ACE抑制肽构效关系及其酶法制备的研究进展

林 凯,韩 雪,张兰威,2,*,谯 飞,程大友

(1.哈尔滨工业大学化工与化学学院,黑龙江 哈尔滨 150090;2.中国海洋大学食品科学与工程学院,山东 青岛 266003)

ACE抑制肽构效关系及其酶法制备的研究进展

林 凯1,韩 雪1,张兰威1,2,*,谯 飞1,程大友1

(1.哈尔滨工业大学化工与化学学院,黑龙江 哈尔滨 150090;2.中国海洋大学食品科学与工程学院,山东 青岛 266003)

高血压是一种全球性的公共健康问题。血管紧张素转换酶(angiotensin converting enzyme,ACE)作为一种二肽缩肽酶,通过肾素-血管紧张素系统和激肽释放酶-激肽系统(kallikrein-kinin system,KKS)对血压进行调节。近年来,已有许多从各种食源蛋白中获得ACE抑制肽的研究报道。相比于化学合成药物,食源性蛋白获得的ACE抑制肽在治疗高血压方面更具安全性和温和性。许多研究已经探讨了食源性降压肽的构效关系,尤其是多肽一级序列对活性的影响。目前,最常用于制备ACE抑制肽的方式是酶催化水解蛋白,包括使用单酶或复合酶对蛋白进行水解。本文将主要对ACE抑制肽构效关系和酶法制备ACE抑制肽的研究进展进行综述,以期为获得优良的ACE抑制肽产品提供理论指导。

血管紧张素转换酶抑制肽;降压机制;构效关系;酶法制备

高血压作为一种慢性疾病是导致许多疾病的诱因,如中风、心肌梗塞、心力衰竭、动脉瘤和晚期肾病等[1]。血管紧张素Ⅰ转换酶(angiotensin Ⅰ-converting enzyme,ACE,EC 3.4.15.1)在血压调节系统肾素-血管紧张素系统(renin-angiotensin system,RAS)和激肽释放酶-激肽系统(kallikrein-kinin system,KKS)中起着重要作用[2]。ACE能够催化血管紧张素-Ⅰ转变成致使血管收缩的血管紧张素Ⅱ,同时将具有使血管舒张作用的缓激肽失活,从而导致血压升高。因此,抑制ACE活性能够提高缓激肽的浓度并降低血管紧张素Ⅱ的产生,从而能够有效地降低血压并且预防和治疗高血压及其相关疾病[3-4]。目前,化学合成的ACE抑制药物在临床方面具有显著的降压效果,如卡托普利(半抑制浓度(50% inhibitory concentration,IC50)=23 nmol/L)、依那普利(IC50=1.2 nmol/L)和赖诺普利(IC50=1.2 nmol/L)[5]。但该类药物通常会导致味觉失调、咳嗽和皮疹等副作用[3]。因此寻找一种无毒性、天然的、经济可行的替代物成为了必然趋势。最早报道天然的ACE抑制肽是从蛇毒液中分离得到的[6]。大量研究表明,天然蛋白中富含各种功能肽,通过酶解法将生物活性多肽从蛋白体中水解释放已被广泛研究,其中ACE抑制肽的制备获得了广泛的关注[7]。目前,ACE抑制肽已从豌豆[8]、羽扇豆[9]、裙带菜[10]、大豆[11]、小球藻[12]和牦牛乳酪蛋白[13-14]等许多蛋白源中通过酶解作用分离纯化得到。本文将从ACE抑制肽的降压机制、构效关系及酶法制备ACE抑制肽的方法方面进行讨论综述。

1 ACE概述

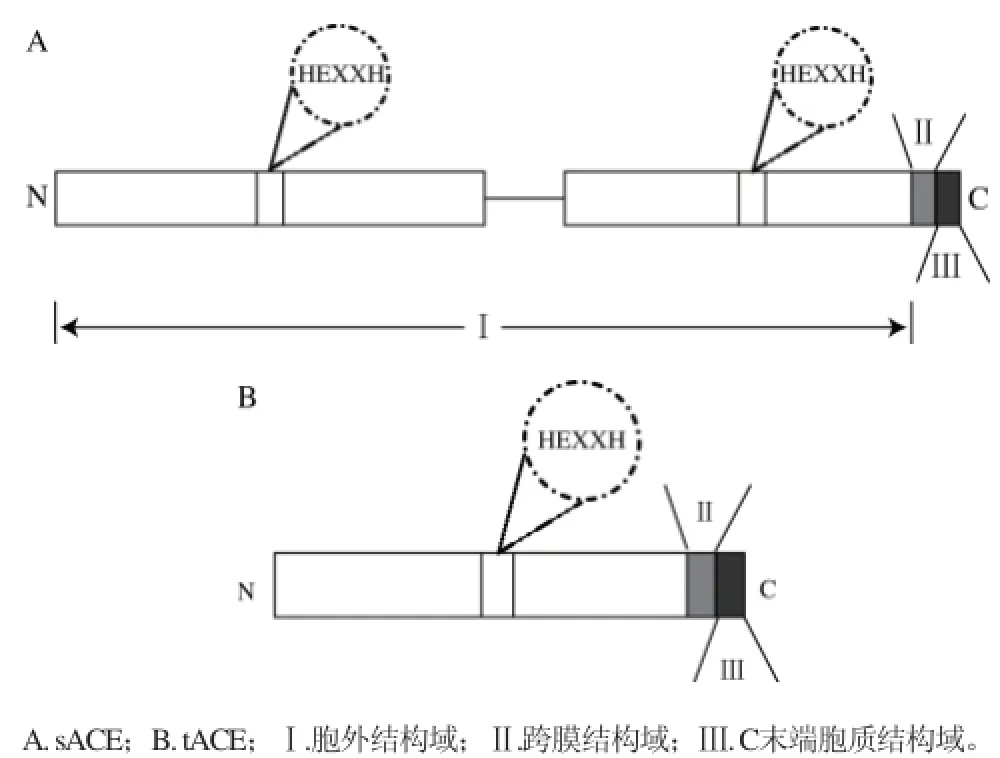

人体中含有两种ACE:体细胞ACE(somatic ACE,sACE)[15]和睾丸细胞ACE(testis ACE,tACE)[16-17],其均为同一基因编码,长度为21 kb,含有26 个外显子和25 个内含子。较长的sACE由1~12号和14~26号外显子翻译表达,较短的tACE由13~26号外显子翻译表达[18]。sACE是一种单分子结构的膜结合糖蛋白,由1 306 个氨基酸残基组成,其分为4 个特征区域,分别为信号肽(甲硫氨酸(methionine,Met)1~丙氨酸(alanine,Ala)29)、功能域(亮氨酸(leucine,Leu)30~精氨酸(arginine,Arg)1256)、跨膜结构(缬氨酸(valine,Val)1257~丝氨酸(serine,Ser)1277)、胞内区(谷氨酰胺(glutamine,Gln)1278~Ser1306)[19],功能域又分割成两个同源结构域,分别含有612个和600个氨基酸残基,两个同源结构域通过15个氨基酸序列连接。每个同源结构域均含有Zn2+结合模体HEXXH(H代表组氨酸(histidine,His);E代表谷氨酸(glutamate,G l u),X代表任意氨基酸残基)催化活性位点(图1),其中His、Gln和一分子H2O形成四面体配位结构与Zn2+配位[20]。尽管两个催化位点都具有催化水解血管紧张素-Ⅰ和缓激肽的功能,但是似乎只有C端结构域在调节血压方面起作用,研究也证明C端结构域是主要的血管紧张素-Ⅰ的催化位点[21]。具有功能活性的sACE的天然构象是以螺旋结构为其优势构象,立体结构中含有61个α螺旋、17个β折叠和14个β转角,在半胱氨酸(cysteine,Cys)157~Cys165、Cys757~Cys763、Cys957~Cys975、Cys1143~Cys1155处含有4个二硫键维持空间构型稳定,其3D结构如图2所示。同样,tACE是一种低分子质量膜结合糖蛋白,含有732个氨基酸残基,除N端的36个氨基酸残基是其特有之外,其余与sACE的C末端右半部分结构相同[22]。

