阿司匹林剂量对高龄老年患者血小板功能的影响

冯雪茹,刘梅林,刘 芳,范 琰,田清平

(北京大学第一医院老年内科,北京 100034)

·论著·

阿司匹林剂量对高龄老年患者血小板功能的影响

冯雪茹,刘梅林△,刘 芳,范 琰,田清平

(北京大学第一医院老年内科,北京 100034)

目的:观察阿司匹林100 mg/d更换为40 mg/d后血小板聚集率变化,评估高龄老年患者对阿司匹林的反应性,分析阿司匹林相关出血的影响因素。方法:入选537例服用阿司匹林100 mg/d(7 d以上)的年龄≥80岁老年患者,根据心血管疾病风险、出血风险评估和花生四烯酸诱导的血小板聚集率(arachidonic acid-induced platelet aggregation,AA-Ag),100例患者更换为阿司匹林40 mg/d。观察阿司匹林更换为40 mg/d的患者AA-Ag水平及变化,以及3个月内出血情况和上消化道症状变化。结果:537例高龄老年患者服用阿司匹林100 mg/d时的AA-Ag平均10.27%±5.34%(0.42%~28.78%),下四分位数为5.80%;阿司匹林40 mg组减量前AA-Ag平均为5.00%±2.32%,其中71.00%的患者AA-Ag<5.80%。40 mg组患者黑便或便潜血阳性、其他部位出血、上消化道症状和消化道出血史明显高于100 mg组。服用阿司匹林40 mg/d后AA-Ag增加至11.21%±4.95%(2.12%~28.84%),AA-Ag≥20%者仅为5.00%。多因素分析显示,阿司匹林40 mg AA-Ag与100 mg AA-Ag、体重指数、血小板数正相关,阿司匹林40 mg组中有消化道出血症状的患者比率由减量前的12.00%降低至5.00%,其他部位出血由26.00%降低至8.00%,上消化道症状改善。结论:阿司匹林40 mg/d能够有效抑制高龄老年患者的血小板聚集;100 mg/d改为40 mg/d,患者出血风险降低、上消化道不适症状改善。

阿司匹林;血小板聚集;老年人,80以上;出血;剂量

阿司匹林是临床广泛应用的抗血小板药物,能够减少心血管事件及死亡率,但高龄老年患者容易发生阿司匹林相关出血,导致预后不良[1]。近年的研究表明,对阿司匹林治疗的反应性个体差异大,高反应者出血的风险增加[2],对于高龄老年患者,如何调整阿司匹林剂量尚无可靠评价方法。本研究旨在评估高龄老年患者对阿司匹林的反应性,观察阿司匹林100 mg/d更换为40 mg/d后血小板聚集率变化,并分析阿司匹林相关出血的影响因素。

1 资料与方法

1.1 研究对象

入选2008年5月至2014年9月在北京大学第一医院老年内科住院的年龄≥80岁、服用肠溶阿司匹林(拜耳医药保健有限公司)100 mg/d的老年患者537例,排除标准:(1)血小板计数小于100×109/L;(2)血液系统疾病;(3)使用血小板糖蛋白(glycoprotein,GP)Ⅱb/Ⅲa拮抗剂、华法林、达比加群酯、利伐沙班或非甾体类抗炎药;(4)肝脏疾病;(5)有阿司匹林使用禁忌证。入院后由临床医生根据心血管疾病危险因素[3-4]、阿司匹林出血危险[5]、血小板聚集率进行评估,其中,437例持续服用阿司匹林100 mg/d(阿司匹林100 mg组),其余100例患心血管疾病风险低、出血危险高、血小板聚集率低的患者,阿司匹林剂量由100 mg/d减为肠溶阿司匹林(北京曙光药业)40 mg/d(阿司匹林40 mg组)。阿司匹林40 mg组和100 mg组的患者年龄分别为(83.83±3.51)岁(80~94岁)和(83.08±2.77)岁(80~94岁),女性患者分别占38.00%(38例)和25.63%(112例)。

