西双版纳热带季雨林木质藤本多样性及其攀援方式*

刘 奇 吴怀栋 谭运洪 张教林

(1. 中国科学院西双版纳热带植物园 勐腊 666303; 2.中国科学院大学 北京 100049)

西双版纳热带季雨林木质藤本多样性及其攀援方式*

刘 奇1,2吴怀栋1,2谭运洪1张教林1

(1. 中国科学院西双版纳热带植物园 勐腊 666303; 2.中国科学院大学 北京 100049)

【目的】 揭示西双版纳地区热带季雨林内木质藤本多样性特征,阐明木质藤本对热带季雨林共存树木的攀援方式,为研究木质藤本对热带森林更新、动态和碳固定等生态过程的影响奠定基础。【方法】 参考巴拿马热带季雨林木质藤本普查规范,调查并鉴定西双版纳热带季雨林20 hm2动态监测大样地中500块20 m × 20 m样地中胸径≥ 1 cm的木质藤本,分析其空间分布、多样性、丰富度、径级、攀援方式及其对共生树木的攀援状况。【结果】 20 hm2大样地中胸径≥1 cm的木质藤本共有21 781株(包括分株),密度为1 089.1 株·hm-2,其中20 611株鉴定到种,分属127种45个科; 样地中木质藤本的优势科为豆科和葡萄科,分别占木质藤本物种总数的51.1%和24.4%; 夹竹桃科的长节珠个体最多(2 382株),占木质藤本总株数的10.9%,其次为梧桐科的全缘刺果藤和番荔枝科的黑风藤,分别占木质藤本个体总数的10.3%和4.6%; 重要值排名前三的木质藤本分别为全缘刺果藤、长节珠和阔叶风车子; 样地中共有43个稀有种(密度≤1株·hm-2),占总种数的33.6%,但个体数仅占个体总数的1.4%; 小径级木质藤本在样地中比例较高,胸径1~5 cm的个体数占总个体数的86.6%,胸径≥10 cm的仅占总个体数的0.7%; 茎缠绕是主要攀援方式,所占比例达58.0%,其次是钩刺攀援和卷须缠绕,分别占16.0%和15.0%; 依靠叶卷须、花梗进行攀援或蔓生的木质藤本比例较小,各占1.0%; 约10.7%的树木个体(胸径≥1 cm)被木质藤本攀援,被攀援树木种数占总树种数的68.2%; 随着树木个体增大,其上攀援的木质藤本数量逐渐降低,但树木被木质藤本攀援的比例增加。【结论】 西双版纳热带季雨林内木质藤本种类丰富,样地中出现豆科木质藤本葛藤等先锋木质藤本表明该热带季雨林历史上可能遭受较严重干扰,加之该地区降雨季节性比较明显,使得西双版纳热带季雨林维持了较高的木质藤本多样性。

多样性; 木质藤本; 攀援方式; 西双版纳热带季雨林; 20 hm2动态监测大样地

Abstract: 【Objective】 Lianas are important components of tropical seasonal rainforest. Theobjective of this study are to investigate the liana diversity, to elucidate the climbing situation of lianas on co-occurring trees, and to better understand how lianas influence the regeneration, dynamics, and carbon sequestration of tropical seasonal rainforest in Xishuangbanna, Yunnan Province.【Method】 Following the liana census protocol applied in Panamanian rainforest, we surveyed and identified all rooted lianas with diameter at breast height (DBH) ≥ 1 cm in 500 quadrats (20 m ×20 m) in a 20 hm2tropical rainforest dynamics big plot which was established in 2007. We analyzed the liana spatial distribution, diversity, abundance, size, climbing mechanisms and situations on co-occurring trees.【Result】 In the 20 hm2plot, 21 781 rooted liana individuals were recorded, with density of 1 089.1 individuals·hm-2. 20 611 individuals from 127 species in 45 families were identified. The two most abundant families wereFabaceaeandVitaceae, accounting for 51.1% of and 24.4% of liana species, respectively. The most abundant lianas wereParamerialaevigata(Apocynaceae) with 2 382 individuals in the plot, constituting 10.9% of all liana individuals.Byttneriaintegrifolia(Sterculiaceae) andFissistigmapolyanthum(Annonaceae) accounted for 10.3% and 4.6%. The top three liana species with the highest important values wereByttneriaintegrifolia,ParamerialaevigataandCombretumlatifolium(Combretaceae). Forty-three rare species with density ≤ 1 individual·hm-2were recorded, accounting for 33.6% of the total number of liana species, but only 1.4% of the liana individuals in the plot. Lianas with 1-5 cm DBH were dominant, constituting 86.6% of all liana individual, whereas lianas with DBH ≥ 10 cm only accounted for 0.7%. 58.0% of liana species employed stem twining to climb the forest canopy, followed by leaf-tendril climbers, sprawlers, and hook climbers, with each accounting for 1.0% of liana species. About 10.7% of the all co-occurring tree individuals (DBH ≥ 1 cm) were climbed by lianas, with 68.2% of the tree species being climbed. With an increase in tree size, the numbers of lianas climbing trees decreased, but the percentage of trees climbed by lianas was increased.【Conclusion】 Lianas are abundant in Xishuangbanna tropical seasonal rainforest. The pioneer lianas, such asPuerariamontana(a legume liana), occur in the permanent plot, indicating that this plot was probably intensely disturbed in history. Disturbance, along with the distinct rainfall seasonality, could be the major factors shaping abundant lianas in Xishuangbanna tropical seasonal rainforest.

