使用泥土!马丁·劳奇的生活与工作

奥托·卡普芬格

徐知兰 译

使用泥土!马丁·劳奇的生活与工作

奥托·卡普芬格

徐知兰 译

节选自马丁·劳奇的《优雅的泥土——夯土建筑与设计》, 奥托·卡普芬格和马尔科·索尔(编著),细部出版社,慕尼黑,2015年,第6-13页(图1,2)由细部出版社再版。

这本书讲述了一位另类思考者的成功故事——他在字面意义上“脚踏实地”的工作方法使他通过真实的个人经验获得了一种生态社会学的立场。最初,他把自己定义为对当地“感兴趣”的外来者,后来逐渐成为享誉全球的权威,人们对他具有先进生态学理念建筑的思想产生了迫切需要。在这本书里,马丁·劳奇展示了他在这30年来在地区层面——及越来越多在国际层面所取得的成就。不折不扣地说,他的基础研究以自下而上的方式开展。通过不断地在不同尺度的项目中运用经过测试的先进技术,他的这种工作方法形成了一整套知识体系,现在能为更多的读者所了解,还包括详细的建筑平面图和说明。这本书不仅仅是劳奇用来展示他和许多著名设计师共同合作完成作品的平台——其合作者包括罗杰·博尔茨豪瑟建筑师事务所、奥拉维尔·埃利亚松1)、赫尔佐格与德梅隆事务所、哈尔曼·考夫曼建筑师事务所、马尔特·马尔特建筑师事务所、米勒和马兰塔建筑师事务所、斯诺赫塔建筑事务所、马特奥·图恩和昆特·弗伊格特等;《优雅的泥土》一书也恰好是以泥土作为材料进行当代城市规划与建筑的教育大纲,颇具全球意义。

劳奇对生土建筑技术的了解并不是通过建筑设计,而是通过他在1970年代后期作为陶瓷艺术家、窑炉建造师和雕塑家的训练和作品获得的。他对工艺美术的喜爱和在设计环境时的艺术自觉,及其极端节约资源的生活方式,都形成于在奥地利偏僻而朴实无华的福拉尔贝格地区的成长经历。他也同样受到来自国外的极大影响——和他的一些兄长一样,1980年他曾在非洲开发组织参加了为期几个月的志愿者项目。他在那里邂逅了“原始”的文化和建造技术,这些技术明显有效地形成了紧凑的生命周期,并能由此最大程度地利用资源,并同时产生了一种意识,即对进口工业经济的、野蛮的替代性技术的意识,认识到它们都对气候和生态环境产生了更恶劣的影响、都不可再生、且难以修复。

在非洲,劳奇的艺术直觉获得了全球化的视野——他产生了用这些“贫穷的”、具有艺术气息的原始材料进行创作的主观冲动,由此找到了他的创作对象及其客观而复杂的文化背景。劳奇对使用粘土作为手工艺创作原料的兴趣逐渐发展为用泥土进行建筑设计,并直面由此带来的所有挑战和要求。浇铸和烧制瓦片的工作变成大尺度的造型与建造过程——把泥土塑造成可以使用的可居住空间。1983年,他向当时维也纳应用技术大学陶瓷系系主任马特奥·图恩提交了自己的论文题目。这篇论文以《壤土、粘土、泥土》为题,描述了夯土技术作为产生自本土的文化技术形式所经历的现代化过程——无论其本土是在非洲还是在欧洲。

自此以后,劳奇开始追求一种具有普遍意义的理想,可以用几句话来表达:

以一种能让一座房屋在百年之后回归“自然”的方式进行建造——不留下任何残迹或污染——并分解为原来的材料成分;

以和自然生命周期相协调的方式进行建造,并在建筑施工、运营和拆除过程中尽可能不使用石油能源;

以可以在当地获取的低成本材料进行建造——使用采自施工现场的泥土,它们应该尽可能成分单一且未经加工;

发展夯土建筑的思想,使它在技术和物流方面能够跟上时代,让全世界的大多数人都能由此利用这项技术显著改善他们的生活水准。

1.2 《优雅的泥土——夯土建筑与设计》装帧与内页,细部出版社,慕尼黑/Book binding and inside pages of Refined Earth - Construction and design with Rammed Earth, Edition detail, Munich(摄影/Photos: Fotostudio Roth)

他一直以来都对不用任何其他材料饰面或进行表面处理的夯土技术特别感兴趣。表面不抹灰的粘土砌筑过程,如那些劳奇在法国和德国见到的、默默无名却保存良好的19世纪建筑,具有突出的自我表现力——和低温烧制的未上釉陶器一样。层叠的墙面结构形成了其自身特有的装饰性外观。纯粹的结构、色彩和材料质感都在填压和夯实的过程中得到了保留和强调。劳奇凭借其作为陶瓷艺术家对材料成分、物理化学条件及其影响效果所特有的敏感度,依靠技术进步与形式复杂性的协同作用,开始重新讲述夯土砌筑的语汇,使之适应当代标准,并再次展现出生土建筑材料的全部感官潜力。

由此,他设法避免了譬如为了弥补传统粘土砌筑技术的某些缺陷而需要在其中添加水泥的做法,这会损害夯土建筑的某些基本品质,如再循环的便捷程度、透气性或具有最小熵值的性质。作为替代方案,他尽可能地改善这种天然材料的混合成分,优化夯实的技术过程和模板形式,并引入加固层,对传统技术进行系统性的发展,而不舍弃其基本的结构原则。他从零开始探索施工使用的工具、流程和模板类型,然后对它们进行评估和改进;还建造了许多试验墙,在此过程中获得的实际经验则被立刻运用到接下来的一系列试验中。