图1 sACE和tACE一级结构示意图[[2233]]Fig.1 Schematic representation for the primary structure of sACE and tACE[23]

图2 人ACE晶体结构[[1199]]Fig.2 Crystal structure of human ACE[19]

2 ACE抑制肽降压机制

ACE是一种二肽羧肽酶,属于锌金属蛋白酶,需要锌离子和氯离子维持其活性[24]。ACE在RAS和KKS中起着重要作用,其中RAS为升压系统,KKS为降压系统,二者在血压调节方面互为拮抗体系。ACE能将RAS中由肾素分解释放出的无活性十肽——血管紧张素-Ⅰ的C末端的二肽(His-Leu),切除生成具有使血管收缩功能的血管紧张素-Ⅱ,致使血管平滑肌收缩。同时,促进醛固酮的分泌并导致水钠滞留,从而引起血压迅速升高[25]。降压系统KKS中舒缓肽能够增加前列腺素和NO的生成,导致血管舒张并降低外周血管阻力从而降低血压[26]。然而ACE能够切除KKS中缓激肽C末端的二肽(苯丙氨酸(phenylalanine,Phe)-Arg)使其失活[27],导致该系统处于抑制状态。综合这两者的作用致使血压迅速升高[28]。ACE作用机制如图3所示。

图3 ACE在RAS和KKS中的调节Fig.3 Regulatory function of ACE in the RAS and KKS

因此如果能够抑制ACE的活性,就能够实现降压效果。不同抑制肽的结构会导致不同的ACE抑制类型。研究表明大多数ACE抑制肽属于竞争性抑制[29],其能够与ACE活性位点结合以阻止底物与其结合。但也有研究发现ACE抑制肽为非竞争性抑制[30-31],其与底物结合位点之外的结合位点相结合,形成酶-抑制剂复合物,从而导致ACE构象改变,阻止其催化生成血管紧张素-Ⅱ[32]。通过以上两种抑制形式抑制ACE活性,从而降低血压。

3 ACE抑制肽构效关系

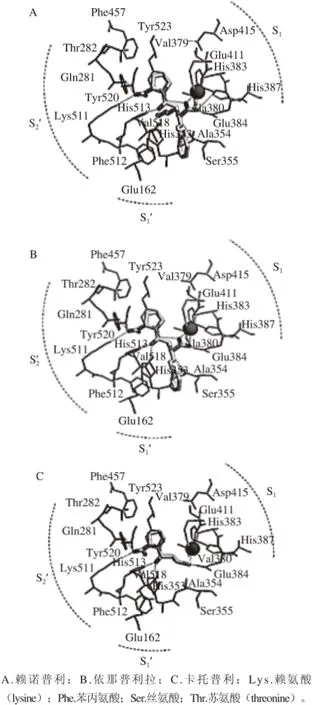

图4 ACE-赖诺普利、依那普利拉、卡托普利-酶复合物活性位点结合示意图[44][44]Fig.4 Schematic of ACE active sites in the form of enzyme-lisinopril, enalaprilat and captopril complexes[44]

sACE多肽链由接头片段链接两个金属肽酶结构域,分别是C端结构域和N端结构域,这两个结构域除了在多糖含量[33]和所需氯离子的最大激活浓度[34]不同外,展现了高度的序列相似性及相同的空间构象。ACE的C端活性位点呈现凹槽结构并在末端具有“帽子”结构,用于盖住活性位点通道[35]。其结构域催化部位含有3 个催化活性位点,分别为S1、S1’和S2’,这些催化位点均具有明显的疏水性,图4为ACE与3 种典型ACE抑制药物赖诺普利、依那普利拉和卡托普利活性位点结合示意图。由于ACE的C端结构域是疏水性环境,所以抑制肽中疏水性氨基酸的含量,决定了其是否具有较高的ACE抑制活性[36],并且S1、S1’和S2’具有其各自的亲和残基,所以抑制肽的活性很大程度上依赖于其C末端的倒数3 个氨基酸残基的种类。研究表明,当ACE抑制肽C末端倒数3 个氨基酸残基中含有色氨酸(tryptophan,Trp)、Tyr、Phe和Pro时,该抑制肽具有较高的ACE抑制活性[37]。除此之外,在具有ACE抑制活性的肽的N末端也经常发现含有Ile和Val[38]。更精确的构效关系研究发现,当C末端倒数第二个氨基酸为脂肪族氨基酸(如Val、Ile、Ala)、碱性和芳香族氨基酸(如Tyr、Phe)时[39],或C末端氨基酸为芳香族氨基酸(Trp、Tyr、Phe)、脂肪族氨基酸(Ile、Ala、Leu、Met)时[40]多肽更具ACE抑制活性。然而研究也发现当C末端倒数第二个氨基酸为Pro或C末端氨基酸为Glu时却很大程度上降低了肽的ACE抑制活性[41]。Wu Jianping等[42]通过对制备的二肽和三肽考察了其ACE抑制活性,验证了对于二肽结构中当氨基酸残基带有芳香环并且侧链具有疏水性时,如含有Phe、Tyr和Trp时具有较高的抑制活性。对于三肽,最有效的抑制结构是C末端为芳香族氨基酸残基,中间为带正电荷氨基酸残基,N末端为疏水性氨基酸残基。同时,对于3 个结构域均有各自专一亲和的氨基酸残基,如S1亲和芳香族氨基酸和Pro,S1’亲和Ala、Val和Leu,S2’亲和Ile[43]。

4 酶法制备ACE抑制肽

由于多肽序列整合在蛋白质分子中不具有生物活性,然而经酶催化水解作用使其释放出来后,这些多肽即能展现其特异的生物活性[45]。目前,制备生物活性肽最常用的方法是蛋白酶催化水解原料蛋白质,其优点在于反应条件温和、绿色安全、水解程度可控和能够制备特定生物活性肽等优点[7]。在水解过程中,蛋白酶按其特异的酶切位点将蛋白质分子酶切形成不同长短和序列的多肽,并且形成各异的功能特性。酶法水解蛋白制备ACE抑制肽可以使用单一酶或复合酶作用蛋白,其中利用复合酶水解蛋白可采用顺序加入或同时加入的方式进行水解[46]。

4.1 单酶水解制备ACE抑制肽

目前,常用于水解蛋白制备ACE抑制肽的酶有胰蛋白酶(EC 3.4.21.4)、胰凝乳蛋白酶(EC 3.4.21.1)、蛋白酶K(EC 3.4.21.64)、木瓜蛋白酶(EC 3.4.22.2)、碱性蛋白酶(3.4.21.62)、胃蛋白酶(3.4.23.1)和嗜热菌蛋白酶(EC 3.4.24.27)等[47]。由于每种蛋白酶具有其特异的酶切位点,因此根据ACE抑制肽分子结构特点选择合适的酶进行蛋白水解,能够更有效地获得ACE抑制肽。

