黑穗醋栗果实超声波降解多糖的结构及抗糖基化活性

徐雅琴,刘 菲,郭莹莹,陈宏超,王丽波,杨 昱

黑穗醋栗果实超声波降解多糖的结构及抗糖基化活性

徐雅琴,刘 菲,郭莹莹,陈宏超,王丽波,杨 昱※

(东北农业大学理学院,哈尔滨 150030)

为了充分利用黑穗醋栗果实中的多糖资源,该文对水提醇沉,大孔树脂纯化制得黑穗醋栗果实多糖进行超声波降解,并对分离纯化后得到的低分子量多糖的理化性质、结构特征和抗糖基化反应活性进行了研究。利用葡聚糖凝胶Sephadex G-100对降解多糖进行分离纯化,高效液相色谱法测定分子量,气相色谱法测定单糖组成,红外光谱、紫外光谱、刚果红试验和电镜扫描初步表征多糖结构。结果表明:黑穗醋栗果实降解多糖(BCP I)纯度为83.88% ± 0.76%;重均分子量为235 955 Da;BCP I为酸性杂多糖,单糖组成及物质量比为:半乳糖醛酸:鼠李糖:阿拉伯糖:甘露糖:葡萄糖:半乳糖=2.31 : 1.11 : 3.14 : 0.34 : 0.36 : 1.00。BCP I具有多糖的特征吸收峰,不含多酚、蛋白质和核酸;不具有三股螺旋结构,呈现片状不规则的形态。抗糖基化活性测定结果表明BCP I对糖基化反应3个阶段(Amadori产物形成阶段、二羰基化合物形成阶段和糖基化终产物形成阶段)产物的形成均表现出良好的抑制作用,抑制率随浓度与时间的增加而增大。最大抑制率分别为49.55% ± 0.79%,41.82% ± 0.72%和42.01% ± 0.13%,均高于对照氨基胍。研究结果可为后续深入探讨黑穗醋栗果实多糖结构与降血糖活性之间的构效关系提供理论基础。

纯化;超声波;降解;黑穗醋栗果实;多糖;结构;抗糖基化

0 引 言

多糖,又称多聚糖,是自然界含量最丰富的生物聚合物,广泛存在于高等植物、藻类、菌类及动物体内。研究表明多糖具有多种生理活性,如增强免疫调节、抗肿瘤、抗氧化、降血糖、降血脂、抑菌等功效[1-3]。然而大多数天然提取的多糖由于其分子量较大,水溶性差,不利于生物体有效吸收并发挥生物学功能[4]。研究发现通过适当的方法降解多糖,把大分子断裂成在一定分子量范围内的较小片段,可提高其生物活性[5]。目前,有关多糖降解的研究主要集中在酶法降解、化学方法降解和物理方法降解等[6]。酶法降解总体成本较高且专一性酶不易获得[7];化学方法费时、难以控制且对环境不友好[8];物理降解法是一种绿色高效的降解方法,操作简单,可控性好,常用的方法有微波法[9]、辐射法[10]和超声波法[11]。与微波法和辐射法相比,超声波降解在获取所需性质的多糖的同时不会破坏多糖的单元结构[12],从而保证了多糖的生物活性,在食品体系中发挥着重要作用。

黑穗醋栗(Ribes nigrum L.)又称黑加仑,因果实中含有丰富的活性成分[13-14],与蓝莓、树莓和沙棘等一起被称为“第三代”新型水果,受到消费者的广泛关注。近年来,有关黑穗醋栗果实中花色苷、黄酮类、多酚类等活性物质的研究较多[14-15],而对于多糖的研究仅有少量报道。目前,黑穗醋栗果实多糖因其显著的抗氧化、抗肿瘤、降血糖、增强免疫力等多种功效[16-17],正逐渐引起植物学家和医药学家的关注,成为研究热点。课题组前期已从黑穗醋栗果实中提取出具有体外抗氧化活性的天然多糖。但是这些多糖因较大的分子量和较低的溶解度,一定程度上限制了其生物活性的发挥[17-18]。此外,前期研究主要将超声波技术应用于黑穗醋栗多糖的辅助提取,提高多糖提取率[18-19],而有关超声波降解对黑穗醋栗果实多糖结构和活性的影响研究未见报道。因此,本文通过超声波法降解黑穗醋栗果实多糖,初步探讨降解多糖的结构特征和抗糖基化反应活性,为进一步开发利用黑穗醋栗果实多糖资源提供科学依据。