劳奇于1982年首次在建筑中尝试他的试验技术,他和本土建筑师如罗伯特·费尔伯和鲁道夫·瓦格合作完成了一系列为对技术试验持开放态度的家庭成员和朋友们建造的小型建筑项目。他为哥哥约翰内斯在施林斯建造的住宅是福拉尔贝格地区第一座真正的现代木结构和夯土材料建筑。约翰内斯是一位农场主和锁匠,毕业于维也纳美术学院,曾在赞比亚、乌干达和坦桑尼亚参加了许多开发项目。建在柏林米特区的忏悔教堂则是其建筑实践的明确转折点(图3,4)。这处供人沉思的公共空间于1999-2000年根据柏林建筑师彼得·扎森罗特和鲁道夫·赖特曼绘制的平面图纸逐渐建设完成,它建在一座过去为砌起柏林墙而被炸毁的教堂基础上,这里曾被称为“死亡地带”。这座椭圆形的忏悔教堂高7m,一层平面和祭坛空间用夯土砌筑完成,并以木结构屋顶覆盖。这是德国几百年来第一座使用夯土技术建成的建筑,因此需要经过特别的许可程序。由于当时并没有针对夯土墙荷载的标准或建筑规范,许可部门和工程师们发现他们处于未曾探索的领域——对这座建筑提出的许多要求之一竟然还包括需要采用是正常值7倍的静力安全系数!此外,项目还需要进行外部监理和科技监督——这项工作由柏林科技大学完成。经过若干年,经历了无数次的试验过程、制作了无数试验样品和撰写了许多冗余的专家报告之后,这项古老而全球通用的建造技术终于能够融入我们的技术时代并获得首肯。

涉及到生态学标准的时候,马丁·劳奇也许提出了许多根本性的要求,但他在其作品中所展现的建筑与艺术天份却丝毫不会令人联想起原教旨主义的思想。在完成了备受瞩目的柏林忏悔教堂和为瑞士巴塞尔动物园建造的大型建筑之后,他与罗杰·博尔茨豪瑟合作,在施林斯为自己设计了一座三层高的住宅和工作室,代表了他对自己在当时已经积累的所有经验的重新整合 (图5,本刊P52)。正是在这里,现代夯土建筑终于能脱离幼稚的生态学的陈词滥调,而转向技术的成熟与形式的明晰,这在几年前甚至无法想象。劳奇控制了几乎所有的建筑元素——从基础延伸到墙面、地面、楼板、楼梯和门窗开洞——甚至对瓦的各种运用方式、水池、壁炉的形式、以及墙面和地面的表面处理方式也同样如此。这座3层楼建筑的每一个细节——作为与罗杰·博尔茨豪瑟意气相投的合作成果——毫无疑问地实现了他的部分理想,突出了夯土材料全面的物理和审美品质——从泥土的粗颗粒感到陶瓷般的精美质感应有尽有。

这座建筑荣获了各种国内和国际奖项,在全世界得到宣传出版,并为劳奇获得更大尺度的项目打开了大门。我有幸能在2008年项目正要竣工时步入这座建筑,并为之感到震惊——令人赞叹的震惊!我在1996-1997年间开始对福拉尔贝格地区的建筑进行研究,从此就对马丁的作品非常熟悉。2001年,我们在一份3种语言的出版物《夯土》杂志上合作,为一家业内领先的专业出版社工作——这代表着对他的工作进行第一次大规模的梳理总结。但当我在他为自己和全家设计的这座住宅和工作室里第一次亲眼目睹这种建筑品质的巨大飞跃时,我只能目瞪口呆而倍感惊喜。从室外到地面层的一切看起来都很熟悉,是我能想象到的样子。但随着我爬上主楼层,却发生了令人感动的变化。从楼下颗粒粗糙的生土材料氛围中来到楼上之后,我进入了闪烁着象牙色光泽的房间,视线在色彩明快、朝气蓬勃的灰色上蜡夯土地面、浅奶白色的窗户表面、用亚麻籽油和石蜡上光的移门嵌板、以及拥有天鹅绒般触感的墙面(同时作为火炕式供暖设备)和天花板的泥土抹灰之间来回切换。顶层设有卧室、办公室和浴室,精致的处理方法在这里得到了进一步的表达,夯土的表面产生了雪花石膏般光洁的效果。这一效果很大程度上产生于运用在烧毛地面和墙面砖上的乐烧2)技术,使其拥有富于丝缎般光泽而深浅不一的装饰性色彩——这项技术是马丁的太太、陶瓷艺术家玛尔塔·劳奇-德贝维奇和他的儿子平面设计师塞巴斯蒂安·劳奇共同创造的。

