴、工业革命、1960年代后期和1990年代后期。在图2的时间线中,概括的情况在时间线的图示上与社会文化环境相对应,每座学校的建筑形象都作了简化和统一。图1以轴测图示的对比表现出各个学校的建筑类型。图5是各所学校简化的建筑类型图示。

3.1 文艺复兴

17世纪,法国政府首次将建筑学列入美术教育,支持学校培养艺术家。在过去,艺术与其他行业共用由社团或行会提供的教育设施,施行在匠师的作坊或家中学徒的制度[8]。“正式的建筑学校创立之后,面对当时的价值体系和政府的需要,出现了唯一的教育模式”[1]。在当时的文艺复兴时期,这种教育模式被称作“巴黎美术学院体系”。奥默·埃金[10]认为,巴黎美术学院出自支持学术机构的政府系统。它成立的目标在于教育,而不是职业培训。科林斯 指出,巴黎美术学院体系与法国的特征和传统相去甚远,在本质上是意大利式的[10]。这是合理的,因为那是源自希腊和罗马帝国的古典主义价值观重生的时代,而将意大利作为建筑教育根源的观点也通过建筑本身出现在当代。巴黎美术学院的建筑学院在一座专门为其设计的建筑中,它被称作“研习宫”。这座建筑是费利克斯·迪邦设计的,以布拉曼特设计的意大利文艺复兴宫殿、罗马文书院宫为原型。这座建筑被设计为陈列展厅,即大门上写的“研习博物馆”。里面展示了建筑模型的铸件、古董的复制品和学生的获奖作品(图3)。在迪邦原来的建筑中,这个展厅在一个露天庭院中[11],后来增加了顶盖,让学生可以在里面观察和临摹这些复制品。巴黎美术学院体系一直是主流的教育模式,而这些建筑表明建筑的价值就在于它们是研习典范的圣殿。世界各地的学校都从这一理念出发,采用了相似的建筑类型——先是在欧洲,19世纪末是在美国。

3.2 工业革命

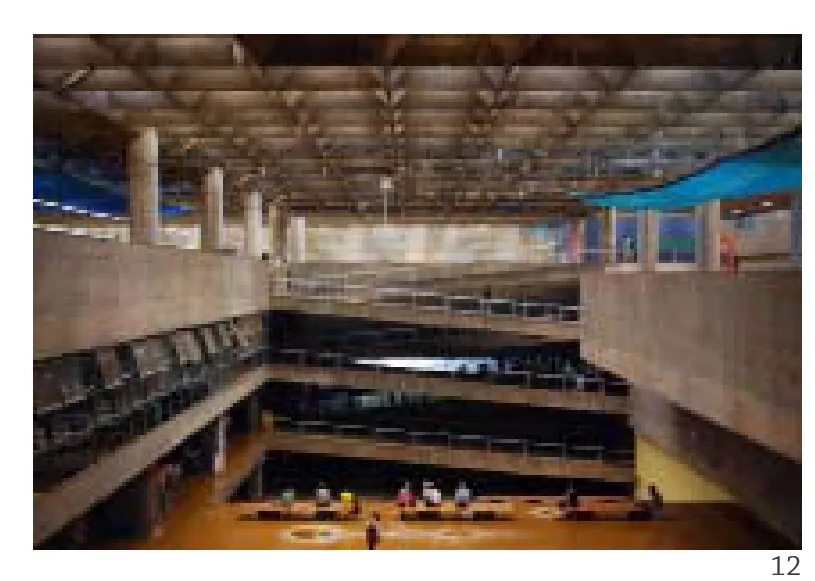

在第一个时期之后,社会文化价值观因工业革命带来的技术进步而改变,建筑教学也随之一变。社会上的所有建筑和工序都采用了标准化的思想,涌现出大量工厂式的空间。新的材料使轻盈、通透、多用的建筑成为可能。这种发展只带来了一种巴黎美术学院之外的体系,并表达出新的价值体系——德国包豪斯[1]。用魏玛包豪斯学校的设计者瓦尔特·格罗皮乌斯的话来说,“新建筑像甩开窗帘一样推倒它的墙壁,让清新的空气和阳光充满房间。它不再用沉重的基础将房屋死死地固定在地上,而是让它们轻轻地、稳稳地立在地面上;它的姿态没有效颦的风格,也没有艳俗的装饰,而是以简洁明快的设计造型,让每一处都自然地融入整体。”[12]但走上这条道路的不只是欧洲,这一时期的很多重要建筑师都在两战期间前往美国,将包豪斯的思想传播到世界的各个角落。比如,密斯·凡·德·罗的芝加哥伊利诺伊理工学院克朗楼就体现出格罗皮乌斯包豪斯通透轻盈的特征。密斯将克朗楼称为“普适空间”,因为这个设计允许建筑改变功能,并且建筑的重点是周边环境的持久。在它落成之际,密斯宣布“它是我们创造的最清晰的建筑,完美地体现了我们的理念”[13](图9)。在南美,在西方现代建筑的巨大影响下,“普适空间”的概念体现在巴西圣保罗建筑与城市学院的设计上。它的建筑师认为,这所学院的设计理念是创造空间连续性。所以,建筑的6层都是通过坡道体系连接起来的,给人一个平面的感受并推崇连续的路线,从而提高了使用者同在一地、相互交流的程度。建筑没有大门、楼梯或小空间,其用意在于创造让人尽情施展的空间 (图12)。

1 Introduction

First of all we should note that it is impossible in a brief article like this one to cover a complete history of the design of architectural education spaces, since this history stretches over several centuries and includes dozens of individual schools and structures with their own development and respective histories. Therefore this article does not attempt to provide such a complete history, but rather confines itself to a brief overview of selected schools and respective typologies of architectural educational, and specifically their spatial characteristics. The design of spaces in which architects are educated is surprisingly not very well studied. There is plenty of research on architectural design education[1-2], and on how to design a curriculum to teach architects[3-4], but for a discipline that has the primary concern "to produce three dimensional spaces and to accommodate related human activities"[1]it is indeed surprising to find very little coherent research regarding in what type of spaces this should happen for it's own discipline. And this lack of academic resources cannot be explained through a lack of available study material for instance, in fact there is a whole series of buildings specifically designed for architectural education in which the architect, together with the institute that it houses, has tried to create a very specific building type for the school's specific ideology regarding architectural education, or vice versa. This paper thus starts with a selection of these individual cases and should be read as an attempt to combine these various efforts into one comparative study1). It is from this overview that this paper then has tried to distill a review of typologies and organization.