1 材料与方法

1.1 材料与试剂

黑穗醋栗(黑丰)成熟果实,2015年7月采于黑龙江省农科院牡丹江农科所,洗涤后于-20 ℃储藏备用。

大孔吸附树脂D4006,南开大学化工厂;SephadexG-100,瑞典Pharmacia公司进口分装;半乳糖醛酸,上海源叶生物科技有限公司;葡聚糖T-10、T-40、T-70、T-110、T-2000,北京拜尔迪生物公司;D-葡萄糖、D-半乳糖、D-鼠李糖、L-阿拉伯糖、D-甘露糖、D-木糖,美国Sigma公司;其他药品均为分析纯。

1.2 仪器与设备

JY92-2D超声波细胞粉碎机(宁波新芝生物科技股份有限公司);TU-1901双光束紫外可见分光光度计(北京普析通用仪器有限责任公司);FE-20K酸度计(上海精密仪器仪表有限公司);R-205旋转蒸发仪(上海申胜生物技术有限公司);FTS135型傅立叶变换红外光谱仪(美国BID-BAD公司);LC-10AVP高效液相色谱仪(日本岛津公司);GC-2010气相色谱仪(日本岛津公司);S-3400N型显微镜(日本HITACHI公司)。

1.3 方法

1.3.1 黑穗醋栗果实多糖的制备

参考课题组前期研究方法[19],稍加修改。称取一定量黑穗醋栗果实匀浆,按料液比1:20 g/mL加入去离子水,温度80 ℃,电动搅拌,转速200 r/min,提取时间2 h。提取液抽滤、浓缩(50 ℃,真空度< 0.09 MPa),体积分数40%乙醇溶液醇沉,4 ℃冰箱静置过夜,所得沉淀微孔滤膜抽滤(0.45 μm),冻干(-50 ℃,真空度< 15 Pa,干燥24 h),得到粉红色的黑穗醋栗果实粗多糖。

使用D4006型大孔树脂(2.0 cm × 30 cm)对黑穗醋栗果实粗多糖进行纯化,纯化条件:温度25 ℃,上样液质量浓度4.00 mg/mL,洗脱剂为去离子水,洗脱流速1.00 mL/min。将洗脱后的黑穗醋栗果实多糖溶液浓缩(50 ℃,真空度< 0.09 MPa),冻干(-50 ℃,真空度<15 Pa,干燥24 h),命名为BCP,苯酚-硫酸法检测其含量[20]。

1.3.2 黑穗醋栗果实降解多糖的制备

称取2.400 g黑穗醋栗果实多糖(BCP),加入400 mL去离子水使BCP质量浓度为6 mg/mL,充分溶解后,利用超声波细胞粉碎机进行超声降解。超声条件:超声时间30 min,超声温度25 ℃,超声功率600 W。降解后多糖溶液经过透析(3 500 Da,72 h)、浓缩,冻干,得到降解多糖。

将得到的降解多糖配制成15 mg/mL溶液,利用葡聚糖凝胶Sephadex G-100(1.8 cm × 40 cm)分离纯化[21],上样量为1.00 mL,洗脱剂为去离子水,洗脱流速1.0 mL/min,每1.00 mL为一管,收集洗脱液,苯酚-硫酸法跟踪检测至无糖检出。根据洗脱曲线收集多糖组分,浓缩,冻干,得到黑穗醋栗果实降解多糖(BCP I),苯酚-硫酸法测其含量。

1.3.3 黑穗醋栗果实降解多糖理化性质的测定

将BCP I溶解在去离子水、乙醇、乙醚、乙酸乙酯、丙酮、氯仿等溶剂,观察其溶解性。利用酸度计、茚三酮试验、碘-碘化钾试验、斐林试剂反应、三氯化铁反应测定BCP I的化学性质。

1.3.4 黑穗醋栗果实降解多糖分子量和单糖组成测定

分子量测定:液相色谱条件:日本Shimadzu公司高效液相色谱仪;Waters Ultrahydroge 2000色谱柱(7.8 mm × 300 mm);示差折光检测器RID-10A;Shimadzu CLASSVp数据处理工作站;进样量:10 µL;压力:2.3 MPa;洗脱剂:Na2SO4溶液(0.05 mol/L),流速:1.0 mL/min。

将BCP I与标准品(T-10、T-40、T-70、T-110、T-2000)精确配制成2.0 mg/mL溶液,0.45 μm微孔滤膜过滤后进样,测定色谱峰保留时间,GPC分析软件计算得到多糖分子量。

单糖组成的测定:按照聂永心等[22]的方法,将BCP I进行酸水解和衍生化后进样,各单糖标准品也进行衍生化后混合进样,气相色谱仪进行分析检测(肌醇作为内标),计算BCP I的单糖组成。