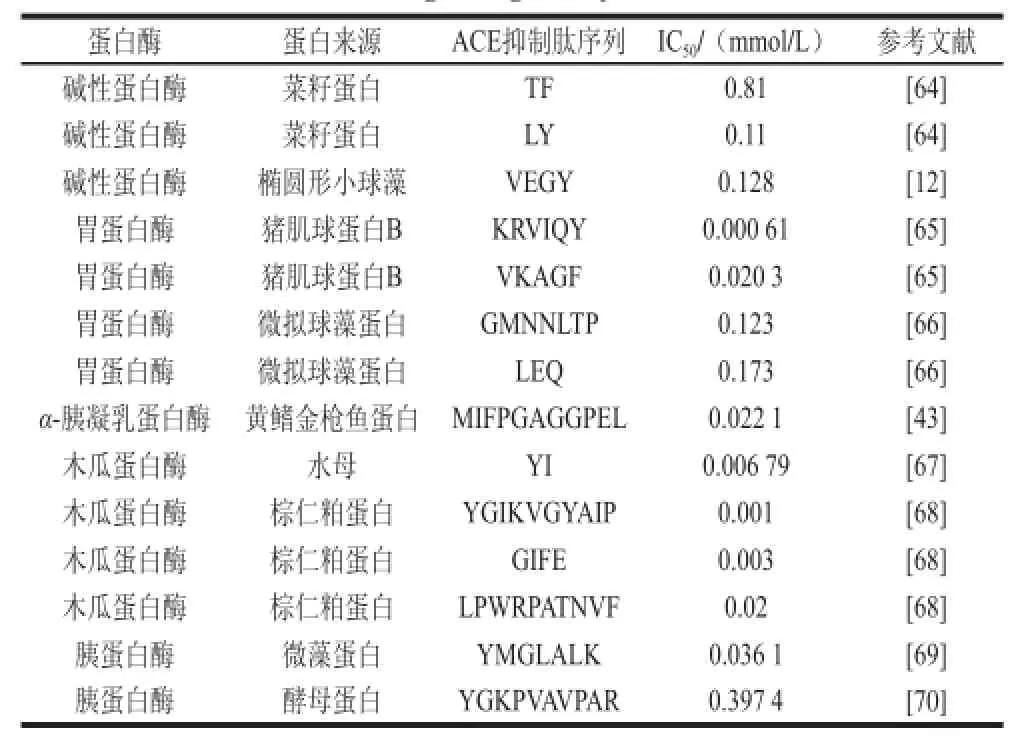

Mao Xueying等[13]利用碱性蛋白酶水解牦牛奶酪蛋白制备了ACE抑制肽,研究发现在水解4 h时,水解物具有最高的ACE抑制活性。对该组分进行10 kD和6 kD超滤处理后发现,具有高ACE抑制活性物质集中在低于6 kD水解物中,对其进行分离纯化测序后发现两条新的ACE抑制肽,分别为PPEIN和PLPLL,IC50值分别为(0.29±0.01)mg/mL和(0.25±0.01)mg/mL。构效关系研究认为,当多肽C末端为疏水性氨基酸时能够有效提高其与ACE的结合和抑制活性,PLPLL多肽符合这一结构特征。但对于仍具有较高ACE抑制活性的PPEIN并不具有该结构特征。但Gobbetti等[48]的研究可以解释这一结果,研究发现酪蛋白源的多肽中疏水性氨基酸占比大于60%时,该多肽即具有较高的抑制活性。目前已有许多利用碱性蛋白酶水解食源性蛋白获得生物活性肽的报道[49-51]。碱性蛋白酶属于丝氨酸S8胞内蛋白酶族,其有广泛的特异性酶切位点,能够对Phe、Leu、Trp和Tyr链接肽键的C末端进行酶切[52]。由于碱性蛋白酶特有的酶切特性,其酶解产生的肽C末端常带有疏水性氨基酸,这种结构符合具有高ACE抑制活性肽的特点。同时蛋白的水解程度也是影响多肽是否具有高ACE抑制活性的重要因素[53],研究发现碱性蛋白酶能够获得较短的肽段,而相较与长肽,短肽更具有潜在的ACE抑制活性[54]。同时研究发现,经碱性蛋白酶水解获得的ACE抑制肽具有抗肠胃酶消化的特性,能够被小肠直接吸收,在体内展现ACE抑制活性从而有效治疗高血压[55]。di Bernardini等[56]利用木瓜蛋白酶水解牛胸肉肌质蛋白,37 ℃条件下水解24 h后,发现经3 kD超滤渗透液的ACE抑制率达40.64%(蛋白质量浓度为1.48 mg/mL),远高于未经超滤处理的水解液的ACE抑制率49.82%(蛋白质量浓度为12.68 mg/mL)。通过质谱分析在小于3 kD的水解液中鉴定出6种多肽。根据构效关系分析这6种多肽可知,INDPFIDLHYM和RGDLGIEIPAEKVF的C末端具有碱性氨基酸Met和Phe;INPNSLFDIQVK和RGDLGIEIPAEKVF在C末端倒数第二个氨基酸均具有Val;GGWQMEEADDWLR和GWQMEEADDWLR在末端位置含有Leu,这些结构特点均使得3 kD的透过液具有较高的ACE抑制活性。Li Huan等[57]也利用木瓜蛋白酶对豌豆蛋白进行水解,同样获得了较高ACE抑制活性的多肽。木瓜蛋白酶也是被经常用作水解蛋白生产ACE抑制肽的一种蛋白酶,其具有广泛的特异性酶切位点,例如Leu和Gly等碱性氨基酸,这些碱性氨基酸具有疏水性侧链,能够有效促进具有ACE抑制肽的产生[55]。WuShangguang等[58]使用中性蛋白酶水解蜥鱼肌肉蛋白,通过一系列纯化方式得到了RVCLP多肽,其IC50值为175 μmol/L。该多肽C末端的疏水性氨基酸Pro是使其具有较高ACE抑制活性的重要原因。目前,已有利用胰蛋白酶水解酪蛋白生产出具有ACE抑制活性的十二肽,并已将其作为降压功能食品添加剂[59]。胰蛋白酶的特异性酶切位点主要倾向于碱性氨基酸,同时在C末端也会产生带正点氨基酸肽段,这两者均增加了其ACE抑制活性[60]。因此利用蛋白酶水解蛋白制备ACE抑制肽时,需要考虑酶的特异性酶切位点和其酶切活性。He Rong等[61]利用蛋白酶水解油菜籽蛋白制备ACE抑制肽时发现,使用碱性蛋白酶、嗜热菌蛋白酶和蛋白酶K相较于风味蛋白酶能有产生更多低分子质量肽段,主要是由于这3 种酶具有更高的内切酶活性,同时获得的小分子肽也使得其具有更高的ACE抑制活性。近年来,也有使用嗜热菌蛋白酶[62]、胰凝乳蛋白酶[55]和胃蛋白酶[63]水解蛋白制备ACE抑制肽的报道。这些蛋白酶均能水解产生较高ACE抑制活性的多肽,主要的共同点也是能够在多肽C末端特异性酶切产生疏水性氨基酸或者芳香族氨基酸,而根据具有ACE抑制活性的肽结构分析,这些C末端氨基酸能够有效提高ACE抑制肽抑制活性。因此在利用蛋白酶进行水解蛋白制备ACE抑制肽时,根据具有高活性ACE抑制肽的结构特点考查蛋白酶的特异性酶切位点和酶切活性,能够有效提高ACE抑制肽的制备。表1列举近年来了利用单酶水解不同蛋白源制备ACE抑制肽的研究,从已得到的ACE抑制肽序列可以发现,在C端序列中均含有疏水性氨基酸,其可以与疏水性的ACE催化活性位点更具亲和性,从而具有ACE抑制活性。

表1 单酶水解不同蛋白源制备的ACE抑制肽Table1 Preparation of ACE peptides derived from different proteins using a single enzyme

4.2 复合酶水解制备ACE抑制肽

单酶水解蛋白制备ACE抑制肽时,由于酶所固有的酶切位点而使其获得的ACE抑制肽具有一定的局限性。目前,已有采用两种或两种以上的蛋白酶顺次或同时水解蛋白制备ACE抑制肽的研究。由于各种蛋白酶具有不同的酶切位点,多种酶对蛋白进行复合水解可以进行互补切割,从而得到单一酶无法获得的新型ACE抑制肽。

