Digoxin and Heart Failure: Are We Clear Yet?

Amit Gupta, MD, Melissa Dakkak, DO and Alan Miller, MD

1Cardiology Fellow, University of Florida, Jacksonville, FL, USA

2Internal Medicine Resident, University of Florida, Jacksonville, FL, USA

3Professor, Department of Cardiology, University of Florida, Jacksonville, FL, USA

Introduction

?

Digoxin, a sodium-potassium adenosine triphosphatase inhibitor, is the oldest drug still used in contemporary practice, and was finally approved by the US Food and Drug Administration in 1997.Coincidently, the Digitalis Investigation Group (DIG)trial data were released in the same year and showed no mortality benefit of digoxin. Since then digoxin use has decreased in the last decade. However, the DIG trial did show that in heart failure (HF) patients treated with digoxin there was a significant reduction in hospitalization and readmission rate [2].

Despite a better understanding of HF pathophysiology as well as advancements in pharmacotherapy,30-day readmission rates for acutely decompensated HF remain elevated. In the past 25 years, the annual number of hospitalizations has increased from 800,000 to more than 1 million for HF as a primary diagnosis and from 2.4 million to 3.6 million for HF as a primary or secondary diagnosis. Recent estimates suggest that almost one- fifth of Medicare beneficiaries with acutely decompensated HF discharged from a hospital are readmitted within 30 days [3]. Because of this problem, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services have instituted a financial disincentive for hospitals with excessive 30-day hospital readmission rates for HF. Given this financial impetus, it is imperative to explore all options capable of reducing hospitalizations and readmissions. Furthermore, the benefit of digoxin in HF secondary to right ventricular (RV) failure and HF with preserved ejection fraction (EF) has not been well studied. Thus, we aim to discuss the use of digoxin in the management of HF secondary to both RV failure and left ventricular (LV) failure.

Digoxin as a Neurohumoral Modulator

Digoxin is an inotropic agent that acts by inhibiting the sodium-potassium exchanger, thus increasing sodium concentration, which helps to drive calcium into the cell using the sodium-calcium exchanger.Increase in intracellular calcium concentration subsequently leads to increased myocardial contractility by acting on the actin-myosin complex. However,several studies have evaluated neurohumoral and autonomic effects of digoxin, which are currently deemed more important [4, 5]. In normal healthy volunteers, digoxin causes peripheral vasoconstriction [5] but appears to have sympathoinhibitory effects in HF patients depending on the severity of the disease [6] and on the dose used [7, 8].

There are several potential explanations for the neurohumoral effects of digitalis in HF [4, 5] but the observed improvement or normalization of impaired baroreceptor-mediated function appears to play an important role [9, 10]. Several possibilities to explain the latter have been suggested, including a direct receptor effect, an increase in blood pressure,and inhibition of excessive activation of the sodiumpotassium adenosine triphosphatase pump [4, 9].Digoxin may also have an effect in reducing the levels of renin, aldosterone [6], and norepinephrine [11].The effect of digoxin on heart rate is deemed to be mainly secondary to its enhancing parasympathetic activity along with a sympatholytic effect [6, 7, 9, 12].In recent years, evidence has emerged that digoxin exerts its inotropic effects mainly at higher doses; at lower doses there is little inotropic action but more pronounced neurohumoral effects are observed [8].

Clinical Trials of Digoxin in Left Ventricular Failure

The largest studies before the DIG trial to provide compelling evidence that digoxin improved hemodynamics and clinical status in ambulatory patients with reduced EF were the Prospective Randomized Study of Ventricular Failure and Efficacy of Digoxin (PROVED) and the Randomized Assessment of Digoxin on Inhibitors of Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme (RADIANCE)trials, both of which were digoxin withdrawal trials.

Digoxin Withdrawal Trials

The PROVED and RADIANCE trials tested the hypothesis that withdrawal of digoxin from background therapy in stable chronic systolic HF patients with EF of 35% or less and New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional class II or class III HF in the ambulatory setting will lead to clinical deterioration. Patients were randomized to receive placebo or continue with digoxin and background therapy for 12 weeks. Physicians were encouraged to maximize background therapy of diuretics or diuretics plus angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor (ACEI) respectively. In both trials patients receiving placebo demonstrated significant worsening of maximal exercise performance compared with those receiving digoxin. There was clearly a trend to worsening of most of the variables in the placebo group, whereas the digoxin group had reduced symptoms, reduction in NYHA class, increased exercise time, modestly increased LV EF (LVEF), increased cardiac output, and decreased HF hospitalization rates. Additionally,patients in whom digoxin therapy was withdrawn showed an increased incidence of treatment failures and a decreased time to treatment failure [13]. The RADIANCE trial in addition showed that patients in digoxin withdrawal arm also had increased LV end-systolic and end-diastolic dimensions as well as lower LVEF [14].

These studies concluded that, in addition to worsening clinical signs and symptoms of systolic HF on discontinuation of the use of digoxin, the use of an ACEI does not preclude the need for digoxin.However, the studies were criticized for removing digoxin from a stable medication regimen.Pooled retrospective analysis of PROVED and RADIANCE trial data also showed that digoxin as part of triple therapy with an ACEI and a diuretic led to the lowest incidence of worsening HF and lowered health care expenditure. However, mortality was not addressed in either study, which prompted further investigation [14].

Digoxin Investigation Group Trial

Following these results, the DIG trial was designed with the intention to determine the correlation between digoxin therapy and mortality. The trial enrolled 6800 patients in the ambulatory setting with EF of 45% or less in sinus rhythm irrespective of digoxin treatment status at enrollment. Patients were randomized in double-blind fashion to receive digoxin or placebo once daily in addition to background therapy. Most of the patients were elderly,with a mean age 65 years, white, male (80%), and with NYHA class II or class III HF, and 50% were using digoxin at the time of enrollment. Patients who were using digoxin before entry to the study were randomly assigned to receive either digoxin or placebo without a washout period. The digoxin dose in the trial was based on age, sex, and renal function but was left to physician discretion. More than 80% of patients randomized to receive digoxin were treated with dosages of 250 µg/day or greater.The patients were followed up for 28–58 months(mean 37 months).

