果品及其制品展青霉素污染的发生、防控与检测

聂继云

(中国农业科学院果树研究所/农业部果品质量安全风险评估实验室(兴城)/农业部果品及苗木质量监督检验测试中心(兴城),辽宁兴城 125100)

食品科学与工程

果品及其制品展青霉素污染的发生、防控与检测

聂继云

(中国农业科学院果树研究所/农业部果品质量安全风险评估实验室(兴城)/农业部果品及苗木质量监督检验测试中心(兴城),辽宁兴城 125100)

展青霉素是由青霉属、曲霉属、丝衣霉属等真菌产生的一种聚酮类次生代谢产物,广泛存在于果品及其制品中,苹果及其制品是主要污染源,也是人类膳食中展青霉素最主要的来源。展青霉素有各种急性、慢性和细胞水平的危害。国际组织和不少国家均制定了果品及其制品中展青霉素限量。扩展青霉是最主要的产展青霉素真菌,能污染许多种果品及其制品。扩展青霉地域分布甚广,许多国家均分离到了其菌株。作为植物病原菌,扩展青霉往往通过果实上的伤口如受伤部位、害虫为害部位、病菌感染部位,以及果柄、开放的萼筒、皮孔等部位入侵。过熟和长期贮藏的水果更易感染扩展青霉。扩展青霉是一种好寒性霉菌,在 0℃生长旺盛。展青霉素生物合成通路约由10步构成,棒曲霉和扩展青霉中展青霉素生物合成基因簇包含相同的15个基因,但两者基因序列差异很大。展青霉素的细胞毒性和遗传毒性归因于其与细胞中亲核物质的高反应活性,主要通过共价键与细胞的亲核物质,特别是与蛋白质和谷胱甘肽的巯基结合,从而发挥毒性、破坏染色体和致突变。在其反应通路中,1个展青霉素分子最多可与3个谷胱甘肽分子反应。采前措施、采后处理和贮藏条件对控制展青霉素污染及其产毒真菌至关重要。使用化学杀菌剂是重要的防控策略,但过度使用杀菌剂会导致抗性菌株出现。使用“低风险杀菌剂”则能降低产生抗药性的风险。生物防治是化学防治的替代方法或补充,可减少甚至避免使用杀菌剂。清洗、分选、整理等加工工艺有助于消减水果制品中的展青霉素污染。液液萃取和固相萃取是果品及其制品中展青霉素的经典提取方法,但液液萃取成本高、耗时、不适于固体样品。近年来,又研究建立了分散液液微萃取、盐析旋涡辅助液液微萃取、基质固相分散萃取、QuEChERS等提取方法。展青霉素通常用配紫外检测器或二极管阵列检测器的液相色谱仪进行定量,采用液相色谱串联质谱、气相色谱串联质谱等仪器进行定性。另外,PCR具有快速、专一的特点,可用于对潜在的产展青霉素真菌进行早期检测。

果品;果品制品;展青霉素;污染;发生;防控;检测

Abstract:Patulin is a secondary metabolite of polyketide lactone mainly produced by species of Penicillium, Aspergillus, and Byssochylamys. It was found as a contaminant in many fruits and fruit products, the major sources of contamination are apples and apple products, which are also the most important source of patulin in human diet. Patulin has various acute and chronic effects and others at the cellular level. Today, international organizations (Codex Alimentarius Commission and European Union) and many countries across the world have set maximum levels of patulin content in fruit and fruits products. Among the different genera, themost important patulin producer is P. expansum, it can contaminate a number of fruits and fruit products, and produce mycotoxin patulin. P. expansum distributes very extensively, its strains have been isolated from many countries. As a plant pathogen, P.expansum penetrates fruits typically through wounds or injuries produced during harvest and handling, it can also penetrate through stem end, open calyx tube and lenticels of fruits, and infection sites of other primary fruit pathogens. Overmature or long-stored fruits are more susceptible to P. expansum infection. P. expansum is a psychrophile, its growth is quite strong at 0℃. The biosynthetic pathway of patulin consists of approximately 10 steps. It has been clarified that both of the patulin biosynthetic gene cluster from P.expansum and that from A. clavatus composed of the same 15 genes, but their gene sequences differed greatly. The genotoxic and cytotoxic properties of patulin are due to its high reactivity to cellular nucleophiles. Patulin is believed to exert its toxic,chromosome-damaging, and mutagenic activity mainly by covalent binding to cellular nucleophiles, in particular to the thiol groups of proteins and glutathione (GSH). In the major reaction pathways, up to three molecules of glutathione can bind to one molecule patulin. To control the contamination of patulin and the growth of moulds producing it, pre-harvest measures, post-harvest treatments,and storage conditions deserve special attention. The use of chemical fungicides is an important strategy, but the overuse of fungicides will lead to the emergence of fungicide-resistant strains. Because their way of action reduces the risk of resistant population emergence, “low risk fungicides” are more suitable and efficient. Using biocontrol agents are alternative or complementary treatments that permit to decrease fungicide doses or even avoid the use of chemicals. Some stages of manufacturing process (such as washing, sorting and trimming) are highly efficient in reducing the levels of patulin in fruit products. Liquid-liquid extraction (LLE) and solid-phase extraction (SPE) are classical methods to extract patulin in fruits and fruit products. However, LLE is expensive, time consuming, and unsuitable for the treatment of solid sample. In the last years, some other extraction measures have been studied and developed, including DLLME, IL-DLLME, BS-DLLME, salting out-VALLME, MSPD, and QuEChERS. LC-UV or LC-DAD procedure is routinely used for quantitative determination of patulin, and methods to confirm the presence of patulin usually include more specific detection techniques such as LC-MS/MS and GC-MS/MS. PCR method is a fast and specific method of early detecting the potential patulin producing fungi.

Key words:fruit; fruit product; patulin; contamination; occurrence; control; determination

0 引言

展青霉素(patulin,PAT)也叫棒曲霉素,为真菌次生代谢产物[1]。展青霉素最早于20世纪40年代作为抗生素分离自灰黄青霉(Penicillium griseofulvum)和扩展青霉(P. expansum)[2]。许多早期研究都针对其抗菌活性的利用,例如用于治疗普通感冒和皮肤真菌感染[3-4]。20世纪50年代和60年代,情况变得明了,除抗菌、抗病毒和抗原生动物外,展青霉素对植物和动物也有毒性,排除了其作为抗生素的临床用途,1960年代被重新分类为毒素[5]。展青霉素广泛存在于果品和果品制品中,对人体健康和经济造成严重影响[6],其含量可达数百ppb[7-8],甚至高达1 650 ppb[9]。其中,水果包括苹果[1-2,7-18]、梨[2,7,12-15,17,19]、葡萄[7,10,12-15,17,19]、桃[7,13,15,17,19]、樱桃[13,15]、李子[13,15]、杏[7,12-15,17,19]、草莓[12-13,15,19]、桑葚[15]、猕猴桃[15]、油桃[15]、橄榄[15]、蓝莓[19]、黑穗醋栗[13]、榅桲[11,14]、橙子[13]、芒果[12]、菠萝[13]、香蕉[12-13]、榛子[20]等;水果制品以苹果汁为主[1-2,11-14,16-19,21-29],此外,还有梨汁[8,12-13,16,21,28-29]、葡萄汁[24-25,28]、桃汁[13,16,29]、樱桃汁[28]、杏汁[25,29]、橙汁[24-25,28]、菠萝汁[25,28]、荔枝汁[25]、西番莲汁[28]、黑穗醋栗汁[28]、混合果汁[8,25,30]、水果饮料[29]、苹果酒[1-2,12,28]、葡萄酒[31]、苹果酱[8]、梨酱[8]、草莓酱[28]、蓝莓酱[28]、黑穗醋栗酱[28]、榅桲酱[11]、苹果泥[1,12-13,16,18,23,28]、梨泥[13]、桃泥[13]、苹果沙司[1]、无花果干[21]等。苹果及其制品是主要污染源,也是人类膳食中展青霉素最主要的来源[28]。除单独污染外,展青霉素还能与桔青霉素和黄曲霉毒素共生,例如,苹果中与桔青霉素共生[10],榛子中与黄曲霉毒素(B1、B2、G1、G2)共生[20]。

1 展青霉素的主要特性

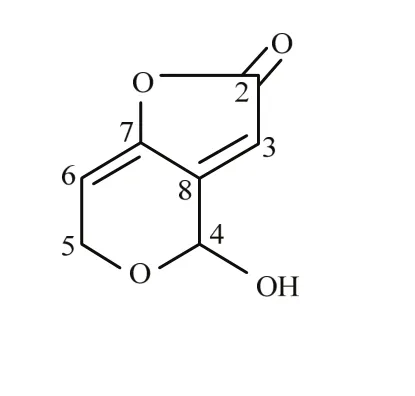

展青霉素为无色针状结晶,熔点110.5—112℃,易溶于水、乙醇、丙酮、乙酸乙酯和氯仿,微溶于乙醚和苯,不溶于石油醚,最大紫外吸收波长276 nm;酸性条件下较稳定,碱性条件下不稳定[32-33]。pH 3.3—5.5水溶液中的展青霉素在 105℃—125℃下稳定,因此,热处理(巴氏杀菌)不能使苹果制品(如苹果汁、苹果酒)中的展青霉素完全失活[26]。与黄曲霉毒素、伏马毒素、赭曲霉素等主要真菌毒素一样[2],展青霉素也是聚酮类代谢产物[2,34-35],为一种高反应活性[29]α,β-不饱和 γ-内酯[36],分子式为 C7H6O4,分子量为154,化学名称为4-羟基-4氢-呋喃[3,2-碳]吡喃-2[6 氢]-酮[26],化学结构[1]见图 1。

图1 展青霉素的化学结构[1]Fig. 1 Chemical structure of patulin[1]