气相色谱条件:RTX-1701石英毛细管色谱柱(0.25 μm × 30.0 m);氢火焰离子化的检测器(FID);程序升温:180(5 ℃/min)-220 ℃(5 min),220(10 ℃/min)-280 ℃(20 min);汽化和检测器的温度为280 ℃;载气:高纯氮气。

1.3.5 黑穗醋栗果实降解多糖的红外光谱和紫外光谱

采用溴化钾压片法,在4 000~400 cm-1范围内进行红外光谱扫描;采用双光束紫外可见分光光度计在波长190~630 nm范围内进行紫外光谱扫描。

1.3.6 黑穗醋栗果实降解多糖的刚果红试验和扫描电镜测定

参照文献[21]的方法,将BCP I和刚果红试剂配制成不同浓度NaOH溶液,紫外-可见光谱扫描,测量样品溶液的最大吸收波长。将样品BCP I放入离子溅射镀膜仪,样品表面镀一层100 nm左右的金膜,然后利用扫描电镜观察BCP I的形貌特征。

1.3.7 黑穗醋栗果实降解多糖的抗糖基化反应活性测定

[23]的方法,建立牛血清蛋白-葡萄糖糖基化反应体系,以氨基胍作为阳性对照,测定不同质量浓度(0.05、0.20、0.40 mg/mL)BCP I溶液对Amadori产物、二羰基化合物、末期糖基化终产物(advanced glycation end products, AGEs)的抑制作用。

1.4 数据处理

所有试验数据均以3次试验结果的平均数±标准误差(mean ± SD)表示,SPSS软件进行差异显著性分析,以P<0.05作为显著性差异标准。

2 结果与分析

2.1 黑穗醋栗果实降解多糖的制备

BCP经超声波降解,葡聚糖凝胶Sephadex G-100分离纯化后,得到主要组分BCP I,洗脱曲线见图1。如图1所示,洗脱峰为单一吸收峰,峰形对称,且无拖尾现象,说明BCP I为均一组分。苯酚-硫酸法测得多糖回收率为88.04% ± 0.51%,纯度为83.88% ± 0.76%。

图1 BCP I的葡聚糖凝胶SephadexG-100洗脱曲线Fig.1 Elution curve of BCP I by Sephadex G-100

2.2 黑穗醋栗果实降解多糖理化性质

BCP I为白色疏松状(棉花糖状)固体,易溶于水,难溶于乙醇、乙醚、乙酸乙酯等有机溶剂。BCP I水溶液pH值为3.35±0.47,表明它是酸性多糖。BCP I与茚三酮反应呈阴性,表明BCP I中不含有氨基酸、蛋白质;BCP I与三氯化铁反应无颜色变化,表明该多糖不含多酚类物质;与斐林试剂进行反应后,无砖红色沉淀氧化亚铜生成,表明BCP I中不含有游离还原糖。

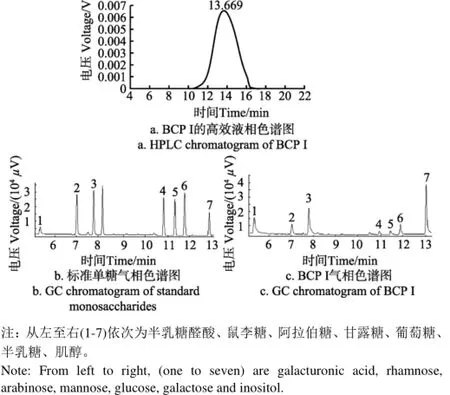

2.3 黑穗醋栗果实降解多糖分子量和单糖组成

BCP I高效液相色谱图见图2a。根据BCP I保留时间(TR=13.669 min),GPC软件计算得到多糖BCP I重均分子量Mw为235 955 Da,数均分子量Mn为34 205 Da,黏均分子量Mz为1 105 803 Da。未降解多糖BCP重均分子量Mw为441 320 Da,数均分子量Mn为58 492 Da,黏均分子量Mz为1 547 684 Da。由此可见,BCP经过超声波处理后,分子量降低,多糖发生降解。

各标准品和BCP I的气相色谱图见图2b,2c。在相同色谱条件下,保留时间可作为定性分析的依据,通过与标准单糖保留时间相比较,可确定多糖样品中的单糖组分。气相色谱分析结果表明,BCP I是由6种单糖组成的酸性杂多糖,单糖组成及物质的量比为:半乳糖醛酸:鼠李糖:阿拉伯糖:甘露糖:葡萄糖:半乳糖=2.31 : 1.11 : 3.14 : 0.34 : 0.36 : 1.00。