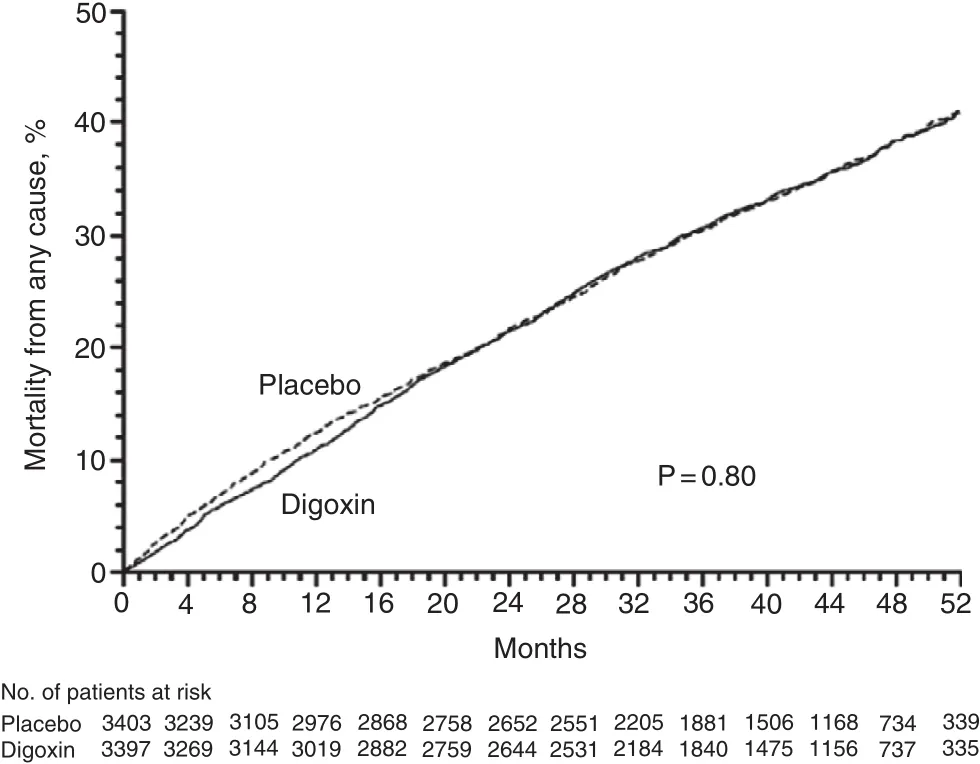

The primary end point of the trial was never reached as the digoxin group showed no significant difference in all-cause mortality compared with the placebo group but had a trend toward a lower risk of death attributable to worsening systolic HF (relative risk [RR] 0.88, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.77–1.01, P=0.06) (Figure 1). On the other hand, the risk of hospitalization, especially for worsening HF, was reduced with digoxin treatment (RR 0.75, 95% CI 0.69–0.82, P<0.001). When the combined outcome was analyzed, the incidence of death or hospitalization from worsening HF was markedly reduced.Furthermore, the DIG trial showed a reduction in the occurrence of either death or hospitalization due to worsening systolic HF at different LVEF,but was greatest in patients with an EF of 25% or lower, those who had dilated cardiomyopathies,and those in NYHA functional class III or class IV HF. Hospitalizations for digoxin toxicity were also twice as likely as compared with hospitalization for placebo; however, the incidence was low (67 events vs. 31 events, RR 2.17, 95% CI 1.42–3.32,P<0.001) [2].

Figure 1 Kaplan–Meier plot for mortality with digoxin versus placebo. (Reproduced with permission from Garg et al. [2].)

It is important point to note that more than 20%of patients in the placebo arm received open-label digoxin, which affected the mortality difference between the digoxin arm and the placebo arm.Also the serum digoxin concentration (SDC) considered therapeutic was between 0.5 and 2 ng/mL,which is considerably higher than current practice guidelines yet there was no excess mortality in the digoxin arm. The racial (<15% non-Caucasian) and sex makeup (<20% females) of trial participants also precludes generalization of the trial results to all patient populations.

Post Hoc Studies of the Digoxin Investigation Group Trial

Serum Digoxin Concentration and Mortality

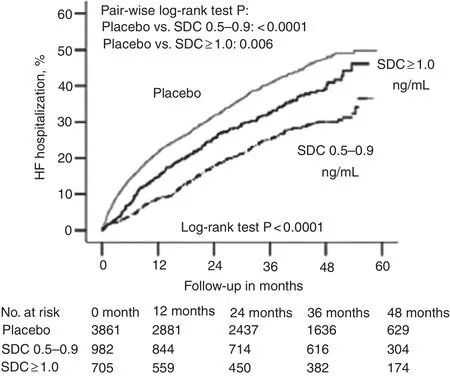

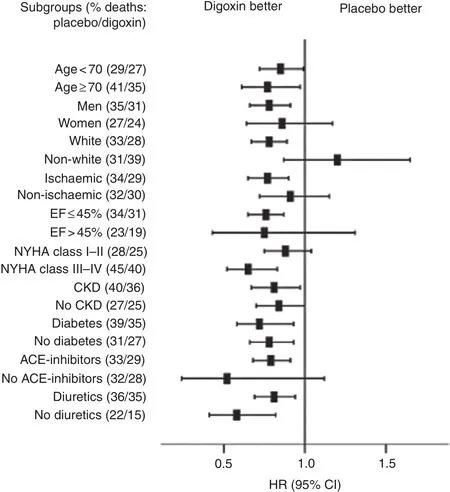

A comprehensive post hoc reanalysis of the DIG trial was performed by Ahmed et al. [15] to determine the effects of SDC in chronic HF with reduced EF and chronic HF with preserved EF. The analysis showed that digoxin reduces all-cause mortality and all-cause hospitalization at low serum concentration (0.5–0.9 ng/mL) compared with high serum concentration (≥1 ng/mL) and placebo (Figure 2).With further analysis of the subgroups, low SDC was associated with reduced mortality in most subgroups (Figure 3). However, there was no significant interaction between low SDC and EF of 45% or greater or sex. The conclusion of this post hoc analysis indicated that at low doses, digoxin reduces mortality and hospitalization in a broad spectrum of ambulatory patients with chronic HF with reduced EF and chronic HF with preserved EF, although the latter was not significant in the subgroup analysis.

Figure 2 Kaplan–Meier plot of cumulative risk of hospitalization due to worsening heart failure (HF) with serum digoxin concentration (SDC). (Reproduced with permission from Ahmed et al. [15].)

Figure 3 Hazard ratio (HR) and 95% confidence interval(CI) for various subgroups of heart failure patients for serum digoxin concentration of 0.5–0.9 ng/dL versus placebo. ACE,angiotensin-converting enzyme; CKD, chronic kidney disease;EF, ejection fraction; NYHA, New York Heart Association.