Keywords: diversity; lianas; climber mechanisms; Xishuangbanna; 20 hm2tropical seasonal rainforest dynamics big plot

木质藤本是一类不能直立、具有明显攀援习性的结构寄生植物类群。木质藤本主要分布在热带地区,尤其在热带雨林中丰富度和多样性最高(Schnitzeretal., 2002; 2011; Schnitzer, 2005)。研究表明,美洲热带雨林中约25%的木本植物种类、40%的植物个体为木质藤本(Gerwingetal., 2000; Chaveetal., 2001)。在亚马逊地区,木质藤本贡献了地上生物量的5%~15%(Putz, 1983)。木质藤本在受干扰的生境如次生林、砍伐迹地、林缘和林窗中具有更高的丰富度(DeWaltetal., 2000; Lauranceetal., 1998),在某些干扰严重的地区木质藤本对生物量的贡献可达30%(Schnitzeretal., 2011)。随着全球气候变化加剧,木质藤本丰富度呈增加趋势,势必影响共存树木的生长、死亡、多样性和碳固定,进而影响整个森林更新的速度、方向和结果(Ichihashietal., 2015; van der Heijdenetal.,2015; Wrightetal., 2015)。

植物多样性与生境因子密切相关,受降雨量及其季节分配模式、土壤类型、地形条件及干扰状况等影响(Schnitzeretal., 2002)。研究表明,木质藤本的多度与年平均降水量呈负相关,与降水的季节性呈正相关(Schnitzer, 2005; DeWaltetal., 2010)。地形对木质藤本的多度与分布具有重要影响,如在日本冲绳的次生绿林中,木质藤本更趋向于分布在土壤水分、养分富集的生境中,而这种生境主要受地形的影响(Kusumotoetal., 2008)。

木质藤本对森林的结构、动态与功能等生态过程有重要影响(陈亚军等, 2008):在地上,木质藤本可以通过攀援到达林冠,与宿主树木竞争光资源;在地下,与共存树木竞争水分和养分。

目前,全球利用固定样地对木质藤本多样性进行研究主要集中在66个样地(http:∥www.lianaecologyproject.com),其中19个样地分布在热带美洲。在这些样地中,约65%的样地面积小于1 hm2,面积≥20 hm2的样地全球仅有4个,包括巴拿马BCI的50 hm2样地、智利Bosque Experimental San Martin的40 hm2样地、喀麦隆Ebom的33 hm2样地和印度Varagalaiar的30 hm2样地。与热带美洲相比,东南亚的木质藤本普查样地数量最少,仅在马来西亚和泰国调查<10 hm2的样地。中国森林生物多样性监测网络(http:∥www.cfbiodiv.org/yjcg.asp)固定样地中木质藤本多样性研究至今未见报道。

中国种子植物区系中木质藤本种类丰富,共有76科2 175个种(胡亮等, 2010)。西双版纳木质藤本种类非常丰富(朱华, 2011),但对木质藤本多样性进行研究的报道仍不多。深入研究这一地区木质藤本多样性及其对树木的攀援情况有助于全面了解和认识热带雨林的功能和健康。

本研究依托西双版纳20 hm2热带季雨林动态监测大样地,调查大样地中胸径≥1 cm木质藤本及其对树木的攀援情况,以期掌握西双版纳热带季雨林木质藤本的丰富度和多样性特征及木质藤本攀援方式。

1 研究区概况

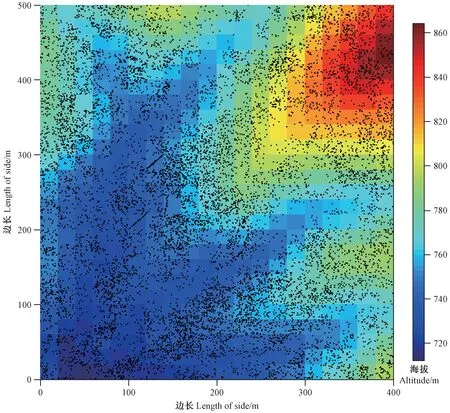

研究区位于西双版纳州勐腊县补蚌村南贡山东部的斑马山山脚(101°34′26″—101°34′47″E,21°36′42″—21°36′58″N)。西双版纳热带季雨林20 hm2动态监测大样地由中国科学院西双版纳热带植物园和西双版纳州自然保护区管理局参照美国热带森林研究中心的样地技术规范于2007年建成,是中国森林生物多样性动态研究网络的重要成员之一。大样地东西长500 m,南北长400 m,划分成500块20 m × 20 m样地。大样地最高海拔869 m,最低海拔709 m,样地地形变化比较大,有3条溪流流经样地。研究区平均气温21.5 ℃,≥10 ℃年积温7 860 ℃,相对空气湿度86%,年均降水量1 400 mm,约85%的降水量集中在雨季(5—10月),有长达6个月的旱季(11月至翌年4月),降水的季节性强(何云玲等, 2007)。土壤类型为砖红壤,有机质含量为18.4 g· kg-1,全氮含量为1.83 g· kg-1,有效氮含量为180 mg ·kg-1,全磷含量为0.34 g ·kg-1,全钾含量为11.2 g· kg-1(Huetal., 2012)。大样地主要植被类型为以热带雨林标志性树种龙脑香科(Dipterocarpaceae)的望天树(Parashoreachinensis)占优势的热带季雨林,共有胸径≥1 cm的树木95 834株,468种,隶属于70个科、213个属(兰国玉等, 2008)。

2 研究方法

2.1木质藤本调查

研究始于2013年旱季,至2014年雨季完成大样地内胸径≥1 cm的所有木质藤本普查工作,普查方法参考Schnitzer等(2006; 2008; 2010)建立的木质藤本普查规范。对20 hm2大样地内500块20 m × 20 m样地中胸径≥1 cm的所有木质藤本个体进行测量、挂牌、定位,在测量部位涂上油漆,以备将来复查。由于木质藤本具有较强的克隆生长能力,根的分株能独立生长,因此凡是具有独立根点的木质藤本均视为不同个体。在调查本质藤本时,记录每个木质藤本的胸径、根位置、攀援方式和宿主树木的种类及个体大小。