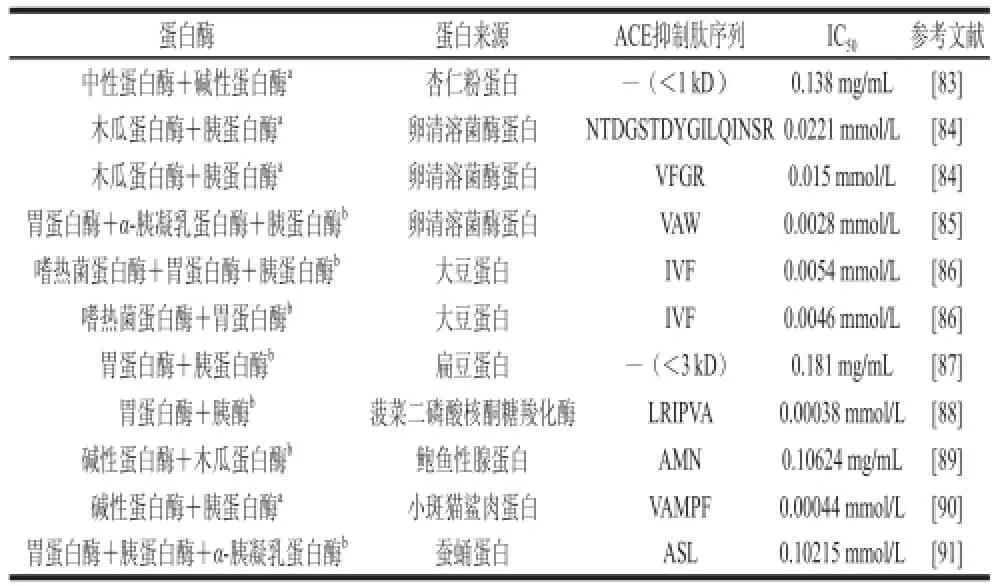

Yamada等[71]使用了碱性蛋白酶+中性蛋白酶+胰蛋白酶同时加入的方式水解牛乳酪蛋白制备ACE抑制肽。体外实验发现该复合酶水解物ACE抑制活性IC50值为74 μg/mL,同时该水解物利用灌胃原发性高血压鼠(spontaneously hypertensive rats,SHRs)进行体内实验,发现连续28 d灌胃使得SHRs收缩压(systolic bloodpressure,SBP)增长速率降低。对该水解物进行了纯化分离,获得了αs2-酪蛋白源的新型三肽MKP,其IC50值为0.12 μg/mL。体内实验发现,MKP可以瞬时明显降低SHRs的SBP,具有良好的降压活性。对于该三肽MKP结构分析可知,其N端和C端为疏水性氨基酸Met和Pro,中间为带正电荷氨基酸Lys,因此该三肽能够易于与ACE结合,从而具备良好的ACE抑制活性。Li Peng等[72]使用胃蛋白酶和胰蛋白酶顺序水解的方式对开心果提取蛋白进行了水解,并分离纯化得到具有较高ACE抑制活性的五肽ACKEP(IC50=126 μmol/L)。同时计算模拟了该五肽与ACE结合的机制,研究发现ACKEP的C末端的脯氨酸残基与赖诺普利和依那普利C末端结构相同,并且脯氨酸残基中咪唑环与ACE活性中心氨基酸残基更具亲和特性[73],从而导致该活性肽与ACE结合及抑制其活性方面具有显著效果。Rui等[74]使用碱性蛋白酶+风味蛋白酶和碱性蛋白酶+木瓜蛋白酶组合顺次加入的方式对菜豆蛋白进行水解制备ACE抑制肽进行了研究。结果发现,使用碱性蛋白酶+木瓜蛋白酶水解得到的水解产物相比于碱性蛋白酶+风味蛋白酶水解得到的水解产物具有更高的ACE抑制活性。这主要是由于碱性蛋白酶与木瓜蛋白酶酶切位点互补,获得更多ACE抑制肽。而当加入风味蛋白酶后,虽然增加了蛋白水解度,但同时却降低了水解物的ACE抑制活性,其原因可能是由于风味蛋白酶继续降解了具有活性的肽段使其失活。首先,在使用复合酶水解蛋白制备ACE抑制肽时,单一考察蛋白水解度不能全面反映ACE抑制肽活性的增强或减弱。其次使用复合酶水解时,选择恰当的蛋白酶对产生高ACE抑制活性多肽也是至关重要。风味蛋白酶作为一种外肽酶,容易切断多肽末端疏水氨基酸残基,而根据构效关系分析,末端疏水性氨基酸残基是决定该多肽是否具有ACE抑制活性的关键因素[14]。因此,风味蛋白的后续加入致使具有ACE抑制活性的多肽结构受到破坏,从而降低整体抑制活性。Ambigaipalan等[75]采用复合酶顺次加入的方法对椰枣子蛋白提取物进行水解制备ACE抑制肽,获得的水解物的ACE抑制活性大小依次为碱性蛋白酶+嗜热菌蛋白酶<碱性蛋白酶+风味蛋白酶<风味蛋白酶+嗜热菌蛋白酶<碱性蛋白酶+风味蛋白酶+嗜热菌蛋白酶。由此可知,虽然复合酶水解可以获得单酶水解所无法获得的新型ACE抑制肽,但是由于多种酶具有各自的酶切位点,所以在酶切过程中存在将已产生具有ACE抑制活性的肽继续水解而使其失活的现象。Pedroche等[76]在使用碱性蛋白酶+风味蛋白酶顺次水解鹰嘴豆蛋白制备ACE抑制肽时,同样发现使用风味蛋白酶使得水解物的ACE抑制活性下降的现象。因此,在使用复合酶进行水解时,应考虑各种蛋白酶酶切位点的交叉性,确保已产生具有ACE抑制活性结构的多肽不被进一步破坏从而降低其生物活性。随着对ACE抑制肽广泛的研究以及各种蛋白一级序列数据库的完善,利用计算机模拟复合酶水解蛋白产生ACE抑制肽对实际实验具有较好的指导作用。目前,模拟酶切蛋白分析活性肽的数据库主要有ProtParam、Blast、ExPASyPeptideCutter和BIOPEP。已有报道利用模拟酶切分析各种食源性蛋白获得各类活性肽如ACE抑制肽、抗凝血肽、抗氧化肽和二肽基肽酶抑制肽的研究[77-81]。Lafarga等[82]利用BIOPEP数据库选定了5种酶即菠萝蛋白酶、嗜热菌蛋白酶、胃蛋白酶、无花果蛋白酶和木瓜蛋白酶,对猪肉蛋白包括血红蛋白、胶原蛋白和血清白蛋白进行模拟酶切预测分析。分析结果表明猪肉蛋白是生产生物活性肽良好的来源,能够产生较多在治疗高血压方面起到重要作用的ACE、肾素和二肽基肽酶抑制肽。因此,在使用复合酶水解蛋白制备ACE抑制肽方面,如果进行先期计算模拟水解,能在提高抑制肽抑制活性和抑制肽产量方面均有良好的先期指导作用,避免了在ACE抑制肽筛选纯化工作量大的缺点,将酶解位点、蛋白一级序列和最终获得具有高ACE抑制活性肽结构之间建立直接联系,消除酶解过程中的盲目性和不确定性。表2列举近年利用复合酶水解不同蛋白源制备ACE抑制肽的信息。

表2 复合酶水解不同蛋白源制备的ACE抑制肽Table2 Preparation of ACE peptides derived from different proteins using a combination of different enzymes

目前,使用复合酶水解蛋白制备ACE抑制肽还处于简单的酶组合阶段,并没有考虑对复合酶的酶切位点进行先期理论设计,以避免对活性肽段的重复切割问题。因此,在使用复合酶水解制备ACE抑制肽时,在确保分离纯化得到较高ACE抑制肽的同时,应充分利用已建立起来的模拟酶切数据库,保证获得更多有活性的ACE抑制活性肽段。利用计算机计算模拟酶切过程将成为未来复合酶酶解蛋白制备生物活性肽的关注热点。

5 ACE抑制肽体内活性的评价

目前测定蛋白水解物或肽的降压活性通常采用体外ACE抑制活性进行评价,但体外ACE抑制活性的评价结果还需通过体内抑制活性进行进一步验证[92]。ACE抑制肽体内活性主要使用SHRs进行评价,主要考察其SBP和舒张压的变化情况。Kontani等[93]从大米蛋白水解物中分离纯化得到的ACE抑制肽IHRF有效地降低了SHRs的SBP。当以5 mg/kg(以体质量计,下同)剂量灌胃7 h后SBP下降了18 mmHg,以15 mg/kg剂量灌胃后SBP下降了39 mmHg。研究表明该抑制肽在体内也展现了抑制活性。García-Tejedor等[94]验证了不同给药量(3、7、10 mg/kg)的乳铁蛋白源的两种多肽(DPYKLRP和LRP)在体内抑制活性,研究发现这两种抑制肽在体内展现的抑制活性与给药量呈正相关性。此外,通过构建小肠上皮细胞模型,考察ACE抑制肽穿过小肠黏膜的吸收、转运和代谢的情况,可以间接对ACE抑制肽能否在体内发挥活性进行评价[95]。Caco-2源于人结肠癌细胞,能够形成与人小肠上皮细胞相类似的微绒毛结构,同时表达出与小肠上皮细胞相同的特征酶类[96]。VPP和IPP是由瑞士乳杆菌发酵乳中分离出具有ACE抑制活性的肽,祝倩等[97]通过Caco-2细胞模拟小肠吸收细胞分析了其对VPP和IPP的吸收转运机制,研究发现VPP和IPP属于旁路运输的小肠转运途径,具有较高的生物利用度,能够在体能发挥降压活性。Ding Long等[98]也建立了Caco-2细胞模型,评价了蛋清中获得的ACE抑制肽TNGIIR的转运机制,研究发现该抑制肽能够以完整的状态穿过Caco-2细胞单分子层,其运输方式也属于旁路运输,表明该抑制肽具有抗消化作用的能力并且能够直接在体内发挥降压作用。因此,除了体外测定多肽的ACE抑制活性外,体内生物活性的评价及其抗消化特性和转运机制也是鉴定多肽是否具有ACE抑制活性的重要指标。