In another study by Ahmed et al. [16], the DIG trial database and the DIG ancillary study database were again analyzed, focusing on 4843 patients,982 receiving digoxin at low (0.5–0.9 ng/mL)serum concentration at 1 month, and 3861 receiving placebo and alive at 1 month. Propensity scores for low SDC, calculated with a nonparsimonious multivariable logistic regression model, were used to match 982 low-SDC patients with 982 placebo patients. Matched Cox regression analyses were used to determine the effect of digoxin at low serum concentration on outcomes. All-cause death occurred in 315 placebo patients and 288 low-SDC patients during 2940 and 3305 patient-years of follow-up respectively (hazard ratio [HR] 0.81, 95%,CI 0.68–0.98, P=0.028). Cardiovascular hospitalizations occurred in 493 placebo and 471 low-SDC patients during 2090 and 2399 patient-years of follow-up respectively (HR 0.82, 95% CI 0.70–0.95,P=0.010). Low-SDC compared with placebo for HF mortality and HF hospitalizations showed HRs of 0.65 (95% CI 0.45–0.92, P=0.015) and 0.63 (95%CI 0.52–0.77, P<0.0001) respectively. Ahmed et al.concluded that digoxin at low serum concentration significantly reduced mortality and hospitalizations in ambulatory patients with chronic HF with reduced EF and ambulatory patients with chronic HF with preserved EF.

Digoxin and Short-Term Mortality

In the DIG trial the median dosage of digoxin(0.25 mg/day) and the target SDC (0.8–2.5 ng/mL)were higher, which in part may explain the lack of long-term mortality benefit. To test this hypothesis,Ahmed et al. [17] examined the effect of digoxin on short-term outcomes in the DIG trial database;1-year all-cause death occurred in 392 and 448 patients in the digoxin and placebo groups respectively (HR 0.87, 95% CI 0.76–0.995, P=0.043). The respective HRs for cardiovascular and HF deaths were 0.87 (95% CI 0.76–1.01, P=0.072) and 0.66(95% CI 0.52–0.85, P=0.001). All-cause hospitalization occurred in 1411 and 1529 patients receiving digoxin and placebo respectively (HR 0.89, 95%CI 0.83–0.96, P=0.002). The respective HRs for cardiovascular and HF hospitalizations were 0.82(95% CI 0.75–0.89, P<0.0001) and 0.59 (95% CI 0.52–0.66, P<0.0001). Ahmed et al. concluded that digoxin reduced 1-year mortality and hospitalization in patients with chronic HF receiving ACEIs and diuretics.

Elderly Patients and Digoxin

On further analysis of another high risk group from the DIG trial, patients aged 65 years or older with HF and reduced EF in the digoxin group had a significantly lower 30-day all-cause hospital admission rate in the ambulatory setting. The effect of digoxin persisted for 60 as well as 90 days after randomization. Digoxin also reduced the composite end point of all-cause death or all-cause hospitalization at 30 days and all-cause hospitalization at 60 days and 90 days after randomization. The latter group also had lower risk of 30-day cardiovascular and HF hospitalizations, with similar trends for 30-day total mortality that did not reach statistical significance because of a low number of events [18]. This was further con firmed by a study by Rich et al. [19], who demonstrated that digoxin was associated with a risk reduction in HF death or hospitalization within each age category, including patients aged 80 years or older. They concluded that feared complications of digoxin including atrioventricular conduction delay, predisposition to supraventricular arrhythmias, and increased prevalence of gastrointestinal disturbances may be age related and less likely due to digoxin toxicity.

Women and Digoxin

In a post hoc analysis of the DIG trial data by Rathore et al. [20] there was an absolute difference of 5.8 percentage points in all-cause mortality between men and women receiving digoxin.Specifically women receiving digoxin had a 4.2 percentage points excess mortality compared than the placebo arm. In contrast, the rate of death in men assigned to digoxin was comparable with those who received placebo. However, in a retrospective analysis by Adams et al. [21], continuous multivariable analysis demonstrated a significant linear relationship between SDC and mortality in women(P=0.008) and men (P=0.002, P=0.766 for sex interaction). Averaging of HRs across serum concentrations from 0.5 to 0.9 ng/mL in women produced an HR for death of 0.8 (95% CI 0.62–1.13, P=0.245)and an NR for death or hospital stay for worsening HF of 0.73 (95% CI 0.58–0.93, P=0.011). In contrast, SDCs from 1.2 to 2.0 ng/mL were associated with an HR for death for women of 1.33 (95%CI 1.001–1.76, P=0.049). Hence they concluded digoxin had a beneficial effect on morbidity and no excess death risk in women at serum concentrations from 0.5 to 0.9 ng/mL, whereas a serum concentration of 1.2 ng/mL or higher seems harmful.

Digoxin in Renal Disease Patients

Digoxin is cleared by renal excretion, and the safety of digoxin in treating patients with HF with renal disease remains controversial. In the DIG trial post hoc analysis of patients for whom creatinine baseline and 12-month values were available (determined in a random sample,n=980), improvement in renal function defined as a 20% or greater increase in glomerular filtration rate (GFR) from randomization to 12 months was significantly more common in patients randomized to receive digoxin (odds ratio 1.5, P=0.02). This association persisted even after adjustment for baseline GFR and parameters associated with improvement in renal function. In patients with improved renal function, which occurred in 15.5% of the population studied [mean improvement in GFR of (34.5±15.4)%], randomization to digoxin therapy was associated with a substantially reduced incidence of death and hospitalization (adjusted HR 0.49, 95% CI 0.3–0.8, P=0.006,P for interaction 0.026) [22]. Since renal function is one of the most powerful prognostic factors for congestive HF outcomes as well as the impediment to adequate decongestion and use of evidence-based therapies, this aspect should be explored further in randomized clinical trials for confirmation.