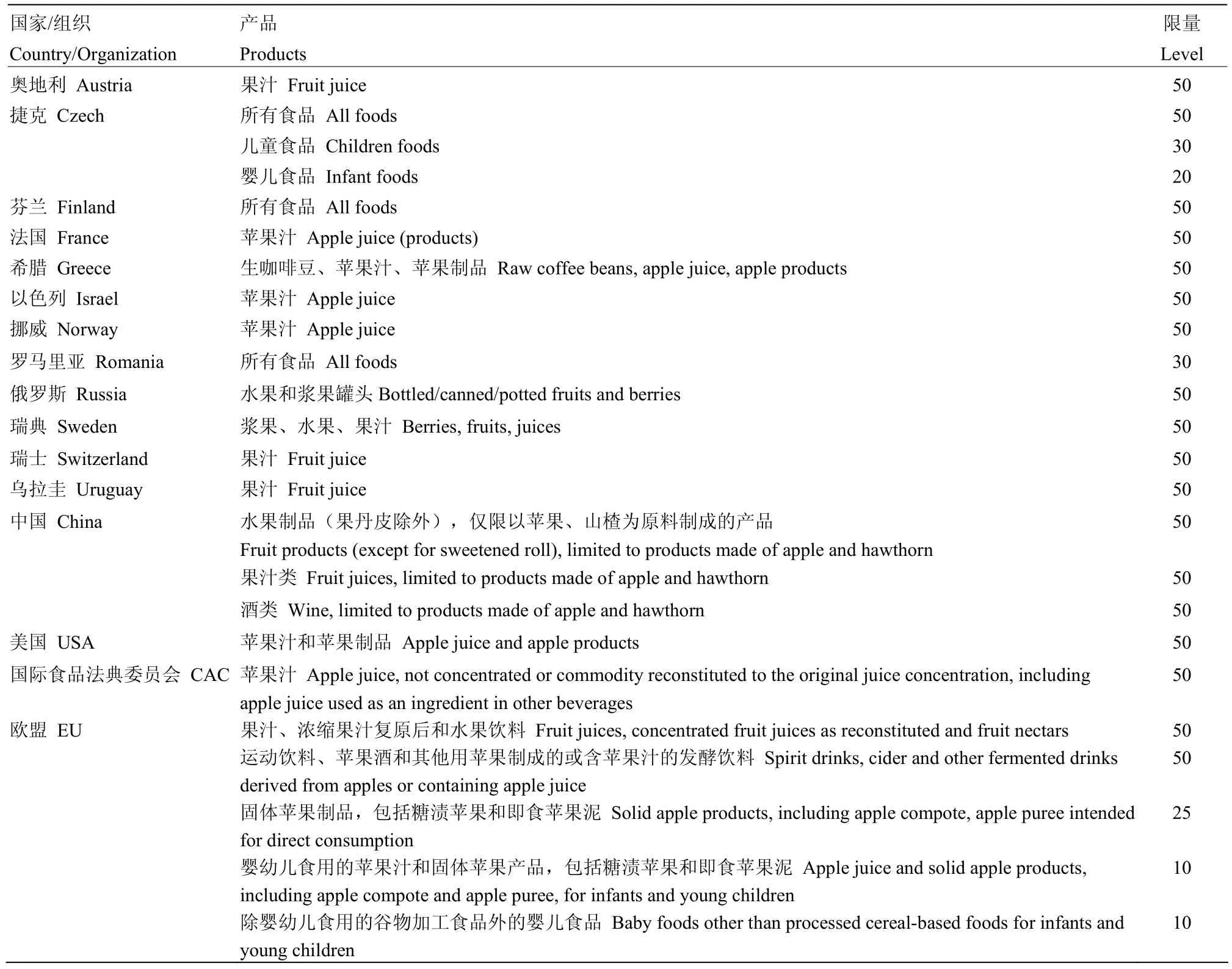

展青霉素属中等毒性物质,雄鼠经口 LD50为 35 mg·kg-1[37];暂定最大耐受日摄入量(PMTDI)成人为0.4 μg·(kg bw)-1[8,25,30,38-41]、儿童为 0.2μg·(kg bw)-1[8,25,30],该摄入量依据展青霉素的最大无作用量(NOEL)43 μg·(kg bw)-1和安全系数100制定[39,42]。国际组织(国际食品法典委员会[43]、欧盟[44])和不少国家均制定了食品中展青霉素限量[1,11,45](表1)。展青霉素是可能致癌物[1],国际癌症研究中心将其归入第3类物质[46],即对人体致癌性尚未归类的物质[47]。展青霉素对动物有各种急性、慢性和细胞水平的危害[27-28,48]。急性症状包括紧张、抽搐、肺充血、水肿、充血、胃肠道扩张、肠出血和上皮细胞变性。慢性症状包括遗传毒性、神经毒性、免疫毒性、免疫抑制、致畸和致突变。细胞水平的危害有原生质膜破裂以及蛋白质、DNA和RNA合成受抑制等。展青霉素对高等植物也有毒[28],例如,能抑制种子萌发[3,49]和引起植株萎蔫[3],对植物(伊乐藻和番茄)原生质体流动有强抑制作用[3],可导致春小麦节间长度、小花数、种子重量和种子数减少[50]。展青霉素对微生物的毒性也有报道。它能抑制革兰氏阴性细菌和革兰氏阳性细菌的生长,人们测试了超过75种细菌,无一能完全抵抗其毒性[3];展青霉素还能抑制酵母的生长[51]。

表1 国际组织和一些国家制定的食品中展青霉素限量(μg·kg-1或μg·L-1)Table 1 Maximum levels (μg·kg-1or μg·L-1) established by countries and international organizations

2 展青霉素的发生流行

展青霉素由曲霉属(Aspergillus)、丝衣霉属(Byssochlamys)、拟青霉属(Paecilomyces)、青霉属(Penicillium)等真菌产生[2,52],丝衣霉是无性型拟青霉[36]。曲霉属中的棒曲霉(A. clavatus)、巨曲霉(A.giganteus)、A. longivesica,青霉属中的P. carneum、棒束青霉(P. clavigerum)、嗜粪青霉(P.concentricum)、P. coprobium、P. dipodomyicola、扩展青霉、栎实青霉(P. glandicola)、唐菖蒲青霉(P.gladioli)、灰黄青霉、P. marinum、P. paneum、P.sclerotigenum、狐粪青霉(P. vulpinum),丝衣霉中的雪白丝衣霉(B. nivea),以及拟青霉中Paecilomyces saturatus的某些菌株,均能产生展青霉素[2,52]。据报道[53],中国青霉属真菌中橘灰青霉(P. aurantiogriseum)、扩展青霉、栎实青霉、灰黄青霉、多毛青霉(P.hirsutum)、杨奇青霉(P. janczewskii)、梅林青霉(P.melinii)、娄地青霉(P. roqueforti)、小刺青霉(P.spinulosum)、狐粪青霉等均能产生展青霉素。

图2 被扩展青霉污染的苹果[2,36]Fig. 2 Apples contaminated by P. expansum[2,36]

扩展青霉是食品中展青霉素的主要来源[28,54]。通常,水果(特别是苹果)受该病菌影响最大,被认为是到目前为止,展青霉素进入食物链的主要途径[55-56]。扩展青霉寄主极广,能侵染苹果[7,15-16,22-24,26,28,57-59]、梨[7,15,22-24,26,28,57-59]、杏[7,15,24,26,28,57-59]、桃[7,15,26,28,57,59]、葡萄[7,15,23-24,26,28,59]、樱桃[15,22,28,58]、草莓[15,28,57]、香蕉[24,28]、油桃[15,28]、李子[15,28]、桑葚[15,28]、猕猴桃[15,57]、黑穗醋栗[28,58]、薄壳山核桃[28,58]、榛子[28,58]、菠萝[24]、橙子[24]、树莓[28]、柿子[28]、蓝莓[28]、青梅[59]、杏仁[28]、榅桲[58]、花楸浆果[58]、橡实[58]、核桃[58]、橄榄[15,59]等果品,以及苹果汁、梨汁、葡萄汁、樱桃汁、醋栗汁、草莓酱、梨泥等果品制品[15,58-59],并产生展青霉素。扩展青霉地域分布甚广,欧洲、美洲、亚洲、大洋洲和非洲的许多国家均分离到了其菌株[53,58,60]。中国青霉属真菌中,狐粪青霉罕见,梅林青霉、多毛青霉和栎实青霉较罕见,余者均分布广或较广[53]。另外,果品及其制品展青霉素污染存在地区差异。以报道最多的苹果汁为例,中国陕西生产的苹果汁其展青霉素含量平均仅为8.44 μg·kg-1[17],西班牙加泰罗尼亚地区销售的苹果汁展青霉素含量略高于该水平(平均含量11.7 μg·kg-1)[18],而南非[9]和突尼斯[8]的苹果汁展青霉素污染情况则要严重得多,展青霉素平均含量分别高达 210 μg·kg-1和 45.7 μg·kg-1。

扩展青霉能引起苹果、梨、樱桃、杏、猕猴桃、桃等许多水果发生青霉病[57,61-63],造成贮藏期和货架期损失[64]。果实发病后,出现褐色软腐,产生绿色或蓝色分生孢子梗和分生孢子,形成脓疱[2,36](图2)。扩展青霉往往通过伤口或受伤部位侵入,也可通过果柄、开放的萼筒和皮孔侵入,还可从果实上害虫为害部位和其他病原菌感染部位侵入[27,65]。采前产生的伤口和采收、分级、包装、贮藏、运输过程中造成的机械伤是扩展青霉的重要入侵点[66],任何机械损伤都会增加果实感染扩展青霉的敏感性[27]。过熟或长期贮藏的水果更容易感染扩展青霉[67]。对于树上的果实,即使上面有扩展青霉分生孢子,果实采收前这些分生孢子通常也不会生长,但这些果实如果受到病虫为害或掉落地上,果实采收后就可能发病,并产生展青霉素[27]。扩展青霉的生长主要受温度以及 O2和 CO2浓度等环境条件的影响[37]:作为一种好寒性霉菌,扩展青霉生长温度最低可达-6℃,在 0℃下生长强劲,最适生长温度为25℃,最高生长温度为35℃;扩展青霉对O2要求低,即使O2浓度低至2.1%,其生长也几乎不受影响;空气中的CO2能刺激扩展青霉生长,CO2浓度高至15%仍有刺激作用,但较高的CO2浓度会使扩展青霉生长速率降低。

图3 展青霉素生物合成通路[2]Fig. 3 Scheme of patulin biosynthetic pathways[2]

3 展青霉素的生物合成

展青霉素的生物合成通路(图3)约由10步构成[2]。现已明确棒曲霉和扩展青霉中的展青霉素生物合成基因簇,均包含相同的15个基因[35,68],但两者基因序列差异很大(图 4)。扩展青霉中的展青霉素生物合成基因簇聚集在一个41 kb的DNA区域。其中,PatL编码一个转录因子;PatM、PatC和PatA编码转运蛋白;PatB编码羧酸酯酶;PatD编码依赖Zn的乙醇脱氢酶;PatE编码葡萄糖-甲醇-胆碱(GMC)氧化还原酶(该酶催化展青霉素生物合成通路的最后一步,即由ascladiol生成展青霉素);PatG编码一个脱羧酶(即6-甲基水杨酸脱羧酶[69],该酶呈现一个氨基羟化酶保守域,极有可能参与了6-甲基水杨酸脱羧生成间甲酚的过程);PatH和PatI编码细胞色素P450(P450负责间甲酚羟化为间羟基苯甲醇和间羟基苯甲醇羟化为龙胆醇);PatJ编码一个加双氧酶;PatK是扩展青霉的展青霉素生物合成基因簇中的骨干基因,编码6-甲基水杨酸聚酮合成酶(6-MSAS);PatN编码isoepoxydon脱氢酶;PatO编码异戊醇氧化酶;PatF功能未知,有一个类似SnoaL的结构域。虽然意大利青霉(P. italicum)和指状青霉(P. digitatum)中也发现了展青霉素基因的直系同源物,但均无骨干基因PatK,且意大利青霉中仅鉴定出了 PatC、PatD和PatL 3个基因,这两种青霉菌都不产生展青霉素[68]。

