The Effect of Home-Based Cardiac Rehabilitation on Functional Capacity,Behavior, and Risk Factors in Patients with Acute Coronary Syndrome in China

Rongjing Ding, Jianchao Li, Limin Gao, Liang Zhu, Wenli Xie, Xiaorong Wang,Qin Tang, Huili Wang, and Dayi Hu

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) has been the leading cause of death in China, responsible for almost a quarter of the disease burden, resulting in substantial direct cost in terms of health care, as well as indirect costs on account of productivity losses [1]. It is estimated that China will lose $18 billion in national income from premature deaths due to heart disease,stroke, and diabetes, and will stand to lose $558 billion in the next 10 years [2]. Although patients with CVD receive optimal secondary prevention medication and high-technology therapeutic procedures,studies show that they still experience repeated ischemia, myocardial infarction, rehospitalization,and revascularization [3–5]. Another challenge for patients with CVD is to optimize the disability-free survival, including active participation in social and economic life for patients after cardiovascular events or intervention [6]. Previous studies showed that the quality life of patients with CVD reduced dramatically: 30% of patients limited their activity[7], 30.9% of patients had depression or anxiety that led to poor quality of life [8], and 25% of patients stopped engaging in sexual activities [9]. Cardiac rehabilitation, defined as coordinated, multifaceted intervention designed to optimize a cardiac patient’s physical, psychological, and social functioning, in addition to stabilizing, slowing, or even reversing the progression of the underlying atherosclerotic processes, thereby reducing morbidity and mortality, is the best way to improve CVD patients’outcome [10].

There is a great need for cardiac prevention and rehabilitation in China. The first national survey on the availability of cardiac rehabilitation was performed in 2012, and the results showed that the availability of cardiac rehabilitation services in Chinese tertiary hospitals was only 24% [11], which was the lowest compared with the United States,Europe, Canada, Australia, and Latin America[12–17]. This demonstrated the low capacity of the Chinese health system to control and manage CVD.

Although cardiac rehabilitation is supported by governments and covered by insurance, participation rates in the United States and Europe are still low, estimated at 10–30% [18]. The barriers to accessing traditional cardiac rehabilitation in the United States and Europe include transport diffi -culties, work schedules, social commitments, lack of perceived need, and functional impairment [19].Traditional cardiac rehabilitation faces substantial challenges in terms of cost and access, and does not meet the needs of most groups most in need of risk factor reduction, such as older adults, women, lowincome populations, and employees. The homebased cardiac rehabilitation model has been shown to be a feasible alternative to avoid various barriers related to care center–based programs in the United States and Europe [20].

Home-based cardiac rehabilitation may be the best way to overcome barriers in China. Up to now,no home-based cardiac rehabilitation has existed in China. The main barrier in China for cardiac rehabilitation development includes lack of cardiac rehabilitation staff, financial limitations, space limitations, and lack of patients’ perceived need [11].We set up a standardized home-based cardiac rehabilitation program with a heart manual and home exercise video in China and tested its effect on exercise capacity, health behavior, and risk factors.

Methods/Design

Study Design and Randomization

This study is a randomized controlled trial with a 3-month prospective follow-up evaluating the effect of a home-based cardiac rehabilitation program versus usual care on exercise capacity, risk factors, and health behavior in a population with acute coronary syndrome (ACS). The Ethics Committee of Peking University People’s Hospital approved the study design and protocol. Informed consent was obtained from patients at the time of the enrollment.

Eighty patients in whom ACS had been diagnosed within the previous 6 months were recruited into the study from three communities affiliated with Peking University People’s Hospital, Beijing Electrical Power Hospital, and Beijing Jingmei Group General Hospital respectively. The diagnosis of ACS was based on the presence of chest pain plus verification by diagnostic electrocardiogram changes, troponin I level, or troponin I level equivalent to or greater than the 99th percentile of the upper reference limit. After informed consent had been provided, with use of a computer-generated random allocation sequence (1:2 allocation ratio)(http://www.randomization.com), 28 patients were allocated to the control group to receive usual care,while 52 people were allocated to the intervention group to participate to the 3-month cardiac rehabilitation intervention program.

The inclusion criteria were as follows: patients were required to be 18–75 years of age and to have received a diagnosis of ACS within the previous 6 months with a low–medium risk profile, of either sex, and able to give informed consent. The exclusion criteria were as follows: inability to sign the informed consent form, patients with a high-risk profile of ACS, presence of cognitive impairment(Mini-Mental State Examination score less than 18), permanently bedridden or fully dependent on a wheelchair, and patients with unstable angina,uncontrolled arrhythmia, hyperpyrexia, dehydration, severe heart failure, severe cancer, or neurological impairment.

For the home-based group, the rehabilitation program structure included all core components of a comprehensive cardiac rehabilitation program as developed by the American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation [10].The patients were enrolled through an initial assessment and then assessed at certain intervals (once every month until 3 months) at a community hospital. The assessment included baseline assessment of cardiovascular risk factors (direct measurement of anthropometric data, laboratory measurement of blood lipids and glucose, blood pressure measurement, and self-reported smoking, exercise, and nutrition habits, psychological status evaluation,quality of life) and counseling to achieve optimal lifestyle-related health behaviors. Each participant was provided with five cardiac rehabilitation prescriptions as follows: exercise prescription, medication prescription, psychological prescription, diet prescription, and a smoking cessation prescription.Each participant met the cardiac rehabilitation physician at the initial assessment, and together they set goals for cardiovascular risk reduction and the participant received at least a 30-min cardiac rehabilitation prescription to make sure the patient fully understood how to the perform cardiac rehabilitation prescription at home.