There are only limited randomized data on appropriate dosing and safety of digoxin in hemodialysis patients. In a retrospective cohort study conducted in China including 67 HF patients receiving maintenance hemodialysis, 24 patients received intermittent low doses of digoxin, 23 patients received continuous low doses of digoxin, and the remaining patients were used as a control group without digoxin treatment. The inclusion criteria for this study were symptomatic HF with NYHA functional classification class II–IV HF, LVEF of 45% or less,normal sinus rhythm, and age 50 years or older.The exclusion criteria were mainly different types of cardiac arrhythmias. The patients returned for follow-up visits after 15, 30, and 60 days. Clinical and laboratory data of the patients were collected before digoxin therapy and at each follow-up visit.The brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) level and SDCs were measured by ELISA and the changes in LV end-diastolic diameter (LVEDD), LVEF, cardiac output, and heart rate were evaluated by two-dimensional echocardiography. The symptoms of digoxin toxicity were monitored in the treated patients.Compared with the control group, LVEDD, BNP level, and heart rate decreased significantly between day 0 and day 60 in the intermittent low-dose and continuous low-dose groups, with an increase in LVEF and cardiac output between day 0 and day 60 in the same groups (all P<0.05). The levels of BNP and the LVEDD, cardiac output, LVEF, and heart rate were not significantly different between these groups (P>0.05). Furthermore the mean SDC of the intermittent low-dose group was lower than that of the continuous low-dose group. No patients in the intermittent low-dose group had apparent symptoms of toxicity, but four patients in the continuous low-dose group developed digoxin toxicity.The study authors concluded that intermittent low digoxin dose is both safe and efficacious in hemodialysis patients [23].

Digoxin and Heart Failure with P reserved Ejection Fraction

There are only very limited studies of digoxin in HF with preserved EF. In the DIG ancillary trial,ambulatory chronic HF patients (N=988) with normal sinus rhythm and EF greater than 45% from the United States and Canada (1991–1993) were randomly assigned to receive digoxin (n=492) or placebo (n=496). During 37 months of mean follow-up, the primary combined outcome of HF hospitalization or HF death was experienced by 21%patients in the digoxin group and 24% patients in the placebo group (P=0.136). Digoxin had no effect on all-cause or cause-specific mortality, or all-cause or cardiovascular hospitalization. Use of digoxin was associated with a trend toward reduction in hospitalizations due to worsening HF (HR 0.79,95% CI 0.59–1.04, P=0.094) but also a trend toward increase in hospitalizations for unstable angina (HR 1.37, 95% CI 0.99–1.91, P=0.061). On exhaustive review of the digoxin literature, no data could be found to link digoxin to acute coronary syndrome [24]. However, an analysis of the ARIAM Andulacia Registry data from 2007 to 2012 including 244 patients receiving digoxin among 20,331 patients admitted for acute coronary syndrome in Spain showed digoxin had no significant influence on hospital prognosis [odds ratio 1.21, 95% CI 0.79–1.86] on multivariate analysis. The analysis of a propensity-matched cohort of 464 patients did not find differences in hospital mortality (13.4% vs.13.4%) or other complications. The study authors concluded that previous treatment with digoxin was not associated with an increase in dysrhythmic complications nor was it an independent predictor of mortality during hospitalization for acute coronary syndrome [25].

Meyer et al. [26] further analyzed the DIG trial data using propensity score matching to assemble a cohort of 916 pairs of patients with HF with reduced EF and patients with HF with preserved EF who were balanced in all measured baseline covariates. They estimated the HR and 95% CI of the effect of digoxin on outcomes separately of systolic HF patients and diastolic HF patients at 2 years (protocol prespecified) and at the end of 3.2 years of median follow-up. HF hospitalization or HF death occurred in 28% and 32% of systolic HF patients (HR 0.85, 95% CI 0.67–1.08, P=0.188) and 20% and 25% of diastolic HF patients (HR 0.79,95% CI 0.60–1.03, P=0.085) receiving digoxin and placebo respectively, thus already showing a trend toward benefit in HF with preserved EF. At 2 years, there was a clear benefit in the combined end point for both systolic HF patients (HR 0.72, 95%CI 0.55–0.95, P=0.022) and diastolic HF patients(HR 0.69, 95% CI 0.50–0.95, P=0.025) compared with patients who received placebo. Digoxin also reduced the 2-year HF hospitalization rate in both systolic HF patients (HR 0.73, 95% CI 0.54–0.97,P=0.033) and diastolic HF patients (HR 0.64, 95%CI 0.45–0.90, P=0.010) HF. Meyer et al. concluded,as in HF with reduced EF, digoxin was equally effective in reducing hospitalizations in patients with HF with preserved EF.

Digoxin and Right Ventricular Failure

Although extensive research has been performed on the effects of digoxin on LV failure, very little has been accomplished in terms of its benefit for patients with RV failure. The aim of this section is to determine the benefit of digoxin in RV failure secondary to primary pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) and secondary pulmonary hypertension(PH), most notably chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and HF due to LV dysfunction [27].

Right Ventricular Failure Secondary to Pulmonary Artery Hypertension

Chronic PH stimulates adaptive changes in the RV myocardium that help maintain RV stroke volume.It is the function of the right ventricle that correlates with the morbidity and death associated with PAH[27]. Furthermore, the degree of symptoms and survival in patients with idiopathic PAH are closely related to RV function. High mean right atrial pressures and low cardiac output have consistently been associated with poorer survival. In contrast, pulmonary arterial pressure has only a modest prognostic significance because its value is dependent on the degree of RV failure and thus may be decreased as RV failure progresses [28].

Chronic hypoxia is a major component in the development of PAH. The mechanism proposed for the development of PAH in the setting of hypoxia is the development of hypoxia-inducible factor 1(HIF-1)-dependent transactivation of genes controlling the intracellular calcium concentration in pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells (PASMCs).Digoxin has been shown to inhibit HIF-1 [29].Abud et al. [30] showed that treatment with digoxin attenuated the development of RV hypertrophy and prevented the pulmonary vascular remodeling and increased PASMC intracellular calcium concentration and pH and RV pressure in mice exposed to chronic hypoxia. When digoxin treatment started after PH was established, digoxin attenuated the hypoxia-induced increase in RV pressure and PASMC pH and intracellular calcium concentration.

Rich et al. [31] demonstrated a favorable hemodynamic effect of digoxin in patients with RV failure from severe PAH. There was an approximately 10% increase in resting cardiac output as well as a modest increase in mean pulmonary arterial pressure, which reflected an increase in cardiac output as heart rate remained the same and pulmonary vascular resistance was unaffected. They also observed a significant reduction in elevated circulating norepinephrine levels. Thus the neurohormonal benefits of digoxin are also apparent in the setting of RV failure secondary to PAH.

