美式英语:为什么单词总缺U?

⊙ By Olivia Goldhill

翻译:Portia

美式英语:为什么单词总缺U?

⊙ By Olivia Goldhill

翻译:Portia

The Case of the Missing “U”s in American English

你学英语也有些年头了,有没有想过为什么英国人用labour而美国人用labor?还有honour与honor、colour与color,等等?过去人们都说这是因为美国人太“懒”,其实是另有原因。一起来探个究竟吧!

When my American editor asked me to research why Brits spell their words with so many extra “u”s, I immediately[马上]knew he had it all wrong. As a British journalist, it’s perfectly obvious to me that we have the correct number of “u”s, and that American spelling has lost its vowels along the way.

“Color,” “honor,” and “favor” all look quite stubby[短而粗的]to me—they’re positively crying out to be adorned[被装饰]with a few extra “u”s.

But it turns out that the “o(u)r” suffix[后缀]has quite a confused history. The Online Etymology[词源]Dictionary reports that -our comes from old French while -or is Latin. English has used both endings for several centuries. Indeed, the first three folios[对开本]of Shakespeare’s plays reportedly used both spellings equally.

But by the late 18th and early 19th centuries, both the US and the UK started to solidify[巩固]their preferences, and did so differently.

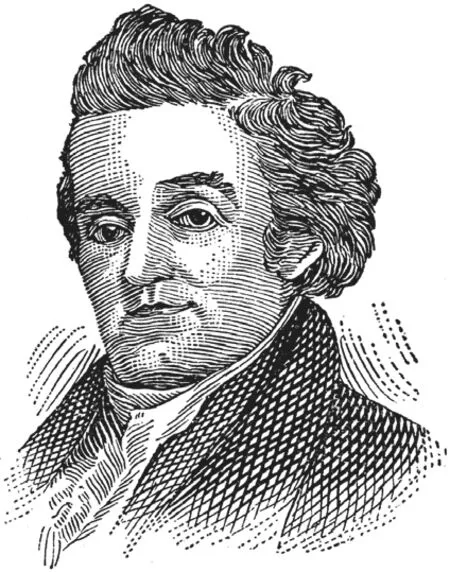

The US took a particularly strong stand[立场]thanks to Noah Webster, American lexicographer[词典编纂者]and co-namesake[同名物]of the Merriam-Webster dictionaries. Webster was a language reformer and the creator of a dictionary in 1806 that attempted to rectify[纠正]some of the inconsistencies[矛盾之处]he observed in English spelling. He preferred to use the –or suffix and also suggested many other successful changes, such as reversing[倒转]“re” to create “theater” and“center,” rather than “theatre” and “centre.”

However, other Webster proposals[建议], such as changing “tongue” to “tung,”“women” to “wimmen,” “island” to “iland,”and “thumb” to “thum” were finally rejected.

Meanwhile in the UK, Samuel Johnson wrote A Dictionary of the English Language in 1755. Johnson was far more of a spelling purist than Webster, and decided that in cases where the origin of the word was unclear, it was more likely to have a French than Latin root. “We have few Latin words, among the terms of domestic[本国的]use, which are not French,” wrote Johnson. And so he preferred –our to –or.

“I have endeavoured[尽力]to proceed[继续]with a scholar’s reverence[敬重]for antiquity[古老的遗物], and a grammarian[文法家]’s regard to the genius[语言特征]of our tongue,”he wrote. As such, he “attempted few alterations[改变].”

So while the UK chose to preserve linguistic[语言学的]roots, the US opted[选择]to modernize spelling. And if you’re wondering which country got it right, the answer is, well, neither. Language is constantly evolving, and the US and UK simply went their different linguistic ways.

参考译文

当美国编辑让我研究一下为什么英国人拼写的单词有那么多额外的“u”时,我立刻意识到,他完全搞错了。身为一名英国记者,我觉得事情再明显不过了,那就是我们对u这个字母的使用恰如其分,而美国人的拼写在演化过程中渐渐把这个元音字母给弄丢了。

在我看来,“color”“honor”和“favor”这些单词的形态都十分短粗,它们迫切需要添几个“u”进行修饰。

但事实上,“o(u)r”这个后缀的发展脉络并不清晰。据“在线词源词典”称,“-our”源自古法语,而“-or”源自拉丁语。英语使用这两个后缀都已有几百年历史。实际上,据说在莎士比亚戏剧集的前三个对开版本中,这两种拼写出现的频率是一样的。

但在18世纪末至19世纪初期间,美国和英国都开始强化其语言偏好,并且努力方向并不相同。

因为美国词典编纂者诺厄・韦伯斯特(《梅里厄姆-韦伯斯特》词典就部分得名于他)的缘故,美国的立场尤其鲜明。韦伯斯特是一位语言改革家,他注意到英语中有拼写不一致的情况,便尝试在其编纂并于1806年出版的一本词典中进行修正。韦伯斯特更喜欢使用“-or”这个后缀,还提出了许多其他被广泛采纳的建议,例如将“re”改为“er”,由此将“theatre”和“centre”分别变为“theater”和“center”等。

但韦伯斯特的另一些建议最终并没有被采纳,例如将“tongue”改为“tung”,将“women”改为“wimmen”,将“island”改为“iland”,以及将“thumb”改为“thum”等。

与此同时,在英国,塞缪尔・约翰逊于1755年编纂了《英语词典》。在追求拼写的纯正性方面,约翰逊的要求远高于韦伯斯特。他认为,一个单词在词源不明的情况下,源于法语比源于拉丁语的可能性更大。约翰逊写道:“就国内使用的词汇来说,源自拉丁语而不是法语的词汇并不多。”所以,他更喜欢使用“-our”这个后缀,而不是“-or”。

他曾写道:“我努力以学者对古文字的敬畏和语法学家对我们语言特征的尊重来进行这项工作。”因此,他“尽量不作改变”。

就这样,英国选择了保留语言的起源,美国则选择了对拼写进行现代化改造。如果你想知道哪个国家做得对,答案是,此事没有对错之分。语言在不断演变,美国和英国只是选择了不同的语言发展道路罢了。

相关链 接

英语our和美语or的常见单词

armo(u)r behavior(u)r cando(u)r colo(u)r favor(u)r harbor(u)r hono(u)r humo(u)r labo(u)r neighbor(u)r rumo(u) splendor(u)r tumo(u)r