图4 扩展青霉和棒曲霉中展青霉素基因簇示意图[35]Fig. 4 Schematic representation of the patulin gene clusters in P. expansum and A. clavatus[35]

4 展青霉素的作用机制

展青霉素的遗传毒性和细胞毒性是由于其与细胞亲核物质的高反应活性[70]。展青霉素与蛋白质和谷胱甘肽[71-72]的巯基反应快,而与氨基[73]的反应要慢得多。在高浓度展青霉素处理的中国仓鼠V79肺成纤维细胞中观察到了 DNA链断裂、DNA氧化性修饰和DNA-DNA铰链,证明在细胞系统中展青霉素直接与DNA反应[72]。展青霉素诱导细胞遗传损伤的机制[70]是交链的姐妹染色单体在有丝分裂期没有很好地分离,被拉到相反的两极,形成后期桥,后期桥在胞质分裂期转变为核质桥;DNA损伤引起的细胞周期紊乱导致中心体扩增,产生多极纺锤体;阴性着丝粒微核通过核质桥断裂产生或在铰链 DNA修复和复制过程中产生,而阳性着丝粒微核则可能是有丝分裂紊乱的结果。展青霉素是致突变真菌毒素,特别是在谷胱甘肽浓度低的细胞中[74]。例如,展青霉素处理的人体肝癌HepG2细胞[75]和中国仓鼠V79肺成纤维细胞[46]染色体畸变率增加;展青霉素能诱导中国仓鼠V79肺成纤维细胞产生阴性着丝粒微核和阳性着丝粒微核[71]。

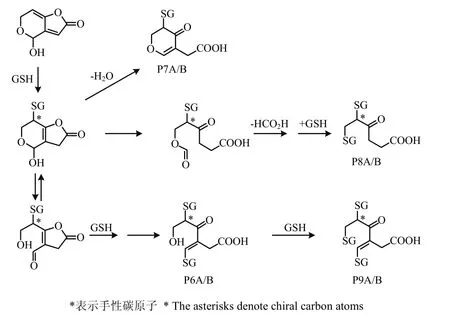

展青霉素的细胞毒性模式是通过C-6和C-2不饱和杂环内酯与蛋白质、酶和其他细胞成分的巯基相互作用,破坏细胞功能[72,76]。展青霉素主要通过共价键结合到细胞的亲核物质上,特别是结合到蛋白质和谷胱甘肽(GSH)的巯基上[71,77-78],从而发挥毒性[79-80]、破坏染色体[46,71,81]和致突变[74]。展青霉素与谷胱甘肽反应的主要通路和加合物结构见图5,图中*表示手性碳原子[76],加合物的命名按文献[82]进行。由图5可知,一个展青霉素分子可与多达3个谷胱甘肽分子结合。展青霉素最初与一个巯基反应形成的加合物比展青霉素本身具有更高的与巯基和氨基的反应活性,但有两个或三个巯基的加合物没有或仅有较低的进一步反应活性[82]。谷胱甘肽发挥着展青霉素防护剂的作用[72,83],其与展青霉素反应的加合物可用高效液相色谱(HPLC)结合生化检测器(BCD)和电喷雾离子化串联质谱(ESI-MS/MS)的方法加以检测[38]。外源性抗氧化剂维生素E对展青霉素引起的遗传毒性和细胞毒性有防御作用[75]。而谷胱甘肽合成抑制剂丁硫氨酸亚砜亚胺(BSO)则会引起细胞谷胱甘肽含量减少,从而增加展青霉素的细胞毒性和遗传毒性[74,83]。

5 展青霉素的污染防控

使用化学杀菌剂是控制农产品采后真菌病害的重要策略[29,84-86],但因对公众健康的关注,采后化学药剂使用要求越来越严,英国禁止采后使用杀菌剂[40],在欧洲和美国,一些最有效的杀菌剂已被取消[29]。过度使用杀菌剂会导致抗杀菌剂菌株的出现[87]。咯菌腈抑制扩展青霉分生孢子萌发和菌丝体生长[88],能降低扩展青霉产生抗药性的风险,被称为低风险杀菌剂[89]。病菌的不同种群对同一种杀菌剂的敏感性有差异,为保证防控效果,可多种杀菌剂活性成分混合使用[87]。由于抗性菌株的发展,一些杀菌剂已失去效力[29,89-91],宜用敏感杀菌剂代替。例如,不少扩展青霉菌株已对噻菌灵产生抗性[92-93],而抗噻菌灵的扩展青霉分离株对抑霉唑敏感[92];咯菌腈能控制抗噻菌灵扩展青霉引起的青霉病[94]。因此,可用抑霉唑或咯菌腈替代噻菌灵。有的杀菌剂甚至还会促进病菌的发展和展青霉素的产生,应避免使用。例如,噻菌灵能刺激扩展青霉孢子的形成,进而促进扩展青霉的繁殖[95];多菌灵、克菌丹和乙嘧酚磺酸酯能刺激某些扩展青霉菌株产生展青霉素[96]。一些杀菌剂替代品也有很好的防治效果。3%次氯酸钠溶液浸果5 min能完全抑制受感染苹果中互隔交链孢霉(Alternaria alternata)、黄曲霉(A. flavus)、黑曲霉(A. niger)、枝孢样枝孢霉(Cladosporium cladosporioides)、镰刀霉(Fusarium)、扩展青霉和桃软腐病菌(Rhizopus stolonifer)在 25℃下的生长和为害[97]。2%—5%的醋酸溶液能抑制苹果上扩展青霉的生长和展青霉素的产生[55]。

图5 展青霉素与谷胱甘肽反应的主要通路[76]Fig. 5 Major pathways of the reaction of patulin with GSH[76]

生物防治是化学防治的替代方法或补充,可减少甚至避免使用杀菌剂[90]。使用微生物拮抗剂控制水果采后病害是最有前途的杀菌剂替代方案[98-99]。水果表面存在细菌、酵母等微生物群落,对扩展青霉有显著的拮抗活性[84,100]。有的生防剂其效果可与杀菌剂[29,100]、气调贮藏结合杀菌剂相媲美[87]。研究表明,清酒假丝酵母(Candida sake)[90,100]、西弗假丝酵母(Candida ciferrii)[62]、浅白隐球酵母(Cryptococcus albidus)[101]、罗伦隐球酵母(Candida laurentii)[62,102]、植物乳杆菌(Lactobacillus plantarum)[40]、乳酸菌(Lactic acid bacteria)[103]、核果梅奇酵母(Metschnikowia fructicola)[29]、成团泛菌(Pantoea agglomerans)[90]、卡利比克毕赤酵母(Pichia caribbica)[48]、荧光假单胞菌(Pseudomonas fluorescens)[99]、水拉恩氏菌(Rahnella aquatilis)[104]、胶红酵母(Rhodotorula mucilaginosa)[105]等拮抗菌对苹果上的扩展青霉都有显著防效。生防剂与低风险杀菌剂结合使用效果更好[89],如生防酵母结合啶酰菌胺和嘧菌环胺[106]、丁香假单胞菌(Pseudomonas syringae)结合嘧菌环胺[89]等。许多拮抗菌能降解展青霉素,将其转化为ascladiol、desoxypatulinic acid等毒性更低的物质[107-109],可用于展青霉素污染处理[110],如动物双歧杆菌(Bifidobacterium animalis)[111]、植物乳杆菌[40]、美极梅奇酵母(Metschnikowia pulcherrima)和核果梅奇酵母[29]、卡利比克毕赤酵母[48]、奥默毕赤酵母(Pichia ohmeri)[112]、粘红酵母(Rhodotorula glutinis)[113]、酿酒酵母(Saccharomyces cerevisiae)[107,114]、氧化葡糖杆菌(Gluconobacter oxydans)[108]、红冬孢酵母(Rhodosporidium kratochvilovae)[109]、沼泽生红冬孢酵母(Rhodosporidium paludigenum)[115]等。屎肠球菌(Enterococcus faecium)能与展青霉素结合而将其从水溶液中清除[116]。一些植物源性成分也有很好的防效。柚皮苷、橙皮苷、新橙皮苷、樱桃苷、橙皮素葡萄糖苷等黄烷酮及其葡萄糖苷酯能抑制扩展青霉、土曲霉(A. terreus)和黄褐丝衣菌(B. fulva)产生展青霉素,使其积累量减少95%以上[26]。槲皮素和伞形花内酯能控制扩展青霉生长和展青霉素积累,可代替传统化学杀菌剂,用于苹果采后青霉病的防控[41,117]。0.2%柠檬精油和 2%橙子精油均对抑制苹果中扩展青霉产生展青霉素有非常好的效果[97]。

采前措施、采后处理和贮藏条件对控制产展青霉素真菌生长和展青霉素污染十分重要。以苹果为例,为保证果品质量,一些采前措施值得特别注意[27]。包括选择抗病虫和果皮坚实的品种;清理和销毁果园内的烂果、烂枝;保持树冠通风、透光;对引起果实腐烂的病虫害和产展青霉素霉菌入侵点进行防控;使用杀菌剂防止采收期间和采收后霉菌的发生和生长;施用钙肥和磷肥,改善果实细胞结构,降低对果实腐烂的敏感性;不将矿质元素含量少的果实用于长期贮藏(超过3—4个月);果实充分成熟后采摘;采收、运输和装卸过程中避免对果实造成机械损伤;淘汰落地果、有病害的果和有机械损伤的果。苹果贮藏库应清洁卫生,可采取清洁剂和高压热水清洗后,喷洒0.025%次氯酸钠溶液消毒[27]。苹果贮藏期间,尽可能降低库温和 O2水平[118]。苹果装入聚乙烯包装袋后贮藏,可避免使用化学药剂,易于控制扩展青霉生长和展青霉素产生,与不装袋相比,展青霉素产生量至少可降低99.5%[119]。气调贮藏能很好地控制苹果上扩展青霉生长和展青霉素产生,在低或超低 O2和 CO2条件下,1℃气调贮藏 2—2.5个月的金冠苹果,均未检测到展青霉素[120]。冷藏后再在室温下贮藏,苹果上扩展青霉的生长会被重新激活[87],因此,苹果在冷藏结束后应尽快消费或加工。加工前贮藏是控制加工用苹果展青霉素积累的一个关键点。苹果加工前,最好在10℃以下冷藏[121];尽可能缩短室温贮藏时间,或不进行室温贮藏,如室温贮藏,时间不能超过48 h[122]。在苹果加工过程中,选果、清洗和整理是除去苹果中展青霉素最关键的步骤[27,123-124]。选果就是剔除腐烂严重的果实,苹果加工前应进行选果[56]。清洗,特别是高压水冲洗,是控制展青霉素污染的好办法,能清除果实的腐烂部分和高达54%的展青霉素[123]。苹果中展青霉素污染主要集中在肉眼看得见的腐烂部位,去除腐烂部位能显著减少展青霉素污染[125]。鉴于展青霉素能渗透到腐烂部位附近1—2 cm左右的健康组织中[126-127],将腐烂部位周围2 cm内的健康组织一并去除,通常可以避免展青霉素污染[127-128]。清除腐烂和受损的果实或清理掉霉烂的部分,能显著降低苹果制品中的展青霉素水平[42]。