2 Methodology

The methodology for this paper follows the initial set up of a comparative case-study analysis, presenting a chronological overview of selected cases of designs of schools of architecture. The case-study method stems from the realm of the social sciences[5], is also widely used in practice-oriented fields such as environmental studies, architecture, and business studies. Case studies can be particularly helpful to refer to the description and analysis of a particular entity[6]and they can provide an in-depth multifaceted investigation[7]. Normally, the purpose of a case-study is to study a complex phenomena by means of making analysis of one or more cases. Hence, the case study is usually seen as "an instance of a broader phenomenon, as part of a larger set of parallel instances"[7]. However, with a detailed investigation of one particular case it can be hard to show how the conclusions of this case can be placed in reference to other cases with similar, or different conditions. It is therefore in the context of this paper, more suitable to provide a multitude of cases within one overall system and to then create a comparative analysis of different responses to the same starting point. Though more cases can thus give a more complete overview, there was a limit to the amount of cases that were able to be picked for the research in this paper, so the author limited the selection of cases to those that in themselves explicitly expressed a teaching ideology in their architecture, or, reversely, cases where the architecture of a particular school informed a particular idea on teaching. In addition, the aim was to select cases from the entire history of individual schools of architecture.

3 A Concise Overview of Typologies

Following Donald Schon[2], who states that society is in a continuing process of transformation, and the learning systems respond to changes associated with this transformation, the review is grouped into four distinct periods, in which a prevailing architectural pedagogy resulted from a broader social-cultural framework that was translated into a type of architecture and/or architectural learning system. We identified four such frameworks and periods: the Renaissance, Industrial Revolution, Post 1960's and Post 1990's. In the accompanying timeline (Fig. 2), this overview is displayed against the social-cultural context in a graphic timeline, with simplified uniform images of each school's building. Fig. 1 shows the various schools' typologies in a diagrammatic axonometric comparison. Fig. 5 displays the simplified typological diagram for the various schools.

3.1 Renaissance

1 建筑学校选例轴测图/Axonometric overview of selected schools of architecture(绘制/Image: 和马町/ Martijn de Geus)

2 建筑教育的建筑类型史总览/Historic overview of typologies of architecture education(绘制/Image: 和马町/Martijn de Geus)

In the seventeenth century, the national government of France undertook for the first time to foster architecture as one of the fine arts by supporting schools for the education of artists. Formerly, the arts had shared with other trades those educational facilities provided by the corporations or guilds under the system of apprenticeships carried on in the workshops or homes of the master craftsmen themselves.[8]"With the establishment of formal architecture schools, there was only one model of education that emerged in response to the value system of the time and the needs of the government[1]. The time was the Renaissance, and the education model was called "Beaux-Arts". According to Omer Akin[9], the Ecole Des Beaux Arts emerged from a system of government which sponsored the academic institutions and was established as an educational program as opposed to a vocational program. Collins points out that the beaux-arts system in France, far from being characteristically and traditionally French, is essentially Italian.[10]This is understandable, as it was the time of rebirth of classical values originating from the Greek and Roman Empire, and this reference to Italy as the source for architectural education was also expressed in more contemporary references through the architecture itself. The school of architecture at the Ecole Des Beaux Arts was housed in a purposefully designed structure called "palais d'etudes". The building was designed by Félix Duban who modelled it after an Italian Renaissance Palace designed by Bramante, the Palazzo della Cancelleria in Rome. The building was designed as a sort of gallery of objects, a Museum of Studies as written above the entrance door, to present castings of architectural patterns, copies of antiques and award-winning works of students (Fig. 3). In the original Duban building, this gallery was in an open courtyard[11], it was covered later, in which students could observe and draw these copies. The Beaux-arts system was long the dominant style of education, and the buildings represented the architectural values clearly as a palace for studying exemplary projects. Various other schools around the world, first in Europe, later around the late 19th century also in the United States, were started with this ideology and followed similar building typologies.

3.2 Industrial Revolution

Following the first period, architectural learning then adapted as social-cultural values changed in response to technological changes stemming from the Industrial Revolution. All structures and processes in society followed ideas of standardisation and factory-like spaces emerged in which new materials enabled light, open and flexible structures. Out of this revolution, only one alternative to the Beaux-Arts developed that embodied the changed value systems, the Bauhaus in Germany[1]. In the words of Walter Gropius, designer of the Bauhaus School in Weimar: "the New Architecture throws open its walls like curtains to admit a plenitude of fresh air, daylight and sunshine. Instead of anchoring buildings ponderously into the ground with massive foundations, it poises them lightly, yet firmly, upon the face of the earth; and bodies itself forth, not in stylistic imitation or ornamental frippery, but in those simple and sharply modelled designs in which every part merges naturally into the comprehensive volume of the whole."[12]Following the particular approach was not only limited to Europe though, as some of the key architects of this period moved to the United States during the times of the two World Wars and brought the modern Bauhaus ideas to the rest of the world. For instance with Mies van der Rohe's Crown Hall for the school of architecture at the Illinois Institute of Technology in Chicago, which followed the open, light and airy characteristics of Gropius' Bauhaus. Mies called the Crown Hall a "universal space", because its design permits change in the function of the building while the architecture focuses on the permanence of the building's surroundings. Upon its opening, Mies van der Rohe declared it "the clearest structure we have done, the best to express our philosophy"[13](Fig. 9). In South America, heavily influenced by the modern Western architecture, the concept of "universal space" was also adhered to in the design of the 'Faculty of Architecture and Urbanism' in Sao Paulo, Brazil. Here the principle design of the school was, according to the architects, based on the idea of generating spatial continuity. Therefore, its six levels are linked by a system of ramps in an attempt to give the feeling of a single plane and favour continuous routes, increasing the degree of coexistence and interaction among those who use it. There are no entrance doors, stairs or small spaces, the intention being the generation of a space in where you can perform any activity that you need to (Fig. 12).