劳奇把他的技术所具有精神气质的核心描述为:“环绕着我们的围合结构应该能和我们的身体一样进行呼吸和扩散。我的建筑因此刻意设计为没有包裹或封闭的状态,也不用人工制造或高密度、消耗大量能量的材料建成。而是让它们以原生的状态进行组合和修饰,就像寿司——刻意不烧煮加工。整座建筑的实质能够由此保持可渗透性,这意味着它能够有效地面对使用和维护的需求,并最小程度地对抗长期的降解与再循环的过程。”罗杰·博尔茨豪瑟补充道:“这种古老而直接的手工艺和清晰的建筑语言产生了与景观环境极为融合的建筑。在许多方面,它都意味着地平线得到了真正的拓展。这些原则应该成为未来建筑设计普遍策略的基础。”这个项目切实地表达了几乎不可思议的可能性——它不仅消除了建筑中劳动、知识和材料之间的边界——这种区隔状态占据了我们目前高科技专业时代的主导地位;它也可以用能够想象到的最小熵值的材料来满足我们对建造、居住和舒适生活的要求——并在此过程中产生了全球适用的范式。

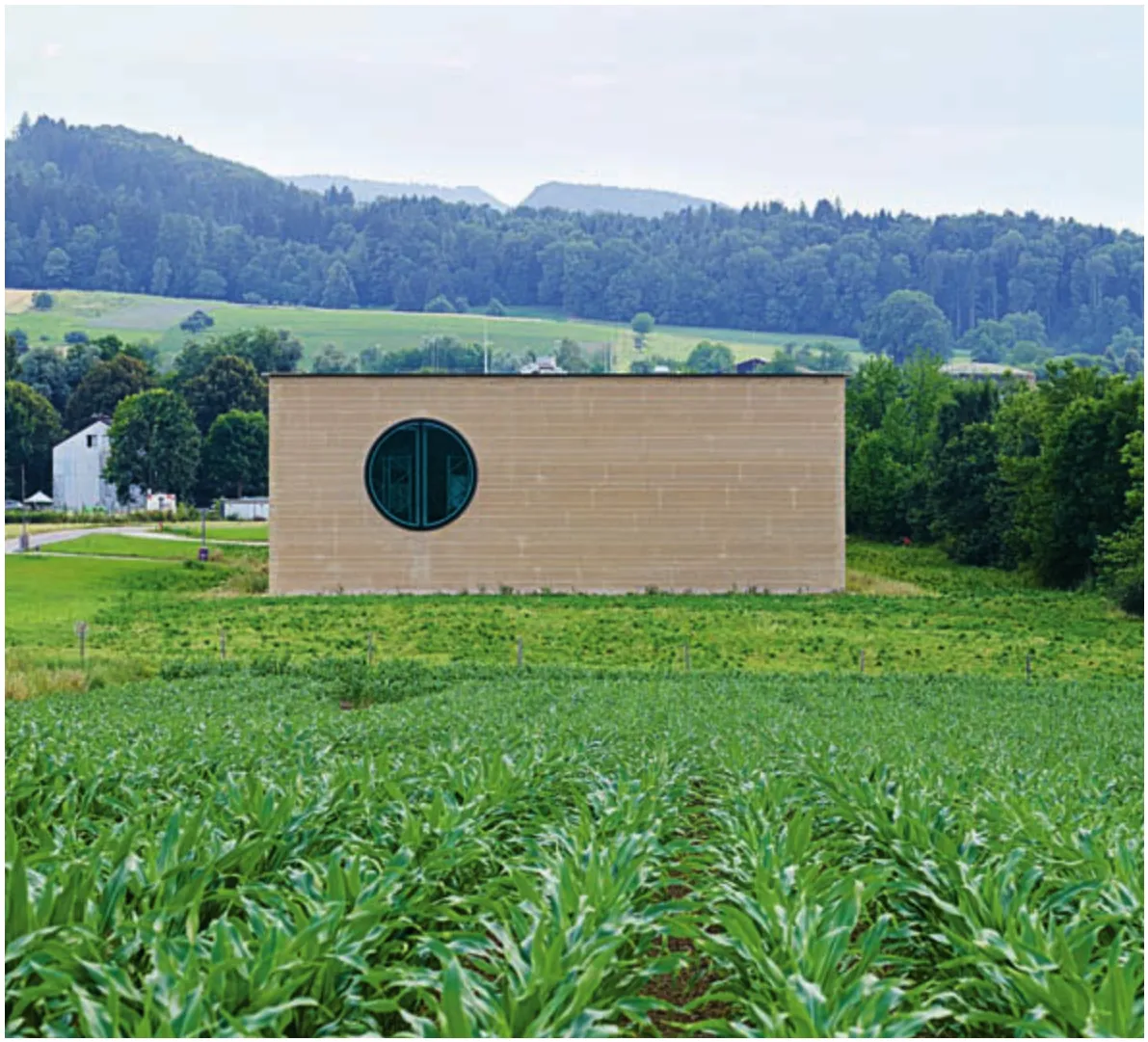

对于劳奇与赫尔佐格与德梅隆建筑师事务所、斯诺赫塔建筑事务所合作的更近期的国际项目,新一轮的创新不仅是必要的,也是至关重要的——它包括对手工夯土技术的改进,使它能够满足工业化规模生产、预制、物流的要求,以及满足综合性、大规模建设项目的成本核算要求。劳奇开发了自己的机器来应对这一挑战——他发明了一个能向模板内自动灌浆并进行机械搅拌的机器人。这个生产系统可以制作模板长度在50~80m之间的任何厚度的夯土块。拆模之后,经过搅拌压实的夯土块——与整块模板一样长——可以切割为任何尺度的构件。构件的尺寸则主要取决于如何运输,且尤其取决于起重机的荷载能力,通常最大可达5t。这一技术已经在最近位于瑞士劳芬的利口乐草药中心(图6,本刊P82)和瑞士鸟类学院的访客中心项目中证明了其价值(本刊P88)。