6 结 语

尽管利用可食用蛋白源制备具有降压功能的ACE抑制肽已经引起关注,但其结构特性及其抑制肽构效关系还需进一步深入研究,为发现新型ACE抑制肽提供基础。在选择复合酶进行水解时,利用计算机进行模拟水解,考察酶切位点的互补性与交叉性,最大限度获得高活性、大量的ACE抑制肽是该研究领域的新热点。同时,为保障最终实现高效产业化生产,在利用蛋白酶催化水解蛋白制备ACE抑制肽过程中的可控定点水解,特异性高效制备ACE抑制活性肽等方面也将成为该研究领域的新方向。

[1] LIN L, LV S, LI B. Angiotensin-Ⅰ-converting enzyme (ACE)-inhibitory and antihypertensive properties of squid skin gelatin hydrolysates[J]. Food Chemistry, 2012, 131(1): 225-230. DOI:10.1016/ j.foodchem.2011.08.064.

[2] ONDETTI M, RUBIN B, CUSHMAN D. Design of specif i c inhibitors of angiotensin converting enzyme: new class of orally active antihypertensive agents[J]. Science, 1977, 196: 441-444. DOI:10.1126/ science.191908.

[3] BOUGATEF A, NEDJAR-ARROUME N, RAVALLEC-PL R, et al. Angiotensin Ⅰ-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitory activities of sardinelle (Sardinellaaurita) by-products protein hydrolysates obtained by treatment with microbial and visceral fish serine proteases[J]. Food Chemistry, 2008, 111(2): 350-356. DOI:10.1016/ j.foodchem.2008.03.074.

[4] ERDMANN K, CHEUNG B W, SCHRÖDER H. The possible roles of food-derived bioactive peptides in reducing the risk of cardiovascular disease[J]. The Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry, 2008, 19(10): 643-654. DOI:10.1016/j.jnutbio.2007.11.010.

[5] YU Y, HU J, MIYAGUCHI Y, et al. Isolation and characterization of angiotensin I-converting enzyme inhibitory peptides derived from porcine hemoglobin[J]. Peptides, 2006, 27(11): 2950-2956. DOI:10.1016/j.peptides.2006.05.025.

[6] FERREIRA S H, BARTELT D C, GREENE L J. Isolation of bradykinin-potentiating peptides from Bothrops jararac avenom[J]. Biochemistry, 1970, 9(13): 2583-2593. DOI:10.1021/bi00815a005.

[7] PHELAN M, AHERNE A, FITZGERALD R J, et al. Casein-derived bioactive peptides: biological effects, industrial uses, safety aspects and regulatory status[J]. International Dairy Journal, 2009, 19(11):643-654. DOI:10.1016/j.idairyj.2009.06.001.

[8] TERASHIMA M, BABA T, IKEMOTO N, et al. Novel angiotensinconverting enzyme (ACE) inhibitory peptides derived from boneless chicken leg meat[J]. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 2010, 58(12): 7432-7436. DOI:10.1021/jf100977z.

[9] BOSCHIN G, SCIGLIUOLO G M, RESTA D, et al. ACE-inhibitory activity of enzymatic protein hydrolysates from lupin and other legumes[J]. Food Chemistry, 2014, 145(7): 34-40. DOI:10.1016/ j.foodchem.2013.07.076.

[10] SUETSUNA K, MAEKAWA K, CHEN J R. Antihypertensive effects of Undaria pinnatifida (wakame) peptide on blood pressure in spontaneously hypertensive rats[J]. The Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry, 2004, 15(5): 267-272. DOI:10.1016/ j.jnutbio.2003.11.004.

[11] KUBA M, TANA C, TAWATA S, et al. Production of angiotensin I-converting enzyme inhibitory peptides from soybean protein with Monascus purpureus acid proteinase[J]. Process Biochemistry, 2005, 40(6): 2191-2196. DOI:10.1016/j.procbio.2004.08.010.

[12] KO S C, KANG N, KIM E A, et al. A novel angiotensin I-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitory peptide from a marine Chlorella ellipsoidea and its antihypertensive effect in spontaneously hypertensive rats[J]. Process Biochemistry, 2012, 47(12): 2005-2011. DOI:10.1016/ j.procbio.2012.07.015.

[13] MAO X Y, NI J R, SUN W L, et al. Value-added utilization of yak milk casein for the production of angiotensin-Ⅰ-converting enzyme inhibitory peptides[J]. Food Chemistry, 2007, 103(4): 1282-1287. DOI:10.1016/j.foodchem.2006.10.041.

[14] JIANG J, CHEN S, REN F, et al. Yak milk casein as a functional ingredient: preparation and identif i cation of angiotensin-Ⅰ-converting enzyme inhibitory peptides[J]. Journal of Dairy Research, 2007, 74(1):18-25. DOI:10.1017/S0022029906002056.

[15] FABRIS B, CHEN B, PUPIC V, et al. Inhibition of angiotensinconverting enzyme (ACE) in plasma and tissue[J]. Journal of Cardiovascular Pharmacology, 1990, 15(Suppl 2): 6-13. DOI:10.1097/00005344-199000152-00003.

[16] MENARD J, PATCHETT A A. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors[J]. Advnces in Protein Chemistry, 2001, 56(17): 13-75. DOI:10.1016/S0065-3233(01)56002-7.

[17] SPYROULIAS G A, GALANIS A S, PAIRAS G, et al. Structural features of angiotensin-Ⅰ converting enzyme catalytic sites:conformational studies in solution, homology models and comparison with other zinc metallopeptidases[J]. Current Topics in Medicinal Chemistry, 2004, 4(4): 403-429. DOI:10.2174/1568026043451294.

[18] HUBERT C, HOUOT A M, CORVOL P, et al. Structure of the angiotensin Ⅰ-converting enzyme gene. Two alternate promoters correspond to evolutionary steps of a duplicated gene[J]. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 1991, 266(23): 15377-15383.

[19] CONSORTIUM U. Activities at the universal protein resource (UniProt)[J]. Nucleic Acids Research, 2014, 42(11): 7486. DOI:10.1093/nar/gku469.

[20] SOUBRIER F, ALHENC-GELAS F, HUBERT C, et al. Two putative active centers in human angiotensin I-converting enzyme revealed by molecular cloning[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 1988, 85(24): 9386-9390. DOI:10.1073/pnas.85.24.9386.

[21] JUNOT C, GONZALES M F, EZAN E, et al. RXP 407, a selective inhibitor of the N-domain of angiotensin I-converting enzyme, blocks in vivo the degradation of hemoregulatory peptide acetyl-Ser-Asp-Lys-Pro with no effect on angiotensin I hydrolysis[J]. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics, 2001, 297(2): 606-611.

[22] RIORDAN J F. Angiotensin-I-converting enzyme and its relatives[J]. Genome Biology, 2003, 4(8): 225. DOI:10.1186/gb-2003-4-8-225.

[23] TURNER A J, HOOPER N M. The angiotensin-converting enzyme gene family: genomics and pharmacology[J]. Trends in Pharmacological Sciences, 2002, 23(4): 177-183. DOI:10.1016/S0165-6147(00)01994-5.