3.3 Post 1960's

The technological advancements stemming from the Industrial Revolution were put to use after the two World Wars following a time of rapid rebuilding and standardisation of building processes. It then took until the (late) 1960's that social values had changed again in such a way as to enforce a radical paradigm shift in architecture, defined by rich diversification based upon further socialcultural experiments, again in line with the spirit of the time. The 1968 destruction of the Pruitt–Igoe urban housing projects designed by Minoru Yamasaki signified a pivotal change in thinking about architecture, away from the anonymous factory, toward more diversified, socially oriented, experimental spatial typologies. This shift was started perhaps with the Yale School of Architecture, designed by Paul Rudolph. Finished in 1963, the architect seems to have anticipated the social-cultural change, since instead of clear, flexible open spaces, the building has quite a complex network of smaller, very particular spaces which are connected in labyrinthine ways (Fig. 16). According to Daga[14]the building turns into a story book, as you pass through varying volumes and spaces of different densities which take on different activities. These create private little pockets and small spaces for different programs. The TU Delft School of Architecture's new building of that time, Bouwkundeiby Broek-Bakema, also purposefully tried to break the all-is-possible-box structure. The architects literally divided the several components of an all-encompassing box up into public elements that could be regrouped along a central street and private study spaces into a slab hovering above the street (Fig. 4). The public elements included the canteen, model shop, drawing studios, etc. and were configured along a central street that resembled an actual outdoor street, with streetlights and informal seating places for exchange and interaction.

3.3 1960 年代后

在一段快速重建和建筑流程标准化的时期之后,工业革命带来的技术成就在两战之后应用开来。到了1960年代(末),社会价值观再次发生变化,迫使建筑的范式彻底转变。其本质是源于社会文化试验发展的多元化,而这又是与时代的精神一致的。1968年,山崎实设计的普鲁伊特-艾戈城市住宅楼被拆除,标志着建筑思想的重大转变:从毫无特征的工厂走向更多元、面向社会的试验空间类型。这种转变或许是从保罗·鲁道夫设计、1963年建成的耶鲁建筑学院开始的。这位建筑师似乎预见到了社会文化的变化,因为这座建筑不是清晰、多用的开放空间,而是以许多特殊的小空间组成的复杂网络,并像迷宫般连接在一起(图16)。达加[14]认为,当人穿过形状不同、疏密有致、活动各异的空间时,建筑就成了一本故事书。这会形成私密的小空间,承载不同的功能。当时的代尔夫特理工大学建筑楼Bouwkundei是Broek-Bakema建筑事务所设计的,他们试图以此打破万能盒子的建筑模式。建筑师将一个通用方盒子的许多部位分成了若干公共空间,再沿中央大街和个人研习空间组合到大街上的板楼中(图4)。这些公共空间包括食堂、模型室、制图工作室等。它们沿着一条中央大街布置,一如真的室外街道,有红绿灯和供人沟通交流的休闲座位。

3 巴黎美术学院研习宫中庭/Beaux Arts Palais d'Etudes Centre Courtyard(图片来源:http://www.grandemasse.org/?c=actu&p=ENSBAENSA_genese_evolution_enseignement_et_lieux_enseignement)

4 代尔夫特理工大学建筑楼概念草图/TU Delft Bouwkunde concept sketch(绘制/Image: Broek-Bakema)

沿公共流线布置各个空间要素的相似手法被弗兰克·劳埃德·赖特用在西塔里埃森建筑学校上,尽管其建筑表达和场地条件带来了一种截然不同的建筑类型。赖特的学校构成犹如一座草原小镇,各种各样的建筑要素创造出丰富多元的内部空间,而与外部空间的紧密联系营造出一种丰富的内外沟通。这样,建筑融入了景观,而不是“固定在地上”(文艺复兴)或者“轻轻地立在地面上”(包豪斯)。阿尔多·凡·艾克的孤儿院也从建筑类型上探讨了建筑与景观的这种关系。它是贝尔拉格建筑学院的所在地,并让室内空间成为一种连续的学习景观2)。

3.4 1990 年代后

在过去的20~30年中,新的建筑学院如雨后春笋出现在世界各地。随着社会价值体系的变化,建筑类型又一次发生了转变。或许可以说1960年代后的大量空间试验形成了两种主要的建筑类型:“混合体”与“盒中盒”。混合体类源于可持续发展的环境意识带来的社会文化转变。其出发点是再利用与再生,而不是新建。这种趋势已经体现在1990年创办的贝尔拉格建筑学院上。这种再利用的思路也为原有建筑增添了元素,使它们适合建筑教育。盒中盒类或许源于快速变化的教育环境,同时技术带来了建造与设计流程的变革,使未来的空间需求难以把握。由此产生的盒中盒类建筑区分了确定和不确定的元素,维续了设计的有效性。

混合体类建筑的例子是2008年代尔夫特理工大学的“BK城”。在上文提到的Broek-Bakema设计的建筑失火倒塌之后,学校决定对大学的一座老建筑进行全面、快速的复兴。出乎意料的是,在对原有建筑的再利用之外,学院要求建筑师团队提出扩建和再利用的方案。建筑教育的特有空间放在新加了顶的庭院中,而原建筑设置了灵活的桌台、办公室和工作室(图8)。