劳奇长期在欧洲、亚洲和非洲做各种讲座和组织工作室。也许,在他各种由小到大、尺度不一的建成作品中,影响最为广泛的并不是那些位于建筑作品丰富的福拉尔贝格地区的美丽住宅,或是与国际知名的建筑梦想家合作完成的令人瞩目的作品,而是他在南非为大学项目和样板项目所做的咨询工作——在约翰内斯堡或是孟加拉国。在那里,他通过教会当地人使用有效的技术,以自己的专业知识支持、并仍在支持那些真正需要以简单、廉价和适应气候的方式为自己建造房屋的人们,由此推广了一种可持续发展的建造方法,它可以替代过去输出的建造方式,且不需要依赖大型技术和需要兼容工业化要求的“外国援助”。劳奇在孟加拉国——一个人口极度增长、居住和生活水平非常糟糕的国家——与建筑师安娜·赫里格尔开展合作,他们共同推动的学校与住宅技术咨询和支持项目获得了2007年的阿卡汗建筑奖与2008年世界建筑社区奖。劳奇表示:“巨大的进步在于能向人们表明,他们可以用施工现场的泥土自己动手建造廉价的二层楼房屋——不需要任何附加的技术——并营造出气候品质最为舒适的空间。我们通过组织公共工作室和共同建造房屋作为范例的方法达成了这一目标。由于木材在当地非常珍贵,我们最后不得不使用混凝土板。但这只占在那里建造的新住宅楼的一小部分。我经常去南半球参加各种会议,那里的人普遍认为夯土建筑能通过加入水泥得到性能的改善,以便融入已经建立起来的工业生产体系。其中唯一的问题是,为了挣得一袋水泥,工人现在需要增加3倍于过去的工作时间,因为需求实在过于旺盛。而纯粹夯土建筑的政治意味在于,它可以应用在任何充分独立于政治游说、股票价格和工业价格控制的地方,只需要用简单的手工技术就能够建造生态环保的高品质房屋。在我们的世界,劳动力价格特别昂贵,手工建造的夯土建筑实际上是一件奢侈品。而在劳动力随处可得的国家,比如埃及,我在施林斯建的住宅可能会便宜大约60%,而且甚至可能成为一种标准的住宅样式!如果我们要继续在全世界范围内用和工业化国家同样的方式建造房屋,那将是一场生态灾难。重新思考建筑的实践,不管是在这里还是在那里,都一样困难,因为我们的建筑工业的成本透明计算是错误的。它只涵盖了一部分成本,因此也只考虑了时间上被扭曲的一瞬间——相关的环境影响和真正的次级成本并没有被计算进来。”

2014年以来,劳奇在全球具有领先地位的技术大学之一教授他的知识和专业技能。他在瑞士苏黎世联邦理工学院作为客座教授,与安娜·赫里格尔合作,时间长达2年。此外,他们也都是联合国教科文组织夯土建筑教席的资深专家,该教席设立在法国格勒诺布尔国家建筑学校。

《优雅的泥土》一书的各章节松散地根据戈特弗里德·森佩尔影响广泛的作品《建筑四要素》的分类展开:“地板”——对应“土堆、台地”;“墙面”——对应“围合、编织”;“楼板”——对应“屋顶”,并以“开洞”作为补充。然而,森佩尔把“壁炉”或火源作为最重要和原始的“建筑精神要素”,并由此把其他要素作为“保护性的否定要素”或“保护壁炉火苗免受3种自然敌对要素侵犯的守护者”进行阐述。而恰恰是马丁·劳奇工作室的壁炉要素促使我产生了对其生活与建筑哲学进行探索的原动力。在1997-1998年间,我正在编辑和排版福拉尔贝格地区的建筑导览手册,莱因哈德和露特·加斯纳位于施林斯的工作室住宅就在这一地区。这座由鲁道夫·瓦格设计的住宅采用木结构框架,其间以砖块和夯土砌块填充;建筑的中心是一个立方形的采暖兼烹饪、洗涤装置,以红土建成,劳奇为它的表面打上了光滑的石蜡。这是他和加斯纳合作完成的许多作品中的第一个,在这里——我们的书籍和展览项目进行了很多年——我们一天中有许多次站在这个壁炉前喝茶或咖啡,分享点心,翻阅报纸,盛水;并且,由于我经常被获准在工作室上方的阁楼借宿,也常在夜里在这里晾衣服。总而言之,它是整个工作室的避难所和社交中心,而由于我们会无数次无意识地抚摸斑驳的红色泥土表面和它光滑、却没有被僵硬地密封起来的边缘;在它表面把玻璃杯推来推去;靠在上面的时候用臀部和膝盖触碰它;在冬天使用壁炉的时候感受它微妙的温暖,并注意到这种材料在夏天摸起来虽然有些温凉,却永远不会像混凝土、水磨石或不锈钢那样带走手掌的温度,甚至烧毛的瓷砖地面也在所难免……它就更具有避难所和社交中心的意味。许多年前,加斯纳自己描述过夯土墙在触觉上令人豁然顿悟的时刻。在他的工作室里,我通过触碰壁炉、桌子和吧台等看似表面如大理石、实则却没有其冰冷触感的建筑元素,逐渐从一个最初的怀疑论者转变为马丁的现代夯土工艺的推崇者。