[24] LEE S H, QIAN Z J, KIM S K. A novel angiotensin Ⅰ converting enzyme inhibitory peptide from tuna frame protein hydrolysate and its antihypertensive effect in spontaneously hypertensive rats[J]. Food Chemistry, 2010, 118(1): 96-102. DOI:10.1016/ j.foodchem.2009.04.086.

[25] QUIST E E, PHILLIPS R D, SAALIA F K. Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitory activity of proteolytic digests of peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.) flour[J]. LWT-Food Science and Technology, 2009, 42(3): 694-699. DOI:10.1016/j.lwt.2008.10.008.

[26] JOHNSTON C I. Renin-angiotensin system: a dual tissue and hormonal system for cardiovascular control[J]. Journal of Hypertension, 1992, 10(7): 13-26. DOI:10.1097/00004872-199212007-00002.

[27] ASOODEH A, YAZDI M M, CHAMANI J. Purification and characterisation of angiotensin Ⅰ converting enzyme inhibitory peptides from lysozyme hydrolysates[J]. Food Chemistry, 2012, 131(1): 291-295. DOI:10.1016/j.foodchem.2011.08.039.

[28] PIHLANTO-LEPPALA A. Bioactive peptides derived from bovine whey proteins: opioid and ace-inhibitory peptides[J]. Trends in Food Science andTechnology, 2000, 11(9): 347-356. DOI:10.1016/S0924-2244(01)00003-6.

[29] POKORA M, ZAMBROWICZ A, DĄBROWSKA A, et al. An attractive way of egg white protein by-product use for producing of novel anti-hypertensive peptides[J]. Food Chemistry, 2014, 151(4):500-505. DOI:10.1016/j.foodchem.2013.11.111.

[30] BALTI R, NEDJAR-ARROUME N, BOUGATEF A, et al. Three novel angiotensin I-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitory peptides from cuttlefish (Sepia officinalis) using digestive proteases[J]. Food Research International, 2010, 43(4): 1136-1143. DOI:10.1016/ j.foodres.2010.02.013.

[31] SAIGA A, OKUMURA T, MAKIHARA T, et al. Action mechanism of an angiotensin Ⅰ-converting enzyme inhibitory peptide derived from chicken breast muscle[J]. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 2006, 54(3): 942-945. DOI:10.1021/jf0508201

[32] SHEIH I C, FANG T J, WU T K. Isolation and characterisation of a novel angiotensin I-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitory peptide from the algae protein waste[J]. Food Chemistry, 2009, 115(1): 279-284. DOI:10.1016/j.foodchem.2008.12.019.

[33] ANTHONY C S, CORRADI H R, SCHWAGER S L, et al. The Ndomain of human angiotensin-I-converting enzyme the role of N-glycosylation and the crystal structure in complex with an N domain-specific phosphinic inhibitor, RXP407[J]. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 2010, 285(46): 35685-35693. DOI:10.1074/jbc. M110.167866.

[34] CORRADI H R, SCHWAGER S L, NCHINDA A T, et al. Crystal structure of the N domain of human somatic angiotensin I-converting enzyme provides a structural basis for domain-specific inhibitor design[J]. Journal of Molecular Biology, 2006, 357(3): 964-974. DOI:10.1016/j.jmb.2006.01.048.

[35] GEORGIADIS D, BEAU F, CZARNY B, et al. Roles of the two active sites of somatic angiotensin-converting enzyme in the cleavage of angiotensin I and bradykinin insights from selective inhibitors[J]. Circulation Research, 2003, 93(2): 148-154. DOI:10.1161/01. RES.0000081593.33848.FC.

[36] WU J, ALUKO R E, NAKAI S. Structural requirements of sngiotensinⅠ-converting enzyme inhibitory peptides: quantitative structureactivity relationship modeling of peptides containing 4-10 amino acid residues[J]. QSAR & Combinatorial Science, 2006, 25(10): 873-880. DOI:10.1002/qsar.200630005.

[37] HOROVITZ Z P. Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors:mechanisms of action and clinical implications[M]. German: Baltimore and Munich, 1981: 156.

[38] CHEUNG H S, WANG F L, ONDETTI M A, et al. Binding of peptide substrates and inhibitors of angiotensin-converting enzyme. Importance of the COOH-terminal dipeptide sequence[J]. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 1980, 255(2): 401-407.

[39] KOHMURA M, NIO N, KUBO K, et al. Inhibition of angiotensinconverting enzyme by synthetic peptides of human β-casein[J]. Agricultural and Biological Chemistry, 1989, 53(8): 2107-2114. DOI:10.1080/00021369.1989.10869621.

[40] JANG A, JO C, KANG K S, et al. Antimicrobial and human cancer cell cytotoxic effect of synthetic angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitory peptides[J]. Food Chemistry, 2008, 107(1): 327-336. DOI:10.1016/j.foodchem.2007.08.036.

[41] CUSHMAN D, PLUŠČEC J, WILLIAMS N, et al. Inhibition of angiotensin-converting enzyme by analogs of peptides from Bothrops jararaca venom[J]. Experientia, 1973, 29(8): 1032-1035. DOI:10.1007/BF01930447.

[42] WU J P, ALUKO R E, NAKAI S. Structural requirements of angiotensinⅠ-converting enzyme inhibitory peptides: quantitative structure-activity relationship study of di-and tripeptides[J]. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 2006, 54(3): 732-738. DOI:10.1021/jf051263l.

[43] JUNG W K, MENDIS E, JE J Y, et al. Angiotensin Ⅰ-converting enzyme inhibitory peptide from yellowf i n sole (Limanda aspera) frame protein and its antihypertensive effect in spontaneously hypertensive rats[J]. Food Chemistry, 2006, 94(1): 26-32. DOI:10.1016/ j.foodchem.2004.09.048.

[44] GUERRERO L, CASTILLO J, QUIÑONES M, et al. Inhibition of angiotensin-converting enzyme activity by flavonoids: structureactivity relationship studies[J]. PLoS ONE, 2012, 7(11): e49493. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0049493.

[45] ZHANG Y, SUN W, ZHAO M, et al. Improvement of the ACE-inhibitory and DPPH radical scavenging activities of soya protein hydrolysates through pepsin pretreatment[J]. International Journal of Food Science & Technology, 2015, 50(10): 2175-2182. DOI:10.1111/ ijfs.12856.

[46] ALUKO R E. Antihypertensive peptides from food proteins[J]. Annual Review of Food Science and Technology, 2015, 6(1): 235-262. DOI:10.1146/annurev-food-022814-015520.

[47] KETNAWA S, RAWDKUEN S. Enzymatic method for ACE inhibitory peptide derived from aquatic resources: areview[J]. International Journal of Biology, Pharmacy and Allied Sciences, 2013, 2: 469-494.

[48] GOBBETTI M, FERRANTI P, SMACCHI E, et al. Production of angiotensin-Ⅰ-converting-enzyme-inhibitory peptides in fermented milks started by lactobacillus delbrueckiisubsp. bulgaricus SS1 and Lactococcus lactis subsp. cremoris FT4[J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2000, 66(9): 3898-3904. DOI:10.1128/AEM.66.9.3898-3904.2000.

[49] LEE J K, HONG S, JEON J K, et al. Purif i cation and characterization of angiotensin I converting enzyme inhibitory peptides from the rotifer, Brachionus rotundiformis[J]. Bioresource Technology, 2009, 100(21):5255-5259. DOI:10.1016/j.biortech.2009.05.057.

[50] LI G H, WAN J Z, LE G W, et al. Novel angiotensin Ⅰ-converting enzyme inhibitory peptides isolated from alcalasehydrolysate of mung bean protein[J]. Journal of Peptide Science, 2006, 12(8): 509-514. DOI:10.1002/psc.758.

[51] WIJESEKARA I, QIAN Z J, RYU B, et al. Purif i cation and identif i cation of antihypertensive peptides from seaweed pipef i sh (Syngnathus schlegeli) muscle protein hydrolysate[J]. Food Research International, 2011, 44(3):703-707. DOI:10.1016/j.foodres.2010.12.022.

[52] GOMEZ-GUILLEN M C, GIMENZ B, LOPEZ-CABALLERO M E, et al. Functional and bioactive properties of collagen and gelatin from alternative sources: a review[J]. Food Hydrocolloids, 2011, 25(8):1813-1827. DOI:10.1016/j.foodhyd.2011.02.007.