所有个体均鉴定到种,共采集实物标本200余份,存放于中国科学院西双版纳热带植物园标本馆。经典植物分类主要依靠植物的花、果、叶进行鉴定。由于木质藤本常攀援到林冠,很难采集到叶片、花、果实的标本,因此主要利用木质藤本茎的特征进行分类鉴定,包括茎的形状、皮孔、木栓、瘤凸、钩刺、纹理、气味等容易识别的少数几个关键特征。尽管如此,仍有部分个体无法鉴定,鉴定率约为95%,与国际上同类研究的鉴定率相当或略高。

参照Darwin(1865)、Putz(1984)和Schnitzer等(2002)的方法,将木质藤本攀援方式分为根附、茎缠绕、枝缠绕、叶卷须、茎卷须、钩刺、花梗和蔓生8个类别。木质藤本常同时具有多种攀援方式,本研究只分析每种藤本最重要的攀援方式。

2.2数据处理

研究采用Shannon-Wiener指数、Pielou均匀度指数(Magurran, 1988)计算木质藤本多样性:

式中:H为Shannon-Wiener指数;S为物种总数;pi为种i的个体数占个体总数的比例;E为Pielou均匀度指数。

木质藤本的重要值计算公式(Greig-Smith, 1983)为:

IV=RF + RA + RD。

式中: IV为重要值; RF为相对频度,指某种木质藤本频度占全部木质藤本频度总和的百分比; RA为相对优势度,指某种木质藤本个体胸高断面积之和占样地全部木质藤本个体胸高断面积总和的百分比; RD为相对密度,指某种木质藤本的密度占全部木质藤本的密度百分比。

用卡方检验分析不同树种间(DBH ≥10 cm、株数大于30)被木质藤本攀援比例的差异。

所有统计分析在SPSS和Excel软件中完成,分布图在R软件(vegan包)中完成。

3 结果与分析

3.1木质藤本多样性

大样地内共有胸径≥1 cm的木质藤本21 781株(包括分株)(图1)。其中20 611株已鉴定到种,共127种45科85属,未鉴定1 170株,占木质藤本个体总数的5.4%。个体数最多的木质藤本是夹竹桃科(Apocynaceae)的长节珠(Paramerialaevigata),共有个体2 382个,占藤本总个数的10.9%,其次为梧桐科(Sterculiaceae)的全缘刺果藤(Byttneriaintegrifolia)和番荔枝科(Annonaceae)的黑风藤(Fissistigmapolyanthum),分别占藤本个体总数的10.3%和4.6%。豆科(Fabaceae)木质藤本最多,共有23种,其次为葡萄科(Vitaceae),共有11个种,分别占总物种数的51.1%和24.4%。