The 3-month program consisted of a self-help heart manual for healthy diet, regular exercise,smoking cessation, stress management, and risk factor management, and a home exercise video.The patients were asked to read the manual and watch the video during the first week after initiation of the home-based cardiac rehabilitation program.The daily exercise program at home consisted of moderate levels of walking as the main mode of physical activity based on the physicians’ exercise prescription, and the heart rate and blood pressure were recoded every day before and after exercise.Information about how to contact the rehabilitation nurse was provided. Follow-up arrangements were as follows: telephone contact each week during the first month, every 2 weeks for the second month,and once for the third month by cardiac rehabilitation nurse, including discussion of the contents of the manual with the patient and partner and setting of individual objectives with the patient with respect to risk factors, smoking cessation, diet, and exercise. Patients were asked to see the cardiac rehabilitation physician in the community clinic for updated cardiac rehabilitation assessment and undated cardiac rehabilitation prescription and received face-to face education three times in in the community hospital, including education on how to identify angina, coronary heart disease medication, how to do exercise, and how to maintain a healthy lifestyle.

For the usual care group, patients received paper education material for a healthy lifestyle, healthy behaviors, and risk factor management, received standard CVD secondary medication, and regular follow-up with the cardiologist. There was no comprehensive evaluation, no exercise prescription,no counseling to achieve optimal lifestyle-related health behaviors and meet cardiac rehabilitation physician, and no joint setting of goals for cardiovascular risk reduction.

Outcome Measures

The primary outcome measures included exercise capacity as evaluated with the 6-min walk distance (6MWD), self-reported exercise, and nutrition habits. Secondary outcome measures included cardiac risk factor reduction achievement rate for blood lipid levels, glucose levels, and blood pressure, quality of life evaluated with the 12-item Short Form Health Survey (SF-12), depression and anxiety evaluation with the 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) and the 7-item General Anxiety Disorder Questionnaire (GAD-7), and exercise adherence.

Statistical Analysis

All data were analyzed with JMP, version 9 (SAS Institute, Minneapolis, Minnesota, United States),and a two-tailedPvalue of 0.05 or less was considered statistically significant.

We analyzed the distribution of baseline data and calculated means (and standard deviations) or medians (and ranges) for continuous variables and numbers (and percentages) for categorical data.Differences between baseline characteristics and 3-month follow-up data between the control group and the intervention group or between the cardiac rehabilitation group before invention and after invention were tested by an independentttest or a pairedttest for continuous variables and the chisquare test for all dichotomous variables. Fisher exact probabilities were calculated when they were expected.

