Occlusive Spasm of the Left Anterior Descending Artery and First Diagonal Branch After Implantation of Everolimus Eluting Stents Without Re-stenosis in a Female Patient with Resting Angina

Giancarlo Pirozzolo, Anastasios Athanasiadis, Udo Sechtem and Peter Ong

1Robert-Bosch-Krankenhaus, Department of Cardiology, Stuttgart, Germany

Introduction

Myocardial ischemia and angina pectoris can be caused by various mechanisms such as coronary atherosclerosis, vasospasm or coronary microvascular dysfunction [1]. We here report a case of a 56-year-old female patient with a history of previous percutaneous coronary interventions (PCI)who reported repetitive attacks of resting angina.Coronary risk factors included hypertension, hypercholesterolemia (LDL = 97mg/dL on atorvastatin),ex-smoker (ceased 2013), and a positive family history (fatal myocardial infarction in father aged 52 years and brother 59 years).

Invasive Assessments

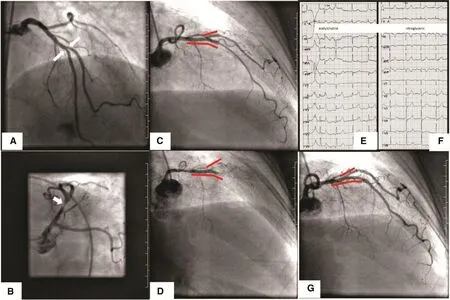

The patient underwent the first PCI in 2011 for a bifurcation stenosis of the left anterior descending artery (LAD)/ first diagonal branch (D1) with everolimus eluting stents (EES) at another hospital. One stent was placed in the LAD and another stent was placed as a T-stent in the D1 (Figure 1A).Three months later she was readmitted for recurrent resting angina and a high-grade stenosis proximal to the LAD stent was seen and stented with an EES(Figure 1B). The patient continued to have resting angina leading to two subsequent admissions at another hospital prompting coronary angiograms without progression of disease. In 2016, the patient was admitted to our hospital with another episode of severe resting angina without demonstrable ischemic ECG shifts or troponin elevation.Invasive angiography revealed no re-stenosis or de novo stenosis (Figure 1C). However, intracoronary acetylcholine provocation testing showed occlusive spasm of the LAD and D1 with concomitant ST-segment elevation at 100 µg acetylcholine(Figure 1D–E). The patient had full reproduction of her symptoms during the test. After intracoronary nitroglycerin injection, the abnormal findings disappeared (Figure 1F–G). The patient was discharged on high-dose diltiazem, bisoprolol was stopped. After 3 months her symptoms had markedly improved.

Discussion

Figure 1 (A) Coronary angiogram of the left coronary artery showing a bifurcation stenosis of the left anterior descending coronary artery and the first diagonal branch (white arrows). (B) Coronary angiogram of the left coronary artery after the initial stent implantations in the LAD/D1 showing a LAD stenosis proximal to the previously implanted LAD stent (white arrow). (C)Coronary angiogram of the left coronary artery at the most recent examination in 2016 showing patent LAD/D1 stents and no relevant LCA stenosis (the red bars mark the area of the implanted stents). (D) Coronary angiogram of the left coronary artery after intracoronary injection of 100 µg acetylcholine. There is occlusive spasm of the LAD and D1 within/distal to the stents(the red bars mark the area of the implanted stents). (E) 12-Lead ECG tracings after 100 µg of intracoronary acetylcholine injection showing ST-segment elevation in leads V2-V4 and aVL. The patient had full reproduction of her symptoms during the test. (F) 12-Lead ECG tracings after 200 µg of intracoronary nitroglycerin injection showing normalization of ST-segment changes. (G) Coronary angiogram of the left coronary artery after 200 µg of intracoronary nitroglycerin injection showing patent vessels and resolution of spasm.

Recurrent resting angina in a patient with previous PCI is challenging. Often a progression of atherosclerosis is suspected and repeated angiograms are performed. However, the latter frequently show no (re-)stenosis [2]. Investigations for other mechanisms of myocardial ischemia such as vasospasm are not yet part of clinical routine in many centers [3]. Yet, as shown in this case, coronary artery spasm represents an important cause of resting angina in such patients. Although intracoronary acetylcholine testing clearly showed occlusive spasm of the LAD and D1 the exact underlying type of spasm is debatable. It is possible that there was focal spasm at the site of the stents or at the borders between the LAD and the D1 stents. Another possibility is that there was diffuse occlusive spasm of the whole coronary tree distal to the stents and opacification of the vessels only stopped in the region of the stents. Finally, whether or not our patient already suffered from coronary spasm before the first stent implantation (questioning the appropriateness of PCI) or whether the tendency to spasm was influenced by the everolimus eluting stents remains an issue of discussion.

Conclusion

Patients with angina pectoris after successful PCI without re-stenosis should undergo investigations for coronary vasospasm (e.g. intracoronary acetylcholine testing). This may enable the treating physician to optimize pharmacological treatment and improve symptoms and prognosis.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

1. Crea F, Camici PG, Bairey Merz CN. Coronary microvascular dysfunction: an update. Eur Heart J 2014;35:1101–11.

2. Shah BR, Cowper PA, O’Brien SM, Jensen N, Drawz M, Patel MR,et al. Patterns of cardiac stress testing after revascularization in community practice. J Am Coll Cardiol 2010;56:1328–34.

3. Ong P, Athanasiadis A, Perne A, Mahrholdt H, Schäufele T,Hill S, et al. Coronary vasomotor abnormalities in patients with stable angina after successful stent implantation but without instent restenosis. Clin Res Cardiol 2014;103:11–9.

Cardiovascular Innovations and Applications2017年2期

Cardiovascular Innovations and Applications2017年2期

- Cardiovascular Innovations and Applications的其它文章

- Relationship Between Morning Hypertension and T-Peak to T-End Interval in Patients with Suspected Coronary Heart Disease

- Chronic Kidney Disease is a New Target of Cardiac Rehabilitation

- Evaluation of Multidisciplinary Collaborative Care in Patients with Acute Coronary Syndrome and Depression and/or Anxiety Disorders

- Role of Cholesterol Crystals During Acute Myocardial Infarction and Cerebrovascular Accident

- Digoxin and Heart Failure: Are We Clear Yet?

- Telemedicine: Its Importance in Cardiology Practice. Experience in Chile