1.2 血小板聚集率检测

服用阿司匹林100 mg/d或减量为40 mg/d至少7 d后检测花生四烯酸诱导的血小板聚集率(arachidonic acid-induced platelet aggregation,AA-Ag)。患者空腹6 h以上,取静脉血3 mL至109 mmol/L枸橼酸钠抗凝管中混匀,150×g离心10 min制备富含血小板血浆,1 500×g离心10 min制备乏血小板血浆。AA-Ag检测[6]:使用LBY-NJ4型血小板聚集仪(北京普利生公司)检测乏血小板血浆和富含血小板血浆中血小板的相对浓度数值,将富含血小板血浆中加入0.5 mmol/L花生四烯酸(美国Sigma公司),采用光学透射比浊法检测血小板最大聚集率,在采血后2 h内完成检测。本研究分别统计了阿司匹林100 mg AA-Ag和40 mg AA-Ag,前者包括100 mg组和40 mg组减量前的数据,后者为40 mg组减量后的数据。

1.3 病例资料采集

采集患者身高、体重、心血管疾病危险因素、疾病诊断、联合用药及血生化、血常规、超敏C反应蛋白、纤维蛋白原等资料。计算体重指数(body mass index,BMI)体重(kg)/身高(m)2,BMI≥28.0 kg/m2为肥胖,24.0~27.9 kg/m2为超重,18.5~24.0 kg/m2为体重正常,<18.5 kg/m2为体重过低;根据改良肾脏病饮食(modification of diet in renal disease,MDRD)公式计算出肾小球滤过率估算值(estimating glomerular filtration rate,eGFR)[7]。收集出血及相关信息,包括黑便、大便潜血阳性及其他部位出血(皮肤瘀斑、牙龈出血、球结膜出血、血尿、鼻出血)、上消化道症状(胃食管反流、上腹疼痛、消化不良等)、消化道出血史、消化性溃疡史等。

门诊随访观察3个月内消化道出血(黑便或大便潜血阳性)、其他部位出血及上消化道症状的情况,根据心肌梗死溶栓治疗临床试验(thrombolysis in myocardial infarction,TIMI)出血分级标准[8],临床显性出血时血红蛋白浓度下降≥50 g/L为大出血,血红蛋白浓度下降30~50 g/L为小出血,血红蛋白浓度下降<30 g/L为轻微出血。

1.4 统计学分析

仅对阿司匹林40 mg AA-Ag进行相关性分析及单因素、多元线性回归分析。应用SPSS 16.0软件进行统计分析,计量资料以均数±标准差表示,两组间比较采用成组t检验,多组间比较采用单因素方差分析,两两比较采用LSD法,各计量指标与AA-Ag的关系应用Pearson相关分析;计数资料以频数及百分率表示,组间比较应用χ2检验;调整剂量前后计量资料比较采用配对t检验,计数资料比较采用McNemar检验。根据单因素分析结果选择影响AA-Ag的因素进行多元线性回归分析,P<0.05为差异有统计学意义。

2 结果

2.1 临床特征

阿司匹林40 mg组和100 mg组的临床特征见表1, 40 mg组合用硝酸酯类药物及氯吡格雷者均低于100 mg组(P<0.05);40 mg组患冠心病的比率低于100 mg组(51.00%vs.62.93%,P<0.05), 且未见急性冠状动脉综合征(acute coronary syndrome,ACS)或经皮冠状动脉介入治疗(percutaneous coronary intervention,PCI)术后≤1年者,而100 mg组中患有ACS或PCI术后≤1年者分别占24.26%和10.07%。