Results

Baseline Data

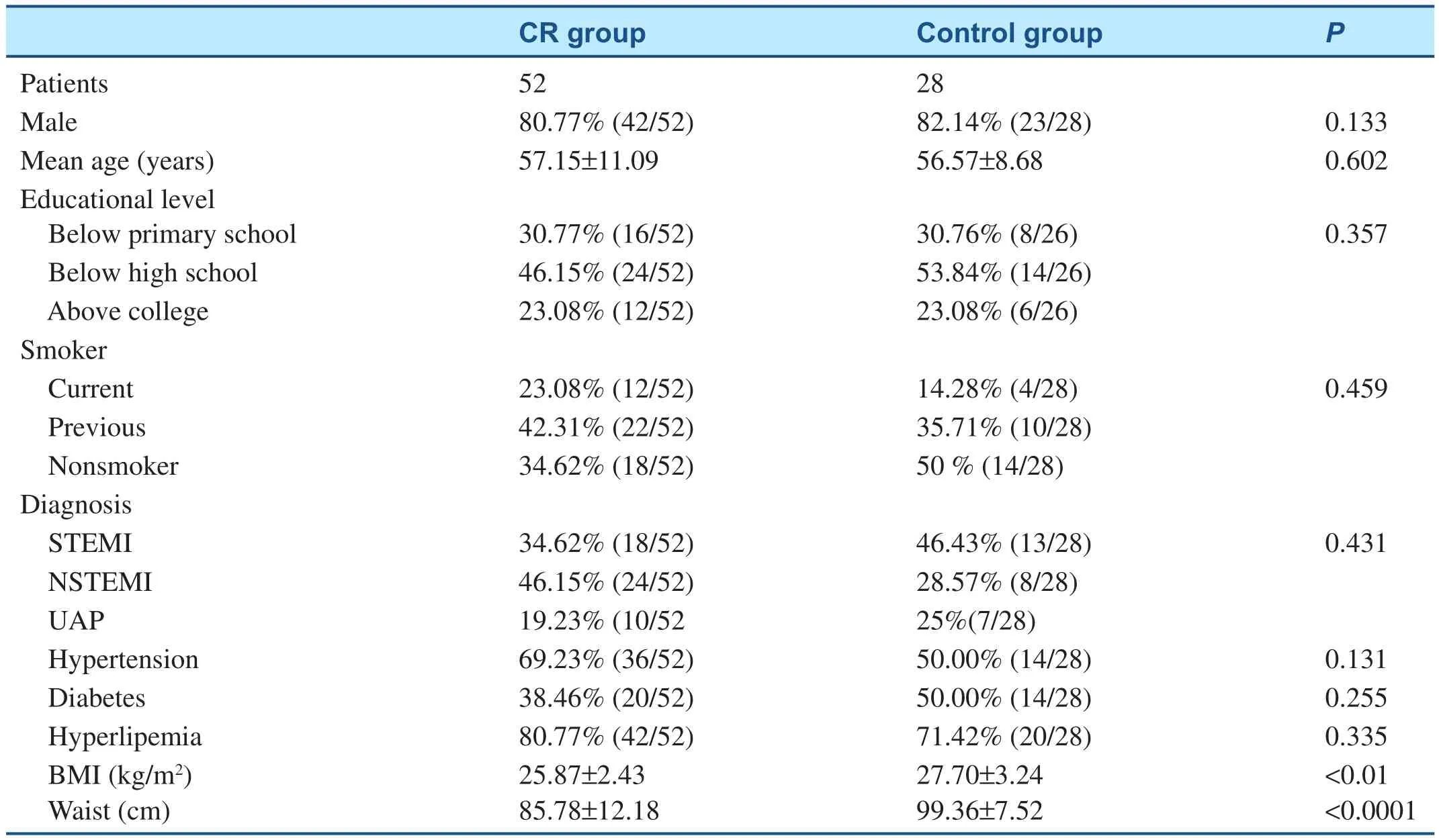

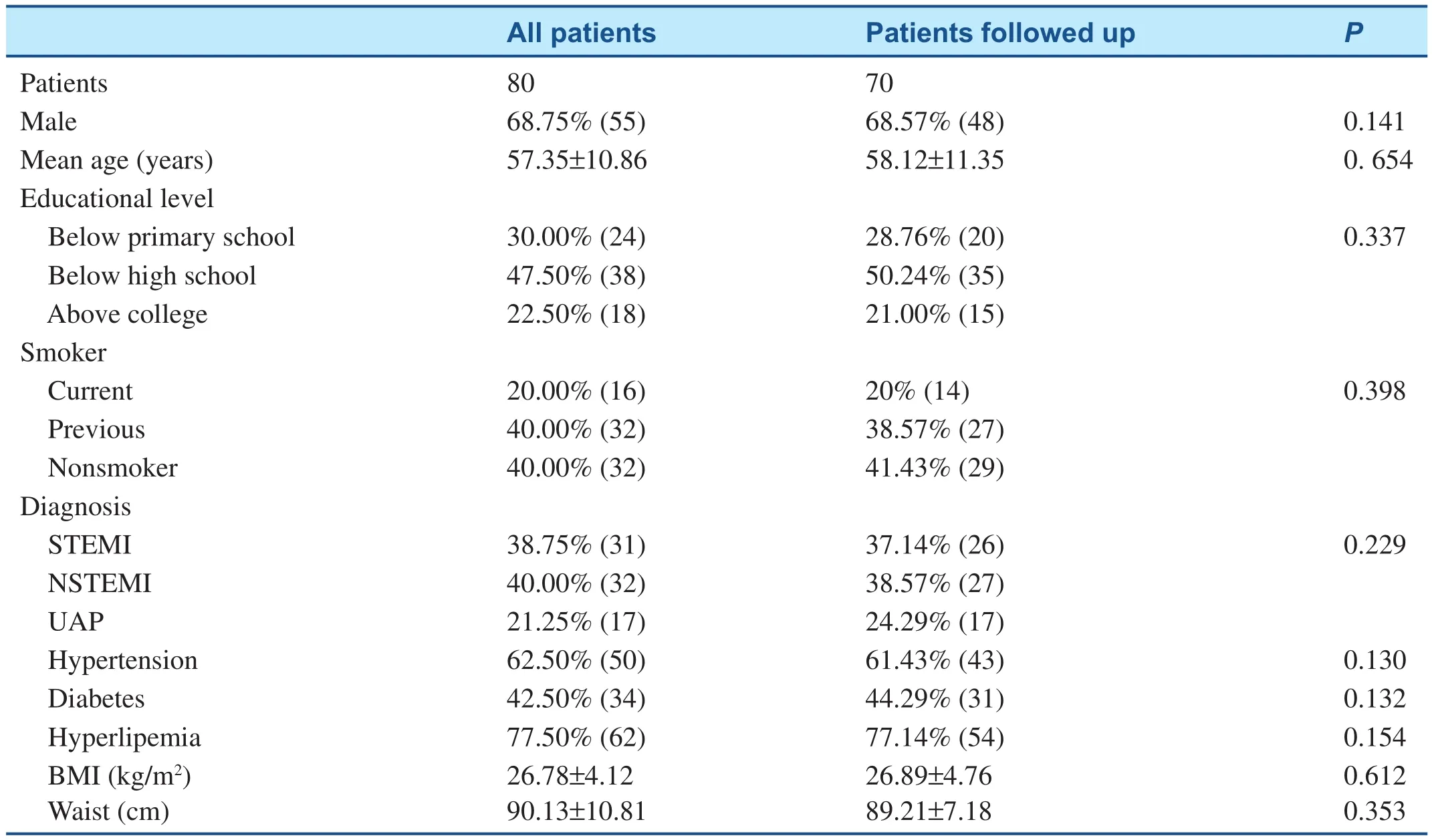

This study enrolled a total of 80 patients with ACS,of whom 52 patients were allocated to the cardiac rehabilitation group and 28 patients were allocated to the control group. There were no significant differences in age, sex, education level, etiological diagnosis, and complications between the two groups (see Table 1). Seventy patients (87.5%) completed follow-up, four patients were lost to followup in the cardiac rehabilitation group (follow-up rate of 92.3%), and six patients were lost to followup in the control group (follow-up rate of 78.6%).One of the reasons for loss of patients to followup was their refusal to be evaluated by the 6MWD and questionnaires, another reason was a move to another city. There were no differences regarding characteristics between all patients and the patients being followed up (Table 2). Social functioning assessment demonstrated that only eight patients(12.5%) resumed normal work, while four patients(6.25%) changed to a lighter workload, eight patients (12.50%) retired ahead of schedule, eight patients (12.50%) were on long term sick leave, and 36 patients (56.25%) retired on schedule. Twenty patients (31.25%) did not resume normal work after diagnosis of ACS. Apart from those who retired on schedule, 78.13%(50/64) of current employees did not resume normal work after diagnosis of ACS.