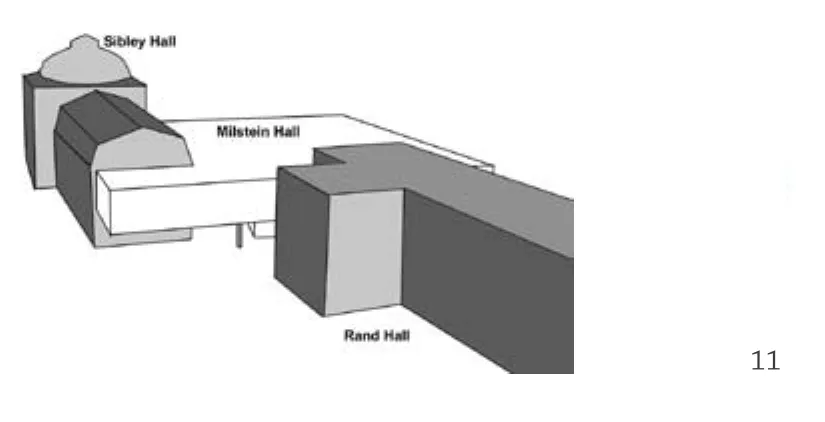

5 建筑类型简化图示/Simplified typological scheme

OMA作的康奈尔大学建筑学院扩建方案采用了相似的模式,用悬浮的方盒子这个新要素重新定义现有的传统建筑类型。新的米尔斯坦连廊悬浮在半空中,将多座老建筑连接起来,并为学院增加了新的空间类型(图10、11)。莫斯科的斯特列尔卡学院采用了一种更为分散的混合体模式,在空间布局上与赖特的“草原小镇概念”相近:用松散的建筑元素创造出像游乐场一样的城市环境,从而为学院和整个城市的环境服务。这样它不仅激活了原有的建筑,更为周边的户外环境注入了生命(图7)。

A similar idea of arranging individual spatial elements along public circulation was used by Frank Lloyd Wright in his Taliesin West School of Architecture, although the architecture expression and site conditions created a very different typology. Wright's school was grouped almost like a small prairie town, in which the various architectural elements created very diversified internal spaces, and the close connection with the outdoor space enabled a rich inside out dynamic. The building thus became part of the landscape, rather than "anchored into the ground" (Renaissance) or "lightly poised upon the earth" (Bauhaus). This relation of building to landscape was also typologically explored by Aldo van Eyck's Orphanage, home of the Berlage Institute, in which the building enables the interior spaces to become a continuous learning landscape2).

3.4 Post 1990's

In the past two to three decades there has been a global increase in the building of new schools of architecture and again a shift in typologies following changing social value systems. Or perhaps we can say that it seems the wide-ranging spatial experiments of the post-1960's have resulted in two dominant typologies; the "patchwork" and the 'box-in-box'. The patchwork type stems from the social-cultural shift following sustainable environmental awareness. The starting point is to re-use and re-generate rather than build new, a trend already expressed by the Berlage Institute in 1990. A part of this re-use strategy is also adding elements to existing buildings that make them suitable for architectural education. The box-in-box type perhaps finds its origin in an increasingly rapidly changing educational environment, with technology leading a change in the process of building and design, in which future spatial requirements are not clear. The resulting "box-inbox" typology splits itself between certain and un-certain elements and thus maintaining efficient planning.

Examples of the Patchwork typology typology included TU Delft's 2008 "BK City", in which the school decided to opt for an extensive, and swiftly executed regeneration of a former university building rather then building a completely new one, following the sudden fire and collapse of the Broek-Bakema designed building mentioned earlier. What is surprising in addition to reusing an existing building, is that the school asked a team of architects to come up with a strategy to add and re-use. Specific architectural education spaces were housed in newly covered courtyards, and the existing structure was to house the more flexible desks, offices and studios. See Fig. 8 for an impression of the model shop, housed in a newly covered former courtyard.

Cornell University's School of Architecture extension by OMA follows a similar model, in which one new element, a floating box, radically redefines the existing traditional typology. The new, floating, Milstein Hall connects several much older structures and at the same time adds new spatial typologies to the school (Fig. 10, 11). The Strelka Institute in Moscow, Russia uses a more scattered patchwork strategy, similar in spatial arrangement to Frank Lloyd Wrights "prairie town idea", in which loosely placed architectural elements create an almost playground like urban environment that serves both the school and the wider urban context. It thus not only regenerates the existing buildings, but becomes a catalyst for the surrounding exterior area as well (Fig. 7).

6 室内空间组织原则总览/Overview of interior organizational principles4)(5.6图片来源/Sources: 和马町/Martijn de Geus)

最后是两个“盒中盒”类建筑的例子。一个是伯纳德·屈米设计的巴黎马尔纳·拉瓦莱学院。建筑师认为,这所学院的设计“前提是存在事件的‘建筑-生成因素’,它会加速或强化发展过程中的已有文化社会变化。”它在空间上转化为一种中心空间,成为在精雕细刻的“方盒子”中承载主要公共功能的社会环境,而周围是在中庭边缘更“私密”的部分。

第二个例子是JWA/NADAAA设计的墨尔本大学设计学院(MSD),它们采用了同样的空间方案。设计包括了中央的工作室大厅,周围是工作室和办公室空间。大厅里悬挂的造型空间之中是会议室。工作室大厅是一个多功用的大空间,“可在一天之中随意使用”[15]。这个设计另一个值得注意的地方是中庭的边缘在公共与个人空间之间创造出了可用的缓冲带(图13)。