劳奇总是坚持认为,一座夯土墙保存了其内部大部分的“活”水,并因此能够响应我们身体的生理特征和需求,没有任何其他材料能够做到这一点。它在这方面甚至比木材表现更为出众——具体表现在它对室内湿度的调节作用、它的透气性、以及人们抚摸它或在它表面走动时获得的触感中。夯土地面、墙面和建筑拥有与我们身体(和生理)感觉系统最理想和最积极的共鸣。他也经常在关于夯土建筑的辩论中提到“侵蚀”一词,把它从一个通常认为的负面要素转变为重要的积极因素。一方面,各种孔洞开放的材料都具有再循环的必备条件,并与人的生理特征有最佳的相关度;另一方面,由于外墙暴露在风雨中,材料特别倾向于产生表面腐蚀,而这种倾向确实能通过他发明的细部构造得到控制,这些细部都经过试验和测试——由此,没有目前施工技术所追求的过度技术化的表面密封过程,夯土材料反而能够取得一种“刻意侵蚀”的自然效果。

归结起来,与密集消耗能源的人工工业技术相比,它将引导我们面对另一种类型,它能让这种当代夯土建筑更彻底地融入有机的和无机的自然物理与化学循环过程中。“刻意侵蚀”的另一个术语也正是夯土建筑的力量所在,即这类建筑“对时间流逝痕迹‘包浆’的热爱”。无需赘述的是,显然,夯土建筑的老化过程不仅表现良好且具有尊严。在每一种条件下,它们都可以“在系统内”轻易得到修复,因此,“老化”一词并不能确切地形容其美学类型或其生命周期里的任何一个其他阶段——而所有这些都与当代建筑试图模仿机械制造与高科技产品的倾向截然相反,后者极大地消耗能源,并对天然材料进行复杂的转换加工。虽然据说它们的维护成本十分低廉,但其并非与生俱来的光鲜外表和对岁月流逝痕迹避之不及的迷人魅力却意味着,这些现代建筑并不能妥善地经历老化过程,而只是渐趋荒废。

用泥土进行建造与设计——言简意赅地说——即“低难度技术、高品质触感、高质量表现”。通过与自然达成共鸣,尤其是与更广泛的宇宙原始能量产生共振——它的影响常常激发转变的过程,夯土建筑功能与造型的精神品质与愿望在其中取得了完美的平衡。以工业化国家控制的垄断无限增长为特点的经济全球化的现实,也许会反对这种对采用立等可取且实际上成本为零的材料进行推广的思想。然而,夯土建筑的技术、生态学和美学品质——在这一卷书中得到展现,并作为人们效仿和普遍进步的基础——充分说明了它们自身。它们证实了,如果我们愿意选择,正如我们必须选择一样,则确实存在一种替代方案,即以更坚定的态度追随古老格言的召唤——文明是人类将泥土不断变得光彩夺目的过程。□

译注/Translator's Notes

1)丹麦当代艺术家/Contemporary artist in denmark

2)“乐烧”是源自日本的陶瓷烧制方法,最早出现在16世纪日本幕府时代,是桃山时代最具代表性的茶陶。最初由千利休定型,京都的陶工长次郎烧制而成/Raku is a kind of ceramic firing method which is comes from Japan.

Excerpt of Martin Rauch Refined Earth -Construction and Design with Rammed Earth, Otto Kapfinger and Marko Sauer (eds.), Edition Detail, Munich 2015, pp. 6 - 13 (fig.1,2)

Reprint by courtesy of Edition Detail, Munich

This publication tells the success story of an unorthodox thinker whose - quite literally -downto-earth approach led him to develop an eco-social stance shaped by genuine personal experience. Initially positioning himself as an "interesting" local outsider, he has gradually become a globally respected authority on ecologically advanced architecture with ideas much in demand. Martin Rauch presents three decades' worth of regional -and increasingly international - achievements in this book. His approach to basic research has been conducted bottom-up, in every sense of the word. Employing continually enhanced applications tested across varied scales, this approach has led to the creation of a fund of knowledge that has now been made available to a broad audience, along with detailed plans and explanations. This publication is not merely a platform for Rauch to present a body of work that he was able to achieve in collaboration with such well-known designers as Roger Boltshauser, Olafur Eliasson1), Herzog & de Meuron, Hermann Kaufmann, Marte.Marte, Miller & Maranta, Snøhetta, Matteo Thun, and Günther Vogt. Refined Earth is nothing less than a globally relevant educational compendium for contemporary planning and building with earthen materials.

Rauch did not discover earthen building through architecture but rather through his training and work in the late 1970s as a ceramicist, kiln builder, and sculptor. His penchant for applied craftsmanship, and for artistic autonomy in designing environments and ways of living characterized by an extreme economy of resources, was determined by his upbringing in the unpretentious, rural setting of Vorarlberg region in Austria. He was also greatly affected by foreign influences: like some of his older siblings, he volunteered for a development organization in Africa for several months in 1980. This encounter with "primitive" cultural and building technologies whose efficacy was evident in close-knit life cycles making optimal use of resources, occurred in parallel to an awareness of their brutal substitution with imported technologies from industrialized economies that were climatically and ecologically inferior, non-recyclable, and difficult to repair.