Comparison of 6MWD, Mental Status,and Quality of Life Before and After Intervention

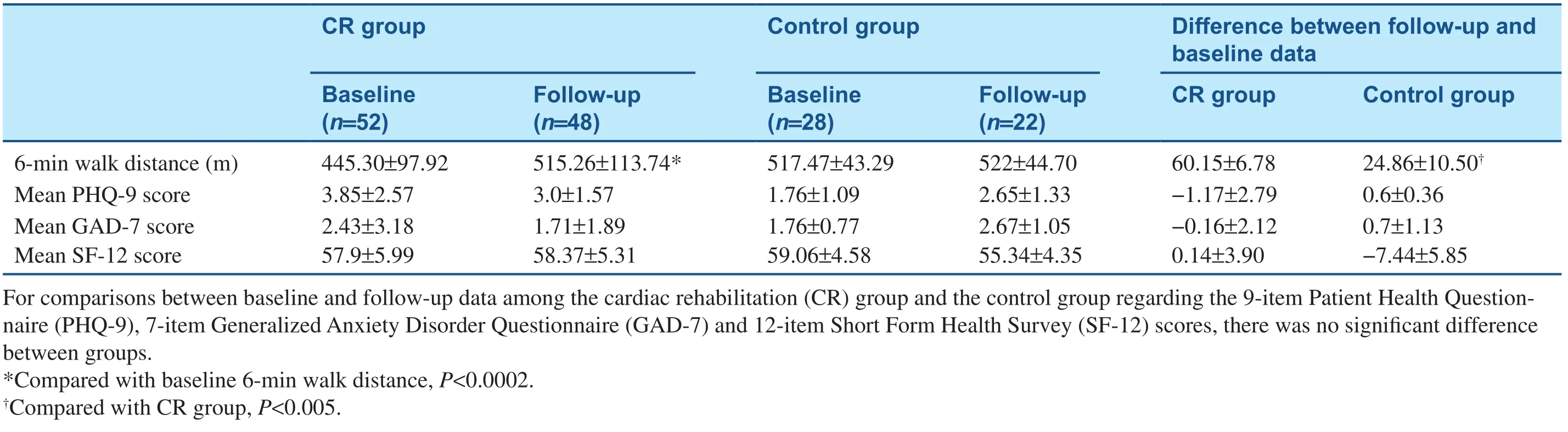

The baseline 6MWD in the cardiac rehabilitation group was lower than that in the control group.After 3 months of home-based cardiac rehabilitation intervention, the 6MWD in the cardiac rehabilitation group increased significantly. The difference in the 6MWD at the baseline and at the 3-month follow-up in the cardiac rehabilitation group was significantly higher than that in the control group(P<0.005) (see Table 3).

There was no significant difference in baseline PHQ-9, GAD-7, and SF-12 scores between the cardiac rehabilitation group and the control group, but after 3 months of treatment, the PHQ-9 and GAD-7 scores showed a decreasing trend in the cardiac rehabilitation group and an increasing trend in the control group, and the SF-12 score had the opposite change (see Table 3). The reason for no signifi-cant difference regarding the PHQ-9, GAD-7, and SF-12 baseline scores may be associated with the relatively small number of patients and lower statistical power.

Comparison of Blood Glucose Levels,Blood Lipid Levels, and Blood Pressure Control Rates Before and After Intervention

Comparison between the baseline and 3-month follow-up data in the cardiac rehabilitation group and the control group (see Table 4) demonstrated there was no significant difference regarding blood lipid level, but the hemoglobin A1cfraction in the cardiac rehabilitation group decreased significantly compared with the baseline data, and triglyceride level showed a decreasing trend in the cardiac rehabilitation group, but an increasing trend in the control group. Further analysis demonstrated that the lowdensity lipoprotein cholesterol control rate increased significantly in the cardiac rehabilitation group, but there was no change in the control group, and the systolic blood pressure control rate increased signifi -cantly in the cardiac rehabilitation group.

Table 1 Comparison of Baseline Data Between the Cardiac Rehabilitation Group and the Control Group Among Acute Coronary Syndrome Patients.