4 室内空间组织表达的教学理念

在为建筑教育设计的建筑类型之外,教学方法也在很大程度上依赖室内空间的组织。建筑教育有各种特定的教学空间组成部分,它们可以根据主流的教学理念进行不同的设计和阐释。虽然下文列出的内容并不完整,并且一所学校通常不需要(所有)这些组成部分,但在建筑教育的总体类型设计中,它确实有助于理解某些特定的空间属性。因此,下面从前文提到的学校中选出了3种基本的空间要素实例,进行图像比较(图6)。

4.1 学生的排布

7 斯特列尔卡建筑学院公共论坛/Strelka public forum(图片来 源/Source: 斯特列尔卡设计学院/Strelka)

为了画图,不论是用笔记本电脑、台式机还是草图工具和绘图纸,学生都需要一个平面来工作。最常见的形式是桌子,这乍看起来是设计学校必备的。不过,桌子的类型和布局将在很大程度上影响或体现教学的理念。比如,桌子的大小能否用来画表现图、做建筑模型,还是只能放下一个笔记本电脑;这会决定学生们是否愿意用模型室来开展小组合作,还是待在自己的桌子上。另外,每张桌子是否背对背(如哈佛的冈德楼)、相互独立,还是分组集中(耶鲁);或者采用开放平面的办公室风格(康奈尔,图10),在读期间分配给个人(如哈佛研究生院,图15),每天更换安排(代尔夫特理工大学)还是随意使用(斯特列尔卡),都会影响教学的可能性。它将决定学生是愿意交流还是独自安坐。

4.2 流线

所有的学校都需要组织流线,就像需要桌子一样。而正如桌子能表达理念,流线也会影响各种创意学科的教育空间。特别是学生或小组之间的流线,或者学校公共部分(如讲堂或模型室)与个人工作区之间的流线。以流线作为建筑语汇表达教学体系的途径很多。水平流线可以成为自由交流和会面的场所(如墨尔本大学设计学院,图13)。垂直交通可以设计成相互连通的街道,而不用电梯(如圣保罗的FAU,图12)。或者可以用堆叠元素作为落台,让学生站起身就能看见其他人的工作进展,同时保持自己的私密性(哈佛大学设计研究生院,图15)。

4.3 评图空间

建筑教育特有的是评图空间:学生将作业挂起来,向设计评委展示。针对评图设计的空间一般分为两类:专用评图空间或多用评图空间。在耶鲁,评图空间是多用的,它被称为评图大厅,在楼层中央为双层高。大厅四面敞开,与摆满学生绘图桌的工作室空间相通。在不评图时它也可以用于其他公共活动。工作室空间是围绕这个中央评图空间布置的,并与工作室空间的上部夹层相连(图16剖面)。这些上部空间成了“俯瞰下方的空中楼层,让人们可以聚会也可以独处;分而不离”[14]。不过在塔里埃森,评图空间的位置大不相同,没有端放在注意力的焦点上;而是一个独立的部分,有沙发和躺椅,营造出一种更轻松的展示环境(图14)。

5 结语

本文首先尝试为对比建筑教育的各类空间确定基础,但没有对其设计意图的成功实现作深入的总结,也不对其利用作主观评价。事实上,尽管从前文的概括中不能直接看出,但如果将表1与2017年QS世界前100所建筑学院的排名进行对比就会发现,并不是所有的顶级西方建筑学校(包括MIT、剑桥和苏黎世理工学院)都有专门针对各自教学类型设计的建筑。因此,这种联系对于根据理念提高教育的质量是否必要,是可以讨论的。因为排名第一的建筑学院3)、麻省理工大学就在一座“万神庙风格”的建筑里。从建筑类型的保守性来看,这与前瞻性的教学理念是背道而驰的。不过,排名前10的西方学校大多数都有表达其教学理念或与之相适应的建筑,包括代尔夫特理工大学、哈佛研究生院、加州大学伯克利分校和巴特莱特建筑学院。第二,对于有专门为其教学类型设计建筑的学校,似乎在学校的教学方法与教育空间的设计和使用之间的确存在一种密切的联系。第三,在总体类型中有各种各样的室内组织特征,在建筑类型之外表达出学校教学特色。第四,我们可以从历史概括中看到特定的基本类型。其中有两种是当代的主流之选:“盒中盒”与可持续的“混合体”再生策略。

8 代尔夫特理工“BK城”模型室/TU Delft "BK City" model shop

9 伊利诺伊理工学院克朗楼工作室内部/ITT Crown Hall studio interior(图片来源/Source: Becca Waterloo: https://bwaterloo.wordpress.com/)

最后,张利教授在关于设计教学空间教学方法的文章中指出,设计教学的空间对建立我们的建筑价值观有举足轻重的影响[16]。本文希望证明建筑教育空间的设计能够并且已经表达出了一种思想或与建筑教育有关的价值观。所以,如果说建筑教育的空间在历史上体现出了社会文化的时代精神及其在特定空间类型上的表达,那么我们作为建筑师和教育家就应该扪心自问:最适合表达当代时代精神及其建筑教育观点的空间是什么?在将这个问题作为建筑师品味或理念的个人表达之外,或许本文可以作为在建筑教育空间类型演变的宏观过程中探讨这一问题的一个起点。□

Lastly, two examples of the 'box-in'box typology. Firstly, the Marne La Vallee school in Paris, France by Bernard Tschumi. According to the architect, the design of the school "begins from the thesis that there are 'buildinggenerators' of events which (…) accelerate or intensify a cultural and social transformation that is already in progress." Spatially this translates to a central space as a social environment that houses the main public programs in sculpted "boxes", surrounded by more "private" components around the atrium's edge.

The second example, Melbourne University's School of Design (MSD), designed by JWA/ NADAA, follows this same spatial strategy. The design comprises of a central Studio Hall, surrounded by studio and office spaces, with meeting rooms inside a sculptural volume floating in the hall. The Studio Hall itself is a large flexible space that "provides for informal occupation over all times of the day"[15]. Notable in this design is also how the edge of the atrium provides an inhabitable buffer between the public and the private spaces (Fig. 13).