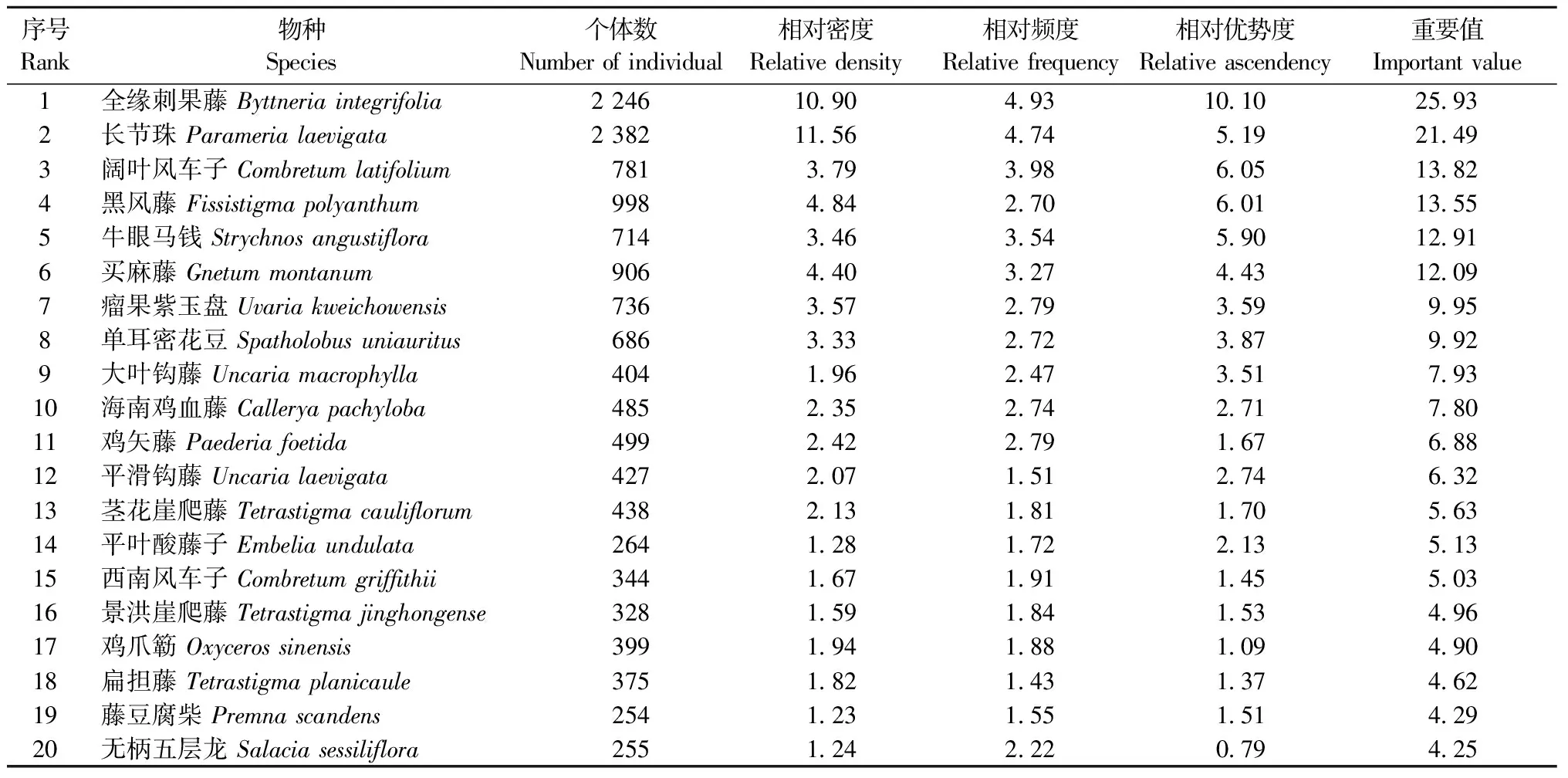

木质藤本的Shannon-Wiener指数为3.8,Pielou均匀度指数为0.8。全缘刺果藤的重要值最大,长节珠在个体数量上虽然多于全缘刺果藤,但因径级小,其重要值排名第二,阔叶风车子(Combretumlatifolium)的重要值排名第三(表1)。Hubbell等(1986)把每公顷个体数少于1的种定义为稀有种。根据此定义,西双版纳20 hm2动态监测大样地内木质藤本共有43个稀有种,占木质藤本总种数的33.6%,稀有种占到样地内木质藤本物种总数的近1/3,但却只占个体总数的1.4%。

图1 西双版纳热带季雨林20 hm2动态监测大样地木质藤本空间分布Fig.1 Spatial distribution of lianas in Xishuangbanna 20 hm2 tropical seasonal rainforest dynamics big plot

序号Rank物种Species个体数Numberofindividual相对密度Relativedensity相对频度Relativefrequency相对优势度Relativeascendency重要值Importantvalue1全缘刺果藤Byttneriaintegrifolia224610 904 9310 1025 932长节珠Paramerialaevigata238211 564 745 1921 493阔叶风车子Combretumlatifolium7813 793 986 0513 824黑风藤Fissistigmapolyanthum9984 842 706 0113 555牛眼马钱Strychnosangustiflora7143 463 545 9012 916买麻藤Gnetummontanum9064 403 274 4312 097瘤果紫玉盘Uvariakweichowensis7363 572 793 599 958单耳密花豆Spatholobusuniauritus6863 332 723 879 929大叶钩藤Uncariamacrophylla4041 962 473 517 9310海南鸡血藤Calleryapachyloba4852 352 742 717 8011鸡矢藤Paederiafoetida4992 422 791 676 8812平滑钩藤Uncarialaevigata4272 071 512 746 3213茎花崖爬藤Tetrastigmacauliflorum4382 131 811 705 6314平叶酸藤子Embeliaundulata2641 281 722 135 1315西南风车子Combretumgriffithii3441 671 911 455 0316景洪崖爬藤Tetrastigmajinghongense3281 591 841 534 9617鸡爪簕Oxycerossinensis3991 941 881 094 9018扁担藤Tetrastigmaplanicaule3751 821 431 374 6219藤豆腐柴Premnascandens2541 231 551 514 2920无柄五层龙Salaciasessiliflora2551 242 220 794 25

3.2径级分布

根据胸径大小将木质藤本划分为4个径级(1~2, 2~5, 5~10和≥10 cm)。随着胸径增加,木质藤本数量显著降低(图2)。大样地中小径级的木质藤本较多,1~5 cm的木质藤本个体数占总个体数的86.6%。胸径≥10 cm的木质藤本仅为151株,占总个体数的0.7%。大样地中个体最大的木质藤本为圆叶羊蹄甲(Bauhiniawallichii),胸径达24.5 cm。

图2 西双版纳热带季雨林森林动态监测大样地木 质藤本径级分布Fig.2 DBH class of lianas in Xishuangbanna 20 hm2 tropical seasonal rainforest dynamics big plot