Comparison of Health Behavior Before and After Intervention

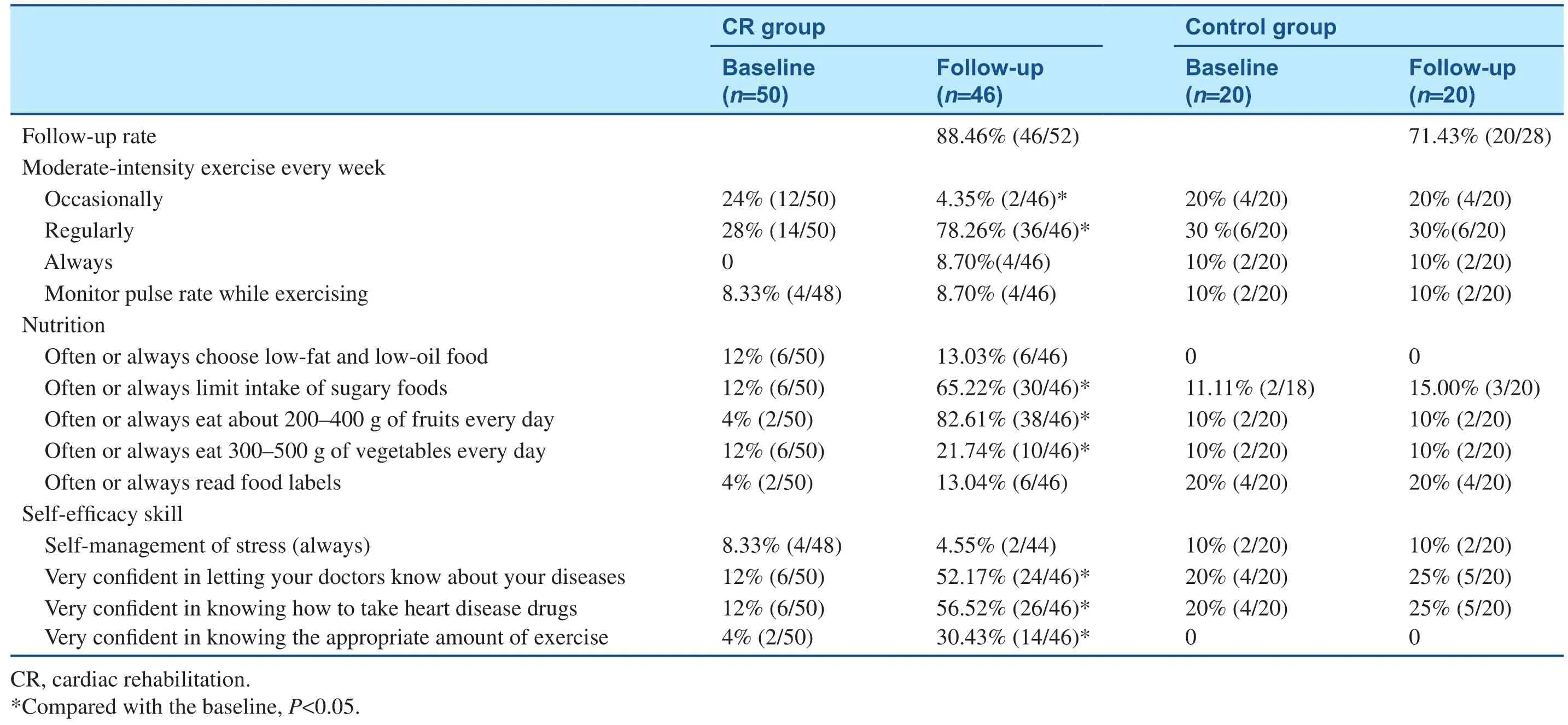

The proportion of “regular moderate intensity exercise per week” increased from 28% to 78.26%(P<0.05) in the cardiac rehabilitation group after 3 months of intervention, but no change was found in the control group.

According to the structural analysis of healthy diet (see Table 5), we also found that compared with before the intervention, the number of patients in the cardiac rehabilitation group who reported limiting intake of sugary foods (65.22% vs. 12%,P<0.05) and eating fruits (82.61% vs 4%,P<0.05)and vegetables (21.74% vs 12%,P<0.06) every day increased significantly, while there was no change in the control group. Regarding self-efficacy skill analysis, “skill of stress self-management” did not change among both groups, but the proportion of patients in the cardiac rehabilitation group who responded with “very confident” to the questions about “letting your doctors know about your diseases,” “knowing how to take heart disease drugs,”and “knowing the appropriate amount of exercise suitable for oneself” increased significantly, while there was no increase in the control group.

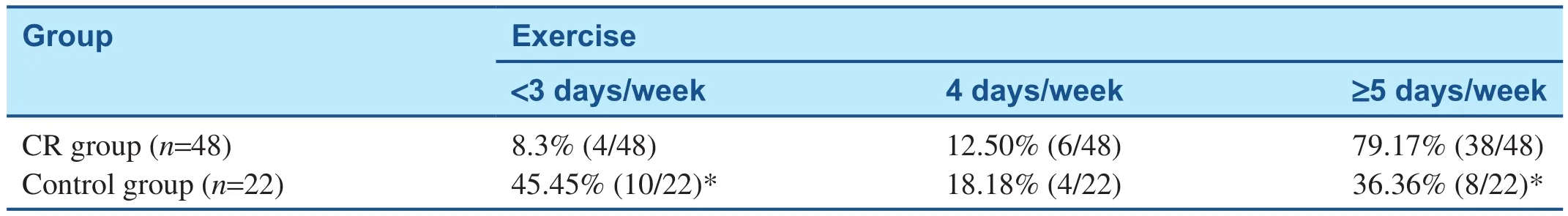

Exercise Rehabilitation Adherence and Safety

Among the patients in the cardiac rehabilitation group, 79.17% achieved the exercise target of “exercise 5 days/week, more than 30 min/day,” while only 36.36% of patients in the control group achieved the exercise target (see Table 6). No cardiovascular events during home exercise were reported in both groups.

Discussion

This is the first randomized study in China to test the effectiveness and safety of a home-basedcardiac rehabilitation program versus the usual care in a community setting. In this study we created a standardized home-based cardiac rehabilitation model including cardiac rehabilitation assessment,individualized treatment plan and three visits to the community clinic, a self-help heart manual, a home exercise video, a home-based exercise program and regular telephone contact for patients at home. Significant increases in exercise capacity,total cholesterol control rate, and systolic blood pressure control rate, reductions in hemoglobin A1cfraction, and improvements in exercise behavior and healthy diet were seen in the cardiac rehabilitation group at the 3-month follow-up. No significant differences were seen in or between groups in the levels of depression, anxiety, and quality of life. No adverse cardiac event–related exercise at home was reported in both groups.

Table 2 Comparison of Baseline Data Between All Patients and Patients Being Followed Up.