图2 BCP I液相色谱和气相色谱图Fig.2 HPLC and GC chromatograms of BCP I

2.4 黑穗醋栗果实降解多糖红外光谱和紫外光谱

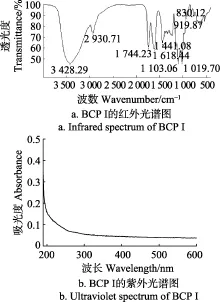

由BCP I红外光谱图(图3a)可知,BCP I在4 000~500 cm-1范围内具有明显的多糖特征吸收峰。3 428.29 cm-1处和2 930.71 cm-1处分别为O-H的伸缩振动峰和C-H伸缩振动峰[24],1 744.23和1 618.44 cm-1处分别为酯化羰基C=O和酯化羧基COO-的伸缩振动峰[25]。此外,吸收峰出现在1 441.08 cm-1处,表明多糖BCP I中含有糖醛酸[26],这与GC测定结果一致。在1 200~1 000 cm-1处存在吸收峰,表明多糖BCP I为吡喃糖[27]。在919.87 cm-1处和830.12 cm-1处分别出现吸收峰,表明多糖存在α-和β-两种糖苷键[28]。

紫外光谱扫描结果如图3b,BCP I在260、280 nm处无吸收,表明降解多糖中不含蛋白质、核酸、花色苷[29]。该测定结果和2.2的结果一致。

图3 BCP I的红外光谱和紫外光谱Fig.3 Infrared and ultraviolet spectra of BCP I

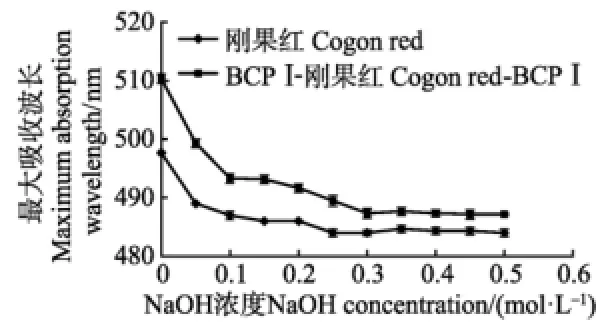

2.5 黑穗醋栗果实降解多糖刚果红试验结果

研究表明,在碱性条件下,与刚果红空白对照相比,具有三股螺旋结构的多糖与刚果红形成的络合物的最大吸收波长(λmax)会发生变化,而如果待测多糖不具有三股螺旋结构,其形成的络合物将会与空白对照溶液λmax变化趋势相近[30]。刚果红、BCP I-刚果红络合物在不同NaOH浓度下最大吸收波长的变化见图4。由图4可以看出,多糖BCP I-刚果红混合溶液与刚果红对照溶液的λmax变化趋势相近,表明BCP I不具有三股螺旋结构。

图4 不同NaOH浓度下刚果红,BCP I-刚果红络合物最大吸收波长(λmax)Fig.4 Maximum absorption wave length (λmax) of Congo red and Congo red-BCP I at various NaOH concentrations

2.6 黑穗醋栗果实降解多糖扫描电镜分析

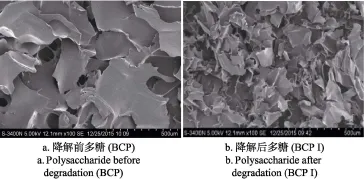

扫描电镜是研究多糖形貌特征的重要方法,超声波降解前后黑穗醋栗多糖的扫描电镜观察结果如图5所示,为多糖在放大100倍时的SEM图像。从图5可以看出,降解前后黑穗醋栗多糖表面均比较光滑,呈片状,形态不规则。然而,与降解前多糖BCP相比(图5a),降解后多糖BCP I片状结构的表面积显著减小(图5b),表明超声波降解黑穗醋栗多糖效果明显。Yan等采用超声波法降解桑黄菌丝多糖时得到同样的结论[5]。

图5 超声波降解前后多糖的扫描电镜图像(放大100倍)Fig.5 SEM images of ultrasonic polysaccharides before and after degradation(× 100 times)

2.7 黑穗醋栗果实降解多糖抗糖基化活性

在非酶促条件下,蛋白质游离氨基与还原糖的羰基经过一系列反应可以产生稳定的末期糖基化终产物(AGEs),该反应叫做非酶糖基化反应[31]。糖基化反应主要3个阶段:初期Amadori产物形成阶段、中期二羰基化合物形成阶段和反应末期终产物AGEs形成阶段。AGEs能够导致许多慢性疾病,如糖尿病肾脏合并症、动脉粥样硬化、老年性痴呆症,严重威胁人类健康[32]。研究表明,抑制剂若能够抑制上述3个阶段中的任一产物的生成,都可以减少AGEs的形成,有利于治疗慢性疾病[33]。