阿司匹林40 mg组中出现黑便、便潜血阳性或其他部位出血的患者分别占12.00%(12/100)和26.00%(26/100), 高于100 mg组的3.43%(15/437)和14.87%(65/437),二组均为轻微出血;其中,合用氯吡格雷者发生出血占54.55%(12/22),高于未用氯吡格雷者的33.33%(26/78)(P<0.01)。40 mg组中有上消化道症状、消化道出血史和消化性溃疡史者分别占59.00%(59例)、13.00%(13例)和14.00%(14例),其中51.00%(51/100)的患者合并≥2项出血或危险因素,明显高于100 mg组的19.91%(87/437);80.00%的患者存在消化道异常表现,均使用质子泵抑制剂或H2受体拮抗剂。

表1 阿司匹林40 mg组与100 mg组临床特征比较Table 1 Comparison of clinical characteristics between aspirin 40 mg group and 100 mg group

BMI, body mass index; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; ACE, angiotensin converting enzyme; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; AA-Ag, arachidonic acid-induced platelet aggregation.

2.2 阿司匹林反应性

537例患者阿司匹林100 mg AA-Ag平均为10.27%±5.34%(0.42%~28.78%),下四分位数为5.80%;其中36例≥20%,占6.70%。阿司匹林40 mg组减量前的AA-Ag平均为5.00%±2.32%(0.42%~11.27%),明显低于100 mg组[11.24%±5.31%(0.50%~28.78%),P<0.01],且有71.00%(71/100)低于下四分位数,而阿司匹林100 mg组的AA-Ag仅有17.62%(77/437)低于下四分位数。

40 mg组阿司匹林减量后的AA-Ag平均为11.21%±4.95%(2.12%~28.84%), 其中5.00%(5例)≥20%、15.00%(15例)<5.80%,较阿司匹林减量前升高6.21%±3.92%(1.36%~21.56%),差异有统计学意义(P<0.001,表2)。

表2 40 mg组阿司匹林减量前后临床特征比较(n=100)Table 2 Comparison of characteristics before and after the switch in aspirin 40 mg group (n=100)

Abbreviations as in Table 1.

2.3 BMI与阿司匹林40 mg AA-Ag的相关性分析

相关分析显示,40 mg组中BMI与阿司匹林减量后的AA-Ag正相关,r值为0.30(P<0.01)。阿司匹林40 mg组中体重正常或过低者、超重者和肥胖者分别为57例、30例和13例,肥胖者AA-Ag(15.89%±4.73%)明显高于体重正常或过低者(9.54%±3.64%,P<0.01)及超重者(12.35%±5.65%,P<0.05);肥胖者中AA-Ag≥20%者占15.38%(2/13),高于超重者[1.0%(3/30),P<0.05]和体重正常或过低者(0/57,P<0.05);体重正常或过低者AA-Ag<5.80%者占19.30%(11/57),高于超重者[13.33%(4/30),P<0.05]和肥胖者(0/13,P<0.05)。肥胖者阿司匹林减量后的AA-Ag升高值为9.66%±4.62%,明显高于体重正常或过低者(4.68%±2.45%,P<0.01)及超重者(7.61%±4.47%,P<0.01)。