Cardiac rehabilitation has been considered the best way to prevent recurrent cardiovascular events,improve quality of life, and thereby reduce morbidity and mortality by coordinated, multifaceted intervention designed to optimize a cardiac patient’s physical, psychological, and social functioning[10]. The main approach to cardiac rehabilitation delivery in most countries is a supervised centerbased program, which usually occurs in a hospital. But for the low uptake rates (15–59%) [21, 22]and the low adherence rate for center-based programs (50% at 6 months) [23], recent studies have proved that alternative ways of providing cardiac rehabilitation increase participation [24]. Those studies performed in United Kingdom, the United States, Canada, etc., showed that a home-based cardiac rehabilitation program resulted in signifi-cantly greater increases in exercise capacity [25,26] and reductions systolic blood pressure [27] and lower anxiety [28] in the patients participating in home rehabilitation compared with the usual care at follow-up. Several randomized controlled trials comparing home-based with center-based cardiac rehabilitation also reported similar increases in exercise capacity and reductions in systolic blood pressure or serum cholesterol level at follow-up [25,26, 29–32]. The availability of a cardiac rehabilitation service in Chinese tertiary hospitals in a 2012 survey was only 24% [11], and this figure may be overestimated because of the very low response rate in that survey. The choice of a home-based cardiac rehabilitation intervention provides the opportunity to increase cardiac rehabilitation access and uptake for Chinese patients with CVD. But in China, few physicians recommend patients receive home-based cardiac rehabilitation intervention because of safety issues. Few physicians have the ability and knowledge to provide a home-based cardiac rehabilitation service, and no home-based cardiac rehabilitation service has existed in hospitals and the community until now. The development of an affordable,acceptable, and appropriate method of home-based cardiac rehabilitation is of significant importance[33]. To make home-based cardiac rehabilitation intervention in China replicable and of high quality, we created a standardized home-based cardiac rehabilitation program based on the American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation guidelines [10] and tested its efficacy and feasibility in our study. The results showed that this kind of standardized home-based cardiac rehabilitation intervention can increase exercise capacity, total cholesterol control rate, and systolic blood pressure control rate, improve exercise behavior and healthy diet, and reduce hemoglobin A1cfraction. No cardiac event related to home exercise was reported during the 3-month intervention, and this supported the conclusion of international clinical studies that home-based cardiac rehabilitation intervention is effective and safe.

Table 3Comparison of 6-min Walk Distance, Mental Status, and Quality of Life Before and After Intervention Between the Cardiac Rehabilitation Group and the Control GroupAmong Acute Coronary Syndrome Patients.

Currently in China, patients with ACS are regularly followed up by the cardiologist in a tertiary hospital clinic or by a community physician, specifically focused on medication but less concerned with medication adherence, health behavior, psychological status, diet, and exercise. Our study showed that the usual level of care cannot improve patients’ medication adherence, risk factor control,or healthy behavior or increase exercise capacity at the 3-month follow-up. This reminds us that it is urgent to change the health care model in China.

Comprehensive intervention should be the main difference between the cardiac rehabilitation service and the usual care. The quality of cardiac rehabilitation services directly related to cardiac rehabilitationbenefit, which has been highly strengthened by the American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation and British Association of Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation.Home-based programs should be comprehensive in nature (i.e., provide overall assessment, an individualized treatment plan, and educational and psychological support in addition to exercise training) and include health professional support such as regular telephone calls, particularly in the early stages of the programs. Compared with the home-based cardiac rehabilitation programs reported in previous studies, our program provided initial and followup cardiac rehabilitation assessment and individualized treatment plans, while previous studies did not provide such detailed information for cardiac rehabilitation intervention. From this point of view,the quality of the home-based cardiac rehabilitation service in our study can be considered the standard for home-based cardiac rehabilitation.

Table 4 Comparison of Blood Glucose Levels, Blood Lipid Levels, and Blood Pressure Control Rates Before and After Intervention Between the Cardiac Rehabilitation and the Control Group Among Acute Coronary Syndrome Patients.

A previous study of home-based cardiac rehabilitation consisting of a manual, home visits, and telephone contact reported significantly reduced hospital admissions during the first 6 months of follow-up compared with usual care [25]. The Heart Manual (West Lothian Health Care Trust, Scotland)is a facilitated home-based program for the first 6 weeks following myocardial infarction or revascularization and includes education, a home-based exercise program, and a tape-based relaxation and stress management program [25]. In our own homebased cardiac rehabilitation protocol, we used the idea of a heart manual and video, but we created a more generalized heart manual adapted to all CVD patients. The manual includes home exercise skills,medication information, nutritional skills, smoking cessation information, stress relaxation skills, and a diary, and we provided a home exercise video rather than stress management tapes. The main reason for replacing stress management tapes with a home exercise video was that Chinese patients are wary of exercising after they have received a diagnosis of ACS. Stress management cannot relive patients’fear of sudden death when they exercise. Since exercise has been considered to delay the development of atherosclerosis [34–36], and previous studies showed that exercise can relieve patients’depression and anxiety [37], we provided the home exercise video as exercise guidance at home. Our study showed that home-based cardiac rehabilitation with a heart manual and a home exercise video significantly improved patients’ exercise behavior at home and increased exercise capacity compared with the usual care.

Some previous studies examined the cost-effectiveness of cardiac rehabilitation for patients with myocardial infarction or heart failure, and suggested that home-based cardiac rehabilitation wasno different from center-based cardiac rehabilitation and that home-based programs were generally cost-saving compared with no cardiac rehabilitation[38]. But in one of the cost-minimization analyses,the cost to the government (taxation-based health care system) was greater with a home-based program than a center-based program, likely due to frequent home visits by hospital staff [39].T hose studies remind us that the cost-effectiveness of a home-based cardiac rehabilitation program depends heavily on its contents as well as patient profiles. The main cost of a home-based program is frequent home visits by case managers and physicians [39, 40–42]. Our study did not investigate the cost-effectiveness, but our home-based cardiac rehabilitation program used clinic visits rather than home visits, thus limiting the cost of home visits,and improved the availability of overall assessment and updated cardiac rehabilitation prescription by physicians in a clinical setting. So we can speculate on the basis of previous studies that the home-based cardiac rehabilitation program in our study should be cost-effective.