BCP I抗糖基化活性结果如图6所示,不同浓度(0.05,0.20,0.40 mg/mL)BCP I对糖基化反应的3个阶段的产物均有一定的抑制作用;且随着时间和浓度的增加,多糖的抑制率显著增加(P<0.05)。

图6 BCP I和氨基胍抗糖基化作用Fig.6 Antiglycation effects of BCP I and aminoguanidine

如图6a、6b所示,相同浓度下,BCP I的抑制率高于对照氨基胍。第13天时,当BCP I质量浓度为0.40 mg/mL,BCP I对Amadori产物和二羰基化合物的抑制作用均达到最大,抑制率分别为49.55%±0.79%,41.82%± 0.72%,高于对照氨基胍44.58%±1.02%,33.01%±0.28%。此外,由图6c可以看出,第13 天时,不同质量浓度(0.40、0.20、0.05 mg/mL)BCP I对AGEs的最大抑制率分别为42.01%±0.13%,36.86%±0.12%,33.05%±0.09%,均显著高于相应浓度下氨基胍的抑制率(30.45%±0.13%,26.59%±0.20%和23.80%±0.49%)。由此可见,在试验浓度范围内,BCP I对AGEs的抑制作用均高于对照氨基胍。

3 讨 论

研究结果表明超声波降解对黑穗醋栗果实多糖分子量和空间结构产生一定影响。多糖分子量从441 320 Da(BCP)降低至235 955 Da(BCP I),减少了46.53%,同时降解多糖BCP I片状结构的表面积相对于原多糖BCP明显减小。Wang等[34]研究发现,低功率超声条件下,真菌多糖Cs-HKl在3 400和1 064 cm-1处吸收峰减弱,说明超声波导致维持多糖二级结构的氢键发生断裂,而在高功率条件下则裂解为大小不同的多糖碎片。Zhu等[12]对冬虫夏草菌丝多糖进行超声波降解,发现超声波处理不改变多糖的特征属性,单糖残基的组成和糖苷键的类别没有改变,但是分子量和特性黏度降低,并且超声处理后的α-螺旋性增强,降解多糖的抗肿瘤活性显著增加。Yu等[35]对紫菜多糖进行超声波降解,得到低分子量、低黏度,高抑制癌细胞增值活性的降解多糖。Sun等[36]通过超声波降解,得到系列低分子量海洋石斛降解多糖,降解多糖在清除自由基、抑制脂质过氧化以及红细胞溶血试验中均比未降解多糖表现出更优良的性能。由此可见,超声波主要导致多糖分子量、单糖组成、分支度以及空间结构发生变化,进而对多糖的溶解度、黏度、结晶度以及生物活性产生一定的影响。目前,有关超声波降解的确切机制还不明确。有研究者认为[5,35],与化学或热分解不同,超声波降解是非随机过程,链断裂主要在分子的中心位置发生。本试验首次对超声波降解后黑穗醋栗多糖的结构特征与抗糖基化活性进行了初步研究,但是有关超声波降解黑穗醋栗果实多糖的作用机制还有待进一步深入探讨。

4 结 论

1)黑穗醋栗果实多糖经过超声波降解,葡聚糖凝胶Sephadex G-100分离纯化后,得到均一降解多糖,纯度达到83.88%±0.76%,重均分子量为235 955 Da。降解多糖为酸性杂多糖,单糖组成的物质量比为:半乳糖醛酸:鼠李糖:阿拉伯糖:甘露糖:葡萄糖:半乳糖=2.31 : 1.11 : 3.14 : 0.34 : 0.36 : 1.00。

2)黑穗醋栗果实降解多糖具有多糖的特征结构,不含蛋白、核酸和多酚类物质。此外,降解多糖不具有三股螺旋结构,表面呈片状,形态不规则。

3)黑穗醋栗果实降解多糖对糖基化反应3个阶段产物的形成均表现出良好的抑制作用,同一浓度下,抑制率均高于对照氨基胍。因此,黑穗醋栗果实降解多糖可作为较好的糖基化反应抑制剂。

[参 考 文 献]

[1] 景永帅,张丹参,吴兰芳,等. 荔枝低分子量多糖的分离纯化及抗氧化吸湿保湿性能分析[J]. 农业工程学报,2016,32(9):277-283.

Jing Yongshuai, Zhang Danshen, Wu Lanfang, et al. Purification, antioxidant, hygroscopicity and moisture retention activity of low molecular weight polysaccharide from Litchi chinensis[J]. Transactions of the Chinese Society of Agricultural Engineering (Transactions of the CSAE), 2016, 32(9): 277-283. (in Chinese with English abstract)

[2] Chen R Z, Meng F L, Liu Z Q, et al. Antitumor activities of different fractions of polysaccharide purified from Ornithogalum caudatum Ait[J]. Carbohydrate Polymers, 2010, 80(3): 845-851.