Similar findings were con firmed by Eshtehardi et al. [32], who performed a retrospective case-control study including all consecutive patients aged 18 years or older with diagnosed severe PH (de fined by a pulmonary arterial systolic pressure of 65 mmHg or greater, RV hypokinesis, and LVEF of 50% or greater) from three hospitals at Monte fiore Medical Center between 2002 and 2012. Patients were divided into two groups on the basis of whether or not they were receiving digoxin therapy for 12 consecutive months after diagnosis of PH. The primary end point was 1-year all-cause mortality and the secondary end point was 1-year hospital readmission.Of 2208 patients included (age 71±16 years; 31%male), 166 patients (8%) were receiving digoxin therapy. In the entire population, 1-year mortality was 32.6% and the readmission rate was 3.6%.Mortality was significantly lower in the digoxin group than in the no-digoxin group (25% vs. 33%,RR 0.67, 95% CI 0.49–0.92, P=0.02), while the readmission rate was not different (3.9% vs. 3.6%,RR 1.64, 95% CI 0.84–3.18, P not significant). In multivariate analysis adjusted for baseline characteristics, digoxin therapy remained an independent predictor of lower 1-year mortality (P<0.02).

Right Ventricular Failure Secondary to Cor Pulmonale

RV enlargement or hypertrophy secondary to pulmonary disease in the absence of LV failure is defined as cor pulmonale. COPD is the most common cause of cor pulmonale. In patients with COPD, pulmonary arterial pressure usually is only mildly elevated. The development of cor pulmonale is related to the severity of COPD and the degree of hypoxemia, a process known as hypoxemic pulmonary vasoconstriction. In a recent study,Burgess et al. [18] showed that RV end-diastolic diameter index and the velocity of late diastolic filling were independent predictors of survival. There are very limited data on the use of digoxin in type III PH secondary to COPD. Aubier et al. [33] found that in patients with COPD, digoxin did not produce any significant changes in measured hemodynamics. The limitations of that study included a sample size of only eight patients with COPD and evidence of RV failure as well as the measurement of changes in diaphragmatic contractility in place of myocardial contractility.

Brown et al. [34] investigated the effect of orally administered digoxin on RV EF (RVEF) at rest and during exercise in 12 patients with stable hemodynamics and chronic airway obstruction. The results showed an increase in RVEF at rest and with exercise as well as increases in exercise duration,maximum workload achieved, exercise capacity(Vo2max) and oxygen pulse, although they were not significant. However, the main criticism of that study is its small sample size.

However, according to Mathur et al. [35], after 8 weeks of digoxin therapy in patients with chronic bronchitis or emphysema, an increase in RVEF was observed only in those who had depressed LVEF as well. Digoxin therapy resulted in no change in RVEF when LVEF was preserved. In light of limited and conflicting studies, further trials with large sample sizes powered for significance need to be performed to adequately assess the benefit of digoxin in RV failure in the setting of PH secondary to COPD.

Digoxin and Mortality in Atrial Fibrillation

Vamos et al. [36] published a meta-analysis of studies regarding the effect of digoxin use on mortality in patients with atrial fibrillation (AF) or congestive HF reported in the English peer-reviewed literature in PubMed and the Cochrane trials database between 1993 and 2014. Nineteen reports were identified. Nine reports dealt with AF patients, seven with patients with congestive HF, and three with both clinical conditions. On the basis of the analysis of the adjusted mortality results of all 19 studies, comprising 326,426 patients, digoxin use was associated with an increased RR of all-cause death(HR 1.21, 95% CI 1.07–1.38, P<0.01). Compared with individuals not receiving glycosides, digoxin was associated with a 29% increased death risk (HR 1.29, 95% CI 1.21–1.39) in the subgroup of publications comprising 235,047 AF patients. Among 91,379 HF patients, digoxin-associated death risk increased by 14% (HR 1.14, 95% CI 1.06–1.22).

Ouyang et al. [37] reported similar findings in their meta-analysis of studies in PubMed and the Embase database examining the association between digoxin use and the death risk in AF. Eleven observational studies were identified that met the inclusion criteria, five of which additionally used propensity score matching for statistical adjustment. In total, 318,191 patients were followed up for a mean of 2.8 years.HR and 95% CI were calculated with the randomeffects model. Overall, digoxin use was associated with a 21% increased risk of death (HR 1.21, 95%CI 1.12–1.30). Sensitivity analyses found the results to be robust. In the propensity score–matched AF patients, digoxin use was associated with a 17%greater risk of death (HR 1.17, 95% CI 1.13–1.22).When the AF cohort was grouped into patients with and without HF, the use of digoxin was associated with an increase in mortality in patients with and without HF, and no significant heterogeneity was seen between the groups (P>0.10). In conclusion,the results suggest that digoxin use was associated with a greater risk for death in patients with AF,regardless of concomitant HF.

However, these analyses are likely affected by the fact that they predominantly include observational studies from the era when digoxin therapeutic levels were deemed to be between 1 and 2 ng/dL, which likely may have been detrimental and counterbalanced any clinical benefits. Also metaanalysis is always affected by confounding factors within each study, and even propensity matching cannot control for all possible confounders.Patients with AF who are prescribed digoxin in clinical practice usually develop hypotension with beta blocker or calcium channel blocker therapy and hence represent a sicker cohort of patients. So,whether it is the drug or the patient that leads to higher mortality in AF can be decided only by a rigorous randomized controlled trial. However,most current clinical data come from registries and subgroup analysis.

The Outcomes Registry for Better Informed Treatment of Atrial Fibrillation (ORBIT AF) investigators reported on longitudinal patterns of digoxin use and its association with a variety of outcomes in a prospective outpatient registry conducted at 174 US sites with enrollment from June 2010 to August 2011. Among 9619 patients with AF and serial follow-up every 6 months for up to 3 years, 2267 patients (23.6%) received digoxin at study enrollment, in 681 patients (7.1%) digoxin therapy was initiated during follow-up, and 6671 patients (69.4%)were never prescribed digoxin. After adjustment for other medications, heart rate was 72.9 beats per minute (bpm) among digoxin users and 71.5 bpm among nonusers (P<0.0001). Prevalent digoxin use at registry enrollment was not associated with subsequent onset of symptoms, hospitalization, or death(in patients with HF, adjusted HR for death 1.04;without HF, HR 1.22). Incident digoxin use during follow-up was not associated with subsequent death in patients with HF (propensity-adjusted HR 1.05),but was associated with subsequent death in those without HF (propensity-adjusted HR 1.99) [38].

Lee et al. [39] reported on the effect of digoxin treatment on the end points of HF or death, HF alone, death alone, and ventricular tachycardia or ventricular fibrillation in 1820 patients with mild HF (NYHA class I and class II), prolonged QRS duration (≥130 ms), and reduced LVEF (≤30%)enrolled in the Multicenter Automatic De fibrillator Implantation Trial–Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy (MADIT-CRT). They reported dioxin therapy was not associated with an increased or decreased risk of HF or death (HR 1.07, 95% CI 0.86–1.33, P=0.56).