2.4 阿司匹林40 mg AA-Ag的影响因素

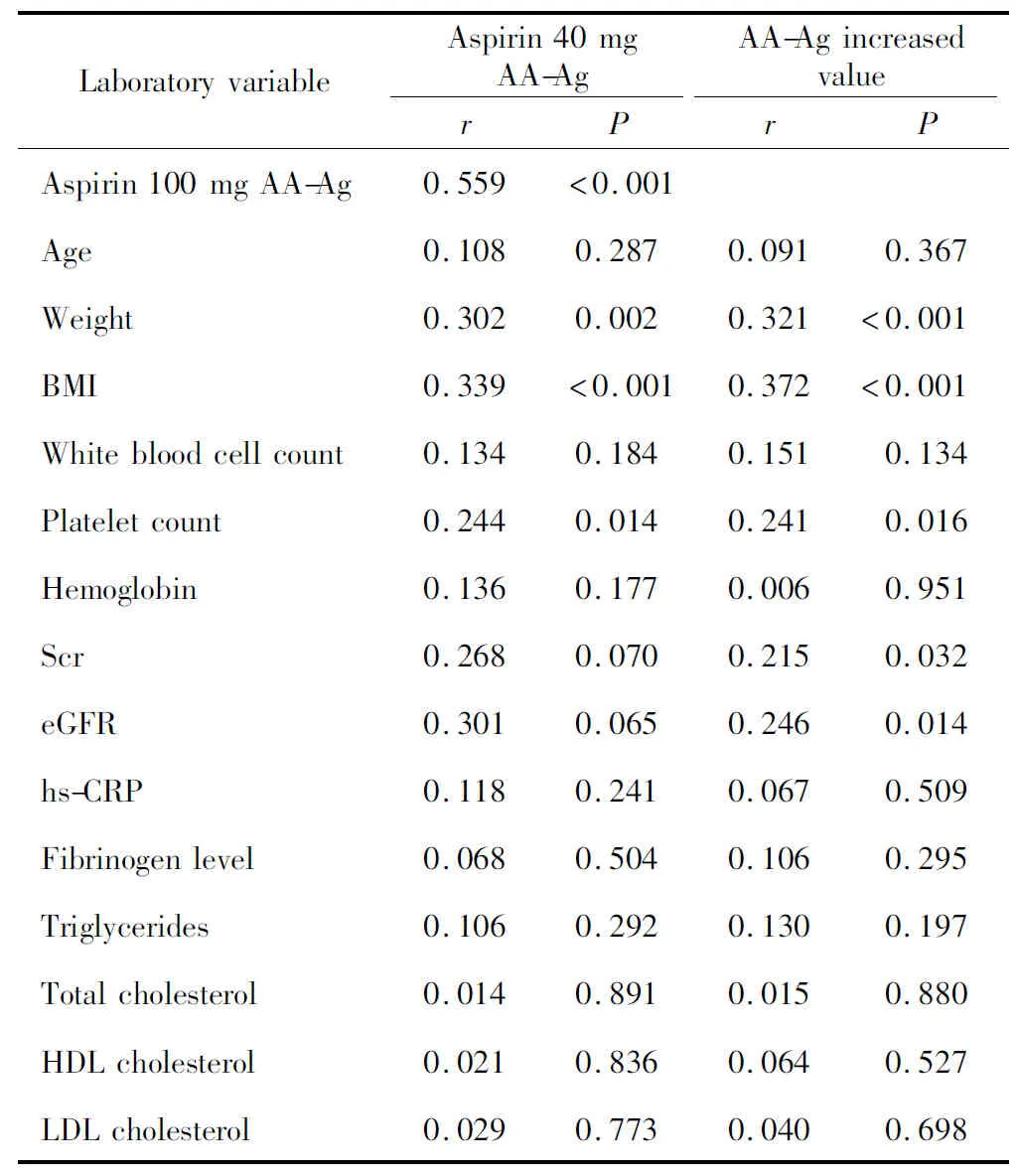

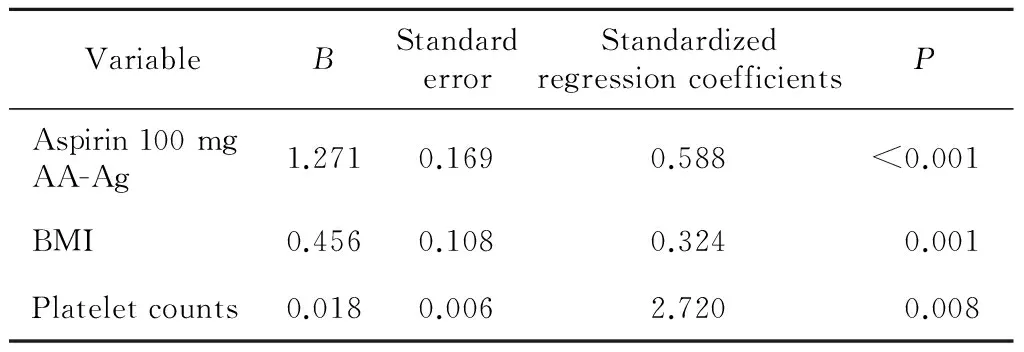

单因素分析显示,40 mg组中糖尿病、体重≥80.0 kg或肥胖的患者阿司匹林减量后的AA-Ag分别高于非糖尿病、体重<80.0 kg或非肥胖的患者(表3),体重、BMI、血小板数、减量前的AA-Ag与减量后的AA-Ag正相关(表4)。多元线性回归分析显示,阿司匹林减量前的AA-Ag、BMI及血小板数均为减量后AA-Ag水平的影响因素(表5)。