[53] BYUN H G, KIM S K. Purif i cation and characterization of angiotensinⅠ converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitory peptides from Alaska pollack (Theragra chalcogramma) skin[J]. Process Biochemistry, 2001, 36(12): 1155-1162. DOI:10.1016/S0032-9592(00)00297-1.

[54] SAITO Y, WANEZAKI K, KAWATO A, et al. Structure and activity of angiotensin Ⅰ converting enzyme inhibitory peptides from sake and sake lees[J]. Bioscience, Biotechnology, and Biochemistry, 1994, 58(10): 1767-1771. DOI:10.1271/bbb.58.1767.

[55] MARRUFO-ESTRADA D M, SEGURA-CAMPOS M R, CHELGUERRERO L A, et al. Defatted Jatrophacurcas flour and protein isolate as materials for protein hydrolysates with biological activity[J]. Food Chemistry, 2013, 138(1): 77-83. DOI:10.1016/ j.foodchem.2012.09.033.

[56] di BERNARDINI R, MULLEN A M, BOLTON D, et al. Assessment of the angiotensin-Ⅰ-converting enzyme (ACE-Ⅰ) inhibitory and antioxidant activities of hydrolysates of bovine brisket sarcoplasmic proteins produced by papain and characterisation of associated bioactive peptidic fractions[J]. Meat Science, 2012, 90(1): 226-235. DOI:10.1016/j.meatsci.2011.07.008.

[57] LI H, ALUKO R E. Identification and inhibitory properties of multifunctional peptides from pea protein hydrolysate[J]. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 2010, 58(21): 11471-11476. DOI:10.1021/jf102538g.

[58] WU S G, FENG X Z, LAN X D, et al. Purif i cation and identif i cation of angiotensin-I converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitory peptide from lizard fish (Saurida elongata) hydrolysate[J]. Journal of Functional Foods, 2015, 13: 295-299. DOI:10.1016/j.jff.2014.12.051.

[59] NIHON K S. Nikkei biotechnology annual report[R]. Japan: Nihon Keizai Shinbunsha, 1997.

[60] OTTE J, SHALABY S M, ZAKORA M, et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitory activity of milk protein hydrolysates: effect of substrate, enzyme and time of hydrolysis[J]. International Dairy Journal, 2007, 17(5): 488-503. DOI:10.1016/j.idairyj.2006.05.011.

[61] HE R, ALASHI A, MALOMO S A, et al. Antihypertensive and free radical scavenging properties of enzymatic rapeseed protein hydrolysates[J]. Food Chemistry, 2013, 141(1): 153-159. DOI:10.1016/ j.foodchem.2013.02.087.

[62] IKEDA A, ICHINO H, KIGUCHIYA S, et al. Evaluation and identification of potent angiotensin-Ⅰ converting enzyme inhibitory peptide derived from dwarf gulper shark (Centrophorus atromarginatus)[J]. Journal of Food Processing and Preservation, 2015, 39(2): 107-115. DOI:10.1111/jfpp.12210.

[63] ZHANG Y, OLSEN K, GROSSI A, et al. Effect of pretreatment on enzymatic hydrolysis of bovine collagen and formation of ACE-inhibitory peptides[J]. Food Chemistry, 2013, 141(3): 2343-2354. DOI:10.1016/j.foodchem.2013.05.058.

[64] HE R, MALOMO S A, ALASHI A, et al. Purif i cation and hypotensive activity of rapeseed protein-derived renin and angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitory peptides[J]. Journal of Functional Foods, 2013, 5(2): 781-789. DOI:10.1016/j.jff.2013.01.024.

[65] MUGURUMA M, AHHMED A M, KATAYAMA K, et al. Identification of pro-drug type ACE inhibitory peptide sourced from porcine myosin B: evaluation of its antihypertensive effects in vivo[J]. Food Chemistry, 2009, 114(2): 516-522. DOI:10.1016/ j.foodchem.2008.09.081.

[66] SAMARAKOON K W, KWON O N, KO J Y, et al. Purification and identification of novel angiotensin-I converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitory peptides from cultured marine microalgae (Nannochloropsis oculata) protein hydrolysate[J]. Journal of Applied Phycology, 2013, 25(5): 1595-1606. DOI:10.1007/s10811-013-9994-6.

[67] LIM C W, KIM Y K, YEUN S M, et al. Purification and characterization of angiotensin-1 converting enzyme (ACE)-inhibitory peptide from the jellyf i sh, Nemopilema nomurai[J]. African Journal of Biotechnology, 2016, 12(15): 1888-1893. DOI:10.5897/AJB11.2677.

[68] ZAREI M, FORGHANI B, EBRAHIMPOUR A, et al. In vitro and in vivo antihypertensive activity of palm kernel cake protein hydrolysates:sequencing and characterization of potent bioactive[J]. Industrial Crops and Products, 2015, 76: 112-120. DOI:10.1016/j.indcrop.2015.06.040.

[69] WU H, XU N, SUN X, et al. Hydrolysis and purification of ACE inhibitory peptides from the marine microalga Isochrysis galbana[J]. Journal of Applied Phycology, 2015, 27(1): 351-361. DOI:10.1007/ s10811-014-0347-x.

[70] MIRZAEI M, MIRDAMADI S, EHSANI M R, et al. Purification and identification of antioxidant and ACE-inhibitory peptide from Saccharomyces cerevisiae protein hydrolysate[J]. Journal of Functional Foods, 2015, 19: 259-268. DOI:10.1016/j.jff.2015.09.031.

[71] YAMADA A, SAKURAI T, OCHI D, et al. Novel angiotensin I-converting enzyme inhibitory peptide derived from bovine casein[J]. Food Chemistry, 2013, 141(4): 3781-3789. DOI:10.1016/ j.foodchem.2013.06.089.

[72] LI P, JIA J, FANG M, et al. In vitro and in vivo ACE inhibitory of pistachio hydrolysates and in silico mechanism of identif i ed peptide binding with ACE[J]. Process Biochemistry, 2014, 49(5): 898-904. DOI:10.1016/j.procbio.2014.02.007.

[73] TERASHIMA M, OE M, OGURA K, et al. Inhibition strength of short peptides derived from an ACE inhibitory peptide[J]. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 2011, 59(20): 11234-11237. DOI:10.1021/jf202902r.

[74] RUI X, BOYE J I, SIMPSON B K, et al. Angiotensin Ⅰ-converting enzyme inhibitory properties of Phaseolus vulgaris bean hydrolysates:effects of different thermal and enzymatic digestion treatments[J]. Food Research International, 2012, 49(2): 739-746. DOI:10.1016/ j.foodres.2012.09.025.

[75] AMBIGAIPALAN P, Al-KHALIFA A S, SHAHIDI F. Antioxidant and angiotensin Ⅰ converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitory activities of date seed protein hydrolysates prepared using Alcalase, Flavourzyme and Thermolysin[J]. Journal of Functional Foods, 2015, 18: 1125-1137. DOI:10.1016/j.jff.2015.01.021.

[76] PEDROCHE J, YUST M M, GIRÓN-CALLE J, et al. Utilisation of chickpea protein isolates for production of peptides with angiotensin I-converting enzyme (ACE)-inhibitory activity[J]. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture, 2002, 82(9): 960-965. DOI:10.1002/ jsfa.1126.

[77] CHANG Y W, ALLI I. In silico assessment: Suggested homology of chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) legumin and prediction of ACE-inhibitory peptides from chickpea proteins using BLAST and BIOPEP analyses[J]. Food Research International, 2012, 49(1): 477-486. DOI:10.1016/j.foodres.2012.07.006

[78] GU Y, MAJUMDER K, WU J. QSAR-aided in silico approach in evaluation of food proteins as precursors of ACE inhibitory peptides[J]. Food Research International, 2011, 44(8): 2465-2474.

[79] IWANIAK A, DZIUBA J. Analysis of domains in selected plant and animal food proteins-precursors of biologically active peptides-in silicoapproach[J]. Food Science and Technology International, 2009, 15(2): 179-191. DOI:10.1177/1082013208106320.