Madelaire et al. [40] presented data on the safety and effectiveness of digoxin in patients with HF and AF at the European Society of Cardiology 2015 meeting on the basis of data from the Danish National Registry. The study outcomes were risk of all-cause death and hospital readmission due to HF and/or AF during a 5-year follow-up. They identified 70,263 patients who were discharged from the hospital with both HF and AF from 1996 to 2012. They excluded 48,598 patients who were not receiving a vitamin K antagonist (e.g., warfarin), were receiving antiarrhythmic therapy (e.g.,amiodarone), or did not survive until 30 days after discharge. This left 21,665 patients: about half(10,989 patients) were treated with digoxin and the other half (10,676 patients) were not. The researchers then matched 8078 digoxin-treated patients with 8078 control patients who were not taking digoxin on the basis of age, sex, year of inclusion in the study, comorbidities, CHA2DS2VASc score, medication, and HF severity. They classified the patients’HF severity on the basis of the dosage of loop diuretics, from 1 (mild HF, ≤40 mg diuretics per day)to 4 (severe HF, >160 mg diuretics per day). In the propensity-matched cohort, most patients were taking an ACEI or an angiotensin receptor blocker(69%) or a beta blocker (64%) and fewer patients were taking spironolactone (27%). In the 5-year follow-up, all-cause mortality was slightly lower in the digoxin group than in the control group: 5.4 deaths per 100 person-years (3342 deaths) versus 5.8 deaths per 100 person-years (3588 deaths).However, the rate of hospital readmission was similar in the digoxin-treated patients versus the control patients: 7.8 readmissions per 100 personyears (4795 readmissions) versus 7.8 readmissions per 100 person-years (4769 readmissions) respectively. Overall, patients who received digoxin had a lower risk of death (HR 0.89, 95% CI 0.85–0.93)during follow-up than control patients. The lower risk of death in digoxin-treated patients versus control patients was greater in patients with severer HF(HR 0.82, 95% CI 0.73–0.92).

Role of Digoxin in the Ivabradine Era

Castagno et al. [41] retrospectively studied the DIG trial database looking at the primary composite end point used in the Systolic Heart Failure Treatment with the IfInhibitor Ivabradine Trial (SHIFT) (i.e.cardiovascular death or hospital admission for worsening HF) and compared the effect of digoxin on this end point with that of ivabradine. Digoxin led to a highly significant 15% RR reduction in this composite outcome when compared with an 18% RR reduction in SHIFT (both P<0.001). HF hospitalization was reduced by 26% with ivabradine and by 28% with digoxin (both P<0.001).Further inspection of both trials showed a near equal effect in reducing hospital readmissions and other outcomes reported by the SHIFT investigators. However ivabradine treatment was on the background of beta blockers and ACEI agents but patients treated with digoxin only had ACEI agents as the background.

In the SHIFT trial the mean baseline heart rate was 80 bpm. Compared with placebo, ivabradine reduced heart rate by 11 bpm at 28 days and 9 bpm at 1 year, a greater reduction in heart rate than achieved with digoxin [42]. In the RADIANCE trial there was a 7-bpm increase in heart rate over 3 months from the baseline of 77 bpm after digoxin therapy withdrawal [13]. The Dutch Ibopamine Multicenter Trial (DIMT) investigators found that digoxin decreased heart rate from 78±7 bpm to 74±8 bpm [6].

In contrast to ivabradine, the addition of digoxin therapy to therapy with a beta blocker has not been studied in patients with systolic HF in sinus rhythm. As some of the heart rate–reducing action of digoxin is due to an antisympathetic effect, concomitant beta blockade may attenuate the bradycardic response to digoxin. However beta blockers may not completely eliminate the heart rate–lowering effect of digoxin as it is vagally mediated[7, 12]. In a small single-center single-blind study including 42 patients with coronary artery disease and diastolic HF receiving optimum medical therapy with ACEIs, beta blockers, and diuretics who were randomized to receive ivabradine or low-dose digoxin, patients who received digoxin did significantly better than patients who received ivabradine [43].

Digoxin Toxicity Incidence Trends in Heart Failure Patients

Haynes et al. [44] analyzed trends in digoxin toxicity and digoxin use from 1991 to 2004, using surveys from the National Center for Health Statistics and Medicaid data in the United States and The Health Improvement Network (THIN) database in the United Kingdom. There was a significant decline in digoxin toxicity hospitalizations in the United States and a decline in ambulatory digoxin toxicity in the United Kingdom. The study demonstrated a reduction in the use of digoxin in the United States,but found no change in digoxin use in the United Kingdom. Finally, the number of prescriptions written for at least 250 µg decreased in the both the United States and the United Kingdom. The public health burden of digoxin toxicity declined dramatically from 1991 to 2004 in the United Kingdom and the United States. In the DIG trial, which was conducted in similar time frame, digoxin toxicity was suspected in 11.9% of cases, leading to hospitalization in 2% of patients [2].

On the basis of unpublished data from the Premier database, Hauptman et al. [45] retrospectively identified patients in whom digoxin toxicity had been diagnosed and/or who received digoxin immune Fab (DIF) over a 5-year period (2007–2011). DIF was evaluated with use of treatment date, number of vials administered, and total cost. Clinical outcomes included length of stay, cost of hospitalization, and in-hospital mortality. Exploratory multivariate analyses were conducted to determine predictors of DIF use and effect on length of stay, with adjustment for patient characteristics and selection bias.They found digoxin toxicity diagnosis without DIF treatment accounted for 19,543 cases; 5004 patients received DIF, of whom 3086 had a diagnosis of toxicity. Most patients were older than 65 years (88%).The predictors of DIF use were urgent/emergent admission, hyperkalemia, arrhythmias, acute renal failure, and suicidal intent (odds ratios of 2.4, 3.6,2.1, and 3.7 respectively; P<0.0001 for all). To majority of patients (78%) DIF was administered on days 1–2 of hospitalization; 10% of patients received treatment after day 7. Surprisingly digoxin was still used after DIF administration in 14% of cases. Among patients who received DIF within 2 days of admission, there was no difference inhospital mortality or length of stay compared with patients not receiving DIF.