[3] Zhao R, Jin R, Chen Y, et al. Hypoglycemic and hypolipidemic effects of Lycium barbarum polysaccharide in diabetic rats[J]. Chinese Herbal Medicines, 2015, 7(4): 310-315.

[4] Zhou C S, Yu X J, Zhang Y Z, et al. Ultrasonic degradation, purification and analysis of structure and antioxidant activity of polysaccharide from Porphyra yezoensis Udea[J]. Carbohydrate Polymers, 2012, 87(3): 2046-2051.

[5] Yan J K, Wang Y Y, Ma H L, et al. Ultrasonic effects on the degradation kinetics, preliminary characterization and antioxidant activities of polysaccharides from Phellinus linteus mycelia[J]. Ultrasonics Sonochemistry, 2016, 29: 251-257.

[6] Li S J, Xiong Q P, Lai X P, et al. Molecular modification of polysaccharides and resulting bioactivities[J]. Comprehensive Review in Food Science and Food Safety, 2016, 15(2): 237-250.

[7] Ren M, Yan W, Yao W, et al. Enzymatic degradation products from a marine polysaccharide YCP with different immunological activity and binding affinity to macrophages, hydrolyzed by alpha-amylases from different origins[J]. Biochimie, 2010, 92(4): 411-417.

[8] Anastyuk S D, Imbs T I, Shevchenko N M, et al. ESIMS analysis of fucoidan preparations from Costaria costata, extracted from alga at different life-stages[J]. Carbohydrate Polymers, 2012, 90(2): 993-1002.

[9] Li B, Liu S, Xing R E, et al. Degradation of sulfated polysaccharides from Enteromorpha prolifera and their antioxidant activities[J]. Carbohydrate Polymers, 2013, 92(2): 1991-1996.

[10] Duy N N, Phu D V, Anh N T, et al. Synergistic degradation to prepare oligochitosan by gamma-irradiation of chitosan solution in the presence of hydrogen peroxide[J]. Radiation Physics and Chemistry, 2011, 80(7): 848-853.

[11] 王丽波,徐雅琴,于泽源,等. 南瓜籽多糖乙醇分级沉淀与超声波改性研究[J]. 农业工程学报,2015,46(8):206-210.

Wang Libo, Xu Yaqin, Yu Zeyuan, et al. Ethanol fractional precipitation and ultrasonic modification of pumpkin polysaccharides[J]. Transactions of the Chinese Society of Agricultural Engineering (Transactions of the CSAE), 2015, 46(8): 206-210. (in Chinese with English abstract)

[12] Zhu Z Y, Wei P, Li Y Y, et al. Effect of ultrasonic treatment on structure and antitumor activity of mycelial polysaccharides from Cordyceps gunnii[J]. Carbohydrate Polymers, 2014, 114: 12-20.

[13] Gopalan A, Reuben S C, Ahmed S, et al. The health benefits of blackcurrants[J]. Food & Function, 2012, 3(8): 795-809.

[14] Tabart J, Kevers C, Evers, D, et al. Ascorbic acid, phenolic acid, flavonoid, and carotenoid profiles of selected extracts from Ribes nigrum[J]. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 2011, 59(9): 4763-4770.

[15] Feng C Y, Su S, Wang L J, et al. Antioxidant capacities and anthocyanin characteristics of the black–red wild berries obtained in Northeast China[J]. Food Chemistry, 2016, 204: 150-158.

[16] Messing J, Niehues M, Shevtsova A, et al. Antiadhesive properties of arabinogalactan protein from Ribes nigrumseeds against bacterial adhesion of Helicobacter pylori[J]. Molecules, 2014, 19(3): 3696-3717.

[17] Xu Y Q, Cai F, Yu Z Y, et al. Optimisation of pressurised water extraction of polysaccharides from blackcurrant and its antioxidant activity[J]. Food Chemistry, 2016, 194: 650-658.

[18] Xu Y Q, Zhang L, Yang Y, et al. Optimization of ultrasound–assisted compound enzymatic extraction and characterization of polysaccharides from blackcurrant[J]. Carbohydrate Polymers, 2015, 117: 895-902.

[19] 徐雅琴,宋秀梅,任中杰. 黑穗醋栗果实多糖清除自由基活性及结构初步研究[J]. 现代食品科技,2013,29(12):2821-2825.