Table 5Comparison of Exercise, Diet, and Self-Efficacy Skill Before and After Intervention Between the Cardiac Rehabilitation Groupand the Control Group Among Acute Coronary Syndrome Patients.

Table 6 Comparison of Exercise Rehabilitation Adherence at 3-month Follow-Up Between the Cardiac Rehabilitation Group and the Control Group.

The limitation of this study included the small size, the short follow-up period, not all patients being followed up, and no cost-effectiveness analysis. The drop-out rate was 12.5%, and because of the small size, the results should be interpreted carefully. But the baseline characteristics of all the patients and patients being followed up were not different, so there are still some advantages. We created a standardized home-based cardiac rehabilitation intervention model in China and tested its efficacy and safety. This is the first randomized controlled study in China to investigate a home-based cardiac rehabilitation service compared with usual care in a community setting. Our study showed that a home-based cardiac rehabilitation service is a feasible, affordable, acceptable, and appropriate method to deliver a cardiac rehabilitation service in China, and provides the opportunity to increase cardiac rehabilitation access and uptake for Chinese patients with CVD.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the 12th Five-Year Science and Technology Support Program of the Ministry of Science and Technology of China(2013BAI06B02).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicting interests.

REFERENCES

1. Yang G, Wang Y, Zeng Y, Gao GF,Liang X, Zhou M, et al. Rapid health transition in China, 1990–2010: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 2013;381(9882):1987–2015.

2. WHO. 2005. Preventing chronic diseases: a vital investment.Accessed December 25, 2010,at http://www.who.int/chp/chronic_disease_report/en/.

3. Fox KA, Dabbous OH, Goldberg RJ, Pieper KS, Eagle KA, Van de Werf F, et al. Prediction of risk of death and myocardial infarction in the six months after presentation with acute coronary syndrome:prospective multinational observational study (GRACE). Br Med J 2006;333(7578):1091.

4. Boden WE, O’Rourke RA, Teo KK, Hartigan PM, Maron DJ,Kostuk WJ, et al. Optimal medical therapy with or without PCI for stable coronary disease. N Engl J Med 2007,356:1503–16.

5. Rezende PC, Hueb W, Garzillo CL, Lima EG, Hueb AC, Ramires JA, et al. Ten-year outcomes of patients randomized to surgery,angioplasty, or medical treatment for stable multivessel coronary disease: effect of age in the Medicine,Angioplasty, or Surgery Study II trial. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2013;146:1105–12.

6. Bjarnason-Wehrens B, McGee H,Zwisler A-D, Piepoli MF, Benzer W, Schmid J-P, et al. Cardiac rehabilitation in Europe: results from the European Cardiac Rehabilitation Inventory Survey. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil 2010;17:410–8.

7. The Writing Group for the Bypass Angioplasty Revascularization Investigation (BARI) Investigators. Five-year clinical and functional outcome comparing bypass surgery and angioplasty in patients with multivessel coronary disease. A multicenter randomized trial. J Am Med Assoc 1997;277(9):715–21.

8. Lane D, Carroll D, Ring C,Beevers DG, Lip GYH. Mortality and quality of life 12 months after myocardial infarction: effects of depression and anxiety. Psychosom Med 2001;63(2): 221–30.

9. Thorson AL. Sexual activity and the cardiac patient. Am J Geriatr Cardiol 2003;12(1):38–40.

10. Leon AS, Franklin BA, Costa F,Balady GJ, Berra KA, Stewart KJ, et al. Cardiac rehabilitation and secondary prevention of coronary heart disease. An American Heart Association scientific statement from the Council on Clinical Cardiology. Circulation 2005;111:369–76.

11. Zhang Z, Pack Q, Squires RW,Lopez-Jimenez F, Yu L, Thomas RJ. Availability and characteristics of cardiac rehabilitation programmes in China. Heart Asia 2016;8:9–12.

12. Suaya JA, Shepard DS, Normand SL, Ades PA, Prottas J, Stason WB. Use of cardiac rehabilitation by Medicare beneficiaries after myocardial infarction or coronary bypass surgery. Circulation 2007;116:1653–62.

13. Buttery AK, Carr-White G, Martin FC, Glaser K, Lowton K. Limited availability of cardiac rehabilitation for heart failure patients in the United Kingdom: findings from a national survey. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2014;21:928–40.

14. Korenfeld Y, Mendoza-Bastidas C, Saavedra L, Montero-Gómez A, Perez-Terzic C, Thomas RJ,et al. Current status of cardiac rehabilitation in Latin America and Caribbean. Am Heart J 2009;158:480–7.

15. McDonall J, Botti M, Redley B,Wood B. Patient participation in a cardiac rehabilitation program. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev 2013;33:185–8.

16. Tiller S, Leger-Caldwell L,O’Farrell P, Pipe AL, Mark AE.Cardiac rehabilitation: beginning at the bedside. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev 2013;33:186–8.

17. Cortes-Bergoderi M, Lopez-Jimenez F, Herdy AH, Zeballos C, Anchique C, Santibañez C,et al. Availability and characteristics of cardiovascular rehabilitation programs in South America.J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev 2013;33:180–41.

18. Chew DP, French J, Briffa TG, Hammett CJ, Ellis CJ,Ranasinghe I, et al. Acute coronary syndrome care across Australia and New Zealand: the SNAPSHOT ACS study. Med J Aust 2013;199:1–7.

19. Harlan III, WR, Sandler SA, Lee KL, Lam LC, Mark DB. Importance of baseline functional and socioeconomic factors for participation in cardiac rehabilitation. Am J Cardiol 1995;76:36–9.

20. Buckingham SA, Taylor RS,Jolly K, Zawada A, Dean SG,Cowie A, et al. Home-based versus center-based cardiac rehabilitation: abridged Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis. Openheart 2016;3:e000463.