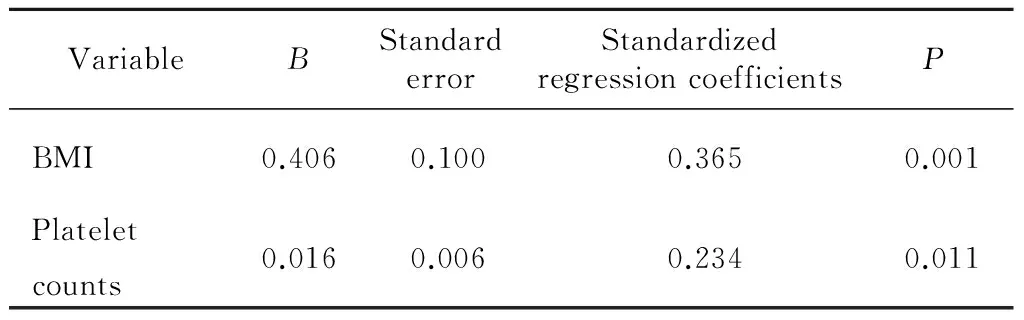

单因素分析显示,体重≥80.0 kg或肥胖的患者在阿司匹林减量后AA-Ag升高值明显高于体重<80.0 kg或非肥胖的患者(表3),体重、BMI、血小板数与AA-Ag升高值正相关,eGFR与AA-Ag升高值负相关(表4)。多元线性回归分析显示,BMI、血小板数为AA-Ag升高值的影响因素(表6)。

表3 阿司匹林40 mg AA-Ag与各临床指标的关系(n=100)Table 3 Correlation between the clinical variables and AA-Ag in aspirin 40 mg group (n=100)

Abbreviations as in Table 1.

表4 阿司匹林40 mg AA-Ag与各实验室指标的相关性分析(n=100)Table 4 Laboratory variables and AA-Ag in aspirin 40 mg group (n=100)

Scr,serum creatinine; eGFR, estimating glomerular filtration rate; hs-CRP, high sensitivity C-reactive protein; HDL, high density lipoprotein; LDL,low density lipoprotein; Other abbreviations as in Table 1.

表5 阿司匹林40 mg AA-Ag影响因素的多元线性回归分析(n=100)Table 5 Multiple variable analysis between aspirin 40 mg AA-Ag and variables (n=100)

Abbreviations as in Table 1.F=22.622,P<0.01,R2=0.448.

表6 40 mg组阿司匹林减量后AA-Ag增量影响因素的 多元线性回归分析(n=100)Table 6 Multiple variable analysis between AA-Ag increased value and variables in aspirin 40 mg group (n=100)

Abbreviations as in Table 1.F=9.298,P<0.01,R2=0.225.

2.5 随访结果

483例患者完成随访(包括阿司匹林40 mg组的全部100例患者), 54例失访。阿司匹林100 mg组的患者消化道出血发生率为2.61%(10/383),其中2例为小出血、8例为轻微出血;40 mg组的消化道出血发生率由阿司匹林减量前的12.00%(12/100)降低至减量后的5.00%(5/100), 5例患者均为轻微出血且均合用了氯吡格雷,2例AA-Ag<5.80%,其他部位出血发生率也由26.00%(26/100)降低至8.00%(8/100),上消化道症状发生率由59.00%(59/100)减少至21.00%(21/100)(表2)。