Xu Yaqin, Song Xiumei, Ren Zhongjie. Analysis of structure and free radical scavenging activities of Ribes nigrumpolysaccharides[J]. Modern Food Science and Technology, 2013, 29(12): 2821-2825. (in Chinese with English abstract)

[20] Dubois M, Gilles K A, Hamilton J K, et al. Colorimetric method for determination of sugars and related substances[J]. Analytical Chemistry, 1956, 28(3): 350-356.

[21] Xu Y Q, Liu G J, Yu Z Y, et al. Purification, characterization and antiglycation activity of a novel polysaccharide from black currant[J]. Food Chemistry, 2016, 199: 694-701.

[22] 聂永心,姜红霞,苏延友,等. 黄伞子实体多糖的提取纯化及单糖组成分析[J]. 食品与发酵工业,2010,36(4):198-200.

Nie Yongxin, Jiang Hongxia, Su Yanyou, et al. Purification and monosaccharide composition analysis of polysaccharide from fruit bodies of pholiota adiposa[J]. Food and Fermentation Industries, 2010, 36(4): 198-200. (in Chinese with English abstract)

[23] Xiang J, Fei K, Kong F, et al. Prediction of the antiglycation activity of polysaccharides from Benincasa hispida, using a response surface methodology[J]. Carbohydrate Polymers, 2016, 151: 358-363.

[24] Jin T, Jing N, Li D, et al. Characterization and antioxidant activities of degraded polysaccharides from Poria cocos sclerotium[J]. Carbohydrate Polymers, 2014, 105: 121-126.

[25] Chen X M, Jin J, Tang J, et al. Extraction, purification, characterization and hypoglycemic activity of a polysaccharide isolated from the root of Ophiopogon japonicus[J]. Carbohydrate Polymers, 2011, 83(2), 749-754.

[26] Yang X L, Wang R F, Zhang S P, et al. Polysaccharides from Panax japonicus C.A. Meyer and their antioxidant activities[J]. Carbohydrate Polymers, 2014, 101: 386-391.

[27] Wang Z B, Pei J J, Ma H L, et al. Effect of extraction media on preliminary characterizations and antioxidant activities of Phellinus linteus polysaccharides[J]. Carbohydrate Polymers,2014, 109: 49-55.

[28] Li X L, Xiao J J, Zha X Q, et al. Structural identification and sulfated modification of an antiglycation Dendrobium huoshanense polysaccharide[J]. Carbohydrate Polymers, 2014, 106: 247-254.

[29] 黎英,陈雪梅,严月萍,等. 超声波辅助酶法提取红腰豆多糖工艺优化[J]. 农业工程学报,2015,31(15):293-301.

Li Ying, Chen Xuemei, Yan Yueping, et al. Optimal extraction technology of polysaccharides from red kindey beanusing ultrasonic assistant with enzyme[J]. Transactions of the Chinese Society of Agricultural Engineering (Transactions of the CSAE), 2015, 31(15): 293-301. (in Chinese with English abstract)

[30] He P, Zhang A, Zhang F, et al. Structure and bioactivity of a polysaccharide containing uronic acid from Polyporus umbellatus, sclerotia[J]. Carbohydrate Polymers, 2016, 152: 222-230.

[31] Raghu G, Jakhotia S, Yadagiri Reddy P, et al. Ellagic acid inhibits non-enzymatic glycation and prevents proteinuria in diabetic rats[J]. Food & Function, 2016, 7(3): 1574-1583.

[32] Wang X, Zhang L S, Dong L L. Inhibitory effect of polysaccharides from pumpkin on advanced glycation end-products formation and aldose reductase activity[J]. Food Chemistry, 2012, 130(4): 821-825.

[33] Sompong W, Adisakwattana S. Inhibitory effect of herbal medicines and their trapping abilities against methylglyoxalderived advanced glycation end-products[J]. BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 2015, 15(1): 1-8.

[34] Wang Z M, Cheung Y C, Leung P H, et al. Ultrasonic treatment for improved solution properties of a highmolecular weight exopolysaccharide produced by a medicinal fungus[J]. Bioresource Technology, 2010, 101(14): 5517-5522.

[35] Yu X J, Zhou C S, Yang H, et al. Effect of ultrasonic treatment on the degradation and inhibition cancer cell lines of polysaccharides from Porphyra yezoensisd[J]. Carbohydrate Polymers, 2015, 117: 650-656.

[36] Sun L Q, Wang L, Li J, et al. Characterization and antioxidant activities of degraded polysaccharides from two marine Chrysophyta[J]. Food Chemistry, 2014, 160: 1-7.