水果加工过程中一些加工工艺对展青霉素有消减作用。辐照能使苹果汁中的展青霉素发生降解,用2.5 kGy的剂量辐照展青霉素起始浓度为2 mg·kg-1的苹果浓缩汁,可使展青霉素完全消失[129]。多波长紫外光照射也能使苹果汁中的展青霉素发生降解,其降解过程遵循一级时间动力学方程[124]。巴氏杀菌、酶处理、微孔过滤、蒸发等加工步骤能在一定程度上降低果品制品中的展青霉素水平[130]。巴氏杀菌能破坏扩展青霉的孢子[121],因而能降低随后扩展青霉产生展青霉素的风险。与超滤相比,采用回转式真空过滤的传统澄清方法去除展青霉素效果更好[123]。但超滤后用吸附树脂处理能显著降低苹果汁的展青霉素水平,并能改善苹果汁的色泽和澄清度[131]。展青霉素溶于水[32-33],用硫脲改性壳聚糖树脂(TMCR)能有效去除水溶液中的展青霉素,在pH 4.0和25℃条件下,24 h能吸附1.0 mg·g-1[132]。经丙硫醇功能化的介孔二氧化硅 SBA-15(SBA-15-PSH),其硫醇官能团能与展青霉素的共轭双键系统进行Michael加成反应,从而降低受污染苹果汁和水溶液中的展青霉素水平[133]。交联黄原酸化壳聚糖树脂(CXCR)是清除苹果汁中展青霉素的适宜吸附剂,其最适条件为pH 4和30℃下吸附18 h[134]。雪白丝衣霉(B. nivea)和黄褐丝衣菌(B. fulva)均为耐热菌,在层压纸板和聚对苯二甲酸乙二醇酯瓶包装的苹果清汁和浊汁中均能产生展青霉素,果汁生产企业应采取措施控制这两种真菌的子囊孢子[135]。高静水压(HHP)也可用于苹果饮料展青霉素污染控制[136]。

6 展青霉素的分析检测

薄层色谱法(TLC)是最早用于展青霉素检测的方法。由于样品前处理费时、杂质干扰严重、灵敏度低、只能半定量、与5-羟甲基糠醛等存在共萃取现象,该方法已甚少采用。目前,展青霉素检测主要采用LC-UV、LC-DAD、LC-MS/MS、GC、GC-MS、GC-MS/MS等气相/液相色谱法或气相/液相色谱质谱联用法,检出限一般在 ppb级[137-142],最低可至 0.09 ppb[143]。展青霉素是小分子量的极性化合物,有强紫外吸收,适于用配紫外检测器(UV)或二极管阵列检测器(DAD)的液相色谱仪(LC)检测,但存在 5-羟甲基糠醛和酚类物质干扰的问题[138-139]。展青霉素的LC-MS/MS检测通常采用大气压离子源(API源)的负离子源模式(如ESI源、APCI源和APPI源),采用 ESI源时会出现很强的基质效应,而采用 APCI源时基质效应可忽略[139]。采用 GC、GC-MS和GC-MS/MS检测展青霉素时,需进行分析前衍生化,费时、繁琐,而采用进样口衍生则可节约衍生试剂和样品制备时间[141]。除前述方法外,展青霉素检测还可采用胶束动电毛细管色谱法(MEKC),如MEKC-DAD(UV)、DLLME-MEKC-DAD等,检测限可低至不足1 ppb[144-146]。值得注意的是,在检测苹果浊汁展青霉素含量时,相比于浊汁的液相部分,浊汁的固体部分富含蛋白质,展青霉素极有可能与蛋白质相互作用而结合在一起,使高达20%的展青霉素未被检测到,从而导致毒性水平的低估[147]。

展青霉素检测中普遍采用液液萃取(LLE)或固相萃取(SPE)[140,144,148-150]。由于需使用更多的有机溶剂,LLE萃取成本高而且耗时,用碳酸钠净化还会使展青霉素发生降解(因为展青霉素在酸性介质中更稳定)[142]。与LLE萃取相比,SPE更简便,回收率高,污染小。采用SPE时,提取相中加入NaH2PO4有利于 pH保持微酸性,以免展青霉素降解[151]。基于分子印迹聚合物(MIPs)的 SPE,模板分子识别选择性和亲和力高[152],有良好的选择性和稳定性,更高效[153],已成功用于苹果汁中真菌毒素的检测[153-155]。分散液液微萃取(DLLME)提取时间短、操作简单、富集因子和回收率高,离子液体(IL)具有对空气和水分稳定,不挥发,热稳定性好,粘度可调,与水和有机溶剂混溶等优点,可作为 DLLME的提取溶剂[140]。在DLLME基础上,还发展出了二元溶剂分散液液微萃取(BS-DLLME)[150]。通常,传统固体、半固体和粘性生物样品的分析中,样品制备、提取和分离往往需要好几步,而基质固相分散(MSPD)可将所有这些步骤合并为一步完成[142]。除上述方法外,人们也对盐析旋涡辅助液液微萃取(salting out-VALLME)[156]、QuEChERS[138]、基于环糊精的聚合物[157]等进行了研究,效果良好。

与普遍采用的色谱方法和色谱质谱联用方法相比,免疫学方法具有方便、灵敏、可小型化、允许实时检测的特点[158]。自MCELROY和WEISS[159]制备出多克隆抗体,建立展青霉素检测的酶联免疫法(ELISA)以来,已开发出了表面等离子体共振免疫分析法、化学发光免疫分析法、近红外荧光免疫分析法、石英晶体微天平(QCM)免疫分析法、荧光免疫分析法等多种测定展青霉素的免疫学方法[158,160-161]。然而,免疫学方法使用的免疫抗体由动物产生,昂贵且不可再生,为提高检测性能,展青霉素免疫学检测可改用合成的生物受体,如寡核苷酸适配体[158]。与抗体相比,寡核苷酸适配体亲和力高、稳定、可与多种目标物结合、合成简单[162-163]。用 DNA适配体PAT-11建立的基于酶-发色底物系统的展青霉素检测方法,线性范围在0.05—2.5 μg·L-1,检出限低至0.048 μg·L-1[158]。展青霉素的近红外荧光免疫分析法也很灵敏,检出限可低至0.06 μg·L-1[161]。此外,还有基于分子印迹溶胶-凝胶聚合物的石英晶体微天平(MIP-QCM)传感器展青霉素检测技术[164]。

展青霉素是一种相当稳定的化合物,无可靠的方法加以清除,而利用快速、专一的方法对潜在的展青霉素产毒真菌进行早期检测,可以在展青霉素达到不可接受的水平前,甚至是展青霉素合成前,阻止其进入食物链[165]。PCR是检测食品中产展青霉素真菌的有效方法[166],针对真菌毒素生物合成或调控通路中的目标基因开发探针[167-170],扩展青霉DNA检测限可低至ng·mg-1级[165,171],建立的(多重)实时PCR方法可同时检测多种,甚至数十种产展青霉素真菌[172-173]。ELISA也可用于真菌鉴别[37],用常见的食源性真菌橘灰青霉(P. aurantiogriseum)制备的抗原可与测试的45种青霉属真菌中的43种反应[174]。

7 展望

果树种类和品种多,地域分布广,对展青霉素产毒真菌的敏感性存在差异。开展果树抗展青霉素产毒真菌鉴定,筛选抗性品种和抗性种质资源,可为抗性品种的培育和推广创造有利条件。许多真菌都能产生展青霉素,但不同真菌之间以及同一种真菌不同菌株之间产毒能力有异。有必要针对主要果品及其主产区,开展展青霉素产毒真菌收集、分离和鉴定评价研究,建立展青霉素产毒真菌资源库,明确展青霉素优势产毒菌株及其区域分布,并以其为对象,有针对性地进行展青霉素污染防控研究。现已明确展青霉素生物合成通路约由10步构成,棒曲霉和扩展青霉的展青霉素生物合成基因簇均包含相同的15个基因。如能针对展青霉素生物合成通路中的关键步骤、关键酶和关键基因展开研究,提出阻遏展青霉素生物合成的技术和产品,必将为展青霉素污染防控开辟更广阔的前景。果品及其制品一旦被展青霉素污染就很难彻底清除,因此,预防和控制产毒真菌侵染是展青霉素污染防控的关键,除栽培抗病品种和加强田间管理外,化学防控和生物防控是重要技术手段。为应对展青霉素产毒真菌抗药性发展,应持续从新研发的药剂中筛选高效、低毒的低风险杀菌剂。使用微生物拮抗剂是水果采后病害防控最有前途的杀菌剂替代方案。有鉴于此,应高度重视生物拮抗剂,特别是拮抗菌的发掘与利用,包括单独使用和与低风险杀菌剂、贮藏技术等的结合使用。开发和利用对展青霉素产毒真菌有很好抑制作用的植物源性成分也属生物防控范畴,已多有报道。对于果品制品的展青霉素污染防控,就加工环节而言,主要是展青霉素污染脱除与消减技术和产品的研究。关于展青霉素检测技术,今后的发展方向是快速、高效、经济、环保,特别是提取、净化技术和产品、现场检测技术以及与其他毒素和污染物的同时检测技术的研发。此外,展青霉素产毒真菌的早期检测技术也是一个值得关注的领域。展青霉素污染主要发生在腐烂、变质的果实和果品制品中,目前虽有不少关于果品及其制品展青霉素污染的报道,但关于展青霉素污染风险评估的报道尚不多见,今后这方面的研究应予以加强,特别是中国这样一个果品生产、消费和加工大国。

[1]CAST. Mycotoxins: Risks in plant, animal, and human systems. Ames,Iowa: Council for Agricultural Science and Technology, 2003: 1-199.