In Africa, his artistic intuition took on a global perspective: his subjective urge to work with these "poor" artisticur-materialsfoundan objective, comprehensive context within which to operate. Rauch's artisanal interest in working with clay grew to a desire to architecturally design with earth, with all its challenges and requirements. The moulding of tiles and ovens turned into a process of shaping and constructing on a large scale: transforming the earth into useful and habitable spaces. He submitted his thesis project in 1983 to Matteo Thun, director of the ceramics programme at the University of Applied Arts, Vienna. Entitled Lehm Ton Erde (Loam Clay Earth), it described the modernization of rammed earth techniques as a form of autochthonous cultural technology, be it in Africa or Europe.

Since that time, Rauch has followed a vision with universal significance that can be expressed in just a few sentences:

3 柏林忏悔教堂外景,鲁道夫·赖特曼和彼得·扎森罗特/Exterior view of the Chapel of Reconciliation, Rudolf Reitermann and Peter Sassenroth, Berlin, Germany, 1999-2000

4 忏悔教堂内景/Interior view of the Chapel of Reconciliation (3,4 摄影/Photos: Bruno Klomfar)

5 劳奇自宅外景/Exterior view of the house Rauch(摄影/Photo: Beat Bühler)

6 利口乐草药中心外景/Exterior view of the Ricola Kräuterzentrumin(摄影/Photo: Benedikt Redmann )

- Building in such a way that a house can return to "nature" after a hundred years - without leaving behind any residues or contamination - and break down into its original material constituents;

- Building in harmony with natural lifecycles and using the absolute minimum of grey energy in constructing, running and dismantling buildings;

- Building with locally available and no-cost materials - using earth taken from the construction site, as pure and unaltered as possible;

- Advancing the idea of building with earth so that it is technically and logistically up to date, in the process empowering the majority of the world's population to turn to this technique and use it to significantly improve their living conditions.

He has always had a particular interest in rammed earth techniques, a process by which the material is not clad with any further materials or surface finishes. The production process of nonplastered pisé construction, such as those Rauch also came across amongst anonymous well-preserved outbuildings in France and Germany dating from the nineteenth century, leads abruptly to its selfexpression - as in the case of low-fired unglazed ceramics. The layered construction of the wall simultaneously weaves the ornament of its own appearance. The pure structure, colour, and haptic qualities of the material are preserved and heightened during the process of moulding and compacting. With the sensitivity of the ceramicist for the composition and the physical-chemical conditions and effects of his material, Rauch set about to re-articulate the language of pisé, adapting it to meet contemporary standards and once again exposing the full sensory potential of earthen building material, whereby technical advances and enhancements went hand-inhand with formal complexity.

He was thus able to avoid, for example, the need to compensate for certain deficiencies in traditional pisé techniques by adding cement, as this would diminish some of the essential qualities of earthen buildings, such as its ease of recyclability, its breathability, or its minimal entropy. Instead, he sought to improve natural material mixtures, optimized the compaction process and the shape of the formwork, and introduced layers of reinforcement to systematically develop traditional techniques without abandoning their basic structural principles. Tools, procedures, and types of formworks were developed from scratch and then evaluated and refined; test walls were constructed and the practical experience gathered in the process was immediately fed into the next series of experiments.

Rauch made his first forays into building in 1982, in the form of small projects for family members and friends who were open to experimentation, collaborating with local architects such as Robert Felber and Rudolf Wäger. The house in Schlins constructed for his elder brother Johannes - a farmer, master locksmith, and graduate of the Academy of Fine Arts, Vienna, who had been involved for many years in development projects in Zambia, Uganda, and Tanzania - was the very first modern timber and earth construction in the Vorarlberg region. The Chapel of Reconciliation in Berlin-Mittere presents a clear turning point in his practice (fig.3-4). In accordance with plans drawn up by the Berlin-based team of Peter Sassenroth and Rudolf Reitermann, a public space for reflection was gradually erected from 1999 to 2000 on the foundations of a church located in the former "death strip" that had been dynamited to make way for the Berlin Wall. The 7-meter-high oval of the chapel, with a floor and altar of rammed earth and capped with a timber roof, was the first new construction in Germany to utilize pisé techniques in hundreds of years and required its own building permit procedure. As there are no norms or building regulations for load-bearing rammed earth walls, permit offices and engineers found themselves in an unexplored territory - one of several requirements was a seven-fold increase in the normal static safety factor! The external monitoring and scientific supervision that had also been stipulated was assumed by the Technical University of Berlin. After countless test procedures, test specimens, and a plethora of expert reports had been enlisted in a process lasting several years, this age-old, global building technique could finally be integrated into -and approved for - our technological age.

Martin Rauch may make fundamental demands when it comes to ecological standards, but the constructional and artistic flair evident in all his built works does not evoke a sense of fundamentalism. After completing the high-profile chapel in Berlin and a large building for Basel Zoo, a three-storey house and atelier he designed for himself in Schlins, in collaboration with Roger Boltshauser, represented a new synthesis of all the experience he had accumulated up to that point (fig.5, page 52). It was here that modern earthen building was finally able to separate itself from naïve-ecological clichés and move towards a technical maturity and formal clarity that, even a few years previously, would have seemed unimaginable. From the foundations that extend up into the walls to the floors, slabs, staircase, and window and door openings, Rauch had control over every element - even down to the manifold use of tiles, the water basins, the form of the hearth, and the wall and floor finishes. Every detail of the threestorey building - a product of the teamwork with the congenial Roger Boltshauser - is uncompromisingly a part of his vision, emphasizing the full breadth of physical and aesthetic qualities, from the coarseness of the earth to the porcelain-like delicacy.