3 讨论

研究表明,年龄是阿司匹林相关出血的重要危险因素,高龄老年患者应用阿司匹林后的出血风险明显增加[6],严重影响了阿司匹林降低心血管事件的获益。2014年发表在JAMA的日本一级预防研究显示,对14 464例60~85岁老年患者应用阿司匹林(100 mg/d)的治疗显著增加了颅外出血的风险,并未降低包括死亡等的联合终点事件[9]。因此,对于老年患者尤其是高龄老年患者,使用阿司匹林需权衡心血管获益和出血风险[4],坚持个体化治疗原则,最大限度降低出血并发症,使其能够从阿司匹林治疗中获益。目前临床上高龄老年人群多采用一般人群的阿司匹林治疗方案,但适用于高龄老年患者的阿司匹林使用剂量或最小有效剂量仍缺乏充分的临床试验证据。

本研究中,537例高龄老年患者应用阿司匹林100 mg/d时,AA-Ag为0.42%~28.78%,个体差异很大,部分患者对阿司匹林的反应性高,提示阿司匹林100 mg/d并不一定适用于所有高龄老年患者。

近年的研究表明,抗血小板药物高反应者发生消化道、颅内等部位出血的风险更高[10-12];抗血小板药物出血预测研究(predictor of bleedings with antiplatelet drugs study,POBA)也表明,血小板活性过低是PCI后1个月内非穿刺部位出血的独立预测指标[13];我们既往对老年人群阿司匹林反应性的研究也同样提示,阿司匹林高反应可能与消化道出血有关[14]。对血小板聚集率过低、出血风险高的患者可减少阿司匹林剂量或调整抗血小板药物,以减少出血的风险[3]。

大量临床试验表明,阿司匹林剂量75~150 mg/d是长期心血管获益的有效剂量,但多数临床研究中并未纳入高龄老年患者;有研究显示,阿司匹林40~50 mg/d即能抑制78%以上的血栓素A2生成[15-16];此外,荷兰短暂性脑缺血发作试验(Dutch transient ischemic attacktrial,Dutch TIA)、Ranke等研究以及抗栓试验协作组(Antithrombotic Trialists’ Collaboration,ATT)荟萃分析显示,阿司匹林剂量30~50 mg/d时降低心血管事件和心血管死亡的作用不劣于大剂量阿司匹林[17-19]。由于阿司匹林的出血发生率随剂量增加而升高,为降低出血发生率,本研究将出血风险高、心血管风险相对低的100例高龄老年患者使用阿司匹林的剂量由100 mg/d减少至40 mg/d,在减量前该100例患者中有71.00%AA-Ag过低,低于下四分位数5.80%。

本研究显示,阿司匹林40 mg/d用于出血风险高的高龄老年患者,可有效抑制大多数患者的血小板聚集并降低出血风险。阿司匹林40 mg/d时的AA-Ag平均为11.21%,95%的患者AA-Ag<20%。对阿司匹林40 mg/d时的AA-Ag影响因素进行分析,结果显示,对阿司匹林100 mg/d高反应的患者改用40 mg/d后仍能有效抑制血小板聚集。在使用阿司匹林40 mg/d的患者中,体重正常或过低者AA-Ag均<20%,而肥胖患者中15.38%表现为AA-Ag≥20%,提示选择阿司匹林剂量时应考虑BMI,不能简单地将阿司匹林疗效不足归因于阿司匹林抵抗。本研究显示,根据患者出血风险、阿司匹林治疗后血小板聚集率评估,将有助于指导高龄老年患者选择阿司匹林治疗剂量。

此外,本研究还显示,阿司匹林由100 mg/d减至40 mg/d后,AA-Ag有所升高,消化道和其他部位出血的发生率降低,消化道不适症状改善。3例发生消化道出血的患者联合使用阿司匹林40 mg/d及氯吡格雷治疗,其中2例AA-Ag低于下四分位数,提示阿司匹林40 mg/d的患者合用氯吡格雷时应警惕出血风险。