[2]PUEL O, GALTIER P, OSWALD I P. Biosynthesis and toxicological effects of patulin. Toxins, 2010, 2: 613-631.

[3]CIEGLER A, DETROY R W, LILLEHOJ E B. Patulin, penicillic acid,and other carcinogenic lactones//CIEGLER A, KADIS S, AJL S J.Microbial Toxins, Vol 6. New York and London: Academic Press,1971: 409-434.

[4]CIEGLER A. Patulin//RODRICKS J V, HESSELTINE C W, MEHLMAN M A. Mycotoxins in Human and Animal Health. Park Forest South,Illinois: Pathotox Publishers, Inc., 1977: 609-624.

[5]BENNETT J B, KLICH M. Mycotoxins. Clinical Microbiology Reviews, 2003, 16(3): 497-516.

[6]GUO C, YUE T, YUAN Y, WANG Z, GUO Y, WANG L, LI Z.Biosorption of patulin from apple juice by caustic treated waste cider yeast biomass. Food Control, 2013, 32: 99-104.

[7]CHERAGHALI A M, MOHAMMADI H R, AMIRAHMADI M,YAZDANPANAH H, ABOUHOSSAIN G, ZAMANIAN F,KHANSARI M G, AFSHAR M. Incidence of patulin contamination in apple juice produced in Iran. Food Control, 2005, 16: 165-167.

[8]ZOUAOUI N, SBAII N, BACHA H, ABID-ESSEFI S. Occurrence of patulin in various fruit juice marketed in Tunisia. Food Control, 2015,51: 356-360.

[9]SHEPHARD G S, VAN DER WESTHUIZEN L, KATERERE D R,HERBST M, PINEIRO M. Preliminary exposure assessment of deoxynivalenol and patulin in South Africa. Mycotoxin Research,2010, 26: 181-185.

[10]ABRAMSON D, LOMBAERT CLEAR G R M, SHOLBERG P,TRELKA R, ROSIN E. Production of patulin and citrinin by Penicillium expansum from British Columbia (Canada) apples.Mycotoxin Research, 2009, 25: 85-88.

[11]CUNHA S C, FARIA M A, FERNANDES J O. Determination of patulin in apple and quince products by GC-MS using13C5-7patulin as internal standard. Food Chemistry, 2009, 115: 352-359.

[12]VACLAVIKOVA M, DZUMAN Z, LACINA O, FENCLOVA M,VEPRIKOVA Z, ZACHARIASOVA M, HAJSLOVA J. Monitoring survey of patulin in a variety of fruit-based products using a sensitive UHPLC-MS/MS analytical procedure. Food Control, 2015, 47:577-584.

[13]SARUBBI F, FORMISANO G, AURIEMMA G, ARRICHIELLO A,PALOMBA R. Patulin in homogenized fruit’s and tomato products.Food Control, 2016, 59: 420-423.

[14]CUNHA S C, FARIA M A, PEREIRA V L, OLIVEIRA T M, LIMA A C, PINTO E. Patulin assessment and fungi identification in organic and conventional fruits and derived products. Food Control, 2014, 44:185-190.

[15]REDDY K R N, SPADARO D, LORE A, GULLINO M L,GARIBALDI A. Potential of patulin production by Penicillium expansum strains on various fruits. Mycotoxin Research, 2010, 26:257-265.

[16]MARÍN S, MATEO E M, SANCHIS V, VALLE-ALGARRA F M,RAMOS A J, JIMÉNEZ M. Patulin contamination in fruit derivatives,including baby food, from the Spanish market. Food Chemistry, 2011,124: 563-568.

[17]GUO Y, ZHOU Z, YUAN Y, YUE T. Survey of patulin in apple juice concentrates in Shaanxi (China) and its dietary intake. Food Control,2013, 34: 570-573.

[18]PIQUÉ E, VARGAS-MURGA L, GÓMEZ-CATALÁN J, DE LAPUENTE J, MARIA LLOBET J. Occurrence of patulin in organic and conventional apple-based food marketed in Catalonia and exposure assessment. Food and Chemical Toxicology, 2013, 60:199-204.

[19]MURILLO-ARBIZU M, GONZÁLEZ-PEÑAS E, AMÉZQUETA S.Comparison between capillary electrophoresis and high performance liquid chromatography for the study of the occurrence of patulin in apple juice intended for infants. Food and Chemical Toxicology, 2010,48: 2429-2434.

[20]EKINCI R, OTAĞ M, KADAKAL Ç. Patulin & ergosterol: Newquality parameters together with aflatoxins in hazelnuts. Food Chemistry, 2014, 150: 17-21.

[21]KARACA H, NAS S. Aflatoxins, patulin and ergosterol contents of dried figs in Turkey. Food Additives & Contaminants, 2006, 23 (5):502-508.

[22]KATAOKA H, ITANO M, ISHIZAKI A, SAITO K. Determination of patulin in fruit juice and dried fruit samples by in-tube solid-phase microextraction coupled with liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry. Journal of Chromatography A, 2009, 1216: 3746-3750.

[23]BARREIRA M J, ALVITO P C, ALMEIDA C M M. Occurrence of patulin in apple-based-foods in Portugal. Food Chemistry, 2010, 121:653-658.

[24]CHO M K, KIM K, SEO E, KASSIM N, MTENGA A B, SHIM W B,LEE S H, CHUNG D W. Occurrence of patulin in various fruit juices from South Korea: An exposure assessment. Food Science and Biotechnology, 2010, 19 (1): 1-5.

[25]LEE T P, SAKAI R, MANAF N A, RODHI A M, SAAD B. High performance liquid chromatography method for the determination of patulin and 5-hydroxymethylfurfural in fruit juices marketed in Malaysia. Food Control, 2014, 38: 142-149.

[26]SALAS M P, REYNOSO C M, CÉLIZ G, DAZ M, RESNIK S L.Efficacy of flavanones obtained from citrus residues to prevent patulin contamination. Food Research International, 2012, 48: 930-934.

[27]SANT’ANA A D S, ROSENTHAL A, DE MASSAGUER P R. The fate of patulin in apple juice processing: A review. Food Research International, 2008, 41: 441-453.

[28]MOAKE M M, PADILLA-ZAKOUR O I, WOROBO R W.Comprehensive review of patulin control methods in foods.Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety, 2005, 1:8-21.

[29]SPADARO D, LORÈ A, GARIBALDI A, GULLINO M L. A new strain of Metschnikowia fructicola for postharvest control of Penicillium expansum and patulin accumulation on four cultivars of apple. Postharvest Biology and Technology, 2013, 75: 1-8.

[30]ZAIED C, ABID S, HLEL W, BACHA H. Occurrence of patulin in apple-based-foods largely consumed in Tunisia. Food Control, 2013,31: 263-267.

[31]MAJERUS P, HAIN J, KÖLB C. Patulin in grape must and new, still fermenting wine (Federweißer). Mycotoxin Research, 2008, 24:135-139.

[32]宗元元, 李博强, 秦国政, 张占全, 田世平. 棒曲霉素对果品质量安全的危害及其研究进展. 中国农业科技导报, 2013, 15(4) : 36-41.ZONG Y Y, LI B Q, QIN G Z, ZHANG Z Q, TIAN S P. Toxicity of patulin on fruit quality and its research progress. Journal of Agricultural Science and Technology, 2013, 15(4): 36-41. (in Chinese)

[33]王娅芳, 刘利亚, 黄培林. 展青霉素检测方法及污染情况的研究进展. 现代预防医学, 2012, 39(19): 5116-5118, 5123.WANG Y F, LIU L Y, HUANG L. Research advances on determination and pollution of patulin. Modern Preventive Medicine,2012, 39(19): 5116-5118, 5123. (in Chinese)

[34]MCCORMICK S. Microbial detoxification of mycotoxins. Journal of Chemical Ecology, 2013, 39: 907-918.

[35]TANNOUS J, EL KHOURY R, SNINI S P, LIPPI Y, EL KHOURY A, ATOUI A, LTEIF R, OSWALD I P, PUEL O. Sequencing,physical organization and kinetic expression of the patulin biosynthetic gene cluster from Penicillium expansum. International Journal of Food Microbiology, 2014, 189: 51-60.

[36]WRIGHT S A. Patulin in food. Current Opinion in Food Science,2015, 5: 105-109.

[37]PITT J I, HOCKING A D. Fungi and Food Spoilage (3rdEdition).New York: Springer Sciencet +Business Media, 2009.

[38]SCHEBB N H, FABER H, MAUL R, HEUS F, KOOL J, IRTH H,KARST U. Analysis of glutathione adducts of patulin by means of liquid chromatography (HPLC) with biochemical detection (BCD)and electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry (ESI-MS/MS).Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry, 2009, 394: 1361-1373.

[39]JECFA. Evaluations of Certain Food Additives and Contaminants.WHO Technical Report Series, No. 859. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 1995.

[40]HAWAR S, VEVERS W, KARIEB S, ALI B K, BILLINGTON R,BEAL J. Biotransformation of patulin to hydroascladiol by Lactobacillus plantarum. Food Control, 2013, 34: 502-508.

[41]SANZANI S M, DE GIROLAMO A, SCHENA L, SOLFRIZZO M,IPPOLITO A, VISCONTI A. Control of Penicillium expansum and patulin accumulation on apples by quercetin and umbelliferone.European Food Research Technology, 2009, 228: 381-389.

[42]SPADARO D, CIAVORELLA A, FRATI S, GARIBALDI A,GULLINO M L. Incidence and level of patulin contamination in pure and mixed apple juices marketed in Italy. Food Control, 2007, 18:1098-1102.

[43]CODEX ALIMENTARIUS COMMISSION. General Standard for Contaminants and Toxins in Food and Feed (CODEX STAN 193-1995) [S].

[44]EUROPEAN COMMISSION. Regulation (EC) No 1881/2006 of 19 December 2006 setting maximum levels for certain contaminants infoodstuffs. Of fi cial Journal of the European Union, L 364/5.

[45]聂继云. 农产品质量与安全·果品卷. 北京: 中国农业科学技术出版社, 2017: 153.NIE J Y. Quality and Safety of Agriculture Product: Fruits. Beijing:China Agricultural Science and Technology Press, 2017: 153. (in Chinese)

[46]ALVES I, OLIVEIRA N G, LAIRES A, RODRIGUES A S, RUEFF J.Induction of micronuclei and chromosomal aberrations by the mycotoxin patulin in mammalian cells: Role of ascorbic acid as a modulator of patulin clastogenicity. Mutagenesis, 2000, 15(3):229-234.