This building has garnered national and international awards, been published worldwide, and opened the doors to further projects of greater dimensions. When I was able to step inside the building shortly before its completion in 2008, it was quite a shock - a positive kind of shock! I had been familiar with Martin's work since 1996 - 1997 upon beginning my research for the architecture guide for Vorarlberg region. In 2001, we collaborated on the trilingual publication Rammed Earth for a leading specialist publishing house - this represented a first large-scale summary of his agenda. But when I firstwitnessed this quantum leap in quality manifested by the house and atelier he had built for his family, I could only gape with amazement. From the exterior and on the ground floor, everything seemed familiar and as I would have anticipated. But on ascendance to the main floor, a sensational shift occurred. Coming up from the coarse-grained, raw-earth atmosphere below, I emerged into ivory-coloured, gleaming rooms, alternating between the light-coloured, vibrant grey of the waxed rammed earth floors, the bright casein finish of the window apertures and sliding door panels, treated with linseed oil and wax, and the velvety, tactile earth plaster of the walls (which act as hypocausts) and ceilings. On the third floor, comprising the bedrooms, office, and bathrooms, this process of refinement was further elaborated to produce an alabaster-like effect in the earth. This is achieved in no small part by the raku2) technique applied to the fired floor and wall tiles, with their satin-sheened, light-and-dark ornamentdeveloped by Martin's wife, the ceramic artist Marta Rauch-Debevec, and his son Sebastian Rauch, who trained as a graphic designer.

Rauch describes a central plank of his technical ethos as follows: "The envelope that surrounds us should be able to breathe and diffuse in the same way as our bodies. My buildings are therefore deliberately not encapsulated, sealed, or made smooth with synthetic or high-density, energyintensive materials; rather, they are assembled and finished in raw form, like sushi - left uncooked! The entire building substance remains permeable, meaning that it is sufficiently resistant to the demands of usage and maintenance and minimally resistant to long-term degradation and the recycling process." Roger Boltshauser adds, "The archaic, direct workmanship and clear architectural language resulted in a house that melds extremely well with the landscape. In many aspects, it represents a true broadening of the horizon. These principles ought to be the basis of a universal strategy for future architectural design." This project represents a concrete expression of an almost inconceivable possibility: the chance not only to offset the division of labor, knowledge and material coincidence in architecture, a compartmentalization that dominates our high-tech, specialized world, but also to do so using the lowest level of entropy imaginable to satisfy our requirements for building, dwelling, and living appropriately - providing a globally relevant paradigm in the process.

For more recent international projects with Herzog & de Meuron, Snøhetta, and others, a new wave of innovation was both necessary and of vital importance - including the adaptation of manually rammed earth techniques to suit the demands of industrial-scale production, prefabrication, logistical requirements and costs calculations of complex, large-scale construction projects. Rauch developed his own machine to address this challenge - a robot that automatically feeds material into the formwork and compacts it mechanically. This system can be used to produce formwork lengths of 50~80m in variable thicknesses. After removing this mould, the rammed course - one full length of the formwork -can be cut into elements of any size. This is primarily dependent on how the pieces can be transported, and in particular, on the load-bearing capacity of the crane, which is usually a maximum of five tons. This technique has proved its worth in the recent construction of the Ricola Kräuterzentrumin Laufen (fig.6, page 82) as well as the visitor center at the Swiss Ornithological Institute (page 88).

Rauch has long served as an lecturer and has led workshops in Europe, Asia, and Africa. Perhaps the most far-reaching fruits of his range of small and increasingly larger-scale built works are not so much the many beautiful single-family homes in the architecturally rich Vorarlberg region or the spectacular collaborations with internationally renowned architectural visionaries in various locations, but rather his consulting work for academic and prototype projects in South Africa - in the townships of Johannesburg - or in Bangladesh. Here his expertise has supported, and continues to support, people who truly need construct their own simple, low-cost, climatically appropriate buildings by teaching effective techniques, thus promoting a sustainable alternative to exported methods of building, one that is not dependent onlarge-scale technologies and industry-compatible visions of "foreign aid". In Bangladesh, a land undergoing enormous population expansion and with disastrous housing and living conditions, Rauch received the 2007 Aga Khan Award for Architecture and the 2008 World Architecture Community Award for technical consultancy and support on school and housing projects developed together with architect Anna Heringer: "The big step forward was being able to show people how they can use the earth from the construction site to build low-cost two-storey structures themselves - without any additional technology - and create spaces that are of the highest quality climatically. We managed this via public workshops and using the structures that we built together as an example. As timber is rare in the region, we were forced to use concrete for the slabs in the end. But this is just a fraction of the amount that is utilized for new residential projects there. I have frequently attended conferences in the southern hemisphere, where the idea gets pushed that earth building can be improved with cement in order to better integrate it into established construction industry practices. The only problem is that, to earn a sack of cement, a laborer now has to work three times longer than he did ten years ago, because demand is so high. The really political aspect of pure earth building is that it can be implemented anywhere fully independently of lobbies, share prices, and industrial price controls, with simple craftsmanship being used to construct high-quality, ecologically appropriate buildings. In our part of the world, where labor is particularly expensive, manually crafted earth building is practically a luxury product. In countries where labor is readily available, for example, in Egypt, my house in Schlins would have been approximately 60 per cent cheaper and could even be a kind of standard dwellings! If we were to keep building all around the world inthe same way we have in the industrialized nations, it would be an ecological catastrophe. Rethinking practices is just as difficult here as it is there, because the cost transparency of our construction industry is incorrect. It only captures a brief and therefore distorted moment in time: the associated environmental impact and the real secondary costs are not taken in consideration in the calculations."