Similar findings were obtained by See et al. [46]for the rates at which digoxin toxicity occurred in different age groups. From comparison of the number of outpatient prescription visits versus the number of visits to emergency departments for digoxin toxicity, they found the rate of emergency department visits per 10,000 outpatient prescription visits in which toxicity was subsequently identified is highly age dependent. In the 40–69-year age group,the toxicity rate was 3.6 per 10,000 outpatient prescriptions, but in the 85 years or older age group,the rate was as high as 10.8 emergency department visits per 10,000 outpatient prescriptions written for digoxin.

They also reported there has not been much change in the likelihood of individuals presenting with digoxin toxicity, with the numbers and rates of emergency department visits from 2005 to 2006 versus 2009 to 2010 basically unchanged at about 5000 emergency department visits for 9.1 million outpatient prescription visits, which is much lower than historically feared.

Conclusion

Digoxin at a low serum concentration has been shown to be effective in reducing hospitalizations and mortality for chronic systolic HF and its continued use is safe at low serum concentrations in all populations,including elderly people and women, and at intermittent dosing in renal patients. On the other hand, the use of digoxin in HF due to RV failure and HF with preserved EF has been poorly examined. From review of smaller studies and post hoc analysis, digoxin seems to have a beneficial effect in HF with preserved EF as well as on RV function in primary and secondary PH. Meta-analysis studies show an adverse effect of digoxin on mortality in patients with AF which is not supported by prospective registry data, Randomized clinical trials are needed to clarify digoxin’s role.Digoxin seems to be a useful agent in HF patients of all types and should be considered when a patient is symptomatic even when receiving maximum tolerated guideline-directed therapy.

REFERENCES

1. Bruenn HG. Clinical notes on illness and death of President Franklin D Roosevelt. Ann Int Med 1970;72;579–91.

2. Garg R, Gorlin R, Smith T, Yusuf S. The effect of digoxin on mortality and morbidity in patients with heart failure. N Engl J Med 1997;336(8):525–53.

3. Kim SM, Han HR. Evidence-based strategies to reduce readmission in patients with heart failure. J Nurse Practitioners 2013;9(4): 224–32.

4. Gheorghiade M, Ferguson D.Digoxin: a neurohumoral modulator in heart failure? Circulation 1989;84:2181–6.

5. Mason DT, Braunwald E. Studies on digitalis: effects of ouabain on forearm vascular resistance and venous tone in normal subjects and patients with heart failure. J Clin Invest 1964;43:532–43.

6. Van Veldhuisen DJ, Man in‘t Veld AJ,Dunselman PHJM, Lok DJ, Dohmen HJ, Poortermans JC, et al. Double blind, placebo-controlled study of ibopamine and digoxin in patients with mild to moderate heart failure: results of the Dutch Ibopamine Multicenter Trial (DIMT). J Am Coll Cardiol 1993;22:1564–73.

7. Watanabe AM. Digitalis and the autonomic nervous system. J Am Coll Cardiol 1985;5(Suppl A):35A–42A.

8. Packer M. The development of positive inotropic agents for chronic heart failure: how have we gone astray? J Am Coll Cardiol 1993;22(Suppl A):119A–26A.

9. Ferguson DW, Berg WJ, Sanders JS, Roach PJ, Kempf JS, Kienzle MG. Sympathoinhibitory response to digitalis glycoside in heart failure patients. Direct evidence from sympathetic neural recordings.Circulation 1989;80:65–77.

10. Ferguson DW. Digitalis and neurohormonal abnormalities in heart failure and implications for therapy. Am J Cardiol 1992;69:24G–33G.

11. Ribner HS, Plucinski DA Hsieh AM, Bresnahan D, Molteni A,Askenazi J, et al. Acute effects of digoxin on total systemic vascular resistance in congestive heart failure due to dilated cardiomyopathy:hemodynamic-hormonal study. Am J Cardiol1985;56:896–904.

12. Kim YI, Noble RJ, Zipes DP.Dissociation of the inotropic effect of digitalis from its effect on atrioventricular conduction. Am J Cardiol 1975;36:459–67.

13. Uretsky BF, Young JB, Shahidi FE, Yellen LG, Harrison MC, Jolly MK. Randomized study assessing the effect of digoxin withdrawal in patients with mild to moderate chronic congestive heart failure:results of the PROVED trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 1993;22:955–62.

14. Packer M, Gheorghiade M, Young JB, Costantini PJ, Adams KF, Cody RJ, et al. Withdrawal of digoxin from patients with chronic heart failure treated with angiotensinconverting-enzyme inhibitors. N Engl J Med 1993;329:1–7.

15. Ahmed A, Gambassi G, Weaver M,Young JB, Wehrmacher WH, Rich MW, et al. Effects of discontinuation of digoxin versus continuation at low serum digoxin concentrations in chronic heart failure. Am J Cardiol. 2007;100(2):280–4.

16. Ahmed A, Pitt B, Rahimtoola SH,Waagstein F, White M, Love TE,et al. Effects of digoxin at low serum concentrations on mortality and hospitalization in heart failure: a propensity-matched study of the DIG trial. Int Cardiol 2008;123(2):138–46.

17. Digitalis Investigation Group1,Ahmed A, Waagstein F, Pitt B, White M, Zannad F, et al.Effectiveness of digoxin in reducing one-year mortality in chronic heart failure in the Digitalis Investigation Group trial. Am J Cardiol 2009;103(1):82–7.

18. Burgess MI, Mogulkoc N, Bright-Thomas RJ, Bishop P, Egan JJ, Ray SG. Comparison of echocardiographic markers of right ventricular function in determining prognosis in chronic pulmonary disease. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2002;15:633–639.

19. Rich MW, McSherry F,Williford WO, Yusuf S, Digitalis Investigation Group. Effect of age on mortality, hospitalizations and response to digoxin in patients with heart failure: the DIG study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2001;38(3):806–13.

20. Rathore SS, Wang Y, KrumHolz HM. Sex based differences in the effect of digoxin for the treatment of heart failure. N Engl J Med 2002;347(18):1403–11.

21. Adams J, Herbert P, Wendy A,O’Connor CM, Lee CR, Schwartz TA, et al. Relationship of serum digoxin concentration to mortality and morbidity in women in the Digitalis Investigation Group trial:a retrospective analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol 2005;46:497–504.

22. Testani JM, Brisco MA, Tang WH, Kimmel SE, Tiku-Owens A, For fia PR, et al. Potential effects of digoxin on long-term renal and clinical outcomes in chronic heart failure. J Card Fail 2013;19(5):295–302.