4 Teaching Ideology Expressed Through Interior Organization

In addition to the architectural typology of the buildings designed for architectural education, the teaching pedagogy is also heavily relying on the interior organization. There are various specific didactic spatial components for architectural education, and these can be designed and interpreted differently according to a prevailing teaching ideology. Although the following list is not complete, and a school arguably does not need (all of) the listed components below, it does help us understand some specific spatial characteristics considered within the overall typological design for architectural education. Thus below are three basic examples of spatial elements picked from the before-mentioned schools, they are also graphically put together for comparison in Fig. 6.

4.1 Student Arrangement

In order to draw, whether it's on a laptop, fixed computer or sketch roll and paper, a student needs a flat surfaces to work on. This is most often in the form of a desk, which initially seems an arbitrary element in the design of schools, however, the type of desk and its arrangement can heavily influence or communicate the educational ideology. For instance, whether the size of a desk allows for drawing presentation drawings, or building models, or only has room for a laptop determines whether students are encouraged to use a model shop for group work, or instead remain fixed to their own desks. Or whether the desks are individually placed back to back (eg. Harvard's Gund Hall, Fig. 15), separated, or grouped together in small groups (Yale) or in an open plan office style (Cornell, Fig. 10), or perhaps assigned to a person throughout for the duration of the program (Harvard GSD), or flexibly defined on a day to day basis (TU Delft), or informally occupied (Strelka) all influence the teaching possibilities. It determines whether a student is encouraged to interact, or to stay put.

4.2 Circulation

All schools also need circulation, like they all need desks. In the same way that a desk communicates a philosophy, so does the circulation influence spaces for education of creative disciplines. In particular the circulation between one student, or groups of students. Or the circulation between public parts of the school, like lecture halls or model shops, and private working areas. There are various way the learning system can be expressed in the way the circulation is part of the architectural expression. Perhaps the horizontal circulation becomes a place for informal exchange and meetings (like at the Melbourne School of Design, Fig. 13), or the vertical circulation is designed as a connecting, continuous street instead of using elevators (like at Sao Paulo's FAU, Fig. 12). Or, you can use the stacking of elements as a stepped terrace so that students can look out onto each other's work in progress if they stand up, while still maintaining their individual privacy (Harvard GSD, Fig. 15).

4.3 Critic Space

Very specific for architectural education are the critic or review spaces, in which students pin up and present their works in front of a design jury. Designs for these reviews broadly fall into two categories; designated review space, or flexible review spaces. In Yale, the crit space is a flexible space conceived as a double height volume in the centre of the floor, called the review hall. It is open from all sides and pours out in the studio spaces with student desks, which can be used for other public activities when there are no reviews taking place. The studio spaces are actually arranged around this central review space and are connected to the upper mezzanine of studio spaces, clearly represented in the section in Fig. 16. These upper spaces become "overlooking, floating slabs which give an opportunity to be together, yet separate; involved yet detached"[14]. In Taliesin however, the review space is very differently situated, not very formal in the centre of the attention, but in a separated section, with sofas and lounge chairs that allow for a more informal presentation environment (Fig. 14).

5 Conclusion

This article has tried foremost to find a base to compare the several types of spaces for architectural education, and should not be seen as an in-depth conclusion about the success of their intentions, or a subjective valuation of their appropriation. In fact, though not directly clear from the previous overview, if we compare attached Table 1 to the 2017 QS raking of top hundred schools of architecture in the world, not all the top-ranked Western architectural schools (including MIT, Cambridge or ETH Zurich) have buildings designed specifically for their respective teaching typology. Whether such a link is necessary to foster the quality of education in line with the ideology is thus debatable, as the school of architecture ranked 1st in the ranks , the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, is housed in a "Pantheon style" building which in its typological conservatism couldn't be more opposite with their forward oriented teaching philosophy. However, of the top ten ranked western schools, most of them have buildings that express, or are made to fit for their teaching ideology, including TU Delft, Harvard GSD, UC Berkeley, Bartlett. Secondly, for the ones that do have buildings designed specifically for their respective teaching typology, there indeed seems to be a strong connection to the pedagogy of the school and the use and design of the educational spaces. Thirdly, within the over-arching typology there is a palette of interior organizational characteristics that in addition to the typology of the architecture express the teaching character of the school. Fourthly, we can identify specific base typologies in the historic overview, of which two seem to be the most dominant contemporary choices: the "box in box" and the sustainable "patchwork" regeneration strategy.

11 新的米尔斯坦楼与两座原有建筑的组合方式/How the new Milstein Hall is integrating two existing structures(图片来源/Source: OMA www.oma.eu)

10 康奈尔大学米尔斯坦楼室内鸟瞰/Aerial interior photograph of Milstein Hall, Cornell University (图片来源/Source: Brett Beyer: http://brettbeyerphotography.com/)