[47]INTERNATIONAL AGENCY FOR RESEARCH ON CANCER.IARC Monographs on The Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans (Vol. 82): Some Traditional Herbal Medicines, Some Mycotoxins, Naphthalene and Styrene. Lyon: IARC Press, 2002.

[48]CAO J, ZHANG H, YANG Q, REN R. Efficacy of Pichia caribbica in controlling blue mold rot and patulin degradation in apples.International Journal of Food Microbiology, 2013, 162: 167-173.

[49]NORSTADT F A, MCCALLA T M. Phytotoxic substance from a species of Penicillium. Science, 1963, 140: 410-411.

[50]ELLIS J R, MCCALLA T M. Effects of patulin and method of application on growth stages of wheat. Applied Microbiology, 1973,25: 562-566.

[51]IWAHASHI Y, HOSODA H, PARK J H, LEE J H, SUZUKI Y,KITAGAWA E, MURATA S M, JWA N S, GU M B, IWAHASHI H.Mechanisms of patulin toxicity under conditions that inhibit yeast growth. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 2006, 54:1936-1942.

[52]BARAD S, SIONOV E, PRUSKY D. Role of patulin in post-harvest diseases. Fungal Biology Reviews, 2016, 30: 24-32.

[53]孔华忠. 中国真菌志(第 35卷),青霉属及其相关有性型属. 北京:科学出版社, 2007: 图版I-XV.KONG H Z. Flora Fungorum Sinicorum (Vol. 35): Penicillium Et Telecomorphi Cognati. Beijing: Science Press, 2007: Plate I-XV. (in Chinese)

[54]MORALES H, SANCHIS V, COROMINES J, RAMOS A J, MARÍN S. Inoculum size and intraspecific interactions affects Penicillium expansum growth and patulin accumulation in apples. Food Microbiology, 2008, 25: 378-385.

[55]CHEN L, INGHAM B H, INGHAM S C. Survival of Penicillium expansum and patulin production on stored apples after wash treatments. Journal of Food Science, 2004, 69(8): C669-C675.

[56]BAERT K, DEVLIEGHERE F, AMIRI A, DE MEULENAER B.Evaluation of strategies for reducing patulin contamination of apple juice using a farm to fork risk assessment model. International Journal of Food Microbiology, 2012, 154: 119-129.

[57]NERI F, DONATI I, VERONESI F, MAZZONI D, MARI M.Evaluation of Penicillium expansum isolates for aggressiveness,growth and patulin accumulation in usual and less common fruit hosts.International Journal of Food Microbiology, 2010, 143: 109-117.

[58]ANDERSEN B, SMEDSGAARD J, FRISVAD J C. Penicillium expansum: Consistent production of patulin, chaetoglobosins, and other secondary metabolites in culture and their natural occurrence in fruit products. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 2004, 52:2421-2428

[59]SPEIJERS G J A. Patulin//MAGAN N, OLSEN M. Mycotoxins in Foods: Detection and Control. Boca Raton: CRC Press, 2004:339-352.

[60]VISAGIE C M. Biodiversity in the genus Penicillium from coastal Fynbos soil [D]. Stellenbosch: Stellenbosch University Press, 2008.

[61]KARABULUT O A, BAYKAL N. Evaluation of the use of microwave power for the control of postharvest diseases of peaches.Postharvest Biology and Technology, 2002, 26: 237-240.

[62]VERO S, MONDINO P, BURGUENO J, SOUBES M,WISNIEWSKI M. Characterization of biocontrol activity of two yeast strains from Uruguay against blue mold of apple. Postharvest Biology and Technology, 2002, 26: 91-98.

[63]SOMMER N F, FORTLAGE R J, EDWARDS D C. Postharvest diseases of selected commodities//KADER A A. Postharvest Technology of Horticultural Crops (2ndEdition). Oakland, California: University of California, Division of Agriculture and Natural Resources, 1992.

[64]BALLESTER A R, MARCET-HOUBEN M, LEVIN E, SELA N,SELMA-LAZARO C, CARMONA L, WISNIEWSKI M, DROBY S,GONZALEZ-CANDELAS L, GABALDON T. Genome,transcriptome, and functional analyses of Penicillium expansum provide new insights into secondary metabolism and pathogenicity.Molecular Plant-Microbe Interactions, 2015, 28 (3): 232-248.

[65]ELHARIRY H, BAHOBIAL A A, GHERBAWY Y. Genotypic identification of Penicillium expansum and the role of processing on patulin presence in juice. Food and Chemical Toxicology, 2011, 49:941-946.

[66]王文辉, 徐步前. 果品采后处理及贮运保鲜. 北京: 金盾出版社,2003: 60-76.WANG W H, XU B Q. Postharvest Treatment, Storage, Transportation,and preservation of Fruits. Beijing: Jindun Publishing House, 2003:60-76. (in Chinese)

[67]MARI M, NERI F, BERTOLINI P. Management of important diseases in Mediterranean high value crops. Stewart Postharvest Review, 2009, 5(2): 49-60.

[68]LI B Q, ZONG, Y Y, DU Z L, CHEN Y, ZHANG Z Q, QIN G Z,ZHAO W M, TIAN S P. Genomic characterization reveals insights into patulin biosynthesis and pathogenicity in Penicillium species.Molecular Plant-Microbe Interactions, 2015, 28 (6): 635-647.

[69]SNINI S P, TADRIST S, LAFFITTE J, JAMIN E L, OSWALD I P,PUEL O. The gene PatG involved in the biosynthesis pathway of patulin, a food-borne mycotoxin, encodes a 6-methylsalicylic acid decarboxylase. International Journal of Food Microbiology, 2014,171: 77-83.

[70]GLASER N, STOPPER H. Patulin: Mechanism of genotoxicity. Food and Chemical Toxicology, 2012, 50: 1796-1801.

[71]PFEIFFER E, GROSS K, METZLER M. Aneuploidogenic and clastogenic potential of the mycotoxins citrinin and patulin.Carcinogenesis, 1998, 19 (7): 1313-1318.

[72]SCHUMACHER D M, MUELLER C, METZLER M, LEHMANN L.DNA-DNA cross-links contribute to the mutagenic potential of the mycotoxin patulin.Toxicology Letters, 2006, 166: 268-275.

[73]LEE K S, ROSCHENTHALER R J. DNA-damaging activity of patulin in Escherichia coli. Applied and Environmental Microbiology,1986, 52(5): 1046-1054.

[74]SCHUMACHER D M, METZLER M, LEHMANN L. Mutagenicity of the mycotoxin patulin in cultured Chinese hamster V79 cells, and its modulation by intracellular glutathione. Archives of Toxicology,2005, 79: 110-121.

[75]AYED-BOUSSEMA I, ABASSI H, BOUAZIZ C, HLIMA W B,AYED Y, BACHA H. Antioxidative and antigenotoxic effect of vitamin E against patulin cytotoxicity and genotoxicity in HepG2 cells.Environmental Toxicology, 2013, 28: 299-306.

[76]PFEIFFER E, DIWALD T T, METZLER M. Patulin reduces glutathione elevel and enzyme activities in rat liver slices. Molecular Nutrition & Food Research, 2005, 49: 329-336.

[77]INTERNATIONAL AGENCY FOR RESEARCH ON CANCER.IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of the Carcinogenic Risk of Chemicals to Humans (Vol. 40): Some Naturally Occurring and Synthetic Food Components, Furocoumarins and Ultraviolet Radiation. Lyon: IARC Press, 1986: 83-98.

[78]BARHOUMI R, BURGHARDT R C. Kinetic analysis of the chronology of patulin- and gossypol-induced cytotoxicity in vitro.Fundamental Applied Toxicology, 1996, 30: 290-297.

[79]RILEY R T, SHOWKER J L. The mechanism of patulin’s cytotoxicity and the antioxidant activity of indole tetramic acids.Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology, 1991, 109: 108-126.

[80]MAHFOUD R, MARESCA M, GARMY N, FANTINI J. The mycotoxin patulin alters the barrier function of the intestinal epithelium: Mechanism of action of the toxin and protective effects of glutathione. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology, 2002, 181:209-218.

[81]THUST R, KNEIST S, MENDEL J. Patulin, a further clastogenic mycotoxin, is negative in the SCE assay in Chinese hamster V79-E cells in vitro. Mutation Research, 1982, 103: 91-97.

[82]FLIEGE R, METZLER M. Electrophilic properties of patulin. Adduct structures and reaction pathways with 4-bromothiophenol and other model nucleophiles. Chemical Research in Toxicology, 2000, 13:363-372.

[83]ZHOU S M, JIANG L P, GENG C Y, CAO J, ZHONG L F.Patulin-induced genotoxicity and modulation of glutathione in HepG2 cells. Toxicon, 2009, 53: 584-586.

[84]JANISIEWICZ W J, KORSTEN L. Biological control of postharvest diseases of fruits. Annual Review of Phytopathology, 2002, 40:411-441.

[85]ECKERT J W, OGAWA J M. Recent developments in the chemical control of postharvest diseases. Acta Horticulturae, 1990, 269:477-494.

[86]ZHOU T, NORTHOVER J, SCHNEIDER K E, LU X W. Interactions between Pseudomonas syringae MA-4 and cyprodinil in the control of blue mold and gray mold of apples. Canadian Journal of Plant Pathology, 2002, 24 (2):154-161.

[87]MORALES H, MARÍN S, RAMOS A J, SANCHIS V. Influence of post-harvest technologies applied during cold storage of apples in Penicillium expansum growth and patulin accumulation: A review.Food Control, 2010, 21: 953-962.

[88]ERRAMPALLI D, CRNKO N. Control of blue mold caused by Penicillium expansum on apples “Empire” with fludioxonil and cyprodinil. Canadian Journal of Plant Pathology, 2004, 26 (1): 70-75.[89]ERRAMPALLI D, BRUBACHER N R, DEELL J R. Sensitivity of Penicillium expansum to diphenylamine and thiabendazole and postharvest control of blue mold with fludioxonil in ‛McIntosh’ apples.Postharvest Biology and Technology, 2006, 39: 101-107.

[90]MORALES H, SANCHIS V, USALL J, RAMOS A J, MARÍN S.Effect of biocontrol agents Candida sake and Pantoea agglomerans on Penicillium expansum growth and patulin accumulation in apples.International Journal of Food Microbiology, 2008, 122: 61-67.