Structure and antiglycation activity of polysaccharides after ultrasonic degradation from blackcurrant fruit

Xu Yaqin, Liu Fei, Guo Yingying, Chen Hongchao, Wang Libo, Yang Yu※

(College of Science, Northeast Agricultural University, Harbin 150030, China)

Blackcurrant (Ribes nigrum L.) is a kind of small berry with many health-beneficial substances, such as organic acids, unsaturated fatty acids, vitamins, polysaccharides, flavonoids, and anthocyanins. Recently, polysaccharide from blackcurrant (BCP) has received considerable attention for their prominent benefits to human health, including immunostimulation, antitumor, antimicrobial, antioxidant, and anti-inflammatory activities. Previous work from our laboratory had isolated BCP which showed apparent antioxidant activities in vitro. However, the polysaccharides’ high molecular weight and low solubility in water limit their absorption and utilization in the body. Thus, the degradation of polysaccharides should be carried out to improve the specific and unique properties. Notably, ultrasonic irradiation has been recently viewed as a new technique for the degradation of polysaccharides, mainly due to the fact that the reduction in the molecular weight is simply splitting the most susceptible chemical bonds without causing any major changes in the chemical nature of polysaccharides. At present, there are no reports on preparing degraded BCP with the method of ultrasonic degradation. In this study, the BCP was obtained through water extraction, 40% alcohol precipitation, and purification with D4006 macroporous resin. The BCP was dissolved in water (6 mg/mL) and then was degraded by ultrasonication at 600 W, 25 °C for 30 min. The degraded polysaccharide (BCP I) was obtained through the subsequent separation with Sephadex G-100. Physical and chemical properties, structural characterization and antiglycation activity of BCP I were preliminarily studied. The molecular weight was determined by high performance liquid chromatography, and the monosaccharide composition was determined by gas chromatography. Infrared spectrum, Congo red and electron microscopy were used to characterize the structure of the polysaccharides. The results showed that the purity of BCP I was 83.88%±0.76%, and the weight average molecular weight was 235 955 Da. BCP I was acidic polysaccharide, and consisted of galacturonic acid, rhamnose, arabinose, mannose, dextrose and galactose in a ratio of 2.31 : 1.11 : 3.14 : 0.34 : 0.36 : 1.00. Fourier transform infrared spectrum showed that BCP I had obvious characteristic peaks of polysaccharides, and BCP I was a pyranose form of sugar containing both α-type and β-type glycosidic linkage. Ultraviolet spectrum showed that BCP I did not contain anthocyanins, proteins and nucleic acids. Scanning electron microscope and Congo red test showed that BCP I exhibited sheet structure and had no triple helix structure, and the surface area of BCP I was reduced compared with BCP. The results of antiglycation assay showed that BCP I exhibited significant inhibitory effects on the product formation of 3 stages of glycation reaction, and the inhibitory rate increased with the increase of concentration and time. The maximum inhibitory rates were 49.55%±0.79%, 41.82%±0.72% and 42.01%±0.13%, respectively, which were higher than those of the control aminoguanidine (30.45%±0.13%,26.59%±0.20% and 23.80%±0.49%). Thus, BCP I can be considered as a kind of potential inhibitor of protein glycation. The results can provide a theoretical basis for further study on the structure-activity relationship between structure and hypoglycemic activity of the polysaccharides from blackcurrant.

purification; ultrasound wave; degradation; blackcurrant fruits; polysaccharides; structure; antiglycation activity

10.11975/j.issn.1002-6819.2017.05.042

TS218

A

1002-6819(2017)-05-0295-06

徐雅琴,刘 菲,郭莹莹,陈宏超,王丽波,杨 昱. 黑穗醋栗果实超声波降解多糖的结构及抗糖基化活性[J]. 农业工程学报,2017,33(5):295-300.

10.11975/j.issn.1002-6819.2017.05.042 http://www.tcsae.org

Xu Yaqin, Liu Fei, Guo Yingying, Chen Hongchao, Wang Libo, Yang Yu. Structure and antiglycation activity of polysaccharides after ultrasonic degradation from blackcurrant fruit[J]. Transactions of the Chinese Society of Agricultural Engineering (Transactions of the CSAE), 2017, 33(5): 295-300. (in Chinese with English abstract)

doi:10.11975/j.issn.1002-6819.2017.05.042 http://www.tcsae.org

2016-10-21

2017-02-03

国家自然科学青年基金资助项目(NO. 31600276);黑龙江省自然科学基金资助项目(NO. C2015004);东北农业大学SITP计划项目(201710224147)

徐雅琴,女,教授。研究方向:天然产物提取及活性研究。哈尔滨 东北农业大学理学院,150030。Email:xuyaqin@neau.edu.cn

※通信作者:杨 昱,女,博士,副教授。研究方向:天然产物提取及活性研究。哈尔滨 东北农业大学理学院,150030。Email:yangyu_002@163.com