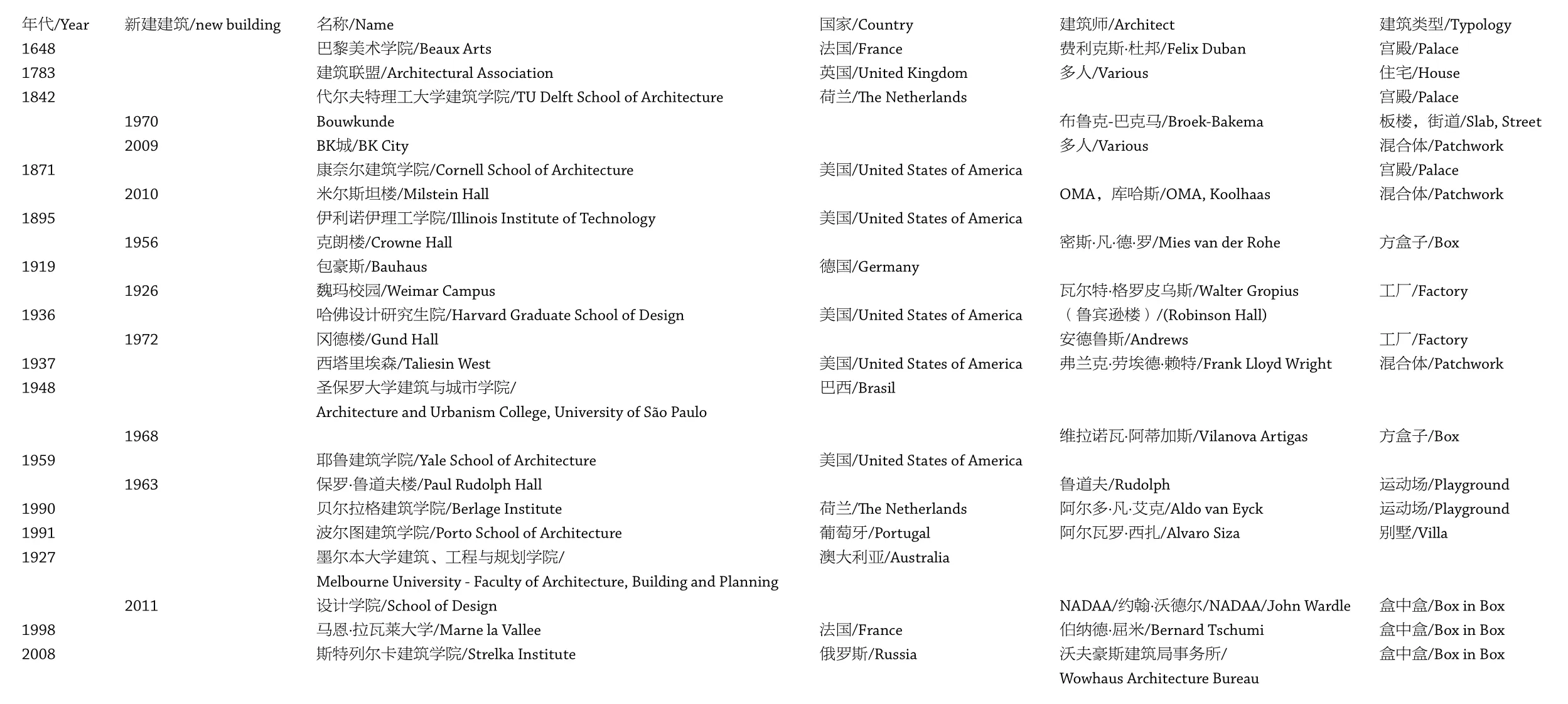

表1 选例年表 /Table 1 Historic Overview of Selected Cases

12 圣保罗大学建筑与城市学院:没有大门、楼梯或小空间,各层由坡道相连/Architecture and Urbanism College, University of São Paulo, there are no entrance doors, stairs or small spaces, with ramps connecting the floors(图片来源/Source: flickr FADB. 授权许可creative commons)

13 墨尔本设计学院剖透视/Perspective section of Melbourne School of Design (图片来源/Source: http://www.archdaily. com/622708/melbourne-school-of-design-university-of- melbourne-john-wardle-architects-nadaaa)

14 塔里埃森建筑学校“起居室式”评图空间/Taliesin School of Architecture, "living room like" crit space (图片来源/Source: www.inhabitat.com)

15 哈佛研究生院带个人用桌的平台/The trays with private desks at Harvard GSD(图片来源/Source: www.gsd.harvard.edu/)

编注/Editor's Note

i 荷兰语"Bouwkunde"译为建筑,缩写为BK/Word "Bouwkunde"(Dutch) means architecture, abbreviated as BK.

注释/Notes

1)本研究出自作者参加的代尔夫特新建筑学院设计竞赛。竞赛的起因是2008年Broek-Bakema建筑事务所设计的建筑失火倒塌。建筑师很少有机会能对与自身实践发展紧密相关的当代建筑类型进行彻底的反思。当时作者的团队全力以赴,首先对建筑教育设计的主流观点进行了概括。见参考文献[24] /The original base for this research came about when the author entered the design competition for Delft University's new school of architecture, following the 2008 fire that let to the collapse of the Broek-Bakema designed building. Not often are architects confronted with an opportunity to radically rethink a contemporary typology so relevant to the progress of their own practice. Our team just then took a serious stance to first of all create an overview of what the prevailing view on design for architectural education. See: Reference [24].

2)贝尔拉格建筑学院在这个综述中略有奇怪,因为它所在的建筑并非专门为这个学院而设计,建筑学院是在1990年成立时搬到这里的。不过,贝尔拉格建筑学院的创始人赫尔曼·赫茨贝格与原建筑的设计师阿尔多·凡·艾克之间的关系在理念上是有所重叠的。赫茨贝格利用这种建筑类型作为实现某种建筑教育的工具。所以在这里加以阐述。/The Berlage is a slightly odd school in this overview, since it was not housed in a building specifically designed for the school, but only moved there in 1990, when it was founded. However, the relation between the founder of the Berlage, Herman Hertzberger and Aldo

Lastly, in his article on the pedagogic aspect of design teaching spaces[16], ZHANG states that spaces for design teaching have fundamental impacts in the setting up of our values towards architecture. With this paper, the author hopes to have shown that indeed the design of spaces for architectural education can and has been a translation of an idea, or values regarding architectural education. Thus if the spaces of architectural education have historically embodied the social-cultural Zeitgeist and its expression in a particular spatial typology, we as architects and educators should ask ourselves the question of what should be the most appropriate space for expressing the contemporary Zeitgeist and its views on architectural education? And rather than this question being an expression of an individual architect's taste or ideology, perhaps this paper can be a starting point to explore this question within a broader context of the typological evolution of spaces for architectural education.□van Eyck, designer of the original structure, is one of overlapping ideologies. And Hertzberger utilised the architecture typology as a tool to enable a certain type of architectural education. It is thus included here.