23. Li X, Ao X, Liu Q, Yang J, Peng W, Tang R, et al. Intermittent lowdose digoxin may be effective and safe in patients with chronic heart failure undergoing maintenance hemodialysis. Exp Ther Med 2014;8(6):1689–94.

24. Ahmed A, Rich MW, Fleg JL,Zile MR, Young JB, Kitzman DW, et al. Effects of digoxin on morbidity and mortality in diastolic heart failure: the ancillary Digitalis Investigation Group trial.Circulation 2006;114(5):397–403.

25. Garcia-Rubira JC, Calvo-Taracido M, Francisco-Aparicio F, Almendro-Delia M, Recio-Mayoral A, Reina Toral A, et al.The previous use of digoxin does not worsen early outcome of acute coronary syndromes: an analysis of the ARIAM Registry. Intern Emerg Med 201;9(7):759–65.

26. Meyer P, White M, Mujib M, Nozza A, Love TE, Aban I, et al. Digoxin and reduction of heart failure hospitalization in chronic systolic and diastolic heart failure. Am J Cardiol 2008;102(12):1681–6.

27. François H, Ramona D, Murphy DJ, Hunt SA. Right ventricular function in cardiovascular disease,part II. Pathophysiology, clinical importance, and management of right ventricular failure. Circulation 2008;117:1717–31.

28. Matthews JC, McLaughlin V.Acute right ventricular failure in the setting of acute pulmonary embolism or chronic pulmonary hypertension: a detailed review of the pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management. Current Cardiology Reviews 2008;4(1):49–59.

29. Zhang H, Qian DZ, Tan YS, Lee K, Gao P, Ren YR, et al. Digoxin and other cardiac glycosides inhibit HIF-1α synthesis and block tumor growth. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2008;105:19579–86.

30. Abuda EM, Maylora J, Undema C,Punjabi A, Zaiman AL, Myers AC,et al. Digoxin inhibits development of hypoxic pulmonary hypertension in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2012;109(4):1239–44

31. Rich S, Seidlitz M, Dodin E,Osimani D, Judd D, Genthner D, et al. The short-term effects of digoxin in patients with right ventricular dysfunction from pulmonary hypertension. Chest 1998;114:787–92.

32. Eshtehardi P, Mojadidi K,Khosraviani K, Pamerla M, Zolty R. Effect of digoxin on mortality in patients with isolated right ventricular dysfunction secondary to severe pulmonary hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014;63(12 Suppl):A750.

33. Aubier M, Murciano D, Viirès N, Lebargy F, Curran Y, Seta JP,et al. Effects of digoxin on diaphragmatic strength generation in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease during acute respiratory failure. Am Rev Respir Dis 1987;135(3):544–8.

34. Brown SE, Pakron FJ, Milne N,Linden GS, Stansbury DW, Fischer CE, et al. Effects of digoxin on exercise capacity and right ventricular function during exercise in chronic air flow obstruction. Chest 1984;85(2):187–91.

35. Mathur, P, Powles, P, Pugsley, S,McEwan MP, Campbell EJ. Effect of digoxin on right ventricular function in severe chronic airflow obstruction. Ann Intern Med 1981;95:283–8.

36. Vamos M, Erath JW, Hohnloser SH. Digoxin-associated mortality:a systematic review and metaanalysis of the literature. Eur Heart J 2015;36(28):1831–8.

37. Ouyang AJ, Lv YN, Zhong HL,Wen JH, Wei XH, Peng HW, et al.Meta- analysis of digoxin use and risk of mortality in patients with atrial fibrillation. Am J Cardiol 2015;115(7):901–6.

38. Allen LA, Fonarow GC, Simon DN,Thomas LE, Marzec LN, Pokorney SD, et al. Digoxin use and subsequent outcomes among patients in a contemporary atrial fibrillation cohort. J Am Coll Cardiol 2015;65(25):2691–8.

39. Lee AY, Kutyifa V, Ruwald MH,McNitt S, Polonsky B, Zareba W,et al. Digoxin therapy and associated clinical outcomes in the MADIT-CRT trial. Heart Rhythm 2015;12(9):2010–7.

40. Madelaire C, Schou M, Nelveg-Kristensen KE, Schmiegelow M, Torp-Pedersen C, Gustafsson F, Køber L, Gislason G. Use of digoxin and risk of death or readmission for heart failure and sinus rhythm: A nationwide propensity score matched study. Int J Cardiol.2016;221:944–50.

41. Castagno D, Petrie MC, Claggett B, McMurray J. Should we SHIFT our thinking about digoxin?Observations on ivabradine and heart rate reduction in heart failure.Eur Heart J 2012;33;1137–41.

42. Swedberg K, Komajda M, Böhm M, Borer JS, Ford I, Dubost-Brama A, et al. Ivabradine and outcomes in chronic heart failure (SHIFT): a randomised placebo-controlled study.Lancet 2010;376(9744):875–85.

43. Giuseppe C, Jerie P. Comparison between ivabradine and low-dose digoxin in the therapy of diastolic heart failure with preserved left ventricular systolic function. Clin Pract 2013;3(2):e29.

44. Haynes K, Heitjan D, Kanetsky P, Hennessy S. Declining public health burden of digoxin toxicity from 1991 to 2004. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2008;84(1):90–4.

45. Hauptman PJ, Blume SW, Lewis EF,Ward S. Digoxin toxicity and use of digoxin immune fab: insights from a national hospital database. JACC Heart Fail. 2016;4(5):357–64.

46. See I, Shehab N, Kegler SR, Laskar SR, Budnitz DS. Emergency department visits and hospitalizations for digoxin toxicity: United States, 2005 to 2010. Circ Heart Fail2014;7:28–34.

Cardiovascular Innovations and Applications2017年2期

Cardiovascular Innovations and Applications2017年2期

- Cardiovascular Innovations and Applications的其它文章

- Relationship Between Morning Hypertension and T-Peak to T-End Interval in Patients with Suspected Coronary Heart Disease

- Occlusive Spasm of the Left Anterior Descending Artery and First Diagonal Branch After Implantation of Everolimus Eluting Stents Without Re-stenosis in a Female Patient with Resting Angina

- Chronic Kidney Disease is a New Target of Cardiac Rehabilitation

- Evaluation of Multidisciplinary Collaborative Care in Patients with Acute Coronary Syndrome and Depression and/or Anxiety Disorders

- Role of Cholesterol Crystals During Acute Myocardial Infarction and Cerebrovascular Accident

- Telemedicine: Its Importance in Cardiology Practice. Experience in Chile