Since 2014, Rauch has communicated his knowledge and expertise at one of the world's leading technical universities. His guest professorship at the ETH Zurich, in collaboration with Anna Heringer, lasts two years. Furthermore, they both serve as honorary professors at the UNESCO Chair of Earthen Architecture, which is based at the Grenoble National School of Architecture.

The chapters of Refined Earth loosely follow the classifications in Gottfried Semper's seminal text The Four Elements of Architecture: FLOOR - corresponds to Mound, Terrace; WALL - corresponds to Enclosure, Weaving; SLAB - corresponds to Roof, supplemented by the category OPENING. However, Semper identified the HEARTH, or tamed fire, as the first and original "moral element of architecture" in order to categorize the other elements as "protecting negations", or "defenders of the hearth's flame against the three hostile elements of nature." It was precisely this sort of hearth element from Martin Rauch's workshop that prompted my initiation into his philosophy of living and building. In 1997/98, I was working on the editing and layout of my architectural guide to Vorarlberg with Reinhard and Ruth Gassner out of their studio house in Schlins. The house designed by Rudolf Wägerwas executed in timber framing, infilled with both bricks and rammed earth components; at its center was a cubic heating-cooking-washing element of reddish-brown earth, which Rauch had constructed with a smoothed wax finish. In this, the first ofmany collaborations with Gassner - our book and exhibition projects spanned many years - we stood at the hearth several times a day drinking tea and coffee, sharing snacks, leafing through newspapers, drawing water, and, since I was often allowed to spend the night in the lofted roof space above the studio, laying out my clothes in the evening. In short, it was the haven and social heart of the atelier, even more so because we would subconsciously touch the mottled red, earthen surfaces and the smooth yet not rigidly sealed edges of this element countless times; pushed glasses across its surface; touched it with our hips and knees as we leaned against it; sensed its subtle warmth in winter when the oven was in use, and noticed that in summer touching this material felt slightly cool, yet never extracted warmth from the hands, as a concrete, terrazzo, or stainless-steel surface, or even a sintered tile floor, certainly would. Many years previously, Gassner had himself described the experience of his tactile "aha" moment with rammed earth walls. In his atelier, through the exposure to the hearth, table, and bar elements that looked like marble but did not have its cold quality, I too gradually transformed from an initial sceptic into an advocate for Martin's contemporary rammed earth artistry.

Rauch always argues that a rammed earth wall retains a large portion of "living" water inside it and therefore corresponds, like no other material, and even more so than wood, to the physiological qualities and needs of our physical beings -expressed in its regulation of room humidity, in its breathability, and in its haptic quality when touched or walked on. Earth floors, walls, and buildings have the most ideal, active resonance with the physiological systems of our physical (and psychological) senses. He also frequently discusses the term EROSION in the debate on earth building, turning it from a commonly accepted negative into an emphatic positive. On the one hand, openpored materials are a prerequisite for recyclability and also provide the optimal correlation to human physiology; on the other, surface erosion that exterior walls exposed to wind and rain are particularly prone to can indeed be well controlled by the tried and tested details he developed - and then, instead of the over-technologized hermetic sealing pursued by current construction practices, a natural "calculated erosion" can be achieved.

This leads us, in conclusion, towards another category, one which, in comparison to the energyintensive artificiality of industrialized technologies, integrates this kind of contemporary earth building much more thoroughly into physical and chemical cycles of organic and inorganic nature. Another term for calculated erosion, which is the strength of building with earth, could be the PATINOPHILIA of this kind of architecture. Without going into further detail here, it is clear that earth buildings do not just age well and with dignity. In each and every condition, they can easily be repaired in the system, so that "aging" does not actually describe an aesthetic category or any other stage of their life cycle - and all of this is diametrically opposed to the tendency of contemporary architecture to emulate the model of mechanized and high-tech production, with its high levels of energy expenditure and complex transformations of natural substances. Allegedly lowmaintenance, their extrinsic brilliancy and patinaphobic glamour means that these modern buildings cannot age but only fade into obsolescence.

Building and designing with earth is - to put it succinctly - "low-tech + high-touch + highperformance." The ethos and Eros of using and shaping are in perfect balance, in resonance with our nature, in particular, as well as with the larger Eros nature of the cosmos in general, whose influence actuates constant transformation. The reality of economic globalization, characterized by the ever-increasing monopolies controlled by the industrialized nations, perhaps argues against a concept that cultivates resources which are readily available at practically no cost (!). However, the technical, ecological, and aesthetic qualities of building with earth - presented in this volume and offered as a basis for emulation and universal advancement - speak for themselves. They substantiate the fact that there is an alternative, if we choose, as we must, to follow the call of an ancient dictum in more determined fashion: Civilization is the sustainable transformation of the earth into a relief at the disposal of humankind.□

Use the Earth! The Life and Work of Martin Rauch

Otto Kapfinger

Translated by XU Zhilan

作家、建筑评论家

2016-09-09