受条件限制,本研究入选病例数较少,且鉴于高龄老年患者病情复杂、影响因素多,难以得出可靠结论。此外,由于本研究中调整至阿司匹林40 mg/d的患者心血管风险相对低,未与阿司匹林100 mg/d组进行心脑血管事件的对比观察。期待启动老年人群使用阿司匹林的大规模、多中心临床研究。

综上,本研究表明,监测血小板聚集率对于指导高龄老年患者调整阿司匹林剂量有临床价值,阿司匹林40 mg/d用于出血风险高、阿司匹林高反应性的高龄老年患者,可有效抑制血小板聚集并降低出血风险,改善消化道症状。

[1]Capodanno D, Angiolillo DJ. Antithrombotic therapy in the elderly[J]. J Am Coll Cardiol, 2010, 56(21): 1683-1692.

[2]Gorog DA, Fuster V. Platelet function tests in clinical cardiology: unfulfilled expectations[J]. J Am Coll Cardiol, 2013, 61(21): 2115-2129.

[3]US Preventive Services Task Force. Aspirin for the prevention of cardiovascular disease: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force re-commendation statement[J].Ann Intern Med, 2009, 150(6): 396-404.

[4]中华医学会心血管病学分会, 中华心血管病杂志编辑委员会. 阿司匹林在动脉硬化性心血管疾病中的临床应用:中国专家共识(2005)[J]. 中华心血管病杂志, 2006, 34(3): 281-284.

[5]Bhatt DL, Scheiman J, Abraham NS. ACCF/ACG/AHA 2008 expert consensus document on reducing the gastrointestinal risks of antiplatelet therapy and NSAID use: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Task Force on Clinical Expert Consensus Documents[J].J Am Coll Cardiol, 2008, 52(24): 1502-1517.

[6]李涛,屈晨雪, 王建中. 光学比浊法血小板聚集试验的标准化研究[J]. 中国实验诊断学, 2010, 14(12): 2041-2043.

[7]Ma YC, Zuo L, Chen JH, et a1. Modified domemlar filtration rate estimating equation for Chinese patients with chronic kidney disease[J]. J Am Sec Nephrol, 2006, 17(10): 2937-2944.

[8]Wiviott SD, Braunwald E, McCabe CH, et al.Prasugrel versus clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes[J].N Engl J Med, 2007, 357(20): 2001-2015.

[9]Ikeda Y, Shimada K, Teramoto T, et al.Low-dose aspirin for primary prevention of cardiovascular events in Japanese patients 60 years or older with atherosclerotic risk factors: a randomized clinical trial[J]. JAMA, 2014, 312(23): 2510-2520.

[10]Cuisset T, Cayla G, Frere C, et al. Predictive value of post-treatment platelet reactivity for occurrence of post-discharge bleeding after non-ST elevation acute coronary syndrome. Shifting from antiplatelet resistance to bleeding risk assessment?[J]. Euro Intervention, 2009, 5(3): 325-329.

[11]Cuisset T, Frere C, Quilici J, et al. Post-PCI fatal bleeding in aspirin and clopidogrel hyper responder: shifting from antiplatelet resistance to bleeding risk assessment?[J].Int J Cardiol, 2010, 138(2): 212-213.

[12]Tsukahara K, Kimura K, Morita S, et al. Impact of high-responsiveness to dual antiplatelet therapy on bleeding complications in patients receiving drug-eluting stents[J].Circ J, 2010, 74(4): 679-685.

[13]Cuisset T, Grosdidier C, Loundou AD, et al. Clinical implications of very low on-treatment platelet reactivity in patients treated with thienopyridine: The POBA study (predictor of bleedings with antiplatelet drugs)[J]. JACC Cardiovasc Interv, 2013, 6(8): 854-863.

[14]冯雪茹,刘梅林,刘芳, 等. 老年患者阿司匹林反应性及影响因素分析[J]. 中华心血管病杂志, 2011, 39(10): 925-928.