[91]SHOLBERG P L, HARLTON C, HAAG P, LÉVESQUE C A,ÓGORMAN D, SEIFERT K. Benzimidazole and diphenylamine sensitivity and identity of Penicillium spp. that cause postharvest blue mold of apples using β-tubulin gene sequences. Postharvest Biology and Technology, 2005, 36: 41-49.

[92]MORALES H, MARÍN S, OBEA L, PATINO B, DOMENECH M,RAMOS A J, SANCHIS V. Ecophysiological caracterization of Penicillium expansum population in Lleida (Spain). International Journal of Food Microbiology, 2008, 122: 243-252.

[93]CABANAS R, ABARCA M L, BRUGULAT M R, CABANES F J.Comparison of methods to detect resistance of Penicillium expansum to thiabendazole. Letters in Applied Microbiology, 2009, 48: 241-246.

[94]ERRAMPALLI D, NORTHOVER J, SKOG L, BRUBACHER N R,COLLUCCI C A. Control of blue mold (Penicillium expansum) by fludioxonil in apples (cv Empire) under controlled atmosphere and cold storage conditions. Pest Management Science, 2005, 61:591-596.

[95]BARALDI E, MARI M, CHIERICI E, PONDRELLI M, BERTOLINI P, PRATELLA G C. Studies on thiabendazole resistance of Penicillium expansum of pears: Pathogenic fitness and genetic characterization. Plant Pathology, 2003, 52: 362-370.

[96]PATERSON R R M. Some fungicides and growth inhibitor/biocontrolenhancer 2-deoxy-D-glucose increase patulin from Penicillium expansum strains in vitro. Crop Protection, 2007, 26: 543-548.

[97]HASAN H A H. Patulin and aflatoxin in brown rot lesion of apple fruits and their regulation. World Journal of Microbiology &Biotechnology, 2000, 16: 607-612.

[98]DROBY S, WISNIEWSKI M, MACARISIN D, WILSON C. Twenty years of postharvest biocontrol research: Is it time for a new paradigm?Postharvest Biology and Technology, 2009, 52: 137-145.

[99]ETEBARIAN H R, SHOLBERG P L, EASTWELL K C, SAYLER R J. Biological control of apple blue mold with Pseudomonas fluorescens. Canadian Journal of Microbiology, 2005, 51: 591-598.

[100]USALL J, TEIXIDÓ N, TORRES R, OCHOA DE ERIBE X, VIÑAS I. Pilot tests of Candida sake (CPA-1) applications to control postharvest blue mold on apple fruit. Postharvest Biology and Technology, 2001, 21: 147-156.

[101]FAN Q, TIAN S P. Postharvest biological control of grey mold and blue mold on apple by Cryptococcus albidus (Saito) Skinner.Postharvest Biology and Technology, 2001, 21: 341-350.

[102]TOLAINI V, ZJALIC S, REVERBERI M, FANELLI C, FABBRI A A, DEL FIORE A, DE ROSSI P, RICELLI A. Lentinula edodes enhances the biocontrol activity of Cryptococcus laurentii against Penicillium expansum contamination and patulin production in apple fruits. International Journal of Food Microbiology, 2010, 138:243-249.

[103]TRIAS R, BAÑERAS L, MONTESINOS E, BADOSA E. Lactic acid bacteria from fresh fruit and vegetables as biocontrol agents of phytopathogenic bacteria and fungi. International Microbiology, 2008,11: 231-236.

[104]CALVO J, CALVENTE V, ORELLANO M E, BENUZZI D,TOSETTI M I S. Biological control of postharvest spoilage caused by Penicillium expansum and Botrytis cinerea in apple by using the bacterium Rahnella aquatilis. International Journal of Food Microbiology, 2007, 113: 251-257.

[105]LI R P, ZHANG H Y, LIU W M, ZHENG X D. Biocontrol of postharvest gray and blue mold decay of apples with Rhodotorula mucilaginosa and possible mechanisms of action. International Journal of Food Microbiology, 2011, 146: 151-156.

[106]LIMA G, CASTORIA R, DE CURTIS F, RAIOLA A, RITIENI A,DE CICCO V. Integrated control of blue mould using new fungicides and biocontrol yeasts lowers levels of fungicide residues and patulin contamination in apples. Postharvest Biology and Technology, 2011,60: 164-172.

[107]MOSS M O, LONG M T. Fate of patulin in the presence of the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Food Additives and Contaminants, 2002,19(4): 387-399.

[108]RICELLI A, BARUZZI F, SOLFRIZZO M, MOREA M, FANIZZI F P. Biotransformation of patulin by Gluconobacter oxydans. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2007, 73: 785-792.

[109]CASTORIA R, MANNINA L, DURÁN-PATRΌN R, MAFFEI F,SOBOLEV A P, DE FELICE D V, PINEDO-RIVILLA C, RITIENI A,FERRACANE R, WRIGHT S A I. Conversion of the mycotoxin patulin to the less toxic desoxypatulinic acid by the biocontrol yeast Rhodosporidium kratochvilovae strain LS11. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 2011, 59: 11571-11578.

[110]ZHANG X, GUO Y, MA Y, CHAI Y, LI Y. Biodegradation of patulin by a Byssochlamys nivea strain. Food Control, 2016, 64: 142-150.

[111]FUCHS S, SONTAG G, STIDL R, EHRLICH V, KUNDI M,KNASMÜLLER S. Detoxification of patulin and ochratoxin A, two abundant mycotoxins, by lactic acid bacteria. Food and Chemical Toxicology, 2008, 46: 1398-1407.

[112]COELHO A R, CELLI M G, ONO E Y S, WOSIACKI G,HOFFMANN F L, PAGNOCCA F C, HIROOKA E Y. Penicillium expansum versus antagonist yeasts and patulin degradation in vitro.Brazilian Archives of Biology and Technology, 2007, 50 (4): 725-733.

[113]CASTORIA R, MORENA V, CAPUTO L, PANFILI G, DE CURTISF, DE CICCO V. Effect of the biocontrol yeast Rhodotorula glutinis strain LS11 on patulin accumulation in stored apples. Phytopathology,2005, 95(11): 1271-1278.

[114]GUO C, YUE T, YUAN Y, WANG Z, GUO Y, WANG L, LI Z.Biosorption of patulin from apple juice by caustic treated waste cider yeast biomass. Food Control, 2013, 32: 99-104.

[115]ZHU R, FEUSSNER K, WU T, YAN F, KARLOVSKY P, ZHENG X.Detoxification of mycotoxin patulin by the yeast Rhodosporidium paludigenum. Food Chemistry, 2015, 179: 1-5.

[116]TOPCU A, BULAT T, WISHAH R, BOYACI I H. Detoxification of aflatoxin B1 and patulin by Enterococcus faecium strains.International Journal of Food Microbiology, 2010, 139: 202-205.

[117]SANZANI S M, SCHENA L, NIGRO F, DE GIROLAMO A,IPPOLITO A. Effect of quercetin and umbelliferone on the transcript level of Penicillium expansum genes involved in patulin biosynthesis.European Journal of Plant Pathology, 2009, 125: 223-233.

[118]BAERT K, DEVLIEGHERE F, FLYPS H, OOSTERLINCK M,AHMED M M, RAJKOVIĆ A, VERLINDEN B, NICOLAÏ B,DEBEVERE J, DE MEULENAER B. Influence of storage conditions of apples on growth and patulin production by Penicillium expansum.International Journal of Food Microbiology, 2007, 119: 170-181.

[119]MOODLEY R S, GOVIDEN R, ODHAV B. The effect of modified atmospheres and packaging on patulin production in apples. Journal of Food Protection, 2002, 65(5): 867-871.

[120]MORALES H, SANCHIS V, ROVIRA A, RAMOS A J, MARÍN S.Patulin accumulation in apples during postharvest: Effect of controlled atmosphere storage and fungicide treatments. Food Control, 2007, 18:1443-1448.

[121]FAO/IAEA TRAINING AND REFERENCE CENTER FOR FOOD AND PESTICIDE CONTROL. FAO Food and Nutrition Paper 73:Manual on the Application of the HACCP System in Mycotoxin Prevention and Control. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 2001.

[122]MORALES H, MARÍN S, CENTELLES X, RAMOS A J, SANCHIS V. Cold and ambient deck storage prior to processing as a critical control point for patulin accumulation. International Journal of Food Microbiology, 2007, 116: 260-265.

[123]ACAR J, GÖKMEN V, TAYDAS E E. The effects of processing technology on the patulin content of juice during commercial apple juice concentrate production. Z Lebensm Unters Forsch A, 1998, 207:328-331.

[124]IBARZ R, GARVÍN A, FALGUERA V, PAGÁN J, GARZA S,IBARZ A. Modelling of patulin photo-degradation by a UV multi-wavelength emitting lamp. Food Research International, 2014,66: 158-166.

[125]BANDOH S, TAKEUCHI M, OHSAWA K, HIGASHIHARA K,KAWAMOTO Y, GOTOA T. Patulin distribution in decayed apple and its reduction. International Biodeterioration & Biodegradation,2009, 63: 379-382.

[126]TANIWAKI M H, HOENDERBOOM C J M, VITALI A A, EIROA M N U. Migration of patulin in apples. Journal of Food Protection,1992, 55 (11): 902-904.

[127]JANOTOVÁ L, ČÍŽZKOVÁ H, PIVOŇKA J, VOLDŘICH M. Effect of processing of apple puree on patulin content. Food Control, 2011,22: 977-981.

[128]RYCHLIK M, SCHIEBERLE P. Model studies on the diffusion behavior of the mycotoxin patulin in apples, tomatoes, and wheat bread. European Food Research Technology, 2001, 212(3): 274-278.

[129]ŻEGOTA H, ŻEGOTA A, BACHMAN S. Effect of irradiation on the patulin content and chemical composition of apple juice concentrate. Z Lebensm Unters Forsch, 1988, 187: 235-238.

[130]WELKE J E, HOELTZ M, DOTTORI H A, NOLL I B. Effect of processing stages of apple juice concentrate on patulin levels. Food Control, 2009, 20: 48-52.

[131]GÖKMEN V, ARTIK N, ACAR J, KAHRAMAN N, POYRAZOĞLU E.Effects of various clarification treatments on patulin, phenolic compound and organic acid compositions of apple juice. European Food Research and Technology, 2001, 213: 194-199.

[132]LIU B, PENG X, CHEN W, LI Y, MENG X, WANG D, YU G.Adsorptive removal of patulin from aqueous solution using thiourea modified chitosan resin. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 2015, 80: 520-528.

[133]APPELL M, JACKSON M A, DOMBRINK-KURTZMAN M A.Removal of patulin from aqueous solutions by propylthiol functionalized SBA-15. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 2011, 187:150-156.