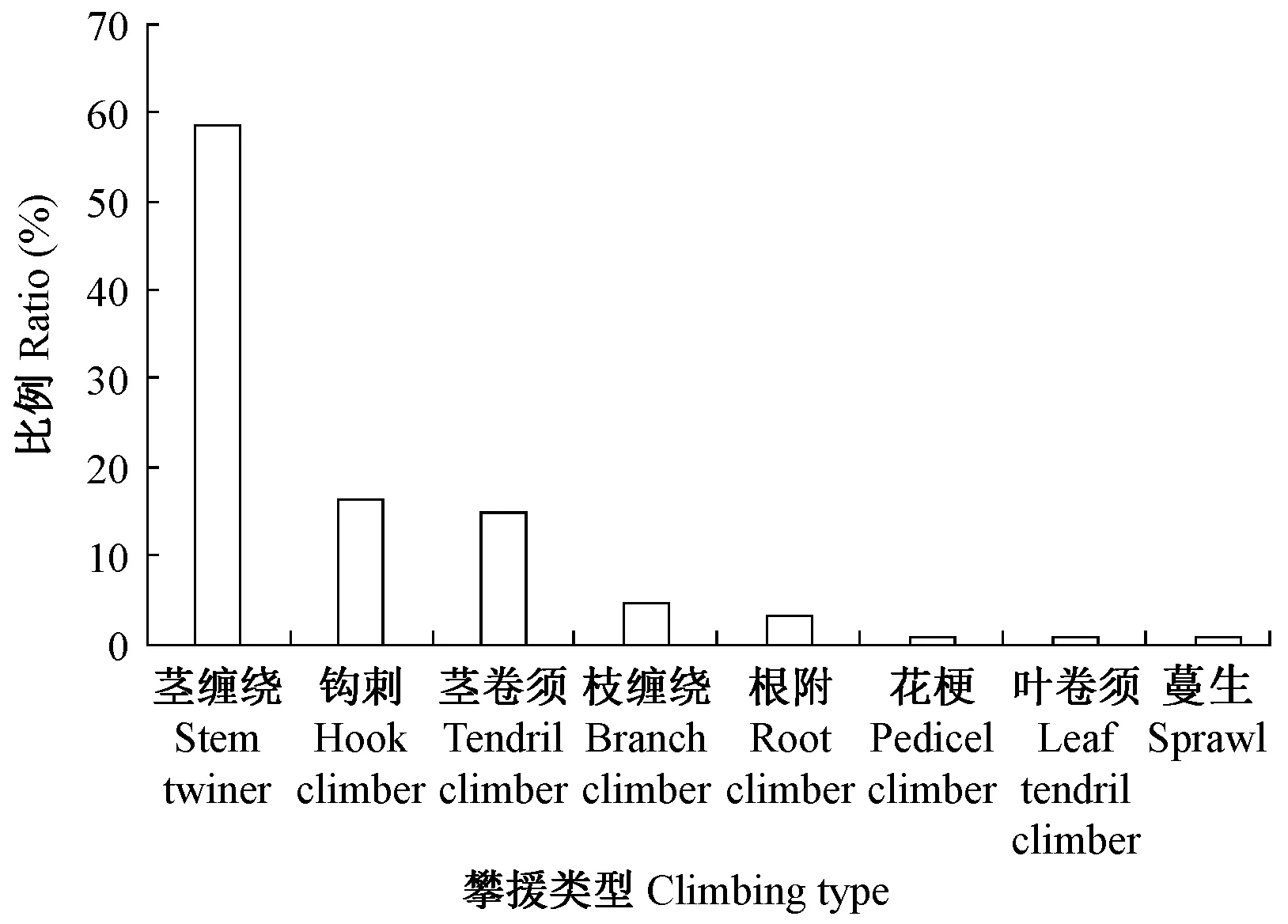

3.3攀援方式

在8类攀援方式中,依靠茎缠绕进行攀援的木质藤本所占比例最大,占木质藤本物种总数的58.6%,其次是钩刺攀援和卷须缠绕方式,分别占16.0%及15.0%; 而花梗、叶卷须、蔓生所占比例最小,每个类型仅有1种(图3)。此外,有的木质藤本利用多种攀援方式,例如眼镜豆(Entadarheedii)利用茎缠绕和叶卷须进行攀援。