[15]Patrono C. Aspirin as an antiplatelet drug[J]. N Engl J Med, 1994, 330(18): 1287-1294.

[16]De Caterina R, Giannessi D, Boem A, et al. Equal antiplatelet effects of aspirin 50 or 324 mg/day in patients after acute myocardial infarction[J]. Thromb Haemost, 1985, 54(2): 528-532.

[17]The Dutch TIA Trial Study Group. A comparison of two doses of aspirin (30 mgvs. 283 mg a day) in patients after a transient ischemic attack or minor ischemic stroke[J].N Engl J Med, 1991, 325(18): 1261-1266.

[18]Ranke C, Creutzig A, Luska G,et al. Controlled trial of high-versus low-dose aspirin treatment after percutaneous transluminal angioplasty in patients with peripheral vascular disease[J]. Clin Invest Med, 1994, 72(9): 673-680.

[19]Antithrombotic Trialists’ Collaboration.Collaborative meta-analysis of randomised trials of antiplatelet therapy for prevention of death, myocardial infarction, and stroke in high risk patients[J].BMJ, 2002, 324(7329): 71-86.

(2015-06-23收稿)

(本文编辑:赵 波)

Dose-response of aspirin on platelet function in very elderly patients

FENG Xue-ru, LIU Mei-lin△, LIU Fang, FAN Yan, TIAN Qing-ping

(Department of Geriatrics, Peking University First Hospital, Beijing 100034, China)

Objective: To assess the consequences of switching aspirin dosage from 100 mg/d to 40 mg/d on cardiovascular benefit, bleeding risk and platelet aggregation in very elderly patients. Methods: Arachidonic acid induced platelet aggregation(AA-Ag) was measured in 537 patients aged 80 or older treated with aspirin (100 mg/d). In the study, 100 patients with low on-treatment platelet aggregation and at high risk of bleeding and low risk of cardiovascular events, were switched to aspirin (40 mg/d) and their platelet aggregation was measured again 7 days later.Their bleeding and upper gastrointestinal symptoms were also recorded in following 3 months. Results: The study observed a heterogeneous distributed aspirin 100 mg/d AA-Ag (range: 0.42% to 28.78%)in the 537 very elderly patients.Aspirin 100 mg/d AA-Ag before the switch in aspirin 40 mg/d group was 5.00%±2.32% and the rate of the patients with low on-treatment platelet aggregation was 71.00%. The rates of melena or occult blood positive, other minimal bleeding,upper gastrointestinal symptoms and a history of gastrointestinal bleeding in 40 mg/d group were higher than those in 100 mg/d group. On a regimen of aspirin 40 mg/d, AA-Ag increased to 11.21%±4.95%(range: 2.12% to 28.84%) with 95.00%of the patients with AA-Ag<20%and the rate of the patients with low on-treatment platelet aggregation was 15.00%. Multiple variable analysis revealed that aspirin 40 mg/d AA-Ag was significantly influenced by aspirin 100 mg/d AA-Ag, BMI and platelet counts. The rate of gastrointestinal bleeding decreased from 12.00% to 5.00%,and upper gastrointestinal symptoms decreased from 59.00% to 21.00% after the switch in 40 mg/d group. Conclusion: Switching aspirin dosage from 100 mg/d to 40 mg/d reduces the bleeding events and improves upper gastrointestinal symptoms, thus inhibiting platelet aggregation effectively in very elderly patients.

Aspirin; Platelet aggregation; Aged, 80 and over; Hemorrhage; Dosing

国家国际科技合作专项(2013DFA30860)资助Supported by China International Science and Technology Cooperation Program (2013DFA30860)

时间:2016-9-5 9:41:31

http://www.cnki.net/kcms/detail/11.4691.R.20160905.0941.024.html

R973.2

A

1671-167X(2016)05-0835-06

10.3969/j.issn.1671-167X.2016.05.016

△ Corresponding author’s e-mail, meilinliu@yahoo.com