21. Pell J, Pell A, Morrison C, Blatchford O, Dargie H. Retrospective study of in fluence of deprivation on uptake of cardiac rehabilitation. Br Med J 1996;313:267–8.

22. Gattiker H, Goins P, Dennis C.Current status and future directions. West J Med 1992;156:183–8.

23. Oldridge N. Compliance and exercise in primary and secondary prevention of coronary heart disease: a review. Prev Med 1982;11:56–70.

24. Lavie CJ, Arena R, Franklin BA.Cardiac rehabilitation and healthy life-style interventions: rectifying program deficiencies to improve patient outcomes. J Am Coll Cardiol 2016;67:13–15.

25. Bell J. A comparison of a multidisciplinary home based cardiac rehabilitation programme with comprehensive conventional rehabilitation in post-myocardial infarction patients. University of London 1998. PhD thesis.

26. Marchionni N, Fattirolli F,Fumagalli S, Oldridge N, Del Lungo F, Morosi L, et al. Improved exercise tolerance and quality of life with cardiac rehabilitation of older patients after myocardial infarction: results of a randomised,controlled trial. Circulation 2003;107:2201–6.

27. Haskell W, Alderman E, Fair J,Maron D, Mackey S, Superko H,et al. Effects of intensive multiple risk factor reduction on coronary atherosclerosis and clinical cardiac events in men and women with coronary artery disease (SCRIP).Circulation 1994;89:975–90.

28. Lewin B, Robertson I, Cay E, Irving J, Campbell M. Effects of self-help post-myocardial-infarction rehabilitation on psychological adjustment and use of health services. Lancet 1992;339:1036–40.

29. Carlson J, Johnson J, Franklin B,VanderLaan R. Program participation, exercise adherence, cardiovascular outcomes, and program cost of traditional versus modified cardiac rehabilitation. Am J Cardiol 2000;86:17–23.

30. DeBusk R, Haskell W, Miller N, Berra K, Taylor C, Berger W,et al. Medically directed at-home rehabilitation soon after clinically uncomplicated acute myocardial infarction: a new model for patient care. Am J Cardiol 1985;55:251–7.

31. Sparks K, Shaw D, Eddy D, Hanigosky P, Vantrese J.Alternatives for cardiac rehabilitation patients unable to return to a hospital-based program. Heart Lung 1993;22:298–303.

32. Arthur H, Smith K, Kodis J,McKelvie R. A controlled trial of hospital versus home-based exercise following coronary by-pass. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2002;34:1544–50.

33. O’Connor GT, Buring JE, Yusuf S, Goldhaber SZ, Olmstead EM,Paffenbarger RS, et al. An overview of randomized trials of rehabilitation with exercise after myocardial infarction. Circulation 1989;80(2):234–44.

34. Lenk K, Uhlemann M, Schuler G, Adams V. Role of endothelial progenitor cells in the benefi-cial effects of physical exercise on atherosclerosis and coronary artery disease. J Appl Physiol 2011;111(1):321–8.

35. Fleenor BS, Marshall KD, Durrant JR, Lesniewski LA, Seals DR.Arterial stiffening with ageing is associated with transforming growth factor-β1-related changes in adventitial collagen: reversal by aerobic exercise. J Physiol 2010;588(Pt 20):3971–82.

36. Momma H, Niu K, Kobayashi Y,Guan L, Sato M, Guo H, et al. Skin advanced glycation end product accumulation and muscle strength among adult men. Eur J Appl Physiol 2011;111(7):1545–52.

37. Lavie CJ, Milani RV. Adverse psychological and coronary risk pro fi les in young patients with coronary artery disease and benefits of formal cardiac rehabilitation. Arch Intern Med 2006;166:1878–83.

38. Wong WP, Feng J, Pwee KH,Lim J. A systematic review of economic evaluations of cardiac rehabilitation. BMC Health Serv Res 2012;12:243–8.

39. Jolly K, Lip GY, Taylor RS, Raftery J, Mant J, Lane D, et al. The Birmingham Rehabilitation Uptake Maximisation study (BRUM): a randomised controlled trial comparing home-based with centrebased cardiac rehabilitation. Heart 2009;95(1):36–42.

40. Collins L, Scuffham P, Gargett S.Cost-analysis of gym-based versus home-based cardiac rehabilitation programs. Aust Health Rev 2001;24(1):51–61.

41. Reid RD, Dafoe WA, Morrin L,Mayhew A, Papadakis S, Beaton L,et al. Impact of program duration and contact frequency on efficacy and cost of cardiac rehabilitation:results of a randomized trial. Am Heart J 2005;149(5):862–8.

42. Taylor RS, Watt A, Dalal HM, Evans PH, Campbell JL, Read KL, et al.Home-based cardiac rehabilitation versus hospital-based rehabilitation: a cost effectiveness analysis.Int J Cardiol 2007;119(2):196–201.

Cardiovascular Innovations and Applications2017年1期

Cardiovascular Innovations and Applications2017年1期

- Cardiovascular Innovations and Applications的其它文章

- Inherited Cardiomyopathies: Genetics and Clinical Genetic Testing

- The Role of Echocardiography in Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy

- Rationale and Design of the Randomized Controlled Trial of Intensive Versus Usual ECG Screening for Atrial Fibrillation in Elderly Chinese by an Automated ECG System in Community Health Centers in Shanghai(AF-CATCH)

- Clinical Utility of Amlodipine/Valsartan Fixed-Dose Combination in the Management of Hypertension in Chinese Patients

- Depression, Anxiety, and Cardiovascular Disease in Chinese: A Review for a Bigger Picture

- Catheter Ablation of Atrial Fibrillation:Where Are We?