图3 木质藤本攀缘类型百分比Fig.3 Percentage of liana climbing mechanisms

2.4树木被木质藤本攀援状况

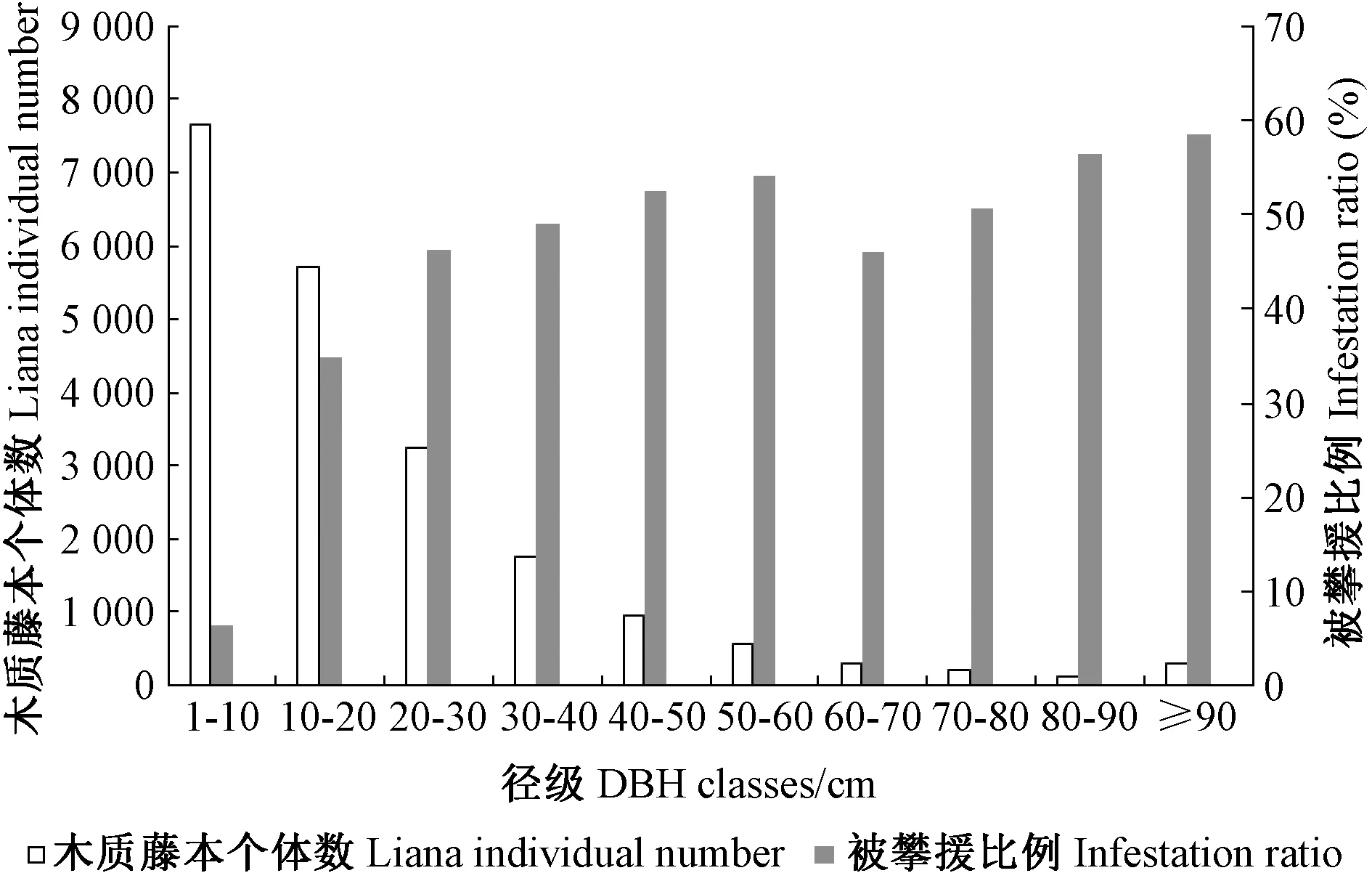

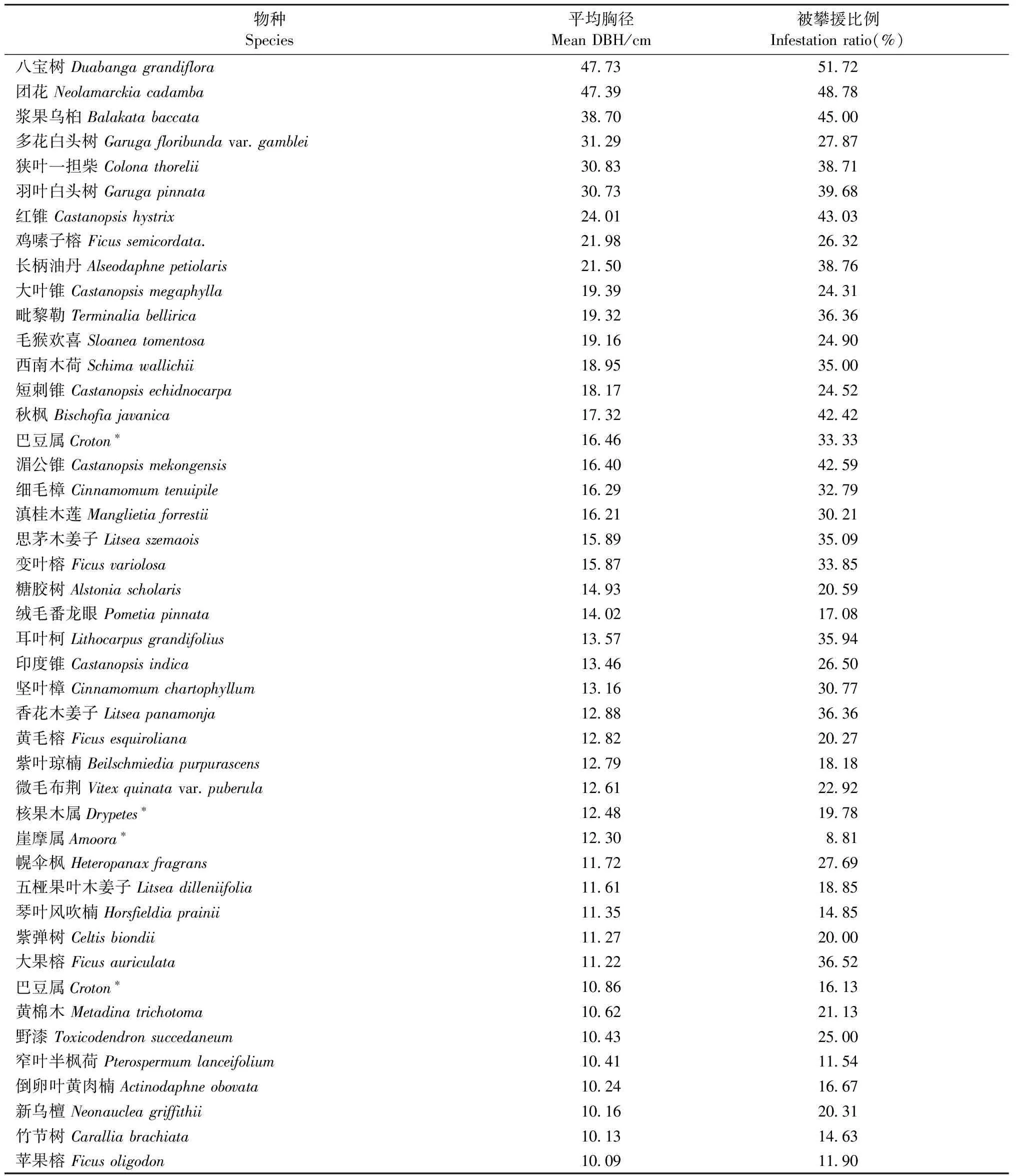

大样地中胸径≥1 cm的树木(95 834株)中共有10 221株被木质藤本攀援,比例为10.7%,被攀援树木种数达324种,占总树种数(468种)的69.2%。从整个大样地水平来看,随着树木径级增大,其上攀援的木质藤本数量逐渐降低,但是,随着树木径级增大,树木被木质藤本攀援的程度加剧,表现为被木质藤本攀援的比例增加(图4)。卡方检验结果显示不同树种间被攀援程度具有显著差异(χ2=245.782,df=44,P< 0.001)(表2)。

图4 不同径级树木上攀援的木质藤本株数及 被攀援比例Fig.4 The individuals of liana hosted and infestation ratio of trees across different DBH classes

3 讨论

西双版纳热带季雨林20 hm2动态监测大样地中鉴定木质藤本127种,占中国种子植物区系中木质藤本物种数的6.0%,在个体数和种数上分别占该样地中木本植物总数(乔木+木质藤本)的17.7%和21.5%。从全球来看,热带地区木质藤本约占森林木本种类25%,然而各大洲热带森林间木质藤本的丰富度存在显著差异(Putzetal., 1991; DeWaltetal., 2000; Parthasarathyetal., 2004)。西双版纳20 hm2样地木质藤本物种丰富度低于巴拿马和刚果盆地等典型热带雨林(Schnitzeretal., 2012; Ewangoetal., 2015),西双版纳地处热带北缘,与典型热带雨林相比,温度偏低,另外,西双版纳有较长的雾凉季,可能在一定程度上限制了木质藤本的生长。但是西双版纳地区干湿季明显,干湿季变化越明显的森林越有利于维持木质藤本的多样性(Schnitzer, 2005; Swaineetal., 2007; DeWaltetal., 2010),导致物种丰富度高于波多黎各、阿根廷等亚热带森林(Maliziaetal., 2010)。此外,干扰也有利于维持木质藤本多样性。本调查发现, 20 hm2样地有葛藤(Puerariamontana)等先锋木质藤本,表明该热带季雨林在历史上可能遭受较严重的干扰。这些因素使得西双版纳热带季雨林木质藤本维持了较高的多样性。