3)The QS ranking can be found online at: https://www.topuniversities.com/university-rankings/university-subject-rankings/2016/architecture

4)感谢西蒙·亨斯特拉协助绘制了图1、4、5和6/Thanks to Simon Henstra in assisting in making the diagrams 1, 4, 5 and 6.

16 耶鲁建筑学院鲁道夫楼。剖面显示出中央评图空间,周围是工作室/Yale School of Architecture, Rudolph Hall. Section shows central crit space, with studios situated around it(图片来源:参考文献[17])

/References

[1] Salama, Ashraf. New trends in architectural education: Designing the design studio. Arti-arch, 1995.[2] Schon, Donald A. Beyond the stable state: Public and private learning in a changing society. Maurice Temple Smith Ltd. 1971.

[3] Hertzberger, Herman. Lessons for Students in Architecture. 010 Publishers, 2001.

[4] Alexander, Christopher (1977). A Pattern Language: Towns, Buildings, Construction. Oxford University Press.[5] Johansson, R. Case study methodology. Methodologies in Housing Research, Stockholm, 2003. [6] Bromley, D. B. (1986). The case-study method in psychology and related-disciplines. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons.

[7] Feigin, J. R., Orum, A. M., & Sjoberg, G. (1991). A case for case study. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press.

[8] Cret, Paul P. The Ecole Des Beaux-Arts and Architectural Education. Journal of the American Society of Architectural Historians 1, no. 2 (1941): 3-15.

[9] Akin, Omer. "Role models in architectural education," in The Role of the Architect in Society, ed. by P. Burgess, Pittsburgh: Carnegie Mellon University, Department of Architecture, 1983: 9-13.

[10] Collins. Architectural Criteria & French Traditions. 1966.

[11] https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Palais_des_Études

[12] Gropius, Walter. The New Architecture and the Bauhaus. MIT Press, 1965.

[13] Thompson, Eric D. National Historic Landmark Nomination: S.R. Crown Hall, National Park Service. 2000.

[14] Daga, Anuj. The Paul Rudolph Hall. 2012./https://yalestories.wordpress.com/2012/08/31/the-paulrudolph-hall/

[15] JWA/ NADAA. Melbourne School of Design University of Melbourne. Archdaily. 2015. Accessed via: http://www.archdaily.com/622708/melbourneschool-of-design-university-of-melbourne-johnwardle-architects-nadaaa

[16] Zhang, Li. Pedagogical Positions of Design Teaching Spaces. World Architecture. 2017. July Issue: 8-9.

[17] Lewis, Paul, Tsurumaki, Marc and Lewis, David J. The Manual of Section. Princeton Architectural Press. 2008.

[18] Van der Voordt, Theo & Zijlstra, Hielkje & Dobbelsteen, Andy & Dorst, M. Integrale plananalyse van gebouwen. Doel, methoden en analysekader. 2007.

[19] Weismehl, Leonard A. Changes in French Architectural Education. Journal of Architectural Education Vol. 21 , Iss. 3, 1967.

[20] Foster, James. T. Moscow's Strelka Institute and the HSE Graduate School of Urbanism Launch a New Course in Advanced Urban Design. 2016. [18] http://www.archdaily.com/783143/moscows-strelkainstitute-and-the-hse-graduate-school-of-urbanismcreate-a-new-course-in-advanced-urban-design

[21] Cour vitrée du Palais des Études où se situait le Musée des Antiques - 1937 Photographie de Georges GliDFARB (Atelier libre d'Architecture EXPERT). Accessed via: http://www.grandemasse.org/?c=actu&p=ENSBA-ENSA_genese_evolution_enseignement_et_lieux_enseignementhttps://www.beauxartsparis.fr/fr/locations-d-espaces

[22] http://www.tschumi.com/projects/15/#

[23]https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Berlage_Institute https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Architectural_Association_School_of_Architecture

[24] Koehler, Marc and De Geus, Martijn. Ego-Eco System. 2008. Accessed via: https://www.archined.nl/2009/03/building-for-bouwkunde-the-nomineesthe-winners

[25] https://arch.iit.edu/about/history

[26] http://www.eekhoutbouw.nl/expertise/bedrijfsruimten/tu-delft-bouwkunde-delft/

[27] https://aap.cornell.edu/about/campusesfacilities/ithaca/milstein-hall/studio-overhead

Review of Spaces for Architectural Education in Western Universities: Typologies and Interior Organization

Martijn de Geus

Translated by SHANG Jin

This paper combines an overview of the development of spaces for architectural education in Western universities in which a certain idea on teaching architecture is explicitly expressed in the design typology of the school's architecture and its interior organization. This paper will therefore work in two parts. First of all a review of the typological evolution, as a history of the design of schools of architecture in the Western world. This will be done by presenting a chronological overview of selected typologies of schools that explicitly express(ed) teaching ideology in their architecture, or, reversely, cases where the architecture of a particular school informed an idea on teaching. The paper's starting point follows Donald Schon's theory, who states that society is in a continuing process of transformation, and that learning systems respond to changes associated with this transformation. The presented review of spaces for architectural education in western universities shows that the evolution of learning systems are the result of subsequent architectural ideologies and didactic principles in which new dogma's replace old ones. Secondly, after the macro overview, we will briefly consider specific interior elements that particularly express a spatial idea on didactics or pedagogy, and again present a selection of examples for comparison.Lastly, after this overview in two parts, a brief conclusion reflects on what we can distill from these two overviews.

architectural design spaces, architecture education, education design, typologies, studio design, review space

清华大学建筑学院

2017-07-27