[134]PENG X, LIU B, CHEN W, LI X, WANG Q, MENG X, WANG D.Effective biosorption of patulin from apple juice by cross-linked xanthated chitosan resin. Food Control, 2016, 63: 140-146.

[135]SANT'ANA A S, SIMAS R C, ALMEIDA C A A, CABRAL E C,RAUBER R H, MALLMANN C A, EBERLIN M N, ROSENTHAL A, MASSAGUER P R. Influence of package, type of apple juice and temperature on the production of patulin by Byssochlamys nivea and Byssochlamys fulva. International Journal of Food Microbiology,2010, 142: 156-163.

[136]HAO H, ZHOU T, KOUTCHMA T, WU F, WARRINER K. Highhydrostatic pressure assisted degradation of patulin in fruit and vegetable juice blends. Food Control, 2016, 62: 237-242.

[137]SHEPHARD G S, LEGGOTT N L. Chromatographic determination of the mycotoxin patulin in fruit and fruit juices. Journal of Chromatography A, 2000, 882: 17-22.

[138]KHARANDI N, BABRI M, AZAD J. A novel method for determination of patulin in apple juices by GC-MS. Food Chemistry,2013, 141: 1619-1623.

[139]BELTRÁN E, IBÁÑEZ M, SANCHO J V, HERNÁNDEZ F.Determination of patulin in apple and derived products by UHPLCMS/MS. Study of matrix effects with atmospheric pressure ionisation sources. Food Chemistry, 2014, 142: 400-407.

[140]MOHAMMADIA A, TAVAKOLI R, KAMANKESH M, RASHEDI H, ATTARAN A, DELAVAR M. Enzyme-assisted extraction and ionic liquid-based dispersive liquid-liquid microextraction followed by high-performance liquid chromatography for determination of patulin in apple juice and method optimization using central composite design. Analytica Chimica Acta, 2013, 804: 104-110.

[141]MARSOL-VALL A, BALCELLS M, ERAS J, CANELAGARAYOA R. A rapid gas chromatographic injection-port derivatization method for the tandem mass spectrometric determination of patulin and 5-hydroxymethylfurfural in fruit juices.Journal of Chromatography A, 2016, 1453: 99-104.

[142]WU R-N, DANG Y-L, NIU L, HU H. Application of matrix solid-phase dispersion-HPLC method to determine patulin in apple and apple juice concentrate. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis, 2008, 21: 582-586.

[143]GASPAR E M S M, LUCENA A F F. Improved HPLC methodology for food control-furfurals and patulin as markers of quality. Food Chemistry, 2009, 114: 1576-1582.

[144]MURILLO-ARBIZU M, AMÉZQUETA S, GONÁZLEZ-PEÑAS E,DE CERAIN. Occurrence of patulin and its dietary intake through apple juice consumption by Spanish population. Food Chemistry,2009, 113: 420-423.

[145]MURILLO M, GONÁZLEZ-PEÑAS E, AMÉZQUETA S.Determination of patulin in commercial apple juice by micellar electrokinetic chromatography. Food and Chemical Toxicology, 2008,46: 57-64.

[146]VÍCTOR-ORTEGA M D, LARA F J, GARCÍA-CAMPAÑA A M,DEL OLMO-IRUELA M. Evaluation of dispersive liquid-liquid microextraction for the determination of patulin in apple juices using micellar electrokinetic capillary chromatography. Food Control, 2013,31: 353-358.

[147]BAERT K, DE MEULENAER B, KASASE C, HUYGHEBAERT A,OOGHE W, DEVLIEGHERE F. Free and bound patulin in cloudy apple juice. Food Chemistry, 2007, 100: 1278-1282.

[148]LI J-K, WU R-N, HU Q-H, WANG J-H. Solid-phase extraction and HPLC determination of patulin in apple juice concentrate. Food Control, 2007, 18: 530-534.

[149]FUNES G J, RESNIK S L. Determination of patulin in solid and semisolid apple and pear products marketed in Argentina. Food Control, 2009, 20: 277-280.

[150]MAHAM M, KARAMI-OSBOO R, KIAROSTAMI V, WAQIFHUSAIN S. Novel binary solvents-dispersive liquid-liquid microextraction(BS-DLLME) method for determination of patulin in apple juice using high-performance liquid chromatography. Food Analytical Methods,2013, 6(3): 761-766.

[151]VALLE-ALGARRA F M, MATEO E M, GIMENO-ADELANTADO J V, MATEO-CASTRO R, JIMENEZA M. Optimization of clean-up procedure for patulin determination in apple juice and apple purees by liquid chromatography. Talanta, 2009, 80: 636-642.

[152]CAPRIOTTI A L, CAVALIERE C, GIANSANTI P, GUBBIOTTI R,SAMPERI R, LAGANÀ A. Recent developments in matrix solid-phase dispersion extraction. Journal of Chromatography A, 2010,1217: 2521-2532.

[153]ANENE A, HOSNI K, CHEVALIER Y, KALFAT R, HBAIEB S.Molecularly imprinted polymer for extraction of patulin in apple juice samples. Food Control, 2016, 70: 90-95.

[154]KHORRAMI A R, TAHERKHANI M. Synthesis and evaluation of a molecularly imprinted polymer for pre-concentration of patulin from apple juice. Chromatographia, 2011, 73 (Suppl 1) : S151-S156.

[155]ZHAO D, JIA J, YU X, SUN X. Preparation and characterization of a molecularly imprinted polymer by grafting on silica supports: A selective sorbent for patulin toxin. Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry, 2011, 401: 2259-2273.

[156]ABU-BAKAR N-B, MAKAHLEH A, SAAD B. Vortex-assisted liquid-liquid microextraction coupled with high performance liquid chromatography for the determination of furfurals and patulin in fruit juices. Talanta, 2014, 120: 47-54.

[157]APPELL M, JACKSON M A. Synthesis and evaluation of cyclodextrin-based polymers for patulin extraction from aqueous solutions. Journal of Inclusion Phenomena and Macrocyclic Chemistry, 2010, 68: 117-122.

[158]WU S, DUAN N, ZHANG W, ZHAO S, WANG Z. Screening and development of DNA aptamers as capture probes for colorimetric detection of patulin. Analytical Biochemistry, 2016, 508: 58-64.

[159]MCELROY L J, WEISS C M. The production of polyclonal antibodies against the mycotoxin derivative patulin hemiglutarate.Canadian Journal of Microbiology, 1993, 39: 861-863.

[160]FUNARI R, VENTURA B D, CARRIERI R, MORRA L, LAHOZ E,GESUELE F, ALTUCCI C, VELOTTA R. Detection of parathion and patulin by quartz-crystal microbalance functionalized by the photonics immobilization technique. Biosensors and Bioelectronics, 2015, 67:224-229.

[161]PENNACCHIO A, VARRIALE A, ESPOSITO M G, STAIANO M,D’AURIA S. A near-infrared fluorescence assay method to detect patulin in food. Analytical Biochemistry, 2015, 481: 55-59.

[162]MOK W, LI Y F. Recent progress in nucleic acid aptamer-based biosensors and bioassays. Sensors, 2008, 8: 7050-7084.

[163]TANG L H, LIU Y, ALI M M, KANG D K, ZHAO W A, LI J H.Colorimetric and ultrasensitive bioassay based on a dual-amplification system using aptamer and DNAzyme. Analytical Chemistry, 2012, 84:74711-74717.

[164]FANG G, WANG H, YANG Y, LIU G, WANG S. Development and application of a quartz crystal microbalance sensor based on molecularly imprinted sol-gel polymer for rapid detection of patulin in foods. Sensors and Actuators B, 2016, 237: 239-246.

[165]TANNOUS J, ATOUI A, KHOURY A E, KANTAR S, CHDID N,OSWALD I P, PUEL O, LTEIF R. Development of a real-time PCR assay for Penicillium expansum quantification and patulin estimation in apples. Food Microbiology, 2015, 50: 28-37.

[166]LUQUE M I, RODRÍGUEZ A, ANDRADE M J, GORDILLO R,RODRÍGUEZ M, CÓRDOBA J J. PCR to detect patulin producing moulds validated in foods. Food Control, 2012, 25: 422.

[167]PATERSON R R M. Identification and quantification of mycotoxigenic fungi by PCR. Process Biochemistry, 2006, 41: 1467-1474.

[168]GEISEN R. Molecular detection and monitoring // DIJKSTERHUIS J,SAMSON R A. Food Mycology: A Multifaceted Approach to Fungi and Food. Boca Raton: CRC Press, 2007: 255-278.

[169]NIESSEN L. Current trends in molecular diagnosis of ochratoxin A producing fungi // RAI M. Mycotechnology Present Status and Future Prospects. New Delhi: International Publishing House. 2007: 84-105.

[170]NIESSEN L. PCR based diagnosis and quantification of mycotoxin producing fungi. International Journal of Food Microbiology, 2007,119: 38-46.

[171]LUQUE M I, RODRÍGUEZ A, ANDRADE M J, GORDILLO R,RODRÍGUEZ M, CÓRDOBA J J. Development of a PCR protocol to detect patulin producing moulds in food products. Food Control, 2011,22: 1831-1838.

[172]RODRÍGUEZ A, LUQUE M I, ANDRADE M J, RODRÍGUEZ M,ASENSIO M A, CÓRDOBA J J. Development of real-time PCR methods to quantify patulin-producing molds in food products. Food Microbiology, 2011, 28: 1190-1199.

[173]RODRÍGUEZ A, RODRÍGUEZ M, ANDRADE M J, CÓRDOBA J J.Development of a multiplex real-time PCR to quantify aflatoxin,ochratoxin A and patulin producing molds in foods. International Journal of Food Microbiology, 2012, 155: 10-18.

[174]NOTERMANS S, HUEVELMAN C J, BEUMER R R, MAAS R.Immunological detection of moulds in food: Relation between antigen production and growth. International Journal of Food Microbiology,1986, 3: 253-261.

(责任编辑 赵伶俐)

Occurrence, Control and Determination of Patulin Contamination in Fruits and Fruit Products

NIE JiYun

(Institute of Pomology, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences/Laboratory of Quality & Safety Risk Assessment for Fruit(Xingcheng), Ministry of Agriculture/Quality Inspection and Test Center for Fruit and Nursery Stocks, Ministry of Agriculture(Xingcheng), Xingcheng 125100, Liaoning)

2017-04-26;接受日期:2017-07-24

国家现代农业产业技术体系(CARS-27)、国家农产品质量安全风险评估重大专项(GJFP2017003)、中国农业科学院科技创新工程(CAAS-ASTIP)

联系方式:聂继云,Tel:0429-3598178;E-mail:jiyunnie@163.com