[80] IWANIAK A, DZIUBA J. Animal and plant proteins as precursors of peptides with ACE inhibitory activity: an in silico strategy of protein evaluation[J]. Food Technology and Biotechnology, 2009, 47(4): 441-449.

[81] LACROIX I M, LI-CHAN E C. Evaluation of the potential of dietary proteins as precursors of dipeptidyl peptidase (DPP)-Ⅳ inhibitors by an in silico approach[J]. Journal of Functional Foods, 2012, 4(2): 403-422. DOI:10.1016/j.jff.2012.01.008.

[82] LAFARGA T, O’CONNOR P, HAYES M. Identification of novel dipeptidyl peptidase-Ⅳ and angiotensin-Ⅰ-converting enzyme inhibitory peptides from meat proteins using in silico analysis[J]. Peptides, 2014, 59(9): 53-62. DOI:10.1016/j.peptides.2014.07.005.

[83] WANG C, TIAN J, WANG Q. ACE inhibitory and antihypertensive properties of apricot almond meal hydrolysate[J]. European Food Research and Technology, 2011, 232(3): 549-556. DOI:10.1007/ s00217-010-1411-7.

[84] MEMARPOOR-YAZDI M, ASOODEH A, CHAMANI J. Structure and ACE-inhibitory activity of peptides derived from hen egg white lysozyme[J]. International Journal of Peptide Research and Therapeutics, 2012, 18(4): 353-360. DOI:10.1007/s10989-012-9311-2.

[85] RAO S, SUN J, LIU Y, et al. ACE inhibitory peptides and antioxidant peptides derived from in vitro digestion hydrolysate of hen egg white lysozyme[J]. Food Chemistry, 2012, 135(3): 1245-1252. DOI:10.1016/ j.foodchem.2012.05.059.

[86] GU Y, WU J. LC-MS/MS coupled with QSAR modeling in characterising of angiotensin I-converting enzyme inhibitory peptides from soybean proteins[J]. Food Chemistry, 2013, 141(3): 2682-2690. DOI:10.1016/j.foodchem.2013.04.064.

[87] BOSCHIN G, SCIGLIUOLO G M, RESTA D, et al. Optimization of the enzymatic hydrolysis of lupin (Lupinus) proteins for producing ACE-inhibitory peptides[J]. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 2014, 62(8): 1846-1851. DOI:10.1021/jf4039056.

[88] YANG Y, MARCZAK E D, YOKOO M, et al. Isolation and antihypertensive effect of angiotensin Ⅰ-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitory peptides from spinach Rubisco[J]. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 2003, 51(17): 4897-4902. DOI:10.1021/ jf4039056.

[89] WU Q, CAI Q F, TAO Z P, et al. Purif i cation and characterization of a novel angiotensin I-converting enzyme inhibitory peptide derived from abalone (Haliotis discus hannai Ino) gonads[J]. European Food Research and Technology, 2015, 240(1): 137-145. DOI:10.1007/ s00217-014-2315-8.

[90] GARCIA-MORENO P J, ESPEJO-CARPIO F J, GUADIX A, et al. Production and identification of angiotensin I-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitory peptides from Mediterranean fi sh discards[J]. Journal of Functional Foods, 2015, 18: 95-105. DOI:10.1016/j.jff.2015.06.062.

[91] AISSAOUI N, ABIDI F, MARZOUKI M N. ACE inhibitory and antioxidant activities of red scorpionf i sh (Scorpaena notata) protein hydrolysates[J]. Journal of Food Science and Technology, 2015, 52(11): 7092-7102. DOI:10.1007/s13197-015-1862-8.

[92] VERMEIRSSEN V, van CAMP J, VERSTRAETE W. Bioavailability of angiotensin Ⅰ converting enzyme inhibitory peptides[J]. British Journal of Nutrition, 2004, 92(3): 357-366. DOI:10.1079/ BJN20041189.

[93] KONTANI N, OMAE R, KAGEBAYASHI T, et al. Characterization of Ile-His-Arg-Phe, a novel rice-derived vasorelaxing peptide with hypotensive and anorexigenic activities[J]. Molecular Nutrition & Food Research, 2014, 58(2): 359-364. DOI:10.1002/mnfr.201300334.

[94] GARCIA-TEJEDOR A, SANCHEZ-RIVERA L, CASTELLO-RUIZ M, et al. Novel antihypertensive lactoferrin-derived peptides produced by Kluyveromyces marxianus: gastrointestinal stability profile and in vivo angiotensin I-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibition[J]. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 2014, 62(7): 1609-1616. DOI:10.1021/jf4053868.

[95] 祝倩, 郭宇星, 潘道东. 利用Caco-2细胞模型评价乳源ACE抑制肽小肠吸收机制的研究进展[J]. 食品科学, 2013, 34(9): 330-335. DOI:10.7506/spkx1002-6630-201309066.

[96] FOGH J, FOGH J M, ORFEO T. One hundred and twenty-seven cultured human tumor cell lines producing tumors in nude mice[J]. Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 1977, 59(1): 221-226. DOI:10.1093/jnci/59.1.221.

[97] 祝倩, 郭宇星, 潘道东, 等. Caco-2细胞模型构建及抗高血压肽VPP和IPP小肠吸收机制研究[J]. 食品科学, 2014, 35(15): 226-231. DOI:10.7506/spkx1002-6630-201415046.

[98] DING L, WANG L, YU Z, et al. Digestion and absorption of an egg white ACE-inhibitory peptide in human intestinal Caco-2 cell monolayers[J]. International Journal of Food Sciences and Nutrition, 2016, 67(2): 111-116. DOI:10.3109/09637486.2016.1144722.

Progress in Structure-Activity Relationship and Enzymatic Preparation of ACE Inhibitory Peptides

LIN Kai1, HAN Xue1, ZHANG Lanwei1,2,*, QIAO Fei1, CHENG Dayou1

(1. School of Chemistry and Chemical Engineering, Harbin Institute of Technology, Harbin 150090, China; 2. College of Food Science and Engineering, Ocean University of China, Qingdao 266003, China)

Hypertension is a considerable public health problem worldwide. Angiotensin-Ⅰ converting enzyme (dipeptidylcarboxypeptidase, EC 3.4.15.1, ACE) plays a critical role in regulating blood pressure through the renninangiotensin system (RAS) and kallikrein-kinnin system (KKS). Recently, numerous studies aimed at alleviating hypertension have focused on the generation and isolation of ACE-inhibitory peptides from various food sources. A number of studies have reported the structure-activity relationship of food protein-derived antihypertensive peptides, especially the effect of the primary structure on the potency. Compared with synthetic chemical drugs, ACE inhibitory peptides derived from food proteins are considered to be safer and milder. Nowadays, one of the most widely used techniques to liberate ACE inhibitory peptides is enzymatic hydrolysis. This technique involves one or more proteases at the optimum temperature and pH conditions. In this review, in order to provide a theoretical guidance for the preparation of high-quality ACE inhibitory peptides, we review recent reports on the structure-activity relationship and enzymatic preparation of ACE inhibitory peptides.

angiotensin-Ⅰ converting enzyme inhibitors; antihypertensive mechanism; structure-activity relationship; enzymatic preparation

10.7506/spkx1002-6630-201703042

TS201.2

A

1002-6630(2017)03-0261-10

林凯, 韩雪, 张兰威, 等. ACE抑制肽构效关系及其酶法制备的研究进展[J]. 食品科学, 2017, 38(3): 261-270. DOI:10.7506/spkx1002-6630-201703042. http://www.spkx.net.cn

LIN Kai, HAN Xue, ZHANG Lanwei, et al. Progress in structure-activity relationship and enzymatic preparation of ACE inhibitory peptides[J]. Food Science, 2017, 38(3): 261-270. (in Chinese with English abstract)

10.7506/spkx1002-6630-201703042. http://www.spkx.net.cn

2016-03-31

“十二五”农村领域国家科技计划项目(2013BAD18B05-05);国家乳品加工技术研发分中心开放课题(HL2015-1)作者简介:林凯(1989—),男,博士研究生,研究方向为乳品科学与发酵工程。E-mail:linkai@hit.edu.cn

*通信作者:张兰威(1961—),男,教授,博士,研究方向为乳品科学。E-mail:zhanglw@hit.edu.cn