西双版纳20 hm2热带季雨林动态监测大样地中木质藤本的优势科为豆科和葡萄科,其次为夹竹桃科、梧桐科和番荔枝科,科水平的组成与热带亚洲热带雨林木质藤本相似,但与热带美洲、非洲的木质藤本组成存在明显差异。美洲热带雨林主要以紫葳科(Bignoniaceae)和豆科的木质藤本占优势,热带非洲以夹竹桃科和豆科的木质藤本占优势(Gentry, 1991)。夹竹桃科木质藤本在西双版纳热带季雨林中优势度较低的机制仍需深入研究。

表2 西双版纳热带季雨林20 hm2动态监测大样地中树木(DBH ≥ 10 cm,株数≥ 30)被木质藤本攀援的比例①Tab.2 Proportion of trees (DBH ≥ 10 cm, and ≥ 30 individuals) infested by lianas in Xishuangbanna 20 hm2 tropical seasonal rainforest dynamics big plot

①*: 未鉴定到种Unidentified to species level.

同其他热带森林的研究(陈亚军等, 2008; Schnitzeretal., 2012)相似,西双版纳20 hm2大样地中小径级木质藤本占优,而径级较大的木质藤本数量相对较少(图2)。本研究中胸径大于10 cm的个体数为151,平均7.6株·hm-2,略低于BCI 50 hm2样地(8.6株· hm-2)(Schnitzeretal., 2012)。本研究大样地中木质藤本最大胸径为24.5 cm,而在滇南勐宋热带山地雨林中木质藤本的最大胸径可达42.0 cm(陈亚军等, 2008),在BCI的50 hm2样地中,最大达到55.1 cm(Schnitzeretal., 2012)。有研究显示大型木质藤本的比例越高,森林年龄越大,所受干扰越少,进一步表明西双版纳20 hm2样地在历史上受干扰后恢复的时间可能还比较短。

热带雨林木质藤本具有多样的攀援方式。本研究发现,大样地中木质藤本主要以茎缠绕方式攀援宿主树木(图3),这与其他地区的研究结果(Nabe-Nielsen, 2001)一致。本研究中胸径大于10 cm的乔木被攀援的比例(27.1%)远低于其他地区的相关研究,如在阿根廷亚热带森林为65%(Maliziaetal., 2006),亚洲东南部为51%(Putzetal., 1987),巴拿马BCI为49%(Putz, 1984),可能原因是本样地内小径级木质藤本占优势,样地内树木具有较高重要值的几种树木的胸径都普遍较小(兰国玉等, 2008)。

本研究发现,在不同径级之间,树木胸径越大被攀援的可能性越高(表2)。Malizia等(2006)研究发现,林冠光照环境、树木大小与木质藤本攀援程度有关,其中林冠光照环境与藤本植物分布相关性更高。大径级树木往往比小径级树木攀附更多的木质藤本。当一株树被木质藤本缠绕之后,往往会增加其他木质藤本缠绕的可能性(Nabe-Nielsen, 2001; Prez-Salicrupetal., 2005)。此外,由于树木的直径往往与树龄密切相关,胸径越大往往意味着更长的生长期,有更多的机会被木质藤本选择和缠绕。木质藤本对大树的攀援可能对大树的生长乃至整个森林生态系统的功能造成不利影响。过度攀援将导致林冠被覆盖,光照条件受到影响,质量过大,容易折断和倒塌,损伤周围树木的正常生长。

4 结论

本研究报道了西双版纳热带季雨林中木质藤本的多样性、径级分布、攀援方式及其对共生树木的攀援情况,为加强森林管理提供了重要理论基础。下一步,将结合不同调查样方的地形、土壤理化特性深入研究热带季雨林木质藤本多样性的维持机制,结合树木普查数据深入探讨木质藤本的存在对热带季雨林更新、动态和碳固定等生态过程的影响。

陈亚军, 文 斌. 2008. 滇南勐宋热带山地雨林木质藤本多样性研究. 广西植物, 28(1): 67-72.

(Chen Y J, Wen B. 2008.Liana diversity and abundance of a tropical montane rainforest in Mengsong, Southern Yunnan, China. Guihaia, 28(1): 67-72. [in Chinese])

何云玲, 张一平, 杨小波. 2007. 中国内陆热带地区近40年气候变化特征. 地理科学, 27(4): 499-505.

(He Y L, Zhang Y P, Yang X B. 2007. Climate change in tropical area of southwestern China since 1950s. Scientia Geographica Sinica, 27(4): 499-505. [in Chinese])

胡 亮, 李鸣光, 李 贞. 2010. 中国种子植物区系中的藤本多样性. 生物多样性, 18(2):198-207.

(Hu L, Li M G, Li Z. 2010.The diversity of climbing plants in the spermatophyte flora of China. Biodiversity Science, 18(2):198-207. [in Chinese])

兰国玉, 胡跃华, 曹 敏, 等. 2008. 西双版纳热带森林动态监测样地-树种组成与空间分布格局. 植物生态学报, 32(2): 287-298.

(Lan G Y, Hu Y H, Cao M,etal. 2008. Establishment of Xishuangbanna tropical forest dynamics plot: species compositions and spatial distribution patterns. Journal of Plant Ecology, 32(2): 287-298. [in Chinese])

朱 华. 2011. 云南热带季雨林及其与热带雨林植被的比较. 植物生态学报, 35(4): 463-470.

(Zhu H. 2011. Tropical monsoon forest in Yunnan with comparison to the tropical rain forest. Chinese Journal of Plant Ecology, 35(4): 463-470. [in Chinese])

Chave J, Riéra B, Dubois M A. 2001. Estimation of biomass in a neotropical forest of French Guiana: spatial and temporal variability. Journal of Tropical Ecology, 17(1): 79-96.

Darwin C. 1865. On the movements and habits of climbing plants. Journal of the Linnean Society of London (Botany), 9(33 /34): 1-118.

DeWalt S J, Schnitzer S A, Denslow J S. 2000. Density and diversity of lianas along a chronosequence in a central Panamanian low land forest. Journal of Tropical Ecology, 16(1): 1-19.

DeWalt S J, Schnitzer S A, Chave J,etal. 2010. Annual rainfall and seasonality predict pan-tropical patterns of liana density and basal area. Biotropica, 42(3): 309-317.

Ewango C E N, Bongers F, Makana J R,etal. 2015. Structure and composition of the liana assemblage of a mixed rain forest in the Congo Basin. Plant Ecology and Evolution, 148(1): 29-42.

Gentry A. 1991. Breeding and dispersal systems of lianas. The biology of vines. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 393-423.

Gerwing J J, Farias D L. 2000.Integrating liana abundance and forest stature into an estimate of total aboveground biomass for an eastern Amazonian forest. Journal of Tropical Ecology, 16(3): 327-335.

Greig-Smith P. 1983. Quantitative plant ecology. London: Blackwell Scientific Publications.

Hu Y H, Sha L Q, Blanchet F G, et al. 2012. Dominant species and dispersal limitation regulate tree species distributions in a 20-ha plot in Xishuangbanna, southwest China. Oikos, 121(6): 952-960.

Hubbell S P, Foster R B. 1986. Commonness and rarity in a neotropical forest: implications for tropical tree conservation. Conservation Biology: science of scarcity and diversity. Sunderland, UK: Sinauer Press, 205-231.

Ichihashi R, Tateno M. 2015. Biomass allocation andlong-term growth patterns of temperate lianas in comparison with trees. New Phytologist, 207(3): 604-612.

Kusumoto B, Enoki T. 2008. Contribution of a liana species,MucunamacrocarpaWall., to litterfall production and nitrogen input in a subtropical evergreen broad-leaved forest. Journal Forest Research, 13(1): 35-42.

Laurance W F, Ferreira L V,Rankin-de Merona J M,etal. 1998. Rain forest fragmentation and the dynamics of Amazonian tree communities. Ecology, 79(6): 2032-2040.

Magurran A E.1988. Ecological diversity and its measurement. London: Croon Helm Limited.

Malizia A, Grau H R. 2006.Liana-host tree associations in a subtropical montane forest of north-western Argentina. Journal of Tropical Ecology, 22(3): 331-336.

Malizia A H, Ricardo G, Lichstein J W. 2010. Soil phosphorus and disturbance influence liana communities in a subtropical montane forest. Journal of Vegetation Science, 21(3): 551-560.

Nabe-Nielsen J. 2001. Diversity and distribution of lianas a neotropical rain forest, Yasuni National Park, Ecuador. Journal of Tropical Ecology, 17(1): 1-19.

Parthasarathy N, Muthuramkumar S, Reddy M S. 2004. Patterns of liana diversity in tropical evergreen forests of peninsular India. Forest Ecology and Management, 190(1): 15-31.

Prez-Salicrup D R, Meijere W D. 2005. Number of lianas per tree and number of trees climbered by lianas at Los Tuxtlas, Mexico. Biotropica, 37(1): 153-156.

Putz F E. 1983. Liana biomass and leaf area of a tierrafirme forest in the Rio Negro basin, Venezuela. Biotropica, 15(3): 185-189.

Putz F E. 1984. The natural history of lianas on Barro Colorado Island, Panama. Ecology, 65(6): 1713-1724.

Putz F E, Chai P. 1987.Ecological-Studies of lianas in Lambir National-Park, Sarawak, Malaysia. Journal of Ecology, 75(2): 523-531.

Putz F E, Mooney H A. 1991. The Biology of Vines. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 73-97.

Schnitzer S A, Bongers F. 2002. The ecology of lianas and their role in forests. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 17(5): 223-230.

Schnitzer S A. 2005. A mechanistic explanation for global pattern of liana abundance and distribution. The American Naturalist, 166(2): 262 -276.

Schnitzer S A, DeWalt S J, Chave J. 2006. Censusing and measuring lianas: a quantitative comparison of thecommon methods. Biotropica, 38(5): 581-591.

Schnitzer S A, Rutishauser S, Aguilar S. 2008. Supplemental protocol for censusing lianas. Forest Ecology and Management, 255(3-4): 1044-1049.

Schnitzer S A, Carson W P. 2010. Lianas suppress tree regeneration and diversity in treefall gaps. Ecology Letters, 13(7): 849-857.

Schnitzer S A, Bongers F. 2011. Increasing liana abundance and biomass in tropical forests: emerging patterns and putative mechanisms. Ecology Letters, 14(4): 397-406.

Schnitzer S A, Mangan S A, Dalling J W,etal. 2012. Liana abundance, diversity, and distribution on Barro Colorado Island, Panama. PLOS One, 7(12): e52114.

Swaine M D, Grace J. 2007. Lianas may be favoured by low rainfall: evidence from Ghana. Plant Ecology, 192(2): 271-276.

van der Heijden G M F, Powers J S, Schnitzer S A. 2015. Lianas reduce carbon accumulation and storage in tropical forests. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 112(43): 13267-13271.

Wright S J, Sun I F, Pickering M,etal. 2015. Long-term changes in liana loads and tree dynamics in a Malaysian forest. Ecology, 96(10): 2748-2757.

(责任编辑 于静娴)

LianaDiversityanditsClimbingSituationonTreesinXishuangbannaTropicalSeasonalRainforest

Liu Qi1, 2Wu Huaidong1, 2Tan Yunhong1Zhang Jiaolin1

(1.XishuangbannaTropicalBotanicalGarden,ChineseAcademyofSciencesMengla666303; 2.UniversityofChineseAcademyofSciencesBeijing100049)

S718.5

A

1001-7488(2017)08-0001-08

10.11707/j.1001-7488.20170801

2016-01-25;

2017-07-05。

国家自然科学基金项目(31270453,31470470)。

*